An Invitation to Join ‘The Champagne Society’

JOIN THE CHAMPAGNE SOCIETY

Subscribe to our bimonthly Champagne Club. Please, call us at 248-398-0030 or email elie@eliewine.com

As a member of The Champagne Society, you’re in a select community of like-minded folks who appreciate the exceptional in life and recognize that sparkling wine is a superlative among man’s culinary creations. A bottle of Champagne is selected for you bimonthly. You will be drinking some of the best Champagne ever produced.

As a member of The Champagne Society, you’re in a select community of like-minded folks who appreciate the exceptional in life and recognize that sparkling wine is a superlative among man’s culinary creations. A bottle of Champagne is selected for you bimonthly. You will be drinking some of the best Champagne ever produced.

All selected wines are from passionate grower-producers or small houses deeply connected to the subtleties of each of their vine parcels and who believe that wine is made in the vineyard. Many of these wines are highly allocated, many bought directly, and we quite often only have access to a few cases of a particular cuvée.

As a member of The Champagne Society expect the following benefits:

• The selected Champagne quite often is not available in any other wine shop in Michigan and only in a few places, if any, in the country. We compete with savvy wine buyers in the European and the Far East markets to secure some of the allocations from these sought-after makers.

• The selection is released every other month and ready for pickup by the 10th of that month, or shipped if you prefer. Expect a new bottle in February, April, June, August, October and December.

• The price is always less than $110 and reflects 15% discount of the store price when we have additional quantities to sell to non-members. Champagne available, members may purchase any number of additional bottles at the same discounted price.

• We notify you via email when the installment selection is released in a newsletter that profiles the producer and the cuvée chosen. The newsletter is also posted on www.eliewine.com . Only then your credit card is charged and you are sent a separate purchase receipt.

• You can pause or cancel your membership at any time.

September 22, 2025

A Small Seat at Champagne’s Organic Table

The Association des Champagnes Biologiques (ACB) has been quietly shaping Champagne’s future since 2009, uniting growers who farm organically in one of the most disease-prone climates on earth. This fall, Elie Wine Co. became the first American member—a modest milestone that feels less like a trophy than a handshake across the Atlantic.

The Association des Champagnes Biologiques (ACB) has been quietly shaping Champagne’s future since 2009, uniting growers who farm organically in one of the most disease-prone climates on earth. This fall, Elie Wine Co. became the first American member—a modest milestone that feels less like a trophy than a handshake across the Atlantic.

The ACB’s members are farmers first, winemakers second, and their bottles are already familiar to Elie Wine Co. clients. Aurélien Laherte channels Chavot’s vineyards into precise, expressive parcels. Benoît Marguet’s Ambonnay Champagnes are biodynamic firebrands. Lacourte-Godbillon brings grower intimacy to the Montagne de Reims. Fleury, pioneers of biodynamics since 1989, continue to prove what’s possible. Clandestin, the work of Benoît Doussot and Etienne Calsac, pushes the edges with razor-cut wines. And alongside them, Hubert–Noiret and Pascal Lejeune farm and craft with a quiet persistence that gives voice to their corners of the Marne.

To be counted among them as a merchant-member is humbling. It affirms that telling their story—listening, learning, and placing their wines in curious hands—can play its own small role in sustaining the movement.

Champagne, after all, is not only about labels and luxury. It’s about vines clinging to chalk, farming without shortcuts, and the patience to let time and soil speak. To sit at this table, even from afar, is an honor.

Elie Wine Co.

Member of the Association des Champagnes Biologiques

- - -

Posted on 2025.08.05 in France, The Champagne Society, Champagne | Read more...

The Champagne Society August 2025 Selection: Champagne Lacourte Godbillon

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon

Terroir Evangelism

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘Mi-Pentes’, Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut ($92)

The soul of Champagne has always been finesse, and a Cellar Master’s decision to balance blends (in a search for complementary aromas and personalities) or to bottle a single variety is intended to be a statement. Listening to the winemaker’s voice in different incarnations of the same art form is to enjoy an ever-changing dialogue between man and grape.

The soul of Champagne has always been finesse, and a Cellar Master’s decision to balance blends (in a search for complementary aromas and personalities) or to bottle a single variety is intended to be a statement. Listening to the winemaker’s voice in different incarnations of the same art form is to enjoy an ever-changing dialogue between man and grape.

Listen to the conversation with your nose and palate and decide which one resonates best with your personality. Society members receive an additional 10% discount of the already discounted prices, so make sure your summer get-togethers are well fueled with ice-breakers.

Elie

Petite Montagne-de-Reims: The Expression of Terroir

In French, the word ‘petite’ often to refers to a ‘lesser’ commodity, but with La Petite Montagne, the reference is to elevation. This lower elevation means warmer weather, even in Champagne’s northerly climate, and in certain villages, the soils contain more sand, making it an ideal environment for growing Meunier.

Meunier accounts for approximately half of the plantings in the Petite Montagne, with Pinot Noir making up 35% and the rest Chardonnay. It is a growing conviction among growers of the modern era that Meunier is a Champagne grape whose time has come, especially as an age-worthy variety. Emmanuel Brochet of Villers-aux-Noeuds says: “People claim that Meunier ages too quickly, even faster than Chardonnay. I disagree. The curve of evolution is different. Meunier is quick to open and more approachable in youth, but then it becomes quite stable. Chardonnay tends to open later, but old Meunier remains very fresh and lively.”

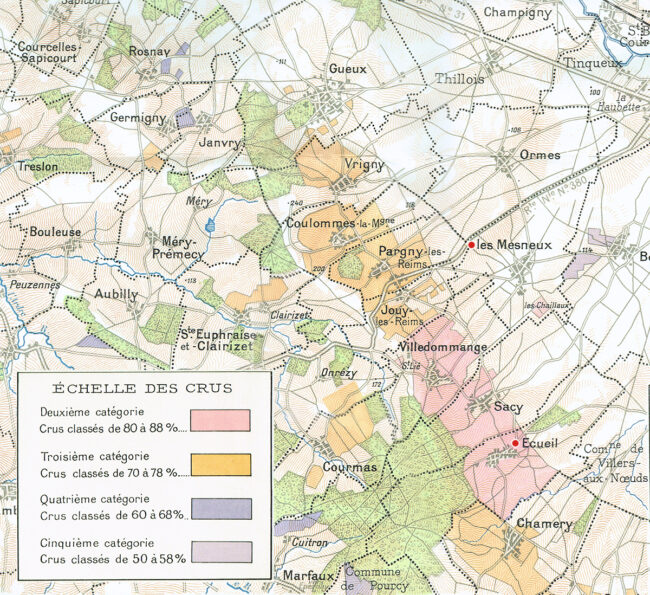

• Petite Montagne-de-Reims • Premier Crus Village Écueil & Les Mesneux

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon

Géraldine Lacourte & Richard Desvignes

Champagne with Roots: Single Parcels, Singular Village

The transition from simply growing grapes to becoming a winemaker who ferments their own crop is taking modern sensibilities by storm, but the family of Géraldine Lacourte took the leap in 1947. Géraldine says, “The Lacourtes on my father’s side and the Godbillons on my mother’s side once sold all their harvest to the major Champagne Houses. It was, perhaps, not a labor of love so much as a labor of survival—my grandmother talked about being in vineyards from five in the morning until eight at night, with the children joining them after school. Then in 1947, shortly after returning from the war, they began a new adventure: Producing and marketing champagne under the names Lacourte-Labasse and Godbillon-Marie. So popular was their wine that they were soon filling their customers’ car boots with bulk orders!”

Géraldine’s parents took the reins in 1968 and established the Champagne Lacourte-Godbillon label. “At first it was no more than a few thousand bottles. Bottling and disgorgement would be done at the back of a courtyard. But the most important thing was my father’s understanding that the best Champagne was made only from top quality work in the vineyard. His whole career was dedicated to this ethos.”

Géraldine Lacourte and Richard Desvignes, Champagne Lacourte Godbillon

In 2006, she and her husband Richard Desvignes left urban jobs and returned to their ancestral roots: “Our 21 acres of vineyards is planted 85% to Pinot Noir and 15% to Chardonnay, all of it in Écueil except for just 1.2 acres in the neighboring village of Les Mesneux. Our vines have an average age of 30 years.”

Richard explains, “Winemakers from all over the Montagne district have long bought Pinot Noir vine plants from Écueil. There was even a school here where they could learn how to graft these stocks. Up until a few years ago we bought our Pinot Noir plants from the local nursery, but going forward, we will be implementing our own ‘massale selection’ of the best plants for cuttings in our own parcels of vines, in order to preserve this heritage.”

The terroir is characterized by an incredibly diverse sub-soil. Some parts are predominantly sandy over the deep chalk, others composed of ‘sparnacian’ clay and shallow chalk at the bottom of the hillsides, similar to the soils of Les Mesneux.

Reframing Champagne: Single Village Premier Cru Écueil

Écueil is one of a string of Premier Cru villages that extend along the slopes of La Petite Montagne. The commune itself has a scant three hundred citizens and covers 1700 acres, of which slightly under four hundred are planted to grape vines. Unlike many of the surrounding villages, Écueil is a Pinot Noir stronghold; Pinot Noir represents 76% of the commune’s production, the remainder being split equally between Chardonnay and Pinot Meunier.

