Enthroned At The Summit Of Larzac: Domaine de Montcalmès, A Languedoc Stand-out, Drinks Well In Its Youth And Shows No Weakness With Age + Recent Arrival Two Rising Stars From Larzac — Five-Bottle Package For $215

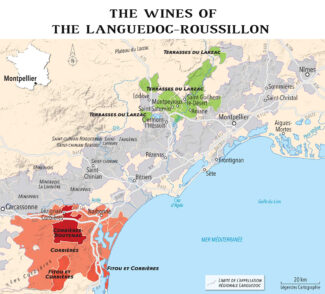

If you’re an aspiring domaine owner working with a tight budget, and have an eye to producing world-class French wine, you could do worse than Terrasses du Larzac, where an acre of vineyard land might set you back the equivalent of $5,000. Compare that to Burgundy’s $100,000-an-acre mind-blowing average. Not only that, but only 35% of the available land is currently under vine.

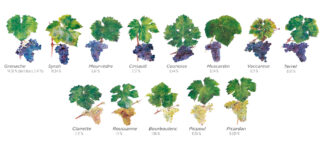

It’s no wonder that this relatively new (2014) appellation is seducing many winemakers who are equally green behind the ears; they are beginning careers with an eye (and palate) toward quality—still a rather novel concept in Languedoc, long the home for a sea of cheap wine available for under ten dollars a bottle. AOP rules in TdL are relatively tight in comparison to the Languedoc as a VdF: in Larzac, there are five permitted grapes—Grenache, Syrah, Mourvèdre, Cinsault and Carignan; the wines must be blends and include at least two from Grenache, Syrah and Mourvèdre. Furthermore, cellar-ageing must last at least one year.

Among the new class of Larzac producers, we number the following as among our favorites. They are visionaries with both heritage and discipline, finding in the wonderfully diverse terroirs of the region an opportunity to rival, and frequently outgun, wines from the same grapes made way up north in the Rhône.

Terrasses du Larzac: A Languedoc Stand-Out, Coming Into Its Own

The history of Languedoc’s vineyards dates back to the 5th century BCE when the Greeks introduced vines to the area. As such, the Terrasses du Larzac AOP is a bit anomalous simply because it only received official recognition in 2014. Extending across 32 communes among the foothills of Larzac, with its northern boundary naturally formed by the Causse du Larzac, part of TdL’s appellation upgrade was a phasing-out of the predominantly Carignan-based wines of the past in favor of ‘cépages améliorateurs’ (improver varieties) like Grenache, Syrah and Mourvèdre—grapes more usually associated with Rhône. Carignan is now limited to only 30% of any Terraces du Larzac wine.

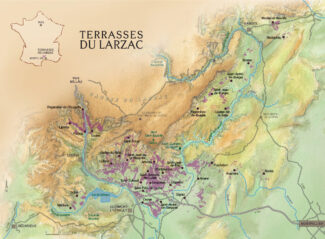

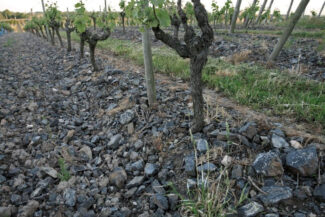

But the terroir is perfectly suited to the Big Three; Larzac is geologically varied and offers soils that range from stony clay and sand, iron-rich red soils, and heavier clay soils with high limestone content. Vineyards situated on the banks of the Hérault river are planted on pebble-strewn alluvial terraces and stonier soils with limestone bedrock. The average altitude of the local vineyards is around 400 feet, but rise to nearly 1300 feet in the northerly commune of Saint Privat. The Mediterranean climate provides distinctly seasonal rainfall throughout spring and fall, and thanks to the nearby mountains of the southern Massif Central, the appellation’s vineyards enjoy the benefits of cooler nights after hot days, helping to provide balance between sugar and acid in the grapes.

The Package …

This week’s package offering is comprised of five wines featured and numbered below: Two wines from Montcalmès, one red and one white, and one of each of Saint-Sylvester and Le Clos du Serres two wines for a total of five bottles at $215.

Domaine de Montcalmès

The Summit of Larzac

The quiet persistence of Frédéric Pourtalié has, since his first vintage in 1999, gradually elevated Domaine de Montcalmès to a quality level to match his mentor Grange de Pères, although in terms of cult wine status, it still flies a bit under the radar. Pourtalié trained at Pères before taking over family vineyards at the edge of the Massif Central, where cool night air descends off the Cévennes Mountains.

Named for a hamlet that once overlooked the Hérault valley, Pourtalié’s winemaking cousin Vincent Guizard (now of Domaine Saint-Sylvestre) joined in 2003 in a quest to put the Hérault estate on the world’s wine map. Today, Pourtalié farms 54 acres spread between the communes of Puéchabon, Aniane, St. Jean de Fos and St. Saturnin de Lucian, each with its own unique microclimate and soil geology. Montcalmès means ‘limestone mountain’ in Occitan, and Pourtalié draws variously from the lacustrine limestones of Puéchabon, the rolled pebbles of Aniane, the scree of Saint-Saturnin and the clays of Saint-Jean-de-Fos.

Frédéric Pourtalié, Domaine de Montcalmès

photo: Atelier Soubiran

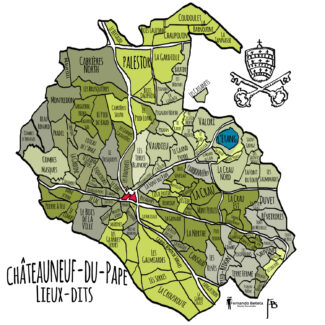

The domain is hundreds of miles from either Burgundy or Southern Rhône, but the influence of both manages to trickle down to Pourtalié’s operation. His Mourvèdre grows on pudding-stones nearly identical to Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s galets roulés and his red wines are aged for 24 months in old Romanée-Conti barrels, giving them a potential longevity of a decade or more.

Frédéric Pourtalié proudly shares that for the past decade, he has been supplying top-end wines to local Michelin starred restaurants— the Pourcel, the Auberge du Vieux Puits in Fontjoncouse, Michel Bras in Aveyron—but also the Troisgros, Pierre Gagnaire, the Grillon in Paris. “Between restaurants and a network of wine merchants, it is sometimes hard to keep up,” says Pourtalié.

“We are slowly expanding; I recently planted six acres of Syrah on a clearing of scrubland on the hillsides, but I’ve also made time to vinify a 100% Viognier in Vin de France, this time sold only in the cellar. A special vintage just for visitors.”

Vintage 2020

The ‘nutshell’ summation of the 2020 vintage in Languedoc is ‘low quantity, high quality.’

For the most part, the appellation had ample reserves of water from flooding the previous autumn and winter. The spring was quite cool, and there was quite a bit of rainfall in late April early May. Summer heated up, but not to the over-the-top extremes of 2019; it was dry, but the August nights were cool—ideal were quite warm but thankfully without the extremes of 2019. High summer did of course warm up and was dry as usual, but the August nights were cool with an ideal condition for the ripening and flavor development.

•1• Domaine de Montcalmès, 2020 Terrasses du Larzac ($57) – One Bottle

•1• Domaine de Montcalmès, 2020 Terrasses du Larzac ($57) – One Bottle

60% Syrah, 20% Mourvèdre, 20% Grenache; the grapes were destemmed and crushed and allowed to ferment separately on indigenous yeast during a maceration of 30 days. The varieties underwent regular punching down, following which barrel-aging took place over 24 months; the three varieties were blended two months before bottling.

The wine shows clean blackberry and cassis notes while the palate is silky with spice and fine-grained leather with a touch of licorice on the finish.

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2020 Languedoc Blanc ($58)

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2020 Languedoc Blanc ($58)

50% Marsanne, 50% Roussanne—the classic Hermitage blend in which the Marsanne provides body and the delicate flavors of peach, pear and spice, while Roussanne brings elegance, aroma, crisp acidity for aging and nut along with mineral notes. The vines, now over twenty years old, are located in Puéchabon on a clay-limestone hillside. After harvesting by hand, the two varietals were pressed and vinified together via direct pressing, and cold settled. Vinification occurred on indigenous yeasts in barrels and demi-muids and the wine was aged in used oak barrels for 24 months. The different barrels were blended 4 to 6 months before bottling.

•2• Domaine de Montcalmès, 2020 VdF Languedoc-Terrasses du Larzac Blanc ($47) – One Bottle

•2• Domaine de Montcalmès, 2020 VdF Languedoc-Terrasses du Larzac Blanc ($47) – One Bottle

40% Petit Manseng, 10% Gros Manseng, 10% Petit Courbu, 10% Gros Courbu, 15% Chenin, 15% Chardonnay; a blend so unusual it wears the generic VdF label, but don’t let that fool you; the wine is a gem, showing taut minerality and an herbal edge suggestive of the wild thyme and fennel that grow near the vines. In the mouth, it is reminiscent of honey, almonds, wildflowers and gentle brine.

Vintage 2019

2019 was (as is happening more and more frequently) a season of intense drought, beginning with a cold, dry spring which slowed leaf development in the vines. High summer temperatures arrived quickly and further slowed growth during peaks. Relief came in the weeks before harvest with a mercury drop, especially at night, and a few rain-filled days. Harvest 2019 came later than in 2018 and the wines are more concentrated, with nicely defined tannins behind moderate to low acidity.

