Lure Of The Loire II: A Wide Range Of Red Varieties, Soils And Microclimates Allow For A Diversity Of Wines And Styles By Upstart Generation

The media engine behind French wine seems driven primarily by two wheels—Burgundy and Bordeaux—while the Loire is often relegated to third-wheel status. And it’s not from want of praise: The vivid, crisp, hauntingly aromatic and almost supernaturally focused wines of the Loire Valley are arguably the pinnacle of each particular varietal.

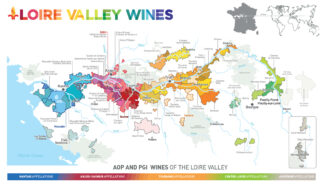

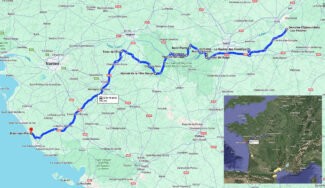

And there are many. 24 varieties flourish throughout the Valley (including indigenous, newly-revived grapes such as Pineau d’Aunis) alongside the Big Four, Melon de Bourgogne, Sauvignon Blanc, Chenin, and Cabernet Franc. The Loire Valley is the biggest producer of white wine in France and the second biggest producer of sparkling wines; it encompasses four sub-regions with more than 51 appellations surrounding the Loire River and its tributaries, flowing from the east around Sancerre to the west toward Muscadet on the Atlantic coast at the mouth of the river.

The Loire is also a hot-bed for experimental winemakers, some of whom have chosen to forgo the hidebound restrictions of the French wine bureaucracy and produce wines on their own terms, opting to use the all-encompassing Vin de France appellation on their labels rather than the prestigious AOPs they’d otherwise be entitled to. Lovers of natural wine know that the Loire was an early pioneer in the movement, and that such producers make wine with organic and/or biodynamic fruit, native yeasts, and a commitment to low-intervention viniculture as a bid for sustainability in the face of changing environment.

These upstart young winemakers have not only been flying under the mainstream radar, they have created their own generation of satellites—fans that recognize wine as an agricultural product as well as a cultural phenomenon, and are drawn to their dedication to natural farming.

This week’s wine selection looks upward toward the light that vignerons in three specific Loire appellations—Anjou-Saumur, Touraine and Fiefs Vendéens—are shining on technique, innovation and originality.

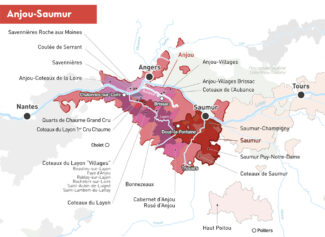

Anjou-Saumur: Driving a Full-on Revolution

In France, where plenty of revolutionaries wound up with their heads in a guillotine basket, ‘revolution’ is not a word to be used lightly. Still, Richard Leroy of Domaine Sophie et Richard Leroy in Bellevigne-en-Layon, Anjou, uses it easily: “There’s a revolution happening in wine right now,” he says, referring to Anjou, once an epicenter for sweet wines like Coteaux-du-Layon and Quarts-de-Chaume.

Over the past twenty years, Anjou has become a hub for a different kind of wine—those made with a minimum of artifice in the cellar, free from historical baggage about what they should taste like and often produced by first-generation winemakers with no family ties to wine.

Another phase of the revolution is the revival of Chenin, which fell out of favor during the second half of the last century as did the native red wine grape, Grolleau. Mark Angeli of La Ferme de la Sansonnière, who arrived in 1989, claims, “Dry Chenin had been gone from Anjou for 50 years, and the few reds being made were mostly rot-gut. Appellation rules required them to be made from the two Cabernets—Franc and Sauvignon—even though old-vine parcels of Grolleau and Pineau d’Aunis thrived throughout the area.”

The region has been attracting maverick winemakers who recognize the scant precedent for complex, dry wines made from Chenin and Grolleau, and who have been happy to bottle their rule-busting wines, farmed organically, under the relatively lowly ‘Anjou’ appellation or even labeled simply as ‘Vin de France.’

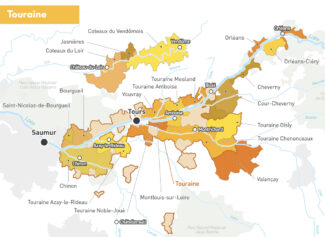

Touraine: The Original Breeding Ground of Pioneering Winemakers And Natural Wines

Most people are more familiar with the Loire’s bookends, Muscadet and Sancerre. But between them lie 79 AOPs representing what InterLoire (the official organization of producers, merchants and traders involved in the production and promotion of Loire wines) calls, “The most extensive, diversified and original vineyards in Europe.”

