| Saturday Sips returns March 5, 2022 with a tasting of several wines from the Henry Marionnet selection. As always, we place safety at the forefront of wine tasting experiences, and whereas we will provide glassware, feel free to bring your own if it makes you feel more comfortable. |

|

Loire Valley: Diversity of Wines

|

|

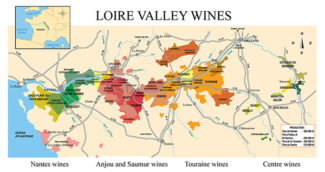

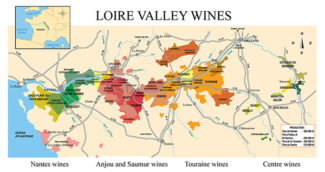

| The wild Loire is the longest river in France, and its associated winemaking region covers more than 185,000 acres. Originating in the deep south—virtually in the Rhône appellation—the river scrambles up through Orléans and hooks over toward Tours in the country’s heartland. It’s here, in central France, in the northeastern limit of the Loire Valley, that the appellation’s anointed whites are born.

But the heart of the region—Chinon—is red, and produces blood-rousing wines saturated with iron-tinged summer berries and often touched with elusive herbal notes like mint, tobacco and green peppercorn, the signature of Loire’s main red variety, Cabernet Franc. |

|

But there’s another red grape variety grown in Central Loire; the one that Philippe de Bourgogne cast out of Burgundy with his scathing edict six centuries ago. Gamay is grown in small quantities and used primarily for rosé or to lighten up blends. In Touraine, however, Gamay is capable of producing monovarietals of note, and the best of these (arguably) come from a single producer.

| The city of Tours sits half-way between Sancerre and Nantes and lends its name to the regional appellation ‘Touraine,’ home to about 12,000 acres of vineland. 59% of Touraine production is white predominantly made from Sauvignon Blanc and Chenin Blanc; reds account for 22%, led by Gamay, grown in 21% of Touraine vineyards. Rosé represents 8% of the region’s output and sparkling, another 11%. |

|

The Touraine appellation follows the Loire for roughly 60 miles; from Blois in the east to Chinon and Bourgueil in the west. Beyond this, the river continues into adjacent Anjou. Sandwiched between the Atlantic Ocean and the northern Massif Central hills of central France, Touraine’s climate falls somewhere between maritime and continental. The favored vineyard sites are those featuring free-draining, tuffeau-rich soils, and throughout the region, ‘tuffeau’ is the magic word. It is the calcareous rock that forms the foundation for Loire terroir and makes a marvelous building material for most the valley’s famous châteaux. Not only that, but tuffeau caves provide perfect conditions for long-term wine storage and ageing.

Domaine de la Charmoise

(Jean-Sébastien et Henry Marionnet)

|

|

| Over the centuries, many popes have passed through Loire (the Château de Chambord, the region’s grandest manor, contains private papal apartments) and Henry Marionnet applies the job description to oenology, reckoning himself an honest man making honest wines.

And by that he means natural wines, grown without pesticides and vinified without sulfur or oak. As he explains it, “My family has owned Domaine de la Charmoise since 1850; my father Claibert was a winemaker, of course, and I was expected to follow in his footsteps. But I never attended viticulture school—my parents were traditionalists and they didn’t want me coming back with revolutionary ideas. Therefore, my winemaking education involved working with the horses ploughing and clearing, and with a pickaxe, working the ground between the vines by hand. When I took over the domain in 1967, I began to change things. Some of the vines I inherited were of questionable merit, hybrids or similar sub-standard stock, so I set about replanting and expanding the vineyards. But I remained true to the words of the great Émile Peynaud who said, ‘Give me the most beautiful grapes in the world and I will make you the greatest wine in the world’.”

The vines of Domaine de la Charmoise—150 acres mostly dedicated to Sauvignon Blanc and Gamay—grow at the highest point between the Loire and Cher rivers, where a combination of situation and geology provides plenty of sunshine and shelter against spring frost.