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2019 Terrasses du Larzac ($57)

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2019 Terrasses du Larzac ($57)

60% Syrah, 20% Mourvèdre, 20% Grenache. The two sites that contribute to this are distinct; the first is north-facing and on limestone scree, the source of the Syrah and Grenache, while the second is south-facing and on galet roulés as you might find in Châteauneuf-du-Pape. This warmer site is where he sources the heat-loving Mourvèdre. The wine aged in old casks from Domaine de la Romanée-Conti for two years before release and reamins fresh on the nose with ripe plum and blackberry, bricking out with leather, balsamic, undergrowth, chocolate and dried fruit.

Vintage 2015

A delightful vintage for Languedoc; one that wine writer Jancis Robinson calls ‘une année vinabilis.’ Water tables were replenished over the previous year’s winter, and spring was warm and dry, with no weather issues during flowering. Conditions that favor healthy and clean fruit continued into summer, with no hail or rainstorms of any serious note. Hydric stress was an issue for younger vines with shallower roots, notably some Syrah planted in 2006. The older Grenache and Syrah shrugged it off as deeper roots found water. Harvesting began in early September and finished a week earlier than ever before. Grenache wound up as the star of the year; ripe, healthy and very juicy. The Syrah yielded smaller but very concentrated and fruity berries. The Mourvèdre and Carignan were well-balanced between acid and sugar.

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2015 Terrasses du Larzac ($48)

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2015 Terrasses du Larzac ($48)

60% Syrah, 20% Mourvèdre, 20% Grenache; an enticing nose displaying ripe black cherry, anise and a fleeting whiff of dried strawberry. A Grenache with a delicacy that is reminiscent of Château-Rayas; a nice balance between fruit and the grip of acidity and silken tannins.

Vintage 2014

As folks in Languedoc recall too well, 2014 was the vintage of cataclysmic hailstorms which seriously compromised yields. Spells of unseasonably hot spring weather tested vines while the summer brought sharp variations in temperature, with cool periods followed by periods of extreme heat. Only the most careful and persistent vintners produced notable wines, but the best of these show balance, concentration and complexity at relatively low alcohol levels.

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2014 Terrasses du Larzac ($50)

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2014 Terrasses du Larzac ($50)

60% Syrah, 20% Mourvèdre, 20% Grenache; the nose is full of leathery cherry and perfumed with dried violet while the fruit is settling into garrigue spice with a long and lingering finish washed in velvety tannins.

Vintage 2013

Compared with the rest of France, the Languedoc fared well in 2013, escaping most of the major climatic hazards that beset other regions. Key climatic factors were a wet spring—the wettest in thirty years—but that meant that there was no danger of water stress later in the season. Summer arrived late, leading to a late harvest—sometimes grapes catch up, but this year they did not. Fortunately, September was bright and sunny and the rain that did fall did not harm the grapes. They ripened well, with supple tannins and ample freshness.

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2013 Terrasses du Larzac ($49)

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2013 Terrasses du Larzac ($49)

60% Syrah, 20% Mourvèdre, 20% Grenache; a typically elegant wine in the process of aging beautifully, showing broad and expansive dried berries and kirsch accented by hints of garrigue and Asian spice. The finish is very long, with ripe, silky, fine-grained tannins.

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2013 Terrasses du Larzac ($130) Magnum

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2013 Terrasses du Larzac ($130) Magnum

A large format version of the above.

Vintage 2012

The most challenging vintage Languedoc had seen in 22 years. Yields were low thanks to drought at one stage and mildew at another, and late, uneven ripening resulted in many wines without fully-developed character. It was not a complete disaster, however, and top domains were able to produce a limited amount of excellent wine.

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2012 Terrasses du Larzac ($47)

Domaine de Montcalmès, 2012 Terrasses du Larzac ($47)

60% Syrah, 20% Mourvèdre, 20% Grenache. Polished and splendidly bricked-out, this elegant wine offers dark fruits, bittersweet chocolate and light notes of vanilla behind musk and five-spice powder.

RECENT ARRIVAL

Domaine Saint Sylvestre

Terrasses du Larzac, Languedoc

It’s easy to conclude that Terrasses du Larzac has one of the highest concentrations of ambitious young producers in the south of France. This is partially due to the unique climate conditions but also the vast range of soil types confined to a relatively small area. Throughout the communes that host Larzac’s vineyards, you’ll encounter schist, sand, horizontal layers of red ruffe, clay/limestone and galets roulés in the course of a few miles.

“Among the more interesting of these types is the ruffe,” says Vincent Guizard of Domaine Saint-Sylvestre, referring to the fine-grained, brilliant-red sandstone soil. “It’s rarely found outside Languedoc. It is extremely iron-rich soil that is a beautiful brick color and produces intense, fruity and full-bodied Syrah, Grenache, Carignan, Mourvèdre and Cinsault.”

Vincent and Sophie Guizard, Domaine Saint Sylvestre

Guizard knows his terroir as well as his wife Sophie knows the wine business; together, they created Domaine Saint-Sylvestre in 2010 with 17 acres he owned as part of Domaine de Montcalmès, the winery he worked alongside his cousin, Frédéric Pourtalié. Domaine Saint-Sylvestre released its first vintage release in 2011.

Vincent and Sophie employ a sustainable approach to viticulture, a method known as ‘lutte raisonnée’ (the reasoned struggle) and use no synthetic fertilizers or herbicides in the vineyards.

•3• Domaine Saint Sylvestre, 2015 Terrasses du Larzac ($39) – One Bottle

•3• Domaine Saint Sylvestre, 2015 Terrasses du Larzac ($39) – One Bottle

70% Syrah, 20% Grenache, 10% Mourvèdre. A beautifully-aged Larzac blend showing dried cranberry, sweet leather, crushed stone, garrigue and woodsmoke. Total production, 1375 cases.

Rich-iron red Ruffe soil

Le Clos du Serres

Terrasses du Larzac, Languedoc

Says Beatrice Fillon, “We chose this new occupation to rebuild their lives, to abandon a lifestyle where speed was of the essence and which seemed to us to be more and more unreal.”

She is referring to the decision she made with her husband Sébastien to purchase the 40-acre domain Clos du Serres. It was a life-changing move for the couple. Born in St Etienne, Sébastien grew up in a rural, agricultural environment and was familiar with working the land, but it was Beatrice, who hails from Montpellier, who chose the area: “We wanted to move south to the only region where there is still land to clear.”

Sébastien adds, “We were won over by the quality of life, surrounded by wild, unspoilt nature, set among olive groves, vines and the wild garrigue, close to some great natural sites—Lake Salagou, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, the Hérault gorges—but not far from Montpellier or the sea at the foot of the Larzac plateau.”

The Fillons, Le Clos du Serres

The domain is organically certified and the Fillon’s philosophy is built around the idea that a wine’s quality has its roots in the vine, but terroir gives nothing without being worked. To this effect, each of their parcels are cultivated with individual attention: “In winter, we leave the grass between the rows of vines to avoid erosion during the heavy autumn rain and enhance the soil’s life,” says Sébastien. “We start ploughing with the first warm days getting rid of the grass naturally thus ensuring it doesn’t challenge the vine’s access to water. During the winter we treat with organic material; grape-based compost and manure from animals bred on the Larzac plateau.”

Work in the cellar is equally meticulous, according to Fillon: “We use ‘tronconique’ (conical) concrete vats and other small ones made of glass fiber with floating ‘hats.’ Thanks to the shape of the concrete vats, the ‘marc’ hat sinks into the juices, resulting in soft and natural extraction, so that fermentation based on the grapes’ natural yeast is very steady. The glass fiber vats mean we can work with very small volumes, maximizing our ability to vinify parcel by parcel. Proof is that our winery boasts 17 vats for 15 land parcels.”

•4• Le Clos du Serres ‘Le Palas’, 2018 Terrasses du Larzac ($33) – One Bottle

•4• Le Clos du Serres ‘Le Palas’, 2018 Terrasses du Larzac ($33) – One Bottle

From a west-facing lieu-dit adjacent to the village of Saint-Jean de la Blaquière, this organically-certified blend of 38% Syrah, 32% Carignan, 30% Grenache is aged in concrete and shows blackberry and plum preserves with citrus notes accompanying licorice, black pepper and graphite. Total production, 250 cases.

•5• Le Clos du Serres ‘L’Humeur Vagabonde’, 2019 Terrasses du Larzac ($39) – One Bottle

•5• Le Clos du Serres ‘L’Humeur Vagabonde’, 2019 Terrasses du Larzac ($39) – One Bottle

70% Grenache, 15% Cinsault, 15% Carignan; this tiny production wine (whose name loosely translates to ‘The Wandering Mood’), shows ripe blackberry, cherry and blackcurrant behind hits of coffee and chocolate with an impressive spice finish touched with clove and violet. 125 cases produced.

- - -

Posted on 2024.02.17 in France | Read more...

Lure Of The Loire II: A Wide Range Of Red Varieties, Soils And Microclimates Allow For A Diversity Of Wines And Styles By Upstart Generation

The media engine behind French wine seems driven primarily by two wheels—Burgundy and Bordeaux—while the Loire is often relegated to third-wheel status. And it’s not from want of praise: The vivid, crisp, hauntingly aromatic and almost supernaturally focused wines of the Loire Valley are arguably the pinnacle of each particular varietal.

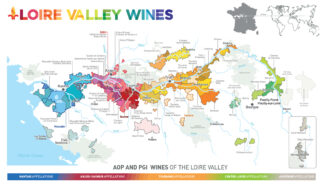

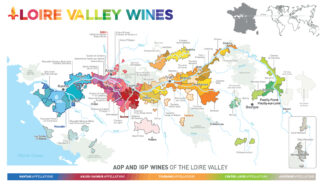

And there are many. 24 varieties flourish throughout the Valley (including indigenous, newly-revived grapes such as Pineau d’Aunis) alongside the Big Four, Melon de Bourgogne, Sauvignon Blanc, Chenin, and Cabernet Franc. The Loire Valley is the biggest producer of white wine in France and the second biggest producer of sparkling wines; it encompasses four sub-regions with more than 51 appellations surrounding the Loire River and its tributaries, flowing from the east around Sancerre to the west toward Muscadet on the Atlantic coast at the mouth of the river.

