Sketches of Spain – Barcelona in Detroit: Four Special Collaborative Cuvées from Two Emerging Regions (10-Bottle Pack $289, Tax Included)

If you’ve enjoyed a Spanish wine from our shop it more than likely came from a local, Detroit-based enterprise that has collected a portfolio of distinguished, passionate producers from some of the most exciting wine production regions in Spain. Vinovi & Co. is led by Núria Garrote i Esteve.

Born and raised in Barcelona, importer Núria Garrote i Esteve has extended her cultural fluency across many continents and in multiple languages. She first moved to Detroit in 2005 to work in automotive industry, where, armed with a degree in Mechanical Engineering from the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, she forged a career with some of the biggest suppliers in the city.

You can take an engineer out of Catalunya, but you can’t take the mystical lure of the region out of the engineer: With an abiding love for her native land and an undying respect for the ‘maestros’ that create the signature wines of Catalunya, Núria launched her import company in order to bring the best of them to her new home in Michigan. Her self-described mission has been to represent an elite group of trailblazing Franco-Iberian winemakers, and her portfolio has been painstakingly assembled after numerous visits to wineries, through walking the vineyards and learning the nuances of the land, the fruit, and above all, the winemakers. “There are as many points of view articulated through wine and cultivation techniques as there are good wines. My producers are as different from each other as their farms.”

Although Núria is steadfast in her vow never to tailor a wine to suit the peculiarities of a market, the barrel-select wines in this package so impressed her that the winemakers graciously allowed her to import them under the name of daughter Ona. Then only 5, the original labels were written in Ona’s own hand.

Priorat

Wine people tend to like lists, so here’s a short one: Appellations that produce superlative wines based on Grenache (Garnacha in Spanish; Garnatxa in Catalan). There’s Châteauneuf-du-Pape, and in Navarra there’s Domaines Lupier… and there is Priorat.

An even shorter list is those Spanish regions that have earned Spain’s top wine designation, Denominación de Origen Calificada DOCa, Denominació d’Origen Qualificada DOQ in Catalan. That honor includes just two appellations, Rioja… and Priorat.

An even shorter list is those Spanish regions that have earned Spain’s top wine designation, Denominación de Origen Calificada DOCa, Denominació d’Origen Qualificada DOQ in Catalan. That honor includes just two appellations, Rioja… and Priorat.

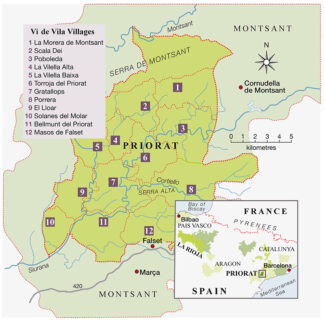

And now for a much, much longer list: The reasons why Priorat’s dry, dusty wine-growing region is so remarkable. Covering 11 parishes located inland from the city of Tarragona in northern Spain, Priorat is engulfed nearly entirely by the Montsant DO (Denominación de Origen), but enjoys specific geological and climactic conditions similar to Andalucía on Spain’s opposite corner. The difference is the soil; in Priorat, it is slate and quartz in the process of breaking down into constituent minerals, and these show up in the wines, giving it a pronounced and identifiable minerality. Priorat’s soil is known locally as ‘llicorella’; it is shiny-black and fine-grained in appearance and is notoriously poor for most agricultural endeavors as it does not retain water and offers little in terms of plant nutrition. But as we learned in Viticulture 101, this sort of earthen foundation is ideal for producing wonderful wines since the vines struggle and fuss and yield grapes reluctantly, and these tend to be small and the juice highly concentrated. Farmers further reduce yields by various techniques in the field and appellation regulations are particularly stringent in Priorat; the Spanish average for grape yields is around two ton per acre—in Priorat, it is one-fifth of that.

And now for a much, much longer list: The reasons why Priorat’s dry, dusty wine-growing region is so remarkable. Covering 11 parishes located inland from the city of Tarragona in northern Spain, Priorat is engulfed nearly entirely by the Montsant DO (Denominación de Origen), but enjoys specific geological and climactic conditions similar to Andalucía on Spain’s opposite corner. The difference is the soil; in Priorat, it is slate and quartz in the process of breaking down into constituent minerals, and these show up in the wines, giving it a pronounced and identifiable minerality. Priorat’s soil is known locally as ‘llicorella’; it is shiny-black and fine-grained in appearance and is notoriously poor for most agricultural endeavors as it does not retain water and offers little in terms of plant nutrition. But as we learned in Viticulture 101, this sort of earthen foundation is ideal for producing wonderful wines since the vines struggle and fuss and yield grapes reluctantly, and these tend to be small and the juice highly concentrated. Farmers further reduce yields by various techniques in the field and appellation regulations are particularly stringent in Priorat; the Spanish average for grape yields is around two ton per acre—in Priorat, it is one-fifth of that.

This package, with ten bottles ($289, all inclusive), contains two bottles of each of Priorat and three bottles of each of Penedès wines.

CLOS PETITONA (Priorat – Masos de Falset)

Priorat – Vi de Vila Masos de Falset Red 2016 ($72)

Priorat – Vi de Vila Masos de Falset Red 2016 ($72)

‘Petitona’ means ‘Little Ona’—indeed domain size of the wine’s namesake Ona, only seven years old in 2016, is 3.5 acres planted to 3,200 vines. Located in the DO Montsant village of Falset (where both DO Montsant or DOCa Priorat wine can be produced depending on the soils of the vineyards), winemaker Blai Ferré’s style has evolved to reflect the terroir’s dazzling complexity. ‘Vi de Vila’ (the wine of a specific municipality) was formally approved by the Spanish Regulatory Council in 2009 and is meant to be the official confirmation of what wine lovers have always known: That the expression of wine varies from town to town.

Petitona is equal parts traditional Catalan Garnatxa and a variety known as Garnatxa Peluda—‘Hairy’ Garnatxa—because the vine leaves are covered in fine hairs that make it drought resistant. Perfumed rather than floral, the wine shows an earthen nose with baking spice and especially, a touch of licorice-ash from which the soil llicorella gets its name.

ONA (Priorat)

Priorat Red 2017 ($19) The first collaborative effort between Núria Garrote and Blai Ferré was in 2013; Blai himself fell in love with winemaking while a teenager working the fields with Alvaro Palacios, one of the leading winemakers not only in Priorat, but all the world. He then purchased two small lots of his own, about 12 acres worth of land from which he produces a scant 5,000 bottles of Ona per year, bottling the rest of the harvest in two other cuvées; the 2017 is a blend of Garnatxa, Syrah, Carinyena and a splash of Cabernet Sauvignon.

Priorat Red 2017 ($19) The first collaborative effort between Núria Garrote and Blai Ferré was in 2013; Blai himself fell in love with winemaking while a teenager working the fields with Alvaro Palacios, one of the leading winemakers not only in Priorat, but all the world. He then purchased two small lots of his own, about 12 acres worth of land from which he produces a scant 5,000 bottles of Ona per year, bottling the rest of the harvest in two other cuvées; the 2017 is a blend of Garnatxa, Syrah, Carinyena and a splash of Cabernet Sauvignon.

