A Grape of Memory: Ten Provençal Producers Show How Bandol’s Mourvèdre Evolves into Wines of Haunting Complexity and Depths That Only Time Delivers • Future Classics in a Tuck-Away Pack 6 Bottles – $299 (Vintages 2021-2017)

Conventional wisdom has taught us that wine grapes fare best in places where nothing else will grow; rocky, water-starved soil on precipitous hillsides make vine roots work harder, ramifying and branching off in a search of nutrients and, in consequence, producing small grapes loaded with character.

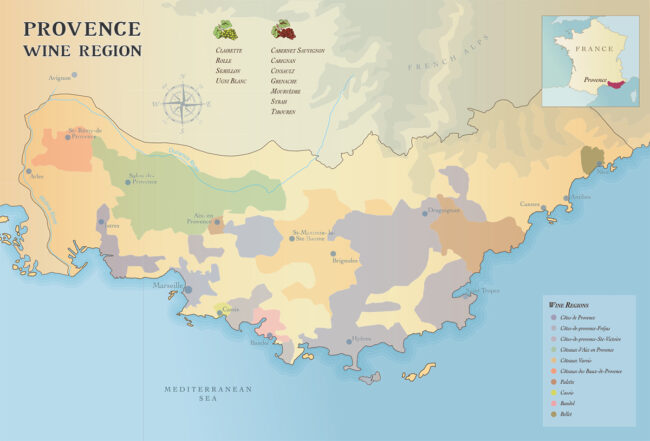

Cue Bandol, the sea-and-sun-kissed region along the French Riviera which is not only good country for grapes, it’s good country for the soul.

Made up of eight wine-loving communes surrounding a cozy fishing village, Bandol breaks the Provençal mold by producing red wines that not only outstrip the region’s legendary rosé, but make up the majority of the appellation’s output. In part that’s due to the ability of Bandol vignerons to push Mourvèdre—generally treated as a blending grape in the Côtes du Rhône and Châteauneuf-du-Pape —to superlative new heights.

Bandol: Where Land Meets the Mediterranean Sea

It may be impossible to find a region where the winemaking pedigree is more impressive; Phoenicians were fermenting grapes here 2500 years ago, long before the Romans showed up and named the wine ‘Massilia.’ As the late-afternoon Bandol heat sends wafts of violet, black pepper and thyme into the air above an azure sea, it’s easy to see why this seacoast resort town has been both a destination and a home since prehistory.

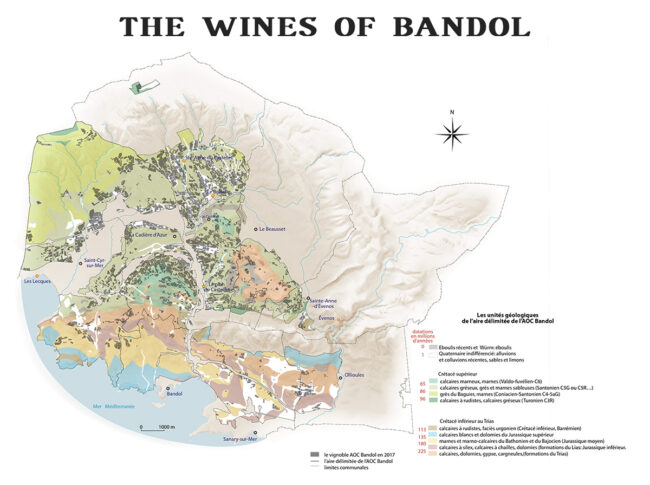

About an hour’s drive east from Marseille, the microclimate that sets Bandol apart from the rest of Provence is the result of altitude and its natural amphitheater; the vines are planted on steep hills where the soils are composed of limestone, red clay and silica sand and the vines are protected from the harshest winds by the natural bowl formed in the low coastal mountain ranges between La Ciotat and Toulon. This combination of features makes it ideal for ripening finicky, late-budding Mourvèdre, which might otherwise be challenged by the proximity of the Mediterranean.

Bandol’s Signature Grape: Mourvèdre, Slow Burn

The ecological niche that makes Bandol’s Mourvèdre unparalleled in the world is the work of both man and nature. While Syrah and Grenache are planted on Bandol’s cooler, north-facing slopes, Mourvèdre is strategically placed on warmer, south-facing slopes to help nudge along the ripening process—the varietal is notorious for the time it needs to reach the level of phenolic ripeness required for the big, brooding, spicy, age-worthy reds for which the appellation is famous. Even so, the vines cling desperately to the slopes, making mechanical harvesting impossible. But hand-gathering is preferred in any case, ensuring a finer selection of grapes, in better condition and with smaller yields.

Meanwhile, the variety itself seems custom-designed for Bandol; Mourvèdre is an upright bush vine that forms a short stumpy trunk that will stand up to the Mistral winds. Bandol growers give preference to goblet pruning in order to reduce the amount of foliage and to help the low-producing vine bear triangular bunches with small, tight grapes bunches.

The Vigneron’s Savoir-Faire: Hard Road to Balance

To say that Bandol’s climate is ideal for Mourvèdre is not to say that growers have a smooth path to success: On the contrary, constant vigilance is table-stakes for successful winemaking operations; understanding the AOP regulations is a task in itself; following them is that much harder. For example, young vines intended for the production of red wines are not allowed to contribute until the eighth leaf has appeared on their trunk, and from that point, during every stage of cultivation, yields are controlled. Vine density must be at least 5,000 per hectare while spur pruning (leaving two-bud spurs on the trunk) is required. Chaptalization (adding sugar to unfermented grapes to increase the wine’s alcohol content) is banned, as is ‘any enrichment or concentration operation, even within the limits of the legal prescriptions in force.’

Things don’t get any easier in the cellar. Technology may have lightened certain workloads, allowing better control and new progress in quality, but the old ways reign supreme. Maturation is an essential factor in red wine production, and here, the vigneron’s know-how is irreplaceable. The primary goal in producing Bandol is to achieve balance through a process of slow, natural stabilization, and at each stage, wines are carefully selected and tasted and are accepted only if they meet the requirements of their status. A blind tasting test is carried out in June of the first year following harvest to allow the wine growers to examine the evolution of the vintage. It’s considered a ‘mock exam’ from which each wine grower learns critical lessons.

Future Classics in a Tuck-Away Pack

6 Bottles – $299 (Vintages 2021-2017)

Buying wine with the understanding that it will improve over time is like investing in stock futures: An examination of all the factors involved in the complicated process of wine maturity is vital. Not every Bandol from these four vintages are guaranteed longevity, but the ones we have assembled in this grouping have a high probability of improvement over the years—the result of terroir, the specifics of the growing season, and most importantly, the skill of the winemaker. Our trust in the latter is, though experience, impeccable.

Notes on The Vintages

2021 — Bandol in Minor Key

Subtle, restrained, nuanced, savory and earthy.

——————-

An up and down vintage by all accounts, with late frost, early rain, middle-August heat and a quick spike in potential alcohol created conditions that produced Bandol reds with less potency than 2020, but plenty of nuance—savory herbs, iron and earth. Yields were down 20% to 25% from the previous harvest, which was already small, but the wine shows the potential for considerable improvement in the cellar.

2020 — Bandol in Full Voice

Bold, complex, powerful, built to last.

——————-

Significant rain in June and July allowed most of Bandol’s vines to skate through an extremely hot August without much stress. Grape sugars skyrocketed, however, necessitating a careful and fairly rapid harvest. Reds from this vintage show a signature reduction reminiscent of wines from the 1990s, adding complexity and signaling wine that will age well.

2019 — Bandol in Deep Harmony

Rich, resonant, firmly structured, long aging.

——————-

After a humid 2018, Bandol dried out, with hot conditions throughout the summer, significant sunshine and the welcome return of the Mistral wind helping to prevent mildew and concentrating juice behind thick Mourvèdre skins. These wines are rich and deep, exhibiting firm, ripe tannins and the capacity for long aging.

2017 — Bandol in Allegro

Quick tempo, early harvest energy, bright and brisk.

——————-

The third year of summer drought in Bandol meant small berries, small bunches and reduced yields; the harvest was 18% down from 2016. The early season and bright, hot summer also meant an extraordinarily early harvest, beginning August 11th in some places, and at least two weeks ahead of the previous average for warm or hot years. Tempier in Bandol began harvest on August 22nd and finished on September 12th, and was very pleased with the quality, suggesting that the Mistral had been critical in ensuring freshness in the fruit, and that the winter rains had also kept the vines healthy during the long, hot summer.

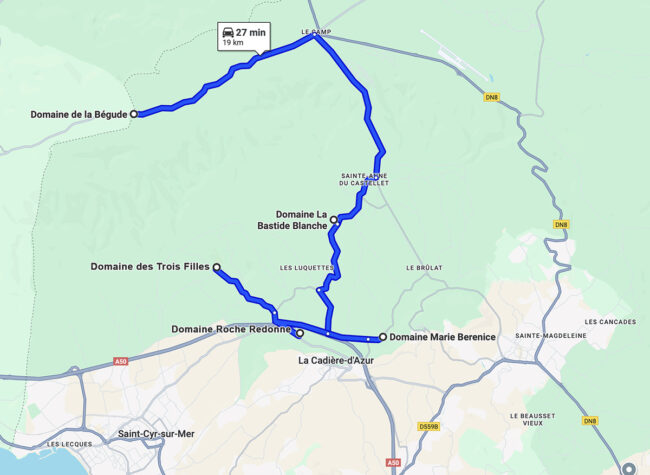

Domaine Marie Bérénic

Bandol at Its Primal Best

The first time Lyle Railsback, wine importer at France+Western tasted a bottle of Domaine Marie Bérénice, he exclaimed, “This Bandol Rouge has the aromas of Mourvèdre as thrilling as anything in Provence. And as exciting as older, cellared examples of Bandol can be there is something so captivating and primal about drinking a Bandol red on release, in its youth.”

As Domaine de Trois Filles was named for the daughters of the original owner, so is Domaine Marie Bérénice a tribute to Damien Roux’s daughter. Marie Bérénice was born into a long line of grape growers in Bandol, although historically the family sold their fruit to other estates. Damien, who made wine for another winery in the area, decided to begin releasing under his own label. The family farm, between the villages of La Cadière and Castellet and only a stone’s throw from the fabled beaches of Saint-Tropez, consists of 35 acres of clay and limestone terraces, where the work, done by hand, is certified organic.

In the cellar, Damien vinifies using wild yeasts and relies on long macerations. He ages his reds in large foudres for eighteen months before bottling without any fining or filtration.

1 Domaine Marie Bérénice, 2021 Bandol ($33)

1 Domaine Marie Bérénice, 2021 Bandol ($33)

90% Mourvèdre and 10% Grenache. Pie spices and leather lend a savory profile while the fruit is filled in with vibrant notes of cranberry, blackberry and cassis, with cedar, and tobacco appearing on the finish.

2 Domaine Marie Bérénice ‘Les Faremberts, Cuvée Simone’, 2021 Bandol ($36)

2 Domaine Marie Bérénice ‘Les Faremberts, Cuvée Simone’, 2021 Bandol ($36)

A collaboration between importer Lyle Railsback and Marie Bérénice’s winemaker Damien Roux, representing Damien’s oldest vines in a lieu dit known officially as ‘Les Faremberts’ but locally as ‘Chagall’ as the vineyard itself surrounds a family homestead owned by artist Marc Chagall. 90% Mourvèdre, 10% Grenache, the wine underwent a long maceration followed by 18 months in large oak barrels. A great, old-style Bandol showing cedar box, baking spices, blueberries and leather.

