Making Sense of Burgundy’s Côte de Nuits: End to End, Spanning Six Communes in Two-Dozen Parcels by Brothers Vincent and Philippe at Domaine Lécheneaut

‘Côte de Nuits’ is a name that excites the senses; it is mysterious (the name means ‘hills of the night’), it is sensuous (95% of its output is built around silk-smooth, hedonistic Pinot Noir) and it is evocative, with wine aromas frequently liked to roses and the spice-box. Hold a bottle of Côte de Nuits in your hands and you hold a key to a kingdom which produces the finest Pinot Noirs in the world. But the grape itself is a mystery within a mystery, and making sense of the individual styles and terroirs of the revered red wine vineyards of Côte de Nuits’ cannot be accomplished with a single bottle. Every village has its story and every vineyard its history; the wines vary by texture, color and dominant flavor notes.

As a primer to help isolate some of these characteristics, we have picked a top producer with small parcels in six of the most significant Côte-de-Nuits communes. It’s meant to be a general overview of the Côte de Nuits, but the heady sumptuousness of these wines is anything but generic.

The Notion of Terroir

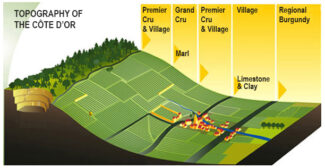

The terroir of Côte de Nuits is built upon a pixel-like plan of vineyards that seems more like a maze than a map. Exposure is vital, and it’s said (tongue-in-cheek) that all the Grand Crus face Germany. The truth is, most of Burgundy is marginal grape country, and the farther north you go, the tougher it gets. But given the opposite conditions—compost-rich soil, plenty of sunshine and a long growing season with copious rainfall—you end up with happy vines that do not produce particularly complex wines. The stony soils of the Côte de Nuits’ Grand Crus excel chiefly because they are poor; the limestone bedrock offers abundant levels of elemental calcium, which helps open up the capillaries in the soil, increasing porosity and assisting root colonization. Stone fragments add to the drainage capability of the soil and reciprocally, these same fragments are a supplemental source of water that the roots can draw upon during times of shortage. Both water stress and water surplus can delay the onset of grape maturation, and the Grand Crus’ load of small, porous stones helps buffer the vine against both eventualities, favoring the early maturation of small-berried bunches. This unique set of conditions, when paired with the ideal elevation and topography, promotes maturity while beneficially increasing the ratio of skins to juice.

The Burgundian Landscape

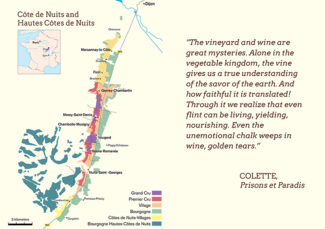

The Côte de Nuits is the northern half of the escarpment of the Côte d’Or and is named after its principal town of Nuits-St-Georges. The most basic wines, produced mainly from grapes grown on the lower slopes of the escarpment, are labeled with a generic appellation such as Bourgogne Passtoutgrains (in which Pinot Noir may be legally blended with Gamay) or simply, Bourgogne.

The regional appellation of Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits produces marginally superior reds from the higher slopes. A notch above these are the communal wines labeled Côtes de Nuits-Villages, produced in the smaller villages of Fixin, Brochon, Prémeaux, Comblanchien, and Corgoloin and the more prestigious village wines, which carry as their appellation the name of the village in which they were made. The principal villages of the Côte de Nuits, from north to south, are Marsannay, Fixin, Gevrey-Chambertin, Morey-St-Denis, Chambolle-Musigny, Vougeot, Vosne-Romanée, Flagey-Échezeaux, and Nuits-St-Georges.

Vintage 2018: Fresh with Immediate Appeal

On the face of it, 2018 was straightforward and sublime; a wet winter and spring topped up the water reserves and a warm, sunny summer ensured the grapes reached phenolic ripeness without difficulty. The usual threats of disease, rot, frost and hail barely entered the picture, and harvest took place under blue skies inclement weather.

Two hailstorms in the southern part of Nuits-St Georges reduced crop, but for the most part, 2018 was an outstanding vintage that produced both early drinking examples and wines that will improve substantially with age.

Domaine Lécheneaut

Burgundian Sensibility

Having been founded in the 1950s by Fernand Lécheneaut, the domain launched modestly, with five acres of vineyard in Nuits-Saint-Georges, Chambolle-Musigny and Morey-Saint-Denis. During these early years, Lécheneaut sold bulk wine to négociants, but in 1985, his sons Philippe and Vincent took over and brought with them an expanded vision. They grew their vineyard holdings while they began to bottle at the estate. The new Lécheneaut plots, including several Premier Cru vineyards in Chambolle-Musigny and Gevrey-Chambertin, speckle the map of the Côte de Nuits from north to south, but judiciously—many of the holdings are under an acre. With vines in 23 appellations, the total land under their management is around thirty acres.

The Brothers Vincent and Philippe Lécheneaut

As the Lécheneaut brothers approach retirement, Vincent’s son Jules has joined the team with a view toward combining lessons learned in his experiences working vines in Oregon with the exceptional terroir his family nurtures.

The Burgundian Sensibility in the Vineyard – The essence of the terroir philosophy is that a given wine should demonstrate—through its weight, smell, taste and nuance—its place of birth. Failing to prepare for this goal even before the first root stock goes into the ground can compromise the results years down the line. In the vineyard, Burgundian sensibility is a practice that involves ecology, and soil—however vital—is only one part of that. Of equal importance is a thorough understanding of the site, and which clone will best mirror the available orientation, the local topography and the climate. Burgundian sensibility also extends to yields, which must be contained and limited to best reflect the characteristics of the grape. Above all, perhaps, is the sensibility born of experience in knowing when to pick; grapes at less than optimal ripeness make ‘green’ wines, but those sudden onslaught of rain that Burgundy is heir to may ruin the harvest of growers who chose to wait a single day too long. Ultimately, soil is destiny, and how the trace elements it contains translate into the glass are all part of man’s endless attempts to improve upon, while working in harmony with, nature.

The Burgundian Sensibility in the Winery – Once picked and delivered to the winery, a whole new stratum of sensibility develops. To stem or not to stem becomes a primary question; stems contain more tannin than grapes, and although tannin is frequently mentioned in gushing descriptions, too much results in an astringent mouthful and too little produces a wine than tastes thin and (since tannin is also a preservative) may not age long enough to reach its potential. Decisions on fermentation techniques now weigh in—whether to use commercial yeast or ambient, naturally occurring yeast fuels many a cellar debate. Either way, once fermentation has begun, it must be controlled, and in Burgundy—the home of high tech and low labor—it may be done by hand, with human beings immersing themselves in vats that have grown too cool for vigorous fermentation. Alternately, excessive heat—self-generated as a byproduct of fermentation, is of particular danger to delicate Pinot Noir. One technique to counteract heat is to add whole bunches of uncrushed grapes which have a cooling effect. You will see ‘whole bunch’ or ‘partial whole bunch’ on technical notes for precisely this reason.

Hautes-Côtes de Nuits: Firm & Straightforward, Middle-of-the-Road Temperament

Due west of Nuits-Saint-Georges, along southern half of a 12 mile stretch of vineland known as the ‘Champs-Élysées of the Bourgogne’, lies a lesser known wine region that is ripe for discovery. Once neglected by both growers and patrons, the area known as Hautes-Côtes de Nuits has enjoyed a viticultural renaissance in the past decade that has manifested terroirs similar to those in the heralded Côtes itself.

Overlooking the slopes of Gevrey-Chambertin and extending as far as the wood of Corton, the appellation was officially recognized in 1961 and covers 20 communes; 16 in the Hautes Côtes region in the département of Côte-d’Or, plus the higher areas of 4 communes in the Côte de Nuits where elevations average 1200 feet. Vines are planted alongsides of valleys that cut through the Jurassic limestone plateau to the west of the Côte; the underlying rock is the same as that of the Côte but the soil is thin or non-existent, formed by a mixture of eroded limestone and marly subsoil.

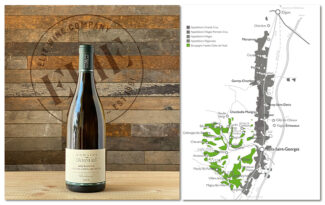

Domaine Lécheneaut, 2018 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits ‘Chardonnay’ ($48)

Situated on a hillside facing south at about 1150 feet, the vines cover the sloping valley cutting through the Jurassic chalky plateau, west of the Côte, a substrate is identical to that of the vine covered hillside, but the surface formations are very thin, at times non-existent. The chalky-clay soils are a result of the alteration of the limestone and marls substrate and are ideal for Chardonnay. The wine shows hawthorn and honeysuckle on the nose, which mingles on the palate with buttery apple, lemon, and hazelnut. Vines average 25 years old; 2100 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

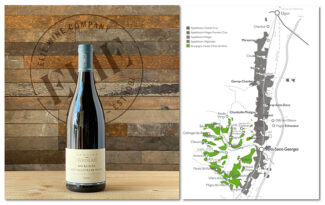

Domaine Lécheneaut, 2018 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Nuits ($48)

From a two-acre plot on the same Jurassic chalk plateau, from vines with an average age of 63 years. The wine is beautifully balanced, with aromas of raspberry, black cherry and licorice. Direct and firm flavors with granular, but well-integrated tannins. 7500 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

Marsannay: Smooth & Generous, a Meaty Wine

Referred to as the ‘Golden Gate to the Côte de Nuits’, Marsannay produces wine in all three chromatic styles—red, white and rosé—but the reds, in particular, are heralded for their richness, resembling in style the wines of neighbors Fixin and Gevrey-Chambertin. As an appellation, Marsannay encompasses the communes of Chenôve, Marsannay-la-Côte and Couchey.

