Southeast is Southeast, and Southwest is Southwest – Rosés From The Two Southern Opposite Ends of France: The Mediterranean Coast and The Atlantic Coast (A Baker’s Dozen $297)

“A rose is a rose is a rose” is a poetic riff about universal truth by Gertrude Stein, but add an accent aigu to the final ‘e’ and all bets are off. As a style of wine, rosé is as diverse as the terroir which produces it, and even the name ‘rosé’—French, of course, for pink—belies reality as colors range from ruddy, blood-orange-tinted redcurrant in Tavel to the pale melon and peach whispers of Provence.

This week’s Baker’s Dozen are rosés that span hue and heft of pink(ish) wines from the south of France—some delicate enough to grace a summer patio without accompaniment, others rich enough to stand up to complex cuisine.

Vintage 2021 – (Climate) Change is Afoot

Over the past 30 years, the average temperature in southern France has risen by 1.5 degrees Celsius and predictions suggest that by the end of this century, up to two months each year will suffer drought. And it’s not just heat that is spawned by climate change; hailstorms in the spring are become ever more frequent and wetter, milder winters allow pests to survive that might otherwise have been killed.

2021 proved to be the poster child for the difficulties that climate change are throwing at winemakers throughout France, particularly when it comes to their beloved rosés. In 2021, a wet winter was followed by an unseasonably hot March, which launched early growth. There followed an unexpectedly intense and extensive frost in early April, significantly reduced volumes of Grenache and some Syrah, especially in the western half of the region. The summer was dry, although late-August rain was welcome, though heavy, localized hail in late August and early September decimated some vineyards in the central region. Massive forest fires north of Saint Tropez and along the northern edge of the Massif des Maures further reduced volumes, with some parcels burnt and others suffering from smoke taint.

Some producers have adapted technique to maintain house styles while others are experimenting with new sites and varieties. Flexibility was key for each of the producers represented in this package, and the quality reflected in the wines they released in 2021 shows that the human touch is, under current conditions, sufficient to offset many of nature’s temper tantrums.

The offered 13-bottle package is comprised of one of each of the following wines at $297.

Southeast Regions

The Mediterranean, A Place in The Sun

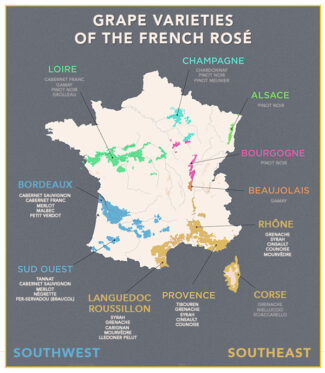

The Mediterranean Sea takes a sizeable chunk out of France’s hindquarters, and the bite-shaped crescent contains a few of the most dynamic winegrowing regions in the country. Clockwise, from just north of Spain, Languedoc-Roussillon is a swarthy appellation known for Grenache and Carignan blends—two varieties that love the hot coastal sunshine. The insanely productive Languedoc-Roussillon AOPs account for more than a third of the country’s wine output. On the map, Provence comes next, located at the southern end of the Rhône Valley. Provençal wine has been made for over 2,600 years and it’s the only region in France that dedicates almost all of its production to rosé.

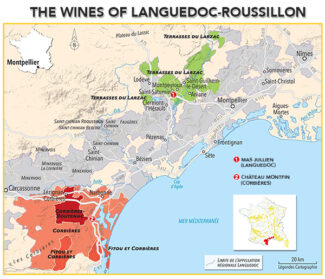

Languedoc-Roussillon

Sun-baked and sensual, threaded with rivers and capped by the mountains of Corbières, Languedoc-Roussillon relies on over a hundred grape varieties to produce more than a third of all French wine. Historically, this wine was copious, inexpensive and rather forgettable—everyday wine for the tables of ordinary people. Since the mid-twentieth century, however, with the advent of irrigation in the foothills and coastal plains of Southern France coupled with improved techniques, the region now boasts fewer vines that produce wines of increasing quality. A jigsaw of soils and a broad swath of microclimates creates ideal terroir for the warm-weather, full-bodied varietals often associated with the Rhône, while sharp diurnal shifts allow for the preservation of aroma and natural acidity, resulting in wines of extraordinary balance. A further plus is that Languedoc-Roussillon’s hot, dry climate discourages the growth of mildew and fungi, making synthetic pesticides and herbicides less necessary. As such, it has become a proving ground for organic and biodynamic producers.

Mas Jullien (Languedoc)

Olivier Jullien grew up in troubled vineyards worked by his father and grandfather. In the 1970s, Languedoc was beset by economic woes driven by decades of over-cropping to produce cheap wine. In a world that was increasingly turning to quality, Languedoc was reduced to an afterthought and many of the children produced by this generation opted for careers far from the wine cellars. Olivier hung on with a firm belief that Languedoc was capable of greater things. After earning a degree in viticulture and oenology, he began farming some of his family’s vineyards and scouring the area for the best vineyards to purchase. He was only twenty years old when he converted the outbuildings on the family estate into a cellar and began vinifying and bottling his own wine under the Mas Jullien label.

Today, Mas Jullien contain 37 acres scattered around the village of Jonquières, north of Montpellier, 25 miles inland from the Mediterranean Sea. The vines grow on the rocky terraces of the plateau of Larzac at the foot of Mont Baudille, reaching altitudes of 3000 feet, the upper limit of vine cultivation.

1 Mas Jullien, 2021 Languedoc Rosé ($31)

1 Mas Jullien, 2021 Languedoc Rosé ($31)

A saignée rosé made from juice that is bled off the skins of red grapes from Jullien’s vineyards on the Terrasses-du-Larzac. A blend of Cinsault, Carignan and Mourvèdre, though the blend can change from vintage to vintage. Fermentation takes place in stainless steel with native yeast, aging in Stockinger foudres of mixed ages. It is a structured and somewhat wild wine of deep, earthy complexity showing garrigue and wet stone behind strawberry and watermelon.

Château Montfin (Corbières)

Corbières is one of the most productive wine-producing regions in Languedoc-Roussillon. With more than 2000 growers, 300 private wine producers, and over 30 cooperatives, the annual output of wine is over 73 million bottles; roughly on par with the entire state of Oregon. Most of the output is red, rustic and filled with southern spice, made from Grenache, Syrah, Mourvèdre, Lladoner Pelut and Carignan. But Rosé Corbières has gained an international reputation for quality. Corbières is a pastiche of soils and subsoils—volcanic upheavals have exposed layers from many geological periods, and 11 unique terroirs have been identified.

Old vine is the name of the Montfin game, and when Jérôme Estève took over the domain in 2002, he found parcels of Carignan that had been planted in the 1930s. By Corbières standards, his production is small with yields highly restricted, and, since 2009, the 50-acre estate has farmed Grenache, Syrah, Mourvèdre and sixty-year-old Cinsault vines organically. They also practice biodynamics, spraying an infusion of nettle and comfrey on the vines and using green manure on to add organic material and humidity to the subsoil, and planting various type of trees around the vines to recreate equilibrium in the ecosystem.

2 Château Montfin ‘L’Étang Danse’, 2021 Corbières Rosé ($17)

2 Château Montfin ‘L’Étang Danse’, 2021 Corbières Rosé ($17)

Named after the ballet of flamingos on the lake of Peyriac, the wine is 50% Grenache Noir, 45% Cinsault and 5% Syrah. It is juicy and bright, with cranberry and pungent wild flowers on the nose, with supple raspberry and bitter orange throughout the palate, ending on with sharp salinity.

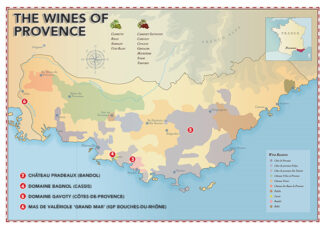

Provence

It’s hard to top Provence for sheer pastoral beauty, from its lavender fields to the hilltop villages and a landscape flecked with vineyards and orchards, everything behind a backdrop of the Mediterranean Sea. The vineyards of Provence snake along an area 125 miles long from east to west, and no Provençale vineyard is more than 25 miles from the Mediterranean. Vines here enjoy 3000 sunshine hours per year, along with an annual average temperature of 58°F while long, dry Mediterranean summers provide ideal harvest conditions in most years, leaving the majority of the region’s grape-growers free from worry about unwanted rot and vine disease.

Traditional varieties such as Carignan, Barbaroux and Calitor being gradually replaced by more commercially viable grapes like Grenache, Syrah and Cabernet Sauvignon. They are referred to as cépages améliorateurs (improver varieties) while some local varieties (Mourvèdre, Tibouren and Vermentino, known as Rolle) have retained favor among traditionalists.

Château Pradeaux (Bandol)

Bandol is an AOP within the greater Provence appellation; it is relatively small, covering fewer than 4000 acres. Rosé represents about a third of Bandol’s wine production, and—like the reds—they are generally a blend of Mourvèdre, Grenache and Cinsault. Protected from the north winds by the Montagne Sainte-Victoire and the Massif de la Sainte-Baume to the north and the Chaîne de Saint-Cyr to the west, Bandol offers growing conditions suited to extra ripeness, greater fruit weight and enhanced structure, especially for the rosé. Attesting to the refreshing quality of these blush wines, Alexandre Dumas portrayed his Count of Monte Cristo as enjoying a glass of Bandol rosé ‘bien frais.’