The Loire is also a hot-bed for experimental winemakers, some of whom have chosen to forgo the hidebound restrictions of the French wine bureaucracy and produce wines on their own terms, opting to use the all-encompassing Vin de France appellation on their labels rather than the prestigious AOPs they’d otherwise be entitled to. Lovers of natural wine know that the Loire was an early pioneer in the movement, and that such producers make wine with organic and/or biodynamic fruit, native yeasts, and a commitment to low-intervention viniculture as a bid for sustainability in the face of changing environment.

These upstart young winemakers have not only been flying under the mainstream radar, they have created their own generation of satellites—fans that recognize wine as an agricultural product as well as a cultural phenomenon, and are drawn to their dedication to natural farming.

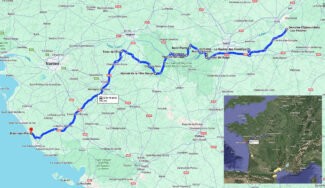

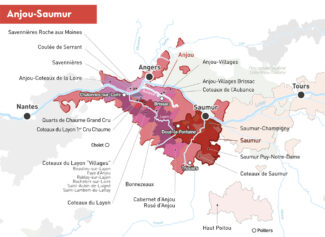

This week’s wine selection looks upward toward the light that vignerons in three specific Loire appellations—Anjou-Saumur, Touraine and Fiefs Vendéens—are shining on technique, innovation and originality.

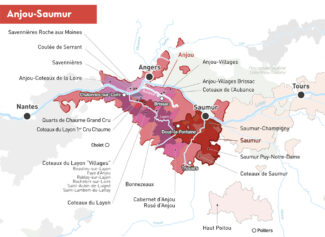

Anjou-Saumur: Driving a Full-on Revolution

In France, where plenty of revolutionaries wound up with their heads in a guillotine basket, ‘revolution’ is not a word to be used lightly. Still, Richard Leroy of Domaine Sophie et Richard Leroy in Bellevigne-en-Layon, Anjou, uses it easily: “There’s a revolution happening in wine right now,” he says, referring to Anjou, once an epicenter for sweet wines like Coteaux-du-Layon and Quarts-de-Chaume.

Over the past twenty years, Anjou has become a hub for a different kind of wine—those made with a minimum of artifice in the cellar, free from historical baggage about what they should taste like and often produced by first-generation winemakers with no family ties to wine.

Another phase of the revolution is the revival of Chenin, which fell out of favor during the second half of the last century as did the native red wine grape, Grolleau. Mark Angeli of La Ferme de la Sansonnière, who arrived in 1989, claims, “Dry Chenin had been gone from Anjou for 50 years, and the few reds being made were mostly rot-gut. Appellation rules required them to be made from the two Cabernets—Franc and Sauvignon—even though old-vine parcels of Grolleau and Pineau d’Aunis thrived throughout the area.”

The region has been attracting maverick winemakers who recognize the scant precedent for complex, dry wines made from Chenin and Grolleau, and who have been happy to bottle their rule-busting wines, farmed organically, under the relatively lowly ‘Anjou’ appellation or even labeled simply as ‘Vin de France.’

Touraine: The Original Breeding Ground of Pioneering Winemakers And Natural Wines

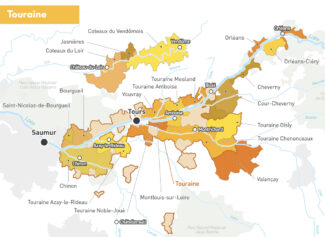

Most people are more familiar with the Loire’s bookends, Muscadet and Sancerre. But between them lie 79 AOPs representing what InterLoire (the official organization of producers, merchants and traders involved in the production and promotion of Loire wines) calls, “The most extensive, diversified and original vineyards in Europe.”

The AOP covering Touraine stretches from Anjou to the west to the Sologne in the east, converging near the point where the Loire River and its tributaries meet. It covers 104 communes in Indre-et-Loire and 42 in Loir-et-Cher.

Most of the vineyards are located southeast of Tours on the slopes that dominate the Cher River and the land between the Cher and the Loire. With nearly 13,000 acres under vine, the climate varies dramatically as you move inland; oceanic conditions dominate the west, becoming more continental as you move east. These climatic differences combined with varied soils determine the choice of grape variety planted (with later-ripening varieties grown in the west and earlier-ripening ones in the east) and account for the wide variety of wine styles produced.

Among these styles are the personal statement wines of natural winemakers, who have found in Touraine a vibrant opportunity for self-expression as well as terroir that, through minimal intervention, display their origins perhaps even more faithfully than their rule-bound AOP counterparts.

Cabernet Franc

Who’s your daddy? Biologically, both Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot share Cabernet Franc as a parent, and the grape itself displays characteristics inherited by both. In cooler climates, Cabernet Franc shows off graphite and red licorice notes, while in warm regions, it exhibits tobacco and leather aromas. There is also a vegetal edge, which may strike the palate as tasting of green pepper or jalapeño.

In Bordeaux, it is generally a minor component of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot blends, although in Pomerol and Saint-Émilion it adopts a larger, more highly-regarded role. Château Cheval Blanc, for example, is typically around two-thirds Cabernet Franc while Ausone is an even split between Cabernet Franc and Merlot.

With the Loire Valley’s cool, inland climates it becomes a star performer. The appellations of Chinon (in Touraine) along with Saumur and Saumur-Champigny (in Anjou) are important bastions of Cabernet Franc, where the wine is prized for forward aromas of ripe summer berries and sweet spices.

The local Loire Valley name for Cabernet Franc is Breton; a reference to the man credited with bringing the variety to popularity in the 17th Century.

Yannick Amirault (Touraine)

‘Fifty and out’ could be the mission statement of Domaine Y. Amirault, at least in terms of size. With around 30 acres in Bourgueil and 20 in Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil, Yannick Amirault has grown his vineyard space as large as he cares to, finding 50 acres to be the most he feels he can work to his exacting standards.

Having begun in 1977 with around ten acres inherited from his grandfather, Eugène Amirault, he was joined by his son Benoît in 2003. Yannick’s commitment to organic agriculture is not an attempt to hop on the bandwagon sweeping across French viticulture, but rather the opposite: “Weaning the vineyards off synthetic inputs—a process we completed in 1997—and following lunar calendar—may seem a bit trendy, but this is simply a return to the way Eugène Amirault made wine for his family.”

Yannick And Benoît Amirault, Yannick Amirault (Bourgueil, Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil) – (Photo © Jerome Paressant)

Benoît adds: “Harvest has always been done by hand and is initiated by many factors, all guided by combined experience. Each parcel is picked at its own optimal ripeness (and in several passes), then the grape clusters are transported to the cellar. Here, the work is both minimalistic and transparent: Grapes are sorted again and destemmed; fermentations are indigenous and conducted in large, open-topped, conical oak vats; macerations last up to sixty days with pigéage only at the very beginning and rémontage reserved only for the ripest vintages to reduce rustic tannins. Only the first press is used and is aged in neutral vessels—amphorae, oak demi-muids and well-seasoned vats.”

The result of this is a vibrant array of 100% Cabernet Franc wines, many reflecting individual plots across the two appellation; the domain has 25, some above the village on sands and gravels, others at the hill’s feet, in limestone.

“There is no terroir without the intervention of mankind,” says Yannick. “We look after our vines, year after year, as if it were a garden. We grow grass between vine rows and we plough the graveled plots which are more sensitive to a lack of water. Despite weather, our craft leaves nothing to chance. The pruning is Guyot-Poussard and vines through organic spraying of plants infusion. We also roll growing vines (we do not cut the top branches) on certain crus. Even in a low yield year, we do a growth clearing on all our vines in order to ensure an homogenous maturity of the grapes.”

Yannick Amirault ‘Le Grand Clos’, 2020 Bourgueil ($36)

Yannick Amirault ‘Le Grand Clos’, 2020 Bourgueil ($36)

Amirault owns five acres of the lauded, south-facing hillside Le Grand Clos lieu-dit, which is composed of clay and flint soils over tuffeau bedrock. Certified organic, his vines are 45 years old. The grapes are hand-harvested in successive passes, destemmed and allowed natural yeast fermentation in oak vats, and after four weeks of maceration, the wine is transferred to 400 liter French oak barrels for a minimum of one year. The wine is an earthy, black-fruit driven Cabernet Franc that shows the pencil-shavings graphite that are typical of the appellation, one of the few in Loire appellations to produce exclusively red wines.

Yannick Amirault ‘Les Malgagnes’, 2020 Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil ($42)

Yannick Amirault ‘Les Malgagnes’, 2020 Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil ($42)

Les Malgagnes is a hillside lieu-dit in the Bourgueil sub-appellation of Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil. It is slightly further down the limestone-rich slope than the other three lieux-dits on this particular côte. Amirault has six acres here, but only the fruit from the upper section, where the limestone is much closer to the surface, is used for this cuvée. The grapes see a four-week maceration with an élevage lasting 12 months in large barrels and demonstrate the silky elegance of old-vine Cabernet Franc grown in this pretty AOP; rich cassis notes are woven into fine-grained tannins and bittersweet chocolate on the finish.