The best vines are planted mid-slope with easterly or southerly exposures, and have historically been considered of only modest quality, with no Premier Cru—and certainly no Grand Cru—sites. However this issue has been under review in recent years, and two neighboring sites, Clos du Roy and Les Longeroies, gained Marsannay Premier Cru status in 2020.

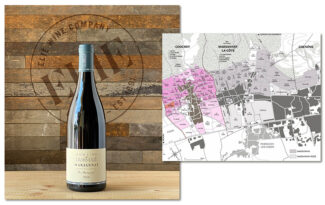

Domaine Lécheneaut, 2018 Marsannay ‘Les Sampagny’ ($77)

‘Les Sampagny’ is a lieu-dit in the Couchey commune just north of Fixin and south of Marsannay; the soils are limestone and marl and the vines’ average age is 40 years. They produce a fruit-forward, openly-knit wine filled with crisp cherry, pie spice and a long, mineral-driven finish. 1500 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

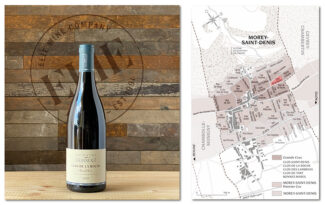

Morey-Saint-Denis: Full & Powerful, Sings Tenor

Forming a stylistic bridge between the firm, fleshy wines of Gevrey-Chambertin and the perfumed wines of Chambolle-Musigny, Morey-Saint-Denis is a wealth of Crus, including twenty Premier Crus and five Grand Crus: Clos de Tart, Bonnes Mares, Clos de la Roche, Clos Saint-Denis and Clos des Lambrays. The best sites are planted on thin, well-drained, oolitic limestone soils that date from the Middle Jurassic, and occupy the middle slopes while lesser quality wines are produced on the highest and lowest elevations.

Even among Burgundy enthusiast, the Premier Cru climats are sometimes unfamiliar, due in part to the practice of blending of several vineyards as a generic Morey-Saint-Denis Premier Cru bottling, something that is somewhat more common here than in other communes.

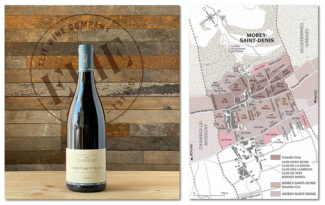

Domaine Lécheneaut, 2018 Morey-Saint-Denis ($123)

A textbook Morey-Saint-Denis blend of parcels from Pierres Virants, En Seuvrey, The Cognées and The Porroux, where the vines are rooted in limestone and chalky-clay soils from the Jurassic period; Bathonien white oolite on the top of the hill and Bajocien chalky eutroques on the downslope. The wine is rich and assertive with Gevrey-Chambertin’s muscle and Chambolle-Musigny’s grace—its tone is suggestive of tart cherries, rose hips, violets and walnuts and fills out with stony persistence. 4200 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

Domaine Lécheneaut, 2018 Clos de la Roche Grand Cru ($475)

From a quarter-acre corner of the famous wall-enclosed ‘Clos de la Roche’ vineyard, where the vines are, on average, 60 years old. The vineyard sits above the Route des Grands Crus at an elevation of around 900 feet and is divided among eight climats. This wine in particular hails from Monts Luisants. De la Roche’s soils are only ten inches deep, but the aromas in the wine are soil-driven with blackcurrant, mocha, cinnamon and cherry throughout with an attractive sweetness and fine-grained tannins to finish. 500 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

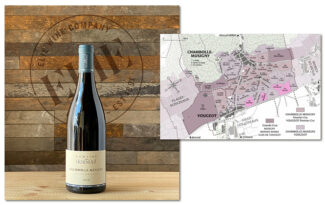

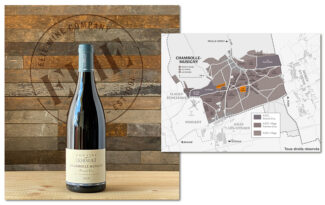

Chambolle-Musigny: Elegant & Subtle, Regarded as ‘Feminine’

Chambolle-Musigny is tiny, but the village itself (with a population of 400 and an almost equal number of acres under cultivation) is in prime Pinot country—on the upper, well-drained mid-slope of the Côte d’Or escarpment at an altitude of around 1000 feet. The vineyards surround the village, stretching eastwards down the slope towards Bourgogne AOP zones and southwards to the edge of the neighboring village of Vougeot. Le Musigny and Les Petits Musigny extend further southwest in a corridor to the Premier Cru La Combe d’Orveau and the border with Flagey-Échezeaux while to the north lies Morey-Saint-Denis.

The output is small but the quality is prodigious; 24 Chambolle-Musigny Premier Cru sites cover 138 acres and two Grand Cru vineyards cover 59 acres.

Domaine Lécheneaut, 2018 Chambolle-Musigny ($123)

From a single acre site of 63-year-old vines across several Villages-level lieux-dits, Chardannes, Herbues, Maladières and Babillère. Most feature thin bedrock soils where cracks in the limestone encourage root exploration, and ensure a marvelous complexity. The bouquet of violets and rose petals introduces a wine which is beginning to age into spicy maturity with prunes and truffles and a palate that has evolved with rich, silken tannins. 2400 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

Domaine Lécheneaut, 2018 Chambolle-Musigny Premier Cru ($211)

A tiny plot (smaller than a quarter-acre) of 70-year-old vines in ‘Les Plantes’ and ‘Les Borniques.’ These lieux-dits are located on the alluvial cone of the Ambin valley and the substratum is composed of Periglacial red silt enriched with breccias of the Bathonian limestone that forms the plateau. Sophisticated and elegant, the wine presents rich aromas of blackberry, blueberry, redcurrant and ripe plum which over time should develop into leather, chocolate and pepper notes. 1000 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

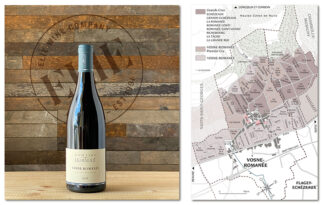

Vosne-Romanée: Full-Bodied & Voluptuous, A Ruben’s Nude

There are few wine communes in the world as hallowed as Vosne-Romanée; the village has been a known source of quality wines since the arrival of the monks of the Saint-Vivant monastery more than a thousand years ago. Today, it makes wine almost exclusively from Pinot Noir, although up to 15 percent of the local white varieties are permitted to allow for natural planting variations and mutations. Originally named just Vosne, the village took the suffix Romanée in 1866 in honor of its most prized vineyard, La Romanée.

Nowhere is terroir more microscopically defined; Vosne-Romanée’s best vineyards lie just above the village on the mid-slope. Around these prestigious Grand Cru sites are dotted the Vosne-Romanée Premier Cru vineyards along with some entirely unclassified land. The difference between a Grand Cru vine and one deemed worthy only of a regional Bourgogne appellation is sometimes a matter of a few feet.

Domaine Lécheneaut, 2018 Vosne-Romanée ($123)

From the lieu-dit Aux Ravioles, located on the bottom of the hill on lightly chalky soils mixed with marl and clay. It is an opulent and fleshy wine with notes of brandy-soaked cherries and vibrant, concentrated raspberries with elegant undertones of earth and graphite. 2400 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

Nuits-Saint-Georges: Muscular & Vigorous, Sturdy Character

With the village of Nuits-St-Georges itself as the fulcrum, the robust appellation extends to the north as far as the border of Vosne-Romanée, while the southern section lies partly in Nuits-Saint-Georges and partly in Prémeaux. The wines from each section are unique in style and according to experts, with differences defined (in the main) by the lay of the land. The soils in the northern sector are built around the pebbly alluvium that washes down from up-slope, or in the low-lying parts, around silty deposits from the river Meuzin. In the southern sector the alluvia at the base of the slopes originate in the combe of Vallerots where there are deep marly-limestone soils, while at the top of the slope, the soil has nearly all eroded away and the rock is near the surface. In both regions, favored exposures are mostly to the east or southeast.

Domaine Lécheneaut, 2018 Nuits-Saint-Georges ($105)

A blend from seven parcels, Damodes, Saint Jacques, Herbues, Tuyaux, Belles Croix, Charmois and Chaliots where terroirs vary with the north-to-south orientation—the soils from the northern parcels contain silt and gravel from the alluvial Meuzin valley and in southern parcels, silts originate from the Combe des Vallerots. Fragrant notes of dried flowers and bright red currant lead to a smooth palate filled with crunchy cherry flavors and a mineral-driven core. 7500 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

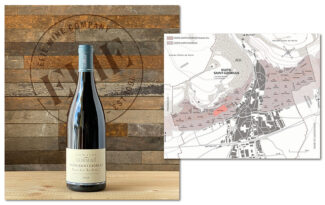

Domaine Lécheneaut ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2018 Nuits-Saint-Georges ‘Au Chouillet’ ($123)

The ‘Au Chouillat’ lieu-dit features 70-year-old vines planted in marl formations covered by clay and red silt deposited from ancient alluvial cones and sediments from the valley of Meuzin—the river that divides the Nuits vineyards into its north and south zones. Hints of creamy oak and forward cherry with undertones of Kirsch and a soft lift of smoke. 4200 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

Domaine Lécheneaut, 2018 Nuits-Saint-Georges Premier Cru – Les Damodes ($176)

‘Les Damodes’ makes reference to the Druidesses who previously inhabited the area. These vines are planted with a southeasterly aspect and at high altitudes bordering Vosne-Romanée. For Domaine Lécheneaut, the lieu-dit represents about an acre’s worth of brown calcareous soils, fine gravel, silty-clay and reddish rubble. A detailed, elegant wine with smoky cherry, lacy spice and herb aromas above licorice and violet. 3000 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

Domaine Lécheneaut, 2018 Nuits-Saint-Georges Premier Cru – Les Pruliers ($176)

‘Les Pruliers’ is located just a few hundred meters to the southwest of the Nuits-Saint-Georges commune. Its relative proximity to the Meuzin River means there is a greater percentage of clay in the soils than in the Premier Cru plots further to the south towards Beaune. Though there is more gravel in the southern part of the plot, overall this gives Les Pruliers wines greater body. The bouquet evokes wild plums as well as notes of licorice and spiced roses, and as the wine matures aromas of cocoa, smoked meat, and undergrowth arise and smooth out the generous structure. 2700 bottles made.