Domaine des Trois Filles

Bandol Takes Root in a New Generation

Audrey Arlon, current winemaker at Domaine des Trois Filles is one of the filles. The estate was named for her and her two sisters (Léonie and Justine) by their parents. Now, after having learned the craft and honed her skills at Domaine Ott and Domaine du Gros ‘Noré, Audrey has taken over her family’s vines in La Cadière-d’Azur.

“We farm 22 acres of old, goblet-trained vines co-planted with rye, fava beans, clover and radish sprout in between the rows,” Audrey explains. “This begins the process to combat global warming and keep the soil healthy. In the spring, we fold the cover crops into the earth to protect the soil while keeping humidity and maintaining a low temperature in the increasingly hot weather of Southern France. Giving natural aeration to the roots and better development of earthworms, we can to limit the spread of weeds, create greater biodiversity, and promote microbial life in the soil.”

Trois Filles is a family affair, and with the three sisters at the helm, it presents some interesting challenges. Audrey admits that it can be a struggle to balance the demands of motherhood with winemaking: “There are times, such as harvest, that require one’s full and undivided attention. And yet, from a physical point of view today, the evolution of the equipment allows us to force ourselves less, so we can do almost anything.”

3 Domaine des Trois Filles, 2020 Bandol ($33)

3 Domaine des Trois Filles, 2020 Bandol ($33)

75% Mourvèdre, 20% Grenache and 5% Cinsault from goblet vines grown on a clay-limestone hillside. Hand harvested into crates, gently macerated with native fermentation in stainless steel and aged in barrels for 18 months. A muscular core of earthy dark fruit is highlighted by classic leather, garrigue, underbrush and sweet black raspberry notes.

Domaine Roche Redonne

Bandol Anchored in the Hills, Bathed in Garrigue

Founded in 1979 by Henri and Geneviève Tournier, Roche Redonne is situated among the Bandol foothills surrounded by olive groves and garrigue scrub just outside the pretty village of La Cadière d’Azur.

The 30-acre vineyard is farmed using organic methods and the vines now average more than 40 years in age, with the youngest vines at 20 years and the oldest at 60. The yields are kept low, and, in fitting with the appellation laws, the steeply hilled vineyards is harvested by hand.

Their son, Guilhem Tournier, has followed in their footsteps, creating his own estate (Château Guilhem Tournier) in 2004 and is now fully certified organic and he uses biodynamic methods.

4 Domaine Roche Redonne ‘Cuvée Les Bartavelles’, 2019 Bandol ($71)

4 Domaine Roche Redonne ‘Cuvée Les Bartavelles’, 2019 Bandol ($71)

‘Bartavelles’ means ‘Royal Partridges,’ and it certainly presents a noble expression: 95% Mourvèdre and 5% Grenache grown on a blue marl base with a layer of clay on top. The wine offers a fruity aroma with a hint of smoke; the palate is filled with cherry compote and sweet spices, leading to a full, textured finish of exceptional length.

Domaine La Bastide Blanche

Bandol on the Rocks, at the Edge of the Sea

Michel and Louis Bronzo purchased Bastide Blanche in the ‘70s in the belief that the terroir could produce a wine to rival those of Châteauneuf-du-Pape. With that in mind, the brothers planted Carignane, Cinsault, Clairette, Grenache, Mourvèdre and Syrah. Vintage 1993 proved to be their breakaway year, putting both Bandol and themselves on the wine map. The estate is located in the foothills of Sainte-Baume Mountain, five miles from the Mediterranean Sea on land that is primarily limestone scree.

Bastide Blanche has been certified Biodynamic since 2020. According to Louis Bronzo, “True to our terroir, all our wines are organic and Biodyvin certified. To preserve nature and protect everyone’s health, we work tirelessly to improve our farming practices. We owe the earth our loyalty, especially since we have blessed with our environment, at the foot of the Sainte-Baume mountain, just a few kilometers from the Mediterranean Sea. Our soil is predominantly limestone, which is ideal for our dozen grape varieties.”

Michel adds, “As is required of Bandol producers, all our grapes are harvested by hand—a practice that makes it possible to finely sort the bunches during harvest and to better protect the fruit until it reaches the cellar.”

5 Domaine La Bastide Blanche, 2019 Bandol ($34)

5 Domaine La Bastide Blanche, 2019 Bandol ($34)

Predominantly Mourvèdre (around 73%) with smaller contributions by Grenache, Cinsault, Syrah and Carignan, the wine is Bandol-big with crushed blackberries, raspberries and warm cherry pie. Lively, mouthwatering and concentrated with great mid-palate intensity.

Domaine de La Bégude

Bandol on High Ground

Located at the highest point in Bandol (1400 feet) La Bégude was once a stopover inn on the road from Marseille to Toulon, a shelter for the night where you could find ‘beguda’—the local Provençal wine with a name drawn from the Catalan language.

The Roulleau family purchased Domaine de La Bégude in 2022, making them only the fifth family to own the estate since the Middle Ages. Appointing Laurent Fortin as Managing Director. According to Fortin, the goal in overseeing the estate is “To keep the same pioneering spirit while daring to break the codes to offer a unique vision of wine in the heart of this exceptional vineyard.”

Fortin, who has managed Roulleau-owned Château Dauzac since 2016, says, “The Roulleau family fell in love with this site, these exceptional terroirs set in the garrigue and these wines with strong personality. We are following in the footsteps of the Tari family to make La Bégude shine at the top of the Bandol appellation. The challenge is exciting, in the continuity of Château Dauzac, to build a family group of inspired vineyards.”

The synergy between the Tari and Roulleau clans has been immediately apparent, both in viticultural dynamism and in the spirit that shares the common value of respect for nature and biodiversity. Under the Tari family, Bégude was a place of natural agro-forestry, home to the International Conservatory of Mourvèdre, which farms an exceptional vine collection of 150 Mourvèdre varieties, the largest in the world. Going forward, the intention is to reinforce and maintain this collection.

The estate itself encompasses more than 1200 acres, of which 75 are under vine—65% Mourvèdre, 25% Grenache and 10% Cinsault, now at an average age of 25 years. The vineyards sit at elevations exceeding 1300 feet, and as such, are among the highest in the appellation. The plan is to increase the cultivation to 100 acres over the next few years and to continue to produce Bégude’s hallmark rich, acidic, fruit-driven wines that develop in the cellar with elegance. The Roulleaus are proud to age their own wines in the old chapel of Miséricorde of Conil, dating from the 7th century—a vestige of the presence of the Abbey of Saint Victor on the estate.

6 Domaine de la Bégude ‘La Brulade’, 2017 Bandol ($99)

6 Domaine de la Bégude ‘La Brulade’, 2017 Bandol ($99)

95% Mourvèdre, 5% Grenache grown on clay marl. ‘La Brulade’ is the name of a select slope located at an altitude of 1300 feet overlooking the Mediterranean Sea between La Baie d’Amour in the south and La Sainte Baume in the north, one of the highest parcels in Bandol; the wine is only made in exceptional vintages. With 24 months of foudre aging behind firm and tannic fruit, the wine is dark and brooding and shows blackberry, boysenberry, licorice and peppery garrigue. It should continue to develop nuance for years to come.

Bandol Matured, Time Realized

Superlative winemaking involves a formula that’s part science and part soul. It’s not a stretch to liken the process to a recipe, and so a comparison of a great wine with the steps required to produce a perfectly prepared, top-end Wagyu ribeye steak is appropriate. Like wine, an exceptional piece of beef traces its origins to the earth itself: Wagyu cattle are pampered from birth, fed a high-protein diet, often massaged and given beer to encourage marbling.

Likewise, the vineyards that produce top quality wines enjoy both breeding and babying; adding to the natural elements is a cycle of biodynamics to mollycoddle microbic life, with the correct attention paid to moisture, food and pruning. While in the growth stage, all possible care is taken so that the vines do not fall prey to disease or mismanagement.

The same holds true for the steer. And for both, some aging is required before premium flavor is said to be reached. For the Wagyu, this may be as long as four hundred days at 34°F; for the aged Bandol’s in this week’s package, the wine wettest behind the years is eight years old; the most mature, 15.

Of course, for both beef and bottle, the consumer is the ultimate benefactor and the decisive judge; the time the wine spends maturing toward an ‘ideal’ state is the time the steak spends over the flame. This is, of course, an optimal and somewhat measurable period depending on individual tastes, but a given consensus can certainly be formed and debated.

A gustatory exploration of these wine selections (which happen to pair very well with beef) bears witness to the evolution of Mourvèdre and Cinsault and to a lesser extent, Grenache and Syrah in Bandol’s changing climate. The sensory profile of this blend has developed a kaleidoscope of tertiary flavors and scent developments.

Provenance is guaranteed for these wines, of course, so you know that storage conditions have been optimal.

Notes on The Vintages

2016 — Bandol in Sustained Note

Concentration, freshness, built for endurance and the long haul.

——————-

Aside from a minor frost in April, the main growing-season challenge was drought: in Bandol, fewer than eight inches of rain throughout the entire season. The result was a reduction of yields of 10 to 30%. The quality of both white and (especially) red wines, though, was high since the summer heat was tempered by cool nights and the grapes retained fresh acidity, while the lowered yields provided impressive concentration of flavor. These are wines for the long haul.

2015 — Bandol in Allegretto

Balanced, graceful, approachable yet with poise.

——————-

The second wet winter in a row raised water tables to herald a warm, dry spring. Bud break took place earlier than usual and flowering went well; summer was generally warm but without excessive heat—the rain that fell on June 15th was helpful. The conditions of steady, tempered heat continued throughout August clear skies; Bandol reds are outstanding. Drink now, or hold for a few more years.

2013 — Bandol in Andante

Measured pace, delicacy, freshness, middle-weight charm.

——————-

After a long, cool and slow spring, the entire growing season—bud break, flowering, véraison and harvest—was about two weeks later than usual. There were a few hail storms in June, but the disease pressure of early summer gradually abated thanks to the Mistral as September approached. It was a good vintage for those who long for delicacy and freshness in white and rosé wines, but the reds tended to be middle-weight and are probably at their peak.

2011 — Bandol in Counterpoint

Contrasts resolved into structure, now showing maturity.

——————-

A dry, sunny spring led to ideal flowering, but the summer was uneven with a cool wet July, dry conditions from mid-August to mid-September. Then welcome rain fell followed by drying Mistral wind. Cool nights during harvest led to Bandols being particularly successful & structured; best required cellaring and are now coming into their own.

2010 — Bandol in Adagio

Late harvest, spice and finesse, graceful and nuanced.

——————-

Bandol saw more rainfall than recent years with sporadic flooding in June. Alternating sun/rain in October resulted in late, extended harvest led to Bandol reds with much spicy finesse and definition.