Cultivation is organic and the harvest is hand-picked and hand-sorted. Half of the wine is aged in stainless steel vats and the other half in French oak for eight months. Blai likes being self-sufficient and doing everything himself and most of his time is spent working with his father-in-law at Celler Cecilio, the oldest winery in Priorat.

Ona is Priorat in the raw, with little elaboration, merely the core of great fruit showing the potential for creating the type of wine Priorat has become known for: Upscale wines intended for the cellar that reveal an insight into time and place after years of development.

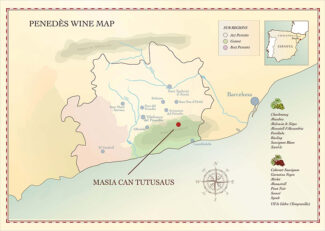

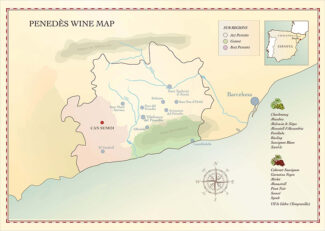

Penedès

About an hour south of Barcelona, nestled splendidly between the mountains and the sea, Penedès is most active growing region in Catalunya. The region contains some of the oldest wine-growing appellations in Europe, and produces consistently and reliably thanks to a multitude of terroirs. The region is best known for Cava, Spain’s answer to Méthode Champenoise sparkling wine, generally produced from the trinity of indigenous grapes, Macabeu, Parellada and Xarel·lo, occasionally fattened-up with Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Garnatxa and Monastrell. All are permitted in various concentrations for Cava blends.

Roughly divided into three subzones, the mountainous Alt-Penedès produces the highest quality wine, followed by Baix Penedès in the low-lying coastal areas and Penedès Central, responsible for most of the region’s bulk production.

Roughly divided into three subzones, the mountainous Alt-Penedès produces the highest quality wine, followed by Baix Penedès in the low-lying coastal areas and Penedès Central, responsible for most of the region’s bulk production.

Although the area has been making wine since the days of the Phoenicians, Penedès’ modern era began in 1960 when its DO designation was granted, and—largely through the efforts of Miguel Torres—the region as a whole began to upgrade production methods, including temperature-controlled fermentation in stainless steel tanks and experimentation with non-indigenous grape varieties such as Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. Since then, although quality has skyrocketed among all the wines of Penedès, the region remains known primarily for its sparkling wines, making the highly regarded, oak-aged reds and crisp, vibrant whites (especially those made with the Cava standby Xarel·lo) part of a remarkable journey of discovery.

ONA (Penedès)

Penedès Red 2015 ($15) Another winemaker whose visionary approach impressed Núria Garrote is Raimon Badell of Masia Can Tutusaus, whose award-winning Cava she imports. During one trip, she tasted a unique red wine produced only for Raimon and his friends; the grape used was called Marselan, a variety created in 1961 by crossbreeding Cabernet Sauvignon with Grenache. Originally, it was intended for use in Languedoc, but yields proved too low for commercial viability.

Penedès Red 2015 ($15) Another winemaker whose visionary approach impressed Núria Garrote is Raimon Badell of Masia Can Tutusaus, whose award-winning Cava she imports. During one trip, she tasted a unique red wine produced only for Raimon and his friends; the grape used was called Marselan, a variety created in 1961 by crossbreeding Cabernet Sauvignon with Grenache. Originally, it was intended for use in Languedoc, but yields proved too low for commercial viability.

Even so, Núria recognized that wine displayed the exuberant red fruit of Grenache and the elegant structure of Cabernet Sauvignon, and saw it as a fitting addition to her custom Ona line. Raimon believes in making contemporary wines that respect Mediterranean culture without becoming mired in convention. Certified biodynamic in Spain, he has the utmost respect for his vines and soil and it shows in every glass.

ONA (Penedès)

Penedès 2019 White ($15) Over the past 20 years, producers have been experimenting with various incarnations of the indigenous grape Xarel·lo; the mountainous sub-zone of the Massís del Garraf possesses a terroir and microclimate perfectly suited to it and beyond its Cava face, it produces a vibrant still wine with signature aromas of green apples, dried flowers and crisp citrus rind.

Penedès 2019 White ($15) Over the past 20 years, producers have been experimenting with various incarnations of the indigenous grape Xarel·lo; the mountainous sub-zone of the Massís del Garraf possesses a terroir and microclimate perfectly suited to it and beyond its Cava face, it produces a vibrant still wine with signature aromas of green apples, dried flowers and crisp citrus rind.

Naturally high in acidity when grown at high Penedès altitudes, freshness of the varietal is neither elaborated upon nor hindered in its expression by Raimon Badell. To Badell, less is often more, and the wine is a beautiful introduction into the intense aromatics, yellow fleshy fruit and exuberance that the variety has to offer.

- - -

Posted on 2021.09.28 in France, Spain DO, Penedes, Priorat DOQ, Wine-Aid Packages, Catalunya | Read more...

‘The Lord of Beaujolais’: Moulin-à-Vent Boasting Structure and Elegance in Three Top Producers’ Wines (6-Bottle Pack $238, Tax Included)

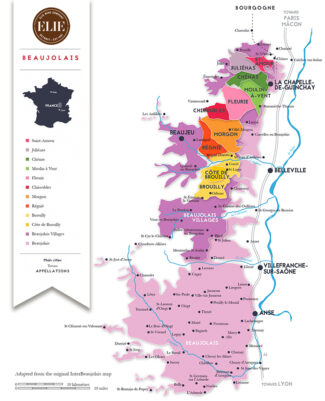

Moulin-à-Vent is to the ten crus of Beaujolais what Moulin Rouge is to Parisian cabarets: First among equals. Of course, that equality is a matter of taste—some consumers prefer floral Fleurie or charming Chiroubles to the full-bodied, tannic-structured Moulin-à-Vent and it’s no secret Georges Dubœuf sells a hundred thousand cases of Beaujolais Nouveau a year.

Forgetting the forgettable and concentrating on the myriad styles of Cru Beaujolais, nowhere is the evidence of terroir—the site-specific contributions of geology, sun-exposure and rainfall—more obvious than in Moulin-à-Vent. Although each appellation works with a single grape variety, Gamay, the results range from light, glorified rosé to densely layered, richly concentrate reds that rival Burgundian Pinot Noir cousins from the most storied estates. Moulin-à-Vent is unusual for a number of reasons, and among them is the fact that there is no commune or village from which it takes its name. Like the Moulin Rouge, the appellation is named for the ‘moulin’—windmill—that sits atop the hill that overlooks the south- and southeast-facing vineyards.