*click on image for more info

- - -

Posted on 2022.09.08 in Chambolle-Musigny, Hautes-Côtes de Nuits, Côte de Nuits, Morey-Saint-Denis, Premeaux-Prissey, Premeaux-Prissey, Nuits-Saint-Georges, Marsannay, Gevrey-Chambertin, France, Burgundy | Read more...

The Champagne Society October 2022 Selection: Champagne Penet-Chardonnet

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet

Grand Cru Verzy Lieu-dit ‘Les Blanches Voies’ Blanc de Blancs 2012, Extra-Brut

Special Price for members of the Champagne Society is $93.

The Evidence Of Things Terroir: In Pursuit Of Place Of Origin Expression And Authenticity In Champagne. Penet-Chardonnet’s Single Grand Cru Villages & Lieux-dits.

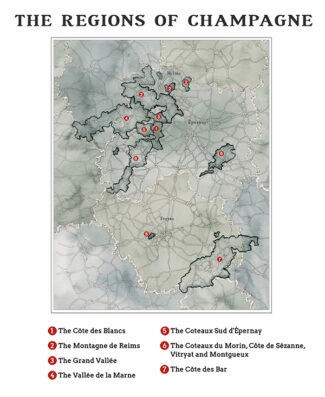

The concept of terroir reigns supreme over the essence of what makes Champagne unique, and much of the discussion—as it is in Chablis, a hundred sixty miles to the south—amounts to chalk talk. Subdivided into seven distinct regions, (The Montagne de Reims, The Grand Vallée, Vallée de la Marne, The Coteaux Sud d’Epernay, The Côte des Blancs, The Coteaux du Morin, Côte de Sézanne, Vitryat & Montgueux and Côte des Bar in the Aube) these areas can be demarcated by subsoil—a subject we’ll dig into deeper. Enough to say that chalk content is a chief difference among them, and in Champagne, the chalk is formed of calcite granules built from the fragile shells of marine micro-organisms. Being highly porous, this sort of base acts as a reservoir that provides the vines with a steady supply of water even in the driest summers—which, in France, are increasingly becoming the rule. Chalk draws water upward through capillary action, and effort required to tap into this supply puts the vines under just enough stress during the growing season to achieve that delicate balance of ripeness, acidity and berry aroma that is the hallmark of all fine Champagne.

(photo: Champagne Henriot)

As an exemplar of terroir in Montagne de Reims, and in particular the two famously picturesque Grand Cru villages of Verzy and Verzenay, this week’s selection features the complex and expressive wine of Champagne Penet-Chardonnet. Alexandre Penet, who took over the estate in 2007, has made his mark on the region quite eloquently; among his representational innovations is his dedication to low dosage wines—all his Champagnes are Extra Brut and some are Brut Nature, with no sugar added at all. Additionally, Penet has approached single vineyard selections as a keystone of his portfolio whereas Champagne producers have tended to favor blends from several villages that supply, of course, a variety of terroirs. The focus on site expression rather than the potential synergy of a cuvée is an approach more associated with still winemakers in France—a point that Penet is happy to underscore with his mission statement: “High-quality champagne is so much more than just the bubbles,” he maintains. “Champagne should be enjoyed in the same way as a still wine.”

Exploring Pinot and Chardonnay Country: The Montagne de Reims

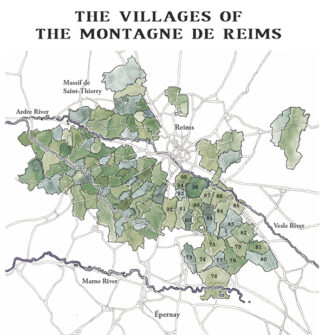

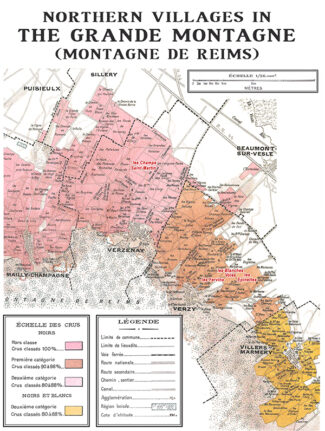

Between the Marne and the Vesle Rivers lies a broad and undulating headland of remarkable forest, including the world’s largest preserve of dwarf beech trees. The region offers a golden opportunity for botanists, and if you happen to be a wino, you’re also in luck: The gold can be found along the slopes of the seventy-million-year-old mountain of Reims. The landmark massif is a cross-section of chalk, sand, clay and limestone, an ideal crucible for Champagne’s trio of grapes, but especially for Pinot Noir: This is the varietal most widely planted throughout the region except in Trépail and Villers-Marmery, where the Chardonnay finds its own marvelous sanctum.

The vineyards of Montagne de Reims lie in the most northerly sector of the Champagne AOP, hugging the western and northern flanks of the mountain in a huge semicircle that extends from Louvois to Villers-Allerand. Vines carpet the limestone slopes and steep valleys and follow the contours of the mountain from Trépail to Villers-Marmer before disappearing into the folds and creases of its northern flank. The vines are planted on its slopes at varying expositions ranging between north-west to south-east, forming an arc that is open to the west. The challenge for growers in this northern outpost is avoid the morning frost and to expose the vines to a full day of sunlight to encourage as much ripening as possible.

The city of Reims is situated on this mountain of chalk and from it, the Romans built cities; the empty limestone quarries they left behind, called ‘Crayères’, provide ideal humidity and steady temperatures for the slowly maturation process required in the acidic wines that this cool northerly region tends to produce. Thus, in the Montagne de Reims, all the Champagne stars have aligned.

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet

“In Pursuit of Rarity, Authenticity and Perfection”

Champagne is the traditional celebratory beverage served at weddings, but was never more appropriate than at the 1967 marriage of Christian Penet to Marie-Louise Chardonnet, joining in matrimony 400 years of wine tradition in Champagne. With this union, the family business expanded to cover fifteen acres of Grand Cru vines—13 in Verzy and two in Verzenay—and thus, before the birth of their son Alexandre, Penet-Chardonnet was born.

As a wine region, Champagne has always had an ambiguous relationship with innovation. On one hand, the process of bottle-fermentation is so established that its name—méthode traditionelle—translates to ‘traditional’. Still, every small grower Champagne wants to increase its exposure to the world’s stage, and to stand out in a field that numbers in the thousands often requires thinking outside the wine crate. Alexandre Penet, who grew up in the cellar watching his grandfather and father make Champagne, made a conscious decision to divert from tradition: He went to college to study engineering and, after qualifying, left Champagne to work overseas in Brazil and in Africa in industries far beyond the winemaking umbrella. In addition, he managed to squeeze in an MBA from the University of Chicago Business School.

Alexandre Penet (photo: Kara Marie Dober)

But the lure of the vine is strong, and so is the family name. By the time Alexandre had succumbed to both, he’d gained enough real-world experience to understand precisely the kind of wine he could—and should—be making. The clarity of his vision required embracing a unique approach to the sublime properties his family owned in order to coax from them the maximum potential. His most novel shifts in the Champagne paradigm are discussed in detail below, but his legacy in Montagne de Reims can be summed up more succinctly:

Alexandre Penet creates wine for true Champagne enthusiasts, in limited releases and with labels explosive with information to appeal to the nerdiest among us—the blend, blending, the duration of aging, the vinification method, the date of bottling, the date of disgorging, the dosage, and in relevant bottles, the date of harvest for a specific plot.

Site-Specific Champagne: Single-Village Crus And ‘Lieux-dits’

Site specificity is the heart and soul of the concept of terroir. Even chefs de cave who blend do so based on characteristics found in the various source wines, and these come from the vine’s location. Still, this is a technique that champions homogeneity—the goal of a House who does not want to advertise the ups and downs of vintages or vineyards, but rather, to produce wine in a consumer pre-approved style. Thus, Champagne cuvées becomes the art of the blender.

Alexandre Penet is from a different school: The art of the earth. Among his baseline commitments when he left bureaucracy for winemaking was that any wine should faithfully reflect its place of origin. With exclusively Grand Cru vineyards from which to draw, of course, he had a considerable head start.

When the lieu-dit concept enters the picture, the view through the microscope narrows. Champagne contains 17 villages that can boast Grand Cru status; this means that 100% of the grapes used in the wine come from a village so named. It’s a concept that originated in 1920 in ‘The Échelle des Crus’ (Ladder of Growth) system and it’s worth noting here that more than half of these Grand Cru villages are in Montagne de Reims. The lieu-dit, or named vineyard system is older—the field name of each lieu-dit has been documented since the creation of the land registry by Napoléon Bonaparte in 1807. In scope, therefore, a lieu-dit covers a narrower, more based upon the reasonable deduction that different bits of given appellation, or cru, perform differently.