Having recently succeeded his father in managing the estate, Henry’s son Jean-Sébastien has brought his own perspective to Domaine de la Charmoise, expanding the range to include Côt (Malbec) and Chenin Blanc as well as some Loire’s rarest varietals. To be sure, however, Henry’s presence is still widely felt. |

|

This 8-bottle pack, at $196, contains two of each of the following four wines.

Sélection Massale: Diversity in Vines

|

|

| Like skirt length and the width of ties, outdated viticulture techniques occasionally find favor among a modern generation. In the 1960s, UC Davis researchers developed a method of treating imported vine cuttings to clean them of disease and viruses, and then registered them as clones. Much of the wine we enjoy today (Pinot Noir Clone 777, Cabernet Sauvignon Clone 6, for example) is the result of this work, and since then, most new vines are purchased from vine clone nurseries—a method known as clonal selection.

The issue with clonal selection is that the wines tend to be somewhat homogenous—and that is the arch-enemy of the unique expression that is sacred to the French concept of terroir. The older, more labor-intensive method of propagation is Sélection Massale (or Massal Selection), which involves replanting new vineyards with cuttings from exceptional old vines from the same, or nearby properties. This method results in vineyards that appear less uniform and produce slightly smaller yields, but by virtue of genetic diversity (varietals mutate fairly easily) there is greater disease resistance.

Jean-Michel Cazes, owner of Château Lynch Bages and Château Les Ormes de Pez, champions Sélection Massale: “Our older vines represent decades of observations, adaptations and optimization and their genetic diversity leads to less exposure to catastrophic disease or adverse condition that might gravely affect a cloned vineyard. We use only cuttings from only our top vines; it’s a long-term and highly time-consuming process, but one that is well worth the effort both for safety and quality.” |

|

Domaine de la Charmoise ‘Sauvignon’, Touraine 2018 ($19) WHITE

Domaine de la Charmoise ‘Sauvignon’, Touraine 2018 ($19) WHITE

100% Sauvignon Blanc, hand-picked, hand-sorted, fermented without added yeasts, then aged for a year in stainless steel vats before release. The flint in the soil translates to a slight smokiness on the palate along with spring flowers, lemon, pineapple and grapefruit. The finish is restrained and elegant with softer acidity and more complexity indicative of slightly longer skin contact.

Domaine de la Charmoise ‘Gamay’, Touraine 2020 ($20) RED

Domaine de la Charmoise ‘Gamay’, Touraine 2020 ($20) RED

The Gamay originates in 80 acres of vines planted between 1967 and 1978. The soil is stony, flinty clay combined with silica which warm up quickly and is known locally as ‘perruches’—a word that translates directly as ‘parakeets.’

A perfect spring-summer wine, best served with a slight chill; the lovely raspberry color is reflected in a refined nose and juicy palate, with notes of violet, peony and carbonic red fruit syrup. The freshness of the fruit persists through a long finish.

The Raw ‘Natural’ Gesture: All About Purity

|

|

| As in the world of popes, in the world of wine, irony abounds. One of the more noteworthy ironies in this week’s offering is that Domaine de la Charmoise nestles deep with the forests of La Sologne, home to the great Limousin oak trees that makes the best of French wine barrels. But the Marionnets, both father and son, eschew wood as ‘unnatural’ in their winemaking process.

Raw or ‘natural’ wine is unadorned; in its purest form, it is wine made from unadulterated fermented grape juice and nothing else. After all the Loire is a place where the purest French is spoken.

Winemaking consists of two steps; growing grapes and fermenting juice. Proponents of natural wines understand that the purity mission begins in the vineyard, so do not spray vines with pesticides or herbicides and handpick grapes instead of relying on machines to harvest them. Only ambient yeast is used in fermentation, and the wine is generally bottled unfined and unfiltered, occasionally leading to a slight cloudiness in the finished product. Sulfur is a bone of contention among natural winemakers, although its use does not necessarily disqualify a wine. As an additive, sulfites serve to preserve and stabilize wine as an assurance that the wine you drink tastes roughly the same as it did when it went into the bottle. Small amounts of sulfites (around 10 to 35 parts per million) may be considered acceptable to natural wine adherents, since that amount is ten times lower than the maximum allowable addition for ‘conventional’ wines in the United States, 350 parts per million.