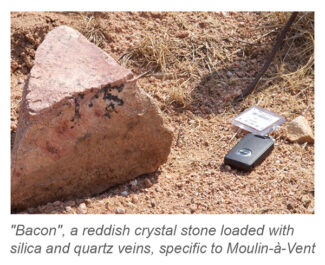

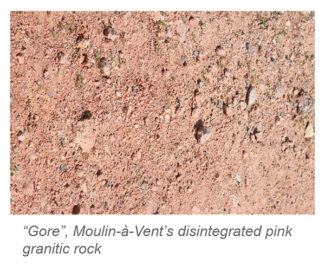

The most outrageous reality of the Cru, however, is that the wine owes its structure and quality to poison: Manganese, which runs in veins throughout the pink granite subsoil, is toxic to grapevines when present in soil at excessive levels and results in sickly vines that struggle to leaf out and produce small clusters of tiny grapes. It is the concentration of the juice in these grapes that gives Moulin-à-Vent a characteristic intensity unknown in the other crus of Beaujolais, where Manganese is not present. It also gives the wine the foundation of phenolic compounds required for age-worthiness; Moulin-à-Vent is among a very select few of Beaujolais wines that can improve for ten, and even twenty years in the bottle ending up with a magnificent cherry-red color – a color that demonstrates the ability of this cru to “pinoter” with age. That French term simply means that they slowly develop a bouquet similar to Pinot Noir, known for its intense ripe fruit notes.

The most outrageous reality of the Cru, however, is that the wine owes its structure and quality to poison: Manganese, which runs in veins throughout the pink granite subsoil, is toxic to grapevines when present in soil at excessive levels and results in sickly vines that struggle to leaf out and produce small clusters of tiny grapes. It is the concentration of the juice in these grapes that gives Moulin-à-Vent a characteristic intensity unknown in the other crus of Beaujolais, where Manganese is not present. It also gives the wine the foundation of phenolic compounds required for age-worthiness; Moulin-à-Vent is among a very select few of Beaujolais wines that can improve for ten, and even twenty years in the bottle ending up with a magnificent cherry-red color – a color that demonstrates the ability of this cru to “pinoter” with age. That French term simply means that they slowly develop a bouquet similar to Pinot Noir, known for its intense ripe fruit notes.

2018 Vintage: Rich with Breath of Freshness

A cold and rainy winter was followed by a warm, dry summer; the first quarter of 2018 was the most humid experience in Beaujolais since 1964. As a consequence, mildew spread fast, but in May and June, sunny conditions saw the condition evaporate. In Beaujolais a condition known as “La fleur a coulé” developed, meaning that the clusters were long, loose, with some millerandagereported (due to the wet spring) and required extensive sorting after harvest. Overall, it is reported to be a powerful and elegant vintage due to the small, concentrated fruit.

2019 Vintage: ‘Solar’ Vintages Continue

Sharp April frosts cut yields throughout the region. The summer then heated up, with reports of temperature highs exceeding 104°F. Drought further cut into yields, and hailstorms struck in mid-August, concentrating the fruit that remained on the vines. Although a heartbreaking loss to farmers, the resulting wine is very intense with nicely balanced acids and Rhône-like aromas. The top estates produced cellar-worthy gems—a marvelous representation of what the appellation can offer.

This 6-bottle pack contains two bottles of each of the following three featured wines at $238 including tax.

Château du Moulin-à-Vent

Château du Moulin-à-Vent has a history as unique and fascinating as the wine. In the late 1700s, Philiberte Pommier discovered that certain plots on her estate yielded better wines than others, and set out to understand the geology that underscored a self-evident truth. She began to tailor her winemaking to individual lieux-dits in her property (then called Château des Thorins), and in 1862, Pommier’s wines were deemed the best in the Mâcon region at the Universal Exhibition of London. At the time, Philiberte Pommier was 99 years old.

Today, the estate encompasses nearly a hundred acres and covers some of the appellation’s finest climats—Les Vérillats, Le Champ de Cour, La Rochelle—with an average vine age of over forty years. The pink granite soil is rich in iron oxide, copper and manganese, and since 2009, under the new ownership of the Parinet family, investment in the winemaking facilities and the vineyards has resulted in plot-specific signature wines.

Château du Moulin-à-Vent, Moulin-à-Vent 2018 ($40): Three unique terroirs on the estate are blended to create this luscious flagship wine: “Les Thorins” is an iconic south-facing plot, “Le Moulin-à-Vent” looks eastward and “Aux Caves” is rich in silica with 80-year-old vines. The wine is deep red color with purple tints and lovely aromas of wild berries, hints of cardamom and flowers; notably rose, peony and violates with spice reasserting itself on the finish.

Château du Moulin-à-Vent, Moulin-à-Vent 2018 ($40): Three unique terroirs on the estate are blended to create this luscious flagship wine: “Les Thorins” is an iconic south-facing plot, “Le Moulin-à-Vent” looks eastward and “Aux Caves” is rich in silica with 80-year-old vines. The wine is deep red color with purple tints and lovely aromas of wild berries, hints of cardamom and flowers; notably rose, peony and violates with spice reasserting itself on the finish.

Domaine Thibault Liger-Belair

Winemaking has been the legacy of the Liger-Belair family for a quarter of a millennium. Prior to establishing his own domain, Thibault Liger-Belair studied oenology and viticulture for six years, worked for a communications firm in Paris and started an internet company to discover and sell high quality wines. Still, the vines beckoned, and in 2001, at the age of 26, he returned to them. The following year saw his first harvest of Nuits-Saint-Georges, and in 2003, he expanded into Richebourg Grand Cru, Clos Vougeot Grand Cru and Vosne-Romanée Premier Cru Petits Monts. In 2009, he ranged farther afield, into Beaujolais, and now produces Beaujolais-Villages and several Moulin-à-Vent wines.

The soil in his Moulin-à-Vent property is shallow (less than 20 inches deep) and composed primarily of granitic sand and quartz, and about half the vines of the 35 acres were planted between 1910 and 1955. His signature wine, for this reason, is ‘Les Vieilles Vignes’—’The Old Vines’.

Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Les Vieilles Vignes’ Moulin-à-Vent 2018 ($45): A cuvée blending nine old-vine parcels of old vines located in a belt around the Moulin-à-Vent hill. The wine offers exotic aromas of spiced candied cherries with a rustic undertow of damp earth; bright, fresh with a firm tannic structure and long, sweet finish.

Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Les Vieilles Vignes’ Moulin-à-Vent 2018 ($45): A cuvée blending nine old-vine parcels of old vines located in a belt around the Moulin-à-Vent hill. The wine offers exotic aromas of spiced candied cherries with a rustic undertow of damp earth; bright, fresh with a firm tannic structure and long, sweet finish.

Domaine Diochon

Domaine Diochon is so close to the iconic windmill that the leaves of the vines are stirred by the breeze it creates. Nearly as famous as the mill is the heavy, curing Teddy-Roosevelt-mustache of the proprietor, Bernard Diochon, who took over the estate from his father in 1967. In waxing philosophically about his terroir, he references ‘crumbly granite soil that allows the vines to plunge easily towards gore subsoil, which feeds the vines, while adding a pronounced mineral component to the wine.’ For the geologically challenged, ‘gore’ is an accumulated mass of sand and thin clay deposits with weathered feldspars, mica, and quartz.

Creating wine from vines between forty and a hundred years old, Diochon is a fan of the specific qualities of the tannins in wines from Moulin-à-Vent, which are unique to the appellation. “I like tannic wines without heaviness; with fruit and floral aromas. I don’t like weighty wines with hard tannins. My favorite wines are Saint-Émilion from Bordeaux, and Chambolle-Musigny and Nuits-Saint-Georges from Burgundy. Every vigneron naturally chooses to make wines in the style they prefer.”