The growers of Écueil are often the lords of tiny holdings, many passed down through generations; they cultivate them meticulously and are deeply connected to their land. As a result, they can boast an intellectual understanding every corner of their vineyards and the personal nuances of the family terroir. To blend away these subtleties with adulterations from other plots, other villages, seems almost silly to those of us who appreciate the reflection of origin.

Single village Champagnes, or ‘monocrus,’ are coming into vogue for this very reason.

The vineyards of Écueil are mostly east-facing, but the several lieux-dits have more southerly exposures. These highly-prized sites have a considerable percentage of sand mixed in with the clay, offering the wines power, lift and elegance. An individual vineyard may have select plots as soils vary from sand atop deep chalk at the top of the slope to clay over shallow chalk at the bottom.

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘Terroirs d’Ecueil’, Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Extra-Brut ($58)

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘Terroirs d’Ecueil’, Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Extra-Brut ($58)

85% Pinot Noir and 15% Chardonnay grown on the characteristic silty loam soils of Écueil. The wine is a blend of vintages; 47% from 2020, which spent nine months on the lees, and 53% reserve wine from 2019 and 2018. The wine is crisp and racy with acidity, showing notes of citrus, brioche toast and lime zest.

It was bottled July 2021, disgorged on January 2024 and dosed at 3.5 grams per liter, with production at 36,300 bottles.

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ”Terroirs Épanouis #2’, Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Extra-Brut ($99)

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ”Terroirs Épanouis #2’, Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Extra-Brut ($99)

‘Épanouis’ is a dual meaning word, both of which apply: It translates to ‘blossoming’ and ‘contented.’ 85% Pinot Noir, 15% Chardonnay using a base of 44% 2016 reserve, which spent nine months on the lees enhanced with 56% reserve wine from 2015 and 2014. The wine is aromatic with a powerful nose showing toasted almonds and candied fruits, broad and sublime on the palate.

Bottled in July 2016; disgorged January 2024 and dosed at 1.5 grams per liter. A scant production of one thousand bottles.

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘Mi-Pentes’, Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut (Sold Out)

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘Mi-Pentes’, Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut (Sold Out)

‘Mi-Pentes’ is a French term meaning ‘mid-slope,’ and this is the location of the vines that make up this pure Pinot Noir from Écueil. The wine is a blend of 66% wine from the 2020 vintage which spent nine months on the lees (44% in large oak foudres) and the rest from 2019 reserve.

Bottled in July 2021, using the old ‘tirage sur liège’ method, in which (instead of crown caps) the bottles are sealed with natural cork for their all-important second fermentation; the porosity of the cork allows the wine to mature longer on the lees and thus develop more complexity over a considerable period. Flecks of amber in the hue reflect barrel contact; the wine shows peach, nectarine and toasted nuts.

Disgorged in May 2024 and dosed at 2.5 grams per liter.

Production: 4650 Bottles

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘R’, Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Rosé Extra-Brut ($64)

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘R’, Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Rosé Extra-Brut ($64)

‘R’ for rosé; 100% Pinot Noir with 6% vin rouge. 55% from the 2021 vintage, which spent nine months sur-lie—40% in large oak barrels—blended with 45% 2020 reserve wine. It was bottled in July 2022 and disgorged May 2024 with 3 grams per liter dosage. The wine shows spicy notes of cinnamon, nutmeg and ginger mingling with blood orange and raspberries.

Production: 5360 Bottles

Precise Champagne: Écueil’s Single Parcels, Lieux-dits

The ‘parcellaire’ approach takes microscopic expressions of a single village even further; site-specific Champagnes celebrate the terroir of an individual vineyard, or even a named portion of a single vineyard, a lieu-dit. In Burgundy, this is common practice; in Champagne (lacking the pervasive marketing tactics of the Grand Marques) it remains an anomaly.

But the consumer will-out, and if these wines take hold of the public’s imagination as firmly as they have done in Burgundy, this style may well dictate the future, especially among those of us who insist that wine reflect the minutia of the soil in which it originates.

The Écueil lieux-dits mentioned above consist of the following:

Les Aillys; a vineyard site immediately to the north of the village itself. Most of the site is south-facing on a gentle slope.

Les Chaillots; a vineyard site in the northern part of Écueil, northwest of the village itself, on the border to Sacy. The site is located in the upper part of the slope, but is rather flat.

Derrière Moutier; an east-facing site situated in the slope immediately above the graveyard, to the west and northwest of it.

Les Gillis; a southeast-sloping vineyard site in the southern part of Écueil, on the border to Chamery. The site is located mid-slope, just above/west of the D26 road.

Les Hautes Vignes; a southeast-facing vineyard site in the southern part of Écueil. It is located immediately above/west of the D26 and borders to Les Gillis in southwest.

Le Mont des Chrétiens; a southeast-sloping vineyard site in the southern part of Écueil, on the border to Chamery. The site is located in the upper part of the slope, close to the edge of the forest, and borders Les Gillis, among others.

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘C.’, 2016 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Extra-Brut ($139)

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘C.’, 2016 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Extra-Brut ($139)

100% Sélection Massale Pinot Noir from the lieu-dit Les Chaillots planted in 1966, a plot prized for its sandy surface and tuffaceous subsoil. The wine was bottled in July, 2017 using the old tirage sur liège method and disgorged on May 9, 2023 with 1.5 grams per liter dosage, and bottled with cork and staple. Rich and refined with notes of fig leaf, black tea and fresh spices blended into a firm, structured palate.

Production: 1658 bottles; 30 Magnums.

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘C.H.V.’, 2019 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut ($105)

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘C.H.V.’, 2019 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut ($105)

‘C.H.V.’ indicates the two lieux-dits sources, Les Chaillots and Les Hautes Vignes, where dual soil types—sables (Les Chaillots) and argiles légères (Les Hautes Vignes) bring their unique personalities to the wine. 100% Chardonnay from the 2019 vintage, vinified in oak barrels, and bottled using gravity, without filtration or fining and aged with cork and staple. Bottled in July 2020, tirage sur liège; disgorged January 2024 and dosed at 2.5 grams per liter. Clean and intense with warm, rich aromas of brioche and roasted almonds and on the palate, honey and minerals on a sustained finish.

Production: 2009 Bottles

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘C.H.V.’, 2016 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut 1.5 Liter ($247)

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘C.H.V.’, 2016 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Écueil Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut 1.5 Liter ($247)

2016 was a rollercoaster vintage, but drawing from the twin lieux-dits of Les Chaillots and Les Hautes Vignes, the House has put together a beautiful Champagne, here in Magnum. Unfiltered, unfined and malo blocked. 100% Chardonnay with nine months sur-lie, 40% in large oak casks. The wine was bottled in July, 2017 and disgorged in October, 2023 with a dosage of 2 grams per liter; it exhibits aromas of warm, freshly-baked bread, lemon oil, white flowers and hazelnuts.

Production: 50 magnums

Premier-Cru Duality: Villages Écueil and Les Mesneux

Les Mesneux is located just below the northwestern part of the Montagne de Reims slope just south of the Reims beltway and rail line. Unlike Pinot-heavy Écueil, Mesneux leans toward Meunier with about 60% of the 118 planted to this varietal; Pinot Noir makes up 33% with the rest Chardonnay. Mesneux terroir is clay-limestone and sandy-loam and produces wines that are known for their delicate precision and focused tension.

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘Millésime’, 2018 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier-Cru Écueil & Premier-Cru Les Mesneux Extra-Brut ($79)

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘Millésime’, 2018 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier-Cru Écueil & Premier-Cru Les Mesneux Extra-Brut ($79)

2018 was a legendary vintage in Champagne; this blend of Premier Cru villages show the prolonged summer heatwave in the concentrated aromatics of the nose. 60% Pinot Noir and 40% Chardonnay, the wine spent nine months on the less, 40% of it in 228 liter casks. It was bottled in July, 2019 and disgorged December 14, 2023 and dosed at 2 grams per liter. It displays the elegance and weight of the vintage with crisp fruitiness and spiced notes of cinnamon, licorice and pepper.

Production: 900 Bottles

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘Millésime’, 2013 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier-Cru Écueil & Premier-Cru Les Mesneux Extra-Brut ($173) 1.5 Liter

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘Millésime’, 2013 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier-Cru Écueil & Premier-Cru Les Mesneux Extra-Brut ($173) 1.5 Liter

Millésime, of course, is a Champagne term for vintage and indicates that 85% of the grapes came from that specific harvest. 47% Pinot Noir and 53% Chardonnay, 25% fermented in oak from the difficult, but ultimately redeemed 2013 vintage. The grapes had their origin in the estate’s vines in Écueil and Mesneux; the wine was bottled in March 2014 and disgorged in May, 2024 and dosed at 2.5 grams per liter. It shows fruity notes of apples and apricots along with fresh almonds and hazelnuts and hints of coriander seed to add a touch of complexity.

Production 296 magnums.

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘M.A.M.’, 2016 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier-Cru Écueil & Premier-Cru Les Mesneux Brut-Nature ($139)

Champagne Lacourte Godbillon ‘M.A.M.’, 2016 Petite Montagne-de-Reims Premier-Cru Écueil & Premier-Cru Les Mesneux Brut-Nature ($139)

100% Pinot Noir. The abbreviation ‘M.A.M’ signifies the double-barrel terroirs; the lieu-dit Mont Âme is distinguished by its chalky and calcareous soil, contributing to the minerality and Les Migerats, whose rich clay brings plumminess of the fruit into focus. From the 2016 harvest—a tricky vintage that was ultimately better for Pinot Noir than Chardonnay—which spent nine months on the lees. Bottled in July, 2017; disgorged on May 9, 2023 with zero dosage, finished with cork and staple. The wine shows sweet notes of plum tarts and ripe drupes with a refreshing and persistent roundness.

