Rosés Deserve To Live A Little: 2021 Rosés in Full Bloom, Show Character And Dimensions With Two Years of Maturity … 13-Bottle Pack $299 (Limited)

Any remaining stigma attached to rosé remains within the dark soul of the stigmatized; those of us on the right side of wine appreciation understand that rosé is enjoying the fruits—quite literally—of its historical labor. This is especially true in France, where the past several decades have seen rosé coming into its own.

Since 2000, white wine sales in France have plateaued while rosé’s have doubled; over that same timespan, red wine has declined in popularity at such a staggering rate that even if rosé does not win over a single new fan, it may well surpass red wine sales in France in the future.

As a springboard to spring, we will offer a fresh look at this old style through a series of French rosés that span the country from north to south in a 13-bottle package for $299.

Start With Red Grapes

Of the five thousand or so red wine grapes on the planet, the number that are unsuitable for making rosé is precisely zero. And yet, in France, more than 40% of rosé production comes from Provence—an appellation that alone accounts for more than 5% of rosé production worldwide. And in Provence, wine production is dominated by four grapes: Cinsault, Grenache, Mourvèdre and Syrah. The other rosé-producing appellations (as can be surmised) use the red grapes best suited to their terroirs.

Often considered the benchmark rosé in France, Provence has four appellations that each yield distinct wines; Coteaux d’Aix en Provence allows Cabernet Sauvignon to be added to the blend and this results in arguably the most structured rosé from the appellation.

In Bordeaux, Cabernet’s ancestral and spiritual ground zero, the rosé tradition is less pronounced; the AOP for pink production is slightly under nine thousand acres, about half the area for white and a fifth that of red. In Bordeaux, however delicious, rosé is definitely an afterthought. Unsurprisingly, the pink wine is also made from Merlot and Cabernet Franc.

Loire makes its own claim on the style, and is certainly the preference of many. Rosé de Loire and Val de Loire cover Anjou and Touraine, where—taking advantage of the cool climate—the quality is uncompromised; lightly textured, immediately drinkable with raspberry and red currant flavors. Anjou rosés, grown near the Atlantic, are made from Grolleau, Gamay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Malbec and Pineau d’Aunis.

From the icy limits of the north to the sweltering extremes of the south, styles of rosé are determined by many factors but there is certainly a strong case to made for them all.

Making A Rosé With The Capacity To Age, To Evolve, To Stand Up To Food

Even rosé’s most ardent fans may think of it as fun and festive springtime beverage; a crisp quaff meant to be consumed chilled within a year or two of vintage, and for the most part, they are not wrong.

There is a second style, however—one deserving not only of notice, but of understanding: The age-worthy rosé.

All wines have a unique dynamic created by a combination of terroir and target. In other words, a winemaker is bound by soil but not by motive; a number of factors go into the rather complex process of creating a rosé, beginning in the field and carrying through to the cellar. In order to create a wine that has the capacity to mature and improve, decisions are often made before the first vine is planted. Some grapes seem to have a natural affinity for aging—acidity and tannin levels are a large part of it, and so is a susceptibility to noble rot, since a concentration of sugars acts as a natural preservative. In making rosé, neither palate-parching tannin nor botrytis are particularly desirable, but acidity—in balance with natural fruit-forward dryness—is key.

So is having a full, unadulterated, un-doctored body: According to Nicole Rolet of Chêne Bleu in Vaucluse, “Some love-’em-and-leave-’em rosés are made with additives like tartaric acid to achieve the pale color and crisp flavors. That’s the stuff that’s generally going to condemn your wine to a short shelf life. It separates out over time, and the wine will fall apart and lose its aging potential.”

The inconvenient truth, however, is there are no surefire indicators of which rosés are meant to improve with age and which are meant for tonight; color can fool you and so can price; both are indicators that the product may be suited for the long-haul, but is not reliable enough to be fail safe. Color of the bottle may actually be a better gauge than color of the varietal since a producer will not package a seriously-structured rosé in a clear bottle.

The best strategy is to trust your purveyor, so naturally, you can safely assume that the wines offered below are the product of winemakers who took time and care to craft their wares, whenever you choose to drink them.

The 2021 Vintage: A Moment To Celebrate Classical Freshness And Moderate Alcohol Levels?

Something that can be said for certain about Vintage 2021 in France: Every region except Provence registered an output decline. Yields were 13% lower than the average of the last six vintages and 20% lower than the 2020 harvest, while the hardest hit AOPs (Loire Valley, Burgundy, Savoie and the Jura) were down 34% over 2020. This is the result of the worst French frost-related agricultural disaster since systematic record-keeping began in 1947, with 98% of the country affected and the wine industry given a particularly brutal wallop. Neither did the summer do its part; it was wet and cool in the north, dry and hot in the south.

And now the silver lining: Low yields may be a financial hardship on wineries, but they can be a quality godsend for consumers. Cool weather often leads to enhanced acidity (freshness) and lower sugar content, translating to lower alcohol-by-volume.

THE SOUTHERN RHÔNE

So dark in color are some of the Southern Rhône’s most celebrated rosés that they nearly defy the ‘blush’ concept. Of the vivid ruby tones found in Tavel, for example, Thomas Giubbi (co-president of the Syndicat Viticole de l’Appellation Tavel winemakers association) said, “We think of our wines as light red wines.”

But that isn’t fair to the category. In its very soul, rosé qualifies as neither red wine nor white wine. It may be (although rarely is; the practice is frowned upon) a blend of the two, but in nearly all cases, it is produced by crushing red-skinned, white-fleshed grapes and allowing a period of maceration lasting from a few hours to a couple days in which the juice is ‘dyed’ to a specific level; alternately, there is méthode saignée, which is essentially fermented free-run juice from red wine pressings.

Gigondas

Like nearby Châteauneuf-Du-Pape, Gigondas depends heavily on Grenache. Based on appellation laws, both the reds and the rosés must be made from up to 80% Grenache, with at least 15% comprised of Syrah and Mourvèdre. The grapes are grown at a higher elevation than Châteauneuf’s, often in terraced vineyards threaded with limestone under the looming Dentelles de Montmirail, with rocky, sandy, free-draining soils on the flatter, lower-lying land to the north and west. Although rosé only accounts for a scant 1% of the production in the entire appellation, it tends to be noteworthy stuff—serious and gastronomic a wine that recalls the rosés of yore that drank well into the years that followed.

1 Domaine Saint Damien, 2021 Gigondas Rosé ($33)

1 Domaine Saint Damien, 2021 Gigondas Rosé ($33)

Spreading over 112 acres, of which around 40 are in Gigondas, Domaine Saint Damien is the brainchild of Joël Saurel and his son Romain, who have lifted the estate—named for the patron saint of doctors—from humble roots to becoming one of the most reputable domains in Southern Rhône. This especially true in his superlative Gigondas, where fruit is drawn from the lieux-dits of Le Gravas, Pigières, La Louisiane, Les Souteyrades, La Moutte and La Tour.

80% Cinsault (planted in 1970) and 20% Syrah (planted in 2000) in the organically-farmed lieu-dit of La Moutte, this small production wine undergoes cold maceration for six hours followed by slow pneumatic pressing and fermentation in stainless steel tanks with occasional lees stirring. Delicately tinted, it shows rose petal, honeydew, lychee, pineapple and garrigue with a hint of pepper and crushed rock on the finish.

Côtes-du-Rhône

Côtes-du-Rhône is one of the largest single appellation regions in the world, covering millions of acres and producing millions of bottles of wine of varying degrees of quality. In Southern Rhône, it encompasses the majority of vineyards and includes hallowed names like Gigondas, Vacqueyras and Châteauneuf-du-Pape. The latter wines prefer to use their individual, highly specific ‘Cru’ names, but the truth is, many generic Côtes du Rhônes may come from plots just outside official ‘Villages’ boundaries—some only across the road or a few vine rows away from top vineyards—and among them, you can find wines with nearly the same level of richness at a fraction of the cost.

2 Domaine Les Grands Bois, 2021 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($16)

2 Domaine Les Grands Bois, 2021 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($16)

If more sommeliers became vignerons, the world might see more low-yield, unfiltered gems like those of Marc Besnardeau, who worked as a wine steward in Paris before following his dream into the vineyard. With wife Mireille Farjon, he took over Domaine Les Grands Bois, whose vines were planted in 1929 by Mireille’s grandfather. The estate is well-situated between St. Cecile and Cairanne, and after selling initially to négociants, the couple began bottling at the estate in 1997. They replanted some fields with Syrah and Mourvèdre, bought new vineyards, and expanded their holdings to its current size, 116 acres spread across seven communes: Sainte Cécile les Vignes, Lagarde-Paréol, Suze la Rousse, Tulette, Cairanne, Rasteau and Travaillan.

60% Grenache, 30% Syrah and 10% Carignan grown on chalky clay and harvested from vines ranging in age from 15-60 years. The wine shows black raspberries, cassis and clementine in a spicy package that highlights anise and honey up front, and with aeration shows deeper savory notes of fresh earth, mushrooms, wildflowers and crushed stone.

3 Domaine La Manarine, 2021 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($22)

3 Domaine La Manarine, 2021 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($22)

Created in 2001, Gilles Gasq established both the winery of Domaine La Manarine and the vineyards on a plateau northeast of Orange within the commune of Travaillan. He has expanded his holdings ever since, and now works with over eighty acres situated largely on ‘Le Plan de Dieu’—a terroir universally heralded for its deep, layered soils consisting of more than 60% hard limestone ‘galets’ which giving a unique minerality to the wines. Gasq says, “Our climate is typically Mediterranean: Relatively hot and dry with rains coming in the form of thunderstorms in late August; this helps provide the vines with the water necessary to finish the maturation process. Grenache is our main grape variety as it performs particularly well on this type of soil and gives wines more elegance and aroma than is otherwise common.”

60% Grenache, 40% young-vine Mourvèdre and 10% Syrah produced solely via direct-press and aged in stainless steel and concrete vats on fine lees prior to being bottled in the early spring following harvest. It is a friendly wine, full of spring berries and pink flowers with a fresh acidity that makes it a refreshing quaff as well as a potentially age-worthy bottle.