In this, he is as good as his word, having established the benchmarks of his house style: Harvesting only when the grapes are perfectly mature, using (of course) traditional whole cluster fermentation, aging in large old oak foudres and bottling unfiltered in the springtime.

Domaine Diochon ‘Vieilles Vignes’, Moulin-à-Vent 2019 ($26): Notes by the importer: “Juicily delicious yet there is majesty to it. It is full-blown and full-bodied, yet it has a lush, supple texture. No hard edges. No astringency. No heat. The color, like the flavor, is cassis-like. Diochen’s wild moustache looks as if it has seen the inside of a million wine glasses, and it’s hard to imagine a world without wine like this.”

Domaine Diochon ‘Vieilles Vignes’, Moulin-à-Vent 2019 ($26): Notes by the importer: “Juicily delicious yet there is majesty to it. It is full-blown and full-bodied, yet it has a lush, supple texture. No hard edges. No astringency. No heat. The color, like the flavor, is cassis-like. Diochen’s wild moustache looks as if it has seen the inside of a million wine glasses, and it’s hard to imagine a world without wine like this.”

- - -

Posted on 2021.09.16 in France, Beaujolais, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

What Land Really Smells Like: A Passionate Grower-Maker Captures Catalunya’s Mediterranean Fauna & Flora in Three Colors Natural·ly (10-Bottle Pack $261, Tax Included)

From the unblemished beauty of Mediterranean seascapes to the leafy boulevards of Barcelona—a port that has outgrown its geography—Catalunya is a breeding ground for talent. With each detail hooked to history and every footprint pushing toward the future, Catalan creators like Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí and Pau Casals have produced works of genius as reliably as the bells of the Sagrada Família, Gaudí’s iconic melting-castle cathedral.

Into this rarified atmosphere of pride and passion, amid the luster and brinkmanship of Spain’s central government and the secessionist spirit of Catalunya, Pepe Raventós has embellished the canvas with his own unique set of colors. Born to the vine and enamored of the bosky hills and sprawling vineyards of Catalan wine country, Raventós spent his childhood picking grapes at Sant Sadurní d’Anoia. Sant Sadurní is, of course, the home of more than eighty Cava producers and wine is cornerstone of the local economy. It’s also where 21 generations of Pepe Raventós’ family have lived, dating back to the 15th century.

Referring to the wine region as the ‘New Catalunya’, Raventós—whose love of nature, sustainable agriculture and natural vinification is perhaps unparalleled in the world—searched for several years before he found his dream property between the towns of Sant Jaume dels Domenys and Pla de Manlleu: The thousand acre woodland and farm of Can Sumoi. The vineyard had fallen on hard times, and Josep Mateu, a former masover (farmhand) who was born at Can Sumoi in 1936, was delighted that someone was willing to ‘recover the land’. Under the stewardship of Raventós and his childhood friend Francesc Escala, Mateu maintains that he can, once again, “see the sun shine through open door, watch the vines being pruned and cars going up and down the narrow path between the olive trees.”

Referring to the wine region as the ‘New Catalunya’, Raventós—whose love of nature, sustainable agriculture and natural vinification is perhaps unparalleled in the world—searched for several years before he found his dream property between the towns of Sant Jaume dels Domenys and Pla de Manlleu: The thousand acre woodland and farm of Can Sumoi. The vineyard had fallen on hard times, and Josep Mateu, a former masover (farmhand) who was born at Can Sumoi in 1936, was delighted that someone was willing to ‘recover the land’. Under the stewardship of Raventós and his childhood friend Francesc Escala, Mateu maintains that he can, once again, “see the sun shine through open door, watch the vines being pruned and cars going up and down the narrow path between the olive trees.”

At two thousand feet above sea level (in the Serra de l’Home range) Can Sumoi is the highest estate in the Penedès; Mallorca and the Ebro Delta are visible from the rooftop of the winery’s 350-year-old farmhouse. Below, 50 acres of vineyards sprawl across limestone-rich soil between stands of oak and white pine, which to the ecology-driven Raventós, share equal importance with the vines. “Forests,” he says, “protect the biodiversity of the estate; they are the green lungs of the world.”

The wines of Can Sumoi are also green insofar as they are produced using Certified Organic methods; vineyards are tended with natural compost, free of pesticides and with minimal intervention; a herd of sheep and goats is allowed to graze semi-freely among the vines. Certain esoteric biodynamic techniques may sound strange to laymen (such as timing vineyard activity to the phases of the moon) but to Raventós, they make perfect sense: “When the moon is ascendant, plant fluids concentrate more towards the roots of plants, and that’s when you want to do the pruning—so you don’t damage the plant.”

In 2014, Raventós began experimenting with Natural wines, unfiltered and without added sulfites— ‘Wine Spectator’ described his 2016 Xarel-lo Espumoso Ancestral as having ‘aromas of freshly baked apple pie and lemon rind and a tasty, almost salty palate, as if the process amplifies the marine character and especially the flavors, with a combination of faintly bitter and slightly volatile characters’. Raventós says, “I observe the countryside and see how it responds. If we apply earth-friendly techniques, I see that the earth is more alive, more balanced and we are getting better wines, so of course, I continue to apply them.”

In keeping with a desire to express aromas and flavors exclusive to Catalan in a natural winemaking style, Can Sumoi is planted only to indigenous varieties, Parellada, Xarel-lo and Sumoll. The first two are white, and are among the trio used in Cava. Sumoll, which occupies about five acres of the vineyard, is a wild and rustic red grape tamed by the estate’s high altitude; it produces mineral-driven wines with a distinctive cherry flavor. Each of Can Sumoi’s varieties expresses olfactory nuances unknown in any other wine region, often reflecting the flora of northeast Spain, and it is Raventós’ mission to produce high-altitude wines that define the balance, harmony and austerity of Catalunya; when you drink them—or any wine, for that matter, says Raventós—your mind and spirit should travel to the place of origin. “I try to create an essence of place, or at least, to interpret its authenticity. When you’re drinking a beautiful Nebbiolo, for example, you go to the slopes of Serralunga D’Alba or La Morra and even see the landscape. I try to do the same thing with the breathtaking sights and savory tastes of Catalunya.”

It is a spiritual quest, he admits; the smells and flavors of Catalunya are unique and exist in his soul as surely as in his wine. “To express origin, you really need to bring a lot of life into your farm. The principle is simple: The more diversity on your property, the more richness there is, the more resistant and strong your vines will be. The fewer treatments they need, the more authentic the wine will be. I left the idea of making perfect wine a long time ago. I think my duty is to make the most authentic wine possible.”

Can Sumoi 10-Bottle Pack $261 (tax included) contains two of each of the following four wines:

‘Ancestral Sumoll’ Espumoso (Sparkling) Brut Nature 2018 Rosé ($28): The name ‘Sumoll’ has roots in the Latin word ‘submolliare’ which means ‘to wither’, perhaps in reference to Sumoll’s use in producing high-end straw wines. Here, this 100% Sumoll occupies the opposite end of the wine spectrum as straw wine; it is a bone-dry, gently floral sparkler with fresh black fruit aromas accented by saltiness and toasted almond notes. Don’t expect a Champagne-ferocious fizz; rather than using Méthode Champenoise, ‘Ancestral Sumoll’ is partially fermented in stainless steel vats with fermentation completed inside the bottle, resulting in gentler effervescence.