The AOP covering Touraine stretches from Anjou to the west to the Sologne in the east, converging near the point where the Loire River and its tributaries meet. It covers 104 communes in Indre-et-Loire and 42 in Loir-et-Cher.

Most of the vineyards are located southeast of Tours on the slopes that dominate the Cher River and the land between the Cher and the Loire. With nearly 13,000 acres under vine, the climate varies dramatically as you move inland; oceanic conditions dominate the west, becoming more continental as you move east. These climatic differences combined with varied soils determine the choice of grape variety planted (with later-ripening varieties grown in the west and earlier-ripening ones in the east) and account for the wide variety of wine styles produced.

Among these styles are the personal statement wines of natural winemakers, who have found in Touraine a vibrant opportunity for self-expression as well as terroir that, through minimal intervention, display their origins perhaps even more faithfully than their rule-bound AOP counterparts.

Cabernet Franc

Who’s your daddy? Biologically, both Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot share Cabernet Franc as a parent, and the grape itself displays characteristics inherited by both. In cooler climates, Cabernet Franc shows off graphite and red licorice notes, while in warm regions, it exhibits tobacco and leather aromas. There is also a vegetal edge, which may strike the palate as tasting of green pepper or jalapeño.

In Bordeaux, it is generally a minor component of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot blends, although in Pomerol and Saint-Émilion it adopts a larger, more highly-regarded role. Château Cheval Blanc, for example, is typically around two-thirds Cabernet Franc while Ausone is an even split between Cabernet Franc and Merlot.

With the Loire Valley’s cool, inland climates it becomes a star performer. The appellations of Chinon (in Touraine) along with Saumur and Saumur-Champigny (in Anjou) are important bastions of Cabernet Franc, where the wine is prized for forward aromas of ripe summer berries and sweet spices.

The local Loire Valley name for Cabernet Franc is Breton; a reference to the man credited with bringing the variety to popularity in the 17th Century.

Yannick Amirault (Touraine)

‘Fifty and out’ could be the mission statement of Domaine Y. Amirault, at least in terms of size. With around 30 acres in Bourgueil and 20 in Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil, Yannick Amirault has grown his vineyard space as large as he cares to, finding 50 acres to be the most he feels he can work to his exacting standards.

Having begun in 1977 with around ten acres inherited from his grandfather, Eugène Amirault, he was joined by his son Benoît in 2003. Yannick’s commitment to organic agriculture is not an attempt to hop on the bandwagon sweeping across French viticulture, but rather the opposite: “Weaning the vineyards off synthetic inputs—a process we completed in 1997—and following lunar calendar—may seem a bit trendy, but this is simply a return to the way Eugène Amirault made wine for his family.”

Yannick And Benoît Amirault, Yannick Amirault (Bourgueil, Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil) – (Photo © Jerome Paressant)

Benoît adds: “Harvest has always been done by hand and is initiated by many factors, all guided by combined experience. Each parcel is picked at its own optimal ripeness (and in several passes), then the grape clusters are transported to the cellar. Here, the work is both minimalistic and transparent: Grapes are sorted again and destemmed; fermentations are indigenous and conducted in large, open-topped, conical oak vats; macerations last up to sixty days with pigéage only at the very beginning and rémontage reserved only for the ripest vintages to reduce rustic tannins. Only the first press is used and is aged in neutral vessels—amphorae, oak demi-muids and well-seasoned vats.”

The result of this is a vibrant array of 100% Cabernet Franc wines, many reflecting individual plots across the two appellation; the domain has 25, some above the village on sands and gravels, others at the hill’s feet, in limestone.

“There is no terroir without the intervention of mankind,” says Yannick. “We look after our vines, year after year, as if it were a garden. We grow grass between vine rows and we plough the graveled plots which are more sensitive to a lack of water. Despite weather, our craft leaves nothing to chance. The pruning is Guyot-Poussard and vines through organic spraying of plants infusion. We also roll growing vines (we do not cut the top branches) on certain crus. Even in a low yield year, we do a growth clearing on all our vines in order to ensure an homogenous maturity of the grapes.”

Yannick Amirault ‘Le Grand Clos’, 2020 Bourgueil ($36)

Yannick Amirault ‘Le Grand Clos’, 2020 Bourgueil ($36)

Amirault owns five acres of the lauded, south-facing hillside Le Grand Clos lieu-dit, which is composed of clay and flint soils over tuffeau bedrock. Certified organic, his vines are 45 years old. The grapes are hand-harvested in successive passes, destemmed and allowed natural yeast fermentation in oak vats, and after four weeks of maceration, the wine is transferred to 400 liter French oak barrels for a minimum of one year. The wine is an earthy, black-fruit driven Cabernet Franc that shows the pencil-shavings graphite that are typical of the appellation, one of the few in Loire appellations to produce exclusively red wines.

