The Paradox of Chenin: Three Neo-vignerons Use The Variety To Explore Anjou Noir’s Microclimates And Soil Complexity With Unique Collection Of Grand Crus And Single-plots

Chenin shares some traits with Marilyn Monroe; it’s blonde, beautiful, rather dreamy and frisky… and, of course, it’s easily exploited. Chenin certainly has a tawdry side (the generic jugs—no pun—from Gallo, circa the 1970s), but when allowed to shine—as Monroe did in ‘Gentlemen Prefer Blondes’—it becomes a classic icon; a phenomenon and galaxy unto itself.

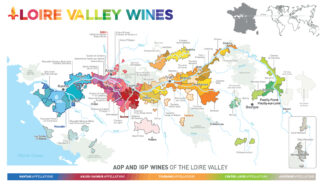

Monroe reinvented herself when needed, going from cheesy pinup fodder to a Time Magazine cover icon in a dozen years. In the Loire, spiritual home to Chenin since the 15th century, a new generation of trailblazers (both neo-vignerons and heirs of historic properties) are introducing a similar evolution in style and substance, extending the range of high-quality, age-worthy dry Chenin into areas where schist, rather than limestone, form the growing medium.

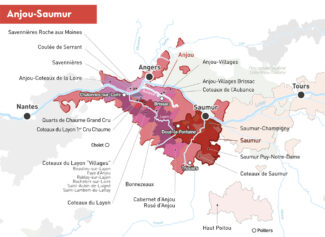

It’s fair to say that Chenin’s reputation in the Loire has been largely built on its ability to produce unique sweet wines—mouthwatering, luscious examples can be found throughout the Middle Loire, particularly in Quarts-de-Chaume and Bonnezeaux (two enclaves within the Coteaux du Layon) and in the twin appellations of Vouvray and Montlouis-sur-Loire. These wines are generally the result of botrytis, to which the region’s climate is susceptible and enhanced by the fact that harvest is often not until November, by which time the grapes have had plenty of hang time to develop natural sugars. This may be further encouraged by allowing the bunches to dry on the vine, and some undergo the process known as ‘passerillage’ wherein they are dried after harvest.

Of course, dry Chenin has always had its niche and its loyalists—nowhere more prominently than in Savennières. Falling within the wider Anjou district, the appellation once had a prominent seat on the sweet wine bandwagon, but in the latter decades of the 20th century producers began specializing in the drier styles for which Savennières is known today, standing proudly as the only dry white appellation in Anjou’s sugary sea.

Some may like it hot, but with a slight chill, there are few white wines that offer more in terms of sensuous oomph and hedonistic delight, and this week, we’ll take a look at some of the upstarts in the region, with a focus on Anjou and Savennières and an overview of the botrytis phenomenon and how it gilds the sugar lily.

The Package: Six Wines For $299

This week’s package offering is comprised of two bottles from each domain for a total of six bottles at $299. The selected wines are numbered and, also, indicated in the write-up about the wine.

Anjou Noir: A Collection of Soils With Chiseled Character

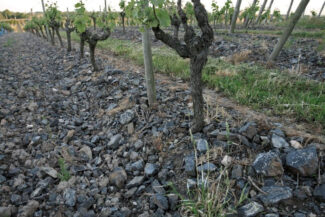

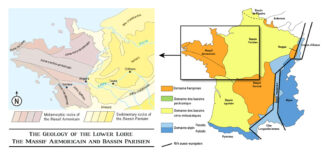

Lest we go overboard with the oxymoron ‘Anjou Noir’, the varietal in question is white, the wine is white (with golden tints) and even the botrytis is sort of white. It’s the soil of the region (in the western part of Anjou, toward Brittany), veined with black charcoal from forests 500 million years old, that earned Anjou Noir its name.