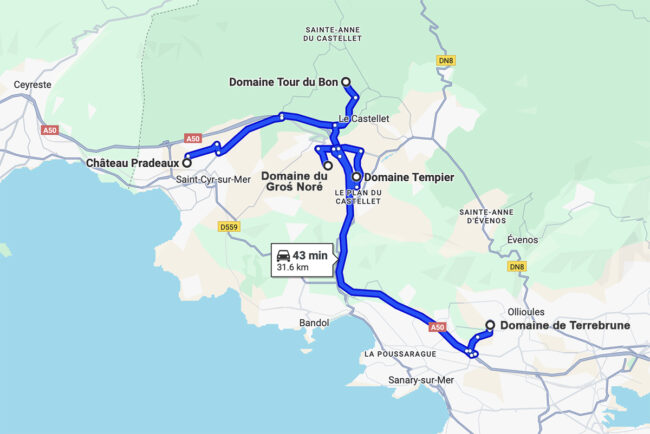

Château Pradeaux

Resolutely Old School

Situated on the outskirts of the town of Saint Cyr-sur-Mer, directly on the Mediterranean between Toulon and Marseilles, Château Pradeaux has been in the hands of the Portalis family since the French Revolution. In fact, Jean-Marie-Etienne Portalis helped draft the Napoleonic Code and assisted at the negotiation of the Concordat under Napoleon the First. Today, the domain is run by Cyrille Portalis, who continues to maintain the quality traditions of his forbears, assisted by his wife Magali, and their sons Etienne and Edouard. Although vineyards are planted almost exclusively to old-vine Mourvèdre, Château Pradeaux Bandol Rosé is composed of Cinsault as well.

Château Pradeaux, 2015 Bandol ($67)

Château Pradeaux, 2015 Bandol ($67)

95% Mourvèdre, 5% Cinsault. In contrast to the three years preceding it, the 2015 vintage yielded a classic and deeply typical Pradeaux Bandol: a wine of grainy, spicy fruit, medium in weight but rippling with underlying power, and with an intoxicating aromatic overlay of violets and smoked meats.

Domaine de Terrebrune

Bandol’s Creed of Soil and Soul

Owning a winery may be the whispered dream of many sommeliers, but Georges Delille put his francs where his mouth was. In 1963, he bought an idyllic property in Ollioules, just east of Bandol, framed by the Mediterranean and the Big Brian mountain (Gros-Cerveau). The site was dotted with olive groves and scenic views, but no vines. Georges spent ten years renovating the property; he terraced hillsides, refashioned the masonry, replanted vineyards following the advice of Lucien Peyraud, designated soils to lie dormant and regenerate, and built a new cellar. In 1980, his son Reynald joined him after attending winemaking school, and together they launched their first bottled vintage of Domaine de Terrebrune, which Reynald named in honor of the rich, brown soils they farm.

There is plenty of diversity in this soil, though. Throughout Terrebrune’s 75 acres, beneath the layers of clay and earth, blue, fissured limestone is at work, lending a more noticeable minerality to the wine. Reynald’s personal credo of “Philosophy, rigor, and respect” is not a catch-phrase, but an ideology for living.

Domaine de Terrebrune, 2016 Bandol ($64)

Domaine de Terrebrune, 2016 Bandol ($64)

85% Mourvèdre, 10% Grenache, 5% Cinsault grown in limestone-pebbled brown clay above blue limestone bedrock. A full-bodied dose of Terrebrune terroir that should continue to mature and drink well for another two decades. Shows blackberries, dark cherries and cedar with hints of black pepper, game, licorice and dark chocolate.

Domaine Tempier

Bandol’s Single Vineyards, Etched in Stone

Robert Parker Jr. once referred to Domaine Tempier’s rosé as ‘the world’s greatest’, but the backstory isn’t bad either: Gifted the property by her father in 1936 upon her marriage to Lucien Peyraud, Lucie ‘Lulu’ Tempier found herself the owner of an active Bandol farm near Le Plan du Castellet that had been in the family since 1834. Her husband did extensive research into the terroir, and immediately halted the ongoing effort to tear out Mourvèdre vines in favor of higher-yielding varieties. In went new Mourvèdre, some of which are still producing.

With the assistance of neighboring vignerons, Lucien worked with the I.N.A.O. to establish Bandol as its own AOC, whereupon a large-scale replanting of Mourvèdre ensued across the region. As a result, Lucien will forever be celebrated as the Godfather of Bandol as well as the man who revived Mourvèdre to its former glory. Part of that glory includes their three single-vineyard releases, La Migoua, La Tourtin, and Cabassaou.

Domaine Tempier ‘La Migoua’, 2016 Bandol ($110)

Domaine Tempier ‘La Migoua’, 2016 Bandol ($110)

50% Mourvèdre, 20% Grenache, 26% Cinsault, 4% Syrah. La Migoua’s terroir mainly consists of heterogeneous clay that varies in color between red, ochre, and blue. Located at 885 feet, it is the highest altitude vineyard among all of Tempier’s sites. The 60 acres are bordered by garrigue and pine forest, and the grapes yield earthy, gamey wines. La Migoua has the smallest proportion of Mourvèdre in the blend, with the highest percentage of Grenache among the three cuvées.

Domaine Tempier ‘Cabassaou’, 2016 Bandol ($160)

Domaine Tempier ‘Cabassaou’, 2016 Bandol ($160)

95% Mourvèdre, 4% Syrah, 1% Cinsault. At 4 acres, Cabassaou is the smallest Tempier vineyard, but with the oldest vines, now surpassing fifty years. It sits lower on the hillside where it is protected from the strength of the Mistral, enjoying temperate breezes and maximum sunshine, which is evidenced by is ripeness, density and power in the wines.

Domaine Tempier ‘La Tourtine’, 2016 Bandol ($110)

Domaine Tempier ‘La Tourtine’, 2016 Bandol ($110)

80% Mourvèdre, 10% Grenache, 10% Cinsault. La Tourtine sits just above Cabassaou, where the soil is more homogeneous and rich with clay. As a result, the 30-acre La Tourtine produces powerful, tannic wines with gorgeous fruit character.

Domaine du Gros ‘Noré

Mourvèdre with Muscle

‘Gros’ means big, but as for ‘Noré, the translators are silent. But ‘big’ is the operative word anyway since it describes the proprietor in body, mind and legend. A former boxer and an avid hunter, Alain Pascal spent many years as a grower who sold his Bandol fruit to Domaine Ott and Château de Pibarnon. Along with his father, he bottled wine for family consumption only. But in 1997, after his father’s death, Alain launched Domaine du Groś Noré, and now, along with his brother Guy, bottles 5000 cases annually drawn from his forty acres of prime Cadière d’Azur vineyard.

The brothers work within the strictures of the region and often, beyond them, leaving the grapes to mature fully on the vine, lending great intensity to the fruit, and where appellation law demands that each blend includes at least 50% Mourvèdre, Alain ups the assemblage ante to 80%. The wine reflects the man; big and bold up front, while underneath is a core of character—depth, complexity, soul and finesse.

Domaine du Gros ‘Noré, 2011 Bandol ($98)

Domaine du Gros ‘Noré, 2011 Bandol ($98)

80% Mourvèdre, 15% Grenache, 5% Cinsault. The 35-acre vineyard contains vines of about 30 years in age. With a decade under its belt, the harsh tannins have softened and the wine has given over its aggressive fruit to cool notes of eucalyptus and fresh fennel.

Domaine du Gros ‘Noré ‘Cuvée Antoinette’, 2013 Bandol ($120)

Domaine du Gros ‘Noré ‘Cuvée Antoinette’, 2013 Bandol ($120)

95% Mourvèdre, 5% Cinsault/Grenache. A beautiful blend with hints of underbrush and mushroom behind the dark red fruits and spice. The tannins are resolved and the acidity is suitably tempered.

Domaine du Gros ‘Noré ‘Cuvée Antoinette’, 2010 Bandol ($130)

Domaine du Gros ‘Noré ‘Cuvée Antoinette’, 2010 Bandol ($130)

95% Mourvèdre, 5% Cinsault/Grenache from a small, two-acre vineyard. Black cherry and stewed plum notes remain to enliven balsa, tobacco, game, graphite and iron.

Domaine de la Tour du Bon

A Lyrical Bandol From the Heights

Sitting pretty at an elevation of 500 feet on 35 acres of red earth, clay, sand, and gravel over a sturdy limestone plateau in Le Brûlat du Castellet in the northwestern corner of Bandol, Domaine de la Tour du Bon is the culmination of commitment and sweat equity. The property, cleared by plough, has been a full-time farm since 1925 and has been worked by the Hocquard family since 1968. At the helm is Agnès Henry, who spent a number of years at the apron strings of a hired winemaker, but when she decided to approach the job herself, she found that her person expression of terroir was quite unique. The wines she claims as her own have both power and precision in equal measure, but effectively display the finesse and charm of her lyrically named vineyards, La Rémoise (The Dweller), Saint Ferréol (a local saint), Ensoleillade (Place Bathed in Sunshine), Clos des Aïeux (Clos of the Forefathers), l’Aire (the Aerie) and Bellevue (Beautiful View).

Domaine de La Tour du Bon ‘En Sol’, 2017 IGP Méditerranée ($85)

Domaine de La Tour du Bon ‘En Sol’, 2017 IGP Méditerranée ($85)

A half-acre site produces this extraordinary non-blended Mourvèdre, but since it breaks Bandol AOP regulations requiring a two-grape minimum, Henry has chosen to declassify the wine and release it as IGP Méditerranée. Grippy yet accessible tannins underscore flavors of ripe dark fruit, berries, scorched earth and a touch of smoked meat.

Notebook …

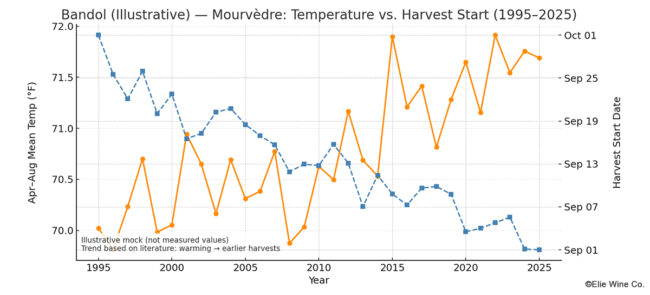

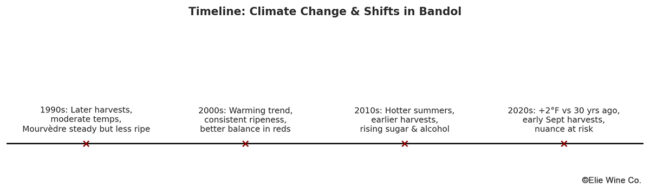

Mourvèdre in the Hot Seat: Bandol and the New Provence

For as long as anyone can remember, Bandol has been the outlier of Provence. Where the rest of the region turned its vineyards into a factory of pale, pool-side rosé, Bandol doubled down on Mourvèdre—a grape that doesn’t like to be rushed and doesn’t care if you’re impatient. It needed heat, sun, and time. Plenty of time.