Production: 1834 Bottles, 30 Magnums.

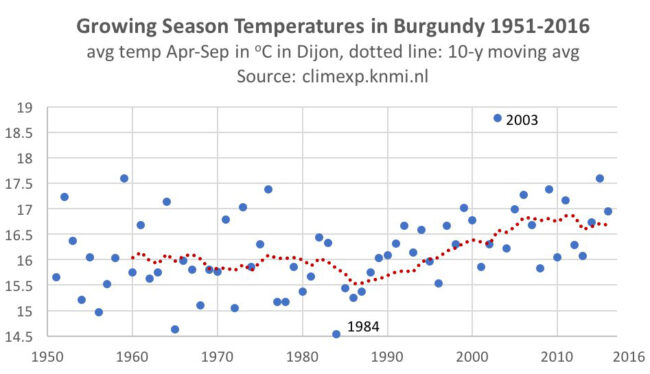

The New Reality: 2009 Indicates Champagne’s Paradigm Shift

Jean-Baptiste Lecaillon of Champagne Louis Roederer has been tracking climate change in Champagne since the year 2000. He reports, “Our archives covering harvests over the past 60 years show that since 1995 Champagne has returned to maturity levels which are, on average, in excess of 10 natural degrees of alcohol, with acidity levels around 7 to 8 gram/liter. These levels are close to those traditionally seen for great vintages including 1945, 1947 and 1959, but today’s yields are sometimes three to four times higher.”

Harvest dates in the vineyards of Champagne are among the marks used to measure climate change in general. Since 1989 (the end of a cool temperature cycle) harvest dates have crawled gradually backwards and the 2007 harvest started on August 20. By comparison, in 1945, the harvest commenced on September 8 and the 1947 harvest started on September 2, whilst harvests in the late 1980s were in early October. Harvest dates have grown earlier in each of recent years as means of controlling grape characteristics. Winemakers have been relying on newer techniques to obtain fresher wines as the raw material becomes riper. They are careful to manage malolactic fermentation, sometimes doing only partial MLF or halting it altogether.

Vintage 2009 represents the paradigm shift sweeping the region; in ways, a return to the golden years. It began with a cold winter, but a mild spring, and although early summer saw variable weather, August and September brought ample sunshine and warmth contributing to fine grape health. Harvest was pushed back until September 8, and the grapes, in general, displayed high sugar content and soft acidity. Potential alcohol crept up to 10.3% while acidity remained at 7.5 gram/liter at a pH of 3.08.

2009 produced a voluminous crop (12,280 kilogram/hectare) and the wines are generous that showed impressively even as vin clair. It is an apt example of a vintage of the current era, when retaining freshness is more of a challenge than attaining ripeness.

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

To be Champagne is to be an aristocrat. Your origins may be humble and your feet may be in the dirt; your hands are scarred from pruning and your back aches from moving barrels. But your head is always in the stars.

As such, the struggle to preserve its identity has been at the heart of Champagne’s self-confidence. Although the Champagne controlled designation of origin (AOC) wasn’t recognized until 1936, defense of the designation by its producers goes back much further. Since the first bubble burst in the first glass of sparkling wine in Hautvillers Abbey, producers in Champagne have maintained that their terroirs are unique to the region and any other wine that bears the name is a pretender to their effervescent throne.

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

The lauded wine writer Peter Liem expands the number of sub-regions from four to seven, dividing the Vallée de la Marne into the Grand Vallée and the Vallée de la Marne; adding the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay and combining the disparate zones between the heart of Champagne and Côte de Bar into a single sub-zone.

Courtesy of Wine Scholar Guild

Lying beyond even Liem’s overview is a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that compliment or contrast when final cuvées are created.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Épernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

… Yet another reason why this tiny slice of northern France, a mere 132 square miles, remains both elite and precious.

- - -

Posted on 2025.08.04 in France, The Champagne Society, Champagne | Read more...

Crossroads of Three Spains: Garnacha Finds Its Voice amid Gredos’ Ancient Granite Terraces as Vanguard Winemakers Lead a Revival

To understand Spanish wine in 2025, you have to keep up with it. Changes—good and less so—are inevitable, and the pace is increasing. Climate change is adding pressure to areas already rain-starved and some older wineries have simply allowed their once productive vineyards to all into disrepair.

This week, we turn our focus on one such region, Sierra de Gredos—still without its own appellation but a major personality all the same. Likewise, the winemakers. Having been largely ignored for decades, a new generation has been scouring the hillsides to find currently unused sources for the raw and rustic wines of the past century—Garnacha vines, most over fifty years old. In their dotage, these vines produce small, highly concentrated fruit.

The heavy-duty style of wine once the standard here has slipped out of fashion. Daniel Gómez Jiménez-Landi and Fernando García—Gredos natives and our featured producers—saw a niche that fit their philosophies of winemaking in general and Garnacha in particular. They are crafting Burgundian-style Garnachas—lighter, lower in alcohol and with considerably more finesse than most experts thought possible with the workhouse varietal. Their success can be gauged through the almost universal praise their bottlings have received, but it is best to discover this for yourself. For wines of this quality, prices remain extremely tame and will encourage a re-evaluation of Garnacha. Long the base of peasant wine, Dani and Fernando have released its innate nobility.

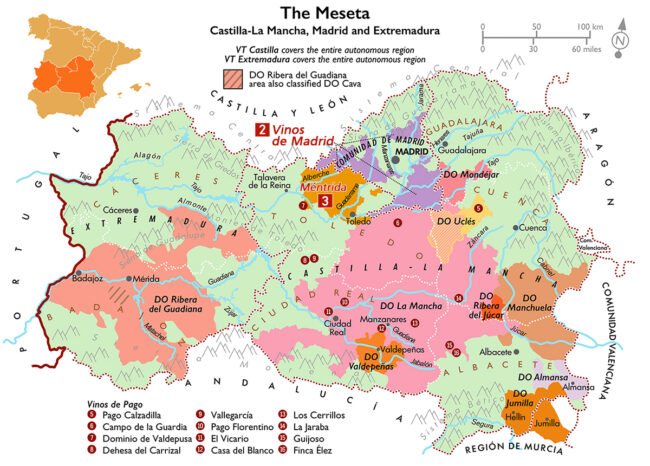

Gredos Reborn: Garnacha Bridges Three Spains

Gredos is a triumvirate—a triune kingdom spanning three glacial valleys (Alto Alberche, Alberche and Tiétar), three provinces (Ávila, Madrid, Toledo), three autonomous regions (Castilla-y-León, Madrid and Castilla-La Mancha) and three distinct appellations (Cebreros, Vinos de Madrid and Méntrida, along with the generic Vino de la Tierra). The mountains of Gredos soils, tradition and old bush vines, many neglected and awaiting re-discovery. The one thing it does not have? It is its own D.O.

This is hardly the result of laziness on the part of the Spanish, but the confounding paperwork of bureaucracy, which may be worse. Although conflicting interests have held back any movement in favor of an individual Gredos D.O., even labels that tout their legally-mandated appellations—Cebreros, Madrid or Méntrida—manage to worm ‘Gredos’ somewhere onto the bottle. And that is because these wines, pure, transparent and tense Garnachas and fresh, saline Albillo Reals, are among the most distinctive wines in Spain.

Preserving the Past, Cultivating the Future

Gredos enjoyed a brief revival in the 1970s, but the bulk of the past century threw slings and arrows at the region at every turn: Phylloxera arrived late, and then came civil war. When the railway from Valdepeñas to Madrid was built, it allowed an influx of wine into the capital, and Gredos found that its hard-to-work, often terraced vineyards could not compete.

For the bulk of the 20th century, Gredos descended into a vicious circle of low prices and diminishing demand.

If Gredos is currently sliding back under the microscope of wine lovers, it is because of the valiant efforts of new pioneers like Daniel Gómez Jiménez-Landi and Fernando García, who have set out to defined a new style of Garnacha—one that is light in color but intensely flavored, elegant and mineral-driven. The term ‘Burgundy-like’ is bandied about—a rare descriptor for Garnacha. The truth is, Burgundian or not, the red wines of Gredos have immediate appeal to those who grow weary with the heavy Grenaches of southwest France, especially as a summer refresher. Due to the elevations in Gredos (where even the lowest vines sit at over a thousand feet and the highest may top 4000) the wines are as crystalline and pristine as many top Pinot Noirs.

Viticultores Comando G

Granite. Guts. Garnacha.

If ‘Comando G’ sounds a little ‘thug’, it is: It originates in Spanish cartoon based on ‘Science Ninja Team Gatchaman,’ a Japanese anime series from the 1970s. Of course, for Daniel Gómez Jiménez-Landi and Fernando García, the twin ‘Gs’ (and true commandos) are Gredos and Garnacha.

And as the cartoon character saves the world from hostile forces, Dani and Fernando have made it their lives’ work to save endangered plots of granitic terroir in the Sierra de Gredos.

