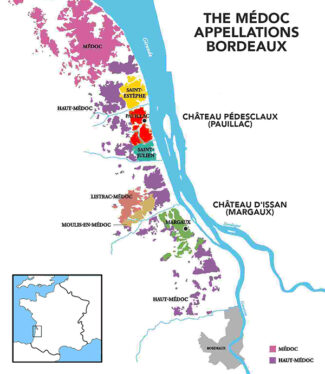

Second Thoughts: Bordeaux Second (And Now Third) Wines Château d’Issan (Margaux 6-Bottle Pack $326) & Château Pédesclaux (Pauillac 6-Bottle Pack $294) + In-Store Tasting ‘Left-Bank Rendez-Vous’ – RSVP

Rather than shedding tears, Bordeaux adds tiers—and classification is what Bordeaux is all about. While the Grand Vin is expected to be the A-game of any château, with technological advancements and an increasingly warm climate, the price of these top-shelf wines has risen with the temperature, and quality is ensured by an ever more rigorous selection of grapes on the sorting table.

Second wines—a tradition begun by Château Margaux in the 17th century—were the logical place to establish grapes deemed unfit for inclusion in the Grand Vin. And since the terroir in which they were grown was often similar, and occasionally identical to the first wines (and generally made by the same vigneron), it stands to reason that the great estates would release these ‘little brother wines’ under some version of their famous name. Château Lafite Rothschild’s second wine, for example, is Carruades de Lafite; Château Margaux’s is Pavillon Rouge du Château Margaux.

This name-game association has a downside, of course: As the prices for a château’s main bottling rose, they found that they could easily command more for second wines as well, and inexorably, these began to be priced beyond the reach of many consumers as well. Especially in the Médoc, the cost of second wines crept up to a price point once paid for the first. Some châteaux found a solution in producing third wines, and although fourth wines are not unheard of, the bulk of a harvest that does end up in one of the three is generally declassified and sold to négociants.

Price Pressure

As mentioned above, any viable business must weigh the needs of customers with their ability to pay for their product, and the cachet associated with First Growths in Bordeaux is so encompassing that maintaining quality outweighs any need for quantity. It’s fair to suggest that for Bordeaux’s most heralded names, second wines are not a bid for publicity, but exist as a vital—and growing—revenue source. In 2010, for example (one of the best years for quality in decades) only 40% of the harvest went into Lafite’s first wine while a full 55% went into Carruades.

In contrast is Château Léoville Barton, who uses about 80% of their grapes for their Grand Vin, a Deuxième Cru. It’s a somewhat unique philosophy, says the late Anthony Barton: “‘We produced some jolly good wines doing things that in the current era would make our oenologist scream. Grapes into one big wooden barrel, crushed by foot in the field. But we made vintages such as 1945 and 1947. The other day I found an invoice for a fiddler who played while we stomped. Now you need velvet gloves for touching the grapes.”

Precise Vinification

Other estates, like Château Pontet-Canet, express a goal of vinifying 100% Grand Vin—a once unreachable star brought closer to earth by advancing technology and better land management. Beyond the biodynamic movement which is sweeping most winemaking regions in the world, Picovale weather stations are increasingly allowing vineyard managers to be proactive in the face of incipient bad weather, especially the dreaded springtime frosts. Experience, formerly the sole means of measuring phenolic ripeness and knowing when to harvest, has guided winemakers in Bordeaux since Roman times, but technology can remove the last traces of guesswork. Brimrose Le Vigneron AOTF-NIR Analyzer calculates and levels of sugar and acidity, bringing groundbreaking insight to the exact time winemakers should be harvesting.

These innovations allow a much more precise product to be bottled, and with the increasing quest for perfection, they are becoming increasingly indispensable, even in a region where tradition is sacred.

Harnessing the Young Vines

Older vines are a legacy among wine growers, and when they reach a certain age, it becomes a point of pride. With an expansive root system and substantial permanent wood, these vines have adapted to their environment and are more resilient to drought and extreme weather. At the same time, they are more prone to disease and damage and produce increasingly smaller yields, and at some point, it no longer makes sense to keep them in commercial production. Maintaining a sustainable economic vineyard means replanting, and in Bordeaux, mature vines are often replaced after about 35 years. After that, it takes between ten and twenty years for a vine’s fruit to reach potential, and a natural outlet for grapes from younger vines is an estate’s second and third wines, where it is expected that the tannins will be a bit coarser and less integrated, but which will mature more quickly than Grand Vin bottlings.

Access to Quality

In fact, the idea that second wines can be enjoyed earlier than their big brothers is one of their main selling points. Great wines may take twenty years to reach their apex; a lesser version may deliver its entire package upon release, or at least, within a few years. Second wines may come from the same winemaker who makes the first, and even the same plots of ground, but the philosophy is different. By using slightly less newsworthy fruit in the second wine rather than the first, the quality of the Grand Vin is expected to remain high; the alternative may to produce more Grand Vin with lesser grapes, but which would consequentially, be available at a lower price. It’s an endless balance, well summarized by Anthony Barton: “While I don’t believe that you can go too far in the search for perfection in wine, you can certainly go too far in search for profits.”

2018 Vintage: Opulent, Sensual and Deeply Colored

Philippe Sereys de Rothschild (owner of Château Mouton Rothschild) compares Vintage 2018 to the legendary ‘59s, which he claims are still near-perfect, with incredible depth and finesse. “It’s always interesting to try to describe a vintage with one word,” he says. “2009 is velvet; 2010 is square. And 2018? The word that comes to mind is ‘dense.’ It’s a vintage that you want to follow.”

According to Bordeaux wine merchant François Thienpont: “In 2018, we saw a very specific weather pattern. The first half was very rainy, and then, after mid-July, it was dry. That means that we didn’t have any vines suffering hydric-stress. They weren’t affected by the drought and the vines were able to do the job for the grapes. It was easy. It was absolutely awesome!”

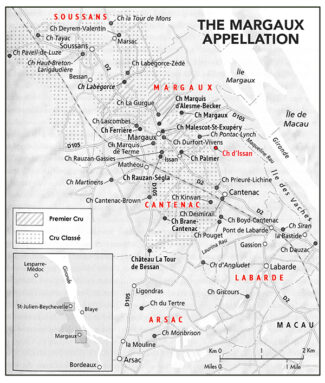

Margaux: Miraculous Marriage Between Density and Grace

In terms of size and renown, Margaux is a vastly important appellation, with 21 Cru Classé properties from the 1855 Bordeaux Classification within its borders. As feminine as the name are the wines of Margaux, at least by traditional standards—they are famous for their perfumed fragrance and lilting, delicate expression of terroir; in cooler vintages, they may come across as lightweights compared to the powerhouses of Pauillac, but in fine vintages like 2018, they are incomparable in grace and depth.

Encompassing nearly four thousand acres of vines, Margaux is the second largest appellation in the Haut-Médoc (after Saint-Estèphe), but the irony remains: The quintessential character of Margaux relies not on size, but on finesse. The velvet and silk that the wine exhibits on the palate combined with the ripe plum and violet aromas that dominate the nose may confuse tasters into thinking that there is a higher percentage of Merlot in the cuvée, but geography gives rise to this softness, built primarily around Cabernet Sauvignon. Margaux is the warmest major appellation in the Left Bank and it is almost always the first to harvest, so floral, red-fruit freshness remains in Margaux, while it may turn into black currant and mulberry notes in other prestigious Left Bank appellations.

Château d’Issan Package: Six bottles; two bottles of each for $326.

CHÂTEAU D’ISSAN

The roots of Château d’Issan’ vines delve deeply into Margaux’s gravel, but not as deeply as the roots of the estate delve into history. One of the oldest producing châteaux in Bordeaux, wines from d’Issan vineyards were used to toast the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine and King Henry the Second. Oddly perhaps, although Cabernet Sauvignon is the dominant varietal today, when d’Issan was classified as a Third Growth in 1855, the wine was produced entirely from a grape that is now all but extinct in Bordeaux: Tarney Coulant.

In 2013, Château d’Issan sold a 50% stake to Jacky Lorenzetti of Château Lilian Ladouys, Château Lafon-Rochet in Saint-Estèphe and Château Pédesclaux in Pauillac. Along with Emmanuel Cruse, the winemaking has been upgraded to include sorting tables and a new pneumatic press along with an increase of the proportion of new French oak barrels used to age the wine; currently an average of 50% of the aging barrels are seeing their first vintage.

First Wine: Château d’Issan, Margaux 2018 ($99)

First Wine: Château d’Issan, Margaux 2018 ($99)

2018 D’Issan is composed of 60% Cabernet Sauvignon and 40% Merlot, half of it aged in new oak and half in second-year barrels for an estimated 18 months. A deep garnet color, it offers blackberry compote, warm cherry pie and cassis with spice box and fragrant earth plus hints of tea behind a core of firm, fine-grained tannins.