‘Ancestral Sumoll’ Espumoso (Sparkling) Brut Nature 2018 Rosé ($28): The name ‘Sumoll’ has roots in the Latin word ‘submolliare’ which means ‘to wither’, perhaps in reference to Sumoll’s use in producing high-end straw wines. Here, this 100% Sumoll occupies the opposite end of the wine spectrum as straw wine; it is a bone-dry, gently floral sparkler with fresh black fruit aromas accented by saltiness and toasted almond notes. Don’t expect a Champagne-ferocious fizz; rather than using Méthode Champenoise, ‘Ancestral Sumoll’ is partially fermented in stainless steel vats with fermentation completed inside the bottle, resulting in gentler effervescence.

• Alcoholic Content: 10.6 %

• Total Tartaric Acidity: 5.7 g/l

• pH: 3.21

• Volatile Acidity: 0.53 g/l

• Residual Sugar: 0.3 g/l

• No added SO2. Total SO2: <4 mg/l

• Pressure: 5 atm

‘Xarel-lo’ Penedès 2019 White ($24): In the Catalan language, the variety’s name is written with an interpunct dot (Xarel·lo) but in English, the dot becomes a hyphen. Either way, this wine delivers a clean, fresh and electric sizzle, echoing the wild landscape that produced it with aromas of fennel and thyme along with green, acidic apples and a hint of salinity.

• Alcoholic Content: 12.1 %

• Total Tartaric acidity: 5.7g/l

• pH: 3.25

• Volatile Acidity: 0.33g/l

• Residual Sugar: >0.5g/l

• Total SO2: 25 mg/l

‘Perfum’ Penedès 2020 White ($22): 30% Malvasia, 30% Macabeo, 25% Moscatell, 15% Parellada; the wine is an elegant triumph of aromatics, and hence, the name. Spring flowers, white peaches and freshly pressed grapes over a background of wild herbs and Can Sumoi’s signature saltiness well-balance by honey.

‘Perfum’ Penedès 2020 White ($22): 30% Malvasia, 30% Macabeo, 25% Moscatell, 15% Parellada; the wine is an elegant triumph of aromatics, and hence, the name. Spring flowers, white peaches and freshly pressed grapes over a background of wild herbs and Can Sumoi’s signature saltiness well-balance by honey.

• Alcoholic Content: 11.0 %

• Total Tartaric Acidity: 5.7g/l

• pH: 3.21

• Volatile Acidity: 0.29g/l

• Residual Sugar: <0.5g/l

• Total SO2: 30mg/l

‘La Rosa’ Penedès 2020 Rosé ($24): 50% Sumoll, 30% Parellada, 20% Xarel-lo; a shimmery, orange-pink wine offering vibrant ripe cherry flavors and spicy tangerine with a touch of anise in the mid-palate, finishing with a sharp, chalky minerality.

‘La Rosa’ Penedès 2020 Rosé ($24): 50% Sumoll, 30% Parellada, 20% Xarel-lo; a shimmery, orange-pink wine offering vibrant ripe cherry flavors and spicy tangerine with a touch of anise in the mid-palate, finishing with a sharp, chalky minerality.

• Alcoholic Content: 11.1 %

• Total Tartaric Acidity: 5.3g/l

• pH: 3.22

• Volatile Acidity: 0.37g/l

• Residual Sugar: >0.50g/l

• Total SO2: 32mg/l

‘Sumoll Garnatxa’ Penedès 2019 Red ($25): 50% Garnatxa Negre, 50% Sumoll; Can Sumoi’s clay limestone soils is ideal for Garnatxa (called Garnacha elsewhere in Spain and Grenache in France) and the elevation reigns in some of Sumoll’s feral foxiness, leaving a sweet boysenberry, cinnamon and pomegranate flavored, crimson-colored blockbuster, combining rusticity with an essential elegance that is, like salinity, a Can Sumoi trademark.

‘Sumoll Garnatxa’ Penedès 2019 Red ($25): 50% Garnatxa Negre, 50% Sumoll; Can Sumoi’s clay limestone soils is ideal for Garnatxa (called Garnacha elsewhere in Spain and Grenache in France) and the elevation reigns in some of Sumoll’s feral foxiness, leaving a sweet boysenberry, cinnamon and pomegranate flavored, crimson-colored blockbuster, combining rusticity with an essential elegance that is, like salinity, a Can Sumoi trademark.

• Alcoholic Content: 13%

• Total Tartaric Acidity: 6.12 g/l

• pH: 3.31

• Volatile Acidity: 0.42 g/l

• Residual Sugar: >0.5 g/l

• No added SO2. Total SO2: 24 mg/l

- - -

Posted on 2021.09.10 in France, Spain DO, Penedes, Wine-Aid Packages, Catalunya | Read more...

Power with Restraint: Seven Top Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé Estates Deliver a Top Vintage in 2018’s Miracle Harvest (7-Bottle Pack $385, Tax Included)

In Bordeaux, Cabernet Sauvignon is the duke of the manor while Merlot is the duchess, and if these terms sound antiquated in 2021, be assured that the traditions of the region are delightfully established. And nowhere in Bordeaux is this genuflection to history more obvious than in Saint-Émilion, which is speckled with Roman ruins and at whose center stands a limestone church built by the region’s namesake, Saint Emilian of Lagny.

In Bordeaux, Cabernet Sauvignon is the duke of the manor while Merlot is the duchess, and if these terms sound antiquated in 2021, be assured that the traditions of the region are delightfully established. And nowhere in Bordeaux is this genuflection to history more obvious than in Saint-Émilion, which is speckled with Roman ruins and at whose center stands a limestone church built by the region’s namesake, Saint Emilian of Lagny.

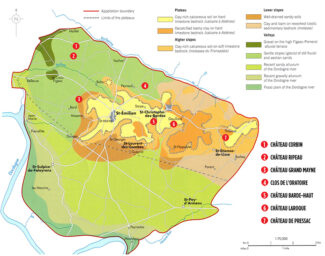

Saint-Émilion was the first region in Bordeaux to export wines and boasts the oldest wine society in France: The Jurade of St Émilion, formed in 1199. The vineyards are numerous and small, averaging around fifteen acres and spread across a triad of terroirs that can be roughly defined as a central limestone plateau, the clay and chalk-rich slopes of that plateau and the flatland beyond. What all three topographical areas have in common is cooler soils better suited to Merlot and Cabernet Franc. For the most part, Cabernet Sauvignon does not ripen well in Saint-Émilion except in small pockets, most notably on an ancient alluvial terrace in the northwest, where free-draining gravel soils are similar to those found in the best properties of the Graves and Médoc.

An official classification of Saint-Émilion châteaux was first conducted in 1955, updated in 1996, 2006 and again in late 2012. As a result, the best wines of the region can be found in two principal tiers: Grand Cru Classé and Premier Grand Cru Classé. Grand Cru Classé marks a significant quality upgrade from standard Saint-Émilion Grand Cru wines, which number in the hundreds. The Saint-Émilion wine classification is the only one to challenge itself every ten years and is held to be the most modern and progressive wine classification that exists. This ten-year renewal is a real advantage, because it inspires all the Saint-Émilion appellation winegrowers to sustain their quest to make unique wines.

