New Energy in the Less Familiar Territory of Touraine in The Heart of The Loire Valley; A Place Where Talented Artisanal Vignerons are Introducing Changes and Reinvention. Two Packs: Red Touraine 11-Bottle Pack ($369) & White Touraine 12-Bottle Pack ($369)

Touraine may not grab the vinous headlines of, say, Sancerre or Vouvray, but in ways it is the aesthetic paradigm for the region: Made of castles and gardens and vineyards lining the capricious and majestic Loire from Anjou in the west to Sologne in the east, Touraine winds its way through communes in Indre-et-Loire and Loir-et-Cher.

As part of the Paris Basin, the terroir here is a blend of flinty clay, alluvial river gravel and the unique chalky, fine-grained limestone known as ‘tuffeau.’ White to yellowish-cream in appearance it contains trace levels of mica, and is in part responsible to the longevity of the wines it produces.

There’s more: Since the life of a natural vigneron is often about withdrawing from much of the socio-financial contract of modern urban life, it’s natural that many have sought out the lesser known Loire heartland—Touraine—to set up shop. Not only that, but there is also a generational change among the historic estates, where a new generation of ecology-conscious heirs have revamped old techniques with a new respect for the earth.

Thirst-Quenching Wines to Slake Summer Thirst

Capable of producing prestigious wines with promising futures, Touraine is also the home of wines which can kiss warm weather with the cool embrace of simplicity. These are beautiful representations of their varietals, produced in a style that emphasizes the lyrical, rather than the contemplative side of wine. They are also priced at a point in which you require no occasion more special than this afternoon to enjoy them.

And despite a common misconception, we’re not talking about white wines exclusively. Reds have carved out their own niche in Touraine, and the ones that serve summertime best are those low in alcohol and cooled to a refreshing temperature.

Orange wine is also produced here—see the entry below.

Upriver in Touraine: A Multitude of Soils and Grape Varieties

The vineyards of Touraine grow at the crossroads of oceanic and continental influences, and likewise, the soils are as varied as the breezes, being predominantly limestone, sand and siliceous clay from the Paris Basin, while the terraces bordering the Loire and the Vienne contain deposits of pebbles smoothed to roundness by the action of the water. Such variety supports a cornucopia of grape varieties and multifarious styles—easy-drinking white, red and rosés and sparkling wines along with sweet wines that will bend your mind as they crumble your molars. Whether red, white or shades between, Touraine wines are always vibrant with acidity and delicate, precise flavors.

Known locally as known locally as Pineau Blanc de la Loire, Chenin accounts for much of Touraine production; they are dry, fairly firm, lively and full, and keep well when bottled. The sparkling wines are allowed to use the designation Touraine mousse (sparkling Touraine wine). Up to 20% of Chardonnay grapes may be included in the mixture of varieties grown.

Red wine is produced from Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Côt, Pinot Noir, Meunier, Pineau d’Aunis and Gamay grape varieties and tend to be firm.

Talented Artisan Vignerons in Touraine: A Quiet Revolution

Land at bargain basement prices in the Garden of France? Touraine, bolstered by the presence of the SAFER group (which controls the sale of agricultural land) is so welcoming to newcomers that it seems an obvious destination for new artisanal winemakers looking to make their mark. This is not a new phenomenon; the AOP has been attracting new waves of natural winemakers since the 1990s.

In fact, so flexible has the region been for young iconoclasts leaning toward experimentation that a new dilemma has arisen: How to find the ideal style and substance to best showcase Touraine’s remarkable terroirs? Ancient varieties like Pineau d’Aunis have retained a foothold while standbys like Sauvignon Blanc are being shifting to supporting roles. As always, tuffeau and flint produce a compelling expression of Chenin—one that is edgier and more bracing than elsewhere—and as these wines grow more popular, another quandary may loom among these talented freshmen (and freshwomen): How can they avoid becoming a monoculture appellation driven by financial success where everyone is chasing the same thing?

Red Touraine 11-Bottle Pack ($369) and White Touraine 12-Bottle Pack ($369)

A Touraine travelogue in wine, covering the best of our collection. This package showcases the revolution in style and substance that keeps Touraine at the forefront of innovation, and where (in a growing world of multinational wine companies) winemaking remains a family affair.

Coteaux-du-Loir

Limited to 22 communes in a rather obscure viticultural whisper just to the north of Touraine, Coteaux-du-Loir produces from a scant 180 acres of vines. The appellation is classified as part of the Loire Valley group even though it does not lie in the valley itself. In fact, the river it follows is the Loir, not the Loire, inevitable confusions notwithstanding.

52% of the vineyards are red wine varieties (primarily Pineau d’Aunis) but of most interest to wine lovers is the whites made from Chenin. They may vary from bone dry and steely to incredibly sweet—honey-scented botrytized wines that bear a passing resemblance to Savennières and Vouvray, although they generally lack the richness and finesse of these better-known wines.

Maison Gazeau-Baldi

(Coteaux-du-Loir)

Perched atop the Jasnières hillside in Lhomme, Maison Gazeau-Baldi is home to Aurély and Jean-Damien, whose modest 20-acre vineyard—currently in the midst of conversion to organic and biodynamic agriculture—has been making quality waves throughout their small appellation. The couple has been able to extract remarkable character from Chenin, Gamay, Côt and Pineau d’Aunis.

Organics is a concept on which the couple has entirely bought into. Says Aurély: “We seek balance in order to think of the vineyard as an ecosystem rather than a material. We work clay soils to obtain a filtering texture while freeing the vine from its competitors. The manure is mainly of animal origin; we prefer cow. We carefully select the buds, and sulfur and copper treatments are minimal and always combined with plant extracts. The harvest is entirely manual, with systematic sorting. The harvest is an opportunity to live a moment of sharing and meetings.”

Jean-Damien and Aurély Gazeau-Baldi, Maison Gazeau-Baldi

Jean Damien adds, “It’s a philosophy that carries through to the cellar. We value the potential of each plot, according to the vintage, then deliver an interpretation by choices of pressing, maceration, racking and aging time, without ever copying a process. We strive to listen to the directions taken by wine and adapt to them. The use of sulfur is minimal and antiseptic in principle. We gladly expose wines to oxygen with the idea of strengthening them. We are in the first year of organic conversion with the ECOCERT organization—labels are, above all, a way to make our practices more readable for consumers and partners. We plan to continue our approach with biodynamic certification.”

1 Maison Gazeau-Baldi, 2022 Coteaux-du-Loir Rouge ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ ($33)

1 Maison Gazeau-Baldi, 2022 Coteaux-du-Loir Rouge ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ ($33)

80% Pineau d’Aunis, 20% Côt from vines ranging from 5 to 70 years old. The d’Aunis sees whole bunch maceration with regular punch-downs for 20 days; the Côt is directly pressed. The wine pours a light red color and exhibits raspberry and strawberry mixed with earth and spice highlighted with a touch of pepper. Chilled for 15 minutes or so, it is a delightful companion for a charcuterie board. 11,000 bottles produced.

1 Maison Gazeau-Baldi ‘Rendez-Vous’, 2022 VdF Loire-Atlantic Blanc ‘Chenin’ ($25)

1 Maison Gazeau-Baldi ‘Rendez-Vous’, 2022 VdF Loire-Atlantic Blanc ‘Chenin’ ($25)

100% Chenin Blanc crafted from vines less than 10 years old; this is an extremely limited production of 7,000 bottles. Having undergone a meticulous vinification process involving gentle pressing and cold settling, the wine shows fresh peach, grapefruit and a solid saline core.

Touraine Azay-le-Rideau

Even smaller in size than Coteaux-du-Loir, Azay-le-Rideau stretches over eight communes on the banks of the Indre and the Loire, close to where the rivers meet. A mere 148 acres, the terroir is mostly flinty clay, clay limestone and Aeolian sand mixed with clay, and whereas the Chenins are strikingly mineral with strong notes of quince and apricot, most of Azay’s production is rosé, produced by law with a minimum of 60% Grolleau, either vinified alone or blended with Gamay, Malbec and/or Cabernet Franc.

Domaine Marie Thibault

(Touraine Azay-le-Rideau)

“I grew up in the Loire Valley, but unlike many vignerons working in the Loire, I did not come from a winemaking family,” says Marie Thibault, adding, “But also unlike many of them, I have degrees in both biology and oenology.”

Marie Thibault began making wine in the early 2000s, working for a time with François Chidaine in Montlouis, where she fell in love with Chenin Blanc. In 2011, she founded her own nine acre estate on a single windy slope in Azay-le-Rideau, a lesser known commune of Touraine. She immediately converted to organics and has been certified with Ecocert since 2014. Among the natural elements in her vineyards is the flock of two dozen ewes that graze between the vine rows during the autumn; every ten days, they are penned inside a new hectare to keep the soil naturally fertile and the grass clipped.

Marie Thibault

“My vineyard is small, but the soils are extremely varied and as such, so are the grapes I grow. I work with Côt (Malbec), and have a special love for Gamay, Grolleau, Chenin and Sauvignon Blanc. Most of my vines are at least 50 years old. I compensate for small production by purchasing from organic estates nearby, especially those owned by my family.”