Pierre Borel (Touraine)

The six-acre Clos du Pavée, where Pierre Borel has been making wine since 2006, is a true clos in the French sense, meaning that it a walled vineyard, once done to protect the grapes from theft and now, to improve the mesoclimate. Pavée soils are gravel; the surrounding acres are generally built around clay/limestone.

“Terror dictates wine style,” Pierre explains, “and this terroir I believe is meant to produce more easygoing, fruit-forward wines.”

This concept ultimately led Pierre to uproot and replant the whole parcel, settling on four new acres of Cabernet Franc and two of Chenin. Doing all the vineyard work alone (and by hand) Pierre is a firm believer in organic viticulture, and although he doesn’t believe that the AOP system is necessarily a mark of quality, he views working within it a commitment to the winemaking traditions in the area.

Pierre Borel (Bourgueil)

The seclusion of Clos du Pavée works to the advantage of Pierre’s passion for organics. With the village on one side and woodland on the other, his acres are under very little threat from contamination from neighboring growers who aren’t playing by his rules. He believes that his wines represent the purity and typicity of wines from Bourgueil—and that is his goal.

“Simplicity is key,” he states. “I make only one wine, and vinify in as straightforward a way as possible. I work with sandy limestone/gravel soils that yields plush, herbaceous and fragrant fruit. I ferment in a simple chai that contains one large tank of stainless steel and one of fiberglass. The wine is racked off the skins after a couple of weeks of maceration and is bottled from tank, with no barrel aging.”

He is also pleased to note that as his new vines mature, they are producing more complex and nuanced wine with each passing vintage.

Pierre Borel ‘Clos de Pavée’, 2019 Bourgueil ‘natural’ ($33)

Pierre Borel ‘Clos de Pavée’, 2019 Bourgueil ‘natural’ ($33)

Bourgueil is the heartland of Cabernet Franc in the Touraine district, and Borel’s five gravelly acres in Clos de Pavée are the epicenter of Bourgueil. This savory, natural red is replete with the meatiness that develops in Cab Franc under ideal condition, and here it is offset by crunchy cranberry and rich herbaceous notes. There is dark chocolate on the finish now, but the wine is structured to mature for at least another decade, and should develop the truffle-like savory tones.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge (Anjou-Saumur)

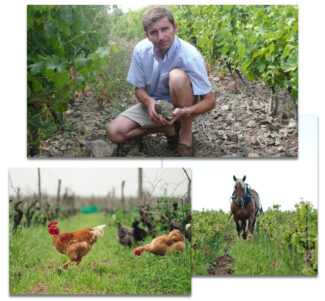

Intense, driven and passionate, Guillaume Reynouard is the fox in charge of the chicken coop—as well as being a winemaker, he is president of the Syndicat des Vins Saumur and has a particular enmity for growers who rip out Pineau d’Aunis in favor of easier-to-grow varieties.

Taking charge of Domaine Manoir de la Tête Rouge in 1995, Guillaume soon converted to organics and was certified Biodynamic in 2010. The estate enjoys remarkably productive clay/ limestone terroir and he takes pride in ‘living vineyards’ where the soil is worked by hand to ensure that roots go deep and grass grows between rows to promote insect and other plant life; synthetic chemicals are prohibited. In the cellar, grapes are fully destemmed, indigenous yeasts are preferred, with no additions and very minimal sulfur use.

Guillaume Reynouard, Manoir de la Tête Rouge (Saumur, Saumur-Champigny)

According to Reynouard, “Responsible agriculture is a way of life and of thinking. When growing grapes, I aspire to act sensibly for the planet—a state of mind that develops naturally from a respectful relationship with nature. Knowing how to adapt to a changing environment requires constant questioning while the planting of forgotten varieties such as Pineau d’Aunis, the incorporation of trees into the cultivation of the vine (agroforestry) and the gradual abandonment of ‘modern’ oenology are avenues that I have followed for more than 20 years.”

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘l’Enchentoir’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ‘natural’ ($43)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘l’Enchentoir’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ‘natural’ ($43)

In the sub-appellation Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame, ‘l’Enchentoir’ is a venerable Cabernet Franc lieu-dit. Planted over Turonian limestone in 1959 using sélections massales, the pressed wine is aged in 300-liter barriques for one year plus another six months in Béton cuves (pre-cast concrete tanks). It displays depth and delicacy, showing blackberry and cherry over violets, rose petals and savory herbs.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Tête de Lard’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ($27)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Tête de Lard’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ($27)

100% Cabernet Franc from two parcels averaging 20 years of age, ‘Tête de Lard’—Head of Bacon’—is fermented on native yeasts and spends a year in used 300-liter barrels. The final blend is done in concrete tanks, where the wine rests for 4 months before bottling. Filled with ripe tones of blueberry and cassis with a slight vegetal edge, this is a natural wine suited for the cellar, but one that should be tasted every couple years to keep an eye on the progress.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Bagatelle’, 2020 Saumur Rouge ($21)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Bagatelle’, 2020 Saumur Rouge ($21)

A bagatelle is something easy; something that requires little effort. This is not a comment on the precision that is de rigeur in Guillaume Reynouard’s winemaking, especially since the tech sheet for this wine specifies the terroir as 30% Jurassic limestone, 60% Turonian limestone and 10% silt, and the vines as being pruned in alternating Guyot-Poussard. Rather, the wine itself is created simply and naturally, macerated three weeks without yeasting, without chaptalization and without additives, then matured without sulfur. These minuses equal an ultimate plus; a pure Cabernet Franc with aromas of plum, raspberry, and cherry with notes of red pepper, spice, and graphite with silky tannins and bright acidity.

Terre de l’Élu (Anjou)

For Charlotte and Thomas Carsin, winemaking is many things—an interest, then a passion, then a commitment, then a profession. But first and foremost, it’s an adventure.

“My path to Clos de l’Élu began as a grape picker in Burgundy,” Thomas shares. “I was studying tropical agronomy, but ultimately chose to specialize in wine and found work placements in Sonoma, where I learned a great deal about terroir and vinification.”

After that, he learned the retail side of the business in a Paris boutique and spent five years doing consultancy work in Champagne. By the time his stint as a journeyman was over, he had arrived at a very keen personal opinion of the ‘overengineered’ wine industry: He hated it.

Thomas and Charlotte Carsin, Terre de l’Élu (Anjou)

By then he was well-versed in ‘winegrowing empiricism’—the language of the vines and master the idea of terroir. He spent a few more years making wine in Provence, in the département du Var, but it wasn’t until 2008 that he was able to acquire a domain and produce wine on his own terms: “Acquiring Clos de l’Élu, in the heart of the Layon valley, was a dream come true.”

Charlotte’s road to the winery was a bit more straightforward. Having worked in communication with specialized interest in pairing food and wine, she has learned the technical angles hands-on. Of course, her professional chops allow her to serve as the wineries administrator, in the sales and marketing of the winery, and especially brand image, packaging, events, and communication methods.

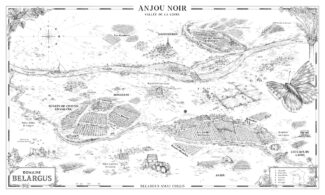

As to the estate, Terre de l’Élu is in Saint Aubin de Luigné; the vines grow on the outskirts of the village between Chaume and Ardenay, on the right, south-facing side of the Layon River. Soils here are classic Anjou Noir, full of volcanic rocks, sandstone and quartz.

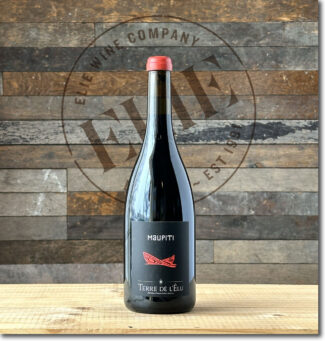

Terre de l’Élu ‘Maupiti’, 2021 VdF Loire-Anjou Rouge ($26)

Terre de l’Élu ‘Maupiti’, 2021 VdF Loire-Anjou Rouge ($26)

Thomas and Charlotte Carsin may have thrown a dart at a map of French Polynesia and landed on the tiny island of Maupiti to name this wine, which they describe as ‘approaching like a mysterious island amid the languor of oceans; you want to explore.’ A blend of 30% Gamay and 70% Cabernet Franc from vines between 25 and 40 years old, the grapes are whole-cluster-fermented separately on native yeasts and only blended after the completion of malolactic. The wine retains the brightness of Anjou Gamay, showing vivacious raspberry aromatics and the solid savory core of Cabernet Franc.

Le Sot de l’Ange (Touraine)

Although the label’s name roughly translates to ‘Idiot Angel’, winemaker Quentin Bourse is anything but. Before taking over a friend’s estate in time for the 2013 vintage, Bourse worked in various fields (some wine related; others not) including numerous internships in the surrounding area. Having learned technique from both natural and conventional producers, notably a six-month stage at the famed Vouvray producer Domaine Huet, his winemaking philosophy was shaped by philosophy and a relentless work ethic that leans toward innovation and the sort of perfectionism that is often at the root of natural wines—at least the ones that shine.

Unusual for the neighborhood, Bourse’s estate is certified biodynamic. Ranging across 30 acres, he is especially attracted to indigenous varieties that capitalize on the clay and silica soils for which the region is famous. In many of his parcels, white silex stones litter the rows making it look as if the terroir is seeping from the earth.

Quentin Bourse, Le Sot de l’Ange (Touraine)

He shares a cellar with old-school producer Pascal Pibaleau, where his grapes are painstakingly sorted four times before whole-cluster fermentation with indigenous yeasts in tank, and then a slow, gentle pressing that in some cases lasts five or more hours. Aging occurs either entirely in tank, neutral barriques, or amphorae depending on the cuvée, and zero sulfur is added during the winemaking process for the reds; a touch is added for the whites.