SAINT-ÉMILION 2018: EXCELLENCE FORGED OUT OF CLIMATIC EXCESS

2018 represents a vintage in which Saint-Émilion producers snatched victory from the jaws of defeat; ‘Forbes’ wine writer Tom Mullins refers to it as a ‘dark star vintage’, meaning that it is powerful with profoundly deep black fruit flavors integrating beautifully with acidity.

An unusually wet spring produced more rain than the appellation usually receives all year, leaving the vines susceptible to mildew and a prevailing fear that the harvest might be doomed. But a sunny June and a balmy July dried things out as the summer developed into the hottest since 2003 with no substantial rainfall until after harvest. Vignerons were able to pick at their chosen level of maturity and optimal phenolic ripeness was achieved throughout the appellation.

1- Château Corbin

Politically correct connoisseurs may roll their eyes when Merlot is referred to as ‘feminine’, but the line of succession at Château Corbin is unabashedly woman; it has been passed from mother to daughter for multiple generations. Anabelle Cruse-Bardinet is the current owner, and produces silken, sensuous and supple wines from older vines that are, for the record, 92% Merlot. The Cabernet Franc that makes up the rest is often fermented in large glass amphora, and the 18 stainless steel tanks ranging in size from 40 to 80 hectoliters allow for parcel by parcel vinification. The terroir is neatly split between clay-heavy soil peppered with iron deposits and sand and gravel.

2018 Château Corbin, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($55) is 90% Merlot and 10% Cabernet Franc with a perfumed nose of black raspberries, blackberries, toasted spice, dried flowers, and loamy earth with some classic Saint-Émilion chalky minerality, quality tannins, and a long finish.

2018 Château Corbin, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($55) is 90% Merlot and 10% Cabernet Franc with a perfumed nose of black raspberries, blackberries, toasted spice, dried flowers, and loamy earth with some classic Saint-Émilion chalky minerality, quality tannins, and a long finish.

2- Château Ripeau

It’s said that good fences make good neighbors, but if they share good terroir, the rest is immaterial. As such, Château Ripeau’s 40 acres, bordering Pomerol, share breathing air with Château Cheval Blanc, Château Corbin and Château La Dominique, yielding grapes from a similar aggregate of sand, gravel, limestone and iron-infused clay. In December, 2014, Jean and Françoise de Wilde sold Château Ripeau to Cyrille and Nicolas Grégoire, sons of James Grégoire, best known as the previous owner of Fronsac’s Château La Rivière. The brothers have hauled the estate into the 21st century, upgrading the facility, switching to organic farming and replanting 40,000 feet of vines to better densities with improved drainage and more diligent pruning, making them among our favorite folks in the neighborhood.

2018 Château Ripeau, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($50) is deep and brooding with aromas of plum, black cherry, and dark earth wending a path through a complex and layered palate. Graphite, toast, and cherries intermingle with minerals and elegant, soft tannins; the opulent fruit is seamlessly integrated and with enough backbone to carry it through the next decade and beyond.

2018 Château Ripeau, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($50) is deep and brooding with aromas of plum, black cherry, and dark earth wending a path through a complex and layered palate. Graphite, toast, and cherries intermingle with minerals and elegant, soft tannins; the opulent fruit is seamlessly integrated and with enough backbone to carry it through the next decade and beyond.

3- Château Grand Mayne

The Saint-Émilion estate of Grand Mayne is driving a Cabernet Franc steamroller; the 40 acres are currently planted to 78% Merlot, 19% Cabernet Franc and 3% Cabernet Sauvignon, but the plan of the Nony family (who has presided over Grand Mayne since 1934) is to add Cab Franc vines until they make up 35% of the total. This vineyard is located in a single block to the west of the village of St. Émilion, at the foot of the plateau. The vines that creep up the slope (bordering Château Beau-Séjour Bécot) are planted in clay/limestone soil, and in the portion that extends across the flats grow into a layer of sand that offers better drainage—a plus when the season begins with a damp overture, as it did in 2018.

2018 Château Grand Mayne, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($59) is rich, lush, round and packed with sweet, ripe, fresh, opulent black cherries and chocolate. The wine has good concentration, a nose of smoke, licorice, dark red pit fruits and a finish stocked with dusty chocolate-covered plums.

2018 Château Grand Mayne, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($59) is rich, lush, round and packed with sweet, ripe, fresh, opulent black cherries and chocolate. The wine has good concentration, a nose of smoke, licorice, dark red pit fruits and a finish stocked with dusty chocolate-covered plums.

4- Clos de l’Oratoire

‘Fronsac Molasse’ sounds more sophisticated than ‘sand over clay’, but either way, it’s perfect ground to nurture Merlot vines, and as such, 80% of l’Oratoire vines are of that variety. Once a part of neighboring Château Peyreau, l’Oratoire is relatively new kid on the block, especially compared to Saint-Émilion estates with roots delving through centuries. Peyreau split in two around the time of the Saint-Émilion classification (1955), and both properties were purchased by Joseph-Hubert Graf von Neipperg, the father of the current owner, Stephan von Neipperg. At around thirty acres, the estate is farmed with stainable viticulture methods, without herbicides or pesticides.

2018 Clos de l’Oratoire, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($61): The wine blends 85% Merlot and 15% Cabernet Franc; at the core you’ll find licorice, smoke, truffles, cherry, flowers, wet earth, soft tannins and a dried, red pit fruit finish.

2018 Clos de l’Oratoire, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($61): The wine blends 85% Merlot and 15% Cabernet Franc; at the core you’ll find licorice, smoke, truffles, cherry, flowers, wet earth, soft tannins and a dried, red pit fruit finish.

5- Château Barde-Haut

Shored up by more than 250 years of history, Sylviane Garcin-Cathiard (who purchased Barde-Haut in 2000) felt confident in steering the estate toward the next quarter millennia. That involved a modern, minimalist remake of the winemaking facility by Paris architect Nadau Lavergne along with a ‘green roof’ with solar panels, filters to collect and recycle rainwater and a small wind turbine to create outdoor lighting. Meanwhile, the terroir continues to produce—the best sits atop the plateau where clay is layered above chalk soils and limestone.

2018 Château Barde-Haut, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($53) boasting 80% Merlot and 20% Cabernet Franc, the wine is beautifully balanced with a wonderful sense of purity and elegance; ripe black cherry and blueberry fruits alongside medium to full-bodied aromas and flavors of chocolate, spring flowers, violets and a kiss of chalky minerality.

2018 Château Barde-Haut, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($53) boasting 80% Merlot and 20% Cabernet Franc, the wine is beautifully balanced with a wonderful sense of purity and elegance; ripe black cherry and blueberry fruits alongside medium to full-bodied aromas and flavors of chocolate, spring flowers, violets and a kiss of chalky minerality.