Ventoux

Ventoux is a large wine region in the far southeast of the southern Rhône, 25 miles northeast of Avignon and bordering Provence. Covering 51 communes, the vines are planted on the western slopes of Mt. Ventoux, a sort of ‘stray’ Alp removed from the range and towering over the landscape for miles around. Ventoux terroir and varieties are typical for Rhône, although noteworthy are the region’s Muscat produced for table grapes, which has its own AOP—Muscat du Ventoux.

4 Château Valcombe ‘Epicure’, 2021 Ventoux Rosé ($22)

4 Château Valcombe ‘Epicure’, 2021 Ventoux Rosé ($22)

Originally owned by Paul Jeune of Domaine Monpertuis, he opted to sell to Luc and Cendrine Guénard who worked under Jeune’s tutelage during the transition period. They now are proudly independent vignerons with a compulsion to further improve this jewel; their first efforts can be seen and tasted in the 2009 vintage. Certified organic in 2013, the 70 acres of Valcombe are situated in the shadow of the mountain, reaching one thousand feet. Four red grape varieties (Syrah, Carignan, Grenache and Cinsault) balance four white grape varieties (Clairette, Grenache Blanc, Roussanne and Bourboulenc); many vines over sixty years old, although parcels of Carignan and Grenache were planted in 1936. Soils are essentially limestone covered with the area’s famous galets, although deep in the subsoil, an unusual blue-inflected clay helps define the unique characteristics of Valcombe wines.

Vinified via the direct press method from a blend of 60% Grenache, 20% Cinsault, 10% Carignan and a touch of Clairette; all vines are of an average age of 40 years. It has a rich, focused plush texture with strawberry and peach in the foreground and an earthy and intriguing dose of eucalyptus behind.

Luberon

The list of grape varieties permitted in the relatively youthful Luberon appellation (created in 1988) is long, but Syrah and Grenache dominate plantings and must both be present in reds from here. Mourvèdre is also considered a primary red grape. Rosé represents about half the region’s output, and are generally made from the permitted red grapes, although they may legally incorporate up to 20% of white varieties, primarily Grenache Blanc, Clairette, Bourboulenc, Ugni Blanc and Vermentino.

5 Domaine de La Bastide du Claux ‘Poudrière’, 2021 Luberon Rosé ($25)

5 Domaine de La Bastide du Claux ‘Poudrière’, 2021 Luberon Rosé ($25)

Domaine de La Bastide du Claux was born in 2002 when Sylvain Morey—whose family’s roots in Chassagne-Montrachet goes back 400 years—uprooted. In the hills of Luberon, he chose to transplant some of his Burgundian know-how to Provence’s up and coming appellation. In the heart of the Luberon Natural Park, Morey cultivates a fragmented vineyard spread over 42 acres. Finding Luberon’s rich combination of soils, climates and exposures suited to a number of different grapes, he planted 14 varieties, each location chosen with circumspection. “When I arrived, there were not many growers bottling their own wines,” he says. “The vast majority of the production in Luberon was made by local cooperatives, and many of them valued quantity over quality and began to replant vineyards so that they could produce the maximum amount of grapes possible and save money with machine harvesting. These trends made it possible for me to affordably purchase interesting, low-yielding old-vine parcels that were no longer valued.”

50% Grenache from 55-year-old vines, 30% Cinsault, and 20% and Syrah, from south facing vines around the villages of Peruis and Ansouis. The grapes were pressed directly, the majority without maceration, with a portion of Grenache and Cinsault spending six or so hours on their skins after the pressing. Everything is done in cement and the wine ferments naturally, resulting in a great mineral character that shows its soil influence clearly and offers subtle red fruits and vigorous acidity along with a salty tang that typifies Mediterranean rosé.

PROVENCE

Tucked into the southeastern corner of France, Provence covers 125 miles of coastland—no vineyard in the appellation is more than 25 miles from the Mediterranean. And as suits the French Riviera, 3000+ hours of sunshine annually (paired with strong Mistral winds to keep things dry), allow vines to thrive in a hot, maritime climate without risk of fungal disease. Even so, as conditions become even hotter, a new way of thinking has begun to animate this deeply traditional region: Older varietals like Carignan, Barbaroux and Calitor being replaced by more commercially viable grapes like Grenache, Syrah and even Cabernet Sauvignon, although native standbys Mourvèdre, Tibouren and Vermentino continue to hold their ground.

There are pockets of well-received red and white wines throughout Provence, but the name of the game is pink; 82% of the Provençal output is rosé, nearly all crisply acidic and bone dry and in color, ranging from pale coral when made predominantly from Grenache to more deeply tinted Syrah-based wines. In fact, each shade has an official name based on a color chart developed by the Centre de Recherche and d’Expérimentation sur le Vin Rosé: Peach, Melon, Mango, Pomelo, Mandarin and Redcurrant.

Bandol

Conventional wisdom has taught us that wine grapes fare best in places where nothing else will grow; rocky, water-starved soil on precipitous hillsides make vine roots work harder, ramifying and branching off in a search of nutrients and, in consequence, producing small grapes loaded with character. Cue Bandol, the sea-and-sun-kissed region along the French Riviera, which is not only good country for grapes, it’s good country for the soul. Made up of eight wine-loving communes surrounding a cozy fishing village, Bandol breaks the Provençal mold by producing red wines that not only outstrip the region’s legendary rosé, but make up the majority of the appellation’s output. In part that’s due to the ability of Bandol vignerons to push Mourvèdre—generally treated as a blending grape in the Côtes-du-Rhône and Châteauneuf-du-Pape —to superlative new heights.

6 Château Pradeaux, 2021 Bandol Rosé ($41)

6 Château Pradeaux, 2021 Bandol Rosé ($41)

Situated on the outskirts of the town of Saint Cyr-sur-Mer, directly on the Mediterranean between Toulon and Marseilles, Château Pradeaux has been in the hands of the Portalis family since the French Revolution. In fact, Jean-Marie-Etienne Portalis helped draft the Napoleonic Code and assisted at the negotiation of the Concordat under Napoleon the First. Today, the domain is run by Cyrille Portalis, who continues to maintain the quality traditions of his forbears, assisted by his wife Magali, and their sons Etienne and Edouard. Although vineyards are planted almost exclusively to old-vine Mourvèdre, Château Pradeaux Bandol Rosé is composed of Cinsault as well.

Although the skin contact during a slow, gentle press only lasts about 24 hours, that is plenty of time for the perfectly ripe Mourvèdre to work its magic, and the addition of Cinsault (about half the cépage) creates an ideal structure that will allow this wine to evolve with grace. Layers of wild strawberry, blood orange and an herbal undertow of garrigue unfold beautifully.

Cassis

The entire vineyard area of Cassis is under five hundred acres, but most of the properties overlook the sea, which moderates the heat and creates an ideal climate for vine growing; the commune is known primarily for its herb-scented white wines, principally from Clairette and Marsanne (about 30% of Cassis production is rosé) and despite its name, it does not produce Crème de Cassis.

7 Domaine du Bagnol, 2021 Cassis Rosé ($41)

7 Domaine du Bagnol, 2021 Cassis Rosé ($41)

Sitting just beneath the imposing limestone outcropping of Cap Canaille, 700 feet from the shores of the Mediterranean, Domaine du Bagnol is the beneficiary of the cooling winds from the north and northwest and as well as the gentle sea breezes that waft ashore. Cassis native Jean-Louis Genovesi and his son Sébastien run the 18-acre estate.

Grenache, Cinsault and a touch of Mourvèdre combine to produce a wine that is perfumed with red-currant and strawberry aromas and provides a crisp and refreshing wash of citrus and crushed stone/slate minerality on the palate.

Côtes-de-Provence

The massive Côtes-de-Provence sprawls over 50,000 acres and incorporates a patchwork of terroirs, each with its own geological and climatic personality. The northwest portion is built from alternating sub-alpine hills and erosion-sculpted limestone ridges while to the east, and facing the sea, are the volcanic Maures and Tanneron mountains. The majority of Provençal vineyards are turned over to rosé production, which it has been making since 600 B.C. when the Ancient Greeks founded Marseille.

8 Domaine Gavoty ‘Grand Classique’, 2021 Côtes-de-Provence Rosé ($30)

8 Domaine Gavoty ‘Grand Classique’, 2021 Côtes-de-Provence Rosé ($30)

Roselyn Gavoty (the eighth generation of Gavoty to helm her family’s Roman-era farm; her ancestor Philémon acquired it in 1806) is on the cutting edge of viticulture. Situated along the Issole River in the northwestern corner of the Côtes-de-Provence, surrounded by oak and pine forests, the Gavoty family has worked the land without synthetic chemicals for decades, obtaining organic certification in recent years. The vineyard covers 150 acres in the commune of Cabasse (‘harvest field’ in the old Provençal language). Roselyn says, “Our vines are planted on clay-limestone soil, and produce a majority of rosé by the saignée method, involving bleeding off a portion of red must to create structure and depth.”

‘Grand Classic’ contains Grenache and Cinsault in roughly equal proportions, with Carignan playing a minor role. Rather than being pressed immediately after harvest, the wine macerates for several hours, and the saignée and first-press juice are vinified separately and blended until the wine displays its uncanny equilibrium—racy acidity wed to gleaming fruits and just the right amount of earthiness.

Bouches-du-Rhône

‘IGP’ (Indication Géographique Protégée) is a Europe-wide category that focuses on geographical origin rather than style and tradition, giving winemakers greater stylistic freedom than ‘AOP’ (Appellation d’Origine Protégée). As such, the boundaries of Bouches-du-Rhône are geographical, with the Durance river delimiting the north and the Rhône river making up the western border. The soils of the region tend to be poor, free draining and made up of anything from limestone-clay to gravel and sandstone; the lack of water forces vines to produce more concentrated grapes, leading to more concentrated and flavorful wine.

9 Mas de Valériole ‘Grand Mar’, 2021 IGP Bouches-du-Rhône – Terre de Camargue Rosé ($25)

9 Mas de Valériole ‘Grand Mar’, 2021 IGP Bouches-du-Rhône – Terre de Camargue Rosé ($25)

Mas de Valériole’s eighty-acre vineyards reflect diversity in multiple soil types: sand, clay, limestone, and alluvial loam deposited by the Grand Rhône. The reliably steady mistral wind blowing in from the Mediterranean mitigates the heat and facilitates the domain’s chemical-free approach to farming while ensuring modest alcohol levels in the wines. The property was acquired by the Michel family in the late 1950s and is now run by Jean-Paul and Patrick Michel. Produced from a variety of cépages, including Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, plus crossings like Caladoc (Grenache and Malbec) and Marselan (Grenache and Cabernet Sauvignon) which are particularly well-suited to the Camargue’s climate, Mas de Valériole’s wines combine the breezy freshness of Provence with a sense of wildness and an underlying salinity that is representative of Bouches-du-Rhône.