Second Wine: Château d’Issan ‘Blason’, Margaux 2018 ($40)

Second Wine: Château d’Issan ‘Blason’, Margaux 2018 ($40)

D’Issan’s second wine, introduced in 1995, is made from the estate’s youngest vines. It is fruity and accessible, offering a bouquet of blackberry and cranberry laced with undergrowth, mint, lavender and tobacco leading to full, fruity mid-palate and a mineral-driven finish.

Third Wine: Château d’Issan ‘Moulin d’Issan’, Bordeaux Supérieur 2018 ($24)

Third Wine: Château d’Issan ‘Moulin d’Issan’, Bordeaux Supérieur 2018 ($24)

Bordeaux Supérieur (mostly red wines) is an appellation tier applied to wines made within the generic Bordeaux AOP zone, and as the name suggests, they are intended to be a ‘superior’ form of standard Bordeaux AOP wines and rely heavily on Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon with smaller amounts of Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot and Malbec.

Moulin d’Issan is silken and sweet; and with 90% Merlot the wine is gentle on the nose and shows tart cherry and raspberry with an underflow suggesting tobacco leaf and integrated chocolate. It’s mouth-filling and briefly luscious, offering the trademark Château d’Issan Margaux framework at a fraction of the cost.

Paulliac: Elegance and Power Coupled with Complexity

Whereas the Right Bank of the Gironde is known for clay-rich soils that produce smooth, softly-fruited wines with balancing tannins, the Left Bank—where vines tend to struggle through limestone and gravel—is known for tannic wines that become exponentially more complex with age. The Left Bank encompasses the Médoc region, whose face, quite arguably, is Pauillac.

Pauillac represents three of the five First Growths named in the 1855 Classification, with another fifteen classified wines adding trophies to the wall, including two heralded Second Growths. The wines of Pauillac contain a characteristic finesse, elegance, and intensity essentially unmatched by any growing region elsewhere in the world. The maritime climate and unique soil matrix, ideally suited to Cabernet Sauvignon, is key to the splendor. Nearly flat, (the average elevation in Pauillac is twenty feet), the subsoil is often composed of alios, a hard sandstone rich in iron, which may account for the appellation’s classic strength and vitality. The châteaux, in the main, are less subdivided than in neighboring regions, making it easier to pinpoint variations in style according to terroir.

Pauillac consists of about 3000 acres of vineyards, which on average produce seven million bottles of wine per year.

Pauillac contains a dozen Fifth Growth estates, each vying to match fame of Château Lynch-Bages, long considered the leader in the category, dubbed ‘the poor pan’s Mouton’ for its rich and powerful style. Among those who consistently outperform their classification, especially in recent years, is Château Pédesclaux, thanks to Jacky, Françoise and Manon Lorenzetti’s commitment to organic viticulture and the addition of state-of-the-art cellar technology. Says wine critic Jeb Dunnuck: “This estate has made leaps and bounds in terms of quality over the past decade, and my money is on the 2018 Château Pédesclaux being the best to date.”

Château Pédesclaux Package: Six bottles; three bottles of each for $294.

CHÂTEAU PÉDESCLAUX

Pédesclaux is classified as a Fifth Growth, and the original accuracy of that designation may be confirmed by the fact that the Pédesclaux family was well-regarded as négociants at the time, and Edmond Pédesclaux was one of the brokers who actually helped determine the 1855 Classification. That said, there has not been a Pédesclaux at the helm since the nineteenth century, but the various owners since have slowly but steadily improved the plots they owned while purchasing additional vineyards. Part of the overall plan has involved rebalancing the vineyards, adding more Cabernet Sauvignon (to which the terroir, Garonne gravel on subsoil of limestone, is particularly suited) and removing rows of Merlot. The current breakdown of the vineyards is 48% Merlot, 47% Cabernet Sauvignon, 3% Petit Verdot, 2% Cabernet Franc.

To the Lorenzetti family, who took over the estate in 2009, land stewardship is paramount; all vineyards are farmed organically and certain plots, biodynamically. Respect for the environment has been at the heart of their approach to viticulture. Once they had restructured the existing vineyards and purchased several high-quality plots atop the Milon plateau (where their rows are interspersed with those of Mouton and Lafite), they introduced exacting and sustainable farming methods to improve the land, and the results are evident in the bottlings, which in recent years far outgun the châteaux’s classification.

First Wine: Château Pédesclaux, Pauillac 2018 ($67)

First Wine: Château Pédesclaux, Pauillac 2018 ($67)

64% Cabernet Sauvignon, 27% Merlot, 5% Cabernet Franc, 4% Petit Verdot, the wine shows a solid core of cassis and blackberry liberally framed by dark cocoa and espresso notes which carries through a spice and licorice finish.

Second Wine: Château Pédesclaux ‘Fleur de Pédesclaux’, Pauillac 2018 ($31)

Second Wine: Château Pédesclaux ‘Fleur de Pédesclaux’, Pauillac 2018 ($31)

59% Cabernet-Sauvignon, 36% Merlot, 3% Petit Verdot, 2% Cabernet Franc from a 120-acre plot, the estates 2018 second wine is characterized by its higher percentage of Merlot, leading to a rich nose of wild blackberries and garrigue, showing wild strawberries and supported by spicy notes of cedar, camphor and pepper. The palate, delicate and fresh, is laced with velvety tannins.

In-Store Tasting (RSVP Required)

Left-Bank Rendez-Vous with Augustin Lacaille

As a special expression of thanks to valued patrons who have supported us over the years, Elie Wine Company is proud to extend an invitation to a special in-store tasting on Monday May 9 from 5:30pm to 7:30pm. With our guest Augustin Lacaille, the charismatic commercial director of the Left Bank châteaux; Château d’Issan, Château Pédesclaux, Château Lafon-Rochet and Château Lilian Ladouys, we will make a vinous trail through the four great Châteaux each of whom offers exceptional quality and remarkable value.

As a special expression of thanks to valued patrons who have supported us over the years, Elie Wine Company is proud to extend an invitation to a special in-store tasting on Monday May 9 from 5:30pm to 7:30pm. With our guest Augustin Lacaille, the charismatic commercial director of the Left Bank châteaux; Château d’Issan, Château Pédesclaux, Château Lafon-Rochet and Château Lilian Ladouys, we will make a vinous trail through the four great Châteaux each of whom offers exceptional quality and remarkable value.

- - -

Posted on 2022.05.07 in Pauillac, Margaux, France, Bordeaux, Saturday Sips Wines, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

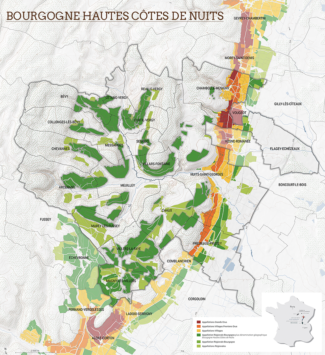

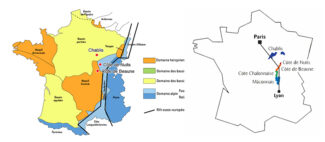

Burgundy Backcountry Riches Prospected in Hautes-Côtes de Nuits and Regional Appellations Overlooking the Slopes of the Great Communes Red, White and Sparkling (9-Bottle Pack $373)

In Burgundy, the vagaries of weather play an integral part in a given terroir’s potential; even the most ideal soil matrix, with a perfect balance of minerals, humus and micro-organisms, is useless if frost kills the buds and rain drowns the roots. The historical divisions among the domains of Burgundy are (compared to Bordeaux) very much on a human scale, with holdings subdivided among families, but nearly all are demarcated, to some extent, based on the immutable quality of the terroir.

What this legal concept did not anticipate is that the weather, volatile from vintage to vintage, might change on a grander scale and bring different weather on a more regular basis. Colder areas, once considered inferior, are currently finding that global warming allows their grapes to ripen more fully, and domains once spared rain are now deluged in the spring.

These changes are also happening on a human scale; the average Burgundian temperature has increased one degree Celsius since 1987, while flowering and harvesting have been on average two weeks earlier in that period compared with the previous two decades.

Among the winners in this high-stakes meteorological gamble are some outlying regions in Burgundy that don’t get a lot of airplay. As a result, these are wines whose prices have not yet caught up with their ever-increasing quality.

Bourgogne Hautes Côtes de Nuits: Typically ‘Nuits’

Due west of Nuits-Saint-Georges, in the wild hinterlands of Burgundy, along southern half of a 12 mile stretch of vineland known as the ‘Champs-Élysées of the Bourgogne’, lies a lesser known wine region ripe for discovery. Once neglected by both growers and patrons, the area known as Hautes-Côtes de Nuits has enjoyed a viticultural renaissance in the past half century that has manifested terroirs similar to those in the heralded Côtes itself.