Yannick Amirault ‘Les Malgagnes’, 2020 Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil ($42)

Yannick Amirault ‘Les Malgagnes’, 2020 Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil ($42)

Les Malgagnes is a hillside lieu-dit in the Bourgueil sub-appellation of Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil. It is slightly further down the limestone-rich slope than the other three lieux-dits on this particular côte. Amirault has six acres here, but only the fruit from the upper section, where the limestone is much closer to the surface, is used for this cuvée. The grapes see a four-week maceration with an élevage lasting 12 months in large barrels and demonstrate the silky elegance of old-vine Cabernet Franc grown in this pretty AOP; rich cassis notes are woven into fine-grained tannins and bittersweet chocolate on the finish.

Pierre Borel (Touraine)

The six-acre Clos du Pavée, where Pierre Borel has been making wine since 2006, is a true clos in the French sense, meaning that it a walled vineyard, once done to protect the grapes from theft and now, to improve the mesoclimate. Pavée soils are gravel; the surrounding acres are generally built around clay/limestone.

“Terror dictates wine style,” Pierre explains, “and this terroir I believe is meant to produce more easygoing, fruit-forward wines.”

This concept ultimately led Pierre to uproot and replant the whole parcel, settling on four new acres of Cabernet Franc and two of Chenin. Doing all the vineyard work alone (and by hand) Pierre is a firm believer in organic viticulture, and although he doesn’t believe that the AOP system is necessarily a mark of quality, he views working within it a commitment to the winemaking traditions in the area.

Pierre Borel (Bourgueil)

The seclusion of Clos du Pavée works to the advantage of Pierre’s passion for organics. With the village on one side and woodland on the other, his acres are under very little threat from contamination from neighboring growers who aren’t playing by his rules. He believes that his wines represent the purity and typicity of wines from Bourgueil—and that is his goal.

“Simplicity is key,” he states. “I make only one wine, and vinify in as straightforward a way as possible. I work with sandy limestone/gravel soils that yields plush, herbaceous and fragrant fruit. I ferment in a simple chai that contains one large tank of stainless steel and one of fiberglass. The wine is racked off the skins after a couple of weeks of maceration and is bottled from tank, with no barrel aging.”

He is also pleased to note that as his new vines mature, they are producing more complex and nuanced wine with each passing vintage.

Pierre Borel ‘Clos de Pavée’, 2019 Bourgueil ‘natural’ ($33)

Pierre Borel ‘Clos de Pavée’, 2019 Bourgueil ‘natural’ ($33)

Bourgueil is the heartland of Cabernet Franc in the Touraine district, and Borel’s five gravelly acres in Clos de Pavée are the epicenter of Bourgueil. This savory, natural red is replete with the meatiness that develops in Cab Franc under ideal condition, and here it is offset by crunchy cranberry and rich herbaceous notes. There is dark chocolate on the finish now, but the wine is structured to mature for at least another decade, and should develop the truffle-like savory tones.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge (Anjou-Saumur)

Intense, driven and passionate, Guillaume Reynouard is the fox in charge of the chicken coop—as well as being a winemaker, he is president of the Syndicat des Vins Saumur and has a particular enmity for growers who rip out Pineau d’Aunis in favor of easier-to-grow varieties.

Taking charge of Domaine Manoir de la Tête Rouge in 1995, Guillaume soon converted to organics and was certified Biodynamic in 2010. The estate enjoys remarkably productive clay/ limestone terroir and he takes pride in ‘living vineyards’ where the soil is worked by hand to ensure that roots go deep and grass grows between rows to promote insect and other plant life; synthetic chemicals are prohibited. In the cellar, grapes are fully destemmed, indigenous yeasts are preferred, with no additions and very minimal sulfur use.

Guillaume Reynouard, Manoir de la Tête Rouge (Saumur, Saumur-Champigny)

According to Reynouard, “Responsible agriculture is a way of life and of thinking. When growing grapes, I aspire to act sensibly for the planet—a state of mind that develops naturally from a respectful relationship with nature. Knowing how to adapt to a changing environment requires constant questioning while the planting of forgotten varieties such as Pineau d’Aunis, the incorporation of trees into the cultivation of the vine (agroforestry) and the gradual abandonment of ‘modern’ oenology are avenues that I have followed for more than 20 years.”