Understanding and showcasing these differences is the goal of site-specific wines, and in Champagne, there is no greater advocate for this expression than Alexandre Penet:

“I am a true believer in letting the wines express their origins,” he says. “The winemaker’s purpose being to provide guidance and mentoring rather than imposing his own will on the wine.”

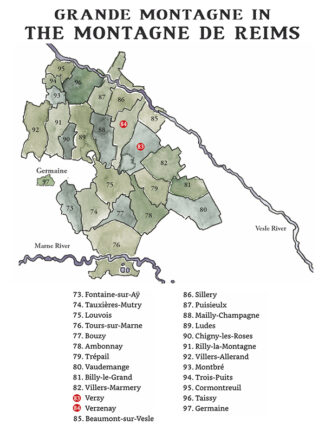

Revealing Grande-Montagne’s Northern-Facing Villages

The Montagne de Reims is many things—it is storied, it is prolific, it is uniquely situated for the production of outstanding wine grapes. One thing it isn’t is monolithic. In fact, it’s not even really a mountain, but a broad plateau, the Grande Montagne, comprised of many hills and valleys encircling Reims. The Grand Crus that host Penet-Chardonnay’s vineyards lie on the northern segment. Along with the villages of Mailly, Beaumont-sur-Vesle, Puisieulx and Sillery, Verzenay and Verzy have mostly north-facing slopes, producing distinctly different wines than those from the south-facing slopes of Ambonnay, Bouzy and Louvois:

Pinot Noir blends from north-facing slopes do not display the same powerful, vinous character as those from south-facing slopes. Freshness and elegance are at the forefront of Pinot’s expression, and thus, there is less need to blend in too much Chardonnay. When slopes face north, the grapes are fairly slow to ripen, and these vines are often the last to be harvested. Even then, they contain high level of acidity and produce in wines that often requires few years to develop their full potential. In general, they tend to showcase the red berry and spice notes and as Grand Cru wines, have all the depth and complexity expected from the top of the pyramid.

I – Verzy: Freshness and Finesse

Consisting mainly of north-facing slopes, Verzy’s thousand acres of vineyards are planted mostly Pinot Noir, with Chardonnay making up 22% and Pinot Meunier 12%, all classified 100% Grand Cru. The north-facing slopes means that Pinot Noir-dominated Champagnes from Verzy tend to be less commanding but more finely nuanced than those that originate from villages with south-facing slopes, such as Aÿ, Ambonnay and Bouzy.

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, Roederer’s chef de cave, explains the differences between Verzy and nearby Verzenay: “The soils of Verzy are much whiter than Verzenay; it’s chalkier the closer yo get to Villers-Marmery. You can see it when you plow—the soil is very fine, very chalky. Across the border in Verzenay, the soils become deeper and heavier, and produce richer wine with less finesse.”

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet, Grand Cru Verzy Lieu-dit ‘Les Blanches Voies’ Blanc de Blancs 2012, Extra-Brut ($110)

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet, Grand Cru Verzy Lieu-dit ‘Les Blanches Voies’ Blanc de Blancs 2012, Extra-Brut ($110)

100% Chardonnay. ‘Les Blanches Voies’ is located in the heart of Verzy; it is north-east oriented with an 8% grade, on soils ideal for the Chardonnay to which it is planted exclusively—the vines are now 27 years old. A rare cuvée, one of the very few Grand Crus made from a single plot and one of the very few Blanc de Blancs Grand Cru Champagnes from Montagne de Reims.

(Bottled May 2013, disgorged April 2021, dosage at 5.2 grams/liter, less than 2000 bottles made.)

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet ‘Prestige Grande Réserve’, Grand Cru Verzy 2008, Extra-Brut ($99)

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet ‘Prestige Grande Réserve’, Grand Cru Verzy 2008, Extra-Brut ($99)

70% Pinot Noir, 30% Chardonnay. The grapes for this exceptional wine originate from the estate’s Verzy properties and were aged on lees from bottling up until its date of disgorgement. Very complex and powerful, it develops aromas of stewed apple, straw and doughy biscuit notes. The palate is edgy with minerality and shows spiced and subtle woody notes.

(Bottled May 2009, disgorged January 2021, dosage at 6 grams/liter, less than 5000 bottles made.)

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet, Grand Cru Verzy Lieu-dit ‘Les Epinettes’ Blanc de Noirs 2010, Extra-Brut ($120)

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet, Grand Cru Verzy Lieu-dit ‘Les Epinettes’ Blanc de Noirs 2010, Extra-Brut ($120)

‘Les Epinettes’ is among the best plots in Verzy; its orientation is northwest at a 3% grade, and is planed exclusively to Pinot Noir vines, now more than 40 years old. Sharp, precise and powerful, it shows peach, apple, nectarine and candied lemon backed by a fine yeasty mousse.

(Bottled May 2011, disgorged January 2021, dosage at 3.6 grams/liter, less than 3000 bottles made.)

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet, Grand Cru Verzy Lieu-dit ‘Les Fervins’ 2009, Extra-Brut ($110)

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet, Grand Cru Verzy Lieu-dit ‘Les Fervins’ 2009, Extra-Brut ($110)

‘Les Fervins’ occupies a prime spot in Verzy on chalky soil with a perfect south-east orientation, atop which sits the cross that is the logo of Penet-Chardonnet. 70% Pinot Noir, 30% Chardonnay, the wine shows focused aromas of apple, caramel and lemon minerals with a hint of iron-rich meatiness along with salt and spice.

(Bottled May 2010, disgorged October 2021, dosage at 4.8 grams/liter, less than 5200 bottles made.)

II – Verzenay: Roundness and Structure

Verzenay is no stranger to recognition; it was one of the three original villages granted Grand Cru status along with Cramant and Aÿ. As one of Champagne’s leading terroirs, all the major Houses have a presence here; they are known as ‘vendangeoirs’, which is also the French word for the baskets that grape-pickers use.

Located in the middle of the slope on the north side of Montagne de Reims, between two protruding hills, the commune had a vineyard area of slightly more than a thousand acres, of which 86% is planted to Pinot Noir. The long-recognized quality of Verzenay grapes is more a result of elevation and exposure than any specific soil type—the vineyards provide multitude of different bases: chalk, limestone, sand, clay and more. As a result, the wines from Verzenay have great complexity which extend to somewhat masculine descriptors—dark in flavor with a distinctive gaminess and undertones of iron. As the climate warms, it is noted that the wines of Verzenay manage to retain their tautly-focused structure and small-shouldered roundness.

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet ‘Cuvée Diane Claire’, Grand Cru Verzenay 2009, Extra-Brut ($130)

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet ‘Cuvée Diane Claire’, Grand Cru Verzenay 2009, Extra-Brut ($130)

There are two ‘Diane Claires’ in the extended Penet-Chardonnet family, so pick your prestige-earner (though likely it’s both). 50% Pinot Noir and 50% Chardonnay, the wine originates in the best of Penet-Chardonnet’s Verzenay parcels; it is made primarily from with wines from the exceptional 2009 harvest, aged on lees since it was bottled in 2010 until its date of disgorgement. Amber in color, the wine is exceptionally aromatic and racy with grilled, spicy and iodized notes above green apple and orange zest.

(Bottled May 2010, disgorged March 2020, dosage at 5.6 grams/liter, less than 5200 bottles made.)

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet, Grand Cru Verzenay Lieu-dit “Les Champs Saint-Martin” Blanc de Noirs 2011, Extra-Brut ($110)

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet, Grand Cru Verzenay Lieu-dit “Les Champs Saint-Martin” Blanc de Noirs 2011, Extra-Brut ($110)

‘Les Champs St Martin’, consisting of 33-year-old Pinot Noir vines, sits at the relatively flat base of the Grande Montage de Reims. 100% Pinot Noir, the wine displays aromas of key lime, orange peel, raspberry and strawberry while on the palate, notes of white cherry, wet minerality, almond and berry jam lead to a soft and exceptionally generous finish.

(Bottled April 2012, disgorged March 2020, dosage at 4.8 grams/liter, less than 2000 bottles made.)

The Solera Or Perpetual Reserve: Getting The Balance Right For A Blend of Grand Crus Verzy And Verzenay

The term ‘solera’ brings to mind Spain’s unique and rather complex system of Sherry production where a large number of casks are employed and winemakers rely on fractional blending of older vintages into new to achieve maximum quality. Barrels in a solera are arranged in different tiers called ‘criaderas’; each tier contains wine of the same age while the oldest holds wine ready to be bottled. When a fraction of the wine is extracted from a given barrel, it will be replaced with the same amount of wine from the criadera that is slightly younger and typically less complex. This, in turn, will be filled up with wine from the next criadera, and so on.

In fact, the method used in Champagne is similar, though not identical, and is more accurately referred to as a ‘perpetual cuvée.’ Under this system, still wine is stored in tanks or barrels, and at bottling time, a portion is drawn from the oldest tank and the resulting empty space is filled with younger wine from another barrel. Thus, any given tank (beside the first) contains a blend of different vintages.

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet ‘Terroir & Sens’, Grand Cru Extra Brut ($68) Base-Wine 2012

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet ‘Terroir & Sens’, Grand Cru Extra Brut ($68) Base-Wine 2012

At 8000 bottles produced, this is a blockbuster for Penet-Chardonnet. 70% Pinot Noir and 30% Chardonnay, the cuvée blends grapes from both Verzy and Verzenay, finding qualities in each that build and synergize. Scents of golden apples, currant, raspberry and freshly baked bread straight from the oven are alive within steady stream of pinpoint bubbles.

(Bottled May 2013, disgorged October 2021, dosage at 5.2 grams/liter, less than 8000 bottles made.)