Overlooking the slopes of Gevrey-Chambertin and extending as far as the wood of Corton, the appellation was officially recognized in 1961 and covers 20 communes; 16 in the Hautes Côtes region in the département of Côte-d’Or, plus the higher areas of 4 communes in the Côte de Nuits where elevations average 1200 feet. Vines are planted along sides of valleys that cut through the Jurassic limestone plateau to the west of the Côte; the underlying rock is the same as that of the Côte but the soil is thin or non-existent, formed by a mixture of eroded limestone and marly subsoil.

2019 Vintage: Concentrated and Vibrant

“At almost every 2019 tasting I was struck by how beautifully the ripe yet precise fruit, the elegant tannins and the lively acidity gelled on the palate. Although all the top red wines from the pinot noir grape have excellent aging potential, most of them are already open and enjoyable. That reminds me of great modern vintages like 1985 and 2009.” – James Suckling.

Bernard Hervet, former director of Faiveley and Bouchard, went even further: “The long hot, dry summer was ideal for Burgundy and created perfect conditions that could perhaps rival 1865, the greatest vintage of all.”

Despite two bouts of frost in April and rain at flowering, conditions quickly righted themselves. Short but intense heat spikes throughout the summer concentrated the juice in small berries (known in Burgundy as ‘marbles’), leaving high tartaric acid levels and low levels of malic, meaning that wines kept a stable acidity even after the second fermentation. As a result, 2019 wines favor concentration and depth while remaining focused, vibrant and with remarkable transparency to individual terroirs.

2018 Vintage: Youthful Appeal

Weather is arbitrary; the decision on when to pick your grapes is not. Nowhere is this determination more vital than in Burgundy (where a harvest can be decimated overnight), and no vintage is more exemplary of this delicate balance of risks and rewards than 2018. For those who waited until full phenolic ripeness, the harvest provided both quality and quantity.

Winter and spring were unusually wet and warm, with rainfall in both January and March twice the average for the time of year. This provided water reserves that was key to vine health throughout the torrid growing season, where temperatures were consistently above average. July brought two ferocious hailstorms, but so successful had been the flowering that there was already a good crop on the vines; in some ways the hail acted as a beneficial green harvest. Since vine age, exposition, soil type, rootstock, pruning method, the number of bunches on the vine and management all influence when fruit reaches full ripeness, the harvest date throughout the Côtes de Nuits varied, with some great growers, including Gevrey-Chambertin opting to pick early to preserve freshness in the wines.

Domaine des Perdrix

Perdrix (translated in English to the partridge that appears on the label) was taken over in 1996 by the Devillards, owners of Domaine du Château de Chamirey in Mercurey, Domaine de la Ferté in Givry, Domaine de la Garenne in Mâconnais and Domaine Rolet in Jura. According the Robert Parker, it is a prime example of the ‘great undiscovered terroirs’ lurking among the more famous domain names of the Côtes de Nuits—it has been at the top of several of his blind tastings. The small, 30-acre estate produces wine from vines whose age averages 35 years; Devillards have invested considerable sum to bring both the philosophy and the technology of Perdrix to its current level.

Domaine des Perdrix, 2018 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits Blanc ($45)

Domaine des Perdrix, 2018 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits Blanc ($45)

100% Chardonnay planted on the high slopes of Prémeaux Prissey at an altitude of 1200 feet, the grapes originate in a single-acre plot of clay and limestone. After harvesting by hand, aging in Allier and Vosges oak (10% new) lasts nine months. The wine is pale gold with green tints, showing crisp apple and lemon on the nose with acacia flowers as an accent. The palate is delicate and slightly unctuous with cream and vanilla on the finish.

Domaine Thibault Liger-Belair

The estate (originally called Comte Liger-Belair) was created in 1720 in Nuits-Saint-Georges, and soon became one of the most important wine growing and trading houses in Burgundy. After many years and successive generations had met with varying degrees of success, Thibault Liger-Belair took over in 2001, and found the 20-acre estate in need of some attention. His immediate switch to organic farming was a matter of necessity as much as responsible stewardship: “The vineyards were in a bad condition, with compacted soils. I couldn’t do anything else other than organics,” he says, and in 2004, he discovered biodynamics: “I saw a change in my vineyard, which went from grey soils to brown/red and then sometimes to black.”

Still, his overarching philosophy is that each vineyard needs something different: “I don’t like 100% of anything: new barrels, whole clusters, etc. My job is to decide which grapes we have and then decide a viticulture and winemaking approach.”

In 2018, he made wine from 23 different appellations and purchased grapes from a ten more, where he had worked the vines himself. “We don’t purchase grapes where we don’t do the work,” he maintains.

Domaine Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Le Clos du Prieuré’, 2018 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits Rouge ($49)

Domaine Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Le Clos du Prieuré’, 2018 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits Rouge ($49)

Putting the ‘haute’ in Hautes, the three-acre plot of Pinot Noir is located at an elevation of nearly 1500 feet. As a result, the climat requires additional hang-time to ripen the grapes, and harvest is generally done a week to ten days later than the rest of the domain’s holdings. Planted with an east-facing orientation on slopes with a 40% grade, the white marl and limestone soils are difficult to work, but reward perseverance. The wine shows ripe aromas of black cherry, raspberry and smoke with a whiff of roasting meat; full and round in the mouth with a persistent, mineral-laden finish. 2,628 bottles produced.

Domaine Thibault Liger-Belair ‘La Corvée de Villy’, 2018 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits Rouge ($49)

Domaine Thibault Liger-Belair ‘La Corvée de Villy’, 2018 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits Rouge ($49)

‘Corvée de Villy’ is a bit more than an acre and a half of stony earth in the upper reaches of Nuits-Saint-Georges on the Chaux plateau. It was planted to Pinot Noir in 1988 and according to Liger-Belair, is comprised of a specific blend of two soils that influence the wine in two steps: “The first 30 centimeters of the soil are composed of red-orange lava clays rich in ferrous elements and then it is the primary limestone that formed the basis for the creation of the Côte. The nose is floral with the aromas of red fruits; the palate is richer and more ‘gourmet’ on first impressions and finishes with freshness and minerality brought by the limestones.” 3,300 bottles made.

Domaine Mongeard-Mugneret

The name ‘Mongeard’ first makes an appearance in Burgundy in 1786, where records show a Mongeard working as vigneron for Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. Skip forward to 1945, when at the age of 16, Jean Mongeard (whose mother was from Famille Mugneret) made wine which he sold by the barrel to négociants. The entire 1945 crop was purchased by Baron le Roy, Marquis D’Angerville, and Henri Gouges, who suggested that the young Mongeard start bottling the wines himself.

In 1975, Jean’s son Vincent began working alongside his father and became responsible for viticulture and vinification of the domain’s wines. He persuaded his father to return to the traditional method of filtering only in certain vintages. Upon his retirement in 1995, Vincent assumed complete leadership of the domain, which now covers more than 75 acres split among 35 appellations.

Domaine Mongeard-Mugneret ‘Les Dames Huguettes’, 2019 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits Rouge ($41)

Domaine Mongeard-Mugneret ‘Les Dames Huguettes’, 2019 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits Rouge ($41)

With an average age of 35 years, the five acres of Pinot Noir vines that produce ‘Les Dames Huguettes’ are planted in deep soils composed of limestone and argovien marls. The grapes are hand-sorted and destemmed at the winery and mature in slightly-used (a single vintage) barrels. The wine is tight and structured, with notes of sappy spring flowers, tart black cherries, forest floor, violets, and damp earth. A fabulous length for this price point; it is certainly a match to most Village-level Burgundies.

Domaine Mongeard-Mugneret, 2019 Bourgogne Rouge ($35)

Domaine Mongeard-Mugneret, 2019 Bourgogne Rouge ($35)

Vines between 28 and 55 years old, planted on decomposed limestone grit over deep clay; 100% hand-sorted Pinot Noir offers a bouquet of rose petals and spicy wild cherry, leading to a silky palate featuring a core of dense black cherry ends with dusty, nicely integrated tannins.

More Backcountry: Burgundy’s ‘Régionales’ Wines

The whole of Burgundy produces around 200 million bottles of wine per year, and more than half of it falls under the appellation ‘Régionale’. This broad, encompassing catchment covers 23 individual AOPs producing wines on a vast array of terroirs, with chalky soils around Joigny in the north and granitic soils in the south (although limestone-rich, marly soils lie beneath the majority of the appellation).

These wines are considered entry-level, but with the advent of a warming climate and passionate input from a younger generation of winemaker, the wines are of increasing quality.

Domaine Henri Gouges

Considered by many to be Nuits-Saint-Georges’ top domain, the estate has been passed down through many generations and is, to this day, a family affair, with four Gouges at the helm.