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘l’Enchentoir’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ‘natural’ ($43)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘l’Enchentoir’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ‘natural’ ($43)

In the sub-appellation Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame, ‘l’Enchentoir’ is a venerable Cabernet Franc lieu-dit. Planted over Turonian limestone in 1959 using sélections massales, the pressed wine is aged in 300-liter barriques for one year plus another six months in Béton cuves (pre-cast concrete tanks). It displays depth and delicacy, showing blackberry and cherry over violets, rose petals and savory herbs.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Tête de Lard’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ($27)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Tête de Lard’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ($27)

100% Cabernet Franc from two parcels averaging 20 years of age, ‘Tête de Lard’—Head of Bacon’—is fermented on native yeasts and spends a year in used 300-liter barrels. The final blend is done in concrete tanks, where the wine rests for 4 months before bottling. Filled with ripe tones of blueberry and cassis with a slight vegetal edge, this is a natural wine suited for the cellar, but one that should be tasted every couple years to keep an eye on the progress.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Bagatelle’, 2020 Saumur Rouge ($21)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Bagatelle’, 2020 Saumur Rouge ($21)

A bagatelle is something easy; something that requires little effort. This is not a comment on the precision that is de rigeur in Guillaume Reynouard’s winemaking, especially since the tech sheet for this wine specifies the terroir as 30% Jurassic limestone, 60% Turonian limestone and 10% silt, and the vines as being pruned in alternating Guyot-Poussard. Rather, the wine itself is created simply and naturally, macerated three weeks without yeasting, without chaptalization and without additives, then matured without sulfur. These minuses equal an ultimate plus; a pure Cabernet Franc with aromas of plum, raspberry, and cherry with notes of red pepper, spice, and graphite with silky tannins and bright acidity.

Terre de l’Élu (Anjou)

For Charlotte and Thomas Carsin, winemaking is many things—an interest, then a passion, then a commitment, then a profession. But first and foremost, it’s an adventure.

“My path to Clos de l’Élu began as a grape picker in Burgundy,” Thomas shares. “I was studying tropical agronomy, but ultimately chose to specialize in wine and found work placements in Sonoma, where I learned a great deal about terroir and vinification.”

After that, he learned the retail side of the business in a Paris boutique and spent five years doing consultancy work in Champagne. By the time his stint as a journeyman was over, he had arrived at a very keen personal opinion of the ‘overengineered’ wine industry: He hated it.

Thomas and Charlotte Carsin, Terre de l’Élu (Anjou)

By then he was well-versed in ‘winegrowing empiricism’—the language of the vines and master the idea of terroir. He spent a few more years making wine in Provence, in the département du Var, but it wasn’t until 2008 that he was able to acquire a domain and produce wine on his own terms: “Acquiring Clos de l’Élu, in the heart of the Layon valley, was a dream come true.”

Charlotte’s road to the winery was a bit more straightforward. Having worked in communication with specialized interest in pairing food and wine, she has learned the technical angles hands-on. Of course, her professional chops allow her to serve as the wineries administrator, in the sales and marketing of the winery, and especially brand image, packaging, events, and communication methods.

As to the estate, Terre de l’Élu is in Saint Aubin de Luigné; the vines grow on the outskirts of the village between Chaume and Ardenay, on the right, south-facing side of the Layon River. Soils here are classic Anjou Noir, full of volcanic rocks, sandstone and quartz.

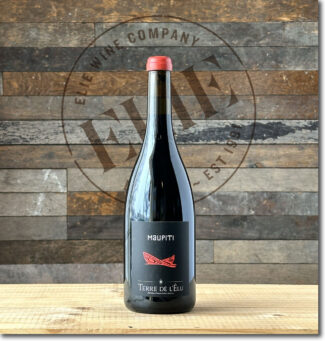

Terre de l’Élu ‘Maupiti’, 2021 VdF Loire-Anjou Rouge ($26)

Terre de l’Élu ‘Maupiti’, 2021 VdF Loire-Anjou Rouge ($26)

Thomas and Charlotte Carsin may have thrown a dart at a map of French Polynesia and landed on the tiny island of Maupiti to name this wine, which they describe as ‘approaching like a mysterious island amid the languor of oceans; you want to explore.’ A blend of 30% Gamay and 70% Cabernet Franc from vines between 25 and 40 years old, the grapes are whole-cluster-fermented separately on native yeasts and only blended after the completion of malolactic. The wine retains the brightness of Anjou Gamay, showing vivacious raspberry aromatics and the solid savory core of Cabernet Franc.

Le Sot de l’Ange (Touraine)

Although the label’s name roughly translates to ‘Idiot Angel’, winemaker Quentin Bourse is anything but. Before taking over a friend’s estate in time for the 2013 vintage, Bourse worked in various fields (some wine related; others not) including numerous internships in the surrounding area. Having learned technique from both natural and conventional producers, notably a six-month stage at the famed Vouvray producer Domaine Huet, his winemaking philosophy was shaped by philosophy and a relentless work ethic that leans toward innovation and the sort of perfectionism that is often at the root of natural wines—at least the ones that shine.