Situated on the outskirts of the town of Saint Cyr-sur-Mer directly on the Mediterranean Ocean between Toulon and Marseilles, Château Pradeaux has been in the hands of the Portalis family since the French Revolution. In fact, Jean-Marie-Etienne Portalis helped draft the Napoleonic Code and assisted at the negotiation of the Concordat under Napoleon the First. Today, the domain is run by Cyrille Portalis, who continues to maintain the quality traditions of his forbears, assisted by his wife Magali, and their sons Etienne and Edouard. Although vineyards are planted almost exclusively to old-vine Mourvèdre, Château Pradeaux Bandol Rosé is composed of Cinsault as well.

3 Château Pradeaux, 2021 Bandol Rosé ($37)

3 Château Pradeaux, 2021 Bandol Rosé ($37)

Among the richest rosés in Bandol, the vinification follows tradition: After a short maceration on the skins to extract light color, the juice is fermented at low temperatures to highlight freshness, fruit and bouquet. After being aged in stainless steel, the wine is bottled in the spring of the year following harvest. It is dry and full-bodied with mango, blood orange and white cherry flavors flanked with anise, honey cream and rose petal elements.

Domaine Bagnol (Cassis)

The entire vineyard area of Cassis is under five hundred acres, but most of the properties overlook the sea, which moderates the heat and creates an ideal climate for vine growing; the commune is known primarily for its herb-scented white wines, principally from Clairette and Marsanne (about 30% of Cassis production is rosé) and despite its name, it does not produce Crème de Cassis.

Sitting just beneath the imposing limestone outcropping of Cap Canaille, 700 feet from the shores of the Mediterranean, Domaine du Bagnol is the beneficiary of the cooling winds from the north and northwest and as well as the gentle sea breezes that waft ashore. Cassis native Jean-Louis Genovesi and his son Sébastien run the 18 acre estate.

4 Domaine du Bagnol, 2021 Cassis Rosé ($37)

4 Domaine du Bagnol, 2021 Cassis Rosé ($37)

Grenache, Cinsault and a touch of Mourvèdre; the wine is perfumed and with red-currant and strawberry aromas and provides a crisp and refreshing wash of citrus and crushed stone and slate minerality.

Domaine Gavoty (Côtes-de-Provence)

The massive Côtes-de-Provence sprawls over 50,000 acres and incorporates a patchwork of terroirs, each with its own geological and climatic personality. The northwest portion is built from alternating sub-alpine hills and erosion-sculpted limestone ridges while to the east, and facing the sea, are the volcanic Maures and Tanneron mountains. The majority of Provençal vineyards are turned over to rosé production, which it has been making since 600 B.C. when the Ancient Greeks founded Marseille.

Roselyn Gavoty (the eighth generation of Gavoty to helm her family’s Roman-era farm; her ancestor Philémon acquired it in 1806) is on the cutting edge of viticulture. Situated along the Issole River in the northwestern corner of the Côtes-de-Provence, surrounded by oak and pine forests, the Gavoty family has worked the land without synthetic chemicals for decades, obtaining organic certification in recent years. The vineyard covers 150 acres in the commune of Cabasse (‘harvest field’ in the old Provençal language). Roselyn says, “Our vines are planted on clay-limestone soil, and produce a majority of rosé by the saignée method, involving involves bleeding off a portion of red must to create structure and depth.”

5 Domaine Gavoty ‘Récital’, 2021 Côtes-de-Provence Rosé ($23)

5 Domaine Gavoty ‘Récital’, 2021 Côtes-de-Provence Rosé ($23)

Roselyn’s grandfather Bernard Gavoty (1906-1980) was a renowned classical music critic for France’s newspaper ‘Le Figaro’, and the name of this cuvée pays homage to the importance of music in the family’s history. Comprising equal parts Grenache and Syrah, plus around 10% Carignan, and produced via direct pressing, ‘Récital’ delivers the ethereal color, lip-smacking salinity, and bright fruits one expects from the appellation, but with a sumptuousness of texture and a swelling, clinging finish that is all Gavoty. It offers spectacular value, as well as notable personality for its category.

Mas de Valériole (IGP Bouches-du-Rhône)

‘IGP’ (Indication Géographique Protégée) is a Europe-wide category that focuses on geographical origin rather than style and tradition, giving winemakers greater stylistic freedom than ‘AOP’ (Appellation d’Origine Portégée). As such, the boundaries of Bouches-du-Rhône are geographical, with the Durance river delimiting the north and the Rhône river making up the western border. The soils of the region tend to be poor, free draining and made up of anything from limestone-clay to gravel and sandstone; the lack of water forces vines to produce more concentrated grapes, leading to more concentrated and flavorful wine.

Mas de Valériole’s eighty-acre vineyards reflect this diversity in multiple soil types: sand, clay, limestone, and alluvial loam deposited by the Grand Rhône. The reliably steady mistral wind blowing in from the Mediterranean mitigates the heat and facilitates the domain’s chemical-free approach to farming while ensuring modest alcohol levels in the wines. The property was acquired by the Michel family in the late 1950s and is now run by Jean-Paul and Patrick Michel. Produced from a variety of cépages, including Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, plus crossings like Caladoc (Grenache and Malbec) and Marselan (Grenache and Cabernet Sauvignon) which are particularly well-suited to the Camargue’s climate, Mas de Valériole’s wines combine the breezy freshness of Provence with a sense of wildness and an underlying salinity that is representative of Bouches-du-Rhône.

6 Mas de Valériole ‘Grand Mar’, 2021 IGP Bouches-du-Rhône – Terre de Camargue Rosé ($23)

6 Mas de Valériole ‘Grand Mar’, 2021 IGP Bouches-du-Rhône – Terre de Camargue Rosé ($23)

‘Grand Mar’ Rosé is 100% Caladoc, fermented with indigenous yeasts (unusual for rosé production) in stainless steel tanks to preserve freshness. The wine is enticing with vibrant notes of ruby-red grapefruit and white peach behind crackling acidity—a wine that never met a salmon dish it did not love.

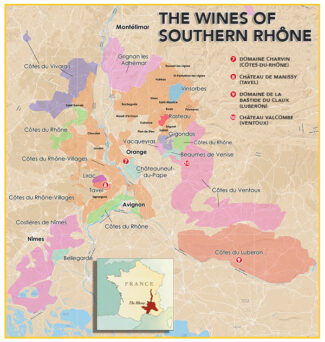

Southern Rhône

From mighty Châteauneuf-du-Pape to easy-drinking Côtes-du-Rhone, the shared characteristic of wines from Southern Rhône are fruit-centered displays of lusciousness, spice and earth. Most of the massive red wines are suited to cool weather, but this is by no means the case for the rosé produced along the Mediterranean coast.

So dark in color are some of the Southern Rhône’s most celebrated rosés that they nearly defy the ‘blush’ concept. But the term itself isn’t fair to the category; in it very soul, rosé qualifies as neither red wine nor white wine. It may be (although rarely is; the practice is frowned upon) a blend of the two, but in nearly all cases, it is produced by crushing red-skinned, white-fleshed grapes and allowing a period of maceration lasting from a few hours to a couple days in which the juice is ‘dyed’ to a specific level; alternately, there is méthode saignée, which is essentially fermented free-run juice from red wine pressings.

Domaine Charvin (Côtes-du-Rhône)

To wear the Côtes-du-Rhône label, the wine must come from a vast 140,000 acre area around the southern end of the Rhône Valley. Among the best value rosés in a category already saturated with bargains are the blush wines of this generic appellation; the offerings cover the spectrum of colors delineated in the Provençal color chart, pale pink to rich raspberry, with a palate that tends toward the full-bodied and exceptionally fruity. Novices have been known to ask if rosé is simply a blend of red and white grapes, and in the case of Côtes du Rhône rosé, up to 20% of the cuvée may be composed of white varieties.

Established in 1851 in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Domaine Charvin is currently owned and operated by Laurent, the sixth-generation Charvin to run the domain but the first to commercially market a proprietary bottling. His meticulous attention to detail sees his harvest entirely hand-picked and sorted and bottled without filtration.

7 Domaine Charvin, 2021 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($21)

7 Domaine Charvin, 2021 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($21)

45% Grenache, 45% Cinsault, 10% Mourvèdre. Laurent Charvin’s 2018 Rosé is a forward, deliciously quaffable rosé that sports a light mango pink to go with upfront notes of candied cherries, melon, lavender and Provençal herbs.

Château de Manissy (Tavel)

Located on the bank of the Rhône River opposite to Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Tavel represents a triumvirate of terroirs: The lowest portion sits on sandy soils with very little organic matter and produces aromatic, low-alcohol wines; Lauses—a type of shallow soil covered with stone tiles mixed with red clay on a limestone bedrock—results in wines of great finesse and pronounced minerality; finally, Les Vestides, where the soil is blanketed with limestone rocks and produces robust, structured wines slightly higher in alcohol. To say ‘Tavel rosé’ is to repeat yourself since, by law, all wine from Tavel is rosé.

Château de Manissy was built in the middle of the 18th century by the Congregation of Missionary Fathers of the Holy Family who planted the first vines in 1916. Having developed a loyal following for their Tête de Cuvée, the priests turned over the managing of the estate to Florian Andre in 2004. Among the many improvements he brought to the site was a switch to minimal interference agriculture and in 2012, he certified organic and began producing some exceptional wines from the limestone and clay soils.

8 Château de Manissy ‘Cuvée des Lys’, 2021 Tavel ($19)

8 Château de Manissy ‘Cuvée des Lys’, 2021 Tavel ($19)

60% Grenache, 20% Syrah and 20% Clairette from vines that average 45 years old grown in clay, river rock and fine-grained sand. It opens with aromas of white flowers and spring strawberries, filling out in a silky blend of watermelon and pomegranate; it is rich in minerality and intriguingly peppery on the finish with notes of honeysuckle and lime.