Friends since childhood, the pair returned home to the Sierra de Gredos after completing their education in enology: Dani landed at his family’s estate, Bodegas Jimenez-Landi, and Fernando at Bodega Marañones. Still, happy as they were to continue in the footsteps within the vats of their forefathers, they’d long heard rumors of small, nearly inaccessible vineyard plots located high in the Sierra de Gredos. Over time, they found and purchased the best of these old vine sites, and in 2008 founded Comando G under the conviction that in superior terroir and at high elevation, with the right handling, Spain’s workhorse Garnacha grape could produce to rival the elegance and finesse of Pinot in Burgundy or Syrah in the Northern Rhône.

Fernando García and Daniel Gómez Jiménez-Landi, Viticultores Comando G

According to Dani, “The development of Comando G was an organic process dictated by the conditions of each new parcel as it was added. Some, like Tumba del Rey Moro, Las Iruelas, and Rumbo al Norte, were what we considered Grand Cru sites from the first vintage, while others took time to recover and reveal their nature and character. Over time, Comando G coalesced around four villages in DO Cebreros—Rozas, Navatalgordo, Villanueva, and El Tiemblo. Each village is represented as a village wine or as a Premier or Grand Cru designations as warranted.”

Soil specialist Pedro Parra, with whom the partners work, describes the terroir: “The granite here is crumbly, even in the massive boulders with overhangs big enough to picnic under—you can pick it off with your fingers and break it into grains. As a result, the soil is coarse granite sand with perhaps 0.1% organic matter, and it can go down for ten feet before hitting stone. On the hilltops, though, it is so shallow that a plow will quickly hit bedrock. Around the town of El Tiemblo the granite gives way to schist, but it is also friable.”

How does that influence the wine? Fernando García says, “Schist produces complex wines with more assertiveness than granite. Schist wines are easier to understand while granite wines are more subtle. Granite gives direct, narrow, linear wines, while the amount of silt in the soil gives length. The silt also retains water better and gives balance in hot years. And there are, of course, different kinds of granite here. The brown granite gives complexity, white granite gives minerality and pink granite gives fruitiness. We have observed a correlation between the size of the quartz crystals in the granite and the tannins in the wine: The smaller the quartz crystals, the finer the tannins.”

The reputation of Comando G has grown over the past fifteen years; they are now considered among the most influential winemakers in Spain. In building their new winery, they first cleared the vineyard from all undergrowth, which uncovered many old walls and even abandoned vines that they are recovering and replanting in a titanic effort to restore the zone as it would have been many decades ago. This includes building new dry-stone walls and recovering old ones, and using stonemasons from Galicia to shape the local granite into building blocks for a winery that is fully integrated into the Gredos landscape.

Map by Quentin Sadler, Wine Scholar Guild

1 Cebreros: Redrawing Gredos’ Wine Map

As a legally demarcated PDO*, Cebreros is still damp behind the ears. Not officially recognized until 2019, the region has enjoyed a considerably longer period of notoriety—Cebreros wines have been popular in Madrid and Ávila since the 16th century.

Located in the southern section of the province of Ávila, which is itself located in southern section of the autonomous community of Castilla y León, the region covers 35 municipalities and includes a portion of the Sierra de Gredos mountain range as well as the valleys of the Alberche and the Tiétar Rivers. Although each valley has its own microclimate, in general, the altitude and rocky granitic soils have proven irresistible for high quality Garnacha, and in fact, half the vines in Cebreros are over sixty years old. Nearly 90% of the wine produced is red, with the legal standard requiring 95% of that be Garnacha. Still, the remaining 10% is an indigenous variety called Albillo Real, a grape which in warmer climates makes wine whose structure is linked to minerality more than acidity. In higher elevations such as Cebreros, where the lowest vineyards are 1600 feet above sea level, the sandier, granitic soils emphasize the acidity, making dense, age-worthy whites.

Currently, Cebreros has around 20 producers and fewer than a thousand acres under vine, making it ripe for discovery and one of the most prominent spots to explore new wave Spanish wines.

* As a note to lovers of wine minutia, the Vino de Calidad Indicación Geográfica of the European Union views the PDO classification as stepping stone to the more highly regarded ‘DO’ tier, for which a PDO becomes eligible after five years.

Viticultores Comando G ‘Navatalgordo’, 2023 Cebreros ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Alto Alberche’ ($61) Red

Viticultores Comando G ‘Navatalgordo’, 2023 Cebreros ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Alto Alberche’ ($61) Red

A village-level assembly of whole-cluster fruit from five unique lieux-dits scattered around Navatalgordo, where the Garnacha vines are, on average, 60 years old. The wine was allowed spontaneous fermentation on native yeasts, then aged in used foudres and concrete tanks for ten months and bottled without filtering or clarifying. It displays polished tannins behind delicate notes of strawberry, tart cherry and violet pastille, finishing with a pronounced mineral bite.

9,965 bottles made.

Viticultores Comando G ‘Villanueva’, 2023 Cebreros ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Alto Alberche’ (Villanueva de Ávila) ($61) Red

Viticultores Comando G ‘Villanueva’, 2023 Cebreros ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Alto Alberche’ (Villanueva de Ávila) ($61) Red

An old-vine Garnacha from Villanueva de Ávilait that could easily be mistaken for a Chambolle-Musigny; it displays a similar and distinctive freshness, finesse and elegance. It shows notes of ginseng, smoke and elderberries on the nose, while the mid-palate is chalky and herbal with vibrant acidity and a long finish that highlights its distinctly mineral character.

3,972 bottles produced.

Viticultores Comando G ‘La Bruja’, 2023 Cebreros ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Tiétar’ ($35) Red

Viticultores Comando G ‘La Bruja’, 2023 Cebreros ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Tiétar’ ($35) Red

La Bruja—‘the witch’—was formerly a village wine from Rozas de Puerto Real, but in 2023, the fruit was sourced from Ávila. As in the previous incarnation, the 2023 was hand-harvested, allowed a natural yeast fermentation and a long maceration followed by nine months in oak vats. The wine oozes with complex flavors of blackberries, bright watermelon, red flower petals, cracked black pepper and damp earth. It is expressive and driven, almost in the style of a Morgon.

56,487 bottles produced.

Map by Quentin Sadler, Wine Scholar Guild

2 Vinos de Madrid: At the Edge of Gredos

In the wake of the 1914 scourge of phylloxera, the vineyards that encompass what is today designated ‘Vinos de Madrid’ were a post-apocalyptic wasteland. In the Golden Age of the Spanish Empire, Vinos de Madrid encompassed more than 150,000 acres; in the rebuilding phase, which took place over the rest of the last century, about 22,000 acres were replanted with easier, higher-yielding varieties like Garnacha and Airén.

Today, the region—given official DO status in 1990—covers 55 communes and is divided into three unique subzones; Arganda, in the southwest and occupying the slopes that overlook the Jarama River, represents roughly half of the total VdM vineyards. It is planted with Tinto Fino for red and Malvar and Airén for white. Navalcarnero is a small area in the north of Arganda; it is built mainly in the highlands above the Guadarrama River. San Martín de Valdeiglesias is west of Navalcarnero; it is the smallest, the most spectacular and the most mountainous, being chillier and wetter than the other two zones.

Viticultores Comando G ‘Rozas’, 2023 Vinos de Madrid ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Tiétar’ (Rozas de Puerto Real) ($61) Red

Viticultores Comando G ‘Rozas’, 2023 Vinos de Madrid ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Tiétar’ (Rozas de Puerto Real) ($61) Red

Rozas originates from six vineyard plots totaling 15 acres of old-vine Garnacha located at the foot of Cerro de los Corzos. Rozas 1er Cru is Burgundian in style (hence its ‘Premier Cru’ designation), a lithe and winsome example of mountain Garnacha with deep minerality and firm tannin. Notes of strawberry and pomegranate brighten a powdery, chalky texture.

11,298 bottles produced.

Vitícola Mentridana

Deep Roots, Light Garnacha.

Curro Barreño may have earned his reputation in Ribeira Sacra with Fedellos, where he worked with indigenous grapes like Mencía, Mouratón and Bastardo, but he’s a Méntrida man at heart. So, when Dani Landi went in search of someone to take the reins at his vineyards in the Tiétar Valley while he founded the dynamic Comando G, Barreño was the logical choice. Already used to working formidable vinescapes (Ribeira Sacra is filled with steep, nearly vertical slopes and centuries-old terraced walls), Barreño added some family property into the mix and renamed the project Vitícola Mentridana.

Curro Barreño, Vitícola Mentridana

“Dani and I have been friends since childhood,” Barreño says, “and over the years, we’ve shared many bottles of wine and—more importantly, we have a similar outlook on winemaking. We both saw that Garnacha had a soul that could rise above the daily, simple fruity beverage consumed by Madrileños into a product of great depth and complexity. So when I took stewardship of Dani’s Méntrida vines in 2021, it was to build on a meticulous foundation, interpreting these vineyards through what I have learned, both here and in Galicia.”

Located at the point where Alberche changes course from flowing southeast to the southwest before it eventually joins the Tagus, this is a landscape of sandy, granitic soils, meadows, and holm oaks. As a result, Vitícola Mentridana is a more Mediterranean expression of the Gredos.

“What I am after,” Barreño explains, “is a wine that can remain light on its feet, yet still show the remarkable precision and depth of which Garnacha de Gredos is capable. This is achieved through whole-cluster fermentation and a short maceration of eight days followed by foudre-aging, allowing the ripe fruit to be supported by a mineral lift and delicate tannins.”

