Bloomsday Commemoration (June 16) – Jurassic Odyssey: Chablis Elevates Terroir to Its Most Precise Expression. Exploring Grand Crus and Premier Crus Over Three Vintages, in Three Sampling Packages.

2024 marks the hundred-and-second anniversary of the release of James Joyce’s modernist masterpiece ‘Ulysses,’ and a few venerable souls who purchased a copy on the day it came out are still trying to wade through it. Not everyone agrees on the genius of the work—a florid, stream-of-consciousness ramble through Ireland’s capital city over the course of a single day (June 16, 1904) featuring Leopold Bloom, his wife Molly and would-be-writer Stephen Daedalus—but everyone can appreciate the remarkable image Joyce painted of Dublin at the turn of the century; the people, the streets, the offices, the brothels and above all, Davy Byrne’s pub:

“Nice wine it is. Taste it better because I’m not thirsty …. Mild fire of wine kindled his veins. I wanted that badly …. Glowing wine on his palate lingered swallowed. Crushing in the winepress grapes of Burgundy. Sun’s heat it is.”

June 16 is known as ‘Bloomsday’ and is commemorated by Joyce fans across the globe. At Elie’s, we prefer to take our own literary license and use the occasion to celebrate Bloom’s passion, ‘the winepress grapes of Burgundy’ with our own amble through Burgundy’s unparalleled countryside.

Chablis: Burgundy’s Golden Gate

James Joyce appreciated France (he studied at the Sainte-Geneviève Library) and France appreciated him back—‘Ulysses’ was first published at Sylvia Beach’s Paris bookstore, Shakespeare and Company and printed in Dijon by Maurice Darantieres.

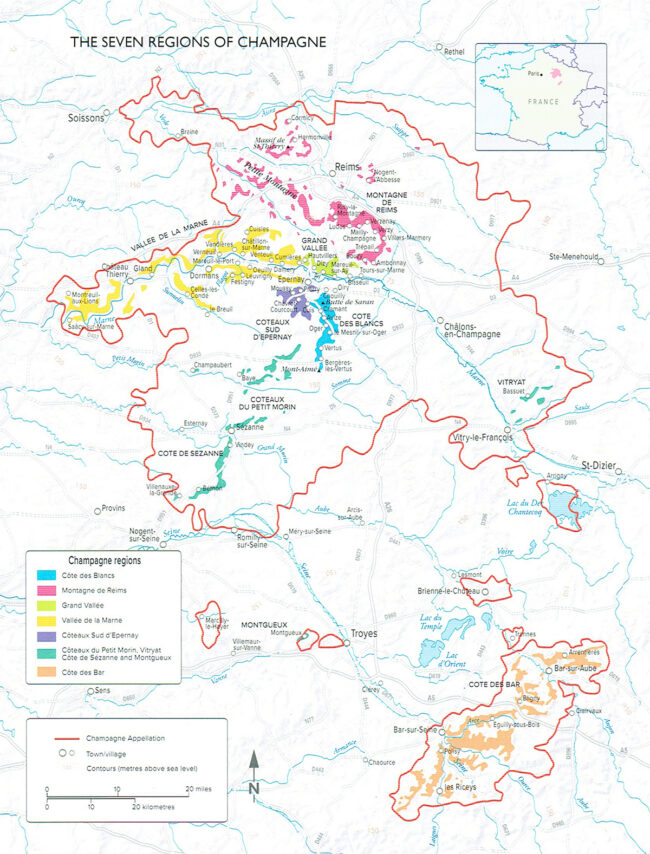

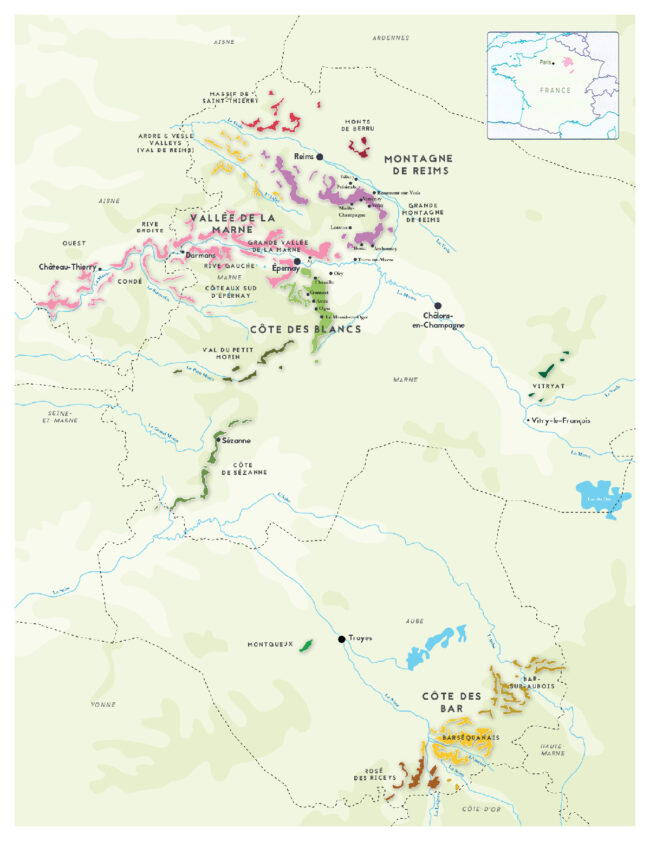

A hundred miles below the 6th Arrondissement (the location of the bookstore) and about the same north of Dijon, the valleys and wooded hilltops of Chablis begin, with vineyards festooning the slopes that run alongside the pretty River Serein—aptly translated to ‘the serene river.’ Spanning approximately 10,000 acres and encompassing 27 communes, there are 47 vineyards classified as Premier Crus and seven Grand Crus.

In terms of terroir fanaticism, Chablis is first among equals in France. The key divide in quality levels lies between vineyards planted on Kimmeridgian soils and those with Portlandian soils. Kimmeridgian is more highly regarded; it contains greater levels of mineral-rich clay, as well as the essential marine fossils which are responsible for its significant lime content. Kimmeridgian soils are the source of the trademark ‘goût de pierre à fusil’, or gunflint, which can be preserved in the best wines for decades.

The wines of Chablis, at whatever level (Chablis Grand Cru, Chablis Premier Cru, Chablis and Petit Chablis) are Chardonnay and nothing but; all but the most heralded are vinified and aged without oak, giving them the greenish gold hue that exemplifies the appellation as well as the classic minerality of the nose.

Elaborating Chardonnay: Back to The Origins

All Chablis is Chardonnay, but not all Chardonnay is Chablis. That deceptively simple fact belies the multiple faces that this variety adopts in the relatively small confines of Burgundy—incarnations based equally on terroir and tradition. The Côte Chalonnaise and Mâconnais tend to produce balanced, approachable, subtly-oaked Chardonnays that Americans may know best from the 1990s craze of wines from the village of Pouilly-Fuissé.

The Côte d’Or, on the other hand, turbo-charges the concept by producing oaky, complex and long-lived wine. Only the most intensely-flavored fruit can stand up to this style of oak-barrel maturation, but the resulting wines are at the pinnacle of the world’s great whites.

The third style features in this week’s packages, where a cooler climate and northerly latitude barely allows the grapes to ripen, thus ensuring that Chablis makes a leaner style with higher acidity that does not lend itself to intensive oak-aging. As such, these wines are pristine, rarely seeing new oak at all, and only occasionally seeing milder, seasoned barrels to soften some of the electricity.

Chardonnay in Chablis: Acid Trip

Acidity in wine must be handled with the same circumspection as in the laboratory—make a wrong move and you end up with a wincing sting; in either case, it’s a fail. Balance is the key in all things wine, but clearly, wines from more northerly regions face a bigger struggle in balancing ripeness with sharpness, and Chardonnay is the poster-child varietal for ‘If life hands you lemons, make Chablis.’

The line between refreshing tension and acid-reflux may be fine, and one reason that aging Chablis has always been a requirement in Cru versions is that time softens acids and allows the briny, saline-driven savoriness to blossom. Nearly all Chablis undergoes a secondary malolactic fermentation prior to bottling, a technique that transforms malic acid into softer lactic acid and provides a more stable environment. Most Premier and Grand Cru Chablis also see time in neutral oak to further the mellowing process before facing the catwalk of consumption.

Jurassic Odyssey: What Lies Beneath

“The vineyards of Chablis have a single religion,” writes Jacques Fanet in his book ‘Les Terroirs du Vin’: “Kimmeridgian.”

Kimmeridgian limestone marl – courtesy of The Source

Soil in Chablis; big chunks of Portlandian limestone on top with soft Kimmeridian limestone marls underneath.

In the middle of the 18th century, a French geologist working in the south of England identified and named two distinct types of limestone from the Jurassic Era; Portlandian, which he found in Dorset with a layer of dark marl just below it, subsequently named after the nearby village of Kimmeridge. These strata also run across the Channel and through the north of France, where they become a part of the ‘Paris Basin’ and play an indispensable role in creating the soils. A slow geological tilting of this basin allowed the Seine, Aube, Yonne, and Loire rivers to cut through the rising ridges and form an archipelago of wine areas in Champagne, the Loire Valley and ultimately, Burgundy.