Domaine de La Bastide du Claux (Luberon)

The list of grape varieties permitted in the relatively youthful Luberon appellation (created in 1988) is long, but Syrah and Grenache dominate plantings and must both be present in reds from here. Mourvedre is also considered a primary red grape. Rosé represents about half the region’s output, and are generally made from the permitted red grapes, although they may legally incorporate up to 20% of white varieties, primarily Grenache Blanc, Clairette, Bourboulenc, Ugni Blanc and Vermentino.

Domaine de La Bastide du Claux was born in 2002 when Sylvain Morey—whose family’s roots in Chassagne-Montrachet goes back 400 years—uprooted. In the hills of Luberon, he chose to transplant some of his Burgundian know-how to Provence’s up and coming appellation. In the heart of the Luberon Natural Park, Morey cultivates a fragmented vineyard spread over 42 acres. Finding Luberon’s rich combination of soils, climates and exposures suited to a number of different grapes, he planted 14 varieties, each location chosen with circumspection. “When I arrived, there were not many growers bottling their own wines,” he says. “The vast majority of the production in Luberon was made by local cooperatives, and many of them valued quantity over quality and began to replant vineyards so that they could produce the maximum amount of grapes possible and save money with machine harvesting. These trends made it possible for me to affordably purchase interesting, low-yielding old-vine parcels that were no longer valued.”

9 Domaine de La Bastide du Claux ‘Poudrière’, 2021 Luberon Rosé ($22)

9 Domaine de La Bastide du Claux ‘Poudrière’, 2021 Luberon Rosé ($22)

50% Grenache from 55-year-old vines, 30% Cinsault, and 20% and Syrah, from south facing vines around the villages of Peruis and Ansouis. The grapes were pressed directly, the majority without maceration, with a portion of Grenache and Cinsault spending six or so hours on their skins after the pressing. Everything is done in cement and the wine ferments naturally, resulting in a great mineral character, showing its soil influence clearly and offering subtle red fruits and vigorous acidity on the palate along with the salty tang that typifies Mediterranean rosé.

Château Valcombe (Ventoux)

Ventoux is a large wine region in the far southeast of the southern Rhône, 25 miles northeast of Avignon and bordering Provence. Covering 51 communes, the vines are planted on the western slopes of Mt. Ventoux, a sort of ‘stray’ Alp removed from the range and towering over the landscape for miles around. Ventoux terroir and varieties are typical for Rhône, although noteworthy are the region’s Muscat produced for table grapes, which has its own AOP—Muscat du Ventoux.

Originally owned by Paul Jeune of Domaine Monpertuis, he opted to sell to Luc and Cendrine Guénard who worked under Jeune’s tutelage during the transition period. They now are proudly independent vignerons with a compulsion to further improve this jewel; their first efforts can be seen and tasted in the 2009 vintage. Certified organic in 2013, the 70 acres of Valcombe are situated in the shadow of the mountain, reaching one thousand feet. Four red grape varieties (Syrah, Carignan, Grenache and Cinsault) balance four white grape varieties (Clairette, Grenache Blanc, Roussanne and Bourboulenc); many vines over sixty years old, although parcels of Carignan and Grenache were planted in 1936. Soils are essentially limestone covered with the area’s famous galets, although deep in the subsoil, an unusual blue-inflected clay helps define the unique characteristics of Valcombe wines.

10 Château Valcombe ‘Epicure’, 2021 Ventoux Rosé ($20)

10 Château Valcombe ‘Epicure’, 2021 Ventoux Rosé ($20)

Vinified via the direct press method from a blend of 60% Grenache, 20% Cinsault, 10% Carignan and a touch of Clairette; all vines are of an average age of 40 years. It has a rich, focused rich texture with strawberry and peach in the foreground and an earthy and intriguing dose of eucalyptus behind.

Southwest Regions

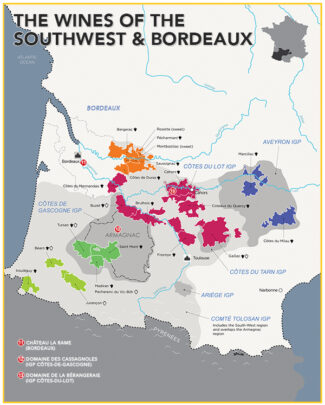

The Atlantic’s Moderating Influence

Known as ‘France’s Hidden Corner’, Southwest wine region is tucked away between the Pyrénées to the south, Bordeaux to the north and the Atlantic Ocean on the west. There is no reason for the secret not be shared, though—there are twice as many acres under vine here than in Burgundy, making it the fifth largest growing region in the country. The appellation is generally subdivided into chunks, Bergerac/ Dordogne River, Garonne/Tarn and Lot. There are also some larger areas with less restrictive vineyard and winemaking regulations referred to as IGPs as defined above. The climate is maritime, with the Atlantic Ocean providing both warmth in winter and cooling influences in summer. Vineyards can be found on the alluvial terraces of the region’s many rivers, where gravelly soils and sandy loess soils provide a well-drained environment.

Château La Rame (Bordeaux)

The Bordeaux AOP is the most widespread generic appellation in the Gironde department and includes wines produced throughout the entire department on all types of soil legally entitled to produce wine. Winegrowers must cope with this wealth of possibilities by choosing the grape varieties best adapted to each terroir, which can then be totally given over to the AOP Bordeaux or shared with another appellation. The areas entitled to the Bordeaux appellation were defined in an official decree dated 14 November 1936. Red wine vineyards cover nearly 10,000 acres and account for over 50% of all wine produced in Bordeaux. In contrast, Bordeaux rosé is made from around 12,000 acres.

Among the oldest and most renowned properties in the Sainte Croix du Mont appellation, Château La Rame has been recognized throughout its history as one of the prime sites for producing outstanding wine, with gold medals at exhibitions in Bordeaux in 1895 and in Paris in 1900. The estate was purchased by Claude Armand, the father of the current owner, Yves Armand, at a time when the property had fallen out of favor through neglect.

The château’s fifty acres are set on a clay-limestone soil blessed with an exceptional substratum marked by a bed of fossilized oysters dating from the Tertiary era. The hillside vineyards overlooking the Garonne River (and facing full south as they slope down towards the river) are planted to white grapes, while in the sandier soils where the land slopes toward the river, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon are planted and are used to produce Bordeaux Rouge and Bordeaux Rosé.

11 Château La Rame, 2021 Bordeaux Rosé ($24)

11 Château La Rame, 2021 Bordeaux Rosé ($24)

A typical Bordeaux blend, 80% Cabernet Sauvignon and 20% Merlot from a five acre parcel of younger vines on the flanks of a hill that descends towards the Garonne in the village of Sainte Croix du Mont. The wine is produced via the direct-press method and fermented in temperature-controlled vats for six months before it is bottled and released in the spring following the harvest. It shows ripe pear, lychee, lively citrus and a firm mineral backbone.

Domaine des Cassagnoles (IGP Côtes-de-Gascogne)

Côtes-de-Gascogne is the IGP title for wines that are produced in the area centered on the Gers administrative department; the catchment area covers all of Gers as well as smaller parts of Landes and Lot-et-Garonne. Across the appellation, the area is transitional, with the maritime effect of the Atlantic Ocean giving way to a more continental climate in the east of Gers. In the east, summers are warmer and drier, and the clay limestone soils retain water more effectively. Nearer the coast, loose, sandy soils with good drainage and high rainfall characterize the vineyards.

A practitioner of lutte raisonnée, Domaine des Cassagnoles’ 150 acres has been certified ‘Haute Valeur Environnementale’ since 2016. This is a voluntary qualification based on environmental themes: protection of biodiversity, a natural strategy to control plant diseases, organic management of fertilization and careful management of water resources. Cassagnoles is known for monovarietal wines using grapes indigenous to Gascony; the estate’s first 100% Colombard vintage was produced in the winery in 1980 and their 100% Gros Manseng has won high accolades.

12 Domaine des Cassagnoles ‘Rosé Plaisir’, 2021 IGP Côtes-de-Gascogne Rosé ($11)

12 Domaine des Cassagnoles ‘Rosé Plaisir’, 2021 IGP Côtes-de-Gascogne Rosé ($11)

60% Cabernet Sauvignon and 40% Merlot. Skin maceration occurs under controlled temperature to obtain color, followed by pneumatic pressing, juice selection, cold stabilization and fermentation under controlled temperature about 65°F. The wine is nearly garnet dark with garnet color with a lush palate of brambly summer berries and fresh watermelon, bracing acidity and enough texture to stand up to bold food flavors.

Domaine de La Bérangeraie (IGP Côtes-du-Lot)

Côtes du Lot, southeast of Bordeaux, is best known as the home of Cahors, where the inky and long-lived wines are built of Malbec. Reds make up the majority of production, accounting for around 60% of the output, while rosés make up around 13%. Lot is found on the very southern border of the Massif Central, the low mountain range that covers a large tract of southeast France. The topography is dominated by the Quercy Plateau, an undulating limestone plateau that is cut through by the Lot and Dordogne rivers. Most Lot vineyards are found in the valleys of these rivers, where the alluvial terroir is well-suited to viticulture.

André Berenger came to Cahors from Provence fifty years ago along with his wife Sylvie, who is originally from Champagne, and planted a vineyard near Grezels on the red clay/ iron stone soil known as Grèzes. Their two children, Maurin and Juline joined them in the family business, and today, along with their spouses, do all sustainable farming of the vineyards (Terra Vitis certified). All harvesting is done by hand, a disappearing practice in machine-friendly Cahors where harvesting is now done almost exclusively by machine. Bérangeraie wines are proof that hand-made artisanal wines of character and accessibility, are still being made in Cahors.