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet ‘Terroir & Sens’, Grand Cru Rosé Extra-Brut ($81) Base-Wine 2011

Champagne Penet-Chardonnet ‘Terroir & Sens’, Grand Cru Rosé Extra-Brut ($81) Base-Wine 2011

Partially aged in small oak barrels without malolactic fermentation, the salmon-colored ‘Terroir & Sens” opens with a deep, intense, slightly oxidative nose and toasty, matured and vinous palate of small red fruits, pralines and brioche. 70% Pinot Noir, 30% Chardonnay, the wine is a blend made from a selection of Grand Crus parcels in Verzy and Verzenay as well as from reserve wines.

(Bottled April 2012, disgorged October 2020, dosage at 5.2 grams/liter, less than 2000 bottles made.)

Notebook …

To Malo, Or Not To Malo

Malo is short for malolactic, but it’s also Spanish for ‘bad’. And at Penet-Chardonnay, the word translates either way. It is a process by which, after the initial yeast fermentation achieves desired alcohol level, the aggressive acidity left behind (especially in the cooler-weather grapes of Champagne) a secondary fermentation occurs via bacteria either naturally present in the must or added by the winemaker. Through the process, the wine’s sharp, green-apple malic acids are transformed into creamier lactic acids, the same acid that is found in milk—hence the root word in lacto-intolerance. It’s a useful trick, but there is no question that allowing or initiating malolactic fermentation changes some of the purity of taste that remains in wines that are aged and preserved via malic acid.

And any alteration in fruit expression is something that a passionate winemaker must weigh against benefits. Alexandre Penet considers some of the milky, buttery aromas that scream ‘malo’ to be detrimental to the honest voice he strives for, and as a result, he forgoes a step that most Champagne producers embrace.

Champagne Vintage Journal

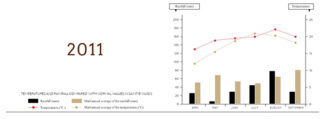

2008

If ever a vintage snatched victory from the jaws of defeat it was 2008. What began as a disaster—a cold winter preceded a chilly spring and a dank mid-summer, but then—as if a switch was thrown—the weather did an about-face and delivered bright, dry, sunny days which pushed the grapes towards phenolic ripeness. The freezing winter had served to fully shut down the vines, so when steadier weather eventually came, the grapes were in good health to take full advantage of the idyllic conditions. The cooler than average growing season also allowed grapes to ripen slowly, preserving much-needed acidity, which in Champagne is de rigueur.

Vintage 2008 was a sublime year for Champagne; if only the world’s economy had kept pace.

2009

The 2009 growing season was kissed by on high; a dry winter that left the water tables low was quickly put right by judicious springtime rains. Both budburst and flowering were successful and timely. A few vicious July storms affected Aÿ, but most of Champagne basked in sunshine, with August delivering warm days and cool, refreshing evenings. Dry heat helped prevent rot and disease from taking hold, and 2009 Champagnes tend to display rich, ripe orchard fruit that reflect the warm year. Acidity, though not searing, remains very much present and the wines continue to drink near the top of their game.

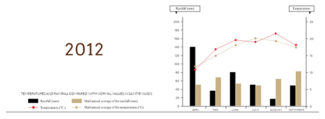

2010

Sorting in the vineyard was the name of the game in 2010; the growing season itself was lackluster, with pleasant summer weather morphing into drought and mid-August deluges saving the water tables, but grapes became diluted and waterlogged. Rot and unwelcome botrytis also became a serious problem, and the wet conditions continued through to the harvest in mid-September. Few Houses declared a vintage unless they had particularly good luck in the field.

2011

2011 was, overall, a forgettable vintage. Spring was much warmer and drier than usual with March setting a balmy stage for a hot and dry April and May. This led to a historically early flowering. As if in backlash, June and July were abnormally cool and humid and when the heat reappeared in August, it was with such a vengeance that caused some vines to shut down. By harvest, temperatures had cooled, but unpredictable rain still posed a problem. The intermittent storms tended to stall the development of grape sugars and acidity, leaving many wines lacking body. Chardonnay tended to perform better than its red counterparts, however, the wines tended to lack both structure and fruit character with little in the way of alcohol or acidity to make up for it.

That said, superbly positioned Houses like Penet-Chardonnet made acceptable wines that are probably reaching their peak now.

2012

Although the 2012 growing season tossed out plenty of curveballs, the vintage remains very strong. A warm winter slithered into an extremely wet spring in which both frost and a particularly vicious hailstorm devastated yields. Unsurprisingly, flowering was uneven and the tough conditions also opened the vines up to disease. However, August was a godsend; warm weather and sunny skies spun the vintage around. That month brought steady heat with temperatures sometimes rising so high that vines began to overheat. However, a smooth, sunny September allowed the grapes to finish the ripening process and Pinot Noir and Meunier were both able to fully ripen while well-rounded Chardonnay retained the necessary acidity.

Notebook …

The Landscape of Champagne

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it may take one a lifetime to understand it.

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ From north to south, seven main growing areas (The Montagne de Reims, The Grand Vallée, Vallée de la Marne, The Coteaux Sud d’Epernay, The Côte des Blancs, The Coteaux du Morin, Côte de Sézanne, Vitryat & Montgueux and Côte des Bar in the Aube) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

Although a single AOP covers all sparkling wine produced in Champagne, there are seven distinct sub-regions, each of which was originally associated with a single grape variety. Of course, geography changes throughout the area, so pockets of Champagne’s three main grape varieties (Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier and Chardonnay) can be found in each district.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Epernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

Beyond the overview relates to a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that complement or contrast when final cuvées are created.

- - -

Posted on 2022.08.30 in France, The Champagne Society, Champagne | Read more...

Second Thoughts: Fabled Château Ausone Re-releases Older Second Wine ‘Chapelle d’Ausone’ Three Vintages: 2011, 2012 and 2016 + 2019 Pre-arrival Special Price

In Bordeaux, a Château has the right to sell all of its production under the name of its domain, yet they rarely do. Based on vine age vs. current yield, producers occasionally replant vineyard plots and it generally takes a few years before the fruit reaches the level of quality required to justify either the Château’s name or the price it seeks for top releases. Parcels that are nearly—but not quite—ready to rock are generally downgraded to a second wine which, the consumer has every right to expect, are nearly—but not quite—at a quality level of the first.

This week’s featured offering represents one such second wine, ‘Chapelle d’Ausone’ from Saint-Émilion’s legendary Château Ausone. These wines, although ready to drink, are re-releases, meaning that they come directly from the estate itself, so the provenance is guaranteed. They are individually packaged in the original wooden box, stamped with name and vintage, ideal as a gift idea.

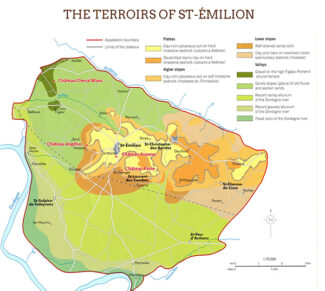

The town of Saint-Émilion lies just north of the Dordogne river in the final stages of its journey from the hills of the Massif Central to the Gironde estuary. It is a land from the pages of a storybook, renowned as much for its architecture and scenery as for its wine.

Unlike the wines of the Médoc, which focus heavily on Cabernet Sauvignon, Saint-Émilion is predominantly made from Merlot and Cabernet Franc. This is a matter of terroir; the clay and chalk rich soils around Saint-Émilion are generally cooler than those on the Médoc peninsula, and are less capable of reliably ripening Cabernet Sauvignon. Merlot makes up around two thirds of vines planted around Saint-Émilion, and continues to increase in popularity because of the softer, more approachable wine styles it produces. Both Cheval Blanc and Ausone may be seen as exceptions, since they are built predominantly around Cabernet Franc.

Château Ausone

The Most Confidential of Wines

‘Find a niche and fill it’ is one of the oldest, most revered bits of advice offered to entrepreneurs, but at Château Ausone, the mission statement is closer to ‘Find a niche and hide inside it.’

And that is because, despite being one of the only four Premier Grand Cru Classé A wines in Saint-Émilion (Ausone, Angélus, Cheval Blanc and Pavie), Château Ausone retains a relatively low profile, due in no small measure to its size. Encompassing a mere 17 acres in a region where 70% of the estates are larger than 50 acres, the output of Ausone is similarly restrained; even in spectacular vintages, fewer than 2,000 cases are produced. Château Haut-Brion, in contrast, releases ten times as many.

But that wine! Ask almost any French vigneron to name the best terroir in Bordeaux and the majority will say, without missing a beat, that it belongs to Château Ausone. Grown on Asteria limestone along terraces splashed in sunlight, protected from wind by geography and then nurtured in the cellar by Alain Vauthier (whose family has been making wine at Ausone since 1690), the typical profile of an Ausone Grand Vin is reticent and reserved in its youth, with a persistent elegance supplemented (especially in recent vintages) by a polished texture and aromatic complexity. With maturation, these elements combine to make Château Ausone a sublime secret.

Alain Vauthier is proud to be beholden to his land. He is pragmatic about the challenges that will keep it producing at the top of its game: “To improve wine quality, we change details according to the vintage, but the terroir remains the same. The climate may change—but very slowly—and Ausone will remain Ausone in style. I don’t see how the hand of humans can do much to alter terroir. Terroir is the conjunction of wind currents, sunshine and stability of soils linked to hydrology. I don’t see how we could change it.”