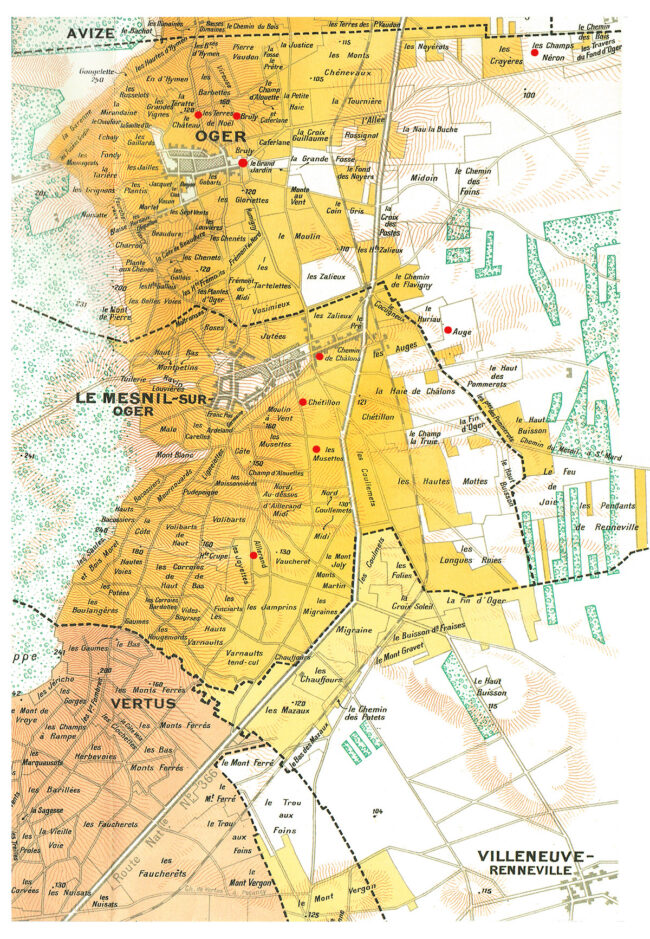

Chablis remains the biggest island in the Kimmeridgian chain and it is home to some of the finest Chardonnay terroirs found on earth. The defined region ‘Chablis’ was recognized in 1923 by the Wine Tribunals as requiring a sub-soil of Kimmeridgian limestone while wine grown anywhere else in Chablis would be classed Petit Chablis. The Grand Cru mid-slope in Chablis maps almost perfectly to the Kimmeridgian outcrop, with the soft, carbonate-rich mud rock capped by Portlandian Barrios limestone and supported by Calcares à Astarte, yet another type of limestone.

And now for the interesting part: As vital as Kimmeridgian soil is to the top Cru classifications in Chablis, it is not the primary consideration. Geologic conditions identical to those experienced by the Grand Cru slope extend both northeast and southwest, but the vineyards on those sites are classed as Premier Crus. As a matter of fact, the reference to Kimmeridgian limestone in the definition of Chablis was discontinued in 1976, a tacit admission that slope and orientation are of even greater importance to wine quality.

Rive-Droite vs. Rive-Gauche Premier Crus: Six-Bottle Package Sampler ($339)

When wine people become involved in right bank/left bank imbroglios, they’re usually arguing Bordeaux. Not today, where the banks are along a different river and within a different appellation and most assuredly showcase a different style: Chablis.

The River Serein runs through the Chablis valley, bisecting a series of Crus and Climats. As a quick refresher course, a Burgundian climat is a specific area that, due to superior physical and weather patterns, has been identified and named for producing wine with unique organoleptic qualities—appearance, aromas, taste and mouthfeel. ‘Climat’ is often used interchangeably with ‘lieu-dit,’ so for the record, here is the difference: A lieu-dit is a plot of land whose name refers to something precise in either historical or topographical terms; it is purely geographical and corresponds to a clearly defined area. A Climat can refer to a lieu-dit, to just a part of a lieu-dit, or even several lieux-dits grouped together. It is a statement of quality first, geography second.

Chablis, split down the spine by the Serein, contains 47 Climats that can be mentioned on the wine label; 40 of them produce Chablis Premier Cru and the remaining 7 make Chablis Grand Cru. The Chablis Grand Cru Climats are all found on the right bank of the River Serein, while Chablis Premier Cru Climats are found on both sides of the river, with 24 on the left bank and 16 on the right.

Decide for yourself in this week’s six-bottle package which of Louis Michel’s interpretations you prefer; we’ll offer a profile of each wine individually, of course, but as a general rule, wines from the left bank are more mineral and fresh while wines from the right bank are rounder and opulent.

The 2022 Vintage: Superb Harvest with Outstanding Lasting Potential

The worst reviews of Chablis 2022 call it ‘very good’, and from there, depending on producer, the sky is the limit. On top of being the sunniest summer on record, the preceding winter was mild and dry, with under five inches of precipitation over four months. Budbreak started at the end of March, and perhaps 30% were lost by a subsequent frost. But a second generation of buds proved productive, leading to good yields. June, July and August were hot and generally dry, though with enough rain to stave off drought. Maturity was early and quick, and harvest began toward the end of August and lasted into the second week of September.

Louis Michel & Fils

“Chablis des Amateurs”

Folks who say ‘yes’ to the magic of Chablis will appreciate the things to which winemakers Jean-Loup Michel and his partner/nephew Guillaume Gicqueau-Michel say ‘no’: Oak, bâtonnage and added yeast. Since 1970, fermentation has taken place entirely in stainless steel to preserve the essence of the Chardonnay grape—Michel & Fils is perhaps the best-known proponent of entirely oak-free wines, even in his three Grand Cru offerings. Bâtonnage—the stirring of the lees to make the wine fatter and richer—is atypical in Chablis, and at Michel & Fils, unheard of.

Guillaume Gicqueau-Michel

The Michel family has been a presence in Chablis since 1850. Situated in the heart of the village, the estate covers 60 acres that spread across over the very first slopes that were discovered by Cistercian monks in the 11th century and include three Grand Crus (Grenouilles, Les Clos, and Vaudésir), seven Premier Crus (Montmain, Forêts, Butteaux, Butteaux “Vieilles Vignes”, Vaillons, Séchets, Fourchaume and Montée de Tonnèrre).

The domain also produces village-level Chablis from twenty named communes and a Petit Chablis; offering wines from all four sub-appellations make Louis Michel a rarity among local producers.

Rive Droite Premier Crus

Not only is longevity is a hallmark of palate sensation in Chablis: more than half of the Climats entitled to wear the ‘Premier Cru’ label had their present-day names by 1429. Chablis Premier Cru represents about 14% of Chablis production, with sites scattered on either side of the Serein River and covering around 2000 acres. As in Bordeaux, where the location of the vineyard compared to the Dordogne and the Garonne determines the style and quality of the wine, the case is similar in Chablis. Again, as in Bordeaux, this is the result of soil, topography and exposure to the sun: On the right bank, close to the village, many of the well-known Premiers Crus share similar geology, exposition and characteristics with the Grand Crus.

Marc-Emmanuel Cyrot of Domaine Millet describes wine from the right bank this way: “The right bank provides complex, well-balanced wines, with a maximum of minerality and vivacity. These vines face south or southwest, getting warmer afternoon sun, making more opulent, fruit-driven wines, that can be steely and powerful.”

•1• Louis Michel & Fils, 2022 Chablis Premier Cru Vaulorent ($60)

•1• Louis Michel & Fils, 2022 Chablis Premier Cru Vaulorent ($60)

The Fourchaume vineyard, massive in both size and reputation, extends for nearly two miles … with the exception of one enclave which is found in the Grand Cru valley. Vaulorent comes from this enclave. The wine is fermented on native yeast in stainless steel tanks over at least 12 months with as little handling as possible, then bottled with slight fining.

The wine shows an arresting, gunflint-scented bouquet with focus and delineation that emphasizes shellfish, mineral reduction and floral, white-fleshed fruit flavors.

•2• Louis Michel & Fils, 2022 Chablis Premier Cru Montée de Tonnerre ($60)

•2• Louis Michel & Fils, 2022 Chablis Premier Cru Montée de Tonnerre ($60)

Set slightly back from the Grand Crus vineyards, Montée de Tonnèrre abuts Blanchot, where its moderate slopes, exposed to the west, welcome the sun in the afternoon. The grapes are protected from the east winds and ripen without much effort while the shallow soil, underlain with Kimmeridgean marly limestone, reveals veins of blue clay to gives the wines both minerality and energy.

The wine is intense and powerful, with nutty, honeyed accents, and in this outstanding vintage from an outstanding producer, it is every bit as good as many a Grand Cru.

Rive Gauche Premier Crus

There’s no genuine ‘left and right,’ of course: The so-called lefties lie on the Serein’s west side, where vineyards tend to face southeast and get morning sunlight. This results in lighter, more restrained wines with floral and green apple notes.

•3• Louis Michel & Fils, 2022 Chablis Premier Cru Vaillons ($54)

•3• Louis Michel & Fils, 2022 Chablis Premier Cru Vaillons ($54)

Vaillons is one of the largest Premier Cru vineyards in Chablis, sitting southwest of the town itself. As in all left bank climats, it gets an abundance of early sunlight to make fresh, slightly floral wines with intense minerality. The Climats Séchets and Les Lys can use Vaillons on their labels but often opt for their own names.

The lieux-dits of Chatains, Roncières, Mélinots—tiny parcels in the Valvan valley—are blended during vinification to produce aromas of toasted hazelnuts mingle with sweet white peach, soft spice notes and mild tobacco.