Unusual for the neighborhood, Bourse’s estate is certified biodynamic. Ranging across 30 acres, he is especially attracted to indigenous varieties that capitalize on the clay and silica soils for which the region is famous. In many of his parcels, white silex stones litter the rows making it look as if the terroir is seeping from the earth.

Quentin Bourse, Le Sot de l’Ange (Touraine)

He shares a cellar with old-school producer Pascal Pibaleau, where his grapes are painstakingly sorted four times before whole-cluster fermentation with indigenous yeasts in tank, and then a slow, gentle pressing that in some cases lasts five or more hours. Aging occurs either entirely in tank, neutral barriques, or amphorae depending on the cuvée, and zero sulfur is added during the winemaking process for the reds; a touch is added for the whites.

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Karadras’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine Cabernet Franc ‘natural’ ($24)

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Karadras’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine Cabernet Franc ‘natural’ ($24)

‘Karadras’ is 88% Cabernet Franc and 12% Côt; the name proves to be somewhat inexplicable since it appears in different spellings on different bottlings. What remains the same is that after being manually destemmed in wicker baskets, the fruit ferments in open wooden tanks and comes out the other end with a classic profile; a bit of color from the Côt, herbaceous notes from the Cab Franc. It offers dusty plum, soil, cocoa, and brambles; the palate is lively and fresh, lifted by crunchy acidity framing the ripe high-toned blue fruits, juicy plum and earthy spices.

Côt

‘Côt by any other name would smell like Malbec.’ With apologies to the Bard, the renaissance of this dark, potent grape in the Loire sees a remarkable change in profile. In southwest France—Cahors in particular—the variety produces heavy wines that are not only amenable to long periods of aging, they virtually demand it. In the Cher Valley, in the heart of Touraine, the grape finds a kinder, gentler environment where it produces a different sort of wine; less aggressively tannic with fresh aromas of black cherry and cassis. In part, it is the climate, but the fiercer aspects Côt as they appear in Cahors’ ‘black wines’ are tempered in the field, where vines are pruned short with a vendange vert after véraison. To avoid the additional tannins of oak, most of the grapes are fermented and aged in stainless steel tanks with a few barriques blended in.

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Le Jardin’, 2018 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘Côt’ ‘natural’ ($45)

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Le Jardin’, 2018 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘Côt’ ‘natural’ ($45)

100% Côt from an interesting lieu-dit with two distinct soil types—one section with clay and silex soils and the second with clay and limestone. The wine is vinified using whole-cluster fermentation in concrete tank; malolactic fermentation and élevage occur in terra cotta amphorae for 24 months. The wine shows aromas of freshly-picked bramble fruits, blackberry and currant, with slight Szechuan pepper notes and a touch of clove; a fresh, gripping palate.

Le Rocher des Violettes (Touraine)

Louis Barruol is known to be a tough taskmaster; he is the legendary Château de St-Cosme winemaker who transformed the family’s Gigondas estate from an anonymous bulk-wine source to the top winery in Gigondas—arguably into one of the best estates in the Southern Rhône. It is here that Xavier Weisskopf, founder of Le Rocher des Violettes (in 2005) went to work after studying winemaking in Chablis and Beaune and earning his degree in viticulture and oenology.

At Château de St-Cosme, Weisskopf rose to the rank of Chef de Cave, making four vintages during his tenure there. But he recognized that Rhône was not the best spot to grow his pet grape, Chenin, and that Montlouis-sur-Loire was. In 2005, he was able to purchase a site of old Chenin vines, many planted before World War II, in Montlouis, as well as Côt vines in Touraine, and he settled in to produce wines that allowed his new terroir to speak with clarity. This involved converting the farming practices to organics and extending the philosophy of ‘tradition’ to the cellars.

Xavier Weisskopf, Le Rocher des Violettes (Touraine, Montlouis-sur-Loire)

“Since 2010, my wife Clémence has been a part of the adventure, excelling in the administrative and commercial side of the business,” he says. “We have an additional team who work according to the season. Among our projects, we have been involved in an attempt to restore old vines to their original condition. We have dug a cellar in our native tuffeau so that the wines may age in the best conditions; it is built on multiple levels so that our mechanical force is provided by gravity. The constant cellar temperature is between 13 ° and 14 °C, allowing for the thermal self-regulation of the Allier oak barrels during fermentation.”