Anjou Noir, a land of Schists (Château d’Epiré, Photo by Philippe Caharel)

Highbrow terroir experts refer to this soil as ‘metamorphic schistous’ and it is among the oldest soil in France—a plus, since the rock base has had plenty of time to degrade and weather into usable minerality. In addition, the slopes of Layon are on a fault-line that appeared during the creation of the Alps and resulted in a multitude of microclimates based on the proximity of rivers and hillsides. The region lays claim to a wide variety of soils—sandy clay on plateaus, slopes of purple and gray schist crossed by veins of volcanic rock, and all flavors in between. Dark schist rocks are a chromatic contrast to the white tuffeau found in eastern Anjou, and nowhere is this displayed more strikingly in the medieval ‘striped’ castles of Angers, Anjou’s capital, which used both for construction.

One vinous advantage of this ancient, undulating landscape is the creation of multiple individual spots with particularly advantageous terroir. Called ‘climats’ in Burgundy and lieux-dits elsewhere, these are the source for the plot-specific wine of which the maverick new wave of vigneron in Anjou are enamored.

The Protean Dry Chenin: Transparent Expression

Chenin can produce some neutral and forgettable wines, and that is self-evident in the Central Valley bulk stuff that California has produced over the years. In such styles, chaptalized sweetness is done for more than customer appeal; it hides various flaws inherent to substandard farming. Of course, there is little excuse for flawed wine using today’s craft and to be sure, the sweet wines of the Loire are examples of the highest art of concentrated grape sugars, capable of aging and improving for decades—in part because sugar also acts as a preservative.

Creating a dry wine that can improve with years in the bottle is a tougher nut to crack, especially if no oak—also a preservative—is not used. This is where Chenin’s other natural propensity comes into play: Acidity. In Burgundy, Chablis—with or without oak—is well known for its longevity, caused in part by the acidity that Chardonnay displays when grown in chalky soil. Chenin puts on the same razor-sharp pageantry when grown in schist, and like Chardonnay, it is a variety that echoes terroir transparently, and as such, too much oak or added sweetness may work against this inherent expression.

Is there a downside? Undoubtedly. With very young Chablis, the steely bite of immature acid may be unpleasant, and many require a few bottle years to mellow toward splendor. Whereas Chenin is filled with lovely and complex flavors young, the ‘brut zero’ versions require about the same length of time to veer toward their peak.

Savennières: Chenin For Thought

Savennières is as small an appellation as its wines are big. It is the the Loire Valley AOP where Sauvignon Blanc yields ground to Chenin—the only variety legally allowed in this tiny (fewer than four hundred acres) appellation.

We likened Savennières Chenin to Chablis Chardonnay above; a correlation can also be drawn with German Riesling. Capable of producing unctuous sweet wines, it also shows a keen, mineral-tinged profile when dry, both capable of years—even decades—of bottle growth given the right vintage and the right cellaring conditions. And it remains a bit of a secret: Even with two remarkable sub-appellations, La Rouche aux Moines and the monopole La Coulée de Serrant facing south along the Loire River, the appellation does not get much glad-handing by trade and consumer press. This may be seen as a marked contrast between the ballyhood Vouvrays from further east in Touraine. That’s generally because even age-worthy Vouvray is easier-going and more accessible when young, grown on soils of clay and tuffeau (a form of limestone) as well as flinty silex. In Savennières, the vineyards are largely built on schist, sandstone and rhyolite (a volcanic rock) and in their youth, Savennières can have the jolting sizzle of austerity.

In part, of course, Savennières’ under-the-radar status is its own doing. Historically, growers have tended to produce wines reductively, harvesting their grapes with a potential alcohol of 12º, picking them when they were still green in color. These practices resulted in rather backward wines which, for the most part, came to define Savennières’ ‘typicity.’ True, with a decade in the bottle, this style of wine can show great depth and elegance, but you have to be a particularly knowledgeable and patient consumer to go through these steps to wind up with an enjoyable wine.

… Which is why the new guard of winemaker has begun to make changes in Savennières, and perhaps most emblematic of this is Domaine Laureau. With bottle age, these are among the most elegant expression of Chenin to find today, oozing with honey, acacia and ripe apples.