2 Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Les Grandes Vignes’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘Gamay’ ‘natural’ ($41)

2 Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Les Grandes Vignes’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘Gamay’ ‘natural’ ($41)

Thibault’s unique lens on Gamay is seen in this example produced from 50+ year-old vines she discovered growing adjacent to her plot on flinty silex soil. The vines were untrained and un-trellised, and harvest was exceptionally labor-intensive. She allows a 10-month maceration in order to shows off the Gamay’s savory side, with crisp rhubarb, earthy red berry notes and fine-grained, well-integrated tannins showcased.

3 Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Le Grolleau’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘natural’ ($89) 1.5 Liter

3 Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Le Grolleau’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘natural’ ($89) 1.5 Liter

A wine whose heritage is perfectly reflected in Thibault’s scant acres—Azay-le-Rideau is ground zero for Grolleau, first planted in early 19th century. ‘Le Grolleau’ is an ultra-fresh example made using Beaujolais-style carbonic maceration and held to a little over 10% abv, which solidly qualifies it as a ‘vin de soif.’ It is made using 60-year-old organic vines planted on hillsides on the southern slopes of the Indre—an early-ripening terroir filled with draining soils with a presence of flint, and bottled at the Estate in April 2022 without fining or filtration and just a micro-dose of sulfur. This wine is kept even fresher en magnum; it is fruity, juicy and velvety with sweet cranberry, blueberry, red plum, blueberry, cranberry, a touch of pepper with black cherry on the finish.

2 Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Premier Nez’, 2019 VdF Loire-Touraine Blanc ‘Chenin’ ‘natural’ ($42)

2 Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Premier Nez’, 2019 VdF Loire-Touraine Blanc ‘Chenin’ ‘natural’ ($42)

A dry, mineral driven Chenin from 40-year-old vines. The wine is spiced with dried orange peel, anise, a touch of pine resin and ripe pear.

Touraine-Chenonceaux

Incorporating 27 communes located on both sides of the Cher River between Tours and Selles-sur-Cher, Touraine-Chenonceaux boasts soils designed to produce spectacular Sauvignon Blanc—clay with flints (with or without a covering of sand) and alkaline clay from the tuffeau limestone ridges. These tend to be intensely aromatic wines with notes of white flowers, ripe citrus and tropical fruit, full-bodied and imbued with a lingering finish.

Red wines, made from Cabernet Franc and Côt, are distinctive and elegant and suggest notes of fruit compote, anise and menthol. Concentration is key, and yields in Touraine-Chenonceaux are limited to 60 hectoliters per hectare for white wines and 55 hectoliters per hectare for red wines. Vineyards are planted on slopes running east-west to benefit from the region’s ample sunshine.

Clos Roussely

(Touraine-Chenonceaux)

Clos Roussely was once a lowly outbuilding of the great fortification at Angé-sur-Cher and as it happens, its five-foot-thick tuffeau walls serve to insulate the winery as efficiently as they once held off Attila the Hun. Not only that, but the 250-year-old hand-dug caves beneath it are ideal for aging the remarkable wines of Vincent Roussely. The transition from barn to vignoble began in 1917, when Anatole Roussely became the first of four generations to dedicate his life to detail; Vincent Roussely, his great-grandson, today works this remarkable terroir—22 acres of clay and limestone peppered with pockets of silex.

“It was my childhood dream to work these soils,” says Roussely, who inherited the estate in 2001. “The terroir is ideal for Sauvignon Blanc, which makes up about 80% of our plantings, but at the heart of Roussely is a small plot of old-vine Gamay. We also have Côt (Malbec), Pineau d’Aunis and a little Cabernet Franc. We have always farmed organically, both for the health of the vines and out of social responsibility, but we were officially certified in 2007.”

Vincent Roussely

The old-school methodology runs through every aspect of the winemaking process. Grapes are hand-harvested and are subject to slow, natural fermentation in the cool catacombs; Gamay undergoes the familiar Méthode Beaujolais, partial carbonic maceration in which some whole grapes are kept intact and begin alcoholic fermentation within the confines of their skins.

Evolving from tradition to technology, Roussely continues to experiment, using concrete eggs for some of his fermentations. “Innovative adaptation means more than simply exploring new techniques,” he says. “It also involves a commitment to ecological responsibility. Right now, about 65% of Loire Valley vineyards are organic and it’s our goal to see that number at 100% by 2030.”

3 Clos Roussely, 2022 Touraine-Chenonceaux Blanc ($25)

3 Clos Roussely, 2022 Touraine-Chenonceaux Blanc ($25)

Made from 100% old-vine Sauvignon Blanc grown in organic vineyards, the wine emits a bouquet of white flowers, citrus and lemon curd with exotic tropical fruits to shore up a bracing acidity.

4 Clos Roussely ‘L’Escale’, 2023 Touraine Blanc ($20)

4 Clos Roussely ‘L’Escale’, 2023 Touraine Blanc ($20)

A Sancerre-styled Sauvignon Blanc minus the price tag, this wine shows grapefruit, lime and lots of tropical fruit with a long, mineral driven finish. Although ‘l’escale’ means ‘the stop over,’ this is a wine that invites you to linger while you’re there.

4 Clos Roussely ‘Canaille’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘Gamay’ ($17)

4 Clos Roussely ‘Canaille’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘Gamay’ ($17)

‘Canaille’ is the French word for ‘scoundrel.’ 100% Gamay from vines between 25 and 50 years old grown organically on clay and limestone. Aged six months in stainless steel, the old vines add a striking depth to this exuberant Gamay, replete with notes of crushed raspberry, black cherry and nutmeg.

Orange is the New Red

Orange wine is an interesting style subset whose popularity has grown in tandem with the natural wine movement, although even within that space, orange wine has a niche all its own. In the Loire (as elsewhere), red wine is made by leaving crushed grapes in contact with their skins as they ferment. White wine is generally made without skin contact during fermentation… unless it’s destined to be orange wine, which is (essentially) white-skinned grapes crushed and fermented on the skins, which imparts eye-catching amber, copper and often orange tints.

Orange wines offer a different sort of bridge between red and white wines than rosé; tannin is generally more obvious and flavors are, like many natural wines, an acquired taste which may be likened to hay, bruised apples, dried apricot, and yes, even orange peel.

5 Clos Roussely ‘Orange’, 2023 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘Sauvignon’ ($19)

5 Clos Roussely ‘Orange’, 2023 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘Sauvignon’ ($19)

Although winemakers and sommeliers are quick to point out that ‘orange’ refers to the color, this is another example of a skin-macerated Sauvignon Blanc that sends out vibes of orange pith along with apricot and earthy minerality. The wine is a painstaking labor of love, aged 6 months in stainless steel, neither yeasted, nor chaptalized, nor fined.

Cheverny & Cour-Cheverny

Around 40 Cheverny wine growers produce slightly under 3 million liters of red, white and rosé wines each year from 1500 acres of vineyards located in Cheverny itself and in 23 nearby parishes on the southern banks of the Loire. Reds are based on Gamay and Pinot Noir, while Cabernet Franc and Côt (the local name for Malbec) can play supporting roles. They are early-drinking wines best consumed within two years of vintage.

Whites are a combination of Sauvignon Blanc and Sauvignon Gris with lesser proportions of Chardonnay, Chenin and Arbois (here spelled ‘Orbois’) allowed. Although these wines have been compared to the Sauvignons of Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé, they lack the distinctive minerality and searing acidity that defines the eastern Loire’s two most-famous appellations.

Cour-Cheverny is a unique wine region located within the Cheverny appellation; it produces white wines made only from the rare grape variety Romorantin. Romorantin is an old Burgundian grape now only grown in Cour-Cheverny—wines are herbal, showing apple and pear behind Acacia flowers. They are also ripe for aging, and mature, Romorantin develops aromas of honey, lemon and beeswax.

Domaine Hervé Villemade

(Cheverny & Cour-Cheverny)

Hervé Villemade is where he belongs; at the helm of a family estate: “My grandparents founded the domain and I took over in 1995. At the time there were 8.5 hectares of rather young vines (15-20 years) that my grandparents had planted. The farm used to be in polyculture and the old vines from the 1960’s had been removed to plant new ones in the 1970’s. When I took over, I replanted five hectares and started renting some vines as well. I’ve also bought land over the years and today we find ourselves working 25 hectares—eight are mine, 8.5 are my parents’ and the rest is rented.”

Hervé Villemade

When Hervé first took the reins, the entire estate was farmed conventionally, with chemicals in the vineyards. Unaware of the alternatives, he followed in his parents’ footsteps until he became very bored with end results: “The wines were uninspired and bland,” he says. “Around this time I was introduced to wines that were different, that spoke to me, that struck a chord emotionally: Natural wines. Coincidentally, at the exact same time that I was discovering these wines I started developing a very serious allergy to sulfur. This was around 1997. My first attempt at sulfur free winemaking was two years later. What I hadn’t realized, and what I quickly found out (through Marcel Lapierre in particular), was that to make sulfur free wine, you needed clean grapes. From that point I immediately started converting the entire estate to organic agriculture and have worked this way ever since.”

6 Domaine Hervé Villemade ‘Les Ardilles’, 2022 Cheverny Rouge ($37)

6 Domaine Hervé Villemade ‘Les Ardilles’, 2022 Cheverny Rouge ($37)

85% Pinot Noir, 15% Gamay from sandy clay soils with silex over limestone—produced only in exceptional vintages. Maceration lasts 20 days with moderate punching down, following which the wine is aged in tuns, barrels, truncated conical vats and amphorae. Crunchy red fruit and balanced acidity display Villemade’s signature style—an extreme purity of fruit.