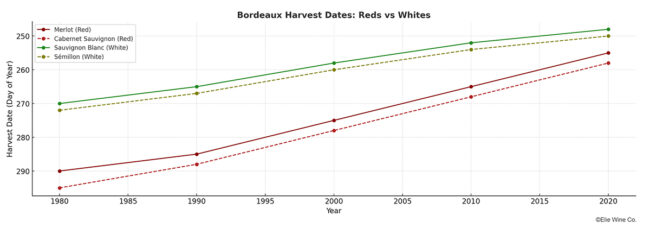

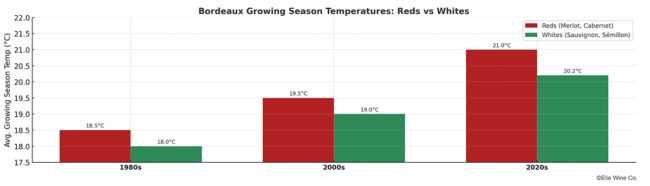

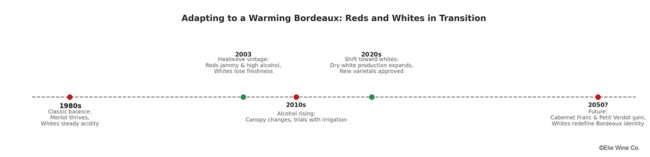

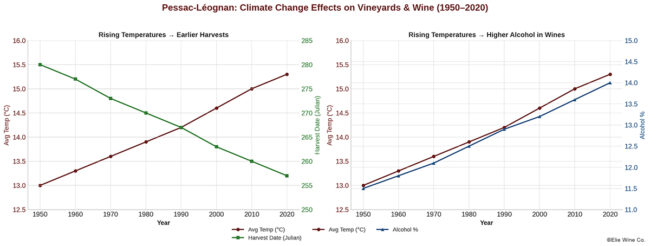

That was then. Now, thanks to climate change, Bandol has more heat than it knows what to do with. Harvest comes weeks earlier, sugars spike, and bottles that once clocked in at 13% creep toward 15%. What used to be a wrestling match to ripen Mourvèdre has become a struggle to rein it in.

The New Reality Check

Bandol’s growers are staring down a paradox. Mourvèdre—once the slowpoke grape that barely made it to the finish line—is suddenly sprinting. Power is easy. Balance? That’s the endangered species. And the vineyards themselves are thirsty. Longer droughts stress even Bandol’s famously deep-rooted old vines, while the rain, when it does come, arrives as a downpour that chews up terraces and washes away topsoil.

Rosé Isn’t Immune

Even Bandol’s rosé, the muscular cousin of Provence’s whisper-pale styles, is shifting. Deeper colors, bigger fruit, the kind of aromatics that read more tropical cocktail than Provençal picnic. Some drinkers cheer the intensity; others miss the quiet elegance that once defined Bandol’s pinks.

Coping Mechanisms

Growers are improvising. Taller canopies to shade the bunches. North-facing sites and higher altitudes to slow things down. A little more Grenache or Cinsault in the blend to sand down Mourvèdre’s rough edges. Longer élevage in big foudres to bring back some discipline.

Bandol on the Edge

The question hanging over all of this: What does Bandol look like in 20 years? A Mediterranean powerhouse pushing 16% alcohol, or a region that manages to bend without breaking, reinventing itself while staying true to its granite-jawed personality?

Bandol has always been about tension—between sun and wind, fruit and tannin, pleasure and patience. Climate change doesn’t erase that tension; it cranks it up. The wines may be louder now, but they’re still telling the same story: Mourvèdre doesn’t compromise, and neither does Bandol.

- - -

Posted on 2025.09.18 in Bandol, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Provence | Read more...

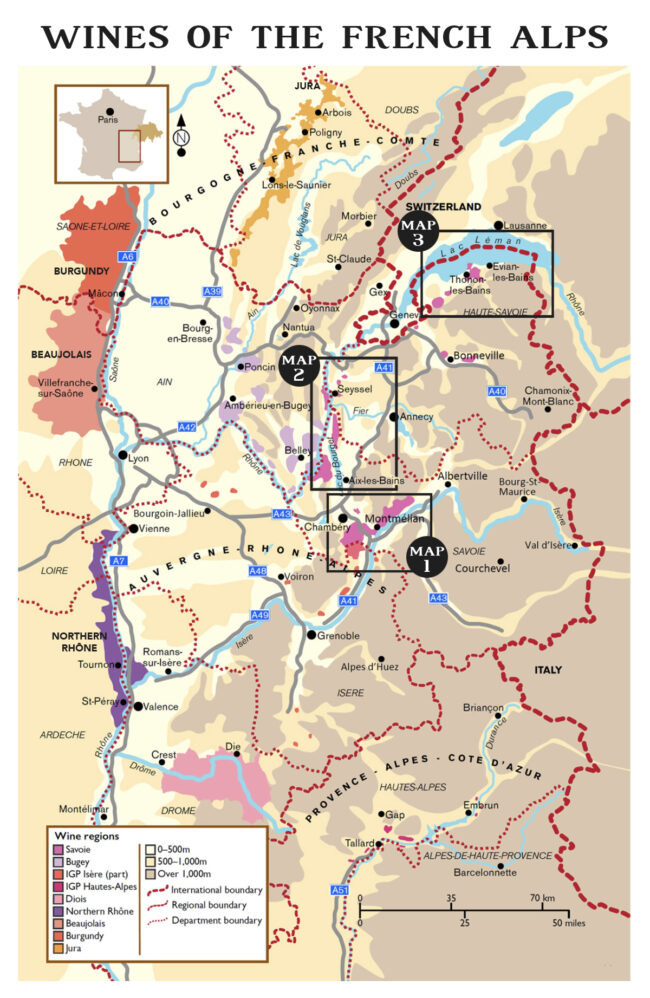

Savoie Fare: Father-and-Son Duo Jean-Noël & Thomas Blard Craft Distinctive, Instantly Appealing Wines from Rare Alpine Varieties in France’s Mountainous Savoie Region 7-Bottle Red, White & Sparkling Sampler – $279

Italy is one giant vineyard, cuff to heel, but in France, wine regions are like fireflies in a midnight garden; they light up isolated corners. The brightest fireflies command most of the attention, of course, and as a result, the highest price points. But Savoie—in the far eastern part of France where the Alps spill over from Italy and Switzerland—is one of most remarkable of the glimmers.

The White Stuff: A Golden Opportunity Leads to Wine Revival

According to Wink Lorch, an avid skier and arguably Savoie’s most vocal champion, the development of the post-war ski industry represented a turning point for the region’s popularity: “This created new customers for its wines, of which very little get exported. Even so, up until the 1970s, there were hardly any vine-growers who lived solely from their vines.”

Reconquering the Slopes

Over the past twenty years, however, a new wave of independent vignerons has been boosted by organizations dedicated to preserving the singular grape varieties of the region, and Savoie has finally begun to come into its own.

Alpine wines have a crunchy sizzle and a cool sappiness unlike wine from anywhere else. Not only that, but the predominant grapes don’t show up on many other radars, so the unique textures commingle with a whole new flavor profile to surprise and delight the palate.

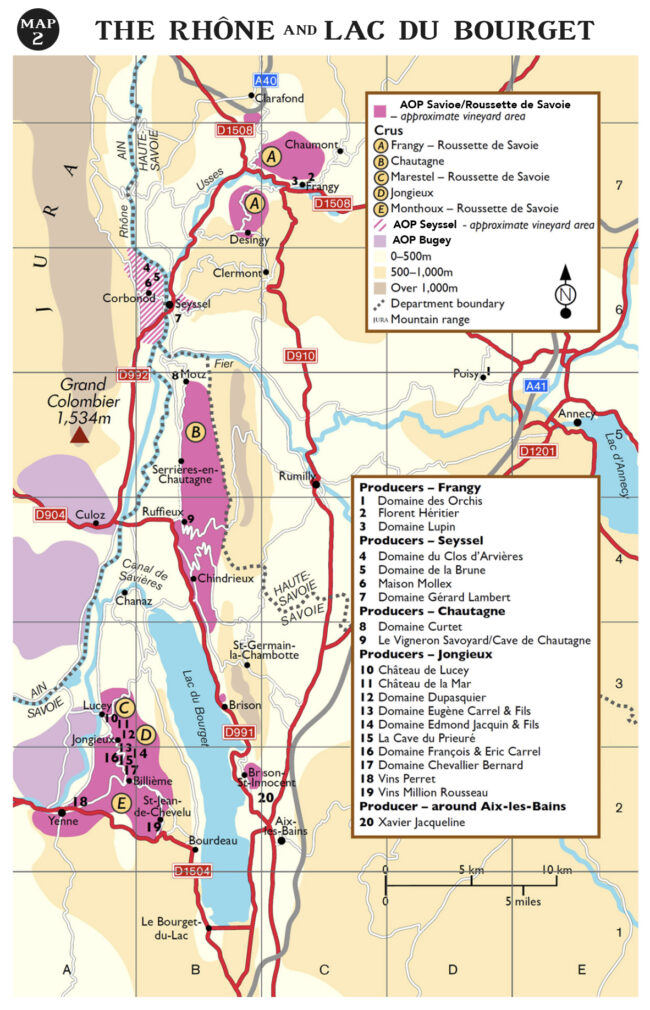

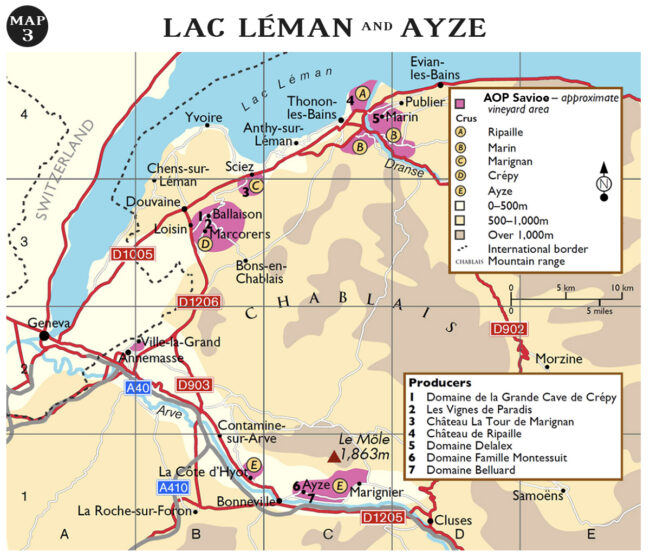

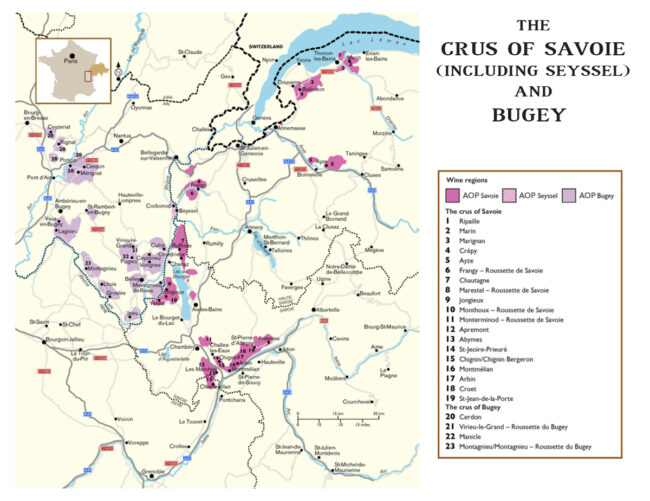

For the historically inclined, Savoie was the point where Hannibal crossed the Alps en route to Rome; for vinophiles, Savoie encompasses two main sub-appellations—Bugey, with 1250 acres of vines and Vin de Savoie, or simply Savoie AOP, which includes Roussette de Savoie and Roussette du Bugey. There are also 17 Vin de Savoies Crus and four Roussette de Savoie Crus, whose name may appear on labels. Most Savoie vineyards are planted on steep, south facing slopes, where favorable sunlight exposure and excellent drainage make for perfect ripening conditions despite the cold continental climate. The presence of lakes Bourget and Geneva, as well as the upper Rhône River, further moderate the climate. Most Vin de Savoie vineyards are found on limestone-based soils, which is adept at storing heat during the day and reflecting it back onto the vines at night.