Grégory Gouges has been the domain’s winemaker since 2003; Pierre today runs the business end with his cousin Christian, son Grégory, and Grégory’s cousin Antoine. The vineyards cover 36 acres, including seven of the best well-positioned Premiers Crus: Les Chaignots, Les Chênes Carteaux, Les Pruliers, the monopole vineyard of Clos des Porrets-Saint-Georges and nearly three acres each of each of the appellation’s most famous vineyards, Les Vaucrains and Les Saint Georges.

Domaine Henri Gouges, 2019 Bourgogne Rouge ($53)

Domaine Henri Gouges, 2019 Bourgogne Rouge ($53)

From the bottom of hillside in the lieu-dit ‘Des Petits Chaliots’, the wine displays pronounced intensity, with a nose showcasing strawberry, red rose, cured meat, gravel, underbrush and white pepper, finishing with crushed-rock minerality.

Domaine Castagnier

With properties found in the heart of the Côte de Nuits, Jérôme and Jocelyne Castagnier—working a scant ten acres—manage to produce four Grands Crus in the prestigious soils of Gevrey-Chambertin, Morey-Saint-Denis, Chambolle-Musigny and Vougeot.

Says Jérôme: “I’m the fifth or sixth largest owner of Grand Cru in Morey-Saint-Denis, but when it comes to Village-level appellation Morey-Saint-Denis, I’m the smallest. All I have is two rows of vines. That’s one barrel of wine.”

Having left a career as a trumpet player to pursue the vine, he adds, “After my studies at the Conservatory in Dijon and the Conservatory in Paris I took a job in the French Republican Guard Band, working at the Élysée Palace under both Jacques Chirac and Nicolas Sarkozy. In 2004, at the age of 26, I had to decide whether to continue the career in music or to uphold the family tradition. I chose the latter and returned to Morey-Saint-Denis, thus becoming the fifth generation in my family running the domain.”

Among the younger crop of vignerons who manifest a worldview based in respect for the environment, the Castagniers rely on biodynamics and earth-first techniques at every phase of the winemaking process.

Domaine Castagnier, 2018 Côteaux Bourguignons Rouge ($49)

Domaine Castagnier, 2018 Côteaux Bourguignons Rouge ($49)

Bourgogne Grand Ordinaire or Bourgogne Ordinaire was reimagined in 2011 as Côteaux Bourguignons; it is a generic appellation that extends the length and breadth of Burgundy. Although they are intended as everyday wines, the Castagniers have produced an exceptionally elegant Pinot with complex aromas of plums, raspberries and cherries and fresh red fruit flavors in the mouth with earthy floral, mushroom and mineral notes and balance acidity.

Domaine Manuel Olivier

Like Jérôme Castagnier, Manuel Olivier—despite a childhood spent among the vines—did not follow in the family footsteps directly out of the gate. First, he traveled to Switzerland to pursue his passion for skiing, and along the way, decided that he was equally passionate about wine. He entered the field (literally) with a few acres of vines in 1990, which has grown to nearly 30 in Hautes-Côtes de Nuits, the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune.

Using wild yeast, his goal is to produce approachable, subtle wines where the fruit expressed delicacy. He says, “This can only be obtained by an obsessive attention to detail; handpicking, low temperature maceration and use of natural yeast. I destem half of my harvest and take a minimum of seven days low-temperature maceration prior to fermentation.”

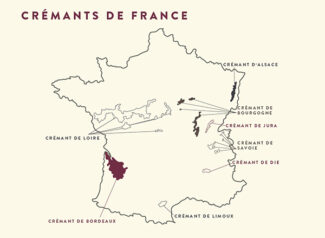

Domaine Manuel Olivier Crémant de Bourgogne Brut ($26)

Domaine Manuel Olivier Crémant de Bourgogne Brut ($26)

Sparkling Burgundy made its entrance into history in 1830 when it was lauded by the poet Alfred de Musset (1820-1857) in his “Secrètes Pensées de Raphaël” — ‘Raphaël’s Secret thoughts.’

Unlike Champagne, the appellation is exclusively applied to white base wines or rosé, which must be made from Pinot Noir, Chardonnay (minimum 30%), Gamay (20% maximum), Aligoté, Melon and Sacy (a low-acid varietal grown within the Yonne and Allier départments).

Domaine Manuel Olivier Crémant de Bourgogne Brut is 25% Aligoté, 50% Chardonnay and 25% Pinot Noir. A méthode traditionelle, it bursts with clean, crisp flavors of apples and white fruit; juicy and full-bodied, with fine floral details and citrus spice keeping it buoyant into a long finish.

Domaine Manuel Olivier Crémant de Bourgogne Rosé Brut ($26)

Domaine Manuel Olivier Crémant de Bourgogne Rosé Brut ($26)

100% Pinot Noir made from various parcels throughout the Hautes-Côtes de Nuits. Soft raspberry and fresh apricot aromas with a hint of sesame seed highlight a lovely mousse; palate flavors include white cherry, nectarine, and tart strawberry. Medium acidity, light body with a creamy finish.

- - -

Posted on 2022.05.01 in Hautes-Côtes de Nuits, Côteaux Bourguignons, France, Burgundy, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

A Letter to The Editor: re: “The Producers of Right Now.” Four in Eight Wines. (8-Bottle Pack $228)

When our friend and colleague Leslie Pariseau from ‘PUNCH’ Drinks sent out an email to wine retailers and restaurant/bar managers asking about the state of the art in wine appreciation today, we thought it was worthy of a detailed response. In brief, she asked four pertinent questions:

• Which producers do you feel represent the best of wine culture right now?

• What can each of these producers teach us about zeitgeist values right now (and by right now, we mean right now)?

• What do you feel they say about the evolution of your own tastes?

• What do you think goes into the attraction toward these producers, both among wine people and consumers in your market (e.g. label design, story, labor practices, agriculture, etc.)?

These are the very questions we ponder with every bottle we shelve and every package we assemble for our weekly wine offerings. They represent our ongoing fascination with winemaking trends vs. winemaking traditions, and they spearhead our search for labels (many obscure) that represent a growing movement in every wine region we cover—a move toward minimal interventionalism.

In all things wine, ‘balance’ is the key to the kingdom; it is a term interchangeable with harmony and may reference acid, alcohol level, grape sugars and tannin, but also, a scale in which the long-term health of the product is considered along with the flavors inherent on release. More than just a radar blip or a grab for social capital, a naturalistic focus in winemaking is not only more honest approach to the art of fermentation, but it is better for a sustainable environment: It’s a nod to the past and a gesture toward the future.

These are four of our wines whose owners and winemakers check all the boxes. Each of these selections expresses the evolution of style through innovation while honoring heritage through tradition. Not only that, but each puts an emphasis on Ms. Pariseau sense of immediacy: They are wines that will not require years to mature but are quite ready to drink… right now.

Château de Fosse-Sèche

(Saumur)

Like an iron-red ruby amid the seafoam of limestone, the soils of Fosse-Sèche are rather unique to the Loire—a fact that has been recognized since the 13th century, when Benedictine monks first planted vines there. Move the clocks ahead to 1998, when the Keller-Pire family took over the estate, enraptured by the beauty of the surroundings and its exceptional terroir, composed of iron oxide and flint silex just beneath the topsoil. Twin brothers Guillaume and Adrien Pire, who grew up in Madagascar, brought with them not only degrees in agronomy and viticulture, but a deep respect for the wild land of their youth. Along with their wives Julie and Cécile, they have instilled Fosse-Sèche’s 800-year history with an abiding belief in a holistic remake of all phases of winemaking.

Adrien Pire-Keller

If a single word was to describe the most profound change that has taken modern European winemaking by storm, it is biodynamics—techniques that their forebears may have practiced by necessity without naming it, but which today is a nod to the cosmic continuum of which agriculture is only a part. Two-thirds of the Fosse-Sèche property is a natural reserve, with a bird sanctuary, acres of honey flowers, goats, bees and thriving wetlands; the hundred acres of vine are in a single parcel and are planted to Cabernet Franc (70%) and Chenin Blanc (30%).

Château de Fosse-Sèche ‘Arcane’, VdF* Loire Blanc 2019 (Natural) ($39)

Château de Fosse-Sèche ‘Arcane’, VdF* Loire Blanc 2019 (Natural) ($39)

A cuvée from the estate’s finest hand-sorted Chenin Blanc, aged on the lees for nine months in French oak, producing a richly-complex and honeyed wine juicy with quince, lime peel, apple and fresh almond, finishing with chalky crispness.