7 Domaine Hervé Villemade, 2022 Cheverny Rouge ($26)

7 Domaine Hervé Villemade, 2022 Cheverny Rouge ($26)

40% Gamay and 60% Pinot Noir macerated (80% whole-cluster and 20% destemmed) for 15 to 20 days. It is fermented and aged in concrete and wooden ‘tronconique’ vats without pump-overs, pigeage, racking or filtration. The wine shows bright red fruit, especially black cherry with and slightly spicy and glossy touches.

8 Domaine Hervé Villemade ‘Bovin’, 2022 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘Gamay’ ($28) 1 Liter

8 Domaine Hervé Villemade ‘Bovin’, 2022 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘Gamay’ ($28) 1 Liter

Hand-harvested, 100% Gamay from vines between 40 and 60 years old grown in the Cher Valley. The grapes are macerated for 10 days in concrete with intervention, then bottled using a minimum of sulfur for stability. The wine is ripe and crunchy with red fruit and displays the lighthearted ease that the label suggests.

9 Domaine Hervé Villemade, 2022 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘Gamay’ ($25)

9 Domaine Hervé Villemade, 2022 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘Gamay’ ($25)

100% Gamay from the Cher Valley, the wine is aged in wooden vats without human intervention until it is bottled without filtration. The wine shows aromas of red fruits, candied blackberries with a hint of cinnamon behind balanced mineral notes and a silky finish.

5 Domaine Hervé Villemade ‘La Bodice’, 2022 Cheverny Blanc ($38)

5 Domaine Hervé Villemade ‘La Bodice’, 2022 Cheverny Blanc ($38)

80% Sauvignon Blanc, 20% Chardonnay; La Bodice is a single vineyard wine that combines tropical fruit and herbaceous citrus.

6 Domaine Hervé Villemade ‘Les Acacias’, 2020 Cour-Cheverny Blanc ($50)

6 Domaine Hervé Villemade ‘Les Acacias’, 2020 Cour-Cheverny Blanc ($50)

100% Romorantin, aged 50% in amphorae and 50% in demi-muids for 23 months. It shows a luscious and complex nose filled with white flower along with touches of honey and five-spice powder. The palate echoes the nose, with a mineral backbone and hints of smoke.

Famille Percher

(Cheverny & Cour-Cheverny)

Perhaps the most interesting parcel farmed by Luc Percher (of Famille Percher) is ‘La Marigonnerie’ directly adjacent to the winery. In Napoleon times the vineyard area was a pond, and although the region sits on a bed of limestone sprinkled with granitic sand, the pond left behind a bed of clay which, about 120 years ago, was planted to Romorantin—a local white wine variety with its own appellation (Cour-Cheverny) where it is the only grape permitted.

Luc began making wine here in 2005. “When I arrived, the sand was as white as a beach. I fell in love with the ambience—a few wispy trees and an expansive horizon-line. It is quiet terroir.”

Luc Percher

His 22 acres of vines, tended with certifications from BIO and Déméter, is hardly restricted to Romorantin, although only his 100% Romorantin can be labeled Cour-Cheverny. His Sélection Massale old-vine vineyards contain ten different grape varieties, and some even more rare than Romorantin—Menu-Pineau, Gamay Fréaux and Chaudenay, for example. In order to maintain the biological heritage of these grapes, Luc is committed soil maintenance, through hilling, stripping, scratching and the establishment of controlled natural grassing. “These practices are respectful of the earth, the plants and the environment; they support the development of biodiversity and preserve the terroirs. You no longer see the white sand between the vine rows—it is covered by grass and other vegetation. We echo that philosophy in the cellar, being minimalist on the interventions in order to more faithfully reflect the grape varieties and the purity of place.”

10 Famille Percher, 2019 Cheverny Rouge ($36)

10 Famille Percher, 2019 Cheverny Rouge ($36)

A 50/50 blend of Pinot Noir and Gamay grown on sandy clay with a limestone base. It is fermented with indigenous years and spends 15 days macerating before élevage in stainless steel on fine lees. It shows a frisky nose of black cherries and cassis with an edge of earth—graphite, tree bark, espresso and forest floor. Tannins are moderate and the finish is long.

7 Famille Percher, 2019 Cheverny Blanc ($36)

7 Famille Percher, 2019 Cheverny Blanc ($36)

60% Sauvignon Blanc, 40% Menu Pineau from sandy, clay limestone soils. Fermentation is done on indigenous yeasts with élevage in stainless steel and bottled without fining or filtering. Menu Pineau is the local name for Arbois and in Cheverny produces wine characterized by low acidity, apple aromas and a delicate, mineral substructure.

8 Famille Percher, 2020 Cour-Cheverny Blanc ($46)

8 Famille Percher, 2020 Cour-Cheverny Blanc ($46)

You won’t experience many wines made from 120-year-old vines, but this one comes from Percher’s oldest parcel. 100% Romorantin showing a bouquet of honeysuckle and acacia and an intensely mineral-driven palate of pear, apple skins and honeycomb.

Le Petit Chambord

(Cheverny & Cour-Cheverny)

“The wines of François Cazin are wines of purity, minerality and a sweet-sour vibrancy that makes my mouth water for more. I have no doubt that he is one of the leading vignerons in the appellation, along with Michel Gendrier, Michel Quenouix, Laura Semeria and Christian Tessier, among one or two others. Indeed, I am sure there are some who would place him at the very top.”

François Cazin works with approximately 50 acres of vineyards; three-quarters in the Cheverny appellation, while the rest is are in the Cour-Cheverny appellation. As this latter appellation only amounts to about 125 acres in its entirety, François Cazin is cultivating about 10% of the entire appellation, where his Romorantin vines average over 30 years old.

In his Cheverny and Crémant-de-Loire acres he tends Pinot Noir, Gamay, Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay, as well as small parcels of Côt and Menu Pineau. The Gamay and Sauvignon Blanc tend to be planted on more sandy-clay soils, while clay and limestone is favored for Pinot Noir.

François Cazin, Le Petit Chambord

“Everything in my Cour-Cheverny vineyard has to be done manually because of solid coat of limestone directly underneath the superficial soil,” Cazin says, championing his old-school endeavors. “Some of these vines are older than my dad; they were planted by my grandfather. It goes without saying that these are 100% in Massale, and they are in better shape than the vast majority of my other vines. For example, the clonal selection on the other side of the house is much younger, but there is way more mortality.”

11 Le Petit Chambord ‘Vendanges Manuelles’, 2022 Cheverny Rouge ($23)

11 Le Petit Chambord ‘Vendanges Manuelles’, 2022 Cheverny Rouge ($23)

Pinot Noir/Gamay/Côt from estate vines averaging thirty years old and grown on clay-limestone soils. The Pinot Noir is destemmed and macerated for a week while the Gamay is whole-cluster fermented semi-carbonically; the small bit of darker, more tannic Côt (aka Malbec), adds a touch of color and structure.

9 Le Petit Chambord ‘Vendanges Manuelles’, 2023 Cheverny Rosé ($21)

9 Le Petit Chambord ‘Vendanges Manuelles’, 2023 Cheverny Rosé ($21)

A blend of Gamay and Pinot Noir, made with both direct-press and saignée methods; each parcel is vinified individually in stainless steel and élevage takes place in enamel-lined concrete tanks with pre-bottling blending.

10 Le Petit Chambord ‘Vendangé à la Main’, 2023 Cheverny Blanc ($22)

10 Le Petit Chambord ‘Vendangé à la Main’, 2023 Cheverny Blanc ($22)

82% Sauvignon Blanc,18% Chardonnay; the wine shows a nice balance of Chardonnay’s roundness and buttery fruity notes and fresh citrus notes of Sauvignon Blanc.

11 Le Petit Chambord ‘Vendanges Manuelles’, 2021 Cour-Cheverny Blanc ($24)

11 Le Petit Chambord ‘Vendanges Manuelles’, 2021 Cour-Cheverny Blanc ($24)

100% Romorantin from vines between 40 and 90 years old. The wine shows orange blossom, candle wax, pear and lemon peel.

12 Le Petit Chambord ‘Renaissance – Vendanges Manuelles’, 2020 Cour-Cheverny Blanc ‘Moelleux’ ($27)

12 Le Petit Chambord ‘Renaissance – Vendanges Manuelles’, 2020 Cour-Cheverny Blanc ‘Moelleux’ ($27)

‘Moelleux’ indicates sweetness, although it often highlights the fattiness inherent in the grapes. In this one, the harvest is direct pressed and fermented in stainless steel, then later, cold stabilized with an addition of sulfur to keep sugars in the wine and block fermentation. Élevage is done in 300-liter barrels for six months, then in underground vats until the following spring. It offers a symphony of apricot, honey and quince with a balanced acidity that lingers on the palate.

Notebook …

Vin-de-France (VdF): Should I Stay, or Should I Go?

Created in 2009 as a category of wine meant to encourage both experimentation and exploration, this label designation means only that the grapes were grown in France. The quality (or, perhaps, lack thereof) does not stem from its region of origin or a strict set of specifications, but in the freedom it offers winemakers and winegrowers to get their creative juices flowing.