Wines That Refresh Like Mountain Air: The Cool Signature of Alpine Terroir

Metaphors linking wine to its place of origin are the stuff of poetry, but they’re also the foundation of terroir. Among the most common descriptors of high-altitude wine is ‘refreshing’ which is an offhand way of saying that they tend to be lower in alcohol and higher in acidity than valley wines. These acids are often the end result of the cool mountain air which they resemble, giving distinct, cleansing mineral characteristics to the wine with citrus and herbs rather than jammy fruit.

Savoie’s Natural Balance: Interplay Between Acidity and Lightness

That said, it is sometimes a challenge for winemakers to reign in mountain-borne acid and to keep it from running away with the profile. Tart is acceptable—sour is not. Without delving into too much chemistry, the predominant acids found in wines are tartaric, malic, citric and succinic, and all but the last occur naturally in grapes—succinic acid is produced by yeast during fermentation. In areas where long hang-times for grape bunches to develop sugars and tame acidity are not possible in the mountains, and winemakers will occasionally resort to artificially manipulating the juice, the must, or as a last resort, the finished wine.

These are not wines we embrace at Elie’s, preferring those that display natural balance, favoring the expression of terroir over excessively extracted fruit with high sugar levels. Adjusting acid rather than preserving it defies one of winemaking’s oldest adages: ‘Good wine is made in the vineyard, not in the cellar.’

The wines of Savoie (even the reds) tend be light and somewhat playful on the palate, filled with alacrity and crackle and with correspondingly low alcohol levels to match an ethereal mountain finesse. Yet, we have found many wines of Blard & Fils that seek to take traditional Savoie varietals to the next level, busting through the clichéd ‘Ski & Raclette’ ceiling to create sophisticated wines suitable for the most refined tables.

Seven-Bottle Sampler Pack $279

The wines in this 7-Bottle Sampler Pack represent one of Savoie’s icons and iconoclasts, Thomas Blard, who has taken the management reins from his father Jean-Noël. They represent the wide array of native grapes and their associated flavor profiles that are typical of this hinterland of marvels.

Setting the (Appellation) AOP Scene:Savoie & Roussette de Savoie

Located in the foothills of the vast Alpine ranges of Switzerland and Italy, Savoie AOP grows grapes at altitudes between 800 and 1800 feet. Savoie’s 11,300 acres of scattered vineyards are responsible for less than 0.5% of the wine produced in France, and of the 3 millions of wine made in Savoie every year (compare this to Bordeaux’s 158 million), only about 8% of it is consumed outside the appellation. Although even the highest vineyards are at foothill-elevation, the region is distinctly alpine, with towering white-capped mountains and pristine lakes dominating the surrounding terrain: Mont Blanc, France’s tallest peak at 15,000 feet, has a Savoie zip code. The vineyards are adapted to this environment, growing occasionally on 80-degree slopes. Ranging from rocky subsoil to sand (sometimes in the same vineyard) the Savoie terroir supports 23 different grape varieties.

A large portion of western Savoie falls under the sub-appellation Roussette de Savoie. Encompassing four Cru communes—Frangy, Marestel, Monterminod and Monthoux—Roussette wines are dry and made from the Altesse grape, here is called ‘Roussette.’ The name is a reference to the reddish tint that the grape acquires before harvest.

In the past, Chardonnay made up to half the content in Roussette bottlings, but the practice was outlawed in 1999.

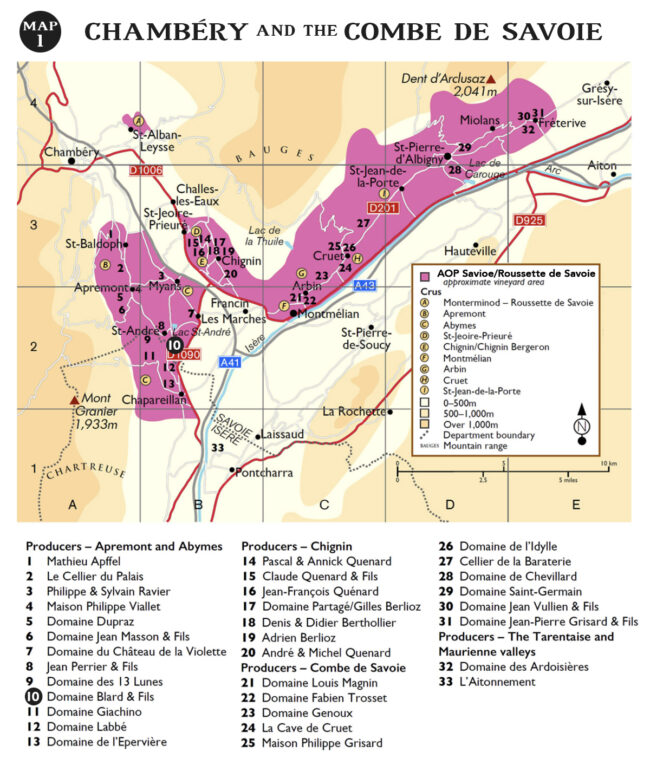

Domaine Blard et Fils

Abymes, Apremont, Arbin, Roussette de Savoie

Apremont is perhaps the best known white wine Cru in Savoie. Surrounding the tiny village of Apremont, just south of Chambéry, the vines make up one of the most southerly Crus in the department. Apremont wines are made predominantly from the local Jacquère grape and are typically light and dry with floral, mineral characters.

In part, Blard & Fils is hard at work changing preconceptions about this terroir.

Jean-Noël and Thomas Blard are a father/son team who has taken their family domain to new quality heights while moving steadily toward fully organic and natural viticulture. In the 1990’s, Jean-Noël became one of the first vignerons in the appellation to diversify into Pinot Noir, and was also eager to raise the quality bar on Jacquère and Mondeuse—the latter by aging in neutral oak for a minimum of two years. With 25 acres under Blard control, grassed over and fertilized naturally, the Blards use a technique known as ‘intercep’ to remove unwanted greenery before finishing the job by hand.

Jean-Noël and Thomas Blard, Domaine Blard & Fils

Five generations of Blard have snatched victory from the jaws of defeat: In 1248, the side of Mont Granier (one of the major formations of the Savoie’s Chartreuse Massif) collapsed, and a wave of boulders and scree crushed the landscape below, forever changing the soil structure. Apremont means ‘bitter mountain’ and Abymes means ‘ruin’ and as a result of the natural upheaval, it is today it is considered to be the best place in the Savoie (and by extension, all of France) to grow Jacquère.

Altesse: Her Highness’ s Balancing Act

Nowhere in the world does Altesse reign as regally as in Roussette de Savoie, an AOP which has adopted the grape’s nickname ‘Roussette’ as its own. Late to ripen, and turning pink near harvest, the variety produces small grapes with a tight-bunch structure. Its most significant success is as a stand-alone varietal (chiefly in Roussette de Savoie and Roussette du Bugey), but it is also permitted as a minor blending component in the Jacquère-predominant Vin de Savoie wines.

The most likely origin theory is that Altesse is indigenous to the southern shores of Lake Geneva since it shares a close genetic link to the western Swiss workhorse Chasselas. Altesse is perfectly suited to the mountainous terroir around the western Alps in Savoie, and retains a high level of acidity while developing characteristic flavors of bergamot, hazelnut and almond. Such characteristics make it ideal for the production of sparkling wines as well and, consequently, Altesse is included in the region’s Crémant de Savoie wines and the sparkling Seyssel wines. Still Altesse wine is sometimes aged in oak and can age in bottle for up to five years.

1 Blard & Fils, 2020 Roussette de Savoie ‘Altesse’ ($27) WHITE

1 Blard & Fils, 2020 Roussette de Savoie ‘Altesse’ ($27) WHITE

100% Altesse from Abymes, from vines that are 35 years old. As always, Thomas Blard ferments naturally, with 20% of the juice seeing skin contact for 10 days. Aged on the lees for 10 months before bottling, the wine presents a terrific nose of green grass, salt, lemon and ripe apricot. The palate follows with green tea, lime zest, and herbs behind an exhilarating, Chablis-like texture.

Jacquère: Defined by Salinity and Minerality

Jacquère’s pedigree is 100% Français, and specifically Savoyard—at least, it’s impossible to find significant plantings outside the shadow of Mont Granier in the villages of Apremont and Abymes. The wines have characteristic cool-climate acidity vines and they write the book on the classic descriptors ‘mountain fresh’ and ‘alpine clean.’ Leaning toward the herbaceous with showers of freshly cut grass, green apples and pears, Jacquère is usually best when consumed young, while it still displays clean minerality and lively citrus palate.

It’s a high yielding vine, something that does not always lend itself to high quality. Since the 1980s, an attention to wine made from limited yields has resulted in wines with considerably more depth and weight, showcasing the region’s potential.

2 Blard & Fils ‘Cuvée Thomas’, 2021 Vin de Savoie Apremont ($29) WHITE

2 Blard & Fils ‘Cuvée Thomas’, 2021 Vin de Savoie Apremont ($29) WHITE

Cuvée Thomas is a blend of several different Jacquère parcels where vines are between 36 and 120 years old. Grown on clay/limestone soils seasoned with blue silex, the grapes are fermented on native yeast and aged ‘sur lie’ for nine months prior to bottling. The wine shows a delicate fresh almond bouquet above a foundation of crisp apricot and peach, with a mineral-driven palate that expresses textbook Jacquère salinity.

3 Blard & Fils ‘Alpin’, Crémant de Savoie Brut ($32) SPARKLING WHITE

3 Blard & Fils ‘Alpin’, Crémant de Savoie Brut ($32) SPARKLING WHITE

50-year old Jacquère (60%), Chardonnay (20%) and Pinot Noir (20%) vines from an ideally exposed south-east facing vineyard, the base wine was aged for eight months in a combination of barrels and vats; once bottled, this Brut-nature zero-dosage sparkler sees an additional 24 to 36 months aging. Disgorged January 2022.

Malvoisie: From Mistaken Identity to Savoie Original

Lesson one is offered by INAO, the organization that defines appellations in France: Malvoisie does not belong to the Malvasia family, which produces many forgettable wines throughout the Mediterranean, including Pinot Grigio. Instead, it is Frühroter, a cousin to Austria’s famous Grüner Veltliner. It resembles Pinot Gris on the vine, and since Malvoisie was not, until recently, approved for Savoie, many growers simply labeled their Malvoisie ‘Pinot Gris.’

The second lesson comes from Thomas Blard himself: “Our Malvoisie is the real deal; Frühroter Veltliner and never Pinot Grigio.”

Frühroter Veltliner wines tend to be somewhat herbaceous with light lemony characters and often a note of almonds. It is an early ripening grape susceptible to frost, which accounts for the prefix ‘früh’, which means ‘early’ in German.