‘Grand Mar’ Rosé is 100% Caladoc, fermented with indigenous yeasts (unusual for rosé production) in stainless steel tanks to preserve freshness. The wine is enticing with vibrant notes of ruby-red grapefruit and white peach behind crackling acidity—a wine that never met a salmon dish it did not love.

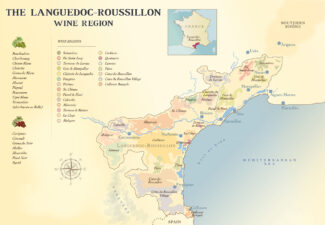

LANGUEDOC-ROUSSILLON

Sun-baked and sensual, threaded with rivers and capped by the mountains of Corbières, Languedoc-Roussillon relies on over a hundred grape varieties to produce more than a third of all French wine. Historically, this wine was copious, inexpensive and rather forgettable—everyday wine for the tables of ordinary people. Since the mid-twentieth century, however, with the advent of irrigation in the foothills and coastal plains of Southern France coupled with improved techniques, the region now boasts fewer vines that produce wines of increasing quality. A jigsaw of soils and a broad swath of microclimates creates ideal terroir for the warm-weather, full-bodied varietals often associated with the Rhône, while sharp diurnal shifts allow for the preservation of aroma and natural acidity, resulting in wines of extraordinary balance. A further plus is that Languedoc-Roussillon’s hot, dry climate discourages the growth of mildew and fungi, making synthetic pesticides and herbicides less necessary. As such, it has become a proving ground for organic and biodynamic producers.

10 Mas Jullien, 2021 Languedoc Rosé ($35)

10 Mas Jullien, 2021 Languedoc Rosé ($35)

Among the early pioneers of the modern ‘Larzac style’ is Olivier Jullien: His forty terraced acres, with two distinct soil types—calcaire and argilles—was established in 1985, and his domain, Mas Jullien, is a paradigm of the region. Having witnessed first-hand Languedoc’s tradition of over-cropping to produce bulk wine, he recognized that the economic plight of local independent farmers may have failed to take advantage of the appellation’s promise. With a degree in enology to shore up his conviction that the area had the potential to produce world-class wine, he showed his iconoclastic hand early by pulling out vineyards and re-planting trees in an effort to restore balance to the local ecosystem. His wines are delightful examples of this balance, imbued with the distinct characteristics permitted by elevation and proximity to the sea.

A saignée rosé made from juice that is bled off the skins of red grapes from Jullien’s vineyards on the Terrasses-du-Larzac. A blend of Cinsault, Carignan and Mourvèdre, though the blend can change from vintage to vintage. Fermentation takes place in stainless steel with native yeast, aging in Stockinger foudres of mixed ages. It is a structured and somewhat wild wine of deep, earthy complexity showing garrigue and wet stone behind strawberry and watermelon.

BORDEAUX

Today, rosé is a serious wine in Bordeaux, but still, ‘serious’ must be viewed on a sliding scale compared to the reds. Even this is an improvement; in days not too long ago, it was not only uneconomical to turn red wine grapes into pink, it was generally only made in weaker vintages, when juice might be bled off reds to make a ‘weak red’ or darker pink or from fruit from vines too young to make viable reds. In 2010, the Bordeaux Wine Board reviewed its marketing strategy and the role of Bordeaux in the international market and started to actively encourage Bordeaux rosé as a means of attracting younger drinkers to old-guard wines. In part, the campaign has succeeded, and sales of rosé (as opposed to ‘clairet’, the darker red version that is often the product of saignée rather than direct-press) have grown. Fresh Bordeaux rosés remain a unique beast in that they have a blue tinge, with no hints of orange-salmon in their youth, although with age, they fade toward this hue.

11 Château La Rame, 2021 Bordeaux Rosé ($24)

11 Château La Rame, 2021 Bordeaux Rosé ($24)

La Rame’s fifty acres overlook the Garonne; they face south and the vineyards are planted in clay-limestone with an exceptional substratum marked by fossilized oyster shells dating from the Tertiary era. Further down the slope, where sandier soils predominate, the estate’s Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot thrive. The property was purchased by the father of the current owner, Yves Armand, at a time when the appellation had fallen out of favor. The family has undertaken to re-establish their Sainte-Croix-du-Mont AOP as an appellation to rival the great estates nearby.

A relatively new addition to the Rame portfolio, the grapes (80% Cabernet Sauvignon and 20% Merlot) are sourced from a five-acre parcel of younger vines on the flanks of a hill that descends towards the Garonne. The wine is produced via the direct-press method and is fermented in temperature-controlled vats for six months before it is bottled. It shows fine aromatic persistence with notes of red currant, raspberry and pear with a hint of banana. About 15,000 bottles are produced annually and only a few thousand are exported to the USA.

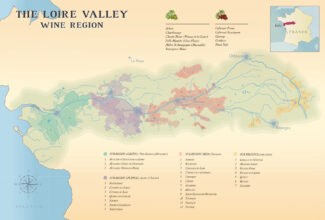

THE LOIRE VALLEY

Rosé de Loire adds yet another dimension to French blush. Extending across the Anjou and Touraine AOPs, it covers about 2000 acres and is responsible for more than a million gallons of rosé every year. Its color lends itself to dramatic descriptors ranging from ‘flamingo pink with a hint of poppy’ to ‘gleaming raspberry pink with a glimmer of violet.’ These wines are generally dry, but there is a subset that is off-dry and another subset, Crémant, that sparkles. There is even a ‘Primeur’ (or ‘Nouveau’) style, a much fruitier wine that is almost entirely free of tannins—a result of being fermented using the Beaujolais method of carbonic maceration. Like the red wines of Loire, the principle grapes used in the rosé are Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Grolleau (Noir and Gris), Pineau d’Aunis, Gamay and/or Pinot Noir. Beyond color, Rosé de Loire is delightful elegance in a glass; Rosé d’Anjou in particular is noted for its reflection of terroir.

Saumur

As a fair representation of the Middle Loire, Saumur—radiating outward from the town center into neighboring administrative departments of Vienne and Deux-Sèvres—is primarily Chenin country, with a strong tradition of producing sparkling wines, for which the geology is particularly well suited. The town sits on a mound of tuffeau—the porous, sandy-yellow rock which underpins several of the central Loire’s top vineyard areas. Many miles of underground cellars have been cut directly into this soft rock, providing a cool, temperature-moderated environment perfect for storing méthode traditionelle wines during their lees aging. The reds, making up around 20% of the output, are built around Cabernet Franc, although Cabernet Sauvignon and Pineau d’Aunis can figure into the blend in minor quantities. Rosé gets afterthought focus and is only around 5% of total output; the appellation for rosé wines ‘Cabernet de Saumur’ has the same borders as Saumur AOP and is reserved for off-dry wines with at least 10 grams per liter residual sugar.

12 Château de Chaintres ‘Les Hirondelles’, 2021 Saumur Rosé ($32)

12 Château de Chaintres ‘Les Hirondelles’, 2021 Saumur Rosé ($32)

The de Tigny family has not only owned this property since 1938, a good number of the vines planted back then are still in production. In 2017, the estate hired Jean-Philippe Louis as cellar master, and he immediately began to transform the vinification philosophy with a precise, intuitive and non-interventionist hand. The property’s tuffeau makes for Chenin of vigorous acidity and penetrating precision as well as transparent Cabernet Franc, which thrives in the heat-retaining sand that covers the limestone, possessing a complexity and longevity that extends far beyond its fresh, finesse-driven profile.

100% Cabernet Franc, pressed directly, fermented spontaneously, and aged in steel with a bare minimum of sulfur. Floral up front with rose petal and geranium notes that meld into strawberry and mandarin flecked with flint over a chalky framework.

Anjou

Anjou sprawls across 128 communes, mostly south of the towns of Angers in the west and Saumur in the east. Monasteries played the largest role in developing Anjou’s wine trade, as each enclave had its own walled vineyard. But it was French royalty who secured the region’s reputation, beginning nearly a thousand years ago when Henry Plantagenet became King Henry II of England. Anjou’s terroir is a matter of black and white: it’s divided into two subsoils as different as day and night. First, Anjou Noir, composed of blackish, dark, schist-based soil along the south-eastern edge of the Massif Armoricain, then, Anjou Blanc, lighter-colored soils made up of the altered chalk at the south-western extremity of the Paris Basin.

13 Château Soucherie ‘L’Astrée’, 2021 Rosé-de-Loire ($30)

13 Château Soucherie ‘L’Astrée’, 2021 Rosé-de-Loire ($30)

Perched on a rise overlooking the Layon river, Soucherie is considered one of the most beautiful domains in Anjou. Roger-François and Pascal Beguinot have transformed 90 acres of limestone, clay and schist into multiple lieux-dits spread across Anjou, Chaume, Coteaux-du-Layon and Savennières. Around the winery, 54 acres are planted on a southern hillside sheltered from the winds; the 11 acres in Chaume contain vines over 70 years old while the four acres in Savennières (Clos des Perrières), loaded with shale, produce wines noted for their minerality. Maître de chai Thibaud Boudignon is leading the charge towards 100% organic viticulture through the principles of ‘agriculture integrée’—a ‘whole farm’ management system intended t deliver more sustainable agriculture by combining modern technologies with traditional practices according to a given site and situation.

The wine is dry and mineral-driven, produced from 70% Grolleau and 30% Gamay planted to clay, sandstone and schist soils. A ‘direct press’ rosé with élevage in cuve and bottling in April of the spring following harvest. The nose of white peach is underscored by herbal notes of dandelion greens and pineapple sage are complimented by a palate juicy with strawberry and watermelon notes.

- - -

Posted on 2024.03.22 in Anjou, cassis, Bandol, Luberon, Ventoux, Terrasses du Larzac, Gigondas, Côte-de-Provence, Rosé de Loire, France, Bordeaux, Wine-Aid Packages, Languedoc-Roussillon, Loire, Provence, Southern Rhone | Read more...