By eschewing the rules and regulations of the location-based Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) or Indication Géographique Protégée (IGP), VdF allows innovation among winemakers who wish to grow varieties not permitted within their particular region and who relish to freedom to produce creative, boundary-pushing wines.

The plusses are obvious: Vin de France-labeled wines are generally much more affordable than their AOC counterparts, and may serve as entry points to an estate’s terroir-driven, higher-end selections without the matching price tags.

The downside (if any) is that the VdF designation is marketed directly at drinkers who are intimidated by the elaborate, geography-grounded system that many of us love and consider the defining feature of our fascination with the subject. Many Francophiles, both in the United States and abroad, believe that any major change to the French wine system meant merely to sell more bottles at the expense of tradition sort of misses the point of the entire artform.

- - -

Posted on 2024.07.25 in Touraine, Coteaux-du-Loir, Cheverny, Coteaux-du-Loir, Cour-Cheverny, Touraine Azay-le-Rideau, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Loire | Read more...

A Veritable Revolution in Sancerre: Stéphane Riffault is Creating Wines of Texture, That are Singular, and True to Themselves. (Seven-Bottle Pack $299: Two Red and Five White)

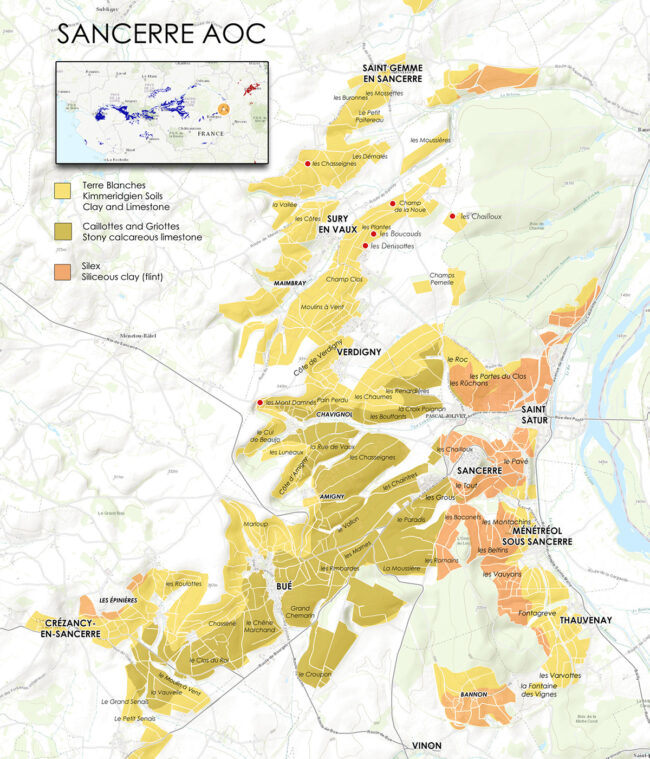

A communion with the soil is the most important relationship a winemaker will ever forge, and nowhere is this demonstrated more reliably than in Sancerre, where three distinct soil types produce a split-personality of wine characteristics. This may be something of well-kept secret, as the name ‘Sancerre’—even to experienced wine drinkers—often exists as a single, all-encompassing concept limited to crisp, bone-dry, citrus-scented Sauvignon Blancs.

Sancerre, as it happens, is a wealth of subtleties from commune to commune, vineyard to vineyard, lieu-dit to lieu-dit, just as it is in Burgundy.

In this week’s exploration, we’ll take a look at the portfolio of one of Sancerre’s most innovative young winemakers, Stéphane Riffault, owner of Domaine Claude Riffault, who works 33 different parcels and eight different lieux-dits spread across four villages. Riffault’s cross-section of Sancerrois splendor is a nice overview of the triumvirate of soils as well Stéphane’s mastery of balancing minerality and wood—a feat rarely duplicated anywhere else in the appellation.

Sancerre: Sauvignon Blanc is Only Part of The Story

Rumors that Sancerre is synonymous with Sauvignon Blanc have been greatly exaggerated. That said, no credible wine scholar will deny that the stars aligning between Sancerre’s terroir and the blonde scioness of the Val de Loire is a remarkable gift to us all. Just as the Loire River runs through the heart of France, Sancerre pierces the heart of summertime and Sauvignon Blanc grown among the brush, gravel and layers of Cretaceous soils provides an unadorned synthesis of the scents we associate with the easy season: Cut grass, Meyer lemon, tart hedgerow berries and petrichor—the incomparable aroma of raindrops on stone.

80% of the grapes grown in Sancerre are Sauvignon Blanc, so it is no wonder that this varietal dominates the market, especially in the United States. But nearly 20% is Pinot Noir, and it’s a fact that prior to phylloxera, Sancerre was best known for its red wines. Not only that, but in that not-so-distant past, the whites were rarely made from Sauvignon Blanc, but from Chasselas, which is still grown in small pockets.

When the diabolical little phylloxera louse decimated the vineyard of Sancerre (along with much of Europe) they were replanted with Sauvignon Blanc, which was more responsive to the requisite remedy—American root stock.

One thing did not change: The almost clichéd emphasis Sancerre places on purity. This is a result of two factors: First, the region is relatively far north, so a hallmark of nearly all Sancerre—red, white or pink—is its bright acidity—preserved in the grapes by cool nights and temperate days. The pH of a wine determines its mouthfeel, and the higher the acidity, the more sizzling is the sensation of freshness and clarity on the palate, often described as ‘purity.’

Of equal importance, very little oak is used in the maturation process of wines from Sancerre, and the flavors associated with oak—butter, clove, vanilla and caramel—however desirable in Burgundy—tend to mask some of the fruit-driven notes. It’s one of the reasons that oak-free Chablis is considered the purest incarnation of Chardonnay, and likewise, the neutral barrel or stainless steel/cement aging of Sancerre’s Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Noir and occasionally Gamay offers the best results for preserving the natural flavors inherent in the juice.

Soil Matters: Sancerrois Trilogy

Every cliché-driven wine writer on the planet will tell you that in order to make superb wine you must begin with superb grapes, and every conscientious winemaker on earth will tell you that to grow those grapes you need superb soil. And few appellations the size of Sancerre (roughly 7000 acres) are more narrowly defined by three unique variations on that theme, and this is a point of pride for Sancerre’s winegrowers.

First, are the silex soils, which extend southward from Saint-Satur to Thauvenay. Silex soils contain flint (‘silex’ is what the British call this sedimentary form of quartz); such soils form over millennia as limestone erodes to dust and much harder stones are left in its wake. Flint leaves an interesting imprint on Sauvignon Blanc; the wines are elegant and finely-etched with distinctive citrus and herbal notes, but most prominent is the spark/smoke character that the French call ‘pierre à fusil’—literally, gunflint. The smoky minerality that is so prized in tasting notes is far more evident in silex soils than those chalkier wines grown in limestone—silex wines attain a nearly indefinable quality of precision, like the edge of an arrowhead.

Next is the Kimmeridgian marl found on Sancerre’s westernmost hills (as well as in Chablis Grand Crus and many great Champagne terroirs). It is a mixture of limestone and clay that formed eons ago as the final resting place of the famous comma-shaped oyster, Exogyra virgula. Their fossilized shells (quite visible in many stones from the region) left the soils rich in calcium carbonate. Amazingly, wines from this prehistoric graveyard produce wines in which the now-evaporated sea—in the form of a briny undertow, or saltiness—can clearly be tasted. Kimmeridgian marl is known locally as ‘terres blanches’ because the chalky clay turns white in dry periods.

Sancerre’s Oxfordian limestone soils are perhaps less heralded but they are arguably more important because they produce the bulk of the ‘entry-level’ early-drinking Sancerres that—in the public perception—may better typify the region. That is not to say that, in the right hands, they cannot produce wines of great subtlety, as proven by Stéphane Riffault, whose Sury-en-Vaux estate sits (in part) on a ribbon of Oxfordian. These are stone-filled soils, but unlike silex soils, there’s little flint and unlike Kimmeridgian, there is little clay. Instead, the rocky subsurface is filled with two distinct types of stone, caillottes, which are sizable pebbles and Griottes, which are much smaller. Oxfordian limestone tends to run north-south from Sainte-Gemme down through Bué and below.

Domaine Claude Riffault

Le Métronome*

*From ‘Our 25 Domaines of the Year,’ Guides des Vins 2020, Bettane+Desseauve:

“When you think of Sancerre, you absolutely have to mention Stéphane Riffault. Measure, attention and reflection forge high-flying and stylish cuvées; each reflecting the personality of its terroir. Everything here exudes excellence.”

When Stéphane Riffault took over Domaine Claude Riffault from his father Claude, he brought with him a tool kit earned in a number of contrasting appellations, having studied and trained with Olivier Leflaive in Burgundy and at Château Angélus in Bordeaux. This broader view informed the core, hands-on education he received from his father at the domain. Among the rather ‘un-Sancerre-like’ methods he brought to the estate was hand-harvesting and extensive sorting before the crush; Stéphane’s wife Benedicte leads the harvest team while Stéphane manages the sorting and press during harvest.

Meanwhile, among the conclusions at which he arrived on his own is that sustainability is key to the future. As such, all 33 of his vineyard acres are organic (Ecocert, 2016) and biodynamic (Biodyvin, 2021).