As might be surmised, ‘Zero-Zero’ wines contain none at all, and are neither filtered nor fined, giving rise to the name: Nothing is added and nothing is taken away. |

|

Henry Marionnet ‘Première Vendange’, Touraine 2019 ($23) RAW RED

Henry Marionnet ‘Première Vendange’, Touraine 2019 ($23) RAW RED

As defined above, this scrumptious wine is not quite a zero-zero, undergoing a light filtration just prior to bottling. Otherwise, it is whole-cluster fermented in cement without sulfur, non-indigenous yeast or pigeage—a French term meaning ‘to punch down the cap.’ (When crushed grapes ferment in vats, the skins rise to the surface to create a thick cap that may or may not be punched down.) Punch-down is not done here, and the result is a wine that is arguably more complex than is typical for a Gamay, largely because without sulfur, the yeasts have a longer time to work and release secondary aromas and flavors. The wine is medium ruby in color with aromas of plum, cherry, dried flowers, and spices, dry on the palate with moderate tannin and acidity, and additional notes of grilled meat and forest floor.

Ungrafted Vines: Back to The Roots

|

|

| As even a moderately informed wine drinker knows, phylloxera—an aphid-like insect that feeds Vitis vinifera rootstocks, stunting growth of vines or killing them—decimated the French wine industry in the late nineteenth century. Accidentally brought to Europe by Victorian-era botanists via American vines, the infestation killed 915,000 acres worth of vines, representing more than 25% of France’s total. By 1895, French wine production was halved.

The solution wound up being in the country that caused the fuss in the first place; Vitis berlandieri is a native American variety whose roots are not only resistant to the pest, but are able to thrive in the calcareous soil that underlies much of France’s most prized vineyards. A vast program of grafting saved the French industry, but some purists insist that it signaled the end of French wines themselves.

Is there a difference between wine grown on different rootstocks? “Wines from ungrafted vines tend to show a little more mineral, herbal and tertiary characteristics” says Daniel Callan, a winemaker from California, while Nik Weis, owner of St. Urbans-Hof Weingut is less ambiguous: “The indisputable greatness of ungrafted vines lies in their homogenous structure. They are not from two different pieces of wood, so there is no disturbance of the sap flow by a grafting cut. It is one, closed, plant system. It is the plant the way nature or God created it, original and non-manipulated, a true and pure cultivar. It is the best way to grow grapes and to produce great and authentic wines which reflect their regional character and provide maximum quaffability.”

In fact, although nearly all French vines are grafted, there were a few rootstocks which survived the phylloxera epidemic. Most of the vines have since died (not all, though), but their roots were used to propagate newer vines of the same type.

For Henry Marionnet, they are something of a specialty, and he has 15 acres given over to ungrafted Gamay, Malbec, Sauvignon Blanc, Chenin Blanc and Romorantin—a rare, late-ripening white wine grape. Marionnet claims that one plot of Romorantin dates to 1850, making them the oldest vines in France. |

|

Henry Marionnet ‘Renaissance’, Touraine 2018 ($36) RAW RED

Henry Marionnet ‘Renaissance’, Touraine 2018 ($36) RAW RED

From an ungrafted plot of Gamay planted in 1992, the wine is racy and elegant, powerfully ripe and full of black cherry and spice with a core of tannins that is softening comfortably behind a backbone of acidity. Emphasis is on natural minerality unmasked by barreling.

- - -

Posted on 2022.03.06 in Touraine, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Loire

Domaine de la Charmoise ‘Sauvignon’, Touraine 2018 ($19) WHITE

Domaine de la Charmoise ‘Sauvignon’, Touraine 2018 ($19) WHITE Domaine de la Charmoise ‘Gamay’, Touraine 2020 ($20) RED

Domaine de la Charmoise ‘Gamay’, Touraine 2020 ($20) RED Henry Marionnet ‘Première Vendange’, Touraine 2019 ($23) RAW RED

Henry Marionnet ‘Première Vendange’, Touraine 2019 ($23) RAW RED Henry Marionnet ‘Renaissance’, Touraine 2018 ($36) RAW RED

Henry Marionnet ‘Renaissance’, Touraine 2018 ($36) RAW RED