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Karadras’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine Cabernet Franc ‘natural’ ($24)

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Karadras’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine Cabernet Franc ‘natural’ ($24)

‘Karadras’ is 88% Cabernet Franc and 12% Côt; the name proves to be somewhat inexplicable since it appears in different spellings on different bottlings. What remains the same is that after being manually destemmed in wicker baskets, the fruit ferments in open wooden tanks and comes out the other end with a classic profile; a bit of color from the Côt, herbaceous notes from the Cab Franc. It offers dusty plum, soil, cocoa, and brambles; the palate is lively and fresh, lifted by crunchy acidity framing the ripe high-toned blue fruits, juicy plum and earthy spices.

Côt

‘Côt by any other name would smell like Malbec.’ With apologies to the Bard, the renaissance of this dark, potent grape in the Loire sees a remarkable change in profile. In southwest France—Cahors in particular—the variety produces heavy wines that are not only amenable to long periods of aging, they virtually demand it. In the Cher Valley, in the heart of Touraine, the grape finds a kinder, gentler environment where it produces a different sort of wine; less aggressively tannic with fresh aromas of black cherry and cassis. In part, it is the climate, but the fiercer aspects Côt as they appear in Cahors’ ‘black wines’ are tempered in the field, where vines are pruned short with a vendange vert after véraison. To avoid the additional tannins of oak, most of the grapes are fermented and aged in stainless steel tanks with a few barriques blended in.

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Le Jardin’, 2018 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘Côt’ ‘natural’ ($45)

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Le Jardin’, 2018 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘Côt’ ‘natural’ ($45)

100% Côt from an interesting lieu-dit with two distinct soil types—one section with clay and silex soils and the second with clay and limestone. The wine is vinified using whole-cluster fermentation in concrete tank; malolactic fermentation and élevage occur in terra cotta amphorae for 24 months. The wine shows aromas of freshly-picked bramble fruits, blackberry and currant, with slight Szechuan pepper notes and a touch of clove; a fresh, gripping palate.

Le Rocher des Violettes (Touraine)

Louis Barruol is known to be a tough taskmaster; he is the legendary Château de St-Cosme winemaker who transformed the family’s Gigondas estate from an anonymous bulk-wine source to the top winery in Gigondas—arguably into one of the best estates in the Southern Rhône. It is here that Xavier Weisskopf, founder of Le Rocher des Violettes (in 2005) went to work after studying winemaking in Chablis and Beaune and earning his degree in viticulture and oenology.

At Château de St-Cosme, Weisskopf rose to the rank of Chef de Cave, making four vintages during his tenure there. But he recognized that Rhône was not the best spot to grow his pet grape, Chenin, and that Montlouis-sur-Loire was. In 2005, he was able to purchase a site of old Chenin vines, many planted before World War II, in Montlouis, as well as Côt vines in Touraine, and he settled in to produce wines that allowed his new terroir to speak with clarity. This involved converting the farming practices to organics and extending the philosophy of ‘tradition’ to the cellars.

Xavier Weisskopf, Le Rocher des Violettes (Touraine, Montlouis-sur-Loire)

“Since 2010, my wife Clémence has been a part of the adventure, excelling in the administrative and commercial side of the business,” he says. “We have an additional team who work according to the season. Among our projects, we have been involved in an attempt to restore old vines to their original condition. We have dug a cellar in our native tuffeau so that the wines may age in the best conditions; it is built on multiple levels so that our mechanical force is provided by gravity. The constant cellar temperature is between 13 ° and 14 °C, allowing for the thermal self-regulation of the Allier oak barrels during fermentation.”

Le Rocher des Violettes ‘Côt’, 2020 Touraine ($23)

Le Rocher des Violettes ‘Côt’, 2020 Touraine ($23)

From seven individual plots, the grapes are 80% whole cluster fermented and aged 14 months in neutral foudres. The Malbec nose is unmistakable—a powerful blend of sweet and sour cherry and country herbs that, given time to open up, reveals coffee, leather, black pepper, vanilla and tobacco.

Pineau d’Aunis

‘Riches to rags’ may well summarize the Pineau d’Aunis story. Once a popular and sought-after variety among royalty on both sides of the English Channel, it is now increasingly rare, and generally limited to rosés and the lighter reds of the central Loire.

Part of the grape’s fall from grace is the fact that it is simply a pain in the neck to grow. Prone to irregular yields, it is also highly susceptible to bunch rot and hyper-sensitive to the soil it is grown in, requiring a balance of clay, sand and gravel in order to produce a crop of much commercial value. It is only in seasons of prolonged heat that it is capable of making red wine as distinctive and interesting as that made from the more ubiquitous Cabernet Franc.

And yet, of late, warmer seasons is exactly what has been happening in the Loire and as the more experimentative winemakers of the region are discovering, the dry reds made from the grape under optimal conditions show how presentable Pineau d’Aunis can be at the table of either kings or pawns.

Terre de l’Élu ‘Espérance’, 2021 VdF Loire-Anjou ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ ($47)

Terre de l’Élu ‘Espérance’, 2021 VdF Loire-Anjou ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ ($47)

100% Pineau d’Aunis from a variety of vine ages (seven years to 60), grown on rocky clay and schist. The grapes are allowed two weeks to macerate whole-cluster in stainless steel; they are then pressed and aged in neutral oak as fermentation completes. The wine is bottled with a minimum of sulfur and no fining. It shows the floral nose and spicy, fleshy body associated with this ancient grape; dried violet opens to raspberry and spiced cherry with a bit of crushed stone toward the finish.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘K’ Sa Tête’, 2020 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ Guillaume Reynouard ($27)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘K’ Sa Tête’, 2020 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ Guillaume Reynouard ($27)

100% Pineau d’Aunis from the lieu-dit de l’Enchentoir where soils are treated using Maria Thun’s biodynamic advice; this includes cow-horn dung in the spring and horn silica after closure of the cluster (a somewhat exacting process that is exactly what is sounds like, using cow-horns filled with manure and/or silica). Maceration lasts 12 days in concrete tanks without yeasting, chaptalization or additives. The wine spends six months in oak barrels and bottling is done in June with 20 milligrams of added sulfur. This is a textbook Pineau d’Aunis with black pepper and green pepper on the nose with a palate that expands to include sweet, perfectly ripe blueberries.

Grolleau

Grolleau is the Loire Valley’s workhorse grape, used most often in the production of rosé. Although it remains one of the Loire’s most planted red-wine varieties, new plantings have dropped steadily for the last 50 years. While Grolleau is high yielding, providing a steady, reliable harvest, it poses several challenges for growers as it is susceptible to disease and not a particularly flavorful stand-alone variety. It is a dark grape on the vine, but thin-skinned, meaning that there is not much chance for color extraction, so it is rarely used to produce red wines.

Grolleau-based wines tend to be high in acid, moderate in alcohol, and may show aromas of strawberry, raspberry and cherry; as a rosé, it is reminiscent of watermelon, tangerine, rose petals and red candy.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘À Tue Tête’, 2021 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Grolleau Gris’ Guillaume Reynouard ‘natural’ ($25)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘À Tue Tête’, 2021 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Grolleau Gris’ Guillaume Reynouard ‘natural’ ($25)

Vin de France is the most basic quality tier for wines from France, typically uncomplicated everyday drinks, likely blends, but occasionally are made from unlisted, unqualified varieties. Loosely translated to ‘loudly’, ‘À Tue Tête’ is a rare bottling from an even more rare variety, Grolleau Gris, which is a pink-skinned mutation of Grolleau. Handled with the biodynamic tool-kit, the wine shows red cherry, sandalwood and a bit of tropical fruit.

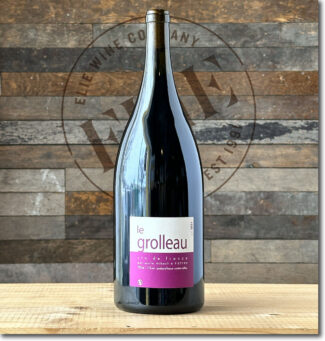

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘OG Grolleau’, 2020 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘natural’ ($39)

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘OG Grolleau’, 2020 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘natural’ ($39)

IGP (Indication Géographique Protégée) is a quality category used for French wine positioned between Vin de France and Appellation d’Origine Protégée (AOP). (The category superseded Vin de Pays in 2009.) Most significant in commercial terms is the fact that the wines may be varietals and labeled as such. ‘OG Grolleau’ comes from single parcel of old-vine Grolleau planted between 1945 and 1976; grapes are de-stemmed, given ten days of maceration, aged in amphorae and used oak barrels, then bottled without sulfur. Blueberry and violet dominate the nose while the palate resolves itself in a mineral crunchiness with beautiful acidity.

Domaine Marie Thibault (Touraine)

“I grew up in the Loire Valley, but unlike many vignerons working in the Loire, I did not come from a winemaking family,” says Marie Thibault, adding, “But also unlike many of them, I have degrees in both biology and oenology.”

Marie Thibault began making wine in the early 2000s, working for a time with François Chidaine in Montlouis, where she fell in love with Chenin. In 2011, she founded her own nine-acre estate on a single windy slope in Azay-le-Rideau, a lesser known commune of Touraine. She immediately converted to organics and has been certified with Ecocert since 2014. Among the natural elements in her vineyards is the flock of two dozen ewes that graze between the vine rows during the autumn; every ten days, they are penned inside a new hectare to keep the soil naturally fertile and the grass clipped.