Stéphane Riffault, Domaine Claude Riffault

All good winemakers seem to be equal parts dirt-farmer and metaphysical philosopher, and Stéphane is no exception: “Being a winegrower and winemaker demands commitment, risk and continual self-questioning,” he maintains. “You have to know how to adapt in order to stay dynamic. Improvement requires perpetual movement, and what drives me is the creation of wines of texture; wines that are singular and true to themselves.”

Although most of the Riffault’s holdings are planted on the soft limestone soil called ‘terres blanches’, he farms a handful of parcels on caillottes and silex; thus, he has developed a keen understanding of the qualities that each unique terroir brings to an individual wine. He employs oak moderately to add length to his already-precise, site-expressive and highly delineated bottlings.

All his parcels are vinified separately, and (except for the rosé), all are bottled unfiltered.

White Sancerre: Lieux-dits Tell Their Story

As someone trained in Burgundy (and whose brother Benoît is the winemaker at Domaine Etienne Sauzet in Puligny-Montrachet), you might expect Stéphane Riffault to have a particular affinity for lieux-dits—those unique parcels of vineyards so singular in expression that they have their own names. This is absolutely the case, and there is more: The Crus of Burgundy may be well-mapped and understood, but far less so are the vineyards and lieux-dits of Sancerre. Riffault considers them among France’s finest terroirs, able to produce great white wines not of stature and complexity, but of individual identity. As such, he is making it his mission to champion eight parcels among the 33 plots he currently works as part of an exacting showcase stratospheric Sancerres seen from a near-microscopic perspective.

Domaine Claude Riffault, 2022 Sancerre ‘Les Denisottes’ Blanc ($49)

Domaine Claude Riffault, 2022 Sancerre ‘Les Denisottes’ Blanc ($49)

Les Denisottes is a three-acre plot located near Riffault’s Sury-en-Vaux estate and is composed of three individual southeast-facing plots at nearly a thousand feet in altitude. The vines (between 40 and 50 years old) are rooted in deep Kimmeridgian limestone. The juice fermented spontaneously and was aged on lees for 14 months in multi-layer wooden barrels with sporadic bâtonnage and no malolactic fermentation, producing a wine loaded with citrus zest, green apple tartness and a distinct flinty minerality.

Domaine Claude Riffault, 2022 Sancerre ‘Les Chailloux’ Blanc ($49)

Domaine Claude Riffault, 2022 Sancerre ‘Les Chailloux’ Blanc ($49)

Les Chailloux is a unique site in the village of Sury-en-Vaux. While silex soils are common in the neighboring Pouilly-Fumé and the eastern edge of Sancerre, it is fairly scarce in the northwestern part of Sancerre. Stéphane Riffault farms about three acres of vines in this lieu-dit, which produces concentrated and opulent wine, yet racy and intensely saline and capable of aging gracefully for many years.

Domaine Claude Riffault, 2022 Sancerre ‘Les Chasseignes’ Blanc ($44)

Domaine Claude Riffault, 2022 Sancerre ‘Les Chasseignes’ Blanc ($44)

Les Chasseignes is an east/southeast facing lieu-dit that sits at nearly 900 feet in altitude. Planted on gravelly limestone soils, the wine opens with a greenish, refreshing bouquet and gains considerably in complexity upon aeration, becoming round and elegant and finishing with savory notes.

Domaine Claude Riffault, 2022 Sancerre ‘Les Boucauds’ Blanc ($40)

Domaine Claude Riffault, 2022 Sancerre ‘Les Boucauds’ Blanc ($40)

From a top parcel in Sury-en-Vaux; the 2022 Boucauds is a blend of both Burgundy barrels (several from Etienne Sauzet in Puligny-Montrachet) and larger oak formats. Because of the deep clay and limestone soils, Les Boucauds always has great mouthfeel and depth, as opposed to Stéphane’s silex and caillottes parcels which are more linear and austere in their youth. Sourced from several Les Boucauds plots, this cuvée employs close to half of all the Sauvignon Blanc planted on the estate.

Domaine Claude Riffault ‘Mosaïque Calcaire’, 2022 Sancerre Blanc ($39)

Domaine Claude Riffault ‘Mosaïque Calcaire’, 2022 Sancerre Blanc ($39)

In 2018 Stéphane Riffault made the decision to release a village-level Sancerre after additional plantings on limestone terroirs that he has undertaken over the last decade. It also includes some fruit from Les Boucauds and Les Chasseignes along with eighteen other parcels. Like all good Sancerre, this wine is supple and nearly succulent, filled with tropical notes besides the melon and pear foundation. It is rich, but remains light on its feet behind gentle acidity.

Red Sancerre: Taking Cues from Burgundy

To look for a silver lining amid the global catastrophe of climate change is nearly sacrilegious—unless you are a fan of red wine from Sancerre. Despite its strong history in the appellation, red wine grapes (Pinot Noir, almost exclusively) once struggled to ripen, and when they did, did so erratically. In all but exceptional vintages, Sancerre reds had a reputation for being thin and somewhat weedy, and even the alchemy of elite producers like Domaine Claude Riffault tended to produce wines with obvious bell pepper notes—a telltale signature of under-ripe red grapes, and an issue that oak does not fix.

In 2014, a warming climate began to put some of these nagging problems in the rearview mirror. The growing season was not necessarily longer, but the diurnal temperature shifts—vital for maintaining a useable balance between sugars and acids—allowed Pinot Noir to ripen more completely and more evenly. The wisest producers began to rely on a Burgundian approach; vinifying individual parcels by terroir, relying on blends that may vary from year to year, and perhaps most importantly, rethinking the use of oak barrels, allowing them to accent rather than submerge the fruit.

And every year, the fruit is proving itself reliably worthy, showing the rich black cherry and cola notes lifted by acidity that we have come to expect in top Burgundies.

All this does not meliorate the downside of climate change, but if life hands you lemons, might as well become better acquainted with Sancerre’s now world-class Pinot Noirs.

Domaine Claude Riffault, 2019 Sancerre ‘La Noue’ Rouge ($38)

Domaine Claude Riffault, 2019 Sancerre ‘La Noue’ Rouge ($38)

La Noue is a six-acre plot of Pinot Noir on planted on Kimmeridge limestone, and here, Riffault’s Burgundian-trained touch is evident. The enticing tea like, garrigue-infused fragrance is followed by raspberry, blueberry and violet notes enrobed in silky tannins. As with all wines from Domaine Claude Riffault, the vines are cultivated according to organic and biodynamic guidelines. Manual harvesting is followed by 18 months of ageing. Total production amounts to 10,630 bottles.

Domaine Claude Riffault ‘M.T. Mise Tardive’, 2019 Sancerre ‘La Noue’ Rouge ($48)

Domaine Claude Riffault ‘M.T. Mise Tardive’, 2019 Sancerre ‘La Noue’ Rouge ($48)

‘Mise Tardive’ refers to a process in which the unbottled wine undergoes a longer élevage with extended lees aging. Divided into seven plots and ranging in age from 10 to 60 years old, Noue is the source for both Noue Rosé and Rouge. Stéphane’s Rouge shows his Burgundian-trained touch with this variety, one that preserves the light and delicate style of Pinot from Sancerre, but layered with a depth of red fruit and black tea flavors.

RECENT ARRIVAL

Chavignol’s Damned Mountain: The Geography of Sancerre Writ Large

Mohammed was a teetotaler, but if he’d been a Sancerre lover and he had to go to the mountain, it would have been Chavignol. With apologies to Francis Bacon, who came up with the proverb about Mohammed and mountains in 1625, Chavignol looms above Sancerre as a Kimmeridgian limestone and marl billboard for the heights that this wine can reach.

It’s notable that in Sancerre (unlike the Médoc and Burgundy), the appellation system has no officially designated Premier Cru or Grand cru vineyards, based in part on a local reluctance to emphasize individual hamlets or specific lieux-dits sites that might divert consumers from the easily identifiable Sancerre brand. Chavignol remains an exception to prove the rule: Inhabitants of this eponymous village have long marketed wine under the name ‘Chavignol,’ and still mention it on the labels of their Appellation Contrôlée Sancerre wines. This is not simply the obligatory inclusion of their address, but a subtitle which takes on such dimensions that the name of Sancerre is eclipsed.

Located just a few minutes’ drive to the west of Sancerre, Chavignol is home to two of the appellation’s most famed lieux-dits, Les Monts Damnés and Le Cul de Beaujeu, which are together responsible for some of the region’s most sought-after wines.

Domaine Thomas-Labaille

Claude Thomas continued to work old vines in Monts Damnés—Sancerre’s greatest vineyard site—until well into his seventies, just as he maintained his standards in the cellar with élevage in old foudres and unfiltered bottlings. He clung to traditions in the hope that his daughter and son-in-law would ultimately take the reins.

This finally happened when Jean-Paul Labaille quit his civil servant job and became a full-time vigneron—although for the previous ten vintages, he had taken his vacation during the harvest to be the assistant winemaker to Claude Thomas. Few changes have happened under the new guard, and the 27 acres of vineyards remain among the best in Chavignol, with a large proportion of old vines. The oldest barrels have been re-placed by newer, mostly second-hand barrels that are 2 to 3 years old. The goal at Thomas-Labaille has always been to avoid any oaky character, but to let the wine breathe as it evolves slowly on its lees.