Gigondas Steps Out of Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s Shadows: A Dozen Southern Rhône Producers Make The Case Gigondas 2021 & 2020 Ten-Bottle Pack For $399 + A Rhône With Substance, But No Pretense 12-Bottle ‘Cairanne’ Pack For $159 (Limited)

The long shadow cast by Châteauneuf-du-Pape over Southern Rhône is bit like Mount Doom’s shadow over Mordor, only with a bit more garrigue and spice. So synonymous has the powerhouse cru been with style and standing in the region that nearby appellations cannot escape comparisons—generally to the unfavorable side—and until recently, could not really compete.

As such, it is high time somebody challenged the CdP supremacy, and Gigondas seems the appellation best poised to make a clean break from its glossier embossed cousin.

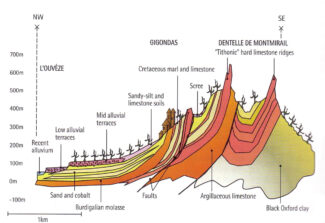

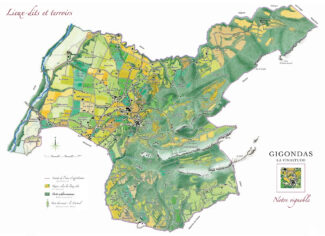

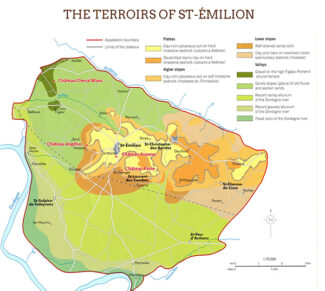

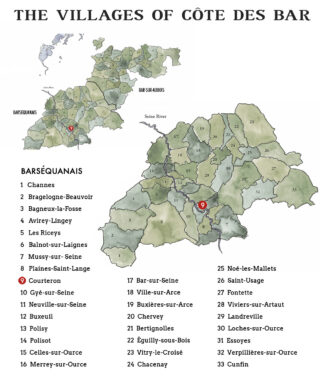

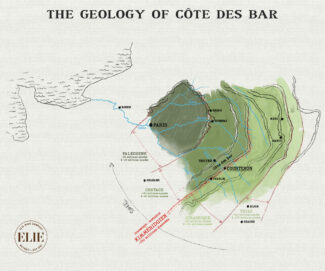

It’s a struggle that began in 1971, when Gigondas became the first of the Côtes du Rhône Villages appellations to be elevated to Cru status. Gigondas vineyards are found along the base and slopes of the first Dentelles de Montmirail foothills, where the combination of limestone soils on the Montmirail slopes to the east, and rocky, sandy, free-draining soils on the flatter, lower-lying land to the north and west create an ideal terroir across a multitude of microclimates, each with its own distinct claim to fame.

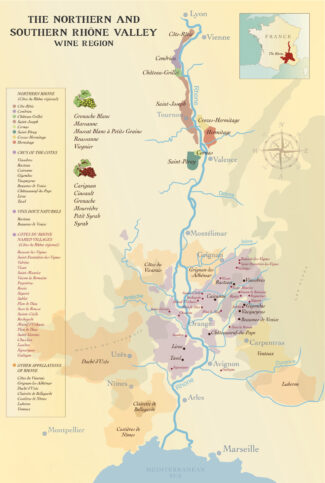

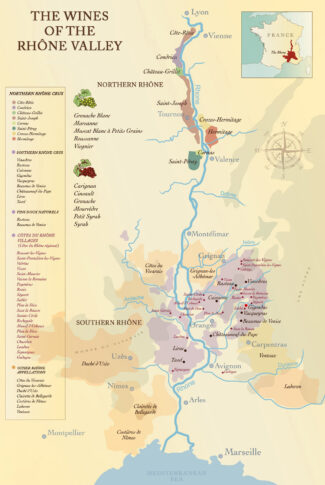

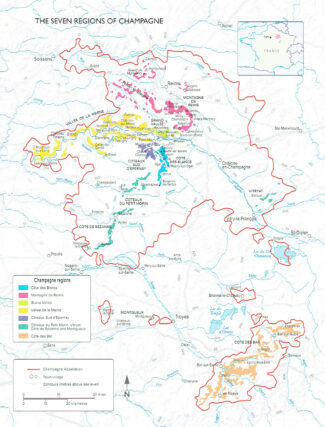

Southern Rhône River Crus

The Rhône is generally divided into north and south; but they are by no means equal in either style or output. Whereas the north contains some heavy-hitting Crus (Côte-Rôtie and Hermitage, to name a couple), it only represents 5% of the Rhône’s total production. In Northern Rhône, the sole red wine grape allowed is Syrah.

The south, fanning out from both banks of the Rhône River, is not as Syrah-focused, relying on a cornucopia of other varieties—Grenache, Carignan, Mourvèdre and Cinsault for reds and for whites, Marsanne, Roussanne, Bourboulenc, Clairette and Viognier, although many reds from the region—depending on AOP regulations—make use of white grapes in red wine blends to add floral highlights and soften harsh tannins.

The south is further divided into nine individual Crus—Beaumes des Venise, Cairanne (elevated in 2016), Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Gigondas, Tavel, Cairanne, Rasteau (changed in 2009), Vacqueyras and Vinsobres. Each has its own legion of fans, and each expresses the multiple terroirs of the south with individual interpretations: Tavel, of course, is known for its dry rosé, Vinsobres for it’s vividly acidic reds, Cairanne for its fleshy, Grenache-dominant quaffers, Lirac for its juicy, complex reds and fresh, floral whites. Southern Rhône’s most famous appellation, however, is Châteauneuf-du-Pape, and for good reason: These wines are impressively structured, deep in black fruits and spice with hints of roasting meats and occasionally a dash of funk; top examples run an equally impressive price tag.

Which brings us to Gigondas. Once referred to as ‘the poor man’s Châteauneuf-du-Pape’, quality improvements have been so striking over the past decade or so that it is high time we started thinking of it Châteauneuf-du-Pape affordable equal, perhaps ‘the smart man—and woman’s—Châteauneuf-du-Pape.’

Gigondas vineyards at the Dentelles de Montmirail foothills.

Geological map of the Dentelles de Montmirail formations. The town of Gigondas is in the middle. (Courtesy of Gargantuan Wine)

Gigondas, A Red That Takes You Into The Woods And To The Shore

Bastien Tardieu is the lead oenologist at family-operated négociant Tardieu-Laurent, which works with more than 100 growers throughout the Rhône Valley.

He’s also one of Gigondas’ most vocal flag-wavers: “Quality has improved immeasurably the last ten years,” he says. “Advances can be attributed to Cru appellations like Gigondas being held to the same restrictive regulations as Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Topography also plays a role: Gigondas, along with neighboring Vacqueyras and Beaumes de Venise, sits along the slopes of the Dentelles de Montmirail, the ragged limestone formation that towers above the Southern Rhône. The outcrops of the Dentelles protect against the morning sun and extend the growing season. Its altitude allows for a wide day-night temperature range that maintains acidity and balance in the grapes.”

The ideal Gigondas displays a bouquet evoking fresh forest berries, classic potpourri and botanical herbs that are complemented by exotic spice notes that build in the glass. The wine should stain the palate with intense raspberry, cherry cola and lavender pastille, flavors that steadily deepen with aeration.

Like most of Southern Rhône, Grenache is the appellation’s backbone, augmented by Mourvèdre and Syrah and—minus Carignan—a handful of other traditional Rhône varieties are ‘blend-approved.’

But the unique flavors of Gigondas extend beyond the familiar garrigue, which takes herbal hints from the nearby woodlands and native scrub bushes—wild thyme, sage, rosemary and lavender. According to Louis Barruol, owner of Château de Saint Cosme, a Gigondas estate that dates to the 15th century, “There is an unmistakable freshness about Gigondas wines—a quality that does not arise from altitude or acidity alone. It is a saltiness and minerality reminiscent of the sea.”

Gigondas 2021 & 2020: Ten-Bottle Package For $399

The producers featured in this week’s package (10 bottles 2021 and 2020 Gigndas, numbered below) are sensitive to the traditions of their appellation and the nuances of their terroir, and are convinced that a return to the herbal essence of Southern Rhône—something occasionally lost amid Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s pursuit of power and ultra-ripe fruitiness—should be their signature distinction.

Domaine de Font-Sane

As in much of modern Gigondas, especially among forward-looking producers, sustainable agriculture has become less an option and more a mandate. Such is the case at Domaine de Font-Sane, where Véronique Cunty-Peysson and her husband Bernard run the160-year-old estate.

“Fertilization is done every year by adding organic compost,” says Véronique. “These natural products help maintain the humus levels and promote good exchanges between the soil and the plant, and quality is always preferred over quantity.”

Having recently completed his Master’s degree in International Wine Business, their son Romain has joined the team and speaks to the unique quality of the 40 acre estate: “We have the advantage of a rich variety of soils boasting five unique terroirs—clay-limestone, pebbly, sandy, alluvium, sandy loam. The blending of these makes for a complete wine enriched by the multiple characteristics that each soil type gives.”

In 2020, Font-Sane obtained a new certification called HVE (High Environmental Value); this a program awarded to wineries who take a ‘lutte raisonnée’, or reasoned approach, from wine cultivation to bottling, by promoting environmentally friendly practices.

1. Domaine de Font-Sane ‘Tradition’, 2021 Gigondas ($25)

1. Domaine de Font-Sane ‘Tradition’, 2021 Gigondas ($25)

An exhuberant and youthful wine, full of fiery red fruit, savory complexity and fine-grained tannins. Three-quarters Grenache blended with around 25% Syrah and small amounts Mourvèdre and Cinsault, it’s big wine at 15% abv., but one which is quite well integrated and does not seem to need a lot of cellar time—drink to enjoy tonight.

Domaine des Pasquiers

“Provence is naturally a land of vine,” says Philippe Lambert, who along with his brother Jean-Claude and their children, Matthieu and Perrine, run des Pasquiers, founded by their grandfather in 1935. The sprawling estate, over 200 acres, stretches across multiple appellations including IGP Vaucluse, Côtes du Rhône, Côtes du Rhône Villages ‘Plan de Dieu’, Côtes du Rhône Villages ‘Sablet’ and Gigondas.