6- Château Laroque

Laroque is the biggest estate in Saint-Émilion and perhaps the grandest; they refer to themselves as ‘a paradise of limestone’. Laroque’s terroir is irreplaceable, but it is the human touch that has carried this iconic château from a bulk producer to ‘Grand Cru Classé’ and the estate is happy to name names: First, Paul Boisard, the 19th century estate manager who brought Laroque wines to the attention of the Bordeaux négociants with a gold medal at the 1900 Paris Universal Exhibition; then Bruno Sainson, who oversaw thirty vintages and lifted Château Laroque to the rank of Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé; and of course, current manger, oenologist David Suire, who (with a team of 19) has been tasked with preserving the Laroque heritage while embracing the challenges the future of the industry holds.

2018 Château Laroque, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($42): 97% Merlot and 3% Cabernet Franc; it bursts from the glass with flamboyant notes of stewed black plums, Black Forest cake and boysenberries, plus hints of candied violets, star anise and unsmoked cigars with a playful waft of sassafras.

2018 Château Laroque, Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($42): 97% Merlot and 3% Cabernet Franc; it bursts from the glass with flamboyant notes of stewed black plums, Black Forest cake and boysenberries, plus hints of candied violets, star anise and unsmoked cigars with a playful waft of sassafras.

7- Château de Pressac

The medieval fortress of Pressac has been making wine since 1737, and back in the day, was so committed to the Auxerrois grape that it was renamed ‘Noir de Pressac.’ It is still grown on the estate’s hundred acres, but today it goes by the name of Malbec. (It’s also known as ‘Côt’ in Cahors, where it is the dominant variety). Pressac is unique in Saint-Émilion in that it reserves vineyard space for all six of Bordeaux’s allowable varieties, with 69% on the vineyard devoted to Merlot, 18% to Cabernet Franc, 9% to Cabernet Sauvignon, 2.5% to Malbec, 1.5% to Carménère and 1% to Petit Verdot. The confluence of all three of the appellations soil types makes this possible; the limestone plateau on which the château sits yields to a clay-limestone slope surrounding the hill and at the foot of the slope, silty clay-limestone, each occupying equal parts of the estate.

2018 Château de Pressac Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($42): Ripe blackberry and warm plums are followed by notes of cedar, graphite, herbs de Provence, soft leather and a hint of mint.

2018 Château de Pressac Saint-Émilion Grand Cru Classé ($42): Ripe blackberry and warm plums are followed by notes of cedar, graphite, herbs de Provence, soft leather and a hint of mint.

- - -

Posted on 2021.08.26 in France, Bordeaux, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

A Dozen Rosés: The French Climate Divide: Northern (Oceanic) vs. Southern (Mediterranean) in Six Types by Six Producers (12-Bottle Pack $246, Tax Included)

With apologies to Mr. Shakespeare, a rosé by any other name would probably be sweeter. The fortunes of pink wine have risen and fallen with consumer tastes, especially in the United States, where rosé has endured a shunning for being a backyard party drink to its recent status as a social media star. But in Europe, rosé has been a mainstay for centuries, and in France—which pumps out millions of gallons each year—there was pink before there was red, since the Greeks did not macerate their grapes and that is the technique by which darker wines obtain their color.

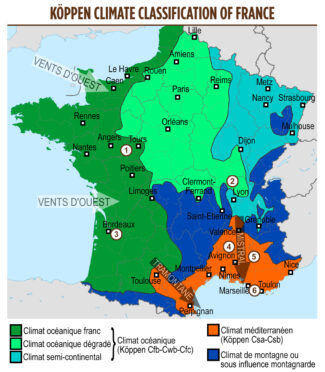

In Provence, where 91% of all wine produced is pink, rosé is (unofficially) classified by shade, lightest to darkest: Peach, Melon, Mango, Pomelo, Mandarin and Redcurrant. These gradations can apply to any blush from any appellation; they are based on the vigneron’s production methods and the grape variety used. But they are also a verbal ode to the lovely fruitiness prized even in the driest rosé, whether made in France’s cooler, damper North, or the warm and windy South.

This package, with dozen bottles ($246, all inclusive), contains selections from six of France’s most highly regarded rosé-producing regions. It represents the spectrum of hues and flavors that mark the climatic influence, as well as the common essence of the dry French ‘rosé style’ that makes it the quasi-official wine of summer. We can deliver the package to you for free within a reasonable distance.

Oceanic Climate

The Temperate & Cold North-Northwest

1- Chinon (Loire)

The confluence of the Loire and Vienne rivers is a demarcation where the influence of the Atlantic sweeps through the two valleys. Vineyards are generally oriented on east to west slopes with sunny southern exposures, creating a microclimate ideal for Cabernet Franc. As a result, the medieval town of Chinon—and the appellation that takes its name—is known for rich reds and vibrant pink wines made from that variety. Beyond the climate, Chinon boasts unique soil; tuffeau jaune is a fragile sedimentary rock made of sand and highly porous marine fossils, meaning that it absorbs water rapidly and disseminates it slowly, ideal for grape cultivation.

Château de la Bonnelière

Château de la Bonnelière

Respect for tradition and love of family are the twin forces that animate Château de la Bonnelière: In 1976, Pierre Plouzeau bought the old family castle and renovated the property while replanting the largely-vanished vineyards. His son Marc took over in 1999 and has become one of Chinon’s most prolific and talented personalities, responsible for a plethora of marvelous juice—red, white and pink. 43 acres of vines and a 1500-square-meter cellar carved out of the castle’s solid stone foundation provide an environment as beautiful as it is fecund. Château de la Bonnelière ‘M Plouzeau – Rive Gauche’, 2020 Chinon Rosé ($17) is a sensationally complex rosé from Cabernet Franc showing notes of limestone, tart cranberry, red currants, raspberry, pomegranate and pink grapefruit.

2- Beaujolais (Greater Burgundy)

Interest in Beaujolais rosé has skyrocketed of late; so much so that the output has increased by 34% in the past four years alone and now approaches two million bottles annually. Rosé is produced exclusively in the Beaujolais and Beaujolais Villages AOPs, with 450 of the region’s 3000 estates offering the style. Like its red wines, Beaujolais rosé is made entirely from Gamay—the difference is that bunches destined to be blush are often macerated only for a few hours before pressing, and the choice of conducting malolactic fermentation is left to the vintner based on the style and profile he is after in any given vintage.

Chermette Vissoux

Chermette Vissoux

The irony of Beaujolais is that it tends to be a wine best consumed in its youth, while the soils to produce it have required 320 million years to evolve. The Vissoux family falls in between that timeline, having established itself in the village of Saint-Vérand in the 17th century. Today, from 15 acres of vines, Pierre-Marie, Martine and Jean-Etienne craft white, rosé and red Beaujolais from crus such as Brouilly, Fleurie, Moulin-à-Vent, Saint-Amour, as well as Crémant de Bourgogne and hand-crafted fruit liqueurs. Chermette Vissoux ‘Griottes’, 2020 Beaujolais Rosé ($18)owes its elegance to soils that are Saint-Vérand specific, consisting of plagio-granite similar to the blue stones of the Côte de Py in Morgon and may be found as far away as Norway. The wine itself is peach-pink, offering the bouquet of fresh spring flowers with sweet Muscat note with spicy star anise on the finish.