Château de Fosse-Sèche ‘Eolithe’, VdF* Loire Rouge 2018 (Natural) ($34)

Château de Fosse-Sèche ‘Eolithe’, VdF* Loire Rouge 2018 (Natural) ($34)

‘Eolithe’ is the geological name for the iron-sprinkled flint that forms the winery’s unique soil structure. Relatively low in alcohol for a fully ripened Cabernet Franc (12.5%), the wine is rich with purple flowers (violets) and purple fruits, plums and blackberries; a piercing spine of acidity keeps the flavors lively and promises potential for tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow—if you don’t drink it tonight.

*VdF: Established a decade ago, Vin de France is a special designation meant to allow vintners to blend wines from different regions and new combinations of grape varieties, and represented a fundamental shift for a country tied to geographic classification for its wines. It has been a resounding success, with more than 340 million bottles sold annually under the VdF label, much of it increasingly high-quality and medal-worthy.

Domaine de la Charmoise, Henry Marionnet

(Touraine)

If the prevailing spirit among modern winemakers acknowledges a spiritual connection between humans and earth, it is no wonder that Henry Marionnet is known as ‘The Pope of Gamay.’ The vines of Domaine de la Charmoise—150 acres mostly dedicated to Sauvignon Blanc and Gamay—grow at the highest point between the Loire and Cher rivers, where a combination of aspect and geology provides plenty of sunshine and shelter against spring frost. In that environment, which his family has owned since 1850, Henry Marionnet says: “Give me the most beautiful grapes in the world and I will make you the greatest wine in the world.”

As would suit a purist’s purist, his mentor was the earth itself: “I never attended viticultural school; my winemaking education involved working with the horses ploughing and clearing, and with a pickaxe, working the ground between the vines by hand. When I took over Domaine de la Charmoise in 1967, I began to change things. Some of the vines I inherited were of questionable merit, hybrids or similar sub-standard stock, so I set about replanting and expanding the vineyards.”

Father and Son: Henry and Jean-Sébastien Marionnet

Having recently succeeded his father in managing the estate, Henry’s son Jean-Sébastien has brought his own perspective to Domaine de la Charmoise, expanding the range to include Côt (Malbec) and Chenin Blanc as well as some Loire’s rarest varietals. To be sure, Henry’s presence is still widely felt—as an advisor and a lodestar.

Henry Marionnet ‘Renaissance’, Touraine 2018 (Natural) ($36)

Henry Marionnet ‘Renaissance’, Touraine 2018 (Natural) ($36)

“Here we only make special wines,” says Henry Marionnet. “Wines that others don’t make.”

The swagger touted by ‘Renaissance’ centers on a plot of ungrafted Gamay planted in 1992; Marionnet claims that it is the only such vineyard in Europe. The soil is stony, flinty clay combined with silica which warm up quickly and is known locally as ‘perruches’—a word that translates directly as ‘parakeets.’ Carbonic maceration may occasionally turn Gamay into bubblegum, but here, from the Loire’s legendary 2018 vintage (vinified on natural yeast and bottled without sulfites) it is bright and beautiful, suave and supple, exhibiting a refined nose and a juicy palate with notes of violet, peony and fresh red-fruit syrup.

Domaine de la Charmoise ‘Première Vendange’, Touraine 2019 (Natural) ($23)

Domaine de la Charmoise ‘Première Vendange’, Touraine 2019 (Natural) ($23)

The Gamay that produces ‘Première Vendange’ is (as both Marionnet and the barons of Beaujolais would like to make clear) traditional Gamay Noir à Jus Blanc as opposed to the red-fleshed varieties often used to add color to other wines. The vines that make up the cuvée were planted in 1967 and 1978 on a combination of flinty stones in a mix of sand, gravel and clay. The fruit is picked by hand and whole-bunch fermented in stainless steel vats via carbonic maceration, a process continued by indigenous yeasts. The result is velvet smooth with lithe, ripe fruit beneath a floral canopy that shows hibiscus and violet and a touch of anise.

Bodegas y Viñedos Artuke

(Rioja)

The French have long celebrated micro-terroirs, recognizing in their system of ‘lieu-dit’ and ‘climat’ that certain parcels of land produce wines identifiably unique from those nearby, even if they share an appellation. Vines are influenced by soil, aspect, rainfall, air drainage, and even the subtlest differences can make a tangible difference in the resulting wine.

Arturo de Miguel

Brothers Arturo and Kike de Miguel have re-imagined the concept in Rioja Alavesa. Artuke (a portmanteau of their two names) consists of 32 different vineyard plots on 54 acres that fall within a geographic triangle formed by the villages of Baños de Ebros, Abalos and San Vicente—all north of the Ebro River and each with unique terroir. Traditionally, Spain’s Gran Reservas have been sourced from a multitude of vineyards, and the art was seen in the expertise of the blend and the changes wrought by long aging prior to release. The brothers have chosen to reject the constraints of Rioja’s classification system (which is based primarily on time and type of aging) to focus instead on vinifying small cuvées of indigenous varieties, and aging them for a shorter time in neutral barrels in order to capture the purest, most vivid expressions possible.

Artuke ‘Finca de Los Locos’, Rioja 2018 ($35)

Artuke ‘Finca de Los Locos’, Rioja 2018 ($35)

Finca de Los Locos is a terraced site that overlooks the Ebro River and Paso Las Mañas. At more than 2000 feet elevation, the wind-swept, pebble-strewn slope is the highest in Samaniego. 80% Tempranillo and 20% Graciano from vines planted in 1981; the name comes from the assignation neighbors gave Arturo and Kike’s grandfather when he first planted vines in the shallow chalky soil: ‘Loco’—crazy. Loco boy makes good with this sapid, solidly Mediterranean-flavors of fresh herb, dry earth, dusty tannins and crisp, almost salty minerality. 10,800 bottles made.

Artuke ‘Artuke’, Rioja 2021 ($17)

Artuke ‘Artuke’, Rioja 2021 ($17)

Far from the grapey Kool-Ade that often sums up Beaujolais Nouveau, this carbonic offering is 95% Tempranillo and 5% Viura (a white grape a.k.a. Macabeo; one of the Cava trinity). It is beautiful, fragrant and luscious with a nose of violets and thyme, a rich mid-palate of black cherry and cranberry underscored by orange peel and Damson plum.

Uva de Vida

(Castilla – La Mancha)

“If we take care of the earth, we take care of ourselves,” promises Carmen López Delgado. “Life has given me a new opportunity.”

She is alluding to the sudden illness and prolonged recovery that refocused her cosmic viewpoint and convinced her that her personal renewal could be mirrored in the ways she tended a vineyard. “We made this decision when my illness pushed us to look for everything related to living and life in seeking to recover health.”

Carmen López Delgado

In 2005, with her partner Luis Ruiz, she pioneered biodynamic agriculture and winemaking throughout a 20-acre vineyard in Santa Olalla near Toledo. The dry continental climate of central Spain was ideal for the cultivation of Graciano, of which she planted twelve acres compared to five of Tempranillo. That alone makes her iconic; Graciano is rare enough in Spain, let alone among the cereal fields and Cornicabra olive groves of Castilla-La Mancha.

Uva de Vida ‘Latitud 40’, La Tierra de Castilla 2018 (Natural) ($24)

Uva de Vida ‘Latitud 40’, La Tierra de Castilla 2018 (Natural) ($24)

Uva de Vida winery sits at the wine-friendly 40˚ northern latitude, which circumvents the globe to include northern California, Sardinia and about half of the wine producing areas in China. Here, forty miles south of Madrid, it suits Graciano—the sole varietal used here. Although the ‘Vino de la Tierra de Castilla’ designation carries with it slightly less stringent regulations that of the prestigious DO of Castilla-La Mancha, like the ‘Super Tuscans’, gems may be found among the iconoclasts. Ideally served slightly chilled, ‘Latitud 40’ displays freshness on the nose with hints of lilac, menthol and pie cherries. On the palate, wild blueberries take center stage and the menthol shows a mint-leaf edge. The finish is long and juicy with a slight hint of chocolate. 20,000 bottles made.

Uva de Vida ‘Biográfico’, La Tierra de Castilla 2020 (Natural) ($20)

Uva de Vida ‘Biográfico’, La Tierra de Castilla 2020 (Natural) ($20)

The 2018 version of this vibrant wine contains a 50/50 blend of Tempranillo and Graciano grown in clay-limestone soils at an altitude of about 1600 feet. Hand-harvested and fermented on ambient yeasts, the wine is clarified naturally and bottled unfiltered without Sulphur. The dark color belies a lyrical, almost floral quality to the wine; lilac and violet notes appear on the nose, with bright, spicy red fruit supplied by the Graciano tempered with the earthy tannins of Tempranillo. 8,800 bottles produced.

- - -

Posted on 2022.04.28 in Saumur-Champigny, Touraine, La Tierra de Castilla, France, Spain DO, Wine-Aid Packages, Rioja DOC | Read more...