•4• 2022 Louis Michel & Fils Chablis, 2022 Premier Cru Montmains ($51)

•4• 2022 Louis Michel & Fils Chablis, 2022 Premier Cru Montmains ($51)

Montmains lies southeast of Vaillons, separated only by a small valley. It has particularly stony soils, making a lighter, leaner style of wine. Butteaux and Les Forêts lie within Montmains and are often seen on labels. Louis Michel’s four Montmain vineyards extend along a clay slope known for being sensitive to spring frosts, requiring extra care in the field.

The wine shows ripe, candied flavors with notes of saline behind spicy floral aromas, toasted almonds, candied lemon and apple and a lively, chalky finish.

•5• Louis Michel & Fils, 2022 Chablis Premier Cru Forêts ($60)

•5• Louis Michel & Fils, 2022 Chablis Premier Cru Forêts ($60)

Forêts is one of the three Climats included under the ‘flag-bearing’ Montmains, often overlooked. Typical of the left bank, Forêts’ south and east exposure provides exceptional sunlight, and the grapes can take all the time they need to ripen. Rather flat at the bottom, Forêts turns into a steep slope towards the top of the hill. Like many climats of Chablis, Forêts has a marly Kimmeridgian subsoil.

The wine displays classic gunflint along with earthier elements of fern and forest bracken mixed with ripe apricot, cocoa and pepper.

•6• Louis Michel & Fils, 2022 Chablis Premier Cru Butteaux ($54)

•6• Louis Michel & Fils, 2022 Chablis Premier Cru Butteaux ($54)

Proudly perched on a hilltop (or ‘butte’—hence, the name), Butteaux is a high-altitude climat that overlooks its neighbor Forêts. Butteaux south-facing slopes where too ventilation provides the grapes with the perfect terroir for easy ripening. In the subsoil, the Kimmeridgian marls are quite shallow and characterize in places by large blocks, while on the surface, white and blue clay with large stones facilitate drainage.

The wine originates in four parcels spread over the Butteaux slopes, the most distant acres from the Louis Michel winery. It shows caramelized baked-apple aromas with toasted nuts, wet stone made more complex by the earthy spice of forest undergrowth.

Right-Bank vs. Left-Bank Premier Crus Sampler: Two-Bottle Package ($145)

This is a winner-take-all package, two bottles, one each of right bank vs. left bank, both vying for palate supremacy.

The 2019 Vintage: Concentration and Complexity

A relatively mild winter, with few prolonged cold spells, got a bit antsy in the early spring with a couple of serious frosts, which cut into yields quite drastically. By the end of June, the temperatures reversed themselves in intensity and a long heat wave moved in. July was cooler, with August heating up again; overall the balance led to grapes in which acids concentrated along with sugars at the end of the season. The low-yielding 2019 vintage Chablis in Chablis produced wines that are simultaneously atypically concentrated but very incisive and structured, although aromatically, quite classically Chablisienne.

Domaine Billaud-Simon

Credit Napoléon’s loss at Waterloo for the establishment of Domaine Billaud-Simon; Charles Louis Noël Billaud returned home from the war to plant vines on the family holdings in Chablis. A century later, the estate expanded with the marriage of his descendent Jean Billaud to Renée Simon.

Winemaker Olivier Bailly, Domaine Billaud-Simon

Owned by Erwan Faiveley since 2014, the 42-acre site produces wine from four Grand Cru vineyards, including single-acre plots in Les Clos and Les Preuses. The Domaine also owns four Premier Cru vineyards, including Montée de Tonnèrre, Mont-de-Milieu, Fourchaume and Vaillons.

1 Domaine Billaud-Simon, 2019 Chablis Premier Cru Montée de Tonnerre ($81)

1 Domaine Billaud-Simon, 2019 Chablis Premier Cru Montée de Tonnerre ($81)

Montée de Tonnerre is a hundred acre umbrella vineyard sitting on a southwestern spur, with Blanchot and the Grand Cru sites just over the Bréchain valley to the north, and Mont de Milieu on the next hillside south. Billaud-Simon has plots within the three sectors of Montée de Tonnerre with the oldest plots in the Pied d’Aloup climat which are nearly 90 years old. Olivier Bailly normally only uses tank for this climat but this year has 6% in barrel.

The wine is mineral and intense, with nutty, honeyed characters beginning to emerge with age.

2 Domaine Billaud-Simon, 2019 Chablis Premier Cru Les Vaillons ($64)

2 Domaine Billaud-Simon, 2019 Chablis Premier Cru Les Vaillons ($64)

The 318 acre Vaillons vineyard is made up of eight, smaller climats, all Premier Crus in their own right, but also able to be blended together to produce, or just simply labeled Vaillons. Billaud-Simon’s Vaillons is a blend of six of them.

The wine shows electrifying acidity that has begun to mature with the sweet peach and green apple notes.

Left-Bank Premier Crus: Six-Bottle Sampler Package ($399)

This package focuses on the left bank alone (with one exception, L’Homme Mort), with all the unique site-specific glories contained within.

The 2020 Vintage: An Early Yet Classic Vintage

In 2020, the problem for Chablis was not reining in grape acid, but retaining it. Like much of Western Europe, Chablis experienced the warmest 12 months on record, warmer even than 2003. This meant an early start to the 2020 growing season and, while there were outbreaks of frost, the damage remained minor, particularly when compared to 2021.

According to Domaine Long-Depaquit’s Matthieu Mangenot, “2020 was a very easy vintage to manage. With a 40% reduction in rainfall and over 300 hours more sunshine than average, there were next to no disease issues in the vineyard. The dry weather even retarded weed outbreaks and this meant little to no spraying was required.”

One of the surprises that has emerged from persistent summer heatwaves brought about by a changing climate is a somewhat unique ability for Chardonnay to adapt without losing its sense of place. 2020 is a case in point, according to Mangenot: “Despite the heat and dryness, the alcohol levels are normal, the acidity levels are exceptional and the overall balance on the palate means the wines are representative of an excellent vintage for the region.”

Domaine Laroche

As one of Chablis’ most respected holders of Grand Cru vineyard land, Domaine Laroche is in many ways synonymous with the appellation. Shored up by a thousand years of history, the first Laroche to own land was Jean Victor who bought his first parcels of vines in the village of Maligny, a short distance from the village of Chablis. Passed along from father to son, the Laroche vineyards continued to expand gradually and by the mid-1960s totaled fifteen acres. In 1967, when Henri Laroche inherited this land, he had witnessed three years in the 1950s and 1960s in which there was no production at all; his vines yielded very little, and it was impossible to make a living from vine-growing alone—local farmers had turned to cereal crops and animal rearing to survive. Winemaking became something of a Chablisean afterthought, and so plagued was the region with spring frosts that Henri managed to save a section using rudimentary techniques such as burning straw and old tires.

Grégory Viennois, Domaine Laroche

With his son Michel joining the team, Laroche expanded into the best Crus in Chablis, for a current total of 222 acres, including 15 acres of Grand Crus, 52 acres of Premier Crus, and 156 acres of Chablis AOP. Only Chardonnay grapes are grown, of course, and the best vineyards are planted primarily on the region’s unique Kimmeridgian soil—a mixture of clay, chalk and fossilized oyster shells, renowned for producing crisp, mineral-driven, precise and elegant wines prized throughout the world.

•1• Domaine Laroche, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru L’Homme Mort ($82)

•1• Domaine Laroche, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru L’Homme Mort ($82)

L’Homme Mort is one of the most northerly Premier Crus in Chablis, located within the larger Fourchaume Premier Cru (Right Bank) just south of the town of Maligny. Wines made in this oddly-named (The Dead Man), 17-acre Climat share the softer, more rounded characters that are synonymous with Fourchaume while also possessing a distinctive zingy minerality.

The nose shows classic notes of minerals, citrus, brioche and stone fruits with a textured and balanced mouthfeel with saline tinges and bracing acidity.

•2• Domaine Laroche, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Beauroys ($69)

•2• Domaine Laroche, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Beauroys ($69)

Les Beauroys lies on the left bank of the Serein, and produces wines that are most often described as ‘charming’. It is among the earliest vineyards in Chablis to ripen and is known for being delightfully accessible in its youth.

The wine shows a delicate nose that combines anise with candied orange peel and leads to a pithy palate driven by citrus and salinity.

•3• Domaine Laroche, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Côte de Léchet ($72)

•3• Domaine Laroche, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Côte de Léchet ($72)

The Côte de Lechet vineyard lies just above the small village of Milly on the western side of the river. A southeasterly aspect gives it exposure to the less intense morning sun, in contrast to the more sunset-facing slopes on the other side of the valley. This encourages slower ripening in an already cool climate, and ensures that the acidity that typifies the region’s wines flourishes.

Elegant and floral with spicy undertones, the wine demonstrates a profound minerality that lingers through to the finish and adds complexity to the gentle acidity.

Domaine Long-Depaquit

Enviable Holdings

At more than 150 acres, Long-Depaquit is one of the largest domains in Chablis, renowned and respected not only for its sprawling terroir but for a commitment to low-intervention, organic farming. In 2014, upon completion of a new winery, the estate has focused on quality improvements centered on earth-friendly approach; in 2019, the property was awarded the highest Level 3 Haute Valeur Environmentale certification.

Beaune-based négociant Albert Bichot has managed Long-Depaquit since 1967, and the current winemaker, Matthieu Mangenot, joined in 2007 after dual training as an agronomist and an oenologist in South Africa, Lebanon, Bordeaux and especially, Mâconnais and Beaujolais. He has spearheaded the domain’s comprehensive approach to authenticity and sustainability.

Matthieu Mangenot, Domaine Long-Depaquit

Long-Depaquit produces around 180,000 bottles of Chablis each year, and like most large estates in the region, the lion’s share is village wine fermented and aged in 100% stainless-steel tanks. Wine from their six Premier Cru sites and six Grand Cru sites wines see a small percentage fermented and aged in barrels between two and five years old; Grand Cru Les Clos typically sees a higher percentage (25 to 35%) of oak.

Their flagship cuvée is Grand Cru La Moutonne, drawn from a 5.8 acre monopole vineyard that straddles two Grand Crus (95% in Vaudésir and 5% in Les Preuses) in a steep amphitheater capable of producing some of the richest, most complex wines in Chablis.

•4• Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Lys ($64)

•4• Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Lys ($64)

Les Lys is a Premier Cru climat within the larger, umbrella Premier Cru vineyard of Vaillons. While contiguous with the latter, Les Lys has a unique aspect, bordering Séchets but facing northeast over the town of Chablis towards the Chablis Grand Cru vineyards; the rest of the Vaillons climats face generally southeast.

A textbook example of how brightly Premier Cru Chablis can shine; grilled pineapple and yellow apple on the nose with a palate of salt-preserved lemon, crushed hazelnut and fruitcake spices.

•5• Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Vaillons ($55)

•5• Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Vaillons ($55)

Found in a valley to the southwest of Chablis on the western side of the Serein River, a southeasterly face and high-quality Kimmeridgian soils below meld to make this large climat a sought-after location. At 318 acres, the Vaillons vineyard is made up of eight, smaller Climats, all Premier Crus in their own right, one is Les Vaillons.

Tensile and incisive, the wine displays classic aromas of crisp green apple, citrus zest, white flowers and oyster shell with racy acids and loads of depth at the core.

•6• Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Beugnons ($59)

•6• Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Beugnons ($59)

Les Beugnons is located at the western extremity of the Valvan valley on the left bank of the Serein River, where the favorable exposure is very favorable for creating expressive and charming wines.

The wine shows rich aromatics of pear peel, slight smoke, yeasty lees and candied lemon following through with a juicy palate reminisicent of ripe Mirabelle and a touch of honey.

Keeping Potential: The Grand Crus – Six-Bottle Sampler Package ($724)

In Chablis, the Grand Cru appellation comprises seven climats—Blanchot, Bougros, Les Clos, Grenouilles, Preuses, Valmur and Vaudésir. It is mainly produced in the village of Chablis, but also at Fyé and Poinchy. At elevations between around 300 to 800 feet, and exclusively on the right bank of the Serein, Grand Cru vineyards enjoy the ideal combination of sunshine, exposure and soil, formed in the Upper Jurassic era, 150 million years ago, are composed of limestone and marl with Exogyra virgula, tiny oyster fossils.

The jewel in the crown of Chablis, this is a wine for keeping, for 10 to 15 years, sometimes more. One the nose, the mineral aromas of flint are intense, giving way to linden, nuts, a hint of honey and almond. In an ideal vintage, the balance is perfect between liveliness and body, encapsulating the charm of an inimitable and authentic wine.

1 Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Bougros ($108)

1 Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Bougros ($108)

Bougros is located at the northwestern edge of the Grand Cru hillside; it covers nearly 39 acres of slop on the Right Bank of the Serein and tends to produce wines that are rounded and less austere in youth than those from the other Grand Cru climats.

Silky and expressive, the wine offers brioche, toast and ripe green apple with petrol, dried peach and shellfish nuances.

2 Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Preuses ($117)

2 Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Preuses ($117)

The 29-acre Preuses slopes continue from those of the Bougros climat at the bottom of the hill, becoming increasingly steep toward the top. At the northern end of the Grand Cru slope, the Kimmeridgian soils and a sunny aspect make for an excellent terroir, but the wines tend to be rich and elegant, if less aromatic than other Chablis Grand Cru wines.

The wine is steely and rich with a gunflint character behind softer floral tones and hazelnut notes.

3 Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Vaudésirs ($135)

3 Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Vaudésirs ($135)

At the heart of the Grand Cru area, the Vallée des Vaudésirs is a perfect example of the geology and history of Chablis, bearing witness to the erosion that followed the last ice age. Long-Depaquit’s vineyard is more than forty years old, planted in the ‘endroit des Vaudésirs’, where, beneath steady sunshine, Kimmeridgian outcrops are the most numerous.

The wine’s bouquet is redolent of citrus fruit and delicate lily and chamomile notes while the palate offers green apple notes, hint of white peach and a hint of coastal herbs.

4 Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Clos ($135)

4 Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Clos ($135)

At 65 acres, Les Clos is by far the biggest Grand Cru climat in Chablis. Its southwest exposure, offering perfect sun, combines with a relatively steep slope to provide optimal ripening conditions. Because of its size, Les Clos’ soil is multi-faceted: towards the top, stones and limestone become more prevalent, whereas towards the bottom, on the contrary, it gets deeper with more clay.

The wine blends two plots and reflects the specificity—the bouquet combines floral notes from the higher of the two plots with almond and hazelnut notes from the mid-slope vineyard.

5 Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Blanchots ($117)

5 Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Blanchots ($117)

Blanchots provides a unique soil composition, combining typical Chablis Kimmeridgian limestone with ammonites and a layer of white clay. Blanchots takes its name from this white clay, which retains moisture and protects the vines from hydric stress.

The wine shows a floral nose dominated by lilies and white roses; the ample mouth is generous with citrus and stone fruit, leading to mineral fish with hints of flint and graphite.

6 Louis Michel & Fils, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Grenouilles ($112)

6 Louis Michel & Fils, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Grenouilles ($112)

At under 25 acres, Grenouilles is the smallest of the Chablis Grand Cru appellations. Because it lies next to the Serein, a beneficial moderating effect comes into play and when combined with its exceptional south and southwest exposure guarantees an excellent opportunity for long, slow ripening. The poor and stony clay soil sits on a bed of Kimmeridgian limestone and marl, adding to the superior draining of this low-lying climat.

The wine shows notes of fresh meadow flowers, white stone fruit and kiwi with a chalky and slightly saline backbone.

Chablis’ Pinnacle

Gilding the Lily 101: We know what to do when life hands us lemons, but when the vineyard hands us Grand Cru crop, the options are interesting. Technical director Grégory Viennois explains the steps involved in creating the Domaine Laroche pinnacle, ‘La Réserve de l’Obédience’:

Laroche owns 11 acres, or just over one-third of Grand Cru Les Blanchots, and maintains that is their favorite plot of earth in Burgundy. This is in part due to Blanchots’ unique soil composition, combining typical Chablis Kimmeridgian limestone with ammonites and a layer of white clay. Blanchots takes its name from this white clay which retains moisture and protects the vines from hydric stress.

With eastern and southern exposures on a steep slope where elevations range from 500 to700 feet, these old (70+ years) Blanchots vines ripen with a matchless minerality and aromatic richness due to soil, orientation and intensive viticulture: More than 30 people are dedicated to caring for Domaine Laroche vineyards, with each person responsible for only one plot. Domaine Laroche practices ‘lutte raisonnée, or ‘reasoned protection’, using chemical intervention only when required. The vineyard is plowed to aerate the soil and encourage development of the root system, as well as the organic life in the soil; vines are pruned and trained by hand, with a strict pruning and debudding regimen.

“The grapes are hand-harvested in Grand Cru Les Blanchots and collected in small crates to go to the winery, where they are sorted. Then, each parcel is kept apart in order to do the entire winemaking process separately. Blending of the best wines from Grand Cru Les Blanchots takes place at the beginning of the summer every year—samples are taken from each vat, cask and barrel and are then tasted and selected for their delicacy and silky outlines. The aim is to express in the glass the typicity of the terroir as faithfully as possible. We try to get nearer to the perfect wine if it exists: refined, intense, mineral and capable of maturing for at least twenty years.”

Domaine Laroche ‘La Réserve de l’Obédience’, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Blanchots ($234)

Domaine Laroche ‘La Réserve de l’Obédience’, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Blanchots ($234)

Up front, notes of elderflower, vanilla and apple aromas and flavors converge. There is gobs of mid-palate richness above vivid acidity. Within a few years, look for the emergence of exotic aromas of petrol, quinine and pear scents to precede the appealing and concentrated minerality.

Domaine Laroche ‘La Réserve de l’Obédience’, 2019 Chablis Grand Cru Les Blanchot ($193)

Domaine Laroche ‘La Réserve de l’Obédience’, 2019 Chablis Grand Cru Les Blanchot ($193)

Regardless of vintage La Réserve de l’Obédience is a delicate and subtle wine that showcases a markedly different style in its youth than in its maturity. Up to five years, the white fruit aromas, the mineral-driven finish and the extraordinary freshness remain front and center. With a few more cellar years, the inherent richness of terroir is expressed at its best and the soft spices and acacia honey notes, still supported by the freshness, emerge to center stage.

A note …

About Joyce and Bloom

In the Roaring Twenties, such literary eroticism had its price: ‘Ulysses’ was banned in the United States from 1922 (the year it was published) to 1933, a period of time that roughly mirrors Prohibition. James Joyce’s iconic novel follows—in minute and exhilarating detail—three Dubliners as they meander through the course of a single day, June 16, 1904, and is today considered one of the most important works of literature ever composed.

Much of the action in ‘Ulysses’ takes place in pubs, where Leopold Bloom—the novel’s main protagonist—shows a particular penchant for Burgundy. In a passage that made the very real ‘Davy Byrne’s Pub’ famous, Bloom orders a Gorgonzola sandwich along with his customary glass of Burgundy.

“Glowing wine on his palate lingered swallowed. Crushing in the winepress grapes of Burgundy. Sun’s heat it is. Seems to a secret touch telling me memory. Touched his sense moistened remembered. Hidden under wild ferns on Howth below us bay sleeping: sky. No sound. The sky… O wonder! Coolsoft with ointments her hand touched me, caressed: her eyes upon me did not turn away. Ravished over her I lay, full lips full open, kissed her mouth. Yum…. She kissed me. I was kissed. All yielding she tossed my hair. Kissed, she kissed me.”

- - -

Posted on 2024.06.15 in Chablis, France, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

Châteauneuf-du-Pape Finds Its Balance: Two Domaines Show The Craveable Attraction of The Wine’s Combined Intellectual and Hedonistic Elements

Gifts Fit For A Great Father’s Day

Fathers come in all stripes and strengths, of course, and so no wine can serve as a ‘one-size-fits-all.’ But if ever a wine comes close, it’s Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Or, for our purposes, Châteauneuf-du-Papa.

Like any patriarch worth his salt, Châteauneuf matures with grace but is approachable at any age. Like any good mentor, Châteauneuf is a wealth of insight into a number of subjects—in this case, the cornucopia of grapes that make up its essence. Châteauneuf is a bit rustic and at times, may be rough around the edges, but in general, overdelivers on a promise of exuberance while retaining a brooding core—qualities that intermingle as the years go by. Like the role that a father may play in our lives and imaginations, Châteauneuf-du-Pape remains a timeless example of muscle and guidance from which there is always something new to learn.

‘Age before beauty’ is an expression that champions wisdom over looks, and it’s a concept with a lot of meaning in a discussion about terroir. The primacy of place—the philosophy under which a wine should reflect its specific acre of origin—is one of the fundamental Grails of winemaking, especially in France. And this is a quality which a given wine may not express in the bloom of youth, when fruit and façade remain in the forefront. It takes years in the bottle before a wine’s primary flavors have settled; only then do the earthy underpinnings emerge.

If recognizing terroir is your intent, then age before beauty is your shibboleth.

But this is less important if the celebration you’re after is wine’s hedonistic side, and this is why youthful wines are so primally enjoyable.

Not many appellations produce wines that excel in equal measure regardless of age, albeit for different reasons. Châteauneuf-du-Pape is one of them, and this week, we’ll take a look at the product of two outstanding CdP estates, Chapelle St. Théodoric and Domaine Pierre Usseglio & Fils. Both domains produce wines that are sensuous gems in their youth and powerhouses of sophistication in their mature years. And as vital to an understanding this mystical metamorphosis, we’ll look at some details of the vintages that produced them.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape

Peak Expression Of The Wines Of Southern Rhône

Châteauneuf-du-Pape in France’s Rhône valley has traditionally been viewed as a rustic cousin to the elegant and long-lived persistence of great wines from Bordeaux and Burgundy. Châteauneuf is age-worthy, certainly, but there is exuberance in the fresh fruit flavors that dominate the style that makes it decadently drinkable virtually from the day it is released. It was said to make up for in pleasure what it lacked in sophistication.

With more than 8,000 acres under vine, Châteauneuf-du-Pape is the largest appellation in the Rhône, producing only two wines, red Châteauneuf-du-Pape, representing 94% of the appellation’s output, and white Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Of the eight red varietals planted, Grenache is the most dominant variety by far, taking up 80% of vineyard space, followed by Syrah, Mourvèdre and tiny quantities of Cinsault, Muscardin, Counoise, Vaccarèse and Terret Noir.

Untrained Old Vines Grenache Bush in Galets Roulés

Grès Rouge, Sand and Safre

Terroir varies and can only be viewed as a generalization; limestone soil predominates in the western part of Châteauneuf-du-Pape; sand and clay soil covered with large stones on the plateaus. Mixed sand, red and grey clay, and limestone can be found in the northern part of the appellation, less stony soil alternating with marl in the east and shallow sand and clay soil on a well-drained layer of gravel in the south. The large pebbles contribute to the quality of the vines and grapes by storing heat during the day and holding water.

Like the soils, there is an enormous diversity of winemaking styles among CdP producers, creating both appealing, easy-to-understand fruit-filled wines as well as wines of greater intensity and sophistication.

Chapelle St. Théodoric

Chapelle St. Theodoric is the domain that isn’t a domain, at least not in the usual sense of the word. Since 2009, grapes come from two lieux-dits in the CdP have been vinified under the direction of American wine importer Peter Weygandt while the vines are cultivated by the team from nearby Domaine de Cristia.

Baptiste Grangeon (right) Domaine de Cristia

The lieux-dits Guigasse and Pignan were chosen for their sandy soil and nearly stone-free surfaces. Both parcels contain only Grenache vines at an average age of 50 years with some over one hundred. The vineyards are biodynamic and the yields are low—around 14 hectoliter/hactare. Compare this to the legally permitted 35 hl/ha and the average for the appellation at 32 hl/ha.

The genuine ‘Chapelle Saint-Theodoric’ is an old chapel situated by the parking place in the center of Chateauneuf-du-Pape at Avenue Baron le Roy. The chapel is one of the oldest historical buildings in town. It’s used for expositions and has no relation to the vineyard.

Peter Weygandt has been an importer of French wines since 1987 and has gained an international reputation for the quality of his selections and his portfolio of top boutique French, Italian, German, Austrian, Georgian, Spanish and Portuguese wines.

A Clear Sense Of Place

From its inception in 2009, the mission of Chapelle St. Théodoric has been to display the pure and expressive complexities of Grenache as interpreted by winemaker Baptiste Grangeon. The experiment is to see how, with identical treatment of the fruit, the subtleties of two proximate terroirs can be identified. La Guigasse is planted on sandy soil and the Le Grand Pin parcel on higher soil at the top of Pignan, literally adjoining the vines of Château Rayas.

Chapelle St. Théodoric

The vinification is traditional whole-cluster such as that employed by Jacques Reynaud at Château Rayas, Laurent Charvin, Henri Bonneau. The two parcels are vinified, aged and bottled separately, but with the exact same treatment, and the challenge is to find what terroir differences one might find in pure sand, between vines less than 200 meters apart.

The difference between the wines from these two parcels is clear and distinct: La Guigasse is the slightly richer of the two while Le Grand Pin, perhaps because the sand is nearly pure white, perhaps the higher elevation or due to some other factor yet to be determined, makes a wine that is lower in alcohol, more perfumed and finer.

The 2021 Vintage: Year Of The Vigneron

Precocious is a dangerously loaded word, whether it is used to describe a child or a vintage. It generally means that things are happening out of sequence, earlier than is usual. 2021 was such a season in Southern Rhône, and the rumbles of discontent began the year before. Autumn, 2020, was mild and damp and the season remained so until a short cold spell happened in January ʼ21. In February, Saharan winds brought unseasonable highs that reached into the mid-60s°F, advancing the vegetative cycle throughout the vineyards. Vines, if not growers, love these unseasonable warm spells, leaving them easy targets for one of a vigneron’s worst nightmares— spring frost. Sure enough, during the first week of April, a catastrophic frost lambasted the vineyards and across Châteauneuf-du-Pape, reports indicated potential losses of up to 80%. The double-whammy of frost is not only seen in the damage it inflicts at the time, but that it leaves grapes weaker and more susceptible to fungal disease in the weeks to come. To aggravate this latter risk, the rest of the spring was humid, with heavy rains accompanied by cooler temperatures and less than average sunshine, raising fears of coulure (uneven ripening).

In Châteauneuf-du-Pape, the catastrophe saw a 70% reduction in yield in a few spots, but overall, the impact was ameliorated by the proximity of the Rhône River. Even so, in 2021, the skill of the winemaker came to the forefront. Every vigneron in the appellation had issues to deal with and questions to consider, including the use of whole bunch (weighing its aromatic benefits against the risk of underripe stalks), the amount of oak to use, how strictly to sort grapes, and in particular, how much to alter their blend in the varieties or vineyard plots they could draw from.

It is fair to say that the best domains did splendidly, creating wines in classical CdP style, meaning, possessed of exceptional elegance and incipient freshness, fruit not bogged down by alcohol. Managed well, cooler temperatures permit a long, slow ripening period and produce grapes with full phenolic ripeness but lower sugars. This leaves alcohol levels blissfully low compared to recent averages, and a welcome change to some of the headier wines of some vintages.

Chapelle St. Théodoric ‘La Guigasse’, 2021 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($99)

Chapelle St. Théodoric ‘La Guigasse’, 2021 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($99)

Possibly the wine of the vintage; on the nose, intriguing spices waft over herbal and savory notes to provide a compelling counterpoint to cherry and raspberry perfume, while the full-bodied palate is concentrated and sappy, finishing bright, fresh and long.

Chapelle St. Théodoric ‘Le Grand Pin’, 2021 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($108)

Chapelle St. Théodoric ‘Le Grand Pin’, 2021 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($108)

From 35-year-old Grenache vines in Pignan, this is a floral, ethereal expression of Chateauneuf-du-Pape marked by scents of roses, lavender, strawberry compote and hints of pine resin. The 2021 Châteauneuf Du Pape Le Grand Pin offers a slightly fresher style compared to the La Guigasse, which always tends to be a slightly more powerful wine.

The 2016 Vintage: Benchmark Vintage, Truly Rare

The 2016 vintage in Rhône was dominated by warm days and cool nights; ideal conditions for growing top-shelf Cinsault, Mourvèdre, Grenache and Syrah. Preceded by a relatively mild winter, the spring was dry and cool and summer exploded with plenty of sunshine and heat. September rains replenished the reservoirs enough to allow each variety to reach full phenolic ripeness. Harvest began in mid-September and, depending on vine age and terroir, some growers continued grape picking until early October. Châteauneuf red wines from this vintage are creamy and concentrated with silken texture and brilliant fruity richness, while the whites, full-bodied richness, remarkable complexity and sensational freshness.

Chapelle St. Théodoric ‘La Guigasse’, 2016 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($99)

Chapelle St. Théodoric ‘La Guigasse’, 2016 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($99)

Dark-berry brawniness overlies the raspberry compote, with earth and minerals on the nose and fleshing out in the mouth.

.

The 2015 Vintage: Rich, Ripe And Full Of Powerful Fruit

Although the Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s 2015 vintage was slightly challenging for the slow-ripening Grenache, talented winemakers rose to the occasion by producing wines with superior tannins and ripe fruit if slightly higher levels of alcohol.

In early September, the entire Rhône Valley saw heavy rain, which favored the vines planted on free-draining sand and resulted in fresh fruit-forward flavors and expressive minerality. The best domains produced age-worthy wines with complex flavors and sumptuous textures.

Chapelle St. Théodoric ‘La Guigasse’, 2015 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($83)

Chapelle St. Théodoric ‘La Guigasse’, 2015 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($83)

Highly expressive, mineral-accented aromas of baked cherry and incense that pick up toasted earth element over a cherry core. Precise in the mouth with intense red fruit liqueur, a touch of acidity and a generally autumnal nature.

The 2010 Vintage: Terroir-Driven, For Aging

The summation of 2010 vintage in Châteauneuf-du-Pape is ‘low volumes but very high quality.’ Although climate specialists described the climate of this vintage as cooler and wetter than usual, there was shatter (floral abortion) on the Grenache during springtime and hydric deficiency in July and August, explaining the low yield.

2010 was a season of extremes; CdP experienced 55 days during which temperatures were higher than 86°F along with 46 days of frost (compared to a more standard 30). From October 2009 to September 2010, rainfall was 23% higher than average, but lower than average in July and August. During the agricultural year, total rainfall was close to 31 inches (average is 25 inches) making this period one of the wettest in terms of rainfall over the past 139 years.

As in 2009, this vintage’s quality and characteristics are due to the climatic conditions: a rainy springtime and a dry summer enabled the grapes to be healthy and build an interesting tannic structure. During harvesting, sorting was minimal and everything proceeded smoothly, apart from a storm at the beginning of September, leading to superb results across the board.

Chapelle St. Théodoric ‘La Guigasse’, 2010 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($169)

Chapelle St. Théodoric ‘La Guigasse’, 2010 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($169)

100% Grenache, not destemmed, and aged and fermented in older demi-muids. It shows the typical Guigasse herbal streak, especially menthol and pine needles, and the richness of Guigasse fruit that one can expect. Full-bodied blackberry, violets and chocolate all emerge with air contact, so let it breathe; it is nicely balanced with a great mid-palate and a long, silky finish.

Domaine Pierre Usseglio & Fils

The quintessence of Châteauneuf-du-Pape is the conviction that the sum of parts is greater than the whole. As such, Domaine Pierre Usseglio maintains 60 acres of vines spread out across the entire region, maintaining property in 17 individual lieux-dits with one plot set aside for the production of white wine. The red-wine holdings are planted to 80% Grenache, 10% Syrah, 5% Mourvèdre, 5% Cinsault; vine age ranges from 30 to 75 years of age. A sizeable portion of the CdP vineyard sits within famous La Crau, ancient confluence of the Durance and Rhône rivers; the rest climbs the hill across the road from the actual ruins of the castle from which Châteauneuf-du-Pape gets its name.

Grégory Usseglio

The estate also owns 15 acres of Côtes-du-Rhône, another 15 in Lirac and another five acres that it bottles as ‘Vin de France.’

Says Jean-Pierre: “We work our vineyard manually, and with respect throughout the seasons. We let nature express itself freely. It is thanks to this difference in terroir that we can offer complex, silky and balanced wines; our vines are spread across multiple sites where the soils range from limestone and rolled pebbles, to sand and sandstone flecked with clay. These are the voices of the earth and we are committed to listening.”

Fierce But Lovable, The ‘Proverbial’ Brooding Wine

Spencer Tracy, James Dean, Ron Perlman to name but a few: Brooding, fierce actors who are also lovable.

In the world of wine, no example is more striking than that of Usseglio’s Châteauneuf-du-Pape; the proverbial brooder that also offers a candy store’s worth of fruity delights—cherry to blueberry to deep rich raspberry. The earthiness, quite literally, grounds these flavors, but it is an easy wine to cozy up to, especially when young. The evolution that slowly supplants the chewy fruit with Provençal herbs and leathery forest tones offers a neophyte drinker some time to develop a passion for such tertiary flavors. That gives CdP a great profile, depending on how long it has been allowed to brood, as if Ron Perman played both the Beauty and the Beast.

The 2020 Vintage: Supple Fruit, Accessible Tannins, Stands Out For Immediate Drinkability

Following the extreme heat of 2019, growers were hoping for plenty of rainfall over the winter to replenish aquafers, and they got it. An astonishing 15-20 inches of rain fell between October and December, and a mild early spring saw vine buds break nearly two weeks earlier than in 2019. The summer was hot, but not unreasonably so; rains were moderate and frequent enough to prevent heat stress. Harvest for white grapes began in the third week of August, and the 2020 vintage is extremely strong in this category, however small (only 5% of Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s total). It is characterized by elegance and beauty, with a nose marked by citrus and stone fruit and a palate that combines balanced acidity with a prolonged finish.

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Tradition’, 2020 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($45)

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Tradition’, 2020 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($45)

Tradition 2020 is a blend of 80% Grenache, 10% Syrah and 5% each Mourvèdre and Cinsaut; it shows an aromatic bouquet of red berries, plum with subtle of dried herbs. The palate echoes the nose, with an enduring and balanced finish suggesting impression of structure and finesse.

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Tradition’, 2020 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($128) 1.5 Liter

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Tradition’, 2020 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($128) 1.5 Liter

Same wine as above in magnum.

Domaine Pierre Usseglio, 2020 Châteauneuf-du-Pape Blanc ($67)

Domaine Pierre Usseglio, 2020 Châteauneuf-du-Pape Blanc ($67)

2.5 acres is used in the production of this blend of 70% Clairette, 25% Grenache Blanc and 5% Bourboulenc, fermented and matured in a mix of vessels including stainless steel, barrels and amphorae. Fragrant and youthful with a wonderful salinity below flavors of white peach, pears and apples with some pronounced flintiness; the wine has excellent grip and bold extract with multiple layers that continue through a long finish.

Réserve des 2 Frères

Domaine Pierre Usseglio Réserve des Deux Frères made its debut with the 2000 vintage. The name was changed to ‘Réserve des 2 Frères’ in 2007 along with a label redesign.

The wine is made from the estate’s oldest Grenache vines. Previously made with 10% Syrah, this only rarely the case today, although a small percent of Syrah went into vintage 2020. Grapes are usually completely destemmed; the level of stem retention depends on the vintage.

Slightly more modern in style than the tradition-heavy ‘grandfather’ wine ‘Mon Aïeul,’ ‘Two Brothers’ is aged in a combination of 10% new demi-muids and 10% new oak barrels along with a combination of one- or two-year-old French oak barrels, where it ages for 12-20 months. Domaine Pierre Usseglio Reserve des 2 Frères is not made every year, and when it is, only 500 cases are produced.

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Réserve des 2 Frères’, 2020 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($179)

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Réserve des 2 Frères’, 2020 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($179)

A splash of Syrah in the 2020 bottling leads to a fresh and focused wine, balanced, toasty and loaded with raspberry liqueur, crème de cassis, graphite, smoke meats, licorice that combines power and elegance.

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Réserve des Deux Frères’, 2015 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($207)

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Réserve des Deux Frères’, 2015 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($207)

Grenache (per se) is not always the best candidate for aging; it possesses a naturally low concentration of phenolics, which contribute to its pale color and lack of extract. With a propensity for oxidation, Grenache-based wines tend to be made for early consumption.

But in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, under the hands of skillful viticulture and planted in marginal soil with restricted yields, all that changes. The vibrant fruit of young Grenache mellows and spice box tones come out with leather, and in this wine, tar, black olives and tobacco.

The 2019 Vintage: Grenache Excels As Harvest Lingered Into Early October, An Elite Vintage

As a variety, Grenache enjoyed a marvelous renaissance in 2019, and for this sun, heat and wind-loving variety, 2019 provided ideal conditions throughout Southern Rhône. An abundant fruit set was followed by three heat waves interspersed with rain and more moderate temperatures, and as a result, there was no stress for the vines and ripening never shut down. Growers were able to pick at optimum ripeness and nothing much had to be done in the vineyard. The fruit’s health carried through to the cellar, with many growers reporting that their vinification were fast and efficient.

Cuvée de Mon Aïeul

Usseglio’s flagship wine produced from highly selective plots that narrow lieux-dits down still further. Only Grenache vines between 75 and 90 years old are used, originating from La Crau, Bédines and Serres. No destemming is done and fermentation lasts for 30-40 days.

Having made its debut in 1998, and translating to ‘My Grandfather’, Mon Aïeul has been made from 100% Grenache since 2020; previously, 5% Syrah was used in the blend. Half of each year’s blend wine is aged for 12 months in used demi-muids while the remained is aged in concrete tanks. Production averages 650 cases per year.

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Cuvée de Mon Aïeul’, 2019 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($124)

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Cuvée de Mon Aïeul’, 2019 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($124)

Full-bodied, lusciously textured and round, showing upfront notes of Asian spice, cocoa, and mint with a palate loaded with blackberry, kirsch and raspberry behind a granite-shale minerality.

Not For You!

From the oldest vines of the estate, Usseglio’s quirkily named ‘Not For You!’ originates in the estates oldest Grenache vineyards and is not made every vintage. It was made for the first time in 2007, from the Les Serres lieu-dit when Thierry Usseglio and consulting winemaker Baptiste Olivier ended up with one particular barrique that contained over 17% alcohol after the fermentation finished. According to Usseglio, Josh Raynolds tasted it and then wrote down in his notes that this wine, because of its sheer concentration and intensity, is “Not for You!”. Usseglio loved this statement and spontaneously decided to name this particular cuvée following Josh’s comment. Since, it has been bottled in 2009, 2010, 2016 and 2019.

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Not For You!’, 2019 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($399)

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Not For You!’, 2019 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($399)

Despite the obvious wood influence, floral elements shine through cedary notes, adding nuance to the flavors of black cherries, plums and milk chocolate. The wine is full-bodied and supple, with crisp acids over notes of bark and earth. There is a ‘long-haul’ expectation here that is poised to deliver great depth and sophistication down the road. Currently, the wine is opulent, but with the stem and bark notes still prominent, with a bitter chocolate-covered cherry notes.

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Not For You!’, 2019 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($890) 1.5 Liter

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘Not For You!’, 2019 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($890) 1.5 Liter

The same wine in magnum, which will take longer to age to perfection, but will deliver more, as the slower maturation process is almost certain to be a plus—it usually is.

No 18

Talk about a cornucopia! The titular ‘18’ is a reference to the number of grape varieties that go into this co-fermented field blend; at around 5% each, this covers the whole of the ‘allowables’—Grenache Blanc, Grenache Gris, Syrah, Mourvèdre, Cinsault, Counoise, Muscardin, Vaccarèse, Terret, Clairette Blanche, Clairette Rose, Picpoul Noir, Picpoul Blanc, Picpoul Gris, Roussanne, Bourboulenc and Picardan.

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘No 18’, 2021 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($159)

Domaine Pierre Usseglio ‘No 18’, 2021 Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($159)

The grapes are harvested manually, 100% destemmed, and vatting is followed by thermo-regulation that lasts between 20 to 30 days. The wine is then aged in amphorae for a year prior to bottling. It shows young-vine strawberry, cherry and white flowers with pretty, silky tannins to shore it up.

LIRAC

A SHORT HOP ACROSS THE RIVER FROM CHÂTEAUNEUF-DU-PAPE

On the western side of the Rhône River, about six miles north of Avignon, Lirac is a typically Mediterranean wine growing cru, with low yearly rainfall and high sunshine levels (especially during summer and into the harvest months). The famous Mistral wind from the north plays a significant cooling role, and blows, on average, 180 days a year.

Lirac terroir is largely built around elevation; vineyards on the upper terraces of the appellation are made up of red clay and the large pebbles known as ‘terrasses villafranchiennes’, with the soil of the lower vineyards gradually showing more loess and/or clay-limestone. All are prone to summer drought and, under certain strictures, irrigation is allowed.

“The terroir of Lirac is often hidden in the shadows of Châteauneuf-du-Pape,” says Laure Poisson of Les Vignerons de Tavel & Lirac. “But in recent years, Lirac has emerged from the shadows to become something different, something unique.”

Blend makeup in Lirac wines is reasonably focused, with regulations favoring the classic Grenache, Syrah, Mourvèdre (and a bit of Cinsault) blend. Grenache must make up a minimum of 40% of the blend while Syrah and Mourvedre must be over or equal to 25%.

Domaine Pierre Usseglio & Fils, 2020 Lirac ($33)

Domaine Pierre Usseglio & Fils, 2020 Lirac ($33)

Usseglio & Fils’ 2020 Lirac is produced with 50% Grenache, 25% Mourvèdre, 20% Syrah from vines averaging 40 years old. A sweet core of blackberry is enshrouded in notes of black plum, black currant, aniseed and traces of new leather which lend promise to a cellar-worthy gem.

Famille Pierre Usseglio ‘L’Unique’

Greater Than The Sum Of Its Parts

The purpose of inventing the ‘Vin de France’ appellation was purely commercial; for a country whose wines are so inextricably linked to place of origin, a category that allows grapes from anywhere in the country to be used may seem like an odd innovation. But, faced with competition from elsewhere, it allowed winemakers to create a lower-priced product that could compete with New World wines. And, as is the case in a nation of vignerons, VdF wines are (for the most part) of self-evident quality, with many approachable, easy-to-understand prizewinners.

Famille Pierre Usseglio ‘L’Unique’ , 2020 Vin de France Southern-Rhône ($25)

Famille Pierre Usseglio ‘L’Unique’ , 2020 Vin de France Southern-Rhône ($25)

The spirit of VdF is loud and clear from the playful label on this blend of Grenache (40%), Syrah (20%), Mourvèdre (20%), Marselan (15%) and Merlot (5%) macerated for 25 days followed by six months aging in concrete before release. The wine is ripe and fruit-forward with fresh red berries, spring flowers and light spices. Very much an everyday wine that proves the Usseglio clan’s deft hand with all strata of winemaking, even in the level playing field that VdF encourages.

Notebook …

Traditional and Modern Styles

Throughout much of its history, CdP provided a leathery foil to the potent and somewhat austere elegance of Bordeaux and the heady sensuousness of Burgundy. CdP is ‘southern wine’, filled with rustic complexity—brawny, earthy and beautiful. But as a business, all wine finds itself beholden to trends, since moving product is necessary to remain afloat. During the Dark Ages (roughly1990 through 2010—in part influenced by the preferences of powerful critic Robert Parker Jr.) much of Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s output became bandwagon wines, jammy and alcoholic, lacking structure and tannin, in the process becoming more polished than rustic and more lush than nuanced. For some, this was delightful; for others, it was a betrayal of heritage and terroir.

These days, a new generation of winemakers seem to have identified the problem and corrected it. Recent vintages have seen the re-emergence of the classic, balanced style Châteauneuf-du-Pape, albeit at slightly higher prices. A changing climate has also altered traditional blends, so that more Mourvèdre may be found in cuvées that were once nearly all Grenache. Mourvèdre tends to have less sugar and so, produces wine that is less alcoholic and jammy, adding back some of the herbal qualities once so highly prized in the appellation. But a return to old school technique has also helped; however, many of the wines in this offer were destemmed prior to crushing and were fermented on native yeast rather than cultured yeast.

Vineyard Management and Grape Varieties

In 1936, the Institut National des Appellations l’Origine officially created the Châteauneuf-du-Pape appellation, with laws and rules that growers and vignerons were required to follow. It was agreed that the appellation would be created based primarily on terroir (and to a lesser extent, on geography) and includes vines planted in Châteauneuf-du-Pape and some areas of Orange, Court In 1936, the Institut National des Appellations l’Origine officially created the Châteauneuf-du-Pape appellation, with laws and rules that growers and vignerons were required to follow. It was agreed that the appellation would be created based primarily on terroir (and to a lesser extent, on geography) and includes vines planted in Châteauneuf-du-Pape and some areas of Orange, Courthézon, Sorgues and Bédarrides. 15 grape varieties are allowed in the appellation: Grenache, Syrah, Mourvèdre, Terret Noir, Counoise, Muscardin, Vaccarèse, Picardan, Cinsault, Clairette, Roussanne, Bourboulenc, Picpoul Noir, Grenache Blanc and Picpoul Blanc. Vine density must not be less than 2,500 vines per hectare and cannot exceed 3,000 vines per hectare. Vines must be at least 4 years of age to be included in the wine. Machine harvesting is not allowed in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, so all growers must harvest 100% of their fruit by hand.

Beyond that, vines are allowed to be irrigated no more than twice a year. However, irrigation is only allowed when a vintage is clearly suffering due to a severe drought. If a property wishes to irrigate due to drought, they must apply for permission from the INAO, and any watering must take place before August 15.

Climate And Weather

Located within the Vaucluse department, Châteauneuf-du-Pape has a Mediterranean climate—the type found throughout much of France’s south—and characterized by hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters. It rarely snows at sea level (as opposed to the surrounding mountains, where snowfall may be considerable).

As the equal of elevation and rainfall, a third defining feature of the climate in Southern France is the wind. In a land dominated by hills and valleys, it is always windy—so much so that in Provence, there are names for 32 individual winds that blow at various times of year, and from a multitude of directions. The easterly levant brings humidity from the Mediterranean while the southerly marin is a wet and cloudy wind from the Gulf. The mistral winds are the fiercest of all and may bring wind speeds exceeding 60 mph. This phenomenon, blowing in from the northeast, dries the air and disperses the clouds, eliminating viruses and excessive water after a rainfall, which prevents fungal diseases.

- - -

Posted on 2024.06.10 in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Lirac, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Southern Rhone | Read more...

The Enduring Beauty Of Beaujolais Great As Well As Joyous Wines. Distinctive Enough To Bear More Specific Appellations And Individual Parcels. Domaine de Vernus, A New Face, In Five Crus. 7-Bottle Pack For $264

Memorial Day is a time to reflect on mortality as well as to celebrate the rebirth of warmth and leisure time. No wine captures the complexity emotions better than Beaujolais, which can be light and lyrical as well as profound and nuanced. These are ideal wines with which to celebrate Memorial Day, the gateway to summer and the joy of transcendence.

In literature, a character study is a critical examination of a single character to understand not only their significance to a given narrative, but as a way of better understanding the work as a whole. This week, we will undertake a similar focus on a lone, but phenomenal Beaujolais winemaker (Guillaume Rouget of Domaine de Vernus) in order to see how a single talented vigneron can exemplify the moods, the changes, the whims of a region where a diverse terroir remains committed to a single grape variety, Gamay.

Rouget certainly comes with a proper pedigree: The grand-nephew of Henri Jayer (the Burgundian innovator known for making some of the most critically acclaimed and expensive Pinot Noirs in the world), he was trained to the vine from childhood, first by his father Emmanuel Rouget and then at the École des Vins de Bourgogne in Beaune. When he decided to join forces with Domaine de Vernus owner Frédéric Jametton in Régnié-Durette, it was to pursue a shared goal: Producing elegant, racy wines that display the intense fruitiness of Gamay along with age-worthy structure that can develop complexity over time alongside the best Burgundies. Guillaume is in charge of the entire production chain, from cultivation through all phases of vinification, ultimately taking part in the marketing of the estate’s wines. A true renaissance man in Beaujolais, his handling of various top Crus may not be ‘Beaujolais Nouveau,’ but it is very much the new Beaujolais.

Guillaume Rouget with father Emmanuel Rouget, Domaine Emmanuel Rouget in Vosne-Romanée and Flagey-Echézeaux

The Beaujolais Vineyard: Diversity Of Soils, Rocks and Minerals

The biggest error a Beaujolais neophyte makes is an expectation one-dimensional predictability. To be fair, the mistake easy to make based on the region’s reliance on Gamay, a grape that elsewhere may produce simple and often mediocre wine. In Beaujolais’ terroir, however, it thrives.

In fact, this terroir is so complex that it nearly defies description. But Inter-Beaujolais certainly tried: Between 2009 and 2018, they commissioned a colossal field study to establish a detailed cartography of the vineyards and to create a geological snapshot of the exceptional richness found throughout Beaujolais’s 12 appellations.

Beaujolais may not be geographically extensive, but geologically, it’s a different story. The region bears witness to 500 million years of complex interaction between the eastern edge of the Massif Central and the Alpine phenomenon of the Tertiary period, leaving one of the richest and most complex geologies in France. Over 300 distinct soil types have been identified. Fortunately, Gamay—the mainstay grape, accounting for 97% of plantings—flourishes throughout these myriad terroirs. In the south, the soil may be laden with clay, and sometimes chalk; the landscape is characterized by rolling hills. The north hosts sandy soils that are often granitic in origin. This is the starting point wherein each appellation, and indeed, each lieu-dit draws its individual character. There are ten crus, the top red wine regions of Beaujolais, all of them located in the hillier areas to the north, which offer freer-draining soils and better exposure, thereby helping the grapes to mature more fully.

A Palette Of Ten Crus

Beaujolais is a painter’s dream, a patchwork of undulating hills and bucolic villages. It is also unique in that relatively inexpensive land has allowed a number of dynamic new wine producers to enter the business. In the flatter south, easy-drinking wines are generally made using technique known as carbonic maceration, an anaerobic form of closed-tank fermentation that imparts specific, recognizable flavors (notably, bubblegum and Concord grape). Often sold under the Beaujolais and Beaujolais-Villages appellations, such wines tend to be simple, high in acid and low in tannin, and are ideal for the local bistro fare. Beaujolais’ suppler wines generally come from the north, where the granite hills are filled with rich clay and limestone. These wines are age-worthy, and show much more complexity and depth. The top of Beaujolais’ classification pyramid is found in the north, especially in the appellations known as ‘Cru Beaujolais’: Brouilly, Chénas, Chiroubles, Côte de Brouilly, Fleurie, Juliénas, Morgon, Moulin-à-Vent, Régnié and Saint-Amour.

Each are distinct wines with definable characteristics and individual histories; what they have in common beyond Beaujolais real estate is that they are the pinnacle of Gamay’s glory in the world of wine.

2020 Vintage: Rhône Scents. Bathed in Sunshine.

If you can invent a way to leave Covid out of the equation, 2020 was a wonderful vintage throughout Beaujolais. The growing season was warm, beginning with a mild and frost-free spring, which developed into a hot and sunny summer without hail or disease. Drought—a persistent worry in the region—was not as severe as it might have been, and by harvest-time the majority of grapes were in fine health with rich, ripe, almost Rhône-like flavors—raspberries, sour cherry and even garrigue; the local scrub comprised of bay, lavender, rosemary and juniper.

2020 yields were low due to the dry conditions, leading to concentrated juice and wines able to benefit from time in the cellar.

But, of course, you can’t leave Covid out of the equation: Normally the release of Beaujolais Nouveau occurs on the third Thursday of every November, but in pandemic-dominated 2020 the normal celebrations could not take place and producers instead chose to release the wines a week earlier than usual in order to allow for international shipping times.

Domaine de Vernus

After thirty years in the prosaic world of insurance brokerage, Frédéric Jametton decided to do a rakehell turn on his career trajectory. Having been born in Dijon and lived in Burgundy for most of his life, he had become an enlightened wine lover. Not only that, but his former profession brought him in contact with numerous members of the wine community. At the end of 2017, he realized that the time had come to invest in a winery.

Winemaker Guillaume Rouget, left, with Frédéric Jametton, Domaine de Vernus

Initially looking in the south, he became convinced that the heat spikes brought on by climate change made it unsuitable for the long haul, and after discussions with his friend Guillaume Rouget of Flagey-Echézeaux (who agreed to come on board as a consultant) Jametton settled on Beaujolais, piecing together 30 acres of vineyards acquired from 12 different proprietors, and is gradually restructuring parcels with a view to more sustainable farming.

Thanks in part to Rouget’s influence, vinification is conducted along Burgundian lines, with around 70% of the grapes destemmed and fermented in stainless steel with élevage in recently-used, high-quality Burgundy barrels for some 10–11 months. Jametton’s ultimate goal, echoed by Rouget, is to offer a range of wines that brings out the best of the different terroirs while respecting the character and personality of each Cru and each plot.

With Rouget in charge of the vineyards and winemaking process, Frédéric remains at the management helm and spearheads marketing.

Beaujolais-Villages: Gamay in Full Bloom

Of the three Beaujolais classifications, Villages occupies the middle spot in terms of quality. To qualify, the wine generally hails from more esteemed terroirs in the northern half of Beaujolais, from one of 38 villages that have not been named ‘cru’ appellations. They are expressive wines with more structure and complexity than generic Beaujolais, though not as exclusive as those from the ten crus. Accounting for about a quarter of all Beaujolais production, Villages wines are most often produced by négociants and vinified using stricter rules as to yields and technique.

1 Domaine de Vernus, 2020 Beaujolais-Villages ($27)

1 Domaine de Vernus, 2020 Beaujolais-Villages ($27)

80% whole cluster fermentation from vines around 35 years old; the grapes are subject to alternate grape-treading, pump over, and ‘delestage’—a two-step ‘rack-and-return’ process in which fermenting red wine juice is separated daily from the grape solids by racking and then returned to the fermenting vat to re-soak the solids. Fermentation on wild yeast for two weeks. A fruit-forward, juicy wine with expressive aromas of strawberry and spicy black cherry.

*click on image for more info

Régnié: The Gateway to Beaujolais

Many Beaujolais wines are best consumed in their youth, and this is a quality emphasized with gusto by Régnié, the youngest of the Beaujolais crus. In fact, it wasn’t until 1988 that a group of 120 wine growers lobbied to get the appellation officially recognized, pointing out the newcomer in the family has plenty to offer: Its favorable geographical location between its two brothers, Brouilly and Morgon, allows the production of wines of a unique fruitiness.

Often called the ‘Prince of the Crus’, Régnié’s terroir is distinguished by the pink granite soils found high in the Beaujolais hills. Here, at some of the highest altitudes in the region, vines are planted on coarse, sandy soils that are highly permeable and drain freely, an environment which is well suited to the Gamay grape variety.

Further down the slopes, higher proportions of clay with better water storage capabilities lead to a slightly more structured style of wine. The variation within the vineyard area allows growers to produce everything from fresh, light wines to heavier, more age-worthy examples of Régnié.

2 Domaine de Vernus, 2020 Régnié ($30)

2 Domaine de Vernus, 2020 Régnié ($30)

From vines with an average age of 42 years. 100% destemmed with three weeks of fermentation time on native yeasts followed by ten months maturation, half in oak barrels and half in stainless steel tanks. The wine has a lively acidity behind notes of sour cherry kirsch with hints of agave and pepper.

*click on image for more info

Domaine de Vernus, 2019 Régnié ($72) 1.5 Liter

Domaine de Vernus, 2019 Régnié ($72) 1.5 Liter

Same wine, in 2019, in magnum, allowing for a slower maturation process in the cellar.

*click on image for more info

Chiroubles: A Terroir in Altitude