3- Bordeaux

Wine is art and wine is poetry, but wine is also marketing, and the relative scarcity of rosé from Bordeaux—France’s hub for massive and structured red wines—is economics. Dark, big-shouldered Cabernets and Merlots command higher prices and have been relatively easy sales, and for the most part, historically lightweight ‘clairet’ wines were bled from vines still too young to make the powerhouse wines expected of a château. Over the past twenty years, however, in keeping with consumer trends, many Bordeaux producers have rethought their approach to rosé, and have begun to produce a style lighter and fruitier than clairet with an eye to attracting a younger market.

Clarendelle

Clarendelle

‘Act fast’ are odd words to sum up the history of Haut-Brion, where vignerons have patiently worked vineyards for centuries, and whose wines often take decades to mature. But those succinct two words were uttered by American banker Clarence Dillon in 1935 when told via telegram that the Premier Grand Cru Classé estate of Haut-Brion could be purchased, but only if his accountants acted fast. They did. Clarendelle, 2020 Bordeaux Rosé ($21) (whose label reads ‘Inspiré par Haut-Brion’) takes it cues from the clairet-style of Bordeaux’s bygone era, and a blend of Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Cabernet Franc juice briefly macerated, then drawn off to preserve the freshness of newly picked grapes. The wine has the delicate hue of rose petals and presents hints of tangy redcurrants and raspberries alongside rounder notes of ripe grapefruit and lychee in a mineral-driven package.

Mediterranean Climate

The Warm & Windy South

4- Tavel (Southern Rhône)

To say ‘Tavel rosé’ is to repeat yourself since, by law, all wine from Tavel is rosé. Creeping along the right bank of the Rhône River in the Gard, the soils of Tavel are a potpourri of small stones called galets roulés, fine sand and fractured limestone, and the hot, dry climate allows the grapes (predominantly Grenache, Syrah and Clairette) to achieve full phenolic ripeness. As a result, Tavel rosé tends to be richer and more deeply colored than the salmon-pink wines from other regions, with an associated complexity of flavor in the glass.

Château de Manissy

Château de Manissy

The estate (which has belonged to the Congregation of Missionary Fathers of the Holy Family since the 18th century) operates under the motto, ‘Auspice clara Manissy Stella’, or, ‘beneath the protection of the bright star of Manissy.’ Since 2004, it has also operated under the auspices of Florian André, whose winemaking and cellar skills have upheld the Château’s reputation for Tête de Cuvée barrel-aged rosé. Château de Manissy, 2020 Tavel Rosé ($18) is 60% Grenache, 30% Clairette, 10% Syrah from vines that average 45 years old grown in clay, river rock and fine-grained sand. It opens with aromas of white flowers and spring strawberries, filling out in a silky blend of watermelon and pomegranate; it is rich in minerality and intriguingly peppery on the finish.

5- Côtes du Rhône (Southern Rhône)

Among the best value rosés in a category already saturated with bargains are the blush wines of the Côtes du Rhône. The offerings cover the spectrum of colors delineated in the Provençal color chart, pale pink to rich raspberry, with a palate that tends toward the full-bodied and exceptionally fruity. Novices have been known to ask if rosé is simply a blend of red and white grapes, and in the case of Côtes du Rhône rosé, up to 20% of the cuvée may be composed of white varieties. For the red grapes, Grenache is the ringleader, with Cinsault, Mourvèdre and Syrah used as supplements and each adding their unique spin to the final profile. For whites, Grenache blanc, Clairette and to a lesser extent, Marsanne may show up.

Domaine Les Aphillanthes

Domaine Les Aphillanthes

Daniel and Hélène Boulle first took over Domaine Les Aphillanthes in 1987, although Daniel was the fourth generation of his family to work this land; at the time of the purchase, the estate covered about 25 acres. Since then, the Boulles have tripled the size of their vineyards (located near Gigondas), gone organic, and are so committed to quality that they hold yields well below the local allowance and will not produce in vintages that do not live up to their expectations. Domaine Les Aphillanthes ‘Nymphea’, 2020 Côtes du Rhône Rosé ($15) is grown on clay and limestone soil, and bottled without fining. The cuvée is primarily Grenache and Cinsault shored up by smaller quantities of Mourvèdre and Counoise; it is fleshy and dry, showing red currant, orange zest and a nice spicy lift.

6- Bandol (Provence)

One of the key appellations in Provence, Bandol received official AOC status in 1941, but has been recognized as a source of rosé wine for far longer: Dumas’ immortal Count of Monte Cristo sipped a glass of Bandol pink ‘bien frais’—well-chilled. The region encompasses almost 4000 acres, a third of which is dedicated to rosé made from a blend (like the reds) dominated by Mourvèdre, Grenache and Cinsault. Located on a stretch of Mediterranean coastline, the vines enjoy warm (often hot) growing conditions moderated by cool wind from the sea and protected from cold northerly winds by the Montagne Sainte-Victoire and the Massif de la Sainte-Baume ranges.

Domaine La Bastide Blanche

Domaine La Bastide Blanche

When, in 1970, Michel and Louis Bronzo purchased La Bastide Blanche, they had a lofty goal: To produce a Bandol wine that would rival Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Their patience paid off in 1993 when a banner vintage put both their domain and Bandol on the world’s wine map. The estate is noted for the high percentage of Mourvèdre used in cuvées—up to 75% for their reds and rosés—while yields of all varieties are kept very low. Domaine La Bastide Blanche, 2020 Bandol Rosé ($27) is delightful summer gem that includes some Grenache and Cinsault behind the Mourvèdre, and is unbeatable as an accompaniment to the local Provençal cuisine. It presents cinnamon, mulled spice, redcurrants and cassis; the acidity is well integrated against the fruit tannins, with a steely mineral edge on the finish.

- - -

Posted on 2021.08.20 in Chinon, Bordeaux, France, Beaujolais, Wine-Aid Packages, Loire, Provence, Southern Rhone | Read more...

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Aglianico, Albarino, Albarín Tinto, Alicante Bouschet, Aligote, Altesse, Arbanne, Arcos, Auxerrois, Barbarossa, Beaune, Biancu Gentile, Bonarda, bourboulenc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Chenin Blanc, Cinsault, Clairette, Cortese, Corvinone, Cot, Counoise, Dolcetto, Erbamat, Fiano, folle Blanche, Fumin, Gamay, Garganega, Garnacha Tintorera, Godello, Graciano, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, Grolleau, Groppello, Jacquère, Juan Garcia, Lladoner Pelut, Macabeo, Maconnais, Malbec, Malvasia, manseng, Marcelan, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Melon de Bourgogne, Mencía, Merlot, Montepulciano, Montònega, Moscatell, Mourv, Mourvèdre, Muscadelle, Muscat, Natural, Nebbiolo, Nero d'Avola, Niellucciu, Palomino, Parellada, Patrimonio, Pecorino, Pedro Ximénez, Persan, Petit Meslier, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Auxerrois, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Pouilly Fuisse, Pouilly Loche, Riesling, Rousanne, Sagrantino, Sangiovese, Sauvignon, Sciacarellu, Semillon, Serine, Sumoll, Tempranillo, Teroldego, Timorasso, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, trepat, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, Vermentino, Viognier, Viura, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012