4 Blard & Fils ‘Monemvasia’, 2019 Vin de Savoie ($32) WHITE

4 Blard & Fils ‘Monemvasia’, 2019 Vin de Savoie ($32) WHITE

Thomas Blard does not make ‘Monemvasia’ every year; it is entirely dependent on the success of the harvest. Instead, in some years, Thomas and Jean-Noël do a sweet wine from the grape using ‘passerillage,’ the technique of drying the grapes in ambient air to concentrate sugars.

2019’s ‘Monemvasia’ is dry. It originates from 10-year-old vines from three different parcels with a mix of clay and limestone soils where elevations average 1200 feet. The wine, which shows delicate cucumber, Meyer lemon, and crisp mineral tones, was vinified in stainless steel tanks and aged 12 months in stainless and from Crémant.

Mondeuse Noire: Savoie’s Distinctive Red with a Syrah Connection

Mondeuse Noire, commonly known simply as Mondeuse, is a grape with a distinctive personality. Having likely originated in eastern France, probably in or close to the region it now calls home, Savoie, it was once thought that Mondeuse was identical to the northern Italian grape Refosco as they both share similar botanical characteristics and flavor profile. DNA analysis has shown that they are separate varieties, while the same analysis revealed that Mondeuse is not a color mutation of Mondeuse Blanche, but is either its parent or offspring. The significance of this is that Mondeuse Blanche is one of the parents of Syrah, making Mondeuse Noire the grandfather of Syrah or half-brother to Syrah—something to keep in mind while tasting.

Like Syrah, Mondeuse offers violets, candied red fruit, dark berries, black pepper and spice enveloped in raspberry, blueberry, blackberry and plum with a bitter cherry and peppery finish.

5 Blard & Fils, 2020 Vin de Savoie Arbin ‘Mondeuse Noire’ ($34) RED

5 Blard & Fils, 2020 Vin de Savoie Arbin ‘Mondeuse Noire’ ($34) RED

The Blard winery is actually in the Apremont region of France but they are leasing some 50-year-old Mondeuse vines in Arbin. Grown in clay and limestone soils, there is a pronounced iron-rich mineral note to the nose, along with red fruit and a little green apple carrying through. Somewhat lacy on the palate but with grip.

Pinot Noir: Burgundy’s Standby Finds a Mountain Home

Though it makes up less than 7% of total Bugey plantings, Bugey is still the spiritual home for Burgundy’s red wine standby, and is the only legally allowable grape in red Bugey Cru Manicle. Manicle whites, like Burgundy, are made from Chardonnay. Manicle’s zone covers a small, south facing mountain slope on the southern apex of the Jura mountain range—a unique aspect that means it can be seen for miles to the south. The calcareous slopes of these southern extremities of the Jura Mountains offer an excellent environment for grape growing. This combines with the sunny aspect and good natural drainage of the landscape. The steep slopes of the Manicle Cru vineyards optimize sunshine exposure during the growing season. High altitude Pinot Noir sports fresh red fruit and seductive tannins; featured flavors are rose, raspberry, sour cherry, anise and paprika.

6 Blard & Fils ‘Pierre Emile’, 2020 Vin de Savoie ‘Pinot Noir’ ($32) RED

6 Blard & Fils ‘Pierre Emile’, 2020 Vin de Savoie ‘Pinot Noir’ ($32) RED

Considered by critics to be among the best examples of this varietal in Savoie, the wine shows gaminess behind its elegant cranberry mantle with hints of iron, forest floor, cassis, wild strawberry and violet. The acidity remains at the forefront and will be tamed with a bit more bottle time; the tans are elegant, silky and integrated.

AOPs Bugey and Bugey-Cerdon: The Sparkling Lightness of Being

Bugey, with its particular focus on sparkling wine, combines all the best grape-growing elements of mountainous eastern France. It’s found close to the border with western Switzerland and the city of Geneva and covers the southern limits of the Jura mountain range; the Rhône river loops around the southern end of Bugey before flowing south to the famous vineyards of the Rhône.

The majority of Bugey vineyards surround the town of Belley with another cluster farther north, somewhat contiguous with the vineyard area of the sparkling Bugey-Cerdon. While not technically connected under French wine law, Bugey is often grouped together with Savoie due to the both geographical proximity and the wine styles produced. As in Savoie, the best Bugey sites are on the south-facing slopes where the combination of cool subalpine air, sunshine and free draining limestone soils provides the best chance for the grapes to achieve optimal ripeness.

Chardonnay is the principal grape found in Bugey and must make up at least 70% of Bugey still white wines. Smaller portions of Aligoté, Altesse, Pinot Gris and Jacquère are permitted in the blend, and the sparkling wines may have larger portions of Jacquère and Mondeuse Blanche, known as Molette. Bugey reds are made from Gamay, Pinot Noir and Savoie’s characteristic Mondeuse. Rosé wine is usually made from Gamay and/or Pinot Noir.

Sparkling white Bugey is made mainly from Chardonnay, Jacquère and/or Molette, while the reds and rosés are principally Gamay and/or Pinot Noir.

Domaine Renardat-Fâche

Bugey-Cerdon

Like many of the best estates in France, Domaine Renardat-Fâche is a multi-generational concern that traces its roots back to the Second World War, Léon Renardat and his wife Cécile, with the help of a local winegrowers, began to produce Cerdon sparkling wine using the ancestral method—a technique that avoids added yeasts or sugars. In 1974, the couple’s son Alain returned to the estate after his studies in Beaune. In 1996 , Elie, Alain’s eldest son, joined his father in the company and continued to develop the family business. This included obtaining an Ecocert FR-BIO-01 organic farming certification in 2012.

Elie Renardat, Domaine Renardat-Fâche (Courtesy of Privacy Glass)

Located around the village of Mérignat in the foothills of the Jura massif between Lyon and Geneva, the vines are grown on clay/limestone soils, some of them dating back three of the family’s nine generations.

7 Domaine Renardat-Fâche, 2023 Bugey Cerdon ($28) SPARKLING ROSÉ

7 Domaine Renardat-Fâche, 2023 Bugey Cerdon ($28) SPARKLING ROSÉ

79% Gamay and 21% Poulsard from 32 organically-grown acres in high, rolling, wooded and steep hills of rocky clay-limestone soils. The fruit is harvested by hand, then gently pressed and naturally fermented at very cold temperatures in steel tanks. As is the standard in the ancestral method, the wine is bottled while fermentation is ongoing, producing the effervescence. 8% alcohol by volume.

Setting the IGP (Country Wine) Stage: Vin des Allobroges

IGP (Indication Géographique Protégée) is the European Union-wide name the category once called Vin de Pays, the ‘country wines’ of old. Certain wines from parts of the Savoie and Haute-Savoie region are not entitled to be labeled under the AOP name even if they hail from the same boundaries as Vin de Savoie, Roussette de Savoie or Seyssel. This category focuses on geographical origin rather than style and tradition, and gives winemakers greater stylistic freedom than AOP rules.

Domaine des Ardoisières

The Valley of Tarentaise

Tarentaise vineyards pride themselves as being the first ones in France (if you’re coming from Italy); they sit slightly north of the 45th parallel and occupy the south-facing slopes of the Tarentaise Valley, where soils are composed of schist and ardoise. The area is on the comeback trail, reflecting a self-sufficient agricultural society that started to decline around 60 years ago, leaving behind much fallow land. From the 5000 or so vineyard acres that dotted the area during the first half of the 20th century, not many remain today, and those that do are maintained by a small number of diehard wine growers.

In 2005, Brice Ormont left the rolling hills of his native Champagne to make wine in the shadow of Mont Blanc. Domaine des Ardoisières was created in 1998 by the iconic grower Michel Grisard; Brice Ormont took over upon Grisard’s retirement. The vineyard was planted on slopes up to 60% in grade with local grape varieties like Jacquère, Mondeuse, Altesse, and Persan. So steep is the region that Ormont claims that it receives two hours less sunlight per day; an hour in the morning and another in the evening.

Brice Omont, Domaine des Ardoisières

“You’d think that ripening grapes would be a problem but this is not the case,” Ormont insists. “Seven of our acres face the rising sun in the east and seven more face the setting sun in the west, with the east-facing vineyards reaching incredibly high temperatures of up to 120°F during the day when the sun bounces off the schist rock and magnifies the temperature. During summer the working day stops at 1 p.m. as working these south-facing slopes in the afternoon is physically impossible.”

Gamay Noir à Jus Blanc: Mellifluous When Young, Profoundly Delicious with Age

Gamay is grown throughout Savoie and Bugey—it is the most widely planted red variety in the region, covering about 14% of the AOP vineyards. As an early budding grape, it presents yearly challenges to an alpine climate, however, and the success of the harvest in any given season depends not only on the weather, but on the age of the vines and the skill of the producer. It is a favored red in Chautagne, in whose terroir it expresses a profile of cinnamon, spices, raspberry, strawberry and pepper.

Domaine des Ardoisières ‘Argile’, 2019 IGP Vin des Allobroges ‘St-Pierre de Soucy’ ($45) RED

Domaine des Ardoisières ‘Argile’, 2019 IGP Vin des Allobroges ‘St-Pierre de Soucy’ ($45) RED

A blend of 80% Gamay and 20% Persan from 40-year-old vines grown on slate in Saint-Pierre-de-Soucy, ‘Argile Rouge’ is the rare wine that manages to present both delicacy and saturation at the same time. The nose is slightly smoky, with a touch of white pepper and red bramble; the fruit notes become more pronounced on the palate, which is bright with red currant and pomegranate. The true minerality of the mountain terroir shows up at the finish.

Persan: The Renaissance It Deserves

Persan is the poster-child grape for a wonderful variety that fell out of favor with growers, due in part to its susceptibility to fungal disease in damp weather. Among those in the know, who are willing to work with this fault, it is highly prized. Persan seems to have originated in the Maurienne Valley and was presumed extinct until it was rediscovered being grown by some local Savoie viticulturists who use it primarily as a blending grape. Alone, it produces age-worthy reds with a strong aromatic profile and in assemblages, this is what it brings to the table..

Domaine des Ardoisières ‘Améthyste’, 2018 IGP Vin des Allobroges ‘Cevins’ ($99) RED

Domaine des Ardoisières ‘Améthyste’, 2018 IGP Vin des Allobroges ‘Cevins’ ($99) RED

Biodynamically-grown Persan (60%) and Mondeuse Noire (40%) from the steep monopole Cevins with full southern exposure and a terroir of schist and mica. Yields are restricted to an average of only 20hl/ha, following which the grapes were whole-bunch fermented on native yeasts before spending 18 months in neutral oak. The flavor profile may be likened to a Côte-Rôtie with some of heavy notes replaced by the airy freshness of mountain wine; stone, raspberry and a touch of pepper to balance the bright salinity of the finish.

Notebook …

Climate Change: Peril and Possibility

“There is nothing constant but change.” Heraclitus, 500 BCE

It’s not likely that the Greek philosopher had Savoie wine industry in mind when he made his prophetic statement, but even in his time, viticulture depended almost entirely on the weather. And even then (and in every vintage since), the climate has been subject to gradual shifts, some more dramatic than others. Thomas Jefferson, who lived during the Mini-Ice Age of the eighteenth century was unable to grow vinifera grapes in his famed Monticello vineyards. Today, they thrive there.