13 Domaine de La Bérangeraie ‘Tu Bois Coâ?’, 2021 IGP Côtes-du-Lot Malbec Rosé ($12)

13 Domaine de La Bérangeraie ‘Tu Bois Coâ?’, 2021 IGP Côtes-du-Lot Malbec Rosé ($12)

The frog on the label asks, “Tu Bois Coâ?”—an in-joke, perhaps—coâ is the French equivalent of a frog’s ‘ribbet.’ The wine is serious, though, offering a juicy nose of wild strawberry, gooseberry, watermelon and spice notes with crisp acidity and a long, easy-going palate.

- - -

Posted on 2022.08.05 in Bandol, Luberon, Ventoux, Côtes-de-Gascone, Côtes-du-Lot, Tavel, Côtes-du-Rhône, cassis, Corbières, France, Bordeaux, Wine-Aid Packages, Languedoc-Roussillon, Provence, Southern Rhone, South West | Read more...

The Task of Blending a Non-Vintage at Champagne Jacquesson: Prizing Excellence Over Consistency, Reflecting Main Vintage Than Replicating Flavors ($99)

On the northernmost limit of vine growing regions, where the average daily temperature is only 50°F, vintage variation is more pronounced in Champagne than in most other French wine appellations and as result, the technique of blending together several vintages to iron out the variants developed. Each domain evolved a dependably homogenous style synonymous with the name on the label. These house-style cuvées are non-vintage and represent a recognizable benchmark for each producer; they are based on a number of factors including winemaking decisions, dosage, and the grape varieties used in the blend.

A pioneering effort to swing the pendulum in a different direction comes from one of the oldest producers in Champagne, Jacquesson. Under the Midas touch of brothers Jean-Hervé and Laurent Chiquet (whose family bought the estate in 1978), a new meaning to ‘house style’ has emerged, stressing expression over consistency. With the 2000 vintage, Jacquesson announced that its 150-year-old non-vintage ‘Perfection Brut’ label would be retired and replaced with a numbered, vintage-based cuvée. The first was ‘728’, and each year since then, a new, subsequently-numbered-cuvée has been released representing the individual vintage on which it is based, but containing a different assemblage from reserve wines.

Critics have raved, including Antonio Galloni of Vinous Media, who maintains, “The 7-series wines are some of the best in Champagne and there is little doubt Jacquesson is now one of the elites.”

Champagne Jacquesson:

When Terroir is in The Blend

Krug is an old Champagne House, but Jacquesson is even older: Johann-Joseph Krug worked as Jacquesson’s accountant before leaving to start his eponymous winery. In the two hundred-plus years since its 1798 founding, Jacquesson has blazed many trails, beginning with Adolphe Jacquesson’s pioneering work alongside Dr. Guyot in training vine rows. He also established a base level of sugar in bottles, substantially reducing the problem of bottle explosion, and he was the first to patent the wire basket ‘muselet’ still used today to hold sparkling wine corks in place.

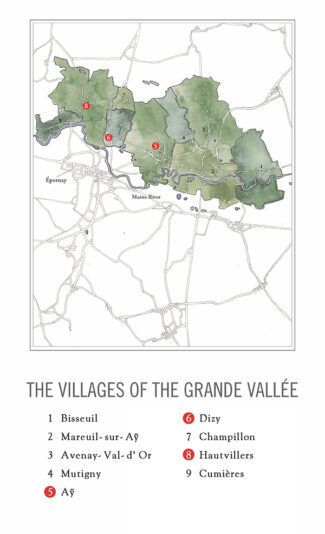

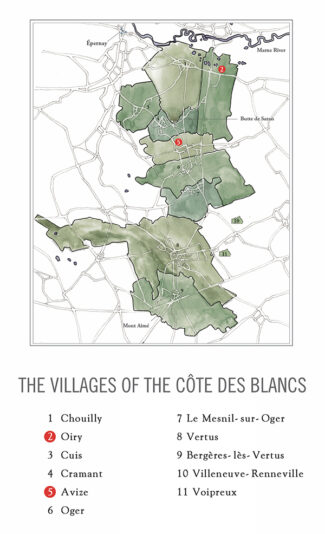

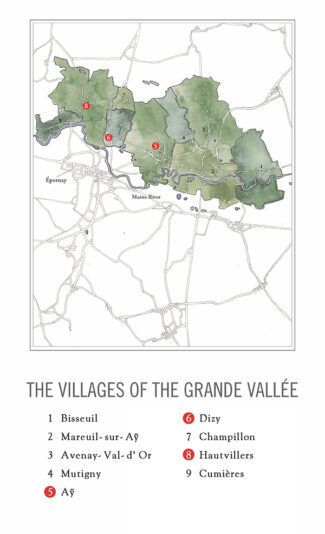

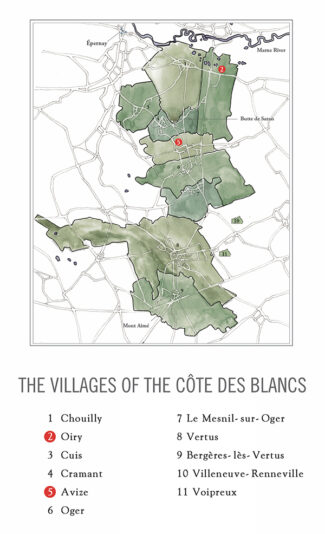

Into this tradition of innovation comes Jean-Hervé and Laurent Chiquet. Jean-Hervé, once the cellar master, now runs the commercial aspects of the business while his younger brother Laurent runs the production side in the role of chef de cave. The two work closely with their vineyard manager, Mathilde Prier who, in a given year, farms between 69 and 76 acres (acres vary based on annual contracts) in the Grand Cru villages of Aÿ, Avize, and Oiry, and in the Premier Cru villages of Hautvillers, Dizy, and Mareuil-sur-Aÿ.

Jacquesson has a small production facility in Dizy, where only juice from the first two pressings is used (the rest, the ‘taille’, is sold to négociants). All grapes come from either Grand or Premier Cru vineyards and perhaps most importantly, Jacquesson averages 7,000 bottles per hectare (2.47 acres) whereas the norm in Champagne is 10,000.

Earlier this year, Artémis Domaines, the holding company of François Pinault and owner of Bordeaux first growth Château Latour, acquired a minority shareholding in Jacquesson.

Redefining Non-Vintage Champagne: Introducing The 7-series

“Never exactly the same nor completely different. Why aim for average when you can achieve excellence?” – Jean-Hervé Chiquet

Champagne Jacquesson was founded during the French Revolution and the revolution remains alive and well with the Brothers Chiquet’s redefinition of non-vintage Champagne.

Philosophically, they have embarked on a mission to make Champagne as fine wine first and this has evolved into a twofold approach: First, a fundamental reconsideration of non-vintage wine and then, a move toward single-vineyard wines in a deep-dive into specific terroirs. Like most Houses, Jacquesson’s classic vintage Champagne was only made in the best years and was intended to be the best blended wine that the domain released to represent those years. But Jean-Hervé and Laurent decided to revamp the concept through their ‘7-series’ releases, intended to demonstrate Jacquesson’s best blended wine. 2002’s ‘Millésimés’ was to be Jacquesson’s final ‘vintage’ bottling; going forward, vintage wines would be limited to the four single-vineyard wines made only in stellar years and in very limited numbers, while the domain’s single blend would be the 7-series.

The three-digits numbering system of these wines has its origin in 1898, when the House revamped its administration and began keeping new records of every wine it made, beginning with Cuvée 1. Cuvée 728 represents, logically, the 728th cuvée the House has made.

Radical Change: Deconstructing Jacquesson

Today, the 7-series represents roughly 95% of Jacquesson’s production. The vineyard sources have essentially remained the same since the advent of this experiment: Parcels in the Marne Valley and along the Côte des Blancs growing in the Grand and Premier Cru communes of Aÿ, Dizy, Hautvillers, Avize, and Oiry.

The assemblage is shifting in a specific direction driven, in part, by global warming. For many years, the base varietal had been Chardonnay with roughly 20-25% each of Pinot Meunier and Pinot Noir. Gradually the percentage of Pinot Meunier is decreasing while Pinot Noir is increasing, so that today Meunier represents around 20% while Pinot Noir has increased to nearly 30%.

Single-vineyard releases represent around 5% of Jacquesson production and include the lieu-dit Corne Bautray in Dizy; two southwest-facing acres of vines planted in 1960 on clay soil capped by millstone over Campanian chalk. Also in Dizy, Terre Rouge is a three-acre plot consisting of 12,000 Pinot Noir vines planted in 1993. Champ Caïn in Avize is a lieu-dit located at the bottom of the slope in with a due south exposition where Jacquesson owns three acres of vines planted in 1962. The lieu-dit Vauzelle Terme is one of the most famous in the village of Aÿ with extremely chalky soils. The Chiquet brothers own ¾ acre of Pinot Noir vines planted in 1980, sitting midway up a south-facing slope.

“Because patience is always rewarded, each harvest has the chance to live two lives, with two different periods of aging,” says chef de cave Laurent Chiquet. Cuvée 7-series wines are first allowed a period of five years élevage, then the process of maturing continues another five for ten years in total; a process known as Dégorgement Tardif.