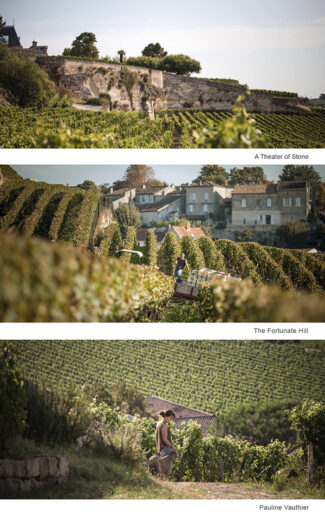

A Theater of Stone: Subterranean Tales

To delve further beneath the surface of Vauthier’s remarks, The Ausone estate is anchored to the side of the hill in a place called Roc Blancan; literally the ‘white rock.’ Besides providing the vines with an ideal foundation, Ausone limestone, has been worked by masons for seven hundred years. As a memento to their labors, there are Gallo-Roman galleries under the château and a maze of tunnels that double as wine cellars. Over the years, local families have taken up residence inside the abandoned local quarries and many are buried there: The thick limestone bank that lies above the property contains a small Romanesque chapel which stands, surrounded by vines, in one of Ausone’s parcels. Beneath it sits another treasure of Christian art—an underground rotunda with a fresco of the Last Judgement.

The Fortunate Hill: The Terroir’s Favors

The alignment of conditions at Ausone may sometimes seem like alchemy; surrounded by stone, the terraced vine parcels are in a natural amphitheater, sheltered from the wind while enjoying a perfect east south-east exposure. Sunshine is generous and working in concert with the Dordogne and Isle rivers that meet nearby, creates an ideal microclimate for winemaking. Some of the vines grow on a plateau of asteriated limestone, where their roots are anchored in crevices. On the hill, the vines delve deeply into earth supplemented with a layer of clay that provides welcome moisture when drought conditions prevail. Both growth environments are equally hospitable. Nowhere has this truth been more obvious (and more welcome) than during the horrendous frosts of 1892 and 1956. As a result, the estate boasts Cabernet Franc vines that are more than 100 years old, the oldest planted in 1906.

And at Château Ausone, Cabernet Franc is the name of the game: The vineyard is planted to 55% Cabernet Franc, 40% Merlot with the scant 5% Cabernet Sauvignon used primarily for Chapelle d’Ausone, the estate’s second label.

The Spirit and Practices: The Winegrower’s Task

Pauline Vauthier, Alain’s eldest daughter, is the eleventh wine growing generation at Ausone. Having started during 2005 vintage, she arrived well-prepared, having entered agricultural school at 15 and earning a degree in viticulture and enology, then working in South Africa at the Morgenster estate. “But I’ve always wanted to work at Ausone,” she admits, and today oversees all technical aspects at the famed château as well as at the family’s other properties in Moulin St-Georges, Château Fonbel and Château Simard.

She shares her father’s sensibilities, driving the estate towards organic viticultural practices in what she calls ‘educated agriculture: “Beyond the vines themselves, the wider ecosystem is also taken into account. Hedges, fruit trees and aromatic plants are grown as companions for the vines, stimulating a fertile exchange between species, backed up with natural applications of nettle, willow and valerian. A variety of wildlife is also preserved, including insects, birds and even bats, which all contribute in their own way to releasing the vital energy in the soil.”

Château Ausone rarely sticks to a singular regimen. Methods inspired by both organic and biodynamic procedures are implemented based on weather conditions, which the family agrees is the gentlest ways to craft wines. Says Alain, “The best tactic that man can adopt is discretion. From the vineyard through to the cellars, all the deliberate, measured practices employed pursue a single ambition, that of enabling the terroir to express itself as genuinely as possible.”

Ausone’s Second Wine: An Overture

Second wines are rarely an afterthought; in fact, they are better regarded as an overture—a wine that is often produced from younger vines or declassified lots, perhaps a slightly different cépage, but generally crafted by the same vigneron, using the same equipment and expertise, as the Grand Vin.

In short, a second label may be seen as an introductory course to the winemaker’s vision and can generally be identified by the absence of the word ‘Château’ on the label.

Chapelle d’Ausone is a prime example of this two-tiered, dual-philosophy excellence: Crafted under the same conditions as its elder sibling (the Merlot stands out more distinctly in Chapelle and mingles with subtle hints of Cabernet Sauvignon), it is a wine meant to be enjoyed younger than the Grand Vin, which may take fifteen or twenty years to unfurl. Chapelle is a great way to saturate the palate during the wait.

The re-release of several vintages of Chapelle d’Ausone from the estate itself is perhaps the best guarantee of its provenance and showcases the splendor of Ausone at a more rationale price point.

Individually Wooden-Boxed Bottles

These wines are contained within their original wooden boxes, stamped with the estate’s name and vintage; they are perfect for those eager to get at least one significant other off the Christmas list early.

These wines have been recently re-released by Château Ausone itself, so there is no doubt about the integrity of storage conditions during the intervening years.

After two excellent vintages, 2011 handed Bordeaux a return to reality. A sweltering spring meant quick bud break and flowering, a full two weeks earlier than 2010. From April through June, drought conditions were noted. By July, however, summer nearly disappeared, with low levels of sunshine and cool temperatures followed by a rainy August.

Yet, in general, these conditions had a far more devastating effect on the Left Bank, with Cabernet Sauvignon on gravel soils suffering the worst. Generally speaking, Cabernet Franc did much better, and estates planted to this variety in both Pomerol and Saint Émilion (like Château Ausone) produced nice, early-drinking wines with fresh fruit and some gentle tannins.

2011 Château Ausone ‘Chapelle d’Ausone’ Saint-Émilion Grand Cru ($199)

2011 Château Ausone ‘Chapelle d’Ausone’ Saint-Émilion Grand Cru ($199)

56% Cabernet Franc, 22% Merlot, 22% Cabernet Sauvignon. The wine has matured with earthy aromas of leather and forest floor above a core of fruit dominated by ripe cherry. The palate is supple and the tannins nicely integrated, finishing with dried fruit, black pepper and oak-driven butterscotch.

Overall, the 2012 vintage in Bordeaux was a challenge, and almost without exception the best wines came from older vines and long-established vignerons. Château Ausone was among them.

An extraordinarily wet April delayed both budburst and flowering; the latter did not occur until June. However, the flowering itself was beset with issues, from millerandage to mildew. The summer brought better weather, but a hot, dry August led to oppressive heat and drought. These harsh conditions caused some vines to temporarily shut down and the dry spell continued into September. Harvest was late, but those who delayed were rewarded, with Right Bank wines tending to fare better than the Left.

2012 Château Ausone ‘Chapelle d’Ausone’ Saint-Émilion Grand Cru ($199)

2012 Château Ausone ‘Chapelle d’Ausone’ Saint-Émilion Grand Cru ($199)

60% Cabernet Franc, 25% Merlot and 15% Cabernet Sauvignon. Rich, broad and expansive, with raspberry jam and smoky licorice above notes of plum, blueberry and black raspberry. Finishes with the powdered-chalk minerality one excepts from an Ausone. 500 cases made.

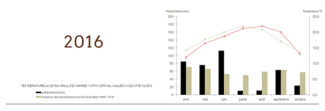

Like the rest of Bordeaux, Saint-Émilion experienced an unusually warm and wet winter with humid conditions continuing throughout the spring. Sporadic rains fell, serving to bolster water tables in the soil, although the lack of sun during the spring months meant budburst was slow to arrive. Eventually, the clouds cleared, and early June saw bright summer sunshine, which prompted a successful flowering. The early rains proved vital to the drought conditions that developed over a hot, dry summer.

Overall, the 2016 vintage for Saint-Émilion was excellent and a wide range of brilliant wines were made from easy-drinking second wines to sophisticated Grand Vins that will reward long-term cellaring.

2016 Château Ausone ‘Chapelle d’Ausone’ Saint-Émilion Grand Cru ($249)

2016 Château Ausone ‘Chapelle d’Ausone’ Saint-Émilion Grand Cru ($249)

A blend of 56% Cabernet Franc, 22% Merlot and 22% Cabernet Sauvignon. The high percentage of Cab Franc in this assemblage is the result of replanted plots that are not quite ready for the Grand Vin. The wine is exceptionally floral, with rose-petal and violet aromas floating above fleshed-out raspberry and loganberry notes and plenty of firm tannins and delicious acidity.

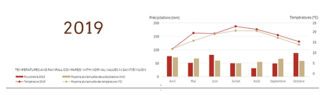

2019 Pre-Arrival* Special Offer

In Saint-Émilion, the 2019 vintage was exceptionally good. A benign winter moderated into a balmy spring and benevolent weather reigned supreme until April, which brought a significant cold snap. Like neighboring Pomerol, threats of frost hung in the air, but as it has in the past, Château Ausone weathered the storm without damage. A hot, dry summer emerged with cool nights that preserved essential acidity and aromatics. A hot July saw two significant rainstorms, which helped break up the heat while rehydrating the vines. September then marked the start of a golden autumn, interrupted only towards the end of the month by heavy, but welcome rainstorms. The harvest ran from mid-September to the beginning of October with Merlot first in line to be picked.

2019 Château Ausone ‘Chapelle d’Ausone’ Saint-Émilion Grand Cru ($199)

45% Merlot, 45% Cabernet Franc, 10% Cabernet Sauvignon, with 85% new oak; a blend of wine from young vines with a few barriques of declassified Ausone. Brilliant flashes of juicy blackberry, warm plum compote and redcurrant jelly in the forefront with suggestions of sassafras, cedar chest, menthol and aniseed throughout. Fewer than one thousand cases made.

* The wine was released in April 2022 and will arrive late September 2022.

- - -

Posted on 2022.08.25 in France, Bordeaux | Read more...