“Our situation is at the foot of the Dentelles de Montmirail,” Jean-Claude explains, “where terraces of red clay are covered by pebble stones which reflects the sun’s heat at night and keep coolness during day. The slopes of Sablet are gentle and the sandy soil and gravel brings finesse and mineral qualities to the wine. Finally, Gigondas, where the soil, combination of the Secondary to the Quaternary Periods, produces structured and unique terroirs for very complex wines.”

2. Domaine de des Pasquiers, 2020 Gigondas ($30)

2. Domaine de des Pasquiers, 2020 Gigondas ($30)

50% Syrah and 50% Grenache, with a pure Provençal style replete with blackberries, sandalwood, garrigue and white pepper. Tannins are ripe and the acids striking, but both are beautifully integrated into the flesh of the wine and create a backbone that suits both early drinking and long-term cellaring.

Pierre Amadieu

Amadieu family roots have been digging into Gigondas soils for nearly a hundred years, but with each new generation comes a new focus.

For Pierre Amadieu Jr. it is paramount to improve wine quality every year: “We look for elegance, length on the palate and a ‘Burgundy’ freshness in our wines. A careful parcel selection allows us today to elaborate different cuvées of Gigondas which express each of our exceptional terroirs in its own way.”

The family affair includes three of his cousins: Henri-Claude, the eldest son of Claude and Muriel, who heads the sales department, his brother Jean-Marie—an agricultural engineer and oenologist, who works closely with Pierre in the winery, and their sister Marie who caters to their private customers. With production at over 50,000 cases annually, there is work enough to go around.

The Amadieu situation inspires a bit of eno-envy. It is located on north/northwest-facing hillsides in the north-east Gigondas where altitudes range from 750 and 1600 feet. With 338 acres surrounded by garrigue and holm oaks, Amadieu is the largest landowner in the appellation.

Strolling the vineyard, Claude Amadieu waxes philosophically on these beautiful acres: “Our exposure gives a perfect aeration to vines and avoids an excessive period of sunshine in full summer. It brings our wines freshness and allows long maturation without risking drought or bitterness. The expression of Grenache, Syrah, Mourvèdre, Cinsault (for rosé) and Clairette (for white wine) on these terroirs among the highest of the appellation, is very personalized—our wines are powerfully spiced.”

3. Pierre Amadieu ‘Romane Machotte’, 2021 Gigondas ($31)

3. Pierre Amadieu ‘Romane Machotte’, 2021 Gigondas ($31)

80% Grenache, 20% Syrah from 45-year-old vines grown on hillside terroirs of limestone and marl. An expressive wine with blackberry, boysenberry and smoked plum notes laced with violet and white pepper on the nose while the palate shows dusty earth, sweet tobacco and charred mesquite.

4. Domaine Grand Romane ‘Cuvée Prestige – Vieilles Vignes’, 2021 Gigondas ($36)

4. Domaine Grand Romane ‘Cuvée Prestige – Vieilles Vignes’, 2021 Gigondas ($36)

65% Grenache, 20% Mourvèdre, 15% Syrah. Domaine Grand Romane is a unique vineyard located on the highest part of Amadieu estate, 1600 feet above sea level, where the pebbly limestone terroir is poor and forces the vines to put down deep roots. Black fruits and cinnamon appear in the bouquet, and the silken mouthfeel is washed with generous creamy berries, pepper and vanilla with a long finish showing flavors of grilled meat.

Domaine Saint-Damien

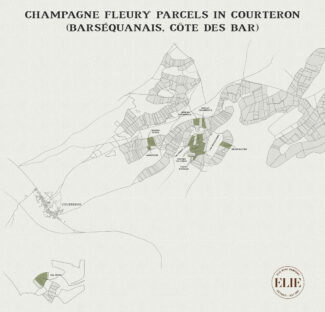

With well over a hundred acres spread between Gigondas, Plan de Dieu, Côtes-du-Rhône Villages appellations, IGP and Vin de France, the terroir at Saint-Damien is varied. But in Gigondas, the focus is on plot specific sites, including the lieux-dits Gravas, Pigieres, La Louisiane, Les Souteyrades and La Moutte.

Joël Saurel, along with his wife Amie and winemaking son Romain, runs the estate in its modern incarnation, but the Saurel family had been tending vineyards her since 1821, selling to négociants. Joël began producing wine in 1996, and in 2012, the vineyards were certified by Agriculture Biologique.

Gigondas remains the flagship of the estate; Romain says of the family’s Gigondas acres: “Most of the vines are quite old and cropped low. The wines are aged in large, traditional concrete vats and old foudres and usually bottled on the young side to preserve freshness.”

5. Domaine Saint-Damien ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2021 Gigondas ($41)

5. Domaine Saint-Damien ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2021 Gigondas ($41)

80% Grenache planted in 1964, 20% Mourvèdre planted in 1977 in several lieux-dits located on the lower terraces of the Dentelles de Montmirail. The grapes are hand-harvested and fermented on skins in large concrete vats for five weeks before ageing another year in old foudres. The wine shows a touch of cedary oak on the nose alongside the black cherries and subtle garrigue notes ending in a gentle wash of dusty tannins and a hint of licorice.

Domaine des Florets

Jerome Boudier has owned the 20-acre Domaine des Florets since 2007—and he followed a circuitous path to get there. After advising CAC companies for 25 years on environmental protection and sustainable development, he wanted to launch a second career in direct contact with nature and make wine by integrating sustainable development concepts into the art of vinification.

He is almost zen in his approach: “In winemaking, as in all pursuits in life, there are no ready-made solutions. We must constantly seek the right balance and identify the necessary compromises to build a sustainable and benevolent model. My mission goes far beyond making good wine, but it must also be well-made wine that honors sacred nature.”

In the field, he puts this philosophy into practice by choosing an environment favorable to species beyond grape vines, developing the rich biodiversity inherent in terroir. He has nice spot with which to work—the top of the Dentelles de Montmirail at an altitude of 1650 feet, on steep terrain protected by high limestone rocks.

The same deep thinking attends Boudier in the cellar: “Throughout the winery, I strive to limit inputs and limit consumption as much as possible. Beyond the water and biodiversity aspects, a low-carbon and eco-responsible approach is favored from planting to packaging. We have a duty to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions through our practices and the carbon storage capacity of our soils.”

6. Domaine des Florets ‘Synchronicité’, 2020 Gigondas ($53)

6. Domaine des Florets ‘Synchronicité’, 2020 Gigondas ($53)

From a mountaintop vineyard, the grapes (95% Grenache and 5% Syrah) undergo a gentle cold maceration, and a two-to-three-week long vatting punctuated by pigéage, following which the wine is aged for a year in oak. It shows crushed red fruit up front—strawberries, raspberries and pomegranate—and then with aeration, savory notes appear as subtle cocoa powder and pie spice.

Domaine Raspail-Ay

Aÿ is a name irrevocably linked to Champagne; remove the umlaut and the story becomes Gigondas. Domaine Raspail-Ay is run by single-minded producer Dominique Ay, whose portfolio is limited to a single bottling of Gigondas—no more than 6000 cases annually—and a handful of rosés, consistently rated among the most iconic wines of the region.

Ay’s are traditionally produced wines; classical blends given classical treatments in concrete vats and aged in large oak foudres. With the imposing rock formations of the Dentelles de Montmirail (the last outcrop of the mighty Alpine chain) looming as a backdrop, this estate represents the embodiment of the old adage, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

His plantings are 70% Grenache, 20% Syrah and 10% Mourvèdre, all on the plain in front of the quaint village of Gigondas; old vines and limited yields are responsible for naturally high level of ripeness and concentration.

Ay describes the process after harvest: “We destem entirely and ferment in cement vats, filling each with a mix of the three varieties as they ripen during the harvest, keeping track of what parcels and varieties wind up in each vat with a small chalkboard on the wall. There’s a modest single pump-over per day, some pigéage before the vats settle on their own. The assemblage is done soon after malo, and the wine is then racked off into a range of large foudres and some demi-muids as well as a portion that remains in cement.”

In the last several years, as the domain achieves near cult-like status, Dominque’s son Christophe and daughter Anne-Sophie have joined him in the endeavor.

7. Domaine Raspail-Ay, 2020 Gigondas ($51)

7. Domaine Raspail-Ay, 2020 Gigondas ($51)

The 2020 vintage produced many superlative wines, and this is one of them: 70% Grenache, 20% Syrah and 10% Mourvèdre, destemmed and aged in concrete vats, 600-liter oak casks and large, neutral foudres, it offers upfront notes black raspberry, kirsch, and garrigue mingled with exotic spices and subtle hints of violet.

Domaine de Cabasse

The three-star hotel at Domaine de Cabasse, housed within a traditional Provençal ‘mas,’ may garner more press, but the working winery’s 90 acres of vines (30 of which surround the hotel) produce world class Gigondas. The name Cabasse comes from the Italian ‘Casa Bassa,’ meaning ‘the house under the village’—a reference to the14th century when the pope used to live in Avignon.

In 1991, the Haeni family, originally from Switzerland, acquired the domain to focus on the vineyard, their true passion. It is currently run by the gregarious Benoît Baudry and his wife Anne.

Branching beyond Gigondas into Séguret and Sablet and Gigondas, the varietal selection covers the gamut of Southern Rhône standbys—Syrah, Grenache, Mourvèdre, Counoise, Carignan, Clairette along with a host white grape varieties, which Cabasse bottles as Côtes-du-Rhône Villages appellation. The plots are not overly large and are surrounded by hedges and trees that protect the vines from the cold mistral which can blow violently from the north. The soils are mainly composed of weathered limestone with varying clay, sand and stone.

8. Domaine de Cabasse ‘Jucunditas’, 2020 Gigondas ($51)

8. Domaine de Cabasse ‘Jucunditas’, 2020 Gigondas ($51)

A traditional blend of 80% Grenache, 10% Syrah, and 10% Mourvèdre; red cherry syrup and raspberry compote appear up front in both aroma and palate, with blackberry, plum, and pepper rounding out a long finish that whispers garrigue.

Domaine Les Pallières

Woven into the foothills of the brooding Dentelles de Montmirail, Les Pallières has been a force in Gigondas requiring reckoning since the fifteenth century. And up until the end of the last century, it was in the hands of the same family.