Le Rocher des Violettes ‘Côt’, 2020 Touraine ($23)

Le Rocher des Violettes ‘Côt’, 2020 Touraine ($23)

From seven individual plots, the grapes are 80% whole cluster fermented and aged 14 months in neutral foudres. The Malbec nose is unmistakable—a powerful blend of sweet and sour cherry and country herbs that, given time to open up, reveals coffee, leather, black pepper, vanilla and tobacco.

Pineau d’Aunis

‘Riches to rags’ may well summarize the Pineau d’Aunis story. Once a popular and sought-after variety among royalty on both sides of the English Channel, it is now increasingly rare, and generally limited to rosés and the lighter reds of the central Loire.

Part of the grape’s fall from grace is the fact that it is simply a pain in the neck to grow. Prone to irregular yields, it is also highly susceptible to bunch rot and hyper-sensitive to the soil it is grown in, requiring a balance of clay, sand and gravel in order to produce a crop of much commercial value. It is only in seasons of prolonged heat that it is capable of making red wine as distinctive and interesting as that made from the more ubiquitous Cabernet Franc.

And yet, of late, warmer seasons is exactly what has been happening in the Loire and as the more experimentative winemakers of the region are discovering, the dry reds made from the grape under optimal conditions show how presentable Pineau d’Aunis can be at the table of either kings or pawns.

Terre de l’Élu ‘Espérance’, 2021 VdF Loire-Anjou ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ ($47)

Terre de l’Élu ‘Espérance’, 2021 VdF Loire-Anjou ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ ($47)

100% Pineau d’Aunis from a variety of vine ages (seven years to 60), grown on rocky clay and schist. The grapes are allowed two weeks to macerate whole-cluster in stainless steel; they are then pressed and aged in neutral oak as fermentation completes. The wine is bottled with a minimum of sulfur and no fining. It shows the floral nose and spicy, fleshy body associated with this ancient grape; dried violet opens to raspberry and spiced cherry with a bit of crushed stone toward the finish.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘K’ Sa Tête’, 2020 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ Guillaume Reynouard ($27)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘K’ Sa Tête’, 2020 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ Guillaume Reynouard ($27)

100% Pineau d’Aunis from the lieu-dit de l’Enchentoir where soils are treated using Maria Thun’s biodynamic advice; this includes cow-horn dung in the spring and horn silica after closure of the cluster (a somewhat exacting process that is exactly what is sounds like, using cow-horns filled with manure and/or silica). Maceration lasts 12 days in concrete tanks without yeasting, chaptalization or additives. The wine spends six months in oak barrels and bottling is done in June with 20 milligrams of added sulfur. This is a textbook Pineau d’Aunis with black pepper and green pepper on the nose with a palate that expands to include sweet, perfectly ripe blueberries.

Grolleau

Grolleau is the Loire Valley’s workhorse grape, used most often in the production of rosé. Although it remains one of the Loire’s most planted red-wine varieties, new plantings have dropped steadily for the last 50 years. While Grolleau is high yielding, providing a steady, reliable harvest, it poses several challenges for growers as it is susceptible to disease and not a particularly flavorful stand-alone variety. It is a dark grape on the vine, but thin-skinned, meaning that there is not much chance for color extraction, so it is rarely used to produce red wines.

Grolleau-based wines tend to be high in acid, moderate in alcohol, and may show aromas of strawberry, raspberry and cherry; as a rosé, it is reminiscent of watermelon, tangerine, rose petals and red candy.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘À Tue Tête’, 2021 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Grolleau Gris’ Guillaume Reynouard ‘natural’ ($25)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘À Tue Tête’, 2021 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Grolleau Gris’ Guillaume Reynouard ‘natural’ ($25)

Vin de France is the most basic quality tier for wines from France, typically uncomplicated everyday drinks, likely blends, but occasionally are made from unlisted, unqualified varieties. Loosely translated to ‘loudly’, ‘À Tue Tête’ is a rare bottling from an even more rare variety, Grolleau Gris, which is a pink-skinned mutation of Grolleau. Handled with the biodynamic tool-kit, the wine shows red cherry, sandalwood and a bit of tropical fruit.

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘OG Grolleau’, 2020 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘natural’ ($39)

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘OG Grolleau’, 2020 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘natural’ ($39)

IGP (Indication Géographique Protégée) is a quality category used for French wine positioned between Vin de France and Appellation d’Origine Protégée (AOP). (The category superseded Vin de Pays in 2009.) Most significant in commercial terms is the fact that the wines may be varietals and labeled as such. ‘OG Grolleau’ comes from single parcel of old-vine Grolleau planted between 1945 and 1976; grapes are de-stemmed, given ten days of maceration, aged in amphorae and used oak barrels, then bottled without sulfur. Blueberry and violet dominate the nose while the palate resolves itself in a mineral crunchiness with beautiful acidity.