A Veritable Viticultural Revolution at Domaine Vacheron: Sancerre Cuvées Reflective of The Region’s Wide Soil Diversity in White, Rosé and Red. (6-Bottle Pack $318)

Just as the Loire River runs through the heart of France, Sancerre pierces the heart of summertime and provides an unadorned synthesis of the scents we associate with the easy season: The whites are redolent of cut grass and Meyer lemon, the rare reds are full of luscious cherry and campfire smoke and the rosés are all about wild strawberries and picnic watermelon. These wines are some of the most elegantly perfumed in the world, meant to be enjoyed as much with the nose as with the mouth.

This week’s package is a selection from one of Sancerre’s elite estates, Domaine Vacheron. The featured bottles reflect a wonderful cross-section of Vacheron’s variety with samples from the lieux-dits that form the best of their acreage, including Guigne Chèvre, En Grands Champs, Paradis, and Chambrates.

Jacqueline Friedrich opened ‘The Wines of Loire’ with her description of the domain: “Domaine Vacheron goes from strength to strength and shows no signs of stopping.”

Wine Siblings: Sancerre and Chablis

Brothers from another mother or sisters from another mister; either way, the land beneath Sancerre and Chablis springs from the same prehistory. Classified in the middle of the 18th century by French geologist Alcide d’Obigny while he was working near the English town of Kimmeridge, he identified a unique layer of dark marl and called it ‘Kimmeridgian.’

Still, as in siblings, there are distinct differences in the DNA of English Kimmeridgian and French Kimmeridgian. The French layer is a relatively uniform chalky marl with thin limestone containing rich layers of seashells. This is because strata formed from the post Jurassic period continued to be deposited in the shallow sea areas which once covered part of France. The way these layers interact is key to the reason that French Kimmeridgian soils produce some of the world’s most heralded wine. The marly soil provides good structure, ideal water-retention and is easy to cultivate while hard limestone Portlandian contains numerous fossil fragments and, having been repeatedly shattered by frost, offers good aeration and ideal drainage along gentle slopes.

Chablis is a significant part of the Kimmeridgian chain; mid-slope vineyards in Chablis match almost perfectly to the Kimmeridgian outcrop, with the soft, carbonate-rich rock being covered by Portlandian limestone and supported by other limestone deposits. Sancerre, meanwhile, sits on top a fault ridge; the eastern side has a layer of Cretaceous soils while the west side is covered with brush and gravel slopes. Further west the best vineyards sit on the classic Portlandian-Kimmeridgian soil combination, producing a classic example of ‘terroir’.

Sancerre: Purity Manifest

The almost clichéd emphasis placed on Sancerre’s purity is a result of two factors: First, the region is relatively northern, so a hallmark of nearly all Sancerre—red, white or pink—is its bright acidity—preserved in the grapes by cool nights and temperate days. The pH of a wine determines its mouthfeel, and the higher the acidity, the more sizzling is the sensation of freshness and clarity on the palate, often described as ‘purity’. Of equal importance, very little oak is used in the maturation process of wines from Sancerre, and the flavors associated with oak—butter, clove, vanilla and caramel—however desirable in Burgundy, tend to mask some of the fruit-driven notes. It’s one of the reasons that oak-free Chablis is considered the purest incarnation of Chardonnay, and likewise, the neutral barrel or stainless steel/cement aging of Sancerre’s Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Noir and occasionally Gamay offers the best results for preserving the natural flavors inherent in the juice.

At Vacheron, purity is not only made manifest in the final product, but in the attitude: “Wine is just about mineral and being organic,” Jean-Laurent Vacheron says simply.

Domaine Vacheron

Certified by Biodyvin in 2005, the move to organic agriculture by the two young cousins Jean-Laurent and Jean-Dominique Vacheron has revolutionized the quality of the old domain’s output. No synthetic material is used in the vineyard, harvests are carried out exclusively by hand and fertilizer is only what matures in the compost pile. All the biodynamics in the world does not change location, and in fairness, the cousins inherited some of the most coveted parcels in the appellation—acres that had been in the Vacheron family for nine generations—and then embarked on a series of shrewd land purchases. They now oversee well over a hundred acres of prime vineyard land.

Jean-Dominique & Jean-Laurent Vacheron • Domaine Vacheron • (Hejvin)

Using a Burgundian approach, they vinify parcels by terroir and blends that vary from year to year. Although Sancerre was predominantly a red wine-producing region until phylloxera decimated it in the late 19th century (with Sauvignon Blanc planted in its place) in much of modern Sancerre, Pinot Noir is an afterthought. At Vacheron, it receives special focus, and on soils just a couple of hours west of Nuits-Saint-Georges.

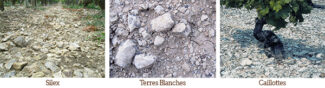

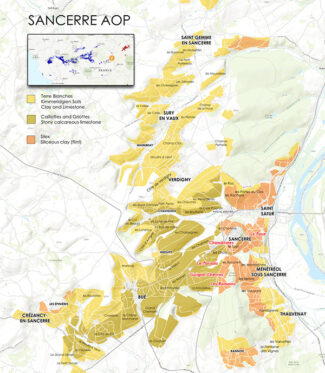

As to soils, there are three primary types that typify Sancerre; silex, or flinty soil, runs in a narrow band along a fault line that passes under the town of Sancerre; Kimmeridgian marl, also known as ‘terres blanches’ because the chalky clay soil turns white in dry periods; and ‘caillottes’, or Oxfordian limestone. Each type imprints its own recognizable character on the wine— Oxfordian soils produce wines that are delicate and perfumed; Kimmeridgian soil yields fruiter wine whose aggressive acidity make them very age-worthy while silex yields brooding, mineral-tinged wines.

The flint soil is found primarily in the eastern part of the appellation and across the river in Pouilly Fumé, and almost all of Vacheron’s holdings are on this mineral-rich soil type. Says Jean-Dominique Vacheron: “Silex produces vertical, long-aging Sancerre bottlings and our biggest aim is to let this shine. Our Sancerre blanc comes from vines planted on the fault line between silex and caillottes.”

Sum of The Parts

Before the Vacheron cousins took over the domain, vinification of specific terroir was not commonly done in Sancerre, nor were altering blends from year to year. Certainly, they are the only producers in the region with a barrel-room made up of casks sourced from Domaine Romanée Conti. This is not an attempt to ‘be’ Burgundy, according to Jean-Laurent Vacheron, “although you could make some money thinking like that.” He adds, “There are two reasons we are doing this; first it is because we like to be here and secondly, it is to keep within the ramparts of Sancerre. After all, what is Sancerre if there are no winemakers?”

He has a point: Like much of rural France, the population of Sancerre has halved over the past century and now has a population less than 1500. “Winemakers have also been part of this exodus so, where there was once 20 winemakers within the town walls there are now just two or three,” says Jean-Laurent.

Certainly, there are those who argue that Jean-Laurent and Jean-Dominique Vacheron are the best winemakers in Sancerre. The ‘two Jeans’ farm eight lieux-dits that, taken individually, are among the most highly regarded wines in France, but taken as a ‘sum of the parts’, the cousins have created a unique Vacheron style that, like any successful synergy, is somewhat greater than the whole. As a further nod to the future, both Jeans have sons studying viticulture and intending to carry on the family tradition.

The offered 6-bottle package is comprised of two of each of the following wines at $318.

Domaine Vacheron, 2020 Sancerre Blanc ($51)

Domaine Vacheron, 2020 Sancerre Blanc ($51)

Aged in stainless steel tank for 8 months, this is a remarkable complex wine for a ‘starter’ Sancerre; it has the full-blown profile of an ethereal Loire Sauvignon Blanc with notes of gooseberry, nettle and boxwood behind a zesty core of lime, passion fruit, and the wonderful chalkiness that typifies a top Sancerre with a finish tinged with smoke.

Vacheron ‘Le Rosé’, 2021 Sancerre Rosé ($54)

Vacheron ‘Le Rosé’, 2021 Sancerre Rosé ($54)

Very few rosés are allocated or considered collectable; this is a noted exception from Vacheron. Made from biodynamic Pinot Noir, its discrete nose opens gradually, evoking scents of ripe, freshly sliced strawberries, orange zest, chamomile and cherry tart. It leans more toward citrus in the mid-palate and finishes with grapefruit tones.

Domaine Vacheron, 2018 Sancerre Rouge ($54)

Domaine Vacheron, 2018 Sancerre Rouge ($54)

Red wine makes up about 20% of Vacheron’s production. This one hails from plots of thin limestone soils where the vine roots struggle and produce small, intensely concentrated berries. Traditionally, the Vacheron cousins were one of the few Sancerre producers who could coax depth and richness from Pinot Noir, and with the climate warming, their reds keep improving. As always, the grapes are hand harvested, whole cluster pressed and fermented with ambient yeast, giving unique character to a spicy nose of ripe black cherries, dark chocolate and pepper. This is a seamless and silken Pinot Noir with lingering freshness, grip and salinity on the finish.

The Twin Years: 2018 and 2019

The back-to-back vintages 2018 and 2019 represent something of a climactic miracle. Even as a stand-alone, 2018 is considered to be one of the most exceptional vintages seen in the region for half a century. Taken together with a spectacular 2019, they are twin towers of triumph.

2018 began with fantastic spring that allowed for successful flowering and fruit set without any of the usual problems that normally occur with rain, hail or frost, and a hot summer developed the ripe semi-tropical flavors associated with the best Sauvignon Blanc. 2019 was a bit cooler, but produced grapes where the coveted acids that reign in aggressive fruit notes.