In Savoie, where the threat of freezing temperatures early in the season and harsh storms in the fall haunts every vintage, there are some obvious upsides to warmer springs, hotter, drier summers and more temperate falls across the region.

But it’s a double-edged sword, since along with the extra balm comes unpredictable hailstorms, and although spring frosts may lessen on the whole, those that do hit seem to redouble in intensity. It doesn’t take more than a couple of these before a vineyard cannot recover. This doesn’t even touch on the potential threat to the ski industry, one of Savoie’s biggest draws and a steady source for wine customers.

Winemakers in Savoie feel somewhat helpless in the face of the climate—a plight of the profession since the days of Heraclitus. Innovation, which has saved the day throughout history, will find a way. In Savoie, a new generation is focused on sustainability and it is a start, but the hard truth is that marginal appellations Like Savoie are having to adapt and modify systems and farming practices that have been in place for centuries.

- - -

Posted on 2025.09.12 in Savoie, Arbois, France, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

Qué Será, Syrah: How One Grape Speaks the Vernacular of Five Northern Rhône Appellations, Through Ten Producers.

The triumvirate of Côte-Rôtie, Cornas and Hermitage rule the narrow terraces of Northern Rhône indomitably and are responsible for the world’s best Syrahs. They’ve been called ‘unicorn wines’ in that the best of them are rare, and if available, very expensive.

Throw the slightly more affordable Saint-Joseph and Crozes-Hermiatge into the fray, and you have a quintet of Syrah superlatives—the global benchmark for this richly expressive varietal on which the fortunes of Northern Rhône have been made … and lost.

Northern Rhône: Etched into the Mountain

The vineyards of Northern Rhône may be the oldest in France, but one thing is certain: Harvesting them ages the workforce. The terraced hillside sites are so steep that the grapes sometimes have to be lowered by pulley, like on a ski slope. It’s said that, in order to make a commercially viable product on sites with sufficient sunlight to fully ripen grapes, you have either to inherit an established right-bank vineyard or produce a wine so good that you can charge an exorbitant price.

Indeed, the most famous producers of the Northern Rhône are family enterprises; these are wineries that vinify grapes they grow, but also purchase fruit from vineyards along length of the entire Rhône valley. The smallholders are the ones who put the sweat equity into these demanding sites, and traditionally, only a handful of them have bottled under their own labels.

This is beginning to change as ambitious newcomers have entered the foray as grower/producers and, at least among those who have been up to the test, have improved the overall quality of the appellation.

Northern Rhône Wines: Syrah’s Reign Over the Unyielding Slopes

In the Rhône, Syrah is such an aristocratic grape that it has its own disease: ‘Syrah Decline’ reared its ugly head in 1993, and causes vines to wither and sometimes die; its cause remains unknown.

On a more salubrious note—and equally interesting—much of the top Rhône wines you may consider 100% Syrah are actually made from a clone called Sérine, most being massale-selections from field cuttings. Sérine is not identical to Syrah, in the field or on the palate; it’s more than likely a mutated and evolved version that seems restricted to Northern Rhône. It is also more savory than many contemporary Syrahs, and it is this quality which has induced winemakers to highlight this quality above all. Côte-Rôtie has traditionally blended a portion of Viognier into their Syrah-based reds to impart floral overtones that may not match this popular swing toward meatier Northern Rhônes.

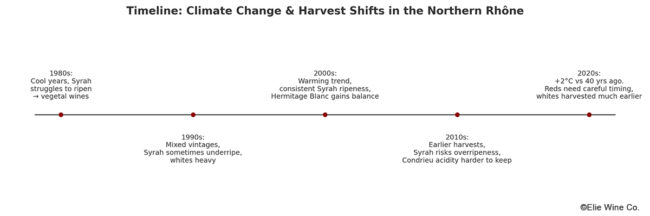

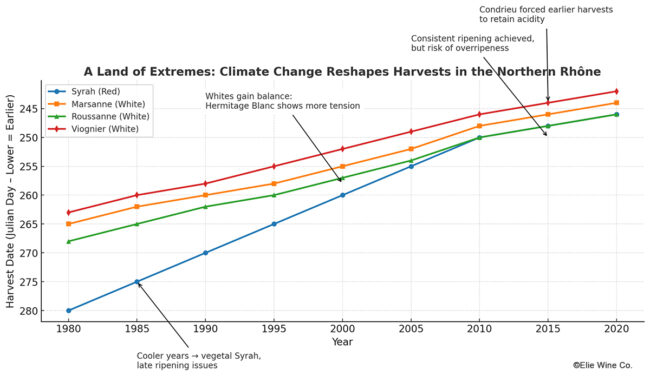

A Land of Extremes: Climate Change Reshapes Syrah’s Harvests in France’s Steepest Vineyards

The terraced vineyards on the cliffs overlooking the Rhône River have always challenged wine growers on multiple fronts. The free-draining soils makes adequate rainfall a must and the Mistral winds exacerbate drought during dry spells by stripping moisture from the vines, forcing growers to plant cover crops to retain soil moisture; others experiment with mulching or adjusting canopy height to shield grapes from sunburn.

Add to that the issue of ripening Syrah at high altitudes: In years without adequate sunshine, grapes failed to reach phenolic ripeness by harvest times that are inherently limited by mountainous weather conditions. As a result, during off years, the wines of Northern Rhône tend to be vegetal, with distinct hard edges.

Enter climate change, bringing with it both heightened aggravations and surprising consolations. Over the past 40 years, average temperatures have risen by more than 2°C in the region—so much that Syrah now generally ripens without fail. Harvests must be timed carefully to avoid overripe grapes, which produce flabby wines without Northern Rhône’s customary taut acidity and pepper edge.

Another consequence of climate change is the improvement it has brought to white wines. Marsanne, Roussanne and Viognier welcome extra warmth, become riper earlier, before their critical acids begins to dissipate. Hermitage Blanc in particular, once heavy in cool years, now shows electric tension alongside richness, while Condrieu, which once had a tendency to get too ripe, is forcing growers to pull forward harvests earlier.

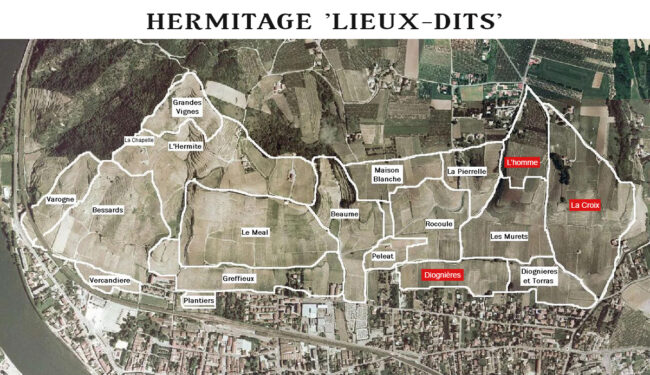

Northern Rhône Lieux-dits: Terroir Distilled to Its Smallest Scale

Lieux-dits are a wine lover’s Google Earth; a satellite view of an appellation focused on a tiny, representative parcel. Not all vineyards have lieux-dits, and among those that do, not all are created equal. In general, it’s a term that refers to a geologically homogenous portion of a vineyard with a self-contained story to tell about its quality or, occasionally, its significance to history. Although lieux-dits are generally not required to be formally registered, they are always named, and that name may occasionally be confused with a producer’s cuvée name, which is often similar. Different appellations have different laws regarding lieux-dits; in Alsace, for example, they are mandatory for Grand Cru AOP labels, whereas in Burgundy, Grand Crus are forbidden from using them.

In the Rhône, lieux-dits are often associated with the region’s top estates, and those that do not have an officially registered place in the French Cadastre are considered ‘les marques’ of their producers. In either case, they are ‘terroir distilled’—an extremely fine-tuned expression of an individual location. To recognize one is to recognize that within the sprawling Rhône there exists an almost microscopic essence that only a lieu-dit can reveal.

Hermitage: Syrah in Its Grandest

Hermitage, one of France’s most reliable appellations, is a pipsqueak that carries a big stick—both its reds and white wines are long-lived and full-bodied. The 345 acres of vineyards entitled to wear the name ‘Hermitage’ are located on a granite hillside facing south and overlooking a short section where the river Rhône flows west to east rather than north to south.

This orientation means that the grapes benefit from the maximum amount of sunlight throughout the day.

Due to slope erosion, Hermitage topsoil is relatively thin compared to that on the valley floor. However light, there are a wide variety of soil types, ranging from sandy gravel in the west, to rockier areas higher up and limestone in the center. As intense Rhône sunshine warms the hillside during the day, the granite bedrock stores this heat, encouraging the grapes to ripen more fully than those in less-exposed sites.

The effect of the local terroir is most pronounced on the western side of the hill where it is steeper than the east and enjoys prolonged exposure to afternoon sunshine.

Jean-François Jacouton

The Hand of the Revivalist

Many vignerons tout their studies abroad, but Jean-François Jacouton is proud to champion his apprenticeship at Domaine Courbis at the southern tip of Saint-Joseph.

“Still,” he maintains, “It was my experiences in Savoie that taught me the value of brining mineral freshness to the wine.”

In 2003, Jacouton took over his grandfather’s acres in a few miles north of Tournon, a city that backs into the hills surrounding the Rhône Valley. In 2010, he began domain bottling. His Saint Joseph holdings include older vines in lieux-dits Les Goutelles, Verset Est Paradis, and Tinal, responsible for the stunningly rich Saint Joseph Rouge labeled Pierres d’Iserand.

Jean-François Jacouton

Dedicated to lutte raisonnée farming using horses and hand plowing, Jean-François spends spending almost all of his time among the vines.

“We are in process of reconstructing old stone terraces in areas that returned to forest following phylloxera,” he says. “This commitment to the land is the hallmark of my approach. I strive for classic, old-school reds, but emphasize cleanliness and precision. This is achieved through careful selection in the vineyards, and in the cellar, vinification and aging are in cement, amphora, demi-muids, and larger foudres fermented parcel by parcel and by using an overage of only 20% new wood.”

Jean-François Jacouton, 2021 Hermitage ($82)

Jean-François Jacouton, 2021 Hermitage ($82)

100% Syrah grown on limestone sand and clay from older vines in the lieux-dits Diognières, L’homme and La Croix. The harvest is entirely destemmed with pigéage and pump-overs for 27 days followed by aging in French oak barrels for 14 months. The wine shows classic aromas of graphite, bacon fat, roasted spice and blackberry, all wrapped in a brilliant minerality.

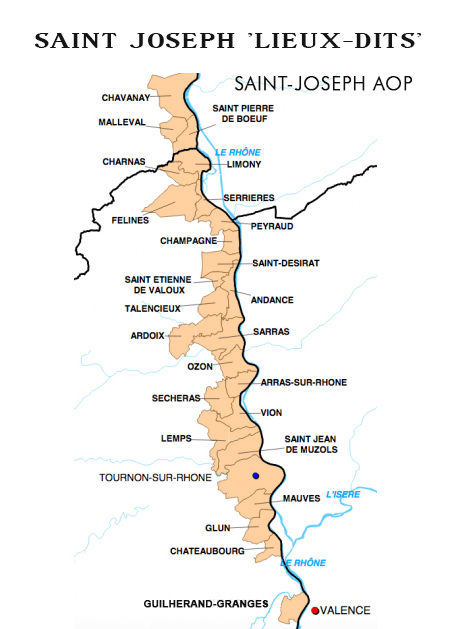

Saint-Joseph: Syrah Finds Its Middle Voice

Unlike Hermitage, St-Joseph covers a lot of territory and multiple terroirs; it encompasses 26 communes and stretches from Chavanay in the north to Chateaubourg in the south, roughly 30 miles in length. The reds from the region can be light for Rhônes, a result of soils containing less granite and vines that face east rather than south. But in strong vintages, they are spectacular.