In 1998, Daniel and Frédéric Brunier of Vieux Télégraphe were convinced to take a shot at reviving Les Pallières from a couple decades of neglect, and the Pallières’ renaissance soon followed. The raw material was superb, with vineyards ranging from a few hundred feet to over one thousand in altitude, with varying proportions of sand and clay interwoven with limestone scree that has descended from the Dentelles. Among the improvements seen to immediately were reinforced terraces to allow for better water retention and a new winery building capable of receiving harvested parcels individually in gravity-fed tanks. The many lieux-dits, once blended into a single cuvée, have been separated into two in an effort to best express two remarkable personalities. Cuvée ‘Terrasse du Diable,’ encompasses the low-yielding vines from the higher altitudes while Cuvée ‘Les Racines’ highlights the vineyard parcels surrounding the winery—the origin of the domaine with the oldest vines—with the emphasis on freshness and extravagant cornucopian fruit.

9. Domaine Les Pallières ‘Les Racines’, 2021 Gigondas ($58)

9. Domaine Les Pallières ‘Les Racines’, 2021 Gigondas ($58)

Les Racines is a parcel-selection of the oldest vines in the lieu-dit Les Pallières. 80% Grenache, 15% Syrah and Cinsault (co-planted) and 5% Clairette; the palate is high-toned and elegant, lush with black cherries, garrigue, olives and crushed stones.

10. Domaine Les Pallières ‘Terrasse du Diable’, 2021 Gigondas ($53)

10. Domaine Les Pallières ‘Terrasse du Diable’, 2021 Gigondas ($53)

90% Grenache, 5% Mourvèdre, 5% Clairette from a 25-acre vineyard site of red sandy clay, limestone and scree—vines average 45-years-old. A very representative array of Provençal high-notes, plum, cherry and forest berries wreathed in black olive, licorice, mint, eucalyptus and rosemary.

Domaine Les Pallières ‘Terrasse du Diable’, 2018 Gigondas ($58)

Domaine Les Pallières ‘Terrasse du Diable’, 2018 Gigondas ($58)

90% Grenache, 5% Mourvèdre, 5% Clairette. A blend of rustic elegance, with elements of smokey plum near the surface and chalky tannins beneath the surface.

Domaine Santa Duc

At Santa Duc, in the verdant environs of Gigondas, heritage is as deep as the iron-rich soils. Six generations have leapfrogged each other as caretakers of the storybook estate at the foot of the Dentelles de Montmirail hills and each has brought to the party a unique respect for terroir and tradition. Yves Gras, Domaine Santa Duc’s winemaker for 32 years, became a standard bearer for innovation with his elegant wines; he replaced barrels with 3600-liter casks to tone down the oak and championed a greater percentage of Mourvèdre used in cuvées. His ongoing quest for cooler terroirs capable of producing great wines ultimately took him from the plateau of Gigondas to Châteauneuf-du-Pape (10 miles to the southwest), where he was able to purchase several choice parcels.

With the 2017 vintage, Yves’ son Benjamin Gras took over the domain and quickly proved himself to be as much a visionary as his father, switching immediately to biodynamic agriculture and building a state-of-the-art winemaking facility on the property. Benjamin has the passion, the Gras DNA, but also the educational pedigree to buoy his future: After obtaining a diploma in oenology at the University of Bourgogne in Dijon, he spent time at Domaine de la Romanée-Conti and Bodega Vega-Sicilia, and the OIV MSc in Wine Management program gave him the unprecedented opportunity to visit more than two dozen wine producing countries and study their techniques, their terroirs, and their traditions.

Domaine Santa Duc ‘Clos Derrière Vieille’, 2018 Gigondas ($57)

Domaine Santa Duc ‘Clos Derrière Vieille’, 2018 Gigondas ($57)

An iron butterfly, with both weight and lyrical lightness from the limestone-rich clos behind the village of Gigondas; 80% Grenache and 10% each Mourvèdre and Syrah, the wine is resinous with orange peel, pomegranate and raspberry. smoked garrigue, fresh thyme and lavender.

Domaine Santa Duc ‘Les Hautes Garrigues’, 2018 Gigondas ($73)

Domaine Santa Duc ‘Les Hautes Garrigues’, 2018 Gigondas ($73)

50% Grenache, 50% Mourvèdre—this is Santa Duc’s flagship, a biodynamic gem sourced from 75-year-old vines planted on the sandy soils of the Les Hautes Garrigues lieu dit. It offers a brilliant bouquet of ripe wild strawberries, dried plums, blueberries, ground pepper, garrigue and sweet leather with a long, mineral-driven finish.

The Pinnacle

Domaine des Bosquets

“Since Julien Brechet took control of his family’s 64-acre estate in 2006, Domaine des Bosquets has been moving steadily up the Gigondas hierarchy, and in 2016 they produced not only some of the best wines of the appellation but of the entire southern Rhône.”

That song of praise, well-deserved, is from Antonio Galloni’s widely read ‘Vinous’ and reflects the spirit of the Domaine des Bosquets estate. Prior to taking over, Julien Brechet apprenticed at Château de Vaudieu under Philippe Cambie, and at Bosquets, he begun to map out his terroirs through careful studies and micro-vinifications. Rather than rob his Villages-level Gigondas of its best parts, his parcel wines are only made in limited quantities. Among the lieux-dits Julien farms are Jasio, La Colline, Le Plateau, Les Bosquets, Roche, Les Routes, and Les Blânches, where the planting principal grape variety is Grenache (70%), with 20% Syrah, 8% Mourvèdre, and 2% Cinsault with tiny percentages of other permitted varieties, both red and white.

His estate is now certified organic, a process he started in 2015, and he’s begun implementing biodynamically practices. Cover crops are encouraged and are plowed under to provide nutrients to the soils and ensure the vines penetrate deep into the subsoil. The average age of his vines is 50 years, and the soils range from sand to various gravels and types of clay – some with high levels of chalk. Average yields are 23 hl/ha for vines destined for the village Gigondas, while it drops down to as low as 15 hl/ha for some of the parcel wines. Harvests are manual to ensure a strict selection of fruit, and fermentations are now entirely with indigenous yeasts.

With these farming changes, Julien has noticed better stem maturation at harvest and uses up to 30% whole clusters. His Gigondas wines are aged for two winters in French oak barrels ranging in size from 228 liter to 2300 liter. He prefers seasoned barrels to new and ages his parcel wines entirely in neutral French oak.

Domaine des Bosquets ‘Le Regard Loin’, 2020 Gigondas ($288)

Domaine des Bosquets ‘Le Regard Loin’, 2020 Gigondas ($288)

The culmination of Julien Brechet process of strict selection and micro-cuvée blending fruit from La Colline, Le Plateau, Les Routes, and Les Roches lieux-dits. 70% Grenache with 20% Syrah, 8% Mourvèdre and 2% Cinsault with tiny percentages of other permitted varieties, both red and white, the wine spends 12 months in second-fill oak barrels before blending, then another 12 months in sandstone amphorae before bottling. A nice mix of black raspberries, blueberries, licorice, and herbes de Provence.

RECENT ARRIVAL

Cru ‘Cairanne’: The Birth Of A New Cru In Southern Rhône

Cairanne picked up Cru status in 2016, and with the stroke of that bureaucratic pen, no longer had to label itself a Côtes du Rhône Villages. Found east of Orange, the soils of Cairanne are predominantly built of alluvial limestone from several local rivers and streams; red, iron-rich earth over sandstone bedrock is also found throughout the appellation. Topography ranges from the glacial plateau to the south of the town to the slopes of the Dentelles de Montmirail foothills to the north and west.

“This new appellation status was only made possible thanks to the passion, determination and high expectations of a bunch of local enthusiasts,” says Denis Alary, president of the local winegrowers syndicate, told Wine Spectator. “No decision could better illustrate Côtes du Rhône-Villages dynamism.”

Cairanne is often called ‘the gateway to the Southern Rhône’, combining the typically northern Syrah grape with the much heat-loving Grenache and Mourvèdre. The Mediterranean is dry with plenty of sunshine, and most importantly, vineyard health is heavily influenced by the Mistral wind.

Domaine Alary

Cru Cairanne

Denis Alary of Domaine Alary considers himself a perfectionist as well as a grand idealist; his seventy acres of vineyard, entirely in Cairanne, is where he goes to relieve the stress that accompanies the loftiness of his ambitions …

“Alone,” he says: “Without a cell phone.”

As he took over the estate from his father Daniel, the oenologist is now passing responsibility to his son Jean-Étienne who brings an international reputation to this dry, dusty corner of France, having vinified at New Zealand’s Seresin, Australia’s Henschke and in France at Confuron-Cotetidot in Burgundy.

Domaine Alary ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2020 Cairanne ($23)

Domaine Alary ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2020 Cairanne ($23)

From old vines grown on the terraces of the Dentelles de Montmirail; grapes are hand-harvested separately, sorted and a separate vinification of each different grape variety is made. Bottled without fining, the wine shows profusion of black fruit flavors and soft spices on the nose and a rich full-bodied palate sustained by a mineral touch.

A Rhône With Substance, But No Pretense: Buy A Dozen For $159

Cave de Cairanne Chantecôtes ‘Les Terres Vierges’, 2019 Côtes du Rhône (A Dozen for $159)

Cave de Cairanne Chantecôtes ‘Les Terres Vierges’, 2019 Côtes du Rhône (A Dozen for $159)

First, the difference between a ‘cave’ and a ‘domaine’: Created in 1929, the Vaucluse-based Cave de Cairanne is a collective of 65 winemakers who work over 1300 acres of vines in the Côtes du Rhône, Côtes du Rhône Villages, Villages Plan de Dieu, Cru Cairanne and Cru Rasteau. Chantecôtes is located in Sainte Cécile Les Vignes; the wine is 50% Grenache, 40% Mourvèdre, 10% Syrah showing macerated raspberries, a round and racy palate filled with spice and smoke.

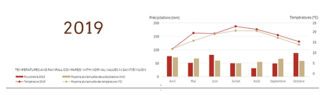

Southern Rhône Vintage Journal

2021 – Classic and Fresh

After six blessed harvests in a row, 2021 brought earth back to earth: Temperatures were unpredictable throughout the growing season, without heat spikes, and random thunderstorms later in July served to test vignerons, including a torrential downpour in mid-September right at harvest-time. Early-budders like Syrah, having been jeopardized by spring frost and the late-ripening grapes also found themselves under threat. Despite this, Mourvèdre, Cinsault, and Carignan fared well, while the quality of Grenache was mixed, some of it (almost unaccountably) particularly good. The best of 2021 wines focus on red rather than black fruit, on lean but elegant tannins rather than any attempts to overcompensate with an ambitious extraction regime or indulgent use of oak.