Fanatical Grower

“It’s the ties that bind the present to the past. The ties that bind the roots to the earth. The ties that bind the vines to the sky and the ties that bind men to the land allowing them to follow their dreams and their convictions. It is also a constant quest, year on year, to seek to reveal the full expression of their terroirs, to make the best wine that each vintage allows.” – Jean-Hervé Chiquet

Laurent and Jean-Hervé Chiquet

This is the force that animates the vine philosophy of Jacquesson and drives the women and men who tend them. Under vineyard manager Mathilde Prier, sustainable practices have become the Jacquesson norm, and one-third of Jacquesson’s vineyards are certified organic. No herbicide is used, and two-thirds of the vines are tilled while one-third is sown with cover crops. When fertilizers are used, they are entirely organic. Pruning is severe for low yields; there are no green harvests; canopy management is stressed to ensure minimal mildew and odium pressure, thus holding fungicide sprays to two per year.

Hands-off Winemaking

After harvest, the Chiquet brothers use century-old vertical presses rather than more abusive horizontal presses, whereupon the juice flows by gravity into steel tanks for 24 hours of settling, after which it is transferred to large neutral wood casks for several months to undergo alcoholic and malolactic fermentations. The initial fermentation is normally spontaneous while subsequent malolactic ferments are sometimes inoculated with neutral Champagne yeast that originally came from Cramant and Chouilly. The lees are stirred twice monthly to enrich the wine, a practice that has the additional benefit of providing a naturally reductive environment, keeping the need for SO2 additions to a minimum–one at pressing and another at disgorgement. The first racking normally occurs in April or May.

Malolactic fermentation is never blocked because doing so would require sulfur dioxide and because low acidity is not a concern on the 49th parallel. Starting with the 2016 vintage, élevage has lasted twelve months; the wine is put into bottle to age ‘sur latte’ after the next harvest. Since the fruit that makes the wine always attains an optimal level of ripeness, the dosage is typically in the extra-brut range of one to six grams of sugar per liter. Bottling is done without cold stabilization or filtration and care is taken with the labels to transparently detail all relevant information about the wine without marketing flourishes. (Jacquesson helped pioneer such honest and unadorned back labels.)

Today, the house produces an average of 250,000 bottles each year, roughly a 45% decrease from its production in the early 1990s. This is due to the shedding of buying contracts and to the intentional lowering of yields.

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 745, Extra Brut ($99)

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 745, Extra Brut ($99)

Based upon grapes from the low-volume 2017 vintage, completed with top reserve wines. 43% Chardonnay, 30% Meunier and 27% Pinot Noir with 66% of the harvest coming from Aÿ, Dizy and Hautvillers and 34% from Avize and Oiry. The winter and spring were exceptionally dry in this vintage, but in April, destructive frosts ravaged the vineyards, especially in the Côte des Blancs. Temperatures then rose and the weather remained good until July when rains set in, ending the growing season hot and very wet. Harvest ran from September 4 to September 13.

The nose shows spring flower blossoms, candied ginger and brioche, remaining elegant on the palate with light oak and mineral on the finish. A fine, complex and tense champagne profile.

Disgorgement: December 2021. Dosage: 0.75 gram/liter. 205,164 bottles produced.

En Magnum: Size Matters

Among the many reasons that magnums make spectacular vessels for Champagne, the fact that they are showy as hell and make great Instagram shots may be tops.

Although on a purely practical level, wine in a magnum is proportionately more expensive than single bottles, since it contains twice the wine and is typically more than twice the price. Not only that, but according to Moët & Chandon cellar-master Benoît Gouez, a magnum (despite containing twice the volume of a standard bottle) will always have the same neck size, meaning that each bottle’s air content is the same. As a result, the Champagne matures more slowly and over a longer period of time, resulting in a more complex and harmonious evolution. And at twelve glasses per magnum, it is a more convenient size for larger gatherings.

The following Champagnes are all 1.5 liter, magnums.

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 745, Extra Brut ($248)

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 745, Extra Brut ($248)

Grande Vallée de la Marne (66%): Grand Cru Aÿ, Premier Cru Dizy and Premier Cru Hautvillers. Northern Côte des Blancs (34%): Grand Cru Avize and Grand Cru Oiry.

Disgorgement: December 2021. Dosage: 0.75 gram/liter. 8,082 magnums produced.

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 744, Extra Brut ($248)

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 744, Extra Brut ($248)

Constructed around the 2016 vintage, the harvest draw was balanced at 55% from Aÿ, Dizy and Hautvillers and 45% from Avize and Oiry. The vintage began with a wet winter and spring with some serious frosts in late April. Spring finished sunny but cool, followed by a summer which was very hot and very dry. Picking began on September 19 and finished on October 6.

The wine shows aromas of pears, blanched almonds, freshly baked bread and mandarin; it is willowy and precise with a pinpoint mousse and a long chalky finish.

Grande Vallée de la Marne (55%): Grand Cru Aÿ, Premier Cru Dizy and Premier Cru Hautvillers. Northern Côte des Blancs (45%): Grand Cru Avize and Grand Cru Oiry.

Disgorgement: January 2021. Dosage: 0.75 gram/liter. 9,905 magnums produced.

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 743, Extra Brut ($232)

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 743, Extra Brut ($232)

Representing 2015, the harvest from Aÿ, Dizy and Hautvillers was 60% while Avize and Oiry was 40%. Winter and a large part of the spring were mild and wet; there followed a period of dry weather with spells of high temperatures which lasted until mid-August. The growing season ended with alternating periods of cool humidity and dry heat. Picking ran from September 10 through the end of the month. The harvest was very homogenous and produced perfectly ripe and healthy grapes in reasonable quantities with a sufficient level of acidity.

The wine boasts an elegant and toasty bouquet of pear, dried flowers and white fruit followed by ripe yellow plum, salted almond, candied ginger and buttered toast on the palate.

Grande Vallée de la Marne (60%): Grand Cru Aÿ, Premier Cru Dizy and Premier Cru Hautvillers. Northern Côte des Blancs (40%): Grand Cru Avize and Grand Cru Oiry.

Disgorgement: February 2020. Dosage: Zero. 10,013 magnums produced.

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 742, Extra Brut ($209)

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 742, Extra Brut ($209)

From 2014’s harvest, 59% Aÿ, Dizy and Hautvillers and from 41% from Avize & Oiry (41%). The winter was rainy and exceptionally mild, spring was hot and very dry, while July and August were cool and very wet, but a hot, dry and sunny September saved the year. The balance of alcohol and acidity was excellent and the health of the grapes was generally good. However, after picking, rigorous sorting of some parcels affected by small sources of acid rot was necessary. As a result, the Chardonnays were superb, as were the Meuniers, but above all, the Pinot Noirs delivered in fine style.

The wine offers up a bouquet of peach, apple, macadamia nuts over a beautiful base of chalk with a bit of buttery oak and a smoky top-note. On the palate the wine is deep and focused with impeccable balance, a refined mousse and a very long, complex and open finish.

Grande Vallée de la Marne (59%): Grand Cru Aÿ, Premier Cru Dizy and Premier Cru Hautvillers. Northern Côte des Blancs (41%): Grand Cru Avize and Grand Cru Oiry.

Disgorgement: November 2018. Dosage: 1.5 gram/liter. 9,902 magnums produced.

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 741, Extra Brut ($209)

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 741, Extra Brut ($209)

Disgorged in June 2018 with 2.5 grams per liter dosage, Cuvée No. 741 is built around the 2013 vintage. Both the winter and spring were cold and wet, delaying both budburst and flowering. When flowering did happen, grapes suffered from millerandage and coulure due to cool temperatures, significantly cutting yields. However, the reduced crops tended to ripen more easily during what would transpire to be a long, cool growing season. Conditions remained fairly consistent, and a warm, sunny September gave just enough warmth to rescue both the Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Many producers chose to pick later than usual to take advantage of the late good weather.

The wine unfurls in the glass with aromas of white flowers, fresh nectarine and peach, complemented by hints of warm biscuits and walnut oil. Vinous and concentrated, with a textural attack and a lively, focused core that’s underpinned by a bright spine of acidity and a long, sapid finish.

Grande Vallée de la Marne (66%): Grand Cru Aÿ, Premier Cru Dizy and Premier Cru Hautvillers. Northern Côte des Blancs (34%): Grand Cru Avize and Grand Cru Oiry.

Disgorgement: December 2017. Dosage: 2.5 gram/liter. 8,806 magnums produced.

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 740, Extra Brut ($219)

Champagne Jacquesson Cuvée No 740, Extra Brut ($219)

From the 2012 harvest from Aÿ, Dizy, Hautvillers, Avize and Oiry. The winter was long and cold; spring and early summer were very wet and there were severe attacks of mildew. However, a superb end to the growing season produced a small crop of remarkable quality. The Cuvée is completed with several reserve wines from previous 700 Cuvées.

The Champagne is nervy and poised from the first sip, expanding on the palate and unfolding into layers of lime zest and lemon curd, green apple and brioche. Intense waves of finely- minerality coat the tongue with contrasting, prickly acidity.

Disgorgement: January 2017. Dosage: 1.5 gram/liter. 7,696 magnums produced.

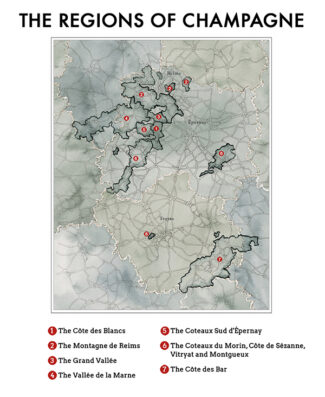

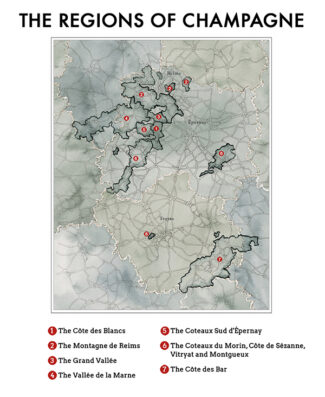

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it may take one a lifetime to understand it.