Domaine Marie Thibault (Touraine)

“I grew up in the Loire Valley, but unlike many vignerons working in the Loire, I did not come from a winemaking family,” says Marie Thibault, adding, “But also unlike many of them, I have degrees in both biology and oenology.”

Marie Thibault began making wine in the early 2000s, working for a time with François Chidaine in Montlouis, where she fell in love with Chenin. In 2011, she founded her own nine-acre estate on a single windy slope in Azay-le-Rideau, a lesser known commune of Touraine. She immediately converted to organics and has been certified with Ecocert since 2014. Among the natural elements in her vineyards is the flock of two dozen ewes that graze between the vine rows during the autumn; every ten days, they are penned inside a new hectare to keep the soil naturally fertile and the grass clipped.

Marie Thibault, Domaine Marie Thibault (Touraine) – (Photo © Jean-Yves Bardin)

“My vineyard is small, but the soils are extremely varied and as such, so are the grapes I grow. I work with Côt (Malbec), and have a special love for Gamay, Grolleau, Chenin and Sauvignon Blanc. Most of my vines are at least 50 years old. I compensate for small production by purchasing from organic estates nearby.”

Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Le Grolleau’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘natural’ ($89) 1.5 Liter

Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Le Grolleau’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine Rouge ‘natural’ ($89) 1.5 Liter

A wine whose heritage is perfectly reflected in Thibault’s scant acres—Azay-le-Rideau is ground zero for Grolleau, first planted in early 19th century. ‘Le Grolleau’ is an ultra-fresh example made using Beaujolais-style carbonic maceration and held to a little over 11% abv, which solidly qualifies it as a ‘vin de soif.’ It is made using 60-year-old organic vines planted on hillsides on the southern slopes of the Indre—an early-ripening terroir filled with draining soils with a presence of flint, and bottled at the Estate in April 2022 without fining or filtration and just a micro-dose of sulfur. This wine is kept even fresher en magnum; it is fruity, juicy and velvety with sweet cranberry, blueberry, red plum, blueberry, cranberry, a touch of pepper with black cherry on the finish.

Gamay

Ever since Philippe de Bourgogne cast Gamay from the bosom of Burgundy six centuries ago, the variety has been derided and even despised outside its spiritual home, Beaujolais. Folks who were soured by the sweet and fruity Nouveau cult may bring that prejudice into Touraine, but that would be a mistake: Although once in the shadow of Anjou Gamay, select vignerons in Touraine have made monster strides with Gamay over the past couple decades and these wines now edge out the Gamays of Anjou in depth and complexity. They tend to be medium-bodied with a musky tone that share center stage with aromas of fern and capers intermingled with flinty minerals and plummy notes.

Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Les Grandes Vignes’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘Gamay’ ‘natural’ ($41)

Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Les Grandes Vignes’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘Gamay’ ‘natural’ ($41)

Thibault’s unique lens on Gamay is seen in this example produced from 50+ year-old vines she discovered growing adjacent to her plot on flinty silex soil. The vines were untrained and un-trellised, and harvest was exceptionally labor-intensive. She allows a 10-month maceration in order to shows off the Gamay’s savory side, with crisp rhubarb, earthy red berry notes and fine-grained, well-integrated tannins showcased.

Famille Percher (Touraine)

Perhaps the most interesting parcel farmed by Luc Percher (of Domaine l’Epicourchois) is ‘La Marigonnerie’ directly adjacent to the winery. In Napoleon times the vineyard area was a pond, and although the region sits on a bed of limestone sprinkled with granitic sand, the pond left behind a bed of clay which, about 120 years ago, was planted to Romorantin—a local white wine variety with its own appellation (Cour-Cheverny) where it is the only grape permitted.

Luc began making wine here in 2005. “When I arrived, the sand was as white as a beach. I fell in love with the ambience—a few wispy trees and an expansive horizon-line. It is quiet terroir.”

Luc Percher, Famille Percher (Cheverny, Cour-Cheverny)

His 22 acres of vines, tended with certifications from BIO and Déméter, is hardly restricted to Romorantin, although only his 100% Romorantin can be labeled Cour-Cheverny. His Sélection Massale old-vine vineyards contain ten different grape varieties, and some even more rare than Romorantin—Menu-Pineau, Gamay Fréaux and Chaudenay, for example. In order to maintain the biological heritage of these grapes, Luc is committed to soil maintenance, through hilling, stripping, scratching and the establishment of controlled natural grassing. “These practices are respectful of the earth, the plants and the environment; they support the development of biodiversity and preserve the terroirs. You no longer see the white sand between the vine rows—it is covered by grass and other vegetation. We echo that philosophy in the cellar, being minimalist on the interventions in order to more faithfully reflect the grape varieties and the purity of place.”