Marie Thibault, Domaine Marie Thibault (Touraine) – (Photo © Jean-Yves Bardin)

“My vineyard is small, but the soils are extremely varied and as such, so are the grapes I grow. I work with Côt (Malbec), and have a special love for Gamay, Grolleau, Chenin and Sauvignon Blanc. Most of my vines are at least 50 years old. I compensate for small production by purchasing from organic estates nearby.”

Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Le Grolleau’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘natural’ ($89) 1.5 Liter

Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Le Grolleau’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘natural’ ($89) 1.5 Liter

A wine whose heritage is perfectly reflected in Thibault’s scant acres—Azay-le-Rideau is ground zero for Grolleau, first planted in early 19th century. ‘Le Grolleau’ is an ultra-fresh example made using Beaujolais-style carbonic maceration and held to a little over 11% abv, which solidly qualifies it as a ‘vin de soif.’ It is made using 60-year-old organic vines planted on hillsides on the southern slopes of the Indre—an early-ripening terroir filled with draining soils with a presence of flint, and bottled at the Estate in April 2022 without fining or filtration and just a micro-dose of sulfur. This wine is kept even fresher en magnum; it is fruity, juicy and velvety with sweet cranberry, blueberry, red plum, blueberry, cranberry, a touch of pepper with black cherry on the finish.

Gamay

Ever since Philippe de Bourgogne cast Gamay from the bosom of Burgundy six centuries ago, the variety has been derided and even despised outside its spiritual home, Beaujolais. Folks who were soured by the sweet and fruity Nouveau cult may bring that prejudice into Touraine, but that would be a mistake: Although once in the shadow of Anjou Gamay, select vignerons in Touraine have made monster strides with Gamay over the past couple decades and these wines now edge out the Gamays of Anjou in depth and complexity. They tend to be medium-bodied with a musky tone that share center stage with aromas of fern and capers intermingled with flinty minerals and plummy notes.

Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Les Grandes Vignes’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘Gamay’ ‘natural’ ($41)

Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Les Grandes Vignes’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘Gamay’ ‘natural’ ($41)

Thibault’s unique lens on Gamay is seen in this example produced from 50+ year-old vines she discovered growing adjacent to her plot on flinty silex soil. The vines were untrained and un-trellised, and harvest was exceptionally labor-intensive. She allows a 10-month maceration in order to shows off the Gamay’s savory side, with crisp rhubarb, earthy red berry notes and fine-grained, well-integrated tannins showcased.

Famille Percher (Touraine)

Perhaps the most interesting parcel farmed by Luc Percher (of Domaine l’Epicourchois) is ‘La Marigonnerie’ directly adjacent to the winery. In Napoleon times the vineyard area was a pond, and although the region sits on a bed of limestone sprinkled with granitic sand, the pond left behind a bed of clay which, about 120 years ago, was planted to Romorantin—a local white wine variety with its own appellation (Cour-Cheverny) where it is the only grape permitted.

Luc began making wine here in 2005. “When I arrived, the sand was as white as a beach. I fell in love with the ambience—a few wispy trees and an expansive horizon-line. It is quiet terroir.”

Luc Percher, Famille Percher (Cheverny, Cour-Cheverny)

His 22 acres of vines, tended with certifications from BIO and Déméter, is hardly restricted to Romorantin, although only his 100% Romorantin can be labeled Cour-Cheverny. His Sélection Massale old-vine vineyards contain ten different grape varieties, and some even more rare than Romorantin—Menu-Pineau, Gamay Fréaux and Chaudenay, for example. In order to maintain the biological heritage of these grapes, Luc is committed to soil maintenance, through hilling, stripping, scratching and the establishment of controlled natural grassing. “These practices are respectful of the earth, the plants and the environment; they support the development of biodiversity and preserve the terroirs. You no longer see the white sand between the vine rows—it is covered by grass and other vegetation. We echo that philosophy in the cellar, being minimalist on the interventions in order to more faithfully reflect the grape varieties and the purity of place.”

Famille Percher, 2019 Cheverny Rouge ($36)

Famille Percher, 2019 Cheverny Rouge ($36)

A 50/50 blend of Pinot Noir and Gamay grown on sandy clay with a limestone base. It is fermented with indigenous yeast and spends 15 days macerating before élevage in stainless steel on fine lees. It shows a frisky nose of black cherries and cassis with an edge of earth—graphite, tree bark, espresso and forest floor. Tannins are moderate and the finish is long.

Fiefs Vendéens: Loire Frontiers, More To Nantais Than Just Muscadet

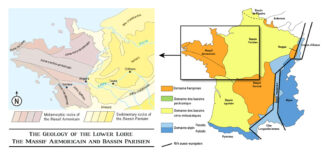

Created in 1984, the Fiefs Vendéens in located in the western end of the Loire Valley, about forty-five miles south of Pays Nantais. Like its neighbors, it boasts a maritime climate and soils that are relatively homogeneous, consisting of red clay derived from schist and limestone and laid over friable bedrock, allowing vine roots to establish themselves and penetrate deeply with ease.

Nevertheless, the appellation is subdivided into five individual zones (the ‘fiefs’ in the name)—Brem, Mareuil, Chantonnay, Pissotte and Vix. Each operates under its own set of rules with its own roster of allowable grapes. The generic AOP covers red, white and rosé wines. While the whites are predominantly made from Chenin and Chardonnay, the reds draw from a pool of five grapes: Pinot Noir, Gamay, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon and Négrette. Depending on the subzone, these are broken into the main grape (at least 40 percent of any blend), complementary grapes (at least ten percent of a blend), and accessory grapes. The rosé is dominated by Gamay and Pinot Noir, and covers about half of the appellation’s production.

Domaine Saint Nicolas (Brem Pinot Noir)

If you were jolly old St. Nick, would you hang around the North Pole during the off-season, or relax in a namesake wine estate in Fiefs Vendéens? If it is the latter, you’ll encounter Thierry Michon—a local legend for his commitment to biodynamics, which is not merely a passion pragmatic consideration.

“For me,” he says, “it is closer to a religion.”

For example, he has purchased buffer acres all around his vineyard to prevent accidental cross contamination and he proudly states that not a single vine on his estate has ever seen a non-organic product. His hundred acre estate is at the extreme southern end of the Loire Delta, just south of Muscadet. But Melon de Bourgogne is not the name of the game here; instead, Thierry works old-vine Chenin, Chardonnay, Grolleau Gris, Gamay, Pinot Noir, Négrette and Cabernet Franc.

Thierry Michon and Sons Antoine and Mickaël (Fiefs-Vendéens Brem)

“We are very simple,” he laughs. “You might say primitive, working by horse and doing everything by hand—or foot.”

And that’s accurate—the harvest is, of course, by hand, but after the whites pass through a sorting table and are then gently pressed and fermented in large wooden vats, the reds are sorted and then crushed by foot. Thierry was recently joined at the winery by his two sons, Antoine and Mickaël, who may no longer believe in Santa Claus, but who definitely believe in Saint Nicolas.

Domaine Saint Nicolas ‘Cuvée Jacques’, 2018 Fiefs-Vendéens Brem ($29)

Domaine Saint Nicolas ‘Cuvée Jacques’, 2018 Fiefs-Vendéens Brem ($29)

100% Pinot Noir between 15 and 25 years old from a gentle hillside facing south-west; schist, clay and quartz soils are enriched using the biodynamic ‘Bordeaux’ mixture, which includes treatments with herbal teas made of nettle and horsetail, etc. The grapes are macerated in wooden vats for 12 days with cap punch-downs. Fermentation is done on native yeast without chaptalization, after which the wine spends a year in oak demi-muids before being bottled unfined and unfiltered, with total sulfites 14 milligrams/liter. The wine is juicy with raspberry and pomegranate, shored up by crunchy minerality and spiced with touches of vanilla, orange rind and cinnamon.

- - -

Posted on 2024.02.02 in Touraine, Anjou, Chinon, Saumur-Champigny, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Loire | Read more...

The Champagne Society February 2024 Selection : Champagne André Heucq + Champagne Solemme

The Rise of Terroir in Champagne

Two New Waves Producers Cultivate The Variety Meunier To Channel Precise Geography in Two Different Sub-regions

Champagne André Heucq ‘Héritage’ Blanc de Meunier, Vallée-de-la-Marne Brut

Nature ($51)

+

Champagne Solemme ‘Terre de Solemme’, Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds Brut ($59)

‘First and foremost, Champagne is wine.’

Our Champagne mantra over the past few years has been a bit reductionist: While undeniably accurate, it’s a little like saying that, first and foremost, ‘David’ is a hunk of marble or that at its essence, La Traviata is a bunch of notes. What these self-evident truths leave out is the human touch—the x-factor that makes art from the inanimate and beauty from the base.

As France warms with the rest of the planet, new regional wines are coming into focus and former sow’s ear soils are producing silk purse products. This is a paean to nature, of course, and as always, the passion arises from the people, not from the place. Folks like Alexandre and Fanny Heucq, fourth generation artisan winemakers from the grower house Champagne André Heucq and Olivier Langlais, the winemaker behind Solemme Champagne, who advocates simplicity and honesty in his wines.

These are two standout icons from our Champagne portfolio, but more than that, they are the flesh behind the finesse.

The Impact Of Climate Change on Champagne: Heating-up

Global wine production in 2023 was at its lowest in 60 years, and a lot of the decline can be blamed on extreme weather events, many of which have been worsened by climate change. Italy dropped from its position as the world’s leading wine maker due to numerous adverse weather events, including erratic rainfall that triggered downy mildew as well as floods, hailstorms and drought. In 2021—for the same reasons—Champagne saw the smallest harvest since 1957.