3 Méntrida: Gredos Bones in a La Mancha Body

Skirted by the Sierra de Gredos mountains to the northeast and subdivided by three rivers (the Alberche, Guadarrama and Tagus) Méntrida nonetheless has a water problem. Summers are relentlessly dry and compromisingly hot, regularly reaching 110°F and more, and if you are not directly on a waterway, the terrain is arid. They don’t call it ‘el sartén’—the frying pan—for nothing.

Such harsh conditions are not for wimps, and indeed, the winemakers willing to brave these challenges are a special breed. Although Méntrida was awarded DO status in 1976, major progress stalled as the region continued its long tradition of producing basic table wines aimed at local consumers. Sales shrank significantly during the 1980s, and has only recently begun to spring back into the limelight as modern producers with modern techniques and quality-focused mindsets have begun to dominate the vineyards. Garnacha is the favored grape and accounting for almost 80% of total production, producing robust, tannic and age-worthy wines. It is also used for rosé wines (rosado), known for their fruity and refreshing characters. Méntrida white wines definitely play second fiddle, although quality bottling are made from Albillo, Macabeo (Viura) Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay. Currently, there are 13,800 acres under vine.

Vitícola Mentridana ‘El Mentridano’, 2022 Méntrida ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Alberche’ (Pueblo de Méntrida) ($21) Red

Vitícola Mentridana ‘El Mentridano’, 2022 Méntrida ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Alberche’ (Pueblo de Méntrida) ($21) Red

An intense, high-altitude Garnacha, hand-harvest and whole-cluster fermented on native yeasts followed by an eight-day maceration and seven months in clusters, then aged for seven months in 30 and 37 hl French oak foudres. It shows notes of dark cherry, wild strawberry and a thyme-like herbal note on the finish. Valle del Alberche has a warmer climate than Gredos, allowing the grapes to ripen more fully; to avoid excess, the wine is given a shorter maceration period.

17,000 bottles produced.

Vitícola Mentridana ‘Las Uvas de la Ira’, 2022 Méntrida – ‘Sierra de Gredos’ (Pueblo el Real de San Vicente, Toledo) ($34) Red

Vitícola Mentridana ‘Las Uvas de la Ira’, 2022 Méntrida – ‘Sierra de Gredos’ (Pueblo el Real de San Vicente, Toledo) ($34) Red

‘Las Uvas’ is sourced from six lieux-dits in the village of El Real de San Vicente. Totaling 17 acres of Garnacha vines over 70 years old and planted on poor granitic soils at 2800 feet in elevation, the extreme environment has a significant variation in ripening times, so Uvas de la Ira sees several different harvest and maceration times that range from 30-60 days. Otherwise, hand-harvesting is a given, as is fermentation on indigenous yeast. The somewhat light-footed wine is fragrant with strawberry and garrigue and finishes with the crash of salinity.

Vitícola Mentridana ‘Cantos del Diablo’, 2021 Méntrida – ‘Sierra de Gredos’ (Pueblo el Real de San Vicente, Toledo) ($232) Red (1.5 Liter)

Vitícola Mentridana ‘Cantos del Diablo’, 2021 Méntrida – ‘Sierra de Gredos’ (Pueblo el Real de San Vicente, Toledo) ($232) Red (1.5 Liter)

Cantos del Diablo—the Songs of the Devil—is a tiny plot of 70-year-old vines near El Real de San Vicente in Méntrida. A combination of sparsely planted vines, exposure, climate and the age of the vines results in low yields. It’s also a cool site that ripens late and produces ethereal Garnacha typical of Garnacha’s profile when grown on sandy granite. Hand harvested, whole cluster natural yeast fermentation, pigéage and allowed a 75-day maceration. The wine is racy and taut, filled with red fruits and damp stone notes with touches of herbs and spice throughout.

A Pie de Tierra

Gredos’ New Guard, Next-Gen Garnacha

Dani Landi and Fernando Garcia’s influence in contemporary Gredos cannot be overstated, and among the generation who have learned from them, and who have now begun to put their own stamp on the granitic terroirs of the region, no one stands out like Aitor Paul and David Villamiel. Having met at enology school in 2015, the pair interned at Bodegas Valquejigoso and Comando G. With their own theoretical knowledge about vineyards and insight into the rapidly changing practice of wine growing in Spain, they began to work fifty acres owned by David’s parents—Gredos growers in the Alberche valley for many years.

Aitor Paul and David Villamiel, A Pie de Tierra

Says David, “All this Garnacha is either old, head-pruned vines or younger vines grafted onto ancient rootstock, and all was planted long before the Gredos was recognized for the quality of its Garnacha. We farm a range of Garnacha biotypes—an ancestral inheritance of the most suitable Massale-selections.”

Of technique, Aitor Paul adds, “We approach winemaking as we observed at Comando G. That means gentle macerations that are suited to the internal classification system we’ve devised: 25 days for our village-level wine, El Surco, while Fuerza Bruta sees up to 60 days on its skins before pressing. Fermentations are spontaneous and range from 70-100% whole cluster. We only employ used French oak barrels or vats made from French oak or Galician chestnut for aging.”

A Pie de Tierra ‘Pueblo El Surco’, 2022 Méntrida ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Alberche’ ($21) Red

A Pie de Tierra ‘Pueblo El Surco’, 2022 Méntrida ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Alberche’ ($21) Red

Thanks to a trademark issue, the village level ‘A Dos Manos’ is called ‘El Surco’ (The Groove—a reference to both the furrows left by a plow and the new-wave style) in the United States. Built from 40-year-old Garnacha vines grown at elevations in excess of 2000 feet, the grapes are hand-harvested, 70% whole-cluster fermented on natural yeast and given a 25-day maceration regimen before spending a year in seasoned French oak. The wine shows delicate aromas of summer strawberries, bramble, rose petals and soft spices.

A Pie de Tierra ‘Paraje Fuerza Bruta’, 2022 Vinos de Madrid ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Alberche’ (Dehesa de Navayuncosa) ($29) Red

A Pie de Tierra ‘Paraje Fuerza Bruta’, 2022 Vinos de Madrid ‘Sierra de Gredos – Valle del Alberche’ (Dehesa de Navayuncosa) ($29) Red

A portrait of authenticity and a paean to the rugged landscape from which it emerges, Fuerza Bruta—’Brute Force’—hails from Aldea del Fresno vineyards. Crafted from 60-year-old Garnacha vines grown organically in granite alluviums, it is 100% whole-cluster fermented on indigenous yeasts, and sees 45 days of maceration before spending a year in large chestnut barrels and French oak foudres. The wine undergoes malolactic fermentation without clarifying or filtering. The wine is light, elegant and almost Rhône-like; it shows pretty highlights of spring berries, anise and watermelon candy.

Northwest, Along the Duero River

Toro & Arribes

From Gredos, we move a few dozen miles up the Duero River, heading northwest to Toro, where we find a similar dedication to upgrading the reputation of the native grapes. In this case, Alvar de Dios—also a student of Dani Landi and Fernando Garcia—has approached Tempranillo with the same reverence as Dani and Fernando did with Garnacha, and unearthed a similar finesse. He also works with a number of varieties unique to Toro, some of which have yet to be identified.

This selection of wines is a fine representation not only of the direction that Toro is taking, but of the personalities of the winemakers who are taking it there.

Alvar de Dios

Elevating Forgotten Vines at Spain’s Western Edge

It’s a tangled path to glory, and Alvar de Dios has paved it with dedication. Having been born to a vineyard-tending family in El Pego, near the southern boundary of DO Toro, he opted to learn winemaking outside of his native village, finding inspiration in the rebel yell of Dani Landi and Fernando Garcia. While working as cellar master for Fernando at Bodega Marañones, he began acquiring vineyards of his own in his old neighborhood, finding it possible to split his time the Gredos and Toro.

His first chunk of property was inherited; ‘Aciano,’ named for grandfather, totals eight acres of extremely old Tempranillo at an elevation over 2000 feet. Planted in sandy soils in 1919, these vines proved resistant to the phylloxera scourge of the 1920s. He began to tend the vines organically, and although he was gifted the vineyard in 2008, he waited until the vines had suitable time to respond to his care, waiting until 2011 to make his first vintage.

Having purchased an additional acre-sized plot of abandoned vines called Vagüera just south of the legal border of Toro. He was awed by the elevation (3100 feet), but more so by the terroir.

Alvar de Dios

He says, “Vagüera is fascinating terroir, unique to the area, shallow rocky red clay soil over limestone, north-facing, and sheltered by a cork oak forest. It hasn’t been tended since 2006 and has a bewildering mix of white varieties. So far I have identified Doña Blanca, Albillo Rojo, Albillo Real, Albillo Negro, Albillo Castellano, Moscatel de Grano Menudo, Muscat de Alexandria, Moscatel Rojo, Godello, Verdejo, Palomino Fino, and Malvasia! There are at least another more that I cannot yet name. Records indicate that this vineyard was planted in 1921.”

Alvar next set his sights on Arribes, a new DO that only gained status in 2007. The valley is the point where the Duero River becomes the Douro as it leaves the steep granitic mountains that form the border between Spain and Portugal and where the soils reminded him of Gredos. Rather than Garnacha, however, he found a range of indigenous varieties capable of expressing the elegance and freshness that he so loved in Gredos.