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

Beyond the overview lies a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that complement or contrast when final cuvées are created.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Epernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

- - -

Posted on 2022.08.01 in France, Champagne | Read more...

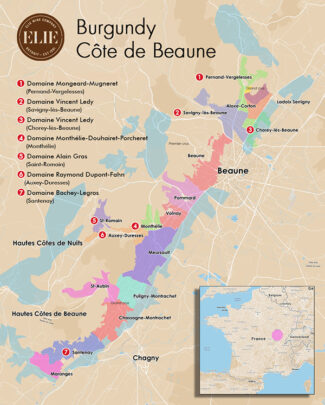

Back-Beaune Country Reds: Underappreciated Burgundy Regions With Energetic New Generation & Longtime Producers Leading a Quality Revolution. (7-Bottle Pack $378)

We have a bone to pick with anyone who badmouths backcountry Beaune red wine, and we make no bones about providing our supporting evidence.

The lesser known appellations in Beaune are producing increasingly discoverable Pinot Noirs whose prices remains in the range of the rational. Soil structure does not change, but overall terroir does: The climate is warming, and combined with the human touch—growing ever more experienced and technically savvy—marvelous red wines are being produced in places once considered marginal for Pinot Noir.

This package represents some of the best Beaune backcountry reds that we’ve encountered—they are wines from producers that consistently exceed expectations.

Build Beaune Backcountry Better

“Climate change is a fact,” says Laurent Audeguin, agronomist and enologist at the French Vine and Wine Institute. “As temperatures rise, the best vineyard sites become too warm. Vines are subject to increased risks of spring frost, sunburn and drought. The resulting wines, once defined by their elegance, subtlety and gracefulness, are getting riper by the year.”

As chilling as that prospect sounds, it appears unavoidable, and the silver lining in Burgundy is that once-borderline areas have begun to come into their own, while many of the old reliable names are planting new Pinot clones that accumulate less sugar and ripen later. And there are plenty to choose from: Although there are 47 officially allowed Pinot Noir clones, in reality, only a few are widely used. Leading Burgundy grower Louis Latour is also experimenting with massal selection and replanting with cuttings from existing vines as opposed to young, new nursery material in order to identify those clones best suited for the current environment.

Latour may be a household name, a newer generation of lesser Beaune winemakers are also actively looking for a silver lining in the cloud of global warming. A nationwide program launched in 2018 by the INAO allows wine regions to explore varieties (both white and red) that can cope with the changing climate, and in Beaune, neglected grapes like Aubin, Roublot, Sacy, Melon, César and Tressot are being considered, and many of them are already planted in small pockets throughout the region. Says Latour’s Christophe Deola, “Many of these old varieties were abandoned not from quality, but because they had too much difficulty ripening under past conditions.”

For a wine visionary, the time—as well as the grapes—may be ripe.

The offered 7-bottle package is comprised of one of each of the following wines at $378.

Pernand-Vergelesses – A Mingling of Earth and Red Berries

Vergelesses is a respected lieu-dit just south of Pernand, and in the tradition of the Côte d’Or, the village of Pernand usurped name of its most famous vineyard and tacked it onto its own. The vines, many at ideal elevations, lie adjacent to the red wine Grand Cru of Corton, but Pernand is located on the western side of the Corton hill where the terroir in general is better suited to Chardonnay. Still, the hillside contains microclimates where Pinot Noir thrives.

On the lower slopes, clay soils mixed with flinty residues are rich in potassium and phosphoric acid, while mid-slope, the pebbly limestone soils is ideal for Pinot Noir. The historical issue has been ripening this finicky grape and reds from the appellation have often seemed green compared with those of nearby Pommard and Volnay.

This is an area primed for a few degrees of warming, and recent hot summers have allowed some previously forgettable Pinot Noirs to lose the green edge. In fact, Pernand-Vergelesses underwent vineyard classification in 2001, much more recently than neighboring communes, and just under half the sites were rated Premier Cru, which were then subdivided into eight climats.

Domaine Mongeard-Mugneret

The name ‘Mongeard’ first makes an appearance in Burgundy in 1786, where records show a Mongeard working as vigneron for Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. Skip forward to 1945, when at the age of 16, Jean Mongeard (whose mother was from Famille Mugneret) made wine which he sold by the barrel to négociants. The entire 1945 crop was purchased by Baron le Roy, Marquis D’Angerville, and Henri Gouges, who suggested that the young Mongeard start bottling the wines himself.

In 1975, Jean’s son Vincent began working alongside his father and became responsible for viticulture and vinification of the domaine’s wines. He persuaded his father to return to the traditional method of filtering only in certain vintages. Upon his retirement in 1995, Vincent assumed complete leadership of the domain, which now covers more than 75 acres split among 35 appellations.

Domaine Mongeard-Mugneret, 2019 Pernand-Vergelesses Premier Cru Les Vergelesses ($85)

Domaine Mongeard-Mugneret, 2019 Pernand-Vergelesses Premier Cru Les Vergelesses ($85)

The name ‘Les Vergelesses’ refers to the lieu-dit’s long shapes, stemming the word ‘verge’, or rod. It’s an old agrarian measure equaling a quarter acre. With vines averaging 50 years old, Mongeard draws from just under two acres of the parcel, destemming the bunches, presses and ferments, then matures the wine in 30% new oak. As befits the source, it is fatter and more concentrated than Mongeard-Mugneret’s Village-level wine, and the purple-blue tint expresses raspberries, cherry cola, violets and blackcurrant leading to fleshy and nicely acidic finish.

Savigny-lès-Beaune – Beaune- and Vosne-Romanée-like Duality, With an Earthy Goût-de-Terroir

Chances are, you love wines from the Rhine and are passionate about wines from the Rhône, but at first glance, ‘wines of the Rhoin’ may look like a typo. In fact, this small river flows from the cliffs of Bouilland through the commune of Savigny-lès-Beaune, and alluvia from the overflow adds fertility to the lower slopes of the hills of Beaune. With nearly nine hundred acres of vineyard, the appellation is one of Burgundy’s largest.

Savigny’s terroir features a gentle gradient that becomes steeper as the altitudes approach 1300 feet, where the geology is similar to that of the great Grand Cru hill of Corton. Favored exposures face the south, where the soils are gravelly and scattered with oolitic ironstone. Near the river valley, the red-brown limestone becomes more clayey and pebbly, while the east-facing slopes consist of sand and limestone.

As rich in history as it is in Premier Cru vineyards (there are 22), Savigny-lès-Beaune was once a social hub where the nobility and clergy rubbed shoulders, and the near mythical regard for the quality of its wine is reflected in a stone carving on a Savigny château: “The wines of Savigny are nourishing, theological and keep death at bay.”

Domaine Vincent Ledy

Eight years of wine school may make you think of a professional student, but Vincent Ledy took all that accumulated scholastics and applied it to one of the smallest domains in Nuits-Saint-Georges. Scarcely five acres in total, he produces six labels for a total of 8,500 bottles.

“My first vintage was 2007”, he says. “All I had was a red Hautes-Côtes de Nuits. In 2008, I increased the size of the domain a little bit when I found a very small plot for Bourgogne rouge, less than a quarter acre just opposite of Clos de Vougeot on the other side of the Beaune-Dijon road. The soil is deep clay that is reflected in the character of the wine; blackcurrant is the dominating flavor, the same every vintage. Compared with the Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits it is very different. The Hautes-Côtes is more about cherry flavors. The maximum yield for the regional appellations is 58 hl/ha, but the yield for my Bourgogne rouge is 50 hl/ha.”

Domaine Vincent Ledy ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2018 Savigny-lès-Beaune ($53)

Domaine Vincent Ledy ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2018 Savigny-lès-Beaune ($53)

From the Villages-level lieux-dits Connardises and Aux Liards, the wine shows vivid ruby colors with garnet red tints. Violet, sweet pepper and hints of toast on the nose, followed by a silken palate and red fruit notes including cloudberry and ripe cherry.

Chorey-lès-Beaune – Pleasant, Once Were Labeled Aloxe-Corton

Chorey-lès-Beaune has an interesting dilemma: Rich neighbors. Immediately to the east, the appellation abuts Aloxe-Corton, and for many years, Chorey wines were labeled under the more prestigious Aloxe name, but in 1970, they were granted their own appellation when it was determined that Chorey’s terroir—limestone-marl alluvium over stony subsoil—warrants its own slice of recognition. Almost exclusively planted to Pinot Noir, the vineyards of Chorey have deeper beds of calcium-rich gravel near Aloxe, while toward Savigny are beds of clay with pebbly limestone.

Otherwise, Chorey is effectively a suburb of Beaune, without much picturesque glamour to attract attention from the press. It is pancake flat and without Premier Cru sites; Nathalie Tollot Chorey-based Domaine Tollot-Beaut says, “Our colleagues from other villages often joke ‘Oh, you are on the plain’s side of the highway.”

Domaine Vincent Ledy, 2018 Chorey-lès-Beaune ‘Les Beaumonts’ ($49)

Domaine Vincent Ledy, 2018 Chorey-lès-Beaune ‘Les Beaumonts’ ($49)

‘Les Beaumont’ is considered one of the best climats within Chorey-lès-Beaune, located in the westernmost section near Savigny. The wine shows floral-tinged flavors of cherries, slightly stewed plum braced by cloves and sweet spice.