Jean-Paul Labaille, Domaine Thomas-Labaille

Work in the vineyards still follows Claude Thomas’ time-honored techniques, though through necessity as much as through respect: Monts Damnés is too steep a slope to ever consider machine harvesting—now the norm in the appellation—but the site is so spectacular that it’s worth the trouble. Many of the vines are over 80 years old; a genuine rarity in Sancerre. Given such spectacular raw material it’s no wonder that the resulting wine remains sensational: Rich, fat, round, with layered aromas, and marathon finishes. These are not a typical bistro Sancerres, but graceful wines meant for aging.

Domaine Thomas-Labaille, 2022 Sancerre – Chavignol ‘Les Monts Damnés’ ($46)

Domaine Thomas-Labaille, 2022 Sancerre – Chavignol ‘Les Monts Damnés’ ($46)

100% Sauvignon Blanc fermented on native yeasts in fiberglass and cement, then aged on lees in stainless steel tanks (with a small proportion of old barrels in some vintages) for four to six months and bottled without filtration. The nose shows a bit of citrus and nectarine with hints of guava; the palate is weighted and luscious, and the wine finishes with a delineation and minerality reminiscent of a top Chablis, a hallmark quality of Monts Damnés.

Domaine Thomas-Labaille ‘Cuvée L’Authentique’, 2023 Sancerre Rosé ($30)

Domaine Thomas-Labaille ‘Cuvée L’Authentique’, 2023 Sancerre Rosé ($30)

Jean-Paul also makes a younger, fresher wine that is released earlier than Monts Damnés and is meant for immediate consumption. Formerly bottled as straight ‘Sancerre,’ for the past few vintages, it has been labeled as ‘Cuvée l’Authentique.’ This wine is sourced from all the estates’ vineyards, and shows high-toned citrus fresh grasses and forest floor but is dominated by its stoniness.

Vintage Journal in Centre-Loire

The 2022 Vintage

Directly from the journal of Jean-Paul Labaille:

“Following the terrible frost that impacted our crop in 2021, it almost feels like 2022 was blessed from above. While it’s true that drought and hail impacted many vineyards this year and that the heavy rainfalls in June made it very challenging to work the soils, in the end the vines were balanced and we did not suffer the same amount of hydric stress felt by so many other regions. We even had some light rain in August and at the very beginning of harvest, giving us grapes of great quantity and quality. We began on September 5th, interrupted once on the 7th by a hail storm that touched the Northwest of the appellation. In Chavignol there were zero impacts. Qualitatively, we are in for a good vintage. The fermentations have been going well, with pH levels between 3.2 and 3.3, permitting us to keep a good amount of freshness. The alcohol will end up between 12.5 and 13.5, maybe as high at 13.7 on the Monts-Damnés. 2022 really reminds me of 2018, which is very promising!”

The 2020 Vintage

Temperatures in Central Loire began to warm up in the second half of February, setting the stage for the season and giving the vines an early start. In mid-March to mid-April cold nights caused some vignerons to us mobile anti-freeze towers and light braziers to warm the vines, and in the end, there was very little frost damage. Flowering went very well and thanks to dry weather there was virtually no mildew. But this dryness became a concern during the summer and blocked the ripening process in mid-August. Rain finally arrived at the end of August which allowed the vines to start producing again, reducing the gap time between phenolic and physiological maturities. The harvest took place in sunny dry weather and the vintage achieved both quantity and quality.

The 2019 & 2018 Vintages: The Twin Years

The back-to-back vintages 2018 and 2019 represent something of a climactic miracle. Even as a stand-alone, 2018 is considered to be one of the most exceptional vintages seen in the region for half a century. Taken together with a spectacular 2019, they are twin towers of triumph.

2018 began with fantastic spring that allowed for successful flowering and fruit set without any of the usual problems that normally occur with rain, hail or frost, and a hot summer developed the ripe semi-tropical flavors associated with the best Sauvignon Blanc. 2019 was a bit cooler, but produced grapes where the coveted acids that reign in aggressive fruit notes.

Tapping the source directly, Vacheron comments, “2018 and 2019 are very similar in the way they are constructed, even if the alcohol is slightly higher in 2018. The two vintages tend to show that it is possible to make wines that have good freshness despite low acidities because the minerality superseded the acidity. 2018 is without a doubt a vintage that will mark people’s memories, and will remain a reference in Sancerre. It’s the kind of vintage that helps grow a heightened generation of wine makers within their appellations.”

Notebook …

Wine Siblings: Sancerre and Chablis

Brothers from another mother or sisters from another mister; either way, the land beneath Sancerre and Chablis springs from the same prehistory. Classified in the middle of the 18th century by French geologist Alcide d’Obigny while he was working near the English town of Kimmeridge, he identified a unique layer of dark marl and called it ‘Kimmeridgian.’

Still, as in siblings, there are distinct differences in the DNA of English Kimmeridgian and French Kimmeridgian. The French layer is a relatively uniform chalky marl with thin limestone containing rich layers of seashells. This is because strata formed from the post Jurassic period continued to be deposited in the shallow sea areas which once covered part of France. The way these layers interact is key to the reason that French Kimmeridgian soils produce some of the world’s most heralded wine. The marly soil provides good structure, ideal water-retention and is easy to cultivate while hard limestone Portlandian contains numerous fossil fragments and, having been repeatedly shattered by frost, offers good aeration and ideal drainage along gentle slopes.

Chablis is a significant part of the Kimmeridgian chain; mid-slope vineyards in Chablis match almost perfectly to the Kimmeridgian outcrop, with the soft, carbonate-rich rock being covered by Portlandian limestone and supported by other limestone deposits. Sancerre, meanwhile, sits on top a fault ridge; the eastern side has a layer of Cretaceous soils while the west side is covered with brush and gravel slopes. Further west the best vineyards sit on the classic Portlandian-Kimmeridgian soil combination, producing a classic example of ‘terroir’.

- - -

Posted on 2024.07.20 in Sancerre, Rosé de Loire, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Loire | Read more...

The French Climate Divide: 2023 Rosés Show The Difference Between Warm-Climate (Mediterranean) and Cool-Climate (Oceanic) Fruit. Ten Types, Spanning the Two, by Seventeen Producers. A Dozen Rosés $349 – A Holiday Sampler.

Two things that France and the United States share: A red, white and blue flag and a passion for rosé. So, while we’re celebrating both on the Fourth of July, we’ll take the opportunity to offer a springboard to this style via through a series of rosés that span France from north to south.

Tastes in wine run hot and cold and so do the climates that produce them. Nearly every commercial vine on earth is grown between 30° – 50° latitude (both north and south), but that range offers an almost endless array of rainfall patterns, cloud covers and wind configurations and such a wide spectrum of environments and that generalization seems pointless. And yet, anyone qualified to blind taste with authority should be able to tell you very quickly whether the wine comes from cool or warm region simply by gauging the character of the fruit.

In cool climates, where budding occurs late and frosts arrive early, even grapes harvested at optimal ripeness tend to produce lighter, more acidic wines with flavor profiles that lean toward savory herbs and acidic fruits like cranberries and tart cherries. In fact, you’ll find these types of descriptors used for wines made from any number of varieties that have adapted to cooler climates. In contrast, warm weather and extended growing seasons in the world’s southerly vineyards results in jammier, richer wines with less acidity and darker fruit flavors (blackberry and plum), often underscored with exotic aromatics like coffee and chocolate.

Nowhere is this climate divide more obvious than in France, and no style of wine demonstrates it better than French rosé, a wine with many guises. A versatile food wine and a cherished part of French viticulture, crisp, cheerful rosé is produced both in France’s frosty north and sultry south with characteristically different, yet equally spectacular results.

Mediterranean Climate

Provence and Southern Rhône Valley Rosé

With the same passion as its red and white cousins, rosé raises the flag of diversity and complexity in an infinite combination of terroir, grape variety and vintage variation. If you still consider it a pale, pink, lightly alcoholic swimming-pool tipple, have we got a surprise for you!

Hugging the Mediterranean between Spain and Italy and blessed with consistently fine growing condition, Southern France produces wines ideally suited for this summery milieu. Despite its location France, the vineyards are still far north of almost all of Spain and Italy’s, so the days are long during the growing season, allowing grapes to fully ripen. The Gulf Stream and Mediterranean Sea keep it balmy while steady winds banish humidity that can cause disease and mildew.

As such, the reds are particularly robust, and these grapes, of course, are the foundation of the pinks.

The 2023 Vintage

Drought was the name of the 2023 game, and the Mediterranean coast experienced it badly, sometimes halving harvest volumes. Although vines can survive scorching heat, they tend to produce less juicy and more acidic grapes. But every region has its variations. The vines in Roussillon, for example, suffered severe water stress throughout the season whereas those in Languedoc experienced an ‘episode cévenol’—a storm specific to the south of France—in September. Despite these extreme conditions, the vines’ tough, deep roots were able to draw on unexpected resources to ensure that the grapes continued to grow and the overall harvest, while smaller than normal, looks promising.

Côtes-de-Provence

The massive Côtes-de-Provence sprawls over 50,000 acres and incorporates a patchwork of terroirs, each with its own geological and climatic personality. The northwest portion is built from alternating sub-alpine hills and erosion-sculpted limestone ridges while to the east, and facing the sea, are the volcanic Maures and Tanneron mountains. The majority of Provençal vineyards are turned over to rosé production, which it has been making since 600 B.C. when the Ancient Greeks founded Marseille.