Domaine Laureau

Every winemaker in Savennières would probably like to be referred to as ‘… undoubtedly, the future star of the appellation’ by ‘La Revue de Vin de France’ but it only happened to one: Damien Laureau, working out of a small shed in Epiré, nine miles southwest of Angers, and cultivating 15 acres of Chenin in Savennières and Savennières Roche-aux-Moines. Along with his wife Florence, he considers himself an ‘agricultural engineer’ whose promise to the alliance they have formed with nature is to reflect ‘the earth in light.’

Part of this alliance involves using fruit extracts and other non-synthetic treatments on the vines in place of harsh chemicals, and allowing wildlife and indigenous plants to share space with the Chenin. Like a few other area growers, Damien is starting to experiment with harvesting when the grapes turn yellow (instead of the traditional Savennières ‘green grape’ stage) to take advantage of the richness of the sun—the ‘earth in light’. At the same time, he is careful not to pick late in order to avoid the high levels botrytis to which the region is prone. Relying on low yields (an average of 35 hectoliter/hactare is quite common) his wines are emblematic of beautifully balanced dry wines for which Savennières is increasingly known, built around richness, concentration, lively acidity and length.

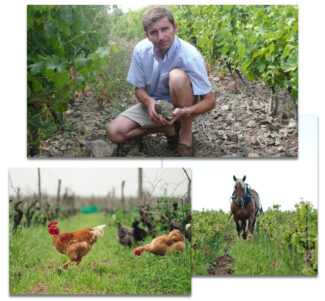

Damien Laureau, Domaine Laureau

“We put our know-how to work for the benefit of terroir,” Damien maintains. “All vineyard treatments and work in the cellar is organic; we have been ECOCERT certified since 2012. We are a microscopic domain compared to many—we have two employees, Patrick and Aurélien, who put all their energy into the daily manual work, delicately and carefully, close to the vine. In the cellar, our wines are aged simply, in barrels, tanks or jars. No filtration is allowed, to keep the wines nicely aromatic and well-structured.”

Florence adds: “The grapes are harvested by successive selections, pressed directly, settled for 12 hours, and put in fermentation (indigenous yeasts) for sometimes a year, in vats or in barrels depending on the terroir. Each micro-terroir is identified and vinified separately. The wines are aged on lees for 18 to 24 months allowing the wine to acquire roundness, complexity and charm. The character of the chenin and the terroir are respected by a gentle, long and non-interventionist breeding.”

•Bottle1•

•Bottle1•

Domaine Laureau ‘L’Alliance’, 2022 Savennières ($32)

The alliance referred to in the wine’s name is between small parcels of younger vines, including the lieux-dits La Petite Roche and Pitrouillet, that Damien himself planted on sandy grey schist between ten and twenty years ago. These vines have been farmed organically from the start, worked by hand, and plowed by horse. Damien Laureau selects the lightest and freshest musts at the time of pressing to create a wine, though able to age, that is ideal for consumption in its youth. The wine spends ten months in tank on the fine lees and is bottled unfined and unfiltered; it shows sweet apple and pear, a touch of Angostura bitters and wormwood behind a minerality that is not as steely as some young Savennières.

•Bottle 2•

•Bottle 2•

Domaine Laureau ‘Les Genêts’, 2020 Savennières ($50)

Genêts, named for the yellow flowering broom plant, is another firm and textured wine that can be enjoyed in its youth. In part, this is because the vineyards clustered around the Moulin de Beaupréau at the far northern edge of the appellation host a light, sandy terroir of schist and phtanite, and produce wines that are high in acidity, but round on the palate. This is further enhanced by a year in large oak casks, then six months in tank before bottling. It shows pronounced Anjou pear on the nose along with magnolia and Macadamia nuts, and an elongated and pure finish where the acid is embracing rather than shocking.