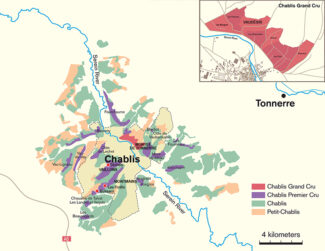

Pure Chablis: The Distinct Identity of Grand & Premier Cru Climats of Burgundy’s Other White Wine by the Talented Guillaume Michel in 2019 (9-Bottle Pack $399)

Most growers in Chablis produce wines in two of the region’s four sub-appellations and many do it in three, but very few make wines in all four. Louis Michel & Fils is one of the few and this package is a pinnacle cross-section of the styles produced by a respected house in a venerated vintage like 2019.

For much of its history, Chablis has stood on a climactic knife’s edge, gambling on whether or not the Chardonnay crop would ripen in Burgundy’s northernmost wine district. Oil-burning smudge pots were once a familiar sight in the spring to prevent frost from harming young buds. But so profoundly has the changing global climate affected the region that there are now those who wonder if conditions will ultimately warm to a point where Chablis loses the cool-weather qualities that make it so distinctive. If so, we may be experiencing the Golden Age of this ethereal golden wine, and 2019 is a case in point.

What Lies Beneath

Chablis with shellfish is a classic culinary matchup, so it’s beautiful irony that Chablis owes its very existence to this variety of marine life: In 1904, agronomist Georges Chappaz noted an abundance of tiny comma-shaped fossils (Exogyra virgule) in the subsoils of Chablis, forming banks of limestone. These fossilized shellfish, first observed in Kimmeridge, England, originated in the Late Jurassic era around 145 million years ago and Chappaz classified it as Kimmeridgean soil. It is so prevalent throughout Chablis that it can often be seen breaking the surface, as it does along the shoreline of Dorset in the famous white cliffs.

“The vineyards of Chablis have a sole religion: The Kimmeridgean,” writes Jacques Fanet in ‘Les Terroirs du Vin.’ In fact, the sedimentary basin in which the region sits is unique in Burgundy; once submerged by an ocean, Kimmeridge clay is intermixed with rich grey mudstone, forming the basis of Chablis’ terroir and accounting for the wine’s renowned purity, expressed in an array of sophisticated undertones—especially in Chablis’ unique minerality.

Kimmeridgean subsoils of gray marl alternating with bands of limestone rich in fossils of Exogyra virgula, a small, comma-shaped oyster.

Kimmeridgean subsoils of gray marl alternating with bands of limestone rich in fossils of Exogyra virgula, a small, comma-shaped oyster.

Acid Trip: Chardonnay in Chablis

Chardonnay finds Valhalla in Chablis, and it owns exclusive rights to the AOP—no other varietal is permitted in the four sub-appellations, Grand Cru, Premier Cru, Chablis (the classification most widely available) and Petit Chablis. Even the entry level-wines display the region’s characteristic northern-clime steeliness and wet-stone backbone although these simple wines are not equipped for aging and are best enjoyed shortly after release.

The height of terroir expression that Chardonnay achieves in Chablis is unmatched in France, and arguably, anywhere else in the world. A result of a cool climate (closer to Champagne’s than the warmer Côte d’Or to the south) combined with technique—steel-tank fermentation and a frequent disdain for malolactic fermentation allows the wines to be fruity, acidic and textured. The more hallowed crus, with vineyards at higher elevations or closer to the Serein River, may use oak for aging, but even then, richness is not necessarily the goal that it is among the Côte de Beaune’s blockbusters; in Chablis, winemakers seek to temper some of the sharpness that may define Chablis from the lesser categories.

Louis Michel & Fils

“CHABLIS DES AMATEURS”

Folks who say ‘yes’ to the magic of Chablis will appreciate the things to which winemakers Jean-Loup Michel and his partner/nephew Guillaume Gicqueau-Michel say ‘no’: Oak, bâtonnage and added yeast. Since 1970, fermentation has taken place entirely in stainless steel to preserve the essence of the Chardonnay grape—Michel & Fils is perhaps the best-known proponent of entirely oak-free wines, even in his three Grand Cru offerings. Bâtonnage—the stirring of the lees to make the wine fatter and richer—is atypical in Chablis, and at Michel & Fils, unheard of.

The Michel family has been a presence in Chablis since 1850. Situated in the heart of the village, the estate covers 60 acres that spread across over the very first slopes that were discovered by Cistercian monks in the 11th century and include three Grand Crus (Grenouilles, Les Clos, and Vaudésir), seven Premier Crus (Montmain, Forêts, Butteaux, Butteaux “Vieilles Vignes”, Vaillons, Séchets, Fourchaume and Montée de Tonnèrre).

The domain also produces village-level Chablis from twenty named communes and a Petit Chablis; offering wines from all four sub-appellations make Louis Michel a rarity among local producers.

2019 Vintage: Concentration and Complexity on All Tiers

Louis Moreau, president of the Chablis Commission of the Burgundy wine board, is 2019’s most vocal champion, announcing, “We have produced a top-quality vintage.”

Budburst was about two weeks earlier than in the copious 2018 vintage, and a cold spell through April that reduced the final yield, which was down about 40% over the previous year. The stressed vines bore only a single bunch of grapes per bud rather than the usual two or three.

It was an unusually dry summer with heat spikes in late June, late July and early August. Older vines suffered less because of their established root systems while parcels on shallow and stony soils were more severely impacted. The temperatures fell a little in August, but conditions remained dry and harvest began on the 11th of September and lasted ten days, impressively quick for Chablis.

The Grands Crus: Keeping Potential

The ne plus ultra in the region, Chablis Grand Cru, represents only about 1% of total Chablis production; it is comprised of seven climats within the commune of Chablis itself and in the hamlets of Fyé and Poinchy on the right bank of the Serein River, which runs to the northeast of the village of Chablis. The names of the vineyards (Blanchot, Bougros, Les Clos, Grenouilles, Preuses, Valmur and Vaudésir) feature prominently on labels due to the distinct characteristics of each, and are found at elevations between 325 and 825 feet for a total of about 250 acres.

The signature of a Grand Cru Chablis is the perfect balance of fruit-based fattiness and bracing acidity; it is a refreshingly dry wine with nuances based on the individual vineyard, but the common notes to expect include the elusive scent of freshly-sliced mushrooms and a discreet touch of honey. Most impressive in a wine with limited exposure to the preservative qualities of oak is its ability to age and improve, ten years minimum with fifteen years or more well in the realm of possibility. With maturity, the earthiness and nutty-qualities of Grand Cru Chablis increase as forward citrus fruit fades and an intriguing spiciness takes over.

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Grand Cru Vaudésir ($90)

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Grand Cru Vaudésir ($90)

Vaudésir sits in an east-west valley within the Grand Cru hill overlooking the town of Chablis. The vineyard covers 40 acres of steep land above the Grenouilles Grand Cru site on the hill just east of Preuses; it is shaped like an amphitheater and is cut through by a track known as the Chemin des Vaudésir, giving it a double orientation, with half of its vines facing south and the remainder facing southwest. This topography helps to distinguish Vaudésir from other vineyard site, as the steep slopes provide some protection from northerly winds and vines instead benefit from good exposure to sunlight. The wine reveals notes of rhubarb and acacia flower with buttery, brioche aromas and a faint hint of coconut.

*click on bottle for more info

The Premiers Crus: Structured with Good Length

Longevity is not only a hallmark of this appellation’s palate sensation: more than half of the climats entitled to wear the ‘Premier Cru’ label had their present-day names by 1429. Chablis Premier Cru represents about 14% of Chablis production, with sites scattered on either side of the Serein River and covering around 2000 acres. As in Bordeaux, where the location of the vineyard compared to the Dordogne and the Garonne determines the style and quality of the wine, the case is similar in Chablis, where left bank wines tend to be more floral and fruit-centered whereas right bank wines are steely and mineral-focused.

Further illuminating the subject is Marc-Emmanuel Cyrot of Domaine Millet, who observes, “The right bank provides complex, well-balanced wines, with a maximum of minerality and vivacity. Those on the left bank are very aromatic, with a less full-bodied character.”

Again, as in Bordeaux, this is the result of soil, topography and exposure to the sun: On the right bank, close to the village, many of the well-known Premiers Crus share similar geology, exposition and characteristics with the Grand Crus. To the left of the river, a different style emerges, with many steep-sided vineyards oriented southwest-northeast, east-facing slopes and varying ratios of limestone and clay.

Of the 40 vineyards that fall under the Premier Cru category, 17 are reckoned to be superior, or ‘flag-bearing’ climats. Among these 17, vineyard differences are pronounced and subtle, but with age, the individualism of the respective climats becomes even more apparent.