In Arribes, he has assembled twelve acres from 36 separate vineyard parcels between the towns of Villadepera and Fermoselle (a.k.a. Zamora). He says, “Camino de los Arrieros is my village wine, made from 40-60-year-old vines of Juan Garcia, Rufete Trincadeira Preta, Bastardo, as well as some other unidentified varieties. I’ve also managed to identify two tiny, enclosed vineyards near Villadepera—Las Vidres planted with Doña Blanca and Yavallo planted with Merenzao Rufete, Trincadeira Preta, Méncia, and Doña Blanca. Both vineyards are 80-90 years old. Las Vidres shows a profoundly mineral core with evocative aromas of wild herbs and pollen, while Yavallo is fresh and floral with a depth of flavor and precision that seem to be like a cross between the Jura and a top Douro red.”

1 Toro: Muscular Red, Refined on Castilla’s High Plateau

Even the name suggests untamed intensity and brute strength. In fact, throughout most of its history, the region was a Spanish backwater producing harsh, strong reds intended largely for local consumption. Aggressive alcohol and muscular tannins ensured that the region was hard-pressed to build an audience outside its borders.

But like many similar, rustic areas in Spain, formerly written-off by high-brow consumers, a new generation is re-evaluating varieties and terroirs throughout Toro, and finding a ripe ground for investment and better viticultural management. The wines are primarily red and made from Tempranillo (here called Tinta da Toro) with a longer vegetative cycle that helps it cope with the heat. Altitude also plays an important role in Toro’s terroir. Situated on the vast, high plateau that separates the Cordillera Cantábrica and Sistema Central mountain ranges, most vineyards sit at altitudes between 2000 and 2800 feet.

Alvar de Dios ‘Parcela Aciano’, 2020 Castilla-y-León ‘Toro’ (Village El Pego) ($33) Red

Alvar de Dios ‘Parcela Aciano’, 2020 Castilla-y-León ‘Toro’ (Village El Pego) ($33) Red

Aciano comes from a ten-acre, pre-phylloxera vineyard once owned by Alvar’s grandfather. It is predominantly planted with ungrafted Tinta de Toro more than a century old. Winemaking is traditional, fermenting on native yeasts aging in used oak barrels. The wine brims with wild bramble-berries, hints of violet perfume and garrigue, finishing with sandy tannins enveloped in minerality and nuances of aromatic herbs.

Alvar de Dios ‘Parcela Vagüera’, 2021 Castilla-y-León ‘Toro’ (Village El Maderal) ($42) White

Alvar de Dios ‘Parcela Vagüera’, 2021 Castilla-y-León ‘Toro’ (Village El Maderal) ($42) White

Within the three-acre Vagüera vineyard there are only 300 vines, yet they represent 15 different varieties of white grapes including Verdejo, Godello and Albillo. Doña Blanca comes from a single plot in El Maderal, which is the highest municipality in the Guareña region—an elevation of over 2000 feet gives the area a distinct Atlantic character. The soil here is clay, not sand, which helps retain moisture when it rains. These vines were planted in 1920; they are harvested by hand, give a short cold maceration of under a day followed by a gentle pressing. Fermentation takes place in used 300-liter barrels on native yeasts. It rests for a year before bottling without filtering or clarifying. The wine sports a well-defined bouquet of citrus and apricot and a creamy palate with a soft effervescence and a touch of minerality on the finish.

2 Arribes: Castilla’s Wild West

The Duero runs through many landscapes, but few are as dramatic and scenic as those on the border near Portugal—the steep gorges known locally as ‘arribes,’ which lend their name to one of the smallest and most remote DOs in Spain. Wine has traditionally been the area’s most well-known product, but in recent years—as in many outlying Spanish wine zones—the loss of vineyards has been staggering. In the 1970s, Spain’s Ministry of Agriculture estimated that 7000 acres in Fermoselle were under vine and another 12,000 acres in the Salamanca region of Ribera. Today, there are fewer than 700 vineyard acres registered in the whole appellation.

Terroir is the defining feature that set Arribes apart from the eastern side of the Duero valley. As it enters the gorges, the river is embedded in a Paleozoic basement composed of granite rocks and, to a lesser extent, slate. In general, granite is more prevalent in Zamora (it is not uncommon to find large rocks and boulders, like those of Gredos), while slate is mostly seen in Salamanca.

Alvar de Dios ‘Camino de los Arrieros’, 2020 Castilla-y-León ‘Arribes’ (Village Villadepera) ($24) Red

Alvar de Dios ‘Camino de los Arrieros’, 2020 Castilla-y-León ‘Arribes’ (Village Villadepera) ($24) Red

A field blend of Rufete, Juan García, Trincadeira Preta, Merenzao, Mandón (and other nameless varieties) whose vine-ages range between 40 and one hundred years and planted on sandy red slate soils. The wine is fermented whole-cluster by indigenous yeasts in 1000 liter French oak vats with old-school pigéage… by foot. The wine is complex and evolving, revealing aromas of black cherry, fig, and cedar and a pronounced mineral backbone.

Alvar de Dios ‘Parcela Yavallo’, 2020 Castilla-y-León ‘Arribes’ (Village Villadepera) ($69) Red

Alvar de Dios ‘Parcela Yavallo’, 2020 Castilla-y-León ‘Arribes’ (Village Villadepera) ($69) Red

Although smaller than half an acre, the Yavallo parcel features a staggering array of grape varieties, each of which find a home in this blend. 60% Merenzao, Yavallo also contains Rufete, Juan García, Trincadeira Preta, Mencía, Cariñena and about 5% Doña Blanca; all are old vines grown on sandy red schist soils. Harvested by hand in a single day, Yavallo is fermented whole-cluster on indigenous yeasts after a five day cold maceration. Fermentation and subsequent maceration last 40 days followed by aging for 12 months in a single 300L French oak barrel. The nose is a lure of wild strawberries and pomegranate accented by white pepper, sesame and wet gravel on the finish.

Alvar de Dios ‘Parcela Las Vidres’, 2020 Castilla-y-León ‘Arribes’ (Village Villadepera) ($69) White

Alvar de Dios ‘Parcela Las Vidres’, 2020 Castilla-y-León ‘Arribes’ (Village Villadepera) ($69) White

Las Vidres is an enclosed, acre-sized vineyard in Villadepera just a few miles from the border of Portugal and is planted to 80-90-year-old Doña Blanca. It enjoys gentle, southeasterly exposure and sandy, volcanic soils that produces scarcely more than a couple barrels of wine per year. In a style reminiscent of an age-worthy Pouilly Fumé, Las Vidres shows damp stone and fig on the nose with gunflint, white pepper and a saline finish.

Bodega Almaroja

Pioneering Biodynamic Reds in Rugged Borderlands

‘Almaroja’ means ‘red soul’ and winemaker Charlotte Allen, a British ex-pat living in Spain, says, “Red symbolizes vitality, courage, optimism, nonconformity and passion.”

All of these attributes are integral to the soul of this iconoclastic woman and her deep love for the rugged terroirs of Zamora. She operates (for the most part) alone, adhering to the best of biodynamic practices, working on weaker parcels on specific dates and times, treating her vineyard for pest with botanical blends, including sage and nettle. She hand-harvests a scant half-ton per acre and grows a number of spectacular grapes little known outside her region.

Long a friend of Elie’s, Charlotte wrote us in 2019 and offered us some background notes:

“When I moved to Spain in 2007 and started making my own wine, I had a very clear vision of what I wanted to do, which was to make just one barrel-aged red wine. This first wine was named Pirita Crianza. For a couple of years that was enough, but slowly I felt the need to challenge my skills, so along came a white, also under the Pirita label, and then a top cuvée, Charlotte Allen. For a few years I was happy with just these three wines, but by the time 2015 came along, the old wanderlust was back.

Charlotte Allen, Bodega Almaroja

“Cielos y Besos was born on a long car journey to the mountains. With my son sleeping in the back seat, I started to think about a particular tank of wine I had which was bright, fresh and fruity and just said ‘Drink me.’ I had never before thought of making a ‘joven’—that is to say a red wine with no barrel aging, but as the miles sped by and the mountains approached, it seemed like an increasingly good idea. So good in fact, that by the time we arrived at the ski station, the decision had been made.

“The name was inspired by one of my favorite songs, ‘Tiempo y Silencio’ by the Cape Verde singer Cesária Évora. I had always thought that the title of song (Time and Silence) would be a wonderful name for a wine. There is however a much bigger bodega in Extremadura which makes a wine called “Habla del Silencio” and I knew that a court case would probably leave me with nothing more than lawyer’s fees and egg on my face, so gave up on the idea. But the song just kept going around in my head. “Tiempo y silence, gritos y cantos, cielos y besos, voz y quebranto…” The name seemed somehow joyful to me, much like the feeling the wine inspired.

“It is a blend made up predominantly of organically-farmed old vine Juan García, a variety native to the Arribes del Duero and the most widely planted red grape in the area. The wines of this variety are characterized by wild berry fruit, fine tannins and good acidity. The remainder is an eclectic mix of Tempranillo, Rufete, Bastardillo Chico, Bastardillo Serrano and Garnacha, with a few kilos of white grapes thrown in for good measure.

The grapes were fermented in concrete tanks at a relatively low temperature of 77 degrees Fahrenheit. The wine spent around three weeks on the skins, with a daily pumping over. It was older in these same tanks for around eight months and was bottled without fining or filtration and with no added sulfur. I recommend drinking it very slightly chilled.”