Domaine Laureau ‘Le Bel Ouvrage’, 2020 Savennières ($64)

Domaine Laureau ‘Le Bel Ouvrage’, 2020 Savennières ($64)

Le Bel Ouvrage (‘Nice Piece of Work’) is a wine that reflects a trio of terroirs in La Petite Roche, a vineyard in eastern Savennières near Laureau’s home-base village of Epiré. Soils here are largely grey schist and rhyolite and produce wines that may seem a bit clumsy when young, but evolve to offer sweet and savory notes of peach jelly and butter-rich pastry. The wine shows rich phenolic texture and focused acidity, enhanced in part because, in 2016, Laureau stopped malolactic fermentation in his wines.

Domaine Laureau ‘Champs Bourcier’, 2019 Savennières ($108)

Domaine Laureau ‘Champs Bourcier’, 2019 Savennières ($108)

This is an interesting, weather-driven cuvée born of the 2019 vintage, which so compromised the production of ‘Le Bel Ouvrage’ that Laureau bottled from his father’s old vineyard instead. ‘Bel Ouvrage’ is a cuvée name, not a lieu-dit, but ‘Champ Bourcier’ is a vineyard plot rich in rhyolite—magmatic rock woven through with threads of micro-granite. The wine sees 30 months aging on the lees, including 12 months in 400 liter oak barrels and 18 months in 1200 liter sandstone jars; the profile shows crisp green apple, honeyed pear counterbalanced by a revitalizing undercurrent of acidity.

Anjou: Chenin At Large

As is the case in Burgundy and Bordeaux, the catchment called ‘Anjou’ is a regional appellation that encompasses a very wide region in the Loire, and is subject to a set of regulations far less restrictive than those for the sub-appellations we have singled out here. For one think, it does not even require Chenin whites to be pure Chenin, and many are not; up to 20% Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay is permitted by law.

The Anjou AOP also covers red wine made from Gamay and sparkling wines, although rosé is covered under two separate appellations, ‘Rosé d’Anjou’ and ‘Cabernet d’Anjou.’

Chenin, the focus of our package this week, does exceptionally well in Anjou, in part because of its chameleon-like tendency to step up to the plate in essentially any weather pattern and alter its profile to suit the mood of the day. In dry weather, it can produce excellent white and sparkling wines; at moderate humidity levels, whether due to the autumn fog or the influence of the ocean, it creates sweet, semi-dry, and dessert wine. It is a grape capable of taking on the profile of its terroir almost seamlessly, and allows its personality to mesh with its place—the French wine philosophy made manifest.

Terre de l’Élu

For Charlotte and Thomas Carsin, winemaking is many things—an interest, then a passion, then a commitment, then a profession. But first and foremost, it’s an adventure.

“My path to Clos de l’Élu began as a grape picker in Burgundy,” Thomas shares. “I was studying tropical agronomy, but ultimately chose to specialize in wine and found work placements in Sonoma, where I learned a great deal about terroir and vinification.”

After that, he learned the retail side of the business in a Paris boutique and spent five years doing consultancy work in Champagne. By the time his stint as a journeyman was over, he had learned a very keen lesson about the ‘over-engineered wine industry’: He hated it. By then he was well-versed in ‘winegrowing empiricism’—the language of the vines and master the idea of terroir. He spent a few more years making wine in Provence, in the departmente of Var, but it wasn’t until 2008 that he was able to acquire a domain and produce wine on his own terms: “Acquiring Clos de l’Élu, in the heart of the Layon valley, was a dream come true.”

Thomas and Charlotte Carsin, Terre de l’Élu

Charlotte’s road to the winery was a bit more straightforward. Having worked in communication, with specialized interest in pairing food and wine, she has learned the technical angles hands-on. Of course, her professional chops allow her to serve as the winery’s administrator, in the sales and marketing of the winery, and especially brand image, packaging, events, and communication methods.

As to the estate, Terre de l’Élu is in Saint-Aubin de Luigné; the vines grow on the outskirts of the village between Chaume and Ardenay, on the right, south-facing side of the Layon River. Soils here are classic Anjou Noir, full of volcanic rocks, sandstone and quartz.