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Premier Cru Montée de Tonnerre ($45)

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Premier Cru Montée de Tonnerre ($45)

Set slightly back from the Grands Crus vineyards, Montée de Tonnèrre abuts Blanchot, where its moderate slopes, exposed to the west, welcome the sun in the afternoon. The grapes are protected from the East winds and ripen without much effort while the shallow soil, underlain with Kimmeridgean marly limestone, reveals veins of blue clay to gives the wines both minerality and energy. Montée de Tonnèrre is also an umbrella climat that covers approximately one hundred acres and includes Chapelot, Côte de Bréchain and Pied d’Aloup.

*click on bottle for more info

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Premier Cru Montmain ($38)

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Premier Cru Montmain ($38)

Montmain is both an individual Premier Cru climat sitting to the southwest of Chablis town; it is also an umbrella title that encompasses the Premier Cru vineyards of Forêts and Butteaux. The entirety of Montmains occupies just under three hundred acres of southeast-facing slope in a valley that runs parallel to Vaillons, just over the hill to the north.

From Michel’s four parcels come a lively wine that exudes ripe apple, spicy floral aromas, toasted almonds, anise and a chalky combination of candied lemon peel and damp stones.

*click on bottle for more info

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Premier Cru Butteaux ($41)

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Premier Cru Butteaux ($41)

From four parcels spread over the steep Butteaux slopes; Michel’s total holdings in Butteaux are a little over seven acres. The wine is immediately elegant with an emerald character; soft, leafy herbs, a flint and Granny Smith apples preceding a thrilling rush of chalky acidity and pithy lemon-lime.

*click on bottle for more info

The Old Vines Enigma

The age of a fruit-producing vine has an almost mystical effect on vignerons, who proudly announce the pedigree of a given parcel, often on the label, when it has reached a certain point, frequently between 50 and 100 years old. As the prevailing wisdom insists, an unusually high proportion of the world’s most beautiful wines are the product of vines in this age group.

Not all winemakers and enologists agree on a guarantee of quality among old vine wines, but what is certain is that they tend to be expensive to work with since everything must be done by hand. Not only that, but old vines (often referred to as ‘Vieilles Vignes’ on the label) are far less productive; a 100-year-old vineyard might yield 2 tons per acre whereas a 10-year-old climat would be more in the range of 20.

In either case, old vines are a fascinating talking-point; a beacon for talent, connection, symbolism and heritage.

Louis Michel & Fils, ‘Vieilles Vignes’ Chablis Premier Cru Butteaux ($47)

Louis Michel & Fils, ‘Vieilles Vignes’ Chablis Premier Cru Butteaux ($47)

The southernmost of the three Premier Cru climats that make up the wider Chablis Montmain Premier Cru title, the stopes here are steep and the soils rich in chalky limestone. Louis Michel’s two-acre plot is well over sixty years old, with vines planted in 1955. Yields have so diminished that the old vine harvest is vinified and aged separate from the others, as one might treat a Grand Cru. The wine shows notes of condensed milk, acacia flowers and licorice leading to a warm finish with peach jelly and baked apples.

*click on bottle for more info

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Premier Cru Forêts ($41)

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Premier Cru Forêts ($41)

Forêts is a south-facing slope a few miles south of the commune of Chablis; it is delimited from neighboring Butteaux by its terroir. While the two sub-climats share the same Kimmeridgean subsoils, with high proportions of limestone, there is some variation in texture. Forêts soils tend to be stonier and shallower than those in Butteaux with more clay, giving slightly more concentrated mineral characters to the wines.

In Michel’s two parcels, the bedrock is close to the surface—the depth can be measured in centimeters. The resulting minerality in the wine is pronounced; a pure nose of white flowers lemon and oyster shell leads to a rich and supple mid-palate and an expressive finish.

*click on bottle for more info

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Premier Cru Séchets ($41)

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis Premier Cru Séchets ($41)

Located on the upper southeast-facing slopes on the western side of the Serein River, Séchets has a generally cool terroir that is widely considered one of the best in Chablis, producing taut, razor-sharp wines. The vineyard has a more easterly aspect than many of the more southerly oriented vineyards in Vaillons, so the vines are exposed to gentle morning sun that is less intense than that felt on the steeper slopes to the west. The cooler microclimate allows a long, slow ripening period that allows the grapes to retain their characteristic acidity while still developing aromatic complexity. Once vinified with Vaillons, Michel & Fils has made a separate Séchets since 2010. It delivers a fine blend of apple, pear, fruit blossoms, chalky soil tones and a nice top-note of beeswax.

*click on bottle for more info

The Village: Mineral and Green Apples

Accounting for 66% of Chablis production, the straightforward village-level appellation is the largest by far; it spans a thousand acres and represents a very pure expression of Chardonnay itself, unadorned by wood; if any oak is used, the barrels are larger and older and do not impart much influence. Instantly recognizable aromas are green apple, chalky minerality and one of the true hallmarks of Chablis, aromas of freshly-turned, dry hay.

Styles may vary from village to village and among younger, innovative winemakers as opposed to those who are more steeped in tradition, but the classic Chablis Village is marked by racy acidity and stony, steely undertones.

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis ($31)

Louis Michel & Fils, Chablis ($31)

A cuvée which blends grapes from eight different areas, nearly all from the left bank of the Serein, Lieu-dit Pargues in the Forêts valley, Vaillons and a unique parcel located just below the Montée de Tonnèrre. Vines were planted between 1960 and 1988 and the wine was matured 10 months in stainless steel tanks with the least possible handling. Round, pure, and bursting with ripe apple, toasted brioche, yellow plum with a touch of salinity; the wine is persistent, acidic and finishes with chalky minerality.

*click on bottle for more info

The Petit Chablis: Floral and Citrus Accents

Just as Grand (French for ‘big’) Cru represents the smallest of the four Chablis appellations, Petit (French for ‘small’) Chablis is nearly five times the size of the Chablis AOP, overlapping most of it and extending beyond it. These wines generally originate in lower-quality terroirs and the wines they produce are predictably lesser in quality. Petit Chablis is usually the first to harvest, and from grapes with less hang time comes wine that is simple, refreshing, acidic and bright on the palate. They show floral notes of hawthorn and acacia mingled with lemon-lime and grapefruit over a mineral base that is said to resemble the odor of a flintlock gun.

Louis Michel & Fils, Petit Chablis ($32)

Louis Michel & Fils, Petit Chablis ($32)

From right bank slopes where the soils are shallow and stony, though rich in organic matter. Rather than the Kimmeridgean soils that underlie Grand and Premier Cru climats, the limestone here is Portlandian, which is younger and fossil-free, producing wines with more citrus and less chalk. This wine comes from vines planted between 1991 and 1999 and has undergone spontaneous malolactic fermentation, leading to a pale-yellow wine with greenish glints; it is lively with acid and shows apple peel, white flowers, grapefruit and peach.

*click on bottle for more info

- - -

Posted on 2022.04.16 in France, Burgundy, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

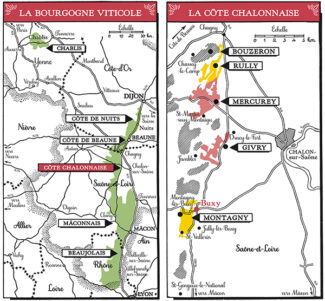

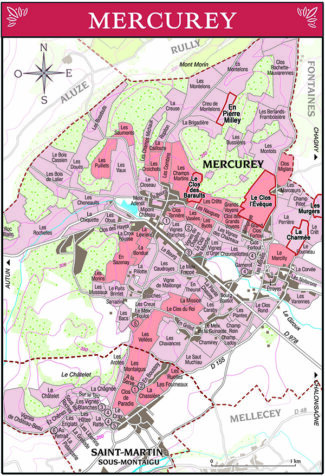

Exploring Mercurey: Vintage 2019 Red Burgundy Bounty From a Mosaic of Soils and Terroirs. (8-Bottle Pack $341)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gouffier

Frédéric Gueugneau may be seen as an archetype in the new blood that has infused Mercurey over the past decade. As a young man in the village of Fontaines (which sits between Mercurey and Rully) he was a laborer in the vineyards of Gouffier, which consisted of thirteen acres spread across eight appellations. Then under the direction of Jérôme Gouffier, the estate had been in the same family for two centuries.

In 2011, upon the death of Gouffier, Gueugneau was asked by his neighbors to take over the day-to-day management of the estate, bringing with him the eight years of experience he’d gained at La Chabliesienne, a wine cooperative in Chablis. He began by reinvigorating the farming philosophy, introducing organic practices; along with his partner Benoît Pagot, Gueugneau brought fresh thinking to the vines and to Gouffier itself—a picturesque estate that finds focus in a stunning, stone-domed cellar that once served as a bunker in the time of Napoleon.