Somewhere amid all these clouds is a silver lining known as the Goldilocks Zone, and we may be living within it as we speak. Ripening grapes has always been a primary challenge in Champagne, located near the northern growing zone limit of its three principal grapes, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Meunier. Although the rise in temperature (nearly two degrees between 1961 and 2020) has beneficial effects in the short term, especially at higher elevations, the downsides are legion—earlier budburst makes the risk of frost damage more pronounced, and frost control systems, especially those based on combustion, add to the region’s carbon footprint. Not only that, but warmer days often precede warmer nights, affecting a grape’s natural ability to retain acid, giving Champagne its intangible ‘zing’.

Despite magnanimous efforts to reduce their carbon emissions, including use of bio-based products in the fields and cellars, scrapping much of the mineral fertilizers used in the past and planting of hedges and trees allowing a better absorption of CO2 and storage of carbon in soils, the warming of the region is likely to continue for the foreseeable future—potentially, according to ClimateAi, making Chardonnay and Pinot Noir (and to a slightly lesser extent, Meunier) impossible to grow in the area currently defined as Champagne.

That means we may well be in the midst of a ‘best of both worlds’ phenomenon in Champagne, where the positives still outweigh the negatives and we are able to enjoy riper, richer wine that is today (more often than in the past) of vintage quality. By 2050, who knows?

The Biodynamic Principles: Respecting Earth’s Life Forces

Credit Dr. Rudolph Steiner for codifying the basic principles of biodynamics; his 1924 lecture series to farmers opened a wormhole that integrated scientific understanding with a recognition of an underlying spirit in nature and, indeed, in the cosmos at large. In Cliff’s Notes shorthand, the movement recognizes every farm, garden or vineyard as an integrated organism made up of interdependent elements: Plants, animals, soils, compost, and the classically French view of ‘the spirit of a place.’ Biodynamic farmers listen to the land and work to nurture and harmonize these elements, managing them in a holistic and dynamic way. The goal, whether the crop is grain or grapes, is to develop and evolve a given plot of land as a unique individuality.

These principles are custom made to accentuate terroir, but in Champagne, distinctiveness of location has often taken a back seat to a homogenous blend. As a result, the region as a whole was a bit late to the biodynamic party. The era between 1970 and 2000 may be viewed as cringe-worthy in terms of viticulture; the overuse of pesticides and herbicides and the once-favored fertilizer known as ‘boues de ville’—urban waste—damaged soils even in the most prestigious Grand Cru vineyards.

The biodynamic sun came out at turn of the century, when the Comité Champagne conducted in-depth research into the industry’s environmental impact and launched an ambitious plan, resulting in a 20% reduction in carbon emissions per bottle and a 50% reduction in the use of both phytosanitary products and nitrogen fertilizers. A regional sustainability certification, VDC (Viticulture Durable en Champagne), was introduced in 2014 and today, 15% of Champagne’s vineyards falls under the certification, and ambitions are much higher for the future.

Mountains and Valleys: Two Artisans, Two Different Meunier-Centric Champagne Expressions

For the trend conscious (as well as the eco-conscious), Meunier, often the odd-grape-out in discussions of Champagne dominant trio of varietal, is enjoying something of a heyday with a growing legion of fans, both for its frost-resistance and its bright, bergamot-tinted profile. Of the planted acres in Champagne, Meunier represents about 31%, or roughly 84,000 acres. In the Marne Valley, however, it dominates, making up more than 60% of the vineyards.

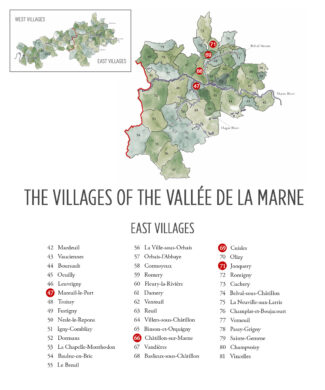

The valley is long—it extends more than sixty miles from the city of Tours-sur-Marne to Château-Thierry, wending thorough two départements, the Marne and the Aisne, all the way to the limits of Seine-et-Marne. As its name indicates, the Marne Valley follows the river through a landscape of rolling hills and small villages. Vines are planted on both banks although those on the north side benefit from a more favorable southern to eastern sun exposure.

The variety of Marne terroirs within its various villages and numerous sub-zones is expansive; in addition, the geology of the soils are more variable in Marne than in other Champagne sub-regions. As a result, the styles of Champagne, even those made mostly or entirely from Meunier, can vary widely. In the Petite Montagne, for example, the Meunier tends to be firmer and more structured, while the wines of the Vallée de la Marne are broader and more ample in build.

Representative of the many faces of Meunier are the artisan producers featured in this week’s package, Alexandre and Fanny Heucq of Champagne André Heucq (whose mineral-focused Meunier is the result of their unique green Illite soils) and Olivier Langlais of Champagne Solemme, a vigneron who stands out from the pack as a true maverick, making Champagnes using only the year’s wines.

The Villages of The Vallée de la Marne: Coldest Weather in Champagne, Clay-Rich Soils

The most famous villages are located at the eastern end of the valley around the city of Épernay, a ranking that reflects the importance given to the presence of chalk in the soil. Chardonnay and Pinot Noir dominate the vineyards of the eastern end of the region, and the major Champagne houses located here include Billecart-Salmon or Philiponnat in Mareuil-sur-Aÿ, Deutz and Bollinger at Aÿ and Jacquesson in Dizy.

West of Châtillon-sur-Marne, chalk tends to be found more deeply buried in the ground; the topsoil is made of calcareous clay and clay marls. The combination of cold weather and rich clay makes Pinot Meunier the grape of choice in this part of the valley and it is here that a new generation of experimental winemakers is deepening their own (and by proxy) our understanding of the varietal.

Fanny & Alexandre Heucq

Champagne André Heucq

In the heart of the Marne valley is the tiny commune of Cuisles (population 150) which happens to be an epicenter for the green illite clay; it is unique to Cuisles and two surrounding villages and it is arguably the terroir where Meunier feels most at home.

According to André Heucq, who—along with his daughter Fanny— specializes in Meunier grown on fifteen acres of estate vineyards, “Green clay retains water better than chalky soils, this type of soil needs less water than classic clay-limestone soils. Generally speaking, the Marne Valley is prone to downpours of rain, and this is where Cuisles’ unique position in the hollow of the valley plays a fundamental role: Showers are much less frequent, so soil and climate are in perfect alchemy for optimum ripening of the Meunier.”

André & Fanny Heucq, Champagne André Heucq

Fanny says that the terroir, so vital to their wines’ purity and elegance, is enhanced by a commitment to biodynamics: “Production that respects the environment reactivates the vine’s natural self-defense mechanisms, allowing us to do away with the use of chemicals and use very low doses of copper and sulfur.

Among the strictest (and most interesting) of the cosmos-oriented techniques the estate relies on is the ‘500’—a preparation is obtained by fermenting good quality cow manure in the soil over the winter, introduced via cow horns. Fanny explains, “This preparation is aimed at the soil and plant roots. Its name comes from the fact that it contains over 500 million bacteria per gram. The silica from the horn is equally important. It is complementary to and acts in polarity with the 500. It is not aimed at the soil, but at the aerial part of plants during their vegetative period. It can be said to be a kind of “light spray”, which can promote vegetative vigor or, on the contrary, attenuate excessive luxuriance. It brings a luminous (crystalline) quality to plants, and reduces their tendency to disease. Not only does it reinforce the effects of sunlight, it also enables a better relationship with the cosmic periphery, with the entire cosmos. This preparation is essential for the internal structuring and development of plants. It promotes vertical plant growth. It makes plants firmer and more supple. It increases the quality and resistance of leaf and fruit epidermis.”

Views From The Right Bank: Meunier Reigns Supreme

Not only an underdog but occasionally an afterthought, growers in Champagne have often planted Meunier vines in areas that will not support the appellation’s noble couple, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Older vines are often found in otherwise marginalized areas, and the grape is not permitted to wear the designation ‘Grand Cru’ even if it is grown exclusively in a Grand Cru village. As a logical result of this elitism, very little Meunier is grown in Grand Cru vineyards and many producers avoid using it in their vintage wines due to its rumored inability to age—a rumor which, incidentally, is unfounded.

As in Bordeaux, the difference between the right and left banks of the region’s dominant river are striking, both in terms of vineyard exposure and soil composition. The Marne is an eastern tributary of the Seine in an area east and southeast of Paris. In Champagne, where it runs west toward Epernay, the right bank sports the valued south/southeast exposure that maximizes sun exposure and aids grape ripening. As with the Right Bank of the Dordogne River in Bordeaux, the Marne’s right bank contains more clay, making it more suited to Meunier than either Chardonnay or Pinot Noir, which may struggle to ripen in the area’s cool, frost-and-fog-prone microclimate.

Champagne André Heucq ‘Héritage’ Blanc de Meunier, Vallée-de-la-Marne Brut Nature ($59)

Champagne André Heucq ‘Héritage’ Blanc de Meunier, Vallée-de-la-Marne Brut Nature ($59)

TCS-1 ($51)

A blend of 100% Meunier harvested in 2016/2017 from 30-year-old vines grown in illite-rich plots in Cuisles, Chatillon sur Marne, Serzy and Mareuil le Port. The wine underwent full malo and spent 48 months on lees; it was dosed to Brut Nature. The nose is nicely spiced with stewed apple and pear with notes of jasmine. A slight lemony bitterness on the finish is a mirror of the terroir. 25,000 bottles made.