Monthélie – Full, Rich Volnay-like

Author Pierre Poupon describes Monthélie as being, “…prettily nestled into the curve of the hillside like the head of Saint John against the shoulder of Jesus. Monthélie resembles a village in Tuscany.”

The appellation is home to 15 Premier Cru climat concentrated in one area to the east of the village, bordering the more prestigious vineyards of Volnay. A rose is a rose, but not all Premier Cru sites are created equal, and traditionally, those of Monthélie are not considered among Burgundy’s finest. Classic Monthélie wines are similar to those of neighboring Volnay (the villages are only a mile apart) but are not quite as full flavored or elegant, but they are generally considered to be superior to the red wines of Auxey-Duresses, also just a mile away in the other direction. Again, these are ideal terroirs to stir in a little extra warmth and innovation and follow the improvements with a corkscrew and glass.

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret

The triumvirate of names each has its own special significance to the estate. Named first for the 300-year-old Southern Burgundy village in which it is located, Monthelie Douhairet was run by the Douhairet family for many years. In the early 1970s, the two sisters Armande and Charlotte Douhairet inherited the vines and decided to separate; Armande fought to keep her share while Charlotte sold hers. Then, in 1989, Madame Douhairet asked renowned winemaker André Porcheret to take charge and subsequently, added his name to the domain.

André Porcheret has been one of the great figures in Beaune; prior to overseeing Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet he was the cellar manager at the Hospices de Beaune, then worked for Lalou Bize Leroy to make wines at the newly created Domaine Leroy—whereupon, he returned to the Hospices de Beaune for another five year stint. Today, with his granddaughter Cataldina Lippo, he produces wines on M-D-P’s fifteen acres that are classic, elegant and true to the terroirs of Pommard, Volnay, Meursault and Monthélie.

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret ‘Cuvée Miss Armande’, 2019 Monthélie ($43)

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret ‘Cuvée Miss Armande’, 2019 Monthélie ($43)

Armande Douhairet, known universally as ‘Miss Armande’ passed away in 2004, and to her memory, this cuvée is dedicated. The elevation of the vineyards is obvious in the brightness of the red fruit, evoking pie cherries, orange rind and raw cocoa. The texture is satiny and succulent, with a core of richness framed by lively acids and powdery tannins.

Saint-Romain – Glimpses of The Suaveness of Volnay and The Punch of Corton

Saint-Romain is a village of 200 inhabitants nestling within a valley behind Auxey-Duresses and surrounded by steep cliffs. Neither the population nor the wine trade ever really recovered from the phylloxera blight of the 19th century, and today, only about 7% of the land is under vine. Like Chorey-lès-Beaune, Saint-Romain has no Grand or Premier Cru sites.

The village is divided in two parts, Saint-Romain-le-Haut and Saint-Romain-le-Bas, one on top of the cliffs and one below, with the bulk of the vineyards in the lower section. It is, nonetheless, a geologist’s Valhalla. Saint-Romain sits on the lias (the earliest period of the Jurassic) and the blend of limestones and marls includes patches of clay. The vines face south/southeast and north/northeast at altitudes varying from 900 to nearly 1300 feet.

Domaine Alain Gras

Established in 1979, Alain Gras refers to his domain as ‘young’, and considering that Saint-Romain has been occupied for 6000 years, there may be truth to that. His vines spread over 30 acres in Saint-Romain, Meursault, and Auxey-Duresses.

Gras has found himself as a true ambassador of the Saint-Romain appellation. From a lineage of Burgundy vignerons that dates back five generations, he settled in Saint-Romain with his wife Nathalie and from the outset, their firm mission was to promote the appellation’s value. Joined by his son Arthur, Gras has advanced that value by his passion for rational viticulture and traditional vinification.

Domaine Alain Gras, 2019 Saint-Romain ($54)

Domaine Alain Gras, 2019 Saint-Romain ($54)

Pure Pinot, from vines averaging 35 years old. The bunches are 100% de-stemmed, fermented on the skins for 12 to 15 days with daily pump-overs, then aged in 15% new oak for 12 months. The wine shows black-cherry on the nose with notes of licorice and cinnamon in the background. Unpretentious wine with a bright floral finish.

Auxey-Duresses – The Best Were Sold as Volnay or Pommard

Orientation saves Auxey-Duresses from the ranks of the ordinary. Surrounded by the hills of Mont Melian, Montagne du Bourdon and Montagne du Tillet, Auxey-Duresses is stretched out along the Beaune-Autun road between Monthélie and Saint-Romain, and the hillsides face south and southeast. This geological quirk, along with the limestone content of the soil, has led to nine designated Premier Cru climats, all located on the south-facing Montagne de Bourdon hillside just behind the commune, and some excellent Village-level wines. In fact, a significant proportion Auxey-Duresses’ production is sold under the Côte de Beaune-Villages appellation, but with rising temperatures and an increasing interest in Burgundy’s backcountry wines, the value of the commune appellation is increasing year after year.

Domaine Raymond Dupont-Fahn

Raymond Dupont-Fahn is a fifth generation wine maker and began working in the family business as a child. After earning a Bac d’Oenologie diploma, he took over 12 acres of vines from his father, including plots in Meursault, Puligny-Montrachet and Auxey-Duresses. The domain is located in the village of Tailly in Meursault. As a winemaker, Raymond has cut down on the use of new oak from the 40% used by his father to just 10%, with barrels that are no older than three years. He uses no pesticides in the vineyards, aiming to be as sustainable as he can, and harvests slightly earlier than his neighbors to produce wines with better acidity and lower alcohol.

Domaine Raymond Dupont-Fahn, 2019 Auxey-Duresses ‘Derrière le Four’ ($50)

Domaine Raymond Dupont-Fahn, 2019 Auxey-Duresses ‘Derrière le Four’ ($50)

Meaning ‘behind the oven’, the wine is silky on the palate, with a fine texture entwining around a core of cherries, peonies and a hint of licorice.

Santenay – The Soul of Volnay and The Body of Pommard, No Longer Rough-hewn

Santenay is the most southerly wine-producing commune of the Côte de Beaune, and as might be expected, most of the output is red. The wines are frequently called ‘rustic’ rather than ‘elegant’ and as such, have not yet captured the imagination inherent in the poetry of Pinot Noir; Santenay is said to have the soul of Volnay and the body of Pommard. To those who love such earthy, complex Burgundies, it is well worthy of discovery.

Santenay soils contain less limestone than its northerly neighbors, and more marlstone, but proportions vary based on where the vineyard is located—grey limestone can be found up to a height of 1700 feet, while at one thousand feet, oolitic limestone lies over a layer of marl. The ideal exposure for the vineyards is east to southeast.

Domaine Bachey-Legros

Domaine Bachey-Legros attributes its vinous success to low-yielding old vines with deeply-anchored roots and concentrated juice in the grapes. “Power is matched with elegance and the voice of their terroir is loud and clear,” says Bachey-Legros owner Christiane Legros. “Balance is the key.”

The estate includes sites in Santenay, Chassagne-Montrachet, and ‘Les Maranges’ where the vines were planted between 1935 and 1955 and carefully tended by successive generations. Christiane today operates the estate with her sons Lénaïc and Samuel.

Samuel speaks further on the magic of older fruit: “Gentle extraction is de rigueur, of course, otherwise the tannins in the naturally powerful fruit is overwhelming. An old vine must be constantly monitored and maintained, nurtured and supported. Compared to a young and vigorous vine that needs keeping under control, an old vine gracefully produces berries of extraordinary concentration, imbued with the ‘goût du terroir’ which its roots have extracted from the very depths of the soil. The fruit is itself small, rich in sugars and highly concentrated.”

Domaine Bachey-Legros ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2018 Santenay Les Champs Claudes ($44)

Domaine Bachey-Legros ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2018 Santenay Les Champs Claudes ($44)

Les Champs Claudes is a fine lieu-dit located in Remigny at the northernmost end of Santenay, and according to Samuel Legros, this wine represents an archetypal Santenay. It is toasty with oak and glossy with rich cherry notes and a slight acidic crunch alongside lovely spice notes and meltingly smooth tannins.

Vintage Journal

2019 – Ripe, Concentrated, Tremendous Balance, and Very Approachable

The winter was extremely mild but moved into a chilly spring, with April seeing biting frosts that cut yields. Flowering was uneven due to a cooler than average June and some bunches suffered from millerandage, further cutting yields. Temperatures warmed up rapidly, and by July and August, many of the vines were suffering from heat and drought stress. The summer of 2019 has shown climate change at its most aggressive and much of the crop was lost due to vines either being too stressed or the grapes being sunburnt. The berries that did survive were generally richly concentrated, produced a small but excellent harvest.

2018 – Fresh with Immediate Appeal; Success in Lesser-Known Appellations

This is one of the rare vintages that offers both quality and quantity. On the face of it, 2018 was relatively straightforward; a wet winter and spring topped up the water reserves and the warm, sunny summer ensured the grapes reached ripeness without difficulty. The usual threats of disease, rot, frost and hail were minimal, and harvest took place under blue skies in 86-degree heat. However, the exceptionally warm and dry conditions posed a new challenge for vignerons, with the need to pick early enough to preserve acidity rather than the more familiar wait for ripeness to arrive. In the cellar, handling warm fruit with higher levels of sugar and lower acidity was another test for the region’s winemakers, the most diligent pulled it off beautifully.