* A Note on de l’Élu’s ‘VdF’ label status: The domain was originally called Clos de L’Elu, but in 2018, frustrated by politics and arbitrary restrictions of the Anjou appellation, they decided to leave the AOP. This meant more freedom to grow the grapes they wanted and vinify them as they wished, but also necessitated a name change, as they were no longer allowed to us any word referencing the location – including their famous walled Clos. So the domain became Terre de l’Élu, the wines were labeled Vin de France, and a new era of experimentation and creativity began. Thomas affirms their decision in saying, “What counts the most is to make the wine of the terroir.”

•Bottle 3•

•Bottle 3•

Terre de l’Élu ‘Bastingage’, 2021 VdF Loire-Anjou ‘Chenin’ ($32)

Bastingage is Terre de l’Élu’s flagship wine, and the term fits since a bastingage is the railing that surrounds a ship’s deck. The grapes come from three parcels, Les Barres, L’Aiglerie and Chaumes, vinified separately and combined only at the final assemblage. The grapes are hand-harvested with meticulous sorting done in the vineyard using multiple passes followed by slow, direct pressing and natural fermentation on native yeast. The wine spends one year on lees, then in blending vats for another three months. It shows the superb minerality that is typical of schist terroirs, but it is soften by ripe tones of citrus and candied apple.

•Bottle 4•

•Bottle 4•

Terre de l’Élu ‘Ephate’, 2019 VdF Loire-Anjou ‘Chenin’ ($73)

‘Ephata’ means ‘be opened’ in Greek, although you can resist this directive for many years and not be disappointed. The wine is among those built for the long haul, with aggressive acidity and a tannic-like quality. The grapes come from 70-year-old vines with a ludicrously low yield of 20 hectoliter/hectare. Grapes are hand-harvested and gently pressed, then allowed natural fermentation for six months in 1000 liter sandstone amphorae, followed by one year in 1400 liter terracotta amphorae with ouillage (topping off) done every two months. This is followed by another 6 months back in the 1000 liter sandstone amphorae. The wine is smooth and complex with notes of damp stone and ripe pear with slight spice hints of anise and angelica.

Domaine Belargus

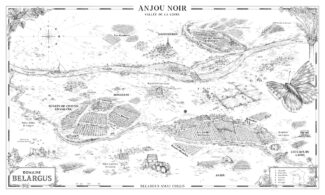

Many French wineries trace their origins back centuries. The owner of Belargus (named for the colorful butterfly that flits about the estate) plays an even longer game: “This began in the earliest hours of earth,” says Ivan Massonnat. “Over hundreds of millions of years, the Armorican Massif eroded into hillsides—terrestrial islets with complex geography, and between the Loire and Layon rivers, Anjou wine was born … and in its wake, Belargus.”

Few vignerons in Anjou are as determined to explore the region’s myriad possibilities as Massonnat—the domain is a collection of Grand Crus, single-plots, monopoles and micro-climates, using Chenin as the sole instrument. “Our vines are distributed around three main islets (Savennières, Quarts-de-Chaume and the Layon Valley), themselves composed of singular terroirs, each precisely defined by their exposure, their subsoil or their slope.”

This musical mosaic of terroirs is expressed through a collection of cuvées that highlight three main islets, Savennières, Quarts-de-Chaume and the Layon Valley. Says Massonnat: “We employ a single-plot approach inspired by the climats of Burgundy. Among our most remarkable terroirs is the Grand Cru Quarts-de-Chaume, the estate’s center of gravity with twenty-six acres in one piece. Our first monopole is Coteau des Treilles, a wild and steep hillside located in the heart of a classified Regional Natural Reserve; our second is Clos des Ruchères in Savennières, planted on a rare hillside of purple schists.”

Massonnat is as beholden to vintage as to terroir, and every year, through respect of the same, he produces dry white wines, but in exceptional years, he relies on the magic of botrytis to create sweet wines.