Famille Percher, 2019 Cheverny Rouge ($36)

Famille Percher, 2019 Cheverny Rouge ($36)

A 50/50 blend of Pinot Noir and Gamay grown on sandy clay with a limestone base. It is fermented with indigenous yeast and spends 15 days macerating before élevage in stainless steel on fine lees. It shows a frisky nose of black cherries and cassis with an edge of earth—graphite, tree bark, espresso and forest floor. Tannins are moderate and the finish is long.

Fiefs Vendéens: Loire Frontiers, More To Nantais Than Just Muscadet

Created in 1984, the Fiefs Vendéens in located in the western end of the Loire Valley, about forty-five miles south of Pays Nantais. Like its neighbors, it boasts a maritime climate and soils that are relatively homogeneous, consisting of red clay derived from schist and limestone and laid over friable bedrock, allowing vine roots to establish themselves and penetrate deeply with ease.

Nevertheless, the appellation is subdivided into five individual zones (the ‘fiefs’ in the name)—Brem, Mareuil, Chantonnay, Pissotte and Vix. Each operates under its own set of rules with its own roster of allowable grapes. The generic AOP covers red, white and rosé wines. While the whites are predominantly made from Chenin and Chardonnay, the reds draw from a pool of five grapes: Pinot Noir, Gamay, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon and Négrette. Depending on the subzone, these are broken into the main grape (at least 40 percent of any blend), complementary grapes (at least ten percent of a blend), and accessory grapes. The rosé is dominated by Gamay and Pinot Noir, and covers about half of the appellation’s production.

Domaine Saint Nicolas (Brem Pinot Noir)

If you were jolly old St. Nick, would you hang around the North Pole during the off-season, or relax in a namesake wine estate in Fiefs Vendéens? If it is the latter, you’ll encounter Thierry Michon—a local legend for his commitment to biodynamics, which is not merely a passion pragmatic consideration.

“For me,” he says, “it is closer to a religion.”

For example, he has purchased buffer acres all around his vineyard to prevent accidental cross contamination and he proudly states that not a single vine on his estate has ever seen a non-organic product. His hundred acre estate is at the extreme southern end of the Loire Delta, just south of Muscadet. But Melon de Bourgogne is not the name of the game here; instead, Thierry works old-vine Chenin, Chardonnay, Grolleau Gris, Gamay, Pinot Noir, Négrette and Cabernet Franc.

Thierry Michon and Sons Antoine and Mickaël (Fiefs-Vendéens Brem)

“We are very simple,” he laughs. “You might say primitive, working by horse and doing everything by hand—or foot.”

And that’s accurate—the harvest is, of course, by hand, but after the whites pass through a sorting table and are then gently pressed and fermented in large wooden vats, the reds are sorted and then crushed by foot. Thierry was recently joined at the winery by his two sons, Antoine and Mickaël, who may no longer believe in Santa Claus, but who definitely believe in Saint Nicolas.

Domaine Saint Nicolas ‘Cuvée Jacques’, 2018 Fiefs-Vendéens Brem ($29)

Domaine Saint Nicolas ‘Cuvée Jacques’, 2018 Fiefs-Vendéens Brem ($29)

100% Pinot Noir between 15 and 25 years old from a gentle hillside facing south-west; schist, clay and quartz soils are enriched using the biodynamic ‘Bordeaux’ mixture, which includes treatments with herbal teas made of nettle and horsetail, etc. The grapes are macerated in wooden vats for 12 days with cap punch-downs. Fermentation is done on native yeast without chaptalization, after which the wine spends a year in oak demi-muids before being bottled unfined and unfiltered, with total sulfites 14 milligrams/liter. The wine is juicy with raspberry and pomegranate, shored up by crunchy minerality and spiced with touches of vanilla, orange rind and cinnamon.

- - -

Posted on 2024.02.02 in Chinon, Saumur-Champigny, Touraine, Anjou, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Loire

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Aligote, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Cinsault, Clairette, Corvina, Counoise, Dolcetto, Erbamat, Ferrol, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Gamay, Garnacha, Garnacha Tintorera, Gewurztraminer, Graciano, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malbec, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marcelan, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montònega, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscat, Natural, Niellucciu, Parellada, Patrimonio, Pedro Ximénez, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Pouilly Fuisse, Pouilly Loche, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Riesling, Rondinella, Rose, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sagrantino, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Sciacarellu, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Search