Bodega Almaroja ‘Cielos y Besos’, 2022 Arribes ($22) Red

Bodega Almaroja ‘Cielos y Besos’, 2022 Arribes ($22) Red

A blend of Juan García, indigenous to Arribes del Duero, Bruñal (another variety indigenous grape) and Rufete, is a native of Portugal. The wine spends four days in a pre-fermentation maceration, followed by a fermentation on the skins for almost three weeks in temperature controlled concrete tanks, and with a pump-over once every two days. The wine then spends eight months on its fine lees in concrete tanks, and undergoes full malolactic fermentation before being bottled without fining, filtration or stabilization. The wine is intense with dark plum and smoke notes.

2019 Bodega Almaroja ‘Pirita’, 2019 Arribes ($33) Red

2019 Bodega Almaroja ‘Pirita’, 2019 Arribes ($33) Red

Another explosive showcase for the local varieties Juan Garcia, Rufete and Bruñal, the Pirata name references pyrite, the ‘fool’s gold’ of the mineral world. Like Cielos y Besos’, the grapes for Pirita undergo a pre-fermentation maceration in a blend of temperature controlled stainless steel and concrete tanks, followed by a fermentation of four weeks with daily pumping over. Pirita then spends a year in 300-liter French oak barrels, where it undergoes malolactic fermentation before being bottled without filtration or stabilization, but some clarification. It shows notes of roasted plum, cranberry, earthy blueberry and a solid acidic core.

- - -

Posted on 2025.07.29 in La Tierra de Castilla, Spain DO, Wine-Aid Packages, Arribes | Read more...

The Future of Burgundy Lies in Lesser-Known Areas: Boris Champy Believes Elevation, Vineyard Orientation and Clonal Selection Hold Some of the Answers to Climate Adaptation. * Mixed 5-Pack (3 Red, 2 White) – $389

“The best fertilizer is the winemaker’s shadow.”

Nowhere does this aphorism hold truer than in Nantoux, Burgundy, where Boris Champy carries on an endless quest to reveal the soul of each vineyard plot, the spirit of each grape variety and the essence of place inherent in every glass of wine. Having purchased the estate from Didier Montchovet—one of the biodynamic pioneers in France who were practicing eco-friendly, solidarity-driven viticulture before the word became fashionable—Champy took over with the intention of using global warming as an advantage in lesser-known mountainside vineyards.

This week’s 5-bottle sampler package ($389) reflects both the philosophy and the product: Stellar examples of Burgundy’s new visage. Boris Champy has awoken long overlooked terroirs to produce wines with cellar-aging potential as well as immediate enjoyment—a work-in-progress that Champy describes as being ‘the result of patience and foresight; a path that respects man in his environment.”

The Future of Burgundy: A Region Reckons with a Changing Climate

April, 2021 has been called the worst month ever for French vineyards: Severe spring frosts created crop losses estimated at 80 to 90% in some areas. These chilly announcements from the planet at large are but a single symptom among the host of challenges that climate change is bringing to the region.

Burgundy’s reputation for elegant wines is inextricably linked to its cool northerly climate. When summer temperatures remain consistently above normal, grapes ripen more rapidly and are at risk of losing the delicacy that translates into finesse when vinified, and although there is certainly a place for bigger, fatter, bolder Chardonnays and Pinot Noirs, this market has been saturated in the past few decades with wine from warmer, flatter regions in the New World, and, in fact, bucks current consumer trends.

Burgundy’s winemakers are not without options, of course, having at their fingertips an array of viticultural and winemaking tools to mitigate the damage. But as 2021’s frost proves, such methods are not fool-proof and more drastic action will likely follow, from restructuring the Cru system to exploring the potential of other grape varieties. Burgundy has placed nearly all of its varietal eggs in two baskets, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, and upsetting this particular apple cart is not an easy decision for an area tied to tradition. But along with finding new terroirs in regions previously unsuited for viticulture—higher elevations, for example—they may represent not merely the best routes, but the only ones.

The 2020 Vintage: A Historic Early Harvest, Not Seen in Over 450 Years

The term ‘ban des vendanges’ may not be familiar outside Beaune, but it represents the earliest date on which harvests have been allowed to start. Pick earlier and you might forfeit your entire crop—‘ban des vendanges’ was a form of quality control that ensured the grapes were not harvested unripe. After 2006, following the ‘ban’ was no longer mandatory became a symbolic date, set much earlier than is practical for harvesting. Historically, this date has been a consensus between vine-growers and local town administrators and also considers the availability of harvest labor coming from outside of the town and even the potential for military threats or outbreaks of plague.

And with Covid in full swing, that sounds like 2020, when the harvest began on August 14, fully two days earlier than the record set in 1556, August 16.

The 2021 Vintage: Unyielding Challenges, Exceptionally Small Crop

2021 began as a dream vintage. The previous winter was relatively mild and copious amounts of rain replenished the water tables, so to winemakers, a season of extreme heat (as has become the norm) could be faced with confidence. March began with a cooling trend, but then warmed up and became almost summery, allowing the vegetative state of the vines to progress well. Then came April 5 and a devastating frost with temperatures below 20°F, effectively decimating the Chardonnay crop and putting the skids on Pinot Noir. The rest of the season progressed somewhat normally, but the vines were not able to recover entirely from the frost damage and yields were much lower than was initially hoped for.

The wines, however, made up for in quality what they lacked in volume, presenting a classic maturity index with correct sugar content and a nice acid balance. In many cases, success was measured by the skill of the viticulturist, who needed to monitor the health of each plot, treat for mildew and harvest at aromatic maturity.

Raising Burgundy

Domaine Boris Champy

An Eco-conscious Producer Bets on Biodiversity and Altitude

Boris Champy is to the Hautes-Côtes what ‘imagineers’ are to Disney—seers of the future. With the steady march of global warming, Champy recognizes that mountain vineyards will become more temperate in the decades ahead, and his vineyards are well suited to raise the reputation of the entire appellation. With more consistent ripening, Champy’s objective is simple: To show the subtle differences between the climats and terroirs to which he has access via soil types, sun exposures and slope inclinations.

To this cornucopia of promise, Champy brings an organic mindset: “We practice a viticulture respecting nature. Our single plot vineyards are large biodiversity islets where a holistic approach is required; a global ecosystem with regenerative farming and utter respect for the environment.”

Boris Champy – Domaine Boris Champy

Champy began his oenology career on near-hallowed Napa ground, remaining with the Dominus Estate for a decade. He later became technical director for a well-known négociant in Beaune, and then estate manager for the famous Clos des Lambrays in Morey-Saint-Denis. He was also president of the Corton ODG and responsible for the creation of an environmental protection association.

“My goal from the beginning has been to showcase the lieux-dits of the high-lying hills and valleys of the Hautes-Côtes, and to highlight the different microclimates, exposures and other fascinating subtleties,” Champy says. “As a means to this end we practice viticulture that is still somewhat alien to the great winegrowing Côte. Our vineyard plots are small islands of biodiversity with numerous quickset hedges, meurgers (thick stone walls) and fruit trees. This is a philosophy of regenerative agriculture.”

Regenerative Agriculture: A Living Tapestry of Soil, Fauna and Flora

In recent years, the term ‘regenerative agriculture’ has replaced ‘sustainable’ in the lexicon of ecology, at least as a consummation more devoutly to be wished. Sustainable farming is a harm-reduction approach—a crucial first step on the path toward creating an overall system that actually adds to nature’s richness. A farmer can begin by reducing external inputs like pesticides, for example, and eventually enhance the health of the land so much that chemicals aren’t needed at all. When measures to enrich the land—such as planting shade trees to protect and nourish soils—are applied on all fronts, you may lay claim to being a regenerative farm.

Boris Champy is a cheerleader for this method: “At the domain we believe entirely in this concept of agriculture: Our hedges are a habitat and a source of food for wildlife. Birds will feed on the seeds of plants growing amid the vines. Birds of prey will feed on small birds and mammals. Hazel trees, brambles and hawthorns have a positive impact on the soil. Mycorrhizae, fungus networks and other microorganisms will help build the strength of the vines that in turn will be transmitted to our grapes.”

Animals and non-vine flora are his partners in the approach, and he points to hedges and thickets with thick dry-stone walls that provide a perfect habitat for birds, lizards and fertile ground for orchids. “We showcase the domain’s history in the plants we encourage; black pines, Scots pines, sorb trees. Each of these trees bears witness to our domain’s past: wood from the sorb tree was used to make the screw of the wine presses; the black pine was planted after Phylloxera. We also allow dead trees to decompose to encourage biodiversity.”

Biodiversity: Where the Vineyard Is a Garden with Sheep, Chickens, and a Dog Named Napa

The age-old farming paradigm, still prevalent, is changing: Time was, agricultural wisdom called for one or two species of forages and grazed by a single species. In France, as in the Midwest of the United States, this is generally what you still see: Closely grazed pasture with leggy tufts of mature stalks from less-palatable plants bringing selection pressure to bear in causing the eventual demise of the best forages.

Boris Champy and Napa – Domaine Boris Champy

Boris is a trendsetter: “We like to use the green manuring technique: in summer we sow vetch, rye, fava beans, mustard, Chinese radish and peas between the rows. These plants offer many benefits: they improve soil fertility, provide nitrogen and support microbial life. They are also bee-friendly, to the delight of the local beekeeper! We are bringing grazing back into fashion with a flock of sheep that gives our vineyards a thorough natural mowing. Our flock is made up of Thone and Marthod sheep, a breed from the Alps, which is very docile and accustomed to our Border collie, named ‘Napa’. Napa is very useful on the farm, especially for rounding up the sheep and moving them from one plot to another during the grazing periods. Thanks to our friend Fred Ménager from the Ferme de la Ruchotte, we have also adopted some specimens of old breeds of hen: Gauloises Dorées, Gauloises Grises, Faverolles, Le Mans and Marans.”