2020 – Silky and Tender

Fingers were crossed after a brief frost followed an early bud-break, but damage was light; flowering began in mid-May, two weeks earlier than 2019. Amenable conditions continued with hot weather from June, July and August, with the Mistral causing a bit of early damage, but ultimately breathed freshness over the vines all summer. A period of drought culminated in temperatures that peaked at 107°F on August 1. As might be expected, harvest came early, and overall, 2020 will be remembered as one of Southern Rhône’s finest. Sophie Armenier of Domaine de Marcoux (Châteauneuf-du-Pape) comments, “The maturity, the degrees of ripeness, the quantity and the sunshine—everything just came together!”

2019 – Rich and Balanced

Southern Rhône kept a nervous eye on heavy winter rains but in spring, precipitation remained at normal levels. The Mistral, which had been disquietingly calm in ’18, blew strongly in January and February, drying the leaves and removing concerns about mildew. Pleasant weather graced both March and April, the Mistral came back with a vengeance at the beginning of May, resulting in a few damaged leaves but otherwise aerating the vineyards and keeping the vines healthy. An even flowering in late May followed by a successful fruit set in June suggested, much to the growers’ relief, a vintage where yields would be normal. Then came the heatwave, with temperatures as high as 111°F in June, without much nighttime respite. With the lack of rain, this might have proved disastrous but for the high winter rainfall which had filled underground water reserves.

2019 is considered a heat-wave vintage in the Southern Rhône. Those who managed the vines correctly during the excess temperatures of the summer made superlative wines since the hot and dry conditions resulted in small berries with intensity and—crucially—freshness, thanks to the concentration of the grapes’ natural acidity. Growers who worked organically and biodynamically did especially well in ’19, as their vines are so well adapted to manage nature’s whims.

2018 – Supple and Perfumed

2018—largely remarkable throughout France—was hit and miss in Southern Rhône. Although the winter and spring were wet and mild and further rainfall in June caused difficulties with mildew throughout Southern Rhône. Producers sprayed, but a large amount of the crop was still lost, and Grenache, the south’s mainstay grape, is particularly prone to rot and the result was devastating. Winemakers who typically used Grenache as a dominant component of their blends had to shift the focus onto others, chiefly Mourvèdre. Eventually, the damp weather dried up and a hot, dry summer took its place, and by the time it came to harvest, temperatures were high and producers had to work quickly when managing the grapes.

The wines tended to be more densely concentrated than typical with strong fruit flavors and structure. The reds of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Vacqueyras and Gigondas were especially good. The whites suffered slightly from low acidity but still had good fruit character and are generally best suited for early drinking.

- - -

Posted on 2024.03.05 in Gigondas, Cairanne, Côtes-du-Rhône, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Southern Rhone | Read more...

Champagne Haute Couture: Jean-François Clouet, An Outstanding Practitioner of Pinotism, Stitches Together Bouzy’s Finest Parcels into Grand Expressions

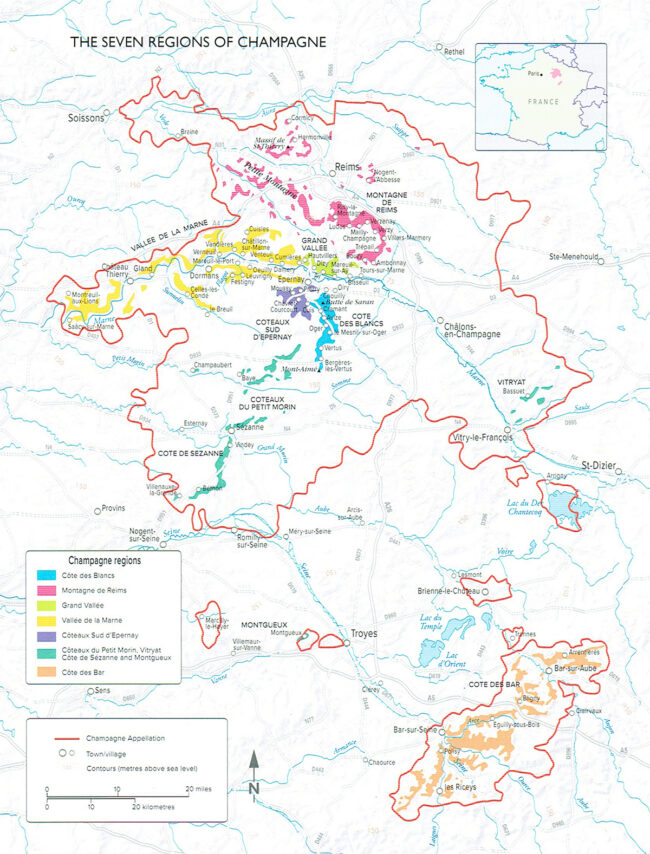

In any assemblage, individual grape varieties will find their niche; each performs according to its purpose and potential, whether it is power, perfume or polish. In Champagne, the Big Three—Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Meunier—jockey for position in the hearts of Chefs de Cave, and although quality depends on location, the ability to eke out or find these locations is an indispensable tool in the belt of vignerons and the pinnacle of Champagne as an artform.

Jean-François Clouet, who was not only born and raised in Bouzy, but still lives in the 18th century village house built by his ancestors, is an example of this ideology at its finest. He says, “The vineyards are like beautiful fabrics, each one contributing textures and colors that once assembled, are transformed into a designer gown. Successfully pieced together, it is Haute Couture.”

The following wine selection represents Clouet’s slice of Champagne, a cellar where Pinot Noir rules but does not monopolize; it is terroir with the standing and privilege of its winemaker, and when it comes to Pinot-based Champagnes, an Eden for expression.

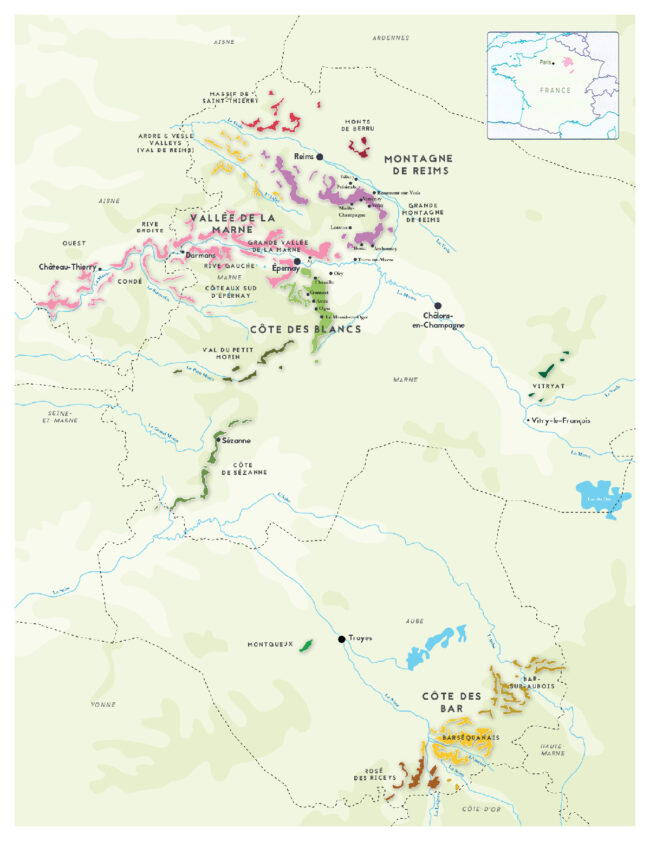

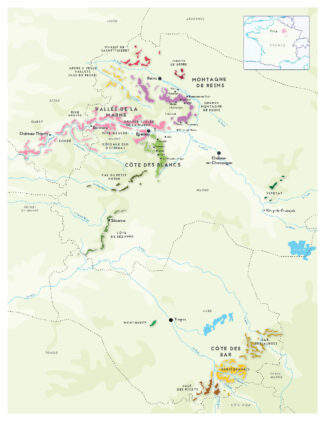

The Montagne de Reims: Pinot Noir Country

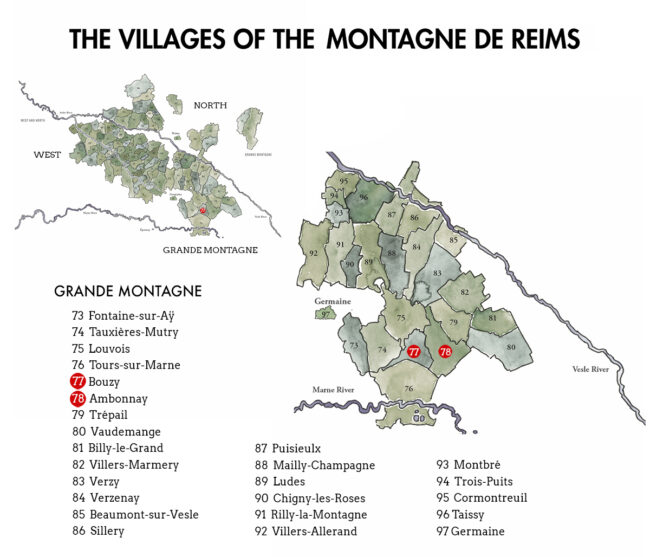

Located between Reims and Épernay, the Montagne de Reims is a relatively low-lying (under a thousand feet in elevation) plateau, mostly draped in thick forest. Vines find a suitable home on the flanks, forming a horseshoe that opens to the west.

So varied are the soils, topography and microclimates here that it is not possible to speak of the region in any unified sense. Grande Montagne de Reims, which contains all of the region’s Grand Cru vineyards, covers the northern, eastern and southern slopes of the viticultural area, and Pinot Noir plantings dominate at 57%, followed by Chardonnay (30%) and Meunier (13%). Its vineyards face a multitude of directions, and soil type varies by village, giving rise to a breadth of Pinot Noir expressions, as well as exceptional Chardonnay.

To the west, the Grande Montagne de Reims gives way to the Petite, whose bedrock is chalk, but softer than the chalk found further south on the Côte des Blancs. This sort, called ‘tuffeau’, is an extremely porous, sand-rich, calcium carbonate rock similar to what is found in wine regions of the middle Loire Valley.