Château Les Mesclances

Côtes-de-Provence

In the Provençal dialect, ‘Mesclances’ refers to the confluence of rivers, and the estate, a mere two miles from the sea in the commune of La Crau, is situated between two streams, the Réal Martin and Gapeau, which originate in the limestone massif of the Sainte Baume. The property consists of 75 contiguous acres and is a picturesque ideal of Mediterranean culture and pretty rolling topography. And certainly, this geography determines appellation status: Wines from the estate’s plain are IGP Méditerranée while the foot of the slope yields AOP Côtes de Provence, and the steeper incline of the hill carries the rare Appellation Côtes de Provence ‘La Londe’. Only 20 estates count La Londe in their holdings.

Mesclances is owned by Arnaud de Villeneuve Bargemon, whose family has run the domain since the French revolution. In April 2018, Alexandre Le Corguillé joined the team as estate manager, and as is to be expected, most of the vineyard production is dedicated to rosé.

1 Château Les Mesclances ‘Faustine’, 2023 Côtes-de-Provence ‘La Londe’ Rosé ($36)

1 Château Les Mesclances ‘Faustine’, 2023 Côtes-de-Provence ‘La Londe’ Rosé ($36)

La Londe is a tiny sub-appellation of the Côtes-de-Provence spread between the communes of Hyères and La Londe-les Maures itself, as well as some specific areas of Bormes-les-Mimosas and La Crau. 75% of the production is rosé made from Cinsault and Grenache, bolstered by up to 20% of various red and white varieties, including Tibouren, Syrah, Mourvèdre and Vermentino, known locally as Rolle.

Mesclances’ La Lond is a serious, age-worthy rosé that blends 90% Grenache and 10% Mourvèdre from the estate’s blue-schist soils, fermented spontaneously, with the Grenache given 15 hours of maceration and the Mourvèdre derived from the saignée method.

Bandol

Conventional wisdom has taught us that wine grapes fare best in places where nothing else will grow; rocky, water-starved soil on precipitous hillsides make vine roots work harder, ramifying and branching off in a search of nutrients and, in consequence, producing small grapes loaded with character. Cue Bandol, the sea-and-sun-kissed region along the French Riviera, which is not only good country for grapes, it’s good country for the soul. Made up of eight wine-loving communes surrounding a cozy fishing village, Bandol breaks the Provençal mold by producing red wines that not only outstrip the region’s legendary rosé, but make up the majority of the appellation’s output. In part that’s due to the ability of Bandol vignerons to push Mourvèdre—generally treated as a blending grape in the Côtes du Rhône and Châteauneuf-du-Pape —to superlative new heights.

Domaine La Bastide Blanche

Bandol

Michel and Louis Bronzo purchased Bastide Blanche in the ‘70s in the belief that the terroir could produce a wine to rival those of Châteauneuf-du-Pape. With that in mind, the brothers planted Carignane, Cinsault, Clairette, Grenache, Mourvèdre and Syrah. Vintage 1993 proved to be their breakaway year, putting both Bandol and themselves on the wine map.

The estate is located in the foothills of Sainte-Baume Mountain, five miles from the Mediterranean Sea on land that is primarily limestone scree.

2 Domaine La Bastide Blanche, 2023 Bandol Rosé ($31)

2 Domaine La Bastide Blanche, 2023 Bandol Rosé ($31)

Predominantly Mourvèdre shored up with Grenache and Cinsault, this cuvée is full-bodied from direct-press and shows orange citrus, watermelon, herbed cherry and some lengthy minerality.

Cassis

The entire vineyard area of Cassis is under five hundred acres, but most of the properties overlook the sea, which moderates the heat and creates an ideal climate for vine growing; the commune is known primarily for its herb-scented white wines, principally from Clairette and Marsanne (about 30% of Cassis production is rosé) and despite its name, it does not produce Crème de Cassis.

Domaine Bagnol

Cassis Rosé

Sitting just beneath the imposing limestone outcropping of Cap Canaille 700 feet from the shores of the Mediterranean, Domaine du Bagnol is the beneficiary of the cooling winds from the north and northwest and as well as the gentle sea breezes that waft ashore. Cassis native Jean-Louis Genovesi and his son Sébastien run the 18-acre estate.

3 Domaine Bagnol, 2023 Cassis Rosé ($37)

3 Domaine Bagnol, 2023 Cassis Rosé ($37)

45% Grenache, 35% Cinsault and 20% Mourvèdre. A taut, acidic, sea-dominated rosé from a handful of parcels totaling 17 acres planted in clay and limestone on a gentle north-northwest-facing slope. It shows the characteristic salinity of a coastal vineyard with supple nectarine and melon notes.

Côtes-du-Rhône

Côtes-du-Rhône is one of the largest single appellation regions in the world, covering millions of acres and producing millions of bottles of wine of varying degrees of quality. In Southern Rhône, it encompasses the majority of vineyards and includes hallowed names like Gigondas, Vacqueyras and Châteauneuf-du-Pape.

The latter wines prefer to use their individual, highly specific ‘Cru’ names, but the truth is, many generic Côtes du Rhônes may come from plots just outside official ‘Villages’ boundaries—some only across the road or a few vine rows away from top vineyards—and among them, you can find wines with nearly the same level of richness at a fraction of the cost.

Domaine Charvin

Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé

Established in 1851, Domaine Charvin is one of the region’s perennial superstars. Laurent is the sixth-generation Charvin to run the domain, and the first to commercially market a proprietary bottling. He tends vines in the northwest end of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, primarily in Cabrières, Maucoil and Mont Redon, farming organically and engaging in old-school vinification, without de-stemming and fermenting in concrete tanks for 21 months before bottling without filtration.

4 Domaine Charvin, 2023 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($24)

4 Domaine Charvin, 2023 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($24)

45% Grenache, 45% Cinsault, 10% Mourvèdre showing up-front notes of candied cherries, strawberry, lavender and Provençal herbs.

Oceanic Climate

Loire Valley Rosé

Established in 1974, Rosé de Loire is an official appellation that covers rosé made in the Loire Valley region of western France. Broadly speaking, the appellation follows the wider Loire River valley from Blois in the east, almost to Nantes, on the Atlantic coast in the west, covering the same lands as Touraine, Saumur and Anjou but stopping on the border with Muscadet.

Obviously, such a wide swath of land is varied in terrain and geography, from the shale-based vineyards in Anjou to the undulating chalk and tuffeau hills of Saumur and Vouvray. Touraine itself boasts a wide variety of soil types (including clay-limestone, clay-flint, as well as sand or light gravel on tuffeau. Climatically, the region is heavily influenced by water, with the Loire River and its tributaries moderating both very warm and very cold weather while the Atlantic Ocean (Bay of Biscay) to the west is the origin of much of the weather patterns in the area.

Only Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Gamay, Grolleau, Grolleau Gris, Pineau d’Aunis and Pinot Noir are permitted in Rosé de Loire wines. The blend (or single variety) used is at the discretion of the winemaker.

The 2023 Vintage

The Loire suffered a hit-and-miss 2023. The winter was relatively mild and rolled into an equally benign spring without cataclysmic frost. Budburst was largely successful, and the gently rising temperatures proved idyllic for flowering, with yields promising to be high. June, however, hot and humid and aggravated by frequent rain; disease pressure ran high. Producers had to frequently spray and those who weren’t vigilant lost yields. That said, the heat pushed the grapes to phenolic ripeness signaling an early harvest.

Although some parts of the valley were struck by several fierce heatwaves, nights were cool enough to preserve both acidity and aromatics.

Sancerre

Sancerre in a nutshell—or rather, an oyster shell—boils down to the sea. Sancerre’s terroir is built on the remnants of the vast primordial ocean that once covered the hills and valleys of northern France and deposited calcium-rich shells from ancient, oyster-like sea creatures. This is ideal soil for the two grapes for which Sancerre is justly famous, primarily Sauvignon Blanc and to a slightly lesser extent, making up about 20% of the output, Pinot Noir and its attendant rosé.

A ‘typical’ rosé from Sancerre is created by allowing the Pinot Noir to macerate on the skins for a short period of time, generally between two and 20 hours, lacing the wine with a deeply layered nose featuring elegant green citrus, sweet floral notes, passion fruit and fresh green herbs. A semi-tannic structure, which is prized in these rosés, usually means they are better after a year or two in the bottle.

Like its red-blooded parent, rosé made from Pinot Noir has a natural affinity for food, and is a perfect foil for the rich cheese produced throughout the appellation.

Domaine Pascal & Nicolas Reverdy

Sancerre Rosé

The oyster-shell limestone of Sancerre, called Kimmeridgian, forms the base soil beneath the tiny hamlet of Maimbray, located in a valley surrounded by chalk hills of Chavignol and Verdigny. Across 43 acres of this vital terroir, Pascal Reverdy and his wife Nathalie (alongside Nicolas’s widow Sophie) combine tradition with trajectory: Now, sons Victorien and Benjamin shore up the team. Having completed his DNO at Dijon, with stints at Armand Rousseau (Gevrey-Chambertin), Châteaux Léoville Las Cases and Beychevelle (St Julien) and Christine Vernay (Condrieu), Victorien returned first in 2019. Benjamin reappeared in the summer 2023, having cut his teeth at Domaine de la Romanée Conti.