The Reawakening of Terroir Through Natural Viticulture and Winemaking

Boris Champy thinks about the past nearly as much he considers the future. He says, “Over my career, I have had the opportunity to participate in exceptional vertical tastings of Côte de Beaune and Côte de Nuits wines. Each time, I have come to the same conclusion, that authentic wines from the years 1910 to 1950 have stood the test of time. They are excellent wines with fruit and complexity which are still a pleasure to drink. From the 1960s onwards, the quality becomes inconsistent, the wines are often dull, boring or sometimes dead due to intensive viticulture (chemical fertilizers, weed killers, synthetic chemistry, clonal selection, etc.). From the 1990s onwards, the quality of the wines returns. Some have called this the ‘awakening of the terroirs.’ Our decision to use natural viticulture and winemaking has the single but ambitious objective of producing wines with cellar-aging potential that have taste and are enjoyable to drink.”

Whole Bunches, Whole Philosophy

In another nod to history, Boris Champy explains his passion for using a high proportion of whole bunches of grapes by reminding us how recently the destemmer machine came to the wine cellar. “Like every invention,” he says, “it has both positives and negatives. Destemming has led to higher yields (with grapes that are not necessarily very ripe), and the planting of certain clones that produce large bunches of grapes whose stalks are unable to ripen. The return to the use of whole bunches is a rejection of these industrial techniques: viticulture with lower yields, the abandonment of high-production clones, the pursuit of perfect maturity and vinification by plot.”

This, he believes, is borne out by tasting and analyzing old vintages. “When we consider very old wines, and specifically, certain tannins derived from the stalks, we can conclude that, in the 1910s and 1920s, the very great Burgundy wines were made from whole bunches of grapes. We are still learning about these stalk tannins: They have a ‘sweet’ taste, a characteristic typicity that can be found in the very great wines produced today using whole bunches by the world’s greatest estates (DRC, Leroy, Dujac, Gonon, Chave, etc.).”

Above the Côte

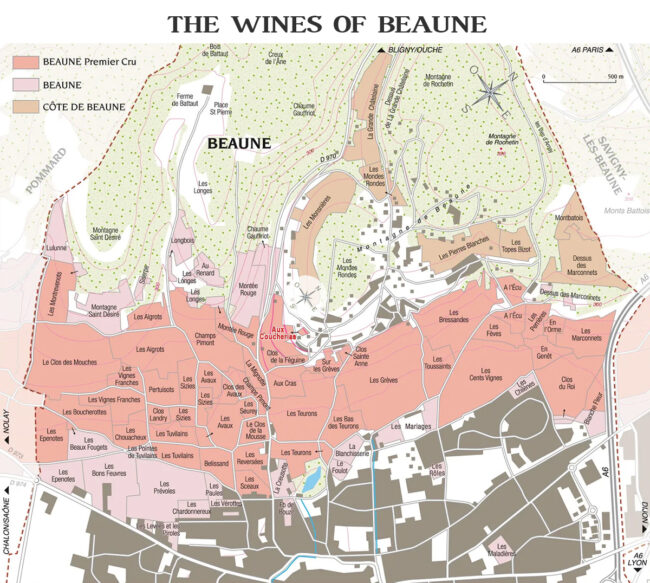

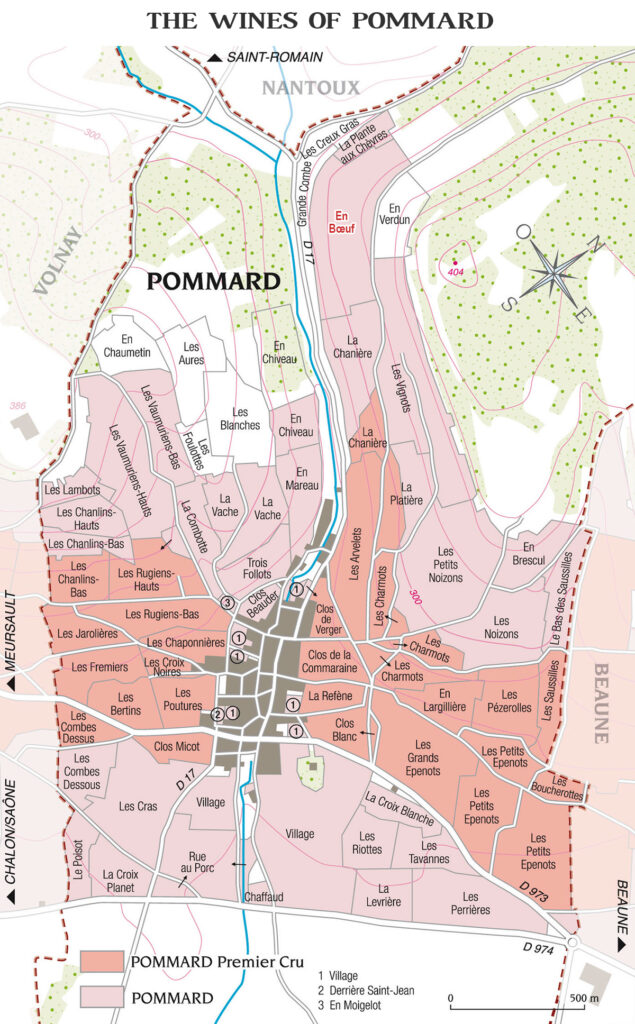

The Revival of Beaune’s High Slopes

Before the phylloxera plague of the nineteenth century, vines grown on the sunny, limestone cliffs along a ribbon of valleys perpendicular to the Côte de Beaune from Les Maranges to Ladoix-Serrigny were a famous source for Chardonnay and Pinot Noir; these were the wines that were ordered to celebrate the coronation of Philippe Auguste in 1180. Post-phylloxera, between 1910 and 1936, almost half of the Hautes-Côtes de Beaune vineyard disappeared.

The region’s renaissance began with reestablishment of the winegrowers union of the Hautes Côtes de Beaune in 1945, which led to the creation of the appellation on 4 August 1961. The terroir is largely built around formations laid down 80 million years ago during the Triassic (sandstone and clay) and the Jurassic (marl and limestone) eras. The favored sites are on south and southeast-facing slopes of valleys cut into the limestone plateaus at between 900 and 1500 feet; considerably higher than the Côte de Beaune, which results in later maturing grapes and harvesting, on average, around one week later.

Boris Champy labels his wines according to the elevation of the vineyards; hence, Cloud 377 indicates, in meters, how high up the slope this plot of grapes grows.

1 Domaine Boris Champy ‘Clou 377’, 2020 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Beaune ($66) Red

1 Domaine Boris Champy ‘Clou 377’, 2020 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Beaune ($66) Red

Au Clou is plot of Pinot Noir that sits at 377 meters altitude (1237 feet) where the soils are white and stony with a high marl content—similar to the terroir of Châteauneuf-du-Pape. The vines are planted in traditional high-density style, with 10,000 vines/hactare using Guyot cane pruning. Grapes are hand-harvested at optimum ripeness and vinified using soft extraction with a large proportion of whole clusters used in wooden fermenters, followed by barrel aging for one year using an average of 30% new oak. The wine is perfumed with raspberries and violets, with silky black and red berries on the palate peppered with black tea and allspice.

2 Domaine Boris Champy ‘Montagne 388’, 2020 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Beaune ($56) White

2 Domaine Boris Champy ‘Montagne 388’, 2020 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Beaune ($56) White

388 meters = 1273 feet; Montagne de Cras is a 10-acre lieu-dit made up of vines abutting natural areas of biodiversity; scree slopes, hedges, orchards, limestone grasslands with numerous orchids and even a few rare corm trees, whose wood was once used to make screws for grape presses. Vinification takes place in 228-liter oak barrels (15% new) and, in part, in small round stainless-steel vats. This 100% Chardonnay is the antithesis of fat, oaky Chardonnays, showcasing instead a racy and bright style with lovely aromas of lemon, almond, stone, spiced pear and apple.

Aligoté on the Edge: Burgundy’s Other White Thrives in the Hills

“Aligoté!” sounds like a cry of triumph; something you’d shout after making a goal in the World Cup. In fact, perennially overshadowed by its sexier cousin Chardonnay and even its half-sister Pinot Gris (they share a father, Pinot Noir), there was a time when the opposite was true:

“Before phylloxera,” says Jérôme Castagnier, proprietor of Domaine Castagnier in Morey-Saint-Denis, “Aligoté was planted everywhere, literally. But after the outbreak abated, thanks primarily to American root stock, French growers took stock and realized that Chardonnay and Pinot Noir commanded higher market prices, so that’s what was re-planted. In fact, in some regions, Aligoté was banned altogether.”

Post-phylloxera Aligoté exists under the basic Bourgogne Aligoté appellation established in 1937 and, for the most part, produces inexpensive and simple wines, especially when planted in the less-valued soils of the Saône Valley flatlands. But true Aligoté fans, including Les Aligoteurs (a group of French producers and wine lovers who promote Burgundy’s all-but-forgotten white grape variety) believe that the grape better expresses the terroir of thinner, rockier, hillside soils. A cross between Pinot Noir and the ancient white varietal Gouais Blanc, Aligoté’s profile includes descriptors ranging from fruit-driven and floral to herbal and sharp with acidity. In either case, it is the essential base for the classic cocktail Kir when blended with Cassis.