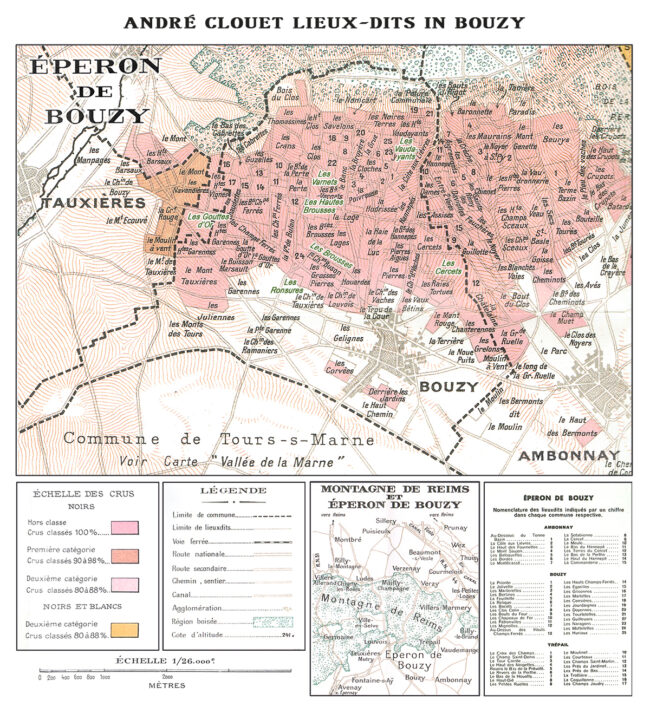

Grand Cru Bouzy: The Epicenter Of Pinot Noir

A village known for its alcohol production named Bouzy? Almost as perfect as its situation on the south-facing side of the Grande Montagne de Reims. This exposure is ideal for ripening Pinot Noir, as its sister village Ambonnay—less than half a mile away—can also attest. Chalky soils provide stimulating freshness as well as housing the deep, cool cellars essential to aging Champagne.

Bouzy has more vineyard acres than citizens (924 to 850) and 87% of the former are Pinot Noir. On the now-defunct ‘échelles des crus’, Bouzy was rated 100%, which make it a Grand Cru village. In recent years, more emphasis has been placed on individual named-sites, either vineyards or portions of vineyards; each lieu-dit is said to possess its own personality which may be exhibited as such, or blended with the others to highlight specific qualities.

The Rare And Demanding Blancs de Noirs

All Champagne is food wine, but not many are ‘gastronomical.’ Meaning, of course, that the ethereal qualities of effervescence, along with high levels of acidity and a small amount of sugar, complement elements in almost any food, from simple poached salmon to red-hot Thai. But few Champagnes are powerful enough in aroma and palate potency to assert themselves as equals in complexity to gourmet dishes.

Many Champagnes are simply about the bubbles; in Blanc de Noir, we see the true emergence of Champagnes that are about great wines that happen to have bubbles.

Blanc de Noirs is made from Pinot Noir, Meunier, or both. The former brings bouquet and body; the latter, supple fruit and roundness. Both grapes, of course, have white flesh and are generally used to make white wine. With Blanc de Noir, a period of maceration on the skins allows the juice to soak up color, and with it, some of the character we associate with Burgundian Pinot Noir—especially, the ability to mirror qualities found in the particular soil in which it grows.

Upon release, a well-made Blanc de Noir is characterized by mouthfeel—a rich and structured texture—but perhaps even more so, powerful aromatics reminiscent of stone fruits, spices, honey, mocha, smoked wood and even a touch of leather. With vintage Blanc de Noir, allowed cellar time, tertiary notes emerge—coffee, cocoa, dried cherry and more mature yeast flavors of brioche and toast.

Champagne André Clouet

Haute Couture Viticulture

In the imagination of most casual drinkers, Champagne is typified by the Grandes Marques, and especially, the Cuvée Prestige bottles. 24 names have enjoyed a marketing monopoly for many decades; brand loyalty, as in all commodities, is built on reputation and unyielding allegiance.

Somewhat less prominent are Champagne’s grower-producers; farmers who make wine. And compared to the Les Grandes Marques (Billecart-Salmon, Bollinger, Krug, et al), Champagne André Clouet has been around longer.

The Clouet family traces its Bouzy roots to 1492 and at one time was the official printmakers for the court of King Louis XV; the classically pretty labels that grace their Champagne bottles today pay homage to their aesthetic history. Clouet grapes are sourced exclusively from 20 acres of coveted mid-slope vineyards in the Grand Cru villages of Bouzy and Ambonnay.

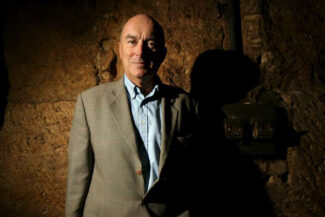

Jean-François Clouet

Born and raised in Bouzy, Jean-François Clouet still lives in his family’s 18th century home; with inimitable wit, he refers to himself as ‘a combination of winemaker and circus ringmaster.’ In fact, the French refer to him as ‘Chef de Cave’—the cellar master. He is arguably the region’s most qualified historian and insists that, without acknowledging the role that the past has played on his winemaking decisions, you can’t truly appreciate his wines.

“To understand Champagne as a whole you need to understand its political history,” he says. “Attila the Hun, the Crusaders, the Templars and Marie Antoinette have all walked here; the birth of the monarchy and the Battle of the Cathalunian Fields took place nearby. In 1911, my great grandfather designed the label that graces our bottles today; I like the idea of the work of human hands in pruning, performing the same actions as my grandfather and even the Romans, who planted vines here 2000 years ago.”

Champagne André Clouet ‘Silver’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut Nature ($51)

Champagne André Clouet ‘Silver’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut Nature ($51)

Clouet’s ‘Silver Label’ Champagne is made entirely with Pinot Noir from the Grand Cru village of Bouzy, mostly from the 2010 vintage (so that it has a lot of age and complexity to it already). While this cuvée has no dosage, it was aged in a former Sauternes barrel and bottle-aged for longer than the standard, resulting in additional richness. The wine displays notes of brioche and cream with buttered pastry, citrus, and a lightly oxidized apple note.

*click photo for more info

Champagne André Clouet ‘Silver’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut Nature ($99) 1.5 Liter

Champagne André Clouet ‘Silver’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut Nature ($99) 1.5 Liter

A little bit of sugar is unnecessary to help this medicine go down, but a smaller ratio of cork to vino is definitely beneficial. The magnum version of the Silver Label.

*click photo for more info

Champagne André Clouet ‘The V6 Experience’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut ($58)

Champagne André Clouet ‘The V6 Experience’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut ($58)

According to Jean-François Clouet, “Pinot Noir does not mature directly, in linear fashion. Upon reaching its sixth year, it passes into a phase known as ‘The Whirlwind.’ Propelled by an unseen force it reaches outward, taking on another dimension. The wine becomes charged with energy and vibrations.”

V6—with a rocket on the label—refers to this mysterious sixth year; the wine is a blend of 80% Pinot Noir aged between 72 and 90 months on the less and 20% Pinot from the solera. It is dosed at 5 gram per liter, based on a liqueur of barrel-aged Chardonnay and refined sugar.

*click photo for more info

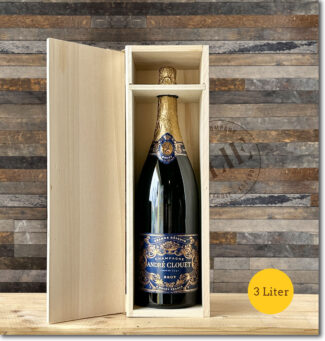

Champagne André Clouet ‘Grand Réserve’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut ($370) 3 Liter

Champagne André Clouet ‘Grand Réserve’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut ($370) 3 Liter

100% Pinot Noir from Bouzy. There’s nothing poetic about the term ‘3 liter’, but in Champagne parlance, this is a Jeroboam. It shows fresh, fine aromatics of apricot and yeast with a fruit-intense palate and a chalky-minerality and salty finesse on the finish with a nice jolt of lemony acidity.

*click photo for more info

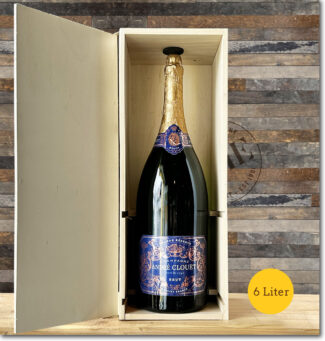

Champagne André Clouet ‘Grand Réserve’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut ($650) 6 Liter

Champagne André Clouet ‘Grand Réserve’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut ($650) 6 Liter

Who’s your daddy? 6 liter is a Methuselah—not the largest bottling format made in Champagne, but the biggest that mere mortals are likely to encounter.

*click photo for more info

Champagne Andre Clouet ‘No 3’, Grand Cru Bouzy Rosé Brut ($58)

Champagne Andre Clouet ‘No 3’, Grand Cru Bouzy Rosé Brut ($58)

92% Pinot Noir, 8% vin rouge from Bouzy; the ‘3’ represents the style of the wine on an odd Clouet scale (inspired by Coco Chanel) where 1 is the lightest wine and 10, the richest. Driven by the chalky minerality of the terroir, the wine offers seductive notes of wild strawberry, raspberry, pomegranate, cherry blossoms, fresh red and pink flowers, crushed chalk, and orange zest.

*click photo for more info

Champagne Andre Clouet ‘No 3’, Grand Cru Bouzy Rosé Brut ($110) 1.5 Liter

Champagne Andre Clouet ‘No 3’, Grand Cru Bouzy Rosé Brut ($110) 1.5 Liter

The magnum format of the above.

*click photo for more info

Champagne d’Auteur: Deeply Rooted, Daringly Innovative

It’s an interesting perspective: Terroir, not only as a sense of place, but as a sense of self. But of all the various elements that combine to make a wonderful bottle of wine—soil and sunshine, rain and rootstock—perhaps the most significant touch is the human one. Give two winemakers identical grapes, and they will make two different wines.

Says Jean-François Clouet, “A signature wine is one which expresses the philosophy or personality of a winemaker working in conditions of freedom and creativity. When surrounded by high quality fruit, and when dedicated to small volume production, the hand of the winemaker will be very present. Such a professional is free to play according to his own criteria, pampering the wine and trying methods that is, in many cases, outside the rules and production guidelines.