Ivan Massonnat and Jo Pithon, Domaine Belargus

He’s also sold on the virtues of the collective approach, and since its inception, he has brought together young talents like winemaker Adrien Moreau and vineyard manager Amaury Chartier along with some iconic Loire pioneers like Jo Pithon and Guy Bossard. This faith in collective energy has seen Massonnat preside over the international Anjou festival called Paulée d’Anjou and spearheading a tireless struggle to get ‘Ronceray’ officially recognized as a Cru.

“Belargus is a 100-year project.,” Massonnat says. “Everything we do, we have that horizon.”

•Bottle 5•

•Bottle 5•

Domaine Belargus ‘Ronceray’, 2020 Anjou Blanc ($71)

Ronceray is the name coined by Chaume growers to describe dry Chenin made in this sweet-only appellation, which is why the declassification of the 100% Chaume fruit—named, ironically, for a 17th century monastery that made dry wines on the Chaume hill long before it became an officially-mandated appellation for sweet wine. From 30-year-old vines grown in loamy clay, schist, sandstone and puddingstone, the wine is an exotic array of aromas ranging from candied mango and warm hay to quinine and barley.

Domaine Belargus ‘Rouères’, 2020 Anjou Blanc ($108)

Domaine Belargus ‘Rouères’, 2020 Anjou Blanc ($108)

Les Rouères is an east and southeast-facing lieu-dit in Quarts-de-Chaume, where the soils are dominated by puddingstone rather than schist. This soil type is a naturally loose conglomerate with various sizes notable for radiating daytime heat well into the evening, so while this site might not have the warmest exposure in Quarts-de-Chaume, the terroir makes up for it. Domain Belargus owns a little over seven acres of vines in this lieu-dit and makes two cuvées—this dry wine wears the Anjou appellation and a late-harvest Quarts de Chaume. The dry version is intensely aromatic with peach compote and apple butter intertwined with delicate mineral notes, structured to improve for a decade or more.

Domaine Belargus ‘Veau’, 2020 Anjou Blanc ($126)

Domaine Belargus ‘Veau’, 2020 Anjou Blanc ($126)

Says Ivan Massonnat: “Le Veau is one of the three plots originally listed in the decree creating the Quarts-de-Chaume appellation. Our plot covers the most part of this small area, exposed to the west. Its name comes from the shape of the plot, which constitutes a small valley where the soil is very thin—non-existent in some parts—as the plot rests on a flush schist area, providing mineral tension and long aging potential to the wine.”

First produced in 2019, the cuvée is aged in vats and barrels for a minimum of one year and represents the quintessence of Chenin cultivated on black schist. It exhibits subtle purity and refreshing minerality blended with quince, apple skin and honey followed by a lingering tannin grip and salinity.

Domaine Belargus ‘Quarts’, 2020 Anjou Blanc ($144)

Domaine Belargus ‘Quarts’, 2020 Anjou Blanc ($144)

‘Les Quarts’ is the lieu-dit from which the Quarts-de-Chaume appellation draws its name. In fact, until the French revolution stopped all that elitist stuff, the lords of Haute-Guerche (who farmed the vineyard) paid the Ronceray Abbey with ‘the best quarter of the harvest’ or, the ‘Quarts-de-Chaume.’ Massonnat’s portion is about half the 20-acre vineyard, with southern exposures, where the soil is predominantly Precambrian schist. This comes through in the crystalline purity of the bouquet, calling to mind peach candy, crushed stone and lightly-salted grapefruit sections.

Coteaux-du-Layon: The Magic Of Botrytis Creates Sweet Chenin

You say botrytis, I say noble rot (the Germans say edelfäule and the Hungarians, aszúsodás) but fair to say, nobody is going to call the whole thing off … except Mother Nature. As most students of the vine know, botrytis is a beneficial form of grey fungus that forms late in the season in certain areas when weather conditions are right—humid, damp, but not too damp, then followed by a dry spell. Grapes thus affected become raisined, produce concentrated wines that are among the most opulent, expansive and hedonistic wine in the world. Included in the list of botrytised wines are the Sélection de Grains Nobles of Alsace, Germany’s sweeter styles, Sauternes in Bordeaux and Tokaji in Hungary.