Champagne André Heucq ‘Hommage Parcellaire’, 2015 Vallée-de-la-Marne – Jonquery ‘Les Roches’ Brut Nature ($117)

Champagne André Heucq ‘Hommage Parcellaire’, 2015 Vallée-de-la-Marne – Jonquery ‘Les Roches’ Brut Nature ($117)

100% Meunier from younger vines—22 years old—grown in illite in the ‘les Roches’ lieu-dit in Jonquery. The wine is from the 2015 harvest, fermented ‘en barrique’ and aged three years on lees after undergoing full malo. Dosed to Brut Nature. The wine’s bouquet is of peach and plum with notes of pie crust and almond. The long and pronounced minerality in the finish is indeed an earthy homage to the parcel from which it arises. Only 800 bottles were made.

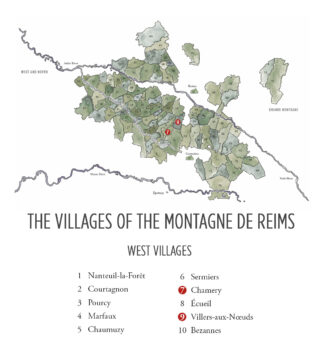

The Montagne de Reims: Grande, Petite, North And The Grand Vallée

Located between Reims and Épernay, the Montagne de Reims is a relatively low-lying (under a thousand feet in elevation) plateau, mostly draped in thick forest. Vines find a suitable home on the flanks, forming a horseshoe that opens to the west.

So varied are the soils, topography and microclimates here that it is not possible to speak of the region in any unified sense. Grande Montagne de Reims, which contains all of the region’s Grand Cru vineyards, covers the northern, eastern and southern slopes of the viticultural area, and Pinot Noir plantings dominate at 57%, followed by Chardonnay (30%) and Meunier (13%). Its vineyards face a multitude of directions, and soil type varies by village, giving rise to a breadth of Pinot Noir expressions, as well as exceptional Chardonnay.

To the west, the Grande Montagne de Reims gives way to the Petite, whose bedrock is chalk, but softer than the chalk found further south on the Côte des Blancs. This sort, called ‘tuffeau’, is an extremely porous, sand-rich, calcium carbonate rock similar to what is found in wine regions of the middle Loire Valley.

In French, the word ‘petite’ often to refers to a ‘lesser’ commodity, but with La Petite Montagne, the reference is to elevation. This lower elevation means warmer weather, even in Champagne’s northerly climate, and in certain villages, the soil contains more sand, making it an ideal environment for growing Petit Meunier.

Meunier accounts for approximately half of the plantings in the Petite Montagne, with Pinot Noir making up 35% and the rest Chardonnay. It is a growing conviction among growers of the modern era that Meunier is a Champagne grape whose time has come, especially as an age-worthy variety.

Emmanuel Brochet of Villers-aux-Noeuds says, “People claim that Meunier ages too quickly, even faster than Chardonnay. I disagree. The curve of evolution is different. Meunier is quick to open and more approachable in youth, but then it becomes quite stable. Chardonnay tends to open later, but old Meunier remains very fresh and lively.”

Olivier Langlais

Champagne Solemme

The name Solemme is a combination of ‘sol’ for the sun, with the addition of a feminine suffix. “My goal,” says cellar master Olivier Langlais, “is to make delicate Champagnes that are bright like the sun.”

La Petite Montagne-de-Reims, to the west of the road between Reims and Épernay, boasts steep slopes and chalky soils, making it the home of some of the best Premier Cru vineyards in Champagne—Savart, Brochet, Egly-Ouriet, etc. Also calling the region home is Olivier Langlais, who farms fifteen acres of organic vineyards in the terroir around Villers-Aux-Noeuds. A true exception in Champagne region, he makes wines using only the product of the harvest year.

His dedication to biodynamics and agriculture according to the cycles of the moon began with the Chardonnay plot in 2009 and finished the transition with his oldest vines of Pinot Noir in 2015. The vineyard is composed of 50% Pinot Meunier, 25% Chardonnay and 25% Pinot Noir divided between six villages—five of them Premier Cru. Most of the plots, as is the case of most Petit Montagne de Reims vines, are southeast/east oriented.

Olivier Langlais, Champagne Solemme

“Everything is happening in the exchange between the soil and the grape”, Olivier points out. “That’s why the difference of terroir between all parcels determines variety and process. Villers-aux-Noeuds has a classic chalky soil, bringing a lot of minerality to the Chardonnay and Meunier growing there. Clay-limestone dominates Chamery and Vrigny, with a bit more clay in Vrigny, where Meunier gets better results—clay gives more ‘gras’, or roundness to the grapes. Often not mentioned is the sandy soils of Villedomange and Eceuil, which gives Pinot Noir a concentrated and elegant form.”

Once in the cellar, Olivier is a champion of a hands-off approach. He never chaptalizes and uses only natural yeast from his vineyard. “In the chai, you won’t find any barrels,” he says. “We do not filter, there is no addition of SO2 and all the cuvées spend between 36 to 48 months on the lees as a means of better expressing the terroir. 90% of the time, I don’t do any malolactic fermentation, because I prefer to let the natural minerality shine.”

Transformation in The Petite Montagne: Meunier Shares Space With Pinot Noir

The western portion of the Montagne de Reim—the so-called Petite Montagne—stretches from Gueux in the north to Sermiers in the south, on the western side of the main road that runs between Epernay and Reims. Although this region has a historical fondness for Meunier, some acres have been replanted to Pinot Noir in recent years, potentially doing a disservice to the vineyards north of Écueil in the villages of as Sacy, Villedomange, Jouy-lès-Reims, Coulommes-la-Montagne, Vrigny and Gueux. But the soils here are generally more overtly calcareous than those in the Vallée de la Marne and can contain a high proportion of fossils. In Écueil, there is sand on the lower slopes, acting as a defense against phylloxera, allowing some growers to plant Pinot Noir on the original rootstocks, so this becomes the cultivar of choice.

Champagne Solemme ‘Terre de Solemme’, Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds Brut (68)

Champagne Solemme ‘Terre de Solemme’, Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds Brut (68)

TCS-2 ($59)

Villers-aux-Nœuds is a Premier Cru village in Vesle et Ardre; about half the vineyards are planted to Pinot Noir, with Meunier making up about 30%, and the rest, Chardonnay. Olivier Langlais farms fifteen acres here; the land is relentless hilly and the soil is made up of Cretaceous chalk under a few inches of ‘argilo-calcaire’ topsoil. Disgorged according to the moon cycle (a feature of his brand of biodynamics), ‘Terre Solemme’ is a blend of 55% Meunier, 25% Pinot Noir, and 20% Chardonnay aged three years on the lees. Buttery toast on the nose along with cooked apple and cantaloupe. The palate has an echo of the nose and a nice marzipan richness that drives the mineral finish home.

Champagne Solemme ‘Ambre de Solemme’, 2016 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds ‘La Motelle’ Blanc de Noirs Brut Nature ($99)

Champagne Solemme ‘Ambre de Solemme’, 2016 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds ‘La Motelle’ Blanc de Noirs Brut Nature ($99)

100% Meunier from the ‘La Motelle’ lieu-dit, filled with 50-year-old Massal-selected vines; these grapes were harvested somewhat late and developed a spectacular ripeness. ‘Ambre’ refers to the color, whose slight tint is the result of skin-contact. The nose sets out with fresh apple and a touch of grapefruit and strawberry coming out, with bold acidity reflected in a spine of salinity that balances an otherwise rich and creamy wine.

Champagne Solemme ‘Esprit de Solemme’, 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Brut Nature ($79)

Champagne Solemme ‘Esprit de Solemme’, 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Brut Nature ($79)

2018 was an excellent vintage in Champagne; the crop was large and healthy, rich in sugar and flavor depth, with all three major grape varieties performing well. ‘Esprit de Solemme’, 2018, is equal parts Pinot Meunier and Chardonnay drawn from chalky soil in Villers-aux-Nœuds and the clay-limestone hillsides of Chamery. This cuvée shows a lovely bouquet: cream, biscuits, pineapple and toasted nuts. The palate is very dry but stays in balance with cream and salinity through the finish.

Notebook ….

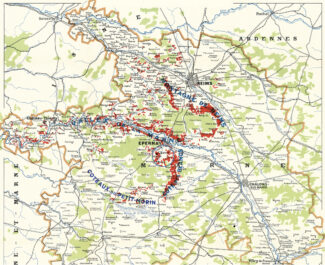

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

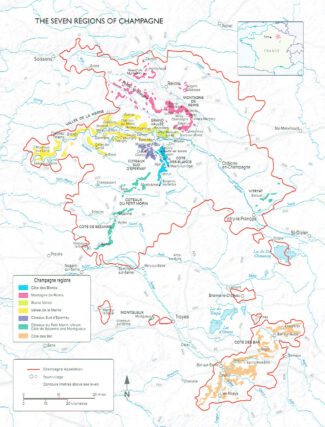

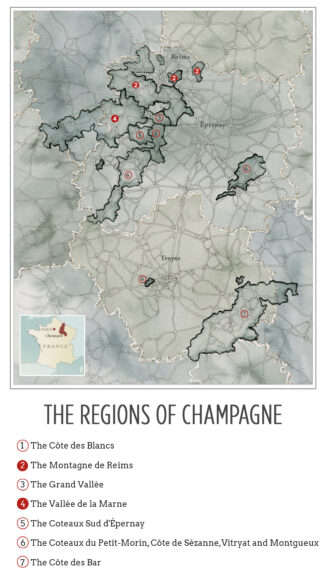

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.