80% of the wines made in Saint-Joseph are Syrah; only a minuscule quantity—a tenth of one percent—contain any other red wine grape. White wines makes up two in ten bottles of Saint-Joseph’s production and are based on Marsanne and Roussanne, blended or as stand-alones. These wines are dry, with honeyed, floral aromas and balanced weight and acidity, in marked contrast to the sweet Muscat de Beaumes-de-Venise wines from the southern Rhône and the heavier Viognier-based wines of Condrieu and Chateau-Grillet.

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Pierres d’Iserand’, 2020 Saint-Joseph ($35)

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Pierres d’Iserand’, 2020 Saint-Joseph ($35)

100% Syrah from old vines in the lieux-dits Les Goutelles (at a thousand feet elevation), Verset Est Paradis (at 600 feet), and Tinal (at 1200 feet). The grapes are 30-40% whole-cluster fermented with pigéage for 24 days and aged in demi-muids for 15 months. The wine offers a nice balance of fruit and spice, with plum notes alongside dried thyme and wild raspberry; on the mid-palate, you’ll taste smoked meat and olive tapenade, all complemented by refreshing acidity.

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Chemin de Sainte-Épine’, 2019 Saint-Joseph ($46)

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Chemin de Sainte-Épine’, 2019 Saint-Joseph ($46)

100% Syrah from old vines in the historic lieu-dit of Sainte-Épine, perched above the village of Saint-Jean-de-Muzols. Vinification is 30% whole clusters for 24 days, with pigéage and rémontage, followed by aging in new and used oak barrel 16 months. Structured and taut, the wine is loaded with concentrated flavors of wild berries and plum compote with subtle toasted notes and silky tannins.

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Chemin de Sainte-Épine’, 2019 Saint-Joseph ($99) 1.5 Liter

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Chemin de Sainte-Épine’, 2019 Saint-Joseph ($99) 1.5 Liter

The larger format of this wine from 2019 is ideal for cellar storage, which slows and mellow the aging process, likely for many years.

Domaine Jolivet

The Saint-Joseph Upstart

‘St. Joe’—with its rolling granite hills on the west side of the Rhône River—is an amazing discovery. It offers the best of Rhône hillside fruit, vinified by masters of the vine working outside the pressure of the spotlight, for a fraction of the price of the more famous estates in Côte-Rôtie and Hermitage.

Among the young vignerons who are making a vinous mark in the region is Bastien Jolivet, who tends working his family’s vineyards in the hamlet of Saint-Jean-de-Muzols, just north of the birthplace of the appellation in Mauves. When Bastian returned from various internships locally and abroad (Domaine du Monteillet in Condrieu and further afield in New Zealand and South Africa), he convinced his parents to stop selling the fruit from their 26-acre vineyard to the local cooperative and bottle their own wine. This was 2014; since then, Domaine Jolivet in general—and Bastien in particular—have hauled in considerable praise, culminating in Paris with the award Grand Prix Discovery of the Year 2020 by La Revue du Vin de France for best new winemaker.

Bastien Jolivet, Domaine Jolivet

As always, the land represents the soul of the passion. Bastien says, “My goal is to work towards a complete organic certification, and in the meantime, most of our field work is handled organically. The steepest grades, of course, are the hardest to assure pure organic cultivation. All of our little plots run up the hill of Saint-Jean-de-Muzols, which often makes hand-picking a necessity. In the cellar, all fermentations are done spontaneously and aging is done in combination of 228-liter barrels and 600-liter demi-muids, nearly all used. The assemblage is done just before bottling with some time for the wines to knit together. The wines are not fined and only filtered minimally with SO2 kept to a minimum.”

2018 Domaine Jolivet ‘Cuvée 1907’, 2018 Saint-Joseph ($70)

2018 Domaine Jolivet ‘Cuvée 1907’, 2018 Saint-Joseph ($70)

Named after the year in which the vines were planted, it is unlikely that you can find a more intense wine from any Rhône vineyard as old and at such a reasonable price: This is required sipping for anyone curious as to the sort of wine super-old Syrah can produce. The grapes are 100% whole-cluster fermented in stainless steel, then aged in ten-year-old demi-muids to best reflect the concentration of the fruit. It shows dark bramble berries, white pepper and blood orange zest.

Matthieu Barret

(Domaine du Coulet)

The Playful Radical

Matthieu Barret had an interesting plan when he took over Domaine du Coulet: To create a playful range of wines using serious technique. The success of the adventure can be gauged by how coveted his wines are, considered among the most accessible natural wines in France.

A 7th generation vigneron, Matthieu farms the vineyards that grandfather planted after WWII, intending to sell to some of the best-known producers in the Northern Rhône, including Chapoutier and Delas. In 1998, at the age of 23, Matthieu took over the family’s 25 acre vineyard in Cornas.

Matthieu Barret, Domaine du Coulet

Of his philosophy, he says, “I have always believed that the vine is happier in a wild environment. So, we have created ‘green spaces’ around the farm, digging watering holes to nourish a diverse ecosystem of vines, forest, meadow, and woodland. To further this way of thinking, I no longer use machines, replacing them with mules, horses and manual labor. Also, in a pursuit of purity and expression, I radically changed the customary vinification process by utilizing concrete eggs rather than oak.”

Currently, Matthieu creates an array of wines from leased organic and biodynamic vineyards throughout Rhône, and through trial and error, found the formula to express the unique nuances of each micro-terroir. He believes that his portfolio not only expresses the spirit of the land, but his own.

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘D86’, 2020 Saint-Joseph ‘natural’ ($48)

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘D86’, 2020 Saint-Joseph ‘natural’ ($48)

A punchy and classically-lined Saint-Joseph, farmed biodynamically and vinified with whole-cluster fermentation and aging in a mix of 10 hectoliter terracotta pots and concrete vats. The wine is bottled unfiltered, with minimal sulfur additions. It displays wild blueberry and blackcurrant notes shored with up subtle spices and a touch of licorice.

Crozes-Hermitage: Syrah in Its Most Approachable Expression

Crozes-Hermitage is the largest of the Northern Rhône appellations, but it labors in the shadow of its storied namesake Hermitage without pretentions of equality. Price reflects that, of course, and the wine itself does hold at least some measure of the magnificence found in its massively rich, long-lived neighbor. The wine-growing region has a continental climate distinct from the Southern Rhône, and its sheer size adds to the diversity of its terroir. Soils south and southwest toward Gerans largely consisting of granite and clay, while Tain-l’Hermitage is primarily made up of rocks, sand, and clay. The flatter topography in the southern Crozes-Hermitage area is primarily alluvial soil due to Rhône river deposits.

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘Et La Banière…’ , 2021 Crozes-Hermitage ‘natural’ ($40)

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘Et La Banière…’ , 2021 Crozes-Hermitage ‘natural’ ($40)

Et La Banière originates on the well-drained clay/limestone in Les Croix. In line with his biodynamic philosophy, Matthieu Barret pampers each Syrah vines organically and carefully controls yields. Maceration and fermentation is done on indigenous yeasts with pump-overs pumping concrete vats. The wine shows dried cranberry, pie spices and melting tannins that will become more silken with age. Some tasters have suggested a slight fizz to this wine, which is likely the result of the natural process which eschews the use of sulfur.

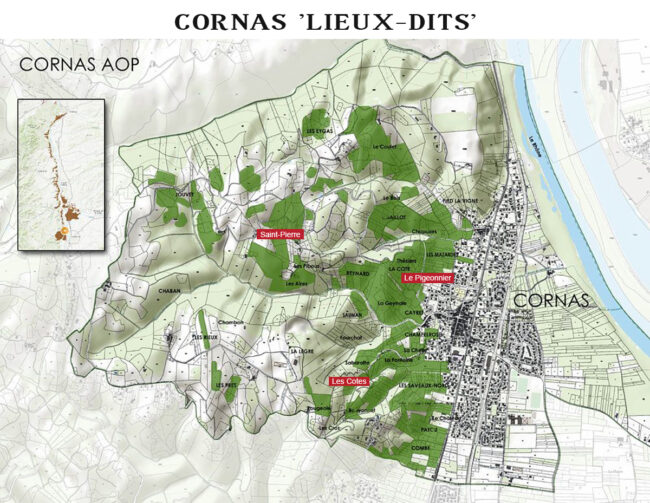

Cornas: Syrah Unbound

At just under three hundred acres, Cornas is even smaller than Hermitage; it’s smaller than some single estates in Bordeaux. It produces only red wines made exclusively from Syrah—a variety that ripens more easily here than nearly anywhere else in Northern Rhône. Celtic for ‘burnt earth,’ Cornas wines—in homage to the name or vice versa—often showcase smoky notes with deep, earthy tones. Once considered ‘country wines’ of value only to those who favor rusticity, the reputation of Cornas has surged in recent vintages, making it one of the most sought-after wines in France.

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘Brise Cailloux’, 2020 Cornas ‘natural’ ($89)

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘Brise Cailloux’, 2020 Cornas ‘natural’ ($89)

Brise Cailloux—the ‘Broken Stone’—comes from 50 individual micro-parcels. It spends it first year 50% used oak barrel and 50% concrete eggs, then is moved to concrete eggs for the second year. The wine lusty, yet gentle, with notes that are as complimentary as they are contradictory: Blackberry, violet, lavender, raw meat and blueberry. Accessible now, but with obvious cellaring potential.

Domaine Johann Michel

A Natural-Born, Self-Taught Vigneron

Give a man a bottle and he’ll drink for a day; teach him to make wine and he’ll drink for a lifetime. Still, there is something in the spirit of the man who figures it all out for himself that excites us even more.

Johann Michel developed a passion for fine wine while tasting old vintages with his grandfather, and from there, taught himself the art of vinification. Today, with his wife Emmanuelle, he works 14 acres spread between three Rhône AOP’s. This includes a scant acre in Saint-Joseph planted entirely to Syrah, two-and-a-half acres in the extreme south of Saint-Péray planted to Marsanne and Roussanne, and his most celebrated wines made from lieux-dits in the steep, granite infused slopes of Cornas.

Johann Michel

Michel may be self-taught, but the effusive praise for his product is very much the domain of experts. In what may be the most hyperbolic wine review I’ve ever read, critic Jeb Dunnuck (Northern Rhône: 2019s From Bottle, February 16th 2022) wrote: “The Cornas from Johann Michel is a majestic, full-bodied, incredibly seamless beauty that does everything right, showing the ripe, sunny style of the vintage and bringing ample fruit, richness and power with incredible focus as well as purity and freshness. It will evolve for 15 years or more, and I doubt it will ever close down. Those who like flawlessly balanced Cornas should back up the truck for this sensational wine.”

Domaine Johann Michel ‘Cuvée Mère Michel’, 2020 Cornas ‘Les Côtes’ ($149)

Domaine Johann Michel ‘Cuvée Mère Michel’, 2020 Cornas ‘Les Côtes’ ($149)