- - -

Posted on 2022.07.25 in Pernand-Vergelesses, Côte de Beaune, Savigny-lès-Beaune, Chorey-lès-Beaune, Monthélie, Auxey-Duresses, Côte Chalonnaise, Saint-Romain, Bouzeron, Rully, Côte de Nuits, Côte de Beaune, France, Burgundy, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

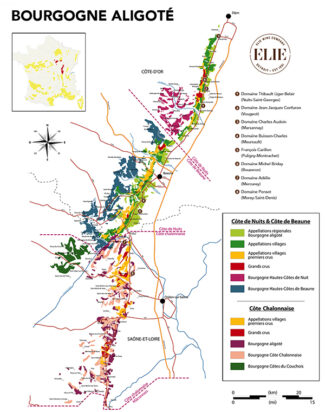

Aligoté, Burgundy’s Other White Grape, Makes Its Case. A Selection From Eight Dedicated ‘Aligoteurs’, Produced in Chardonnay’s Heartland. (7-Bottle Pack $226)

Burgundy is so closely associated with two grape varities—Chardonnay for whites and Pinot Noir for reds—that any other ingredient on the FDA label looks jarring; possibly a typo. In fact, although 80% of Burgundy is planted to Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, the inclusive appellation ‘Bourgogne’ is also an occasional showcase for Gamay and Aligoté.

Bourgogne Aligoté is an AOP Régionale and Aligoté, like Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Gamay, can also be used in the production of Crémant de Bourgogne.

This package represents several different incarnation of 100% Aligoté wine from several respected producers with whom we’ve had reliable and consistent results across the wine spectrum. The older vintages have been kept at optimal conditions and will demonstrate the amazing ability of well-made and properly-curated Aligoté to mature and evolve.

Burgundy’s Aligoté: A New Prospective

“Aligoté!” sounds like a cry of triumph; something you’d shout after making a goal in the World Cup. In fact, perennially overshadowed by its sexier cousin Chardonnay and even its half-sister Pinot Gris (they share a father, Pinot Noir), there was a time when the opposite was true:

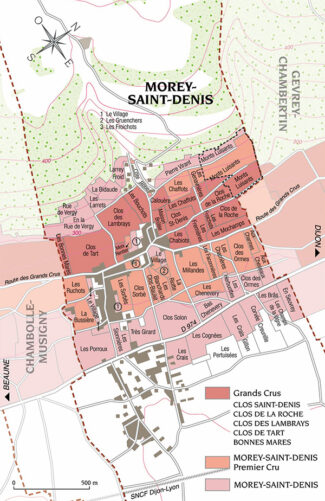

“Before phylloxera,” says Jérôme Castagnier, proprietor of Domaine Castagnier in Morey-Saint-Denis, “Aligoté was planted everywhere, literally. But after the outbreak abated, thanks primarily to American root stock, French growers took stock and realized that Chardonnay and Pinot Noir commanded higher market prices, so that’s what was re-planted. In fact, in some regions, Aligoté was banned altogether.”

Post-phylloxera Aligoté exists under the basic Bourgogne Aligoté appellation established in 1937 and, for the most part, produces inexpensive and simple wines, especially when planted in the less-valued soils of the Saône Valley flatlands. But true Aligoté fans, including Les Aligoteurs (a group of French producers and wine lovers who promote Burgundy’s all-but-forgotten white grape variety) believe that the grape better expresses the terroir of thinner, rockier, hillside soils. A cross between Pinot Noir and the ancient white varietal Gouais Blanc, Aligoté’s profile includes descriptors ranging from fruit-driven and floral to herbal and sharp with acidity. In either case, it is the essential base for the classic cocktail Kir when blended with Cassis.

The grape is on full display in Bouzeron in the Côte Chalonnaise, which is a region that draws more interest from America than it does in its native France. Pockets of Aligoté exist throughout Burgundy, often on the fringes of the priciest real estate. It often presents itself as an ‘every day’ wine, and let’s raise a toast to that, since we have more ‘every’ days than we do special occasions. “Aligoté!”

The offered 7-bottle package is comprised of one of each of the following wines at $226.

Côte de Nuits: A Few Remaining Enclaves

Any white wine from the Côte de Nuits is a bit of an outlier; the region, stretching north to south for a mere twelve miles and in places scarcely 700 feet wide, is noted for its plethora of Grand Cru, Pinot Noir-based reds. It is rightly thought of as the Champs-Elysées of Burgundy, with the output of winemaking being remarkably small compared to much of France: The average domain releases fewer than 1000 cases per year.

99% of Côte de Nuits’ vineyards are planted to Pinot Noir, and the few remaining enclaves of Aligoté make up around one-tenth of a percent. As such, remarkable for their rarity, it can generally be assumed that they are of exceptional quality.

Domaine Thibault Liger-Belair (Nuits-Saint-Georges)

Winemaking has been the legacy of Liger-Belair family for a quarter of a millennium. Prior to establishing his own domain, Domaine Thibault Liger-Belair studied oenology, worked for a communications firm in Paris and started an internet company to discover and sell high quality wines. Still, the vines beckoned, and in 2001, at the age of 26, he returned to them. The following year saw his first harvest of Nuits-Saint-Georges, and in 2003, he expanded into Richebourg Grand Cru, Clos Vougeot Grand Cru and Vosne-Romanée Premier Cru Petits Monts and in 2004, he discovered biodynamics, a train on which he has been a front-row passenger ever since:

“I saw a change in my vineyard, which went from gray soils to brown/red and then sometimes to black.” Still, his overarching philosophy is that each vineyard needs something different: “I don’t like 100% of anything: new barrels, whole clusters. My job is to decide which grapes we have and then decide a viticulture and winemaking approach.”

In 2018, he made wine from 23 different appellations and purchased grapes from a ten more, but did the work there. “We don’t purchase grapes where we don’t do the work,” he says.

Domaine Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Clos des Perrières La Combe’, 2019 Bourgogne-Aligoté ($44)

Domaine Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Clos des Perrières La Combe’, 2019 Bourgogne-Aligoté ($44)

Located in an old quarry bordering the Village appellation Nuits-Saint-Georges Les Argilats (Vosne-Romanée side), the Aligoté grown in the climat ‘Clos des Perrières La Combe’’ sees six days of skin contact before a slow, seven-hour press. Vinification takes place in neutral barrels and produces an Aligoté replete with gorgeous texture and a ripe bouquet of orchard fruits in front of the grape’s signature minerality, which often comes across as saltiness.

Domaine Jean-Jacques Confuron (Vougeot)

The 20 acres that make up Domaine Jean-Jacques Confuron are now controlled by Sophie Meunier-Confuron and her husband Alain Meunier, who converted all parcels to organic viticulture in 1990. This includes excellent parcels of Premier Cru and Village vines in Vosne-Romanée, Chambolle-Musigny and Nuits-Saint-Georges as well as two great Grand Crus, Romanée-Saint-Vivant and Clos Vougeot.

The Confurons vinify according to the Burgundian mantra of ‘power without weight’, seeking a depth of flavor balanced by refinement and elegance. ‘Aux Plantes’ is a lieu-dit situated on clay-limestone soils that are ideally suited to Aligoté.

Domaine Jean-Jacques Confuron ‘Aux Plantes’, 2019 Bourgogne-Aligoté ($37)

Domaine Jean-Jacques Confuron ‘Aux Plantes’, 2019 Bourgogne-Aligoté ($37)

In order to preserve the freshness and tension inherent in the variety, the Aligoté used in the climat-specific wine from old vines lying on slopes with clay-calcareous soils. They are vinified in stainless steel vats and aged on lees without ever seeing oak. The wine shows a citrus basket of flavors along with notes of pear, green apple and hints of white flowers and raw honey.

Domaine Charles Audoin (Marsannay)

Charles Audoin was a true Burgundian visionary: He purchased premium land in Marsannay before it was even an appellation. Along with his enologist wife Marie-Françoise, he founded the domain in Marsannay-la-Côte in 1972, when it was a mere six acres planted chiefly to Gamay and Aligoté. In time, he expanded the holdings to cover 35 acres. His son Cyril is the fifth generation to join the family business, and continues his parents’ commitment to wines drawn primarily from single vineyards; his wines well-structured and wonderfully pronounced minerality and he believes that the estate offers among the best value in in the Côte de Nuits.

“I think it will be more difficult to change the image of Marsannay within Burgundy than internationally,” he says. “One problem is that Marsannay has been known since the 1930s for its rosé. That is part of the reason why Marsannay didn’t obtain its village appellation when the other villages did; when you are producing rosé you are not considered to be as serious as when you produce red or white. But rosé is part of our history, and ironically, the world today is producing more and more rosé while here in Marsannay, we are making less and less.”

Domaine Charles Audoin, 2020 Bourgogne-Aligoté ($27)

Domaine Charles Audoin, 2020 Bourgogne-Aligoté ($27)

From organic 90-year-old vines which impart rich blend of scents, both floral and fruity—acacia blossoms and nectarine. The grapes undergo a cold soak prior to fermentation and are then transferred to neutral oak barrels. The mineral-driven palate echoes the aromatics, with peach and apple displaying bright acidity tempered by creaminess from the oak.

Côte de Beaune: Terroir For Red And White

Named after its principle town Beaune, the Côte de Beaune is Burgundy’s white wine powerhouse, with some of the world’s most expensive Chardonnay-based wines produced within its borders— a mere 16 miles from top to bottom. Most of these have ‘Montrachet’ attached to the names, in homage (and with financial savvy) to the region’s leading vineyard. But red wines also play a significant role in the region’s fame, particularly those from the Premier Cru vineyards of Pommard and the Grand Cru Corton.