And, of course, the honeyed gems of the Loire. Coteaux-du-Layon is not the only sweet wine appellation in Anjou, but it is the biggest, encompassing 27 communes to the south of Angers, accounting for roughly 4,200 acres of vineyards. No fancy-pants blends here—all Coteaux-du-Layon wines are made from Chenin.

The region’s reputation for sweet wines is due in large part to its topography, the result of the local river systems, including the Layon, which has carved out south-facing slopes and sheltered mesoclimates protected from the cold continental winds that blow in from the north and east. The botrytis, so indispensable for the wine, is the result of morning mist rising from the rivers. As is the case with German wines, the sweetest wines of the Coteaux are also the most expensive and labor intensive. They are made from grapes harvested in multiple passes through the vineyard, with pickers collecting only grapes affected by noble rot.

•Bottle 6•

•Bottle 6•

Domaine Belargus ‘Layon’, 2018 Coteaux-du-Layon ($42) 375 ml

Another interpretation of Chenin from south-facing, schistous slopes above the Layon River. Radiant orange in color and brilliantly alive with apricots intertwined with fresh ginger and beeswax, this is a seamless moelleux with fine crystalline structure and the refreshing balance of acidity.

Domaine Belargus ‘Écharderie’, 2018 Coteaux-du-Layon Premier Cru Chaume ($108)

Domaine Belargus ‘Écharderie’, 2018 Coteaux-du-Layon Premier Cru Chaume ($108)

Écharderie is a southwestern-facing lieu-dit that stands in the spot where the cellars of the seigneurs de la Haute-Guerche were once located. Domaine Belargus farms slightly under an acre of Chenin in this Chaume Premier Cru, planted on a mix of schist, alterite and puddingstone soils. The wine shows light marzipan, dried apricot, honeysuckle and sweetened green tea that shine through to an electrifyingly acid and salty-sweet finish.

Domaine Belargus ‘Les Rouéres’, 2018 Quarts-de-Chaume Grand Cru ($126) 375 ml

Domaine Belargus ‘Les Rouéres’, 2018 Quarts-de-Chaume Grand Cru ($126) 375 ml

‘Les Rouères’ is one of the three plots originally listed in the decree that created the Grand Cru Quarts-de-Chaume appellation. “Our plot covers nearly three hectares (7.4 Acres),” says Ivan Massonnat, “exposed on the southeastern slope of the rump of Quarts-de-Chaume where the puddingstone soils give a spherical and solar character to the wine. The magic the terroir when exposed to the morning mists of the Layon and aerated by constant winds results in a botrytis of rare concentration.”

This is a sweet and honeyed wine, juicy with candied lemon rind and orange marmalade caught in a noble web of botrytis.

Domaine Belargus ‘Les Quarts’, 2018 Quarts-de-Chaume Grand Cru ($144) 375 ml

Domaine Belargus ‘Les Quarts’, 2018 Quarts-de-Chaume Grand Cru ($144) 375 ml

Like Les Rouères, Les Quarts Grand Cru is only made in exceptional vintages like 2018, where favorable weather conditions throughout the year yielded concentrated wines a bit lower in acidity than usual. This is a full, unctuous wine with significant aging potential; it shows gingerbread, balsamic apricot and nougat with earthy minerality and a long, bright finish.

- - -

Posted on 2024.01.26 in Coteaux-du-Layon, Quarts-de-Chaume, Savennières, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Loire

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Aligote, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Cinsault, Clairette, Corvina, Counoise, Dolcetto, Erbamat, Ferrol, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Gamay, Garnacha, Garnacha Tintorera, Gewurztraminer, Graciano, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malbec, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marcelan, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montònega, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscat, Natural, Niellucciu, Parellada, Patrimonio, Pedro Ximénez, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Pouilly Fuisse, Pouilly Loche, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Riesling, Rondinella, Rose, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sagrantino, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Sciacarellu, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Search