Tapping the source directly, Vacheron comments, “2018 and 2019 are very similar in the way they are constructed, even if the alcohol is slightly higher in 2018. The two vintages tend to show that it is possible to make wines that have good freshness despite low acidities because the minerality superseded the acidity. 2018 is without a doubt a vintage that will mark people’s memories, and will remain a reference in Sancerre. It’s the kind of vintage that helps grow a heighten a generation of wine makers and their appellations.”

Vacheron’s Sancerre Climats:

Expressing Localities

Sancerre is generally made from a single cultivar, but the geography is such that many permutations influence the style of an individual wine. Altitude broadly varies from 300 feet to over a thousand; the bands of soil types have already been mentioned, and a hilly landscape that can harness more warmth or less depending on the aspect.

A significant reason that the Vacherons have embraced biodynamics with such passion is that they consider it among the best agricultural technique to showcase the distinct terroirs of their holdings. Sancerre is not a land of designated ‘crus’—Burgundy’s way of denoting the best sites—and instead relies on named vineyards called ‘climats’ or ‘lieux-dits’. These may be considered the crème de le crème among Sancerre’s vineyards and some (Les Monts Damnés and Le Cul de Beaujeu) may be better known than others. The Vacherons have parcels in most of the top lieux-dits, even those less familiar to many of Sancerre’s most ardent fans, including ‘Le Paradis’ and ‘Chambrates’, just outside the Sancerre city walls.

Climat ‘Chambrates’ Domaine Vacheron 2019 Sancerre Blanc ($75)

Climat ‘Chambrates’ Domaine Vacheron 2019 Sancerre Blanc ($75)

Chambrates is located on a plateau above Le Paradis on limestone and red clay soils. Citrus and vanilla ice cream on the nose; the palate is filled with tension and vitality, ranging between notes of candied orange peel, grated ginger, lemon curd and the elusive quality of stoniness that appears at the finish of the best Sancerre.

Climat ‘Chambrates’ Domaine Vacheron 2018 Sancerre Blanc ($89)

Climat ‘Chambrates’ Domaine Vacheron 2018 Sancerre Blanc ($89)

Climat ‘Guigne-Chèvres’ Domaine Vacheron 2019 Sancerre Blanc ($75)

Climat ‘Guigne-Chèvres’ Domaine Vacheron 2019 Sancerre Blanc ($75)

Guigne-Chèvres is a north-facing site with a complex terroir of silex above a shallow layer of limestone and red clay. A tightly-textured wine boasting a strong minerality that rises from crisp citrus and savory herbal flavors.

Climat ‘Guigne-Chèvres’ Domaine Vacheron 2018 Sancerre Blanc ($89)

Climat ‘Guigne-Chèvres’ Domaine Vacheron 2018 Sancerre Blanc ($89)

Climat ‘Les Romains’ Domaine Vacheron 2019 Sancerre Blanc ($75)

Climat ‘Les Romains’ Domaine Vacheron 2019 Sancerre Blanc ($75)

Les Romains is a flint terroir located in the eastern part of Sancerre where the soil bears a strong resemblance to the terroir across the Loire River in Pouilly-Fumé.

Climat ‘Les Romains’ Domaine Vacheron 2018 Sancerre Blanc ($89)

Climat ‘Les Romains’ Domaine Vacheron 2018 Sancerre Blanc ($89)

Climat ‘Le Paradis’ Domaine Vacheron 2019 Sancerre Blanc ($75)

Climat ‘Le Paradis’ Domaine Vacheron 2019 Sancerre Blanc ($75)

A safe bet in dry and warm vintages due to its old vines, the Vacherons own two acres Le Paradis on a steep, south-facing slope where the soil is so thin and poor that the vine roots grow deeply into fissures in the bedrock.

Climat ‘Le Pavé’ Domaine Vacheron 2018 Sancerre Blanc ($195)

Climat ‘Le Pavé’ Domaine Vacheron 2018 Sancerre Blanc ($195)

A cooler, east-facing vineyard and 30-year-old vines grown on ‘marnes de crétacé’—the fossilized marine life that typifies a band of chalky soils running through Champagne and Chablis.

Climat ‘Le Pavé’ Domaine Vacheron 2017 Sancerre Blanc ($210)

Climat ‘Le Pavé’ Domaine Vacheron 2017 Sancerre Blanc ($210)

Climat ‘Belle Dame’ Domaine Vacheron 2018 Sancerre Rouge ($105)

Climat ‘Belle Dame’ Domaine Vacheron 2018 Sancerre Rouge ($105)

The first site-specific cuvée for the Vacherons, introduced in 1995 from one of the best known vineyards in Sancerre, beloved for its pure flint soils.

Climat ‘Belle Dame’ Domaine Vacheron 2016 Sancerre Rouge ($144)

Climat ‘Belle Dame’ Domaine Vacheron 2016 Sancerre Rouge ($144)

Notebook …

2022 August Report: Intense Heatwave Parches France’s ‘Garden’, Precipitates Premature Harvest

August 15 – Forced to start picking grapes much earlier than normal because of torrid temperatures, winemakers across France are worrying that grape quality will suffer from the climate-induced stress.

In the Loire, the so-called ‘Garden of France’ where parts of the Loire River have dried up completely, the crisis is magnified and the grape harvest is, by necessity, occurring earlier than normal.

The exceptionally dry conditions spread from the rugged hills of Hérault along the Mediterranean, where picking is already underway, to the normally verdant Alsace in the northeast. Waves of extreme heat this summer accelerated grape maturation, meaning harvests had to begin one to three weeks early or more — in Languedoc-Roussillon, some growers even started in late July.

Like other farmers, French winegrowers have been grappling for years with increasingly common extreme weather including spring freezes, devastating hailstorms and unseasonably heavy rains.

But this summer’s combination of a historic drought — July was the driest month on record since 1961 — and high temperatures are taking a particular toll on vineyards. Only 10 percent of France’s winegrowing parcels use artificial irrigation systems, which can be difficult or prohibitively expensive to install.

Although grapes are heartier than most crops, especially old vines whose roots delve deeply into the subterranean bedrock to find water, even they can withstand only so much. When water is scarce, the vines suffer “hydric stress” and protect themselves by shedding leaves and no longer providing nutrients to grapes, stunting their growth.

In Alsace, “we haven’t had a drop of rain in two months,” said Gilles Ehrhart, president of the AVA growers’ association. “We’re going to have a very, very small harvest” after picking begins around August 26, he said.

And when temperatures surpass 100 degrees Fahrenheit, “the grape burns — it dries up, loses volume and quality suffers” because the resulting alcohol content “is too high for consumers,” said Pierre Champetier, president of the Indication Géographique Protégée (IGP) for the Ardèche region south of Lyon. Champetier began harvesting Monday, when “40 years ago, we started around September 20,” he said. Now he worries that global warming will make such premature harvests “normal.”

– Quality at Risk –

Some winemakers are still holding off in hopes of rain in the coming weeks, such as red grape producers in Hérault, where harvests should begin as usual in early September.

In Burgundy, which two years ago saw its earliest harvest debut — August 16 — in more than four centuries of keeping track, picking will start at cellars in Saone-et-Loire around August 25.

But just south in the Rhône Valley, “the heatwave has accelerated maturation by more than 20 days compared to last year,” according to the Inter-Rhône producers’ association.

They nevertheless hope grape quality will hold up, as do Champagne growers in the northeast, where harvesting will begin late August — though yields are set to fall nine percent year-on-year because of a brutal spring cold snap and hailstorms.

- - -

Posted on 2022.08.18 in Sancerre, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Loire | Read more...

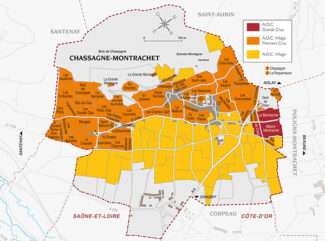

Burgundy Paradox: Red Gems from The Land of Chardonnay’s Gold Standard, The Triumvirate of Meursault, Chassagne-Montrachet and Puligny-Montrachet (5 Bottle Pack $358)

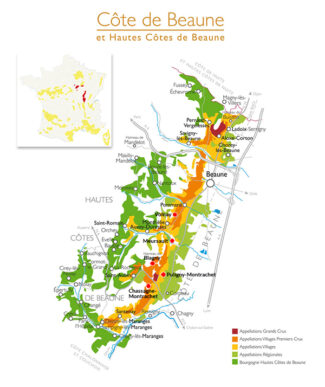

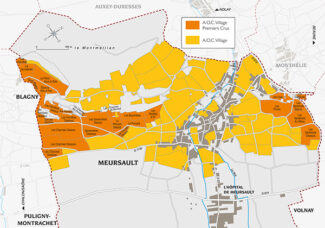

Few people would argue that the triumvirate of Meursault, Chassagne-Montrachet and Puligny-Montrachet produces some of the greatest white wines on the planet, but like that heavy metal band who releases a strangely poignant acoustic song, the reds of these three legendary appellations—however few and far between—are chart toppers in their own category.

In fact, for most of its history, Chassagne-Montrachet was more renowned for red wine than for white, and it wasn’t until the 1970s that a shift began to occur; today, Chardonnay outnumbers Pinot Noir 75% to 25%, gaining ground with each passing year. In Meursault, there are only 25 acres given over to Pinot Noir, and a mere three of these are Premier Cru. In Puligny, the situation is better, with Premiers Crus Les Caillerets, Le Clavoillon ou Clovaillon and Les Pucelles being superb terroirs for Pinot Noir. In fact, Les Pucelles and Les Caillerets are both mentioned as obvious candidates for Grand Cru classification.

The five bottles that represents this week’s package are excellent examples of this odd beast, red wines that hail from beneath Burgundy’s whitest flags.

Geology & Geography are Destiny