Another unique feature of Gouffier is its close alliance with a single cooper. Doreau Tonneliers of Cognac is instrumental in finding the perfect match between barrel and wine, and in fact, nearly 20% of the wood used to make the barrels used by Gueugneau and Pagot comes from the forest just beyond the property’s walls.

Gouffier, Mercurey Premier Cru Clos l’Évêque 2019 ($48)

Gouffier, Mercurey Premier Cru Clos l’Évêque 2019 ($48)

One of 32 Premier Cru vineyards in Mercurey, Évêque translates to ‘Bishop’, signifying that the vines once belonged to the Bishopric of Chalon-sur-Saône—a time when it was considered the best vineyard in Mercurey. It is situated on a geological fault-line in the Val d’Or where the subsoils are deep and silty with small pebbles to provide adequate drainage to the vine roots. The wine is garnet in color with a clean and elegant nose that evokes ripe red and black fruits, raspberry, cherry, blackberry, blueberry enriched by fine woody notes, roasted coffee, cocoa and a hint of licorice.

*click on image for more info

Gouffier, Mercurey Lieu-dit ‘Les Murgers’ 2019 ($41)

Gouffier, Mercurey Lieu-dit ‘Les Murgers’ 2019 ($41)

‘Murgers’ refers to the stones that were removed from the plot to enable vine planting; the three-acre, east-facing Gouffier plot is rich in loamy topsoil with deeper layers of clay that relies on deeper rocks to supply adequate drainage. Vines are pruned according to the Guyot Poussard method, which takes sap flow into account and reduces the damage that pruning may cause. The wine’s forward bouquet of cherries and raspberries are touched with sweet soil tones and subtle hints of smoke girded by silky tannins and integrated acidity.

*click on image for more info

Gouffier, Mercurey Lieu-dit ‘La Charmée’ 2019 ($40) As charmed as this particular parcel may be, the name refers to the hornbeam trees (charmoie) that once grew in the spot. At just under two acres, the named vineyard (lieu-dit) faces east and contains ample loam and iron-rich ocher clay—the substance from which ocher pigment is made. Dark ruby in color, the wine offers rich raspberry, blueberry and toast on the nose with pepper hints on the finish.

Gouffier, Mercurey Lieu-dit ‘La Charmée’ 2019 ($40) As charmed as this particular parcel may be, the name refers to the hornbeam trees (charmoie) that once grew in the spot. At just under two acres, the named vineyard (lieu-dit) faces east and contains ample loam and iron-rich ocher clay—the substance from which ocher pigment is made. Dark ruby in color, the wine offers rich raspberry, blueberry and toast on the nose with pepper hints on the finish.

*click on image for more info

Domaine Michel Juillot

The vineyards of Domaine Michel Juillot spread across the Côte Chalonnaise and Côte de Beaune and include 50 acres of Pinot Noir and twenty-five of Chardonnay. Of the sites, located in twenty individual appellations, half are Grand Cru and Premier Cru. Says fourth-generation winemaker Laurent Juillot: “Between our parcels, we do not differentiate the care we provide. We are convinced that our added value is in the terroir alone. The difference between a Grand Cru, a Premier Cru, a Village or a Bourgogne generic wine comes from the soil, the earth, the sun and the grape in its environment. We respect them all equally and treat them accordingly.”

Laurent is the grandson of Michel Juillot, and it was with the elder Juillot’s blessing that the estate, under Laurent’s direction, began to move toward sustainable agriculture. As a true gauge of quality, he ferments on native yeasts alone, as he believes that this is the only way to faithfully transcribe into a single-parcel cuvée the true expression of that unique climat. Current production is 180,000 bottles.

Domaine Michel Juillot, Mercurey Blanc Premier Cru ‘Clos des Barraults’ 2019 ($45)

Domaine Michel Juillot, Mercurey Blanc Premier Cru ‘Clos des Barraults’ 2019 ($45)

Michel Juillot has the largest holding in des Barraults and produces the most well-known Pinot Noir bottling from the site, but Chardonnay vines make up about 36% of the ‘Clos’ plantings. The vineyard boasts classic Burgundian clay-limestone marl soils with a high proportion of lightly-colored gravel and pebbles in the topsoil. The southern exposure ensures good ripening, perhaps at the expense of prolonged time spent in the softer morning sun. Although Mercurey white wines generally take a back seat to the reds, this one offers Meursault-like creaminess with a backbone of crisp citrus and a vanillin finish.

*click on image for more info

Domaine Michel Juillot, Mercurey Premier Cru ‘Clos des Barraults’ 2019 ($45)

Domaine Michel Juillot, Mercurey Premier Cru ‘Clos des Barraults’ 2019 ($45)

18 months in oak barrels specifically built for this producer, 30% of them new. This shows in the soft wood undertone that follows the palate through raspberry jelly, spicy Morello cherry and pleasant leatheriness that arises from the integrated tannins.

*click on image for more info

Domaine Michel Juillot, Bourgogne Rouge 2019 ($29)

Domaine Michel Juillot, Bourgogne Rouge 2019 ($29)

An ‘entry-level’ Burgundy may come from numerous villages, each with a specific profile to add, but this one is unusual in that the vines used to produce the wine range from 26 to 41 years in age, adding a gravitas not often found in the basic Bourgogne designation. Aged 12 months in oak, the wine shows tart cranberry and hints of strawberry, with a subtle minerality behind a medium-weight Pinot Noir.

*click on image for more info

Domaine Adélie

Domaine Adélie, comprising 20 acres of various Mercurey lieu-dits (including the Premier Cru Champ Martin), was named for the daughter of Albéric Bichot, lead négociant at the famous Hospices de Beaune and owner of five other prestigious estates in Burgundy. He was voted best winemaker by the International Wine Challenge in three of the past ten years.

With this recognition comes a commitment to sustainable agriculture and a reverence for the uniqueness of each parcel and its stewardship. Despite the accolades, Albéric downplays the grandeur of his hallowed vineyards, preferring to talk about wine as a beverage to be enjoyed with friends, not over-analyzed or intellectualized.

Domaine Adélie, Mercurey Lieu-dit ‘en Pierre Milley’ 2019 ($50)

Domaine Adélie, Mercurey Lieu-dit ‘en Pierre Milley’ 2019 ($50)

From a 5-acre lieu-dit where the vine age averages 35 years, the soil is rich in clay above a bedrock that consists of compacted limestone with a few areas that are predominantly marl. The nose shows forward fruit with notes of wild berries, plum and peach while the velvety and smooth with a long, nicely balanced finish.

*click on image for more info

Domaine Faiveley

The Faiveley family has been present in the Côte Chalonnaise for four generations and in Mercurey since 1963, the year that Guy Faiveley planted the vines that are still producing today. These vines are found in five distinct climats and cover nearly a hundred acres. Grapes are hand harvested, sorted and pressed on site in Mercurey, and after vinification the young wines are brought to the domain cellars in Nuits-St-Georges for aging. The wine is aged in a combination of stainless steel and oak for 12 to 14 months prior to release.

Domaine Faiveley ‘Vieilles Vignes’, Mercurey 2019 ($43)

Domaine Faiveley ‘Vieilles Vignes’, Mercurey 2019 ($43)

From a 67-acre plot with vines planted in 1962, 1978, 1981. Elegant and charming with aromas of raspberries and plums mingled with sweet spices and raw cocoa. Medium to full-bodied, bright and fleshy, with lively acids and velvety tannins.

*click on image for more info

- - -

Posted on 2022.04.08 in Côte Chalonnaise, Mercurey, France, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Aglianico, Albarino, Albarín Tinto, Alicante Bouschet, Aligote, Altesse, Arbanne, Arcos, Auxerrois, Barbarossa, Beaune, Biancu Gentile, Bonarda, bourboulenc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Chenin Blanc, Cinsault, Clairette, Cortese, Corvinone, Cot, Counoise, Dolcetto, Erbamat, Fiano, folle Blanche, Fumin, Gamay, Garganega, Garnacha Tintorera, Godello, Graciano, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, Grolleau, Groppello, Jacquère, Juan Garcia, Lladoner Pelut, Macabeo, Maconnais, Malbec, Malvasia, manseng, Marcelan, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Melon de Bourgogne, Mencía, Merlot, Montepulciano, Montònega, Moscatell, Mourv, Mourvèdre, Muscadelle, Muscat, Natural, Nebbiolo, Nero d'Avola, Niellucciu, Palomino, Parellada, Patrimonio, Pecorino, Pedro Ximénez, Persan, Petit Meslier, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Auxerrois, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Pouilly Fuisse, Pouilly Loche, Riesling, Rousanne, Sagrantino, Sangiovese, Sauvignon, Sciacarellu, Semillon, Serine, Sumoll, Tempranillo, Teroldego, Timorasso, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, trepat, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, Vermentino, Viognier, Viura, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012