Pascal, who founded the winery in 1993, explains the family’s mandate: “We are about 70% planted with Sauvignon Blanc and 30% with Pinot Noir. Hard pruning keeps yields low, with vineyard being grassed through, and lutte raisonnée being practiced. Harvesting is by hand and we have built a reputation across white, red and rosé Sancerres, with no oak ageing, as well as three special cuvées (Les Anges Lots, La Grande Rue and à Nicolas) which are barrel aged.”

5 Domaine Pascal & Nicolas Reverdy ‘Terre de Maimbray’, 2023 Reverdy Sancerre Rosé ($32)

5 Domaine Pascal & Nicolas Reverdy ‘Terre de Maimbray’, 2023 Reverdy Sancerre Rosé ($32)

The ‘Terre’ in the name is ‘blanche’—the ‘white earth’ of Sancerre’s classic terroir. From three acres of 30-year-old Pinot Noir grown in characteristic clay-limestone, direct-pressed and vinified in demi-muids (10%) and stainless steel tanks (90%), the wine shows a bouquet of ripe strawberries and red grapefruit underpinned by earthy tones that still allows bright acidity to sparkle through.

Domaine Roger & Christophe Moreux

Sancerre Rosé

Established in 1895, with winegrower roots extending back to the 16th century, work in the Moreaux’s 22 acres has been handed down across many generations. Today, following the retirement of his father Roger, responsibility rests with Christophe Moreaux.

Located in the tiny hamlet of Chavignol (population 200) along the Upper Loire River where they are renowned equally for their wine and their cheese—Crottin de Chavignol has its own appellation. Wine, however, is the passion of Christophe, who says, “We believe we are in possession of some of Sancerre’s greatest terroirs, the vineyards of Les Monts Damnés and Les Bouffants.”

Moreaux production is a scant 65,000 bottles per year, with about one quarter of it made from Pinot Noir, both red and rosé; it is fermented in stainless steel and aged for six to eight months before release.

6 Domaine Roger & Christophe Moreux ‘Cuvée des Lys’, 2023 Sancerre Rosé ($27)

6 Domaine Roger & Christophe Moreux ‘Cuvée des Lys’, 2023 Sancerre Rosé ($27)

A lightly structured rosé with a distinct herbal edge; ripe with aromas of apricots, cherries, currants, and wild strawberries supported by vibrant acidity.

Domaine Pierre Morin

Sancerre Rosé

Gérard Morin took over the family’s vineyards about twenty years ago and, while making some of the most striking wines in Sancerre, he prepared his son Pierre to run the show. Pierre, who once worked the vineyards of Adelaide Hills, saw little in Australia worth emulating in Sancerre. He now helms the estate with an eye toward maintaining a house style typical of Bué (about a mile and a half from the village of Sancerre): rich, aromatic whites and some particularly deep reds that are best matched, according to Pierre, to “an andouillette cooked in the vineyard on vine prunings, ideally for breakfast.”

The Morin’s vines are planted on a steep hard-calcaire amphitheater surrounding the commune of Bué and consist of 17 acres of Sauvignon Blanc and five of Pinot Noir. Yields are held low through spring de-budding (one of Pierre’s few, but significant changes) and all harvesting is done by hand. Fermentation is done by parcel in an air-conditioned chai, in enameled steel vats, with the finished wines left alone on their lees for as long as possible.

7 Domaine Pierre Morin, 2023 Sancerre Rosé – Bué ‘Les Rimbardes’ ($31)

7 Domaine Pierre Morin, 2023 Sancerre Rosé – Bué ‘Les Rimbardes’ ($31)

Les Rimbardes is situated to the east of Bué, nearly to the border of Sancerre. Soils here are heavy with clay, giving the wines more heft. This fruit-forward rosé offers grapefruit, strawberry, Meyer lemon, and tangerine zest aromas intertwined with rhubarb, lemon and hints of caramel.

Domaine Dominique et Janine Crochet

Sancerre Rosé

The steeps slopes of Bué are also home to winemakers Teddy and Cyprien Crochet, who took over from their father Dominique after his untimely passing. Although Teddy spent time as a rugby player, he remains true to his roots, now five generations deep. Cyprien raves about the holdings in Chêne Marchand, Grand Chemarin, Champ Chêne and the steepest vineyards in the La Côte de Bué: “We like to think that the Crochet name is synonymous with the town of Bué,” Cyprien says, “…one of the three greatest villages in Sancerre. We’re equally proud to be producing Sancerre in a winery our father started in a garage—we are true garagistes making ‘vins de garage.’”

Established in 1992, Dominique and Janine began with a handful of of perfectly situated hillside acres. Today, the domaine extends to nearly forty acres hosting more than forty tiny parcels. Grapes are hand-harvested—a Bué necessity, given the steep hillsides—and indigenous yeast is preferred, especially for the reds, which are treated to light clay filtration before bottling

8 Domaine Dominique et Janine Crochet, 2023 Sancerre Rosé ($29)

8 Domaine Dominique et Janine Crochet, 2023 Sancerre Rosé ($29)

Grown on silex soils, the wine is attractive in both color and bouquet; salmon pink and perfumed with cherry and rose petal, which is echoed on the palate with juicy citrus accents and culminates in an energetic and crisp finish.

Domaine de Sacy

Sancerre Rosé

In keeping with the theme of these selections—small production, family-owned hamlet wines—miniscule Sacy nestles near Crézancy and Bué; Karine Millet has taken over the family domaine with of vines. Karine practices polyculture, the historical practice in Sancerre, where cow manure from the farm is used throughout the vineyards and sustainable viticulture, without herbicide or pesticide, is the rule of the day. Her vines average 30 years old, with some approaching half a century.

“Our soil is all ‘terres blanche,’” Karine says. “This is a late-ripening terroir made of thick clay layers intertwined with flat, white limestone. It’s rich in fossils that have the particularity of whitening while drying in the sun. Terres Blanches terroir gives a strong aromatic concentration, tension and aging potential to the wines as well as a pronounced mineral character.”

9 Domaine de Sacy, 2023 Sancerre Rosé ($29)

9 Domaine de Sacy, 2023 Sancerre Rosé ($29)

A beautiful and balanced summer wine offering medley of citrus flavors wrapped in an with an intense bouquet of strawberry, raspberry and red fruit cake. The palate shows solid Sancerre structure with varietal character: spicy red Pinot Noir with a classic hint of watermelon rind and mineral notes.

Menetou-Salon

Menetou-Salon is an AOP in the Centre-Val de Loire with vineyards extending over 820 acres and covering 10 communes, including Menetou-Salon itself. Only 3600 bottles of Menetou-Salon Rosé reach American shores each year, so if you can find it, you are in an exclusive club.

Domaine Philippe Gilbert

Menetou-Salon Rosé

Having felt the pull of the soil, Phillipe Gilbert left his occupation as a successful playwright to take over the family estate in the hamlet of Faucards in the midst of Menetou-Salon. The vineyards are scattered throughout the heart of the appellation in prime sectors of the villages of Menetou-Salon, Vignoux, Parassy and Morogues where the soil is a classic mix of clay and limestone sitting on the famous Kimmeridgian basin.

With the assistance of his colleague, Jean-Philippe Louis, Philippe Gilbert has plunged headlong into the system of biodynamic viticulture and the domaine is now certified as an organic producer.

10 Domaine Philippe Gilbert, 2023 Menetou-Salon Rosé ($32)

10 Domaine Philippe Gilbert, 2023 Menetou-Salon Rosé ($32)

100% Pinot Noir, Philippe’s standout rosé is pressed directly and fermented spontaneously—a rare practice for the category since most growers want to ensure market-demanded consistency at all costs. It spends six months in steel, undergoing natural malolactic fermentation. Exuberant and energetic, it offers brambly raspberry, white cherry and grapefruit zest interlaced with notes of pulverized chalk and wet river stones.

Chinon

Playwright François Rabelais (a Chinon local boy made good) wrote, “”I know where Chinon lies, and the painted wine cellar also, having myself drunk there many a glass of cool wine.” That wine was likely red: though capable of producing wines of all hues, Chinon’s focus is predominantly red; last year, white and rosé wines accounted for less than five percent of its total output. Cab Franc is king, and 95% of the vineyards are thus planted. Rabelais’ true stage was set 90 million years ago, when the yellow sedimentary tuffeau, characteristic of the region, was formed. This rock is a combination of sand and fossilized zooplankton; it absorbs water quickly and releases it slowly—an ideal situation for deeply-rooted vines.

Château de la Bonnelière

Chinon Rosé

Respect for tradition and love of family are the twin forces that animate Château de la Bonnelière: In 1976, Pierre Plouzeau bought the old family castle and renovated the property while replanting the largely-vanished vineyards. His son Marc took over in 1999 and has become one of Chinon’s most prolific and talented personalities, responsible for a plethora of marvelous juice—red, white and pink. 43 acres of vines and a 1500-square-meter cellar carved out of the castle’s solid stone foundation provide an environment as beautiful as it is fecund.

11 Château de la Bonnelière ‘M Plouzeau – Rive Gauche’, 2023 Chinon Rosé ($19)

11 Château de la Bonnelière ‘M Plouzeau – Rive Gauche’, 2023 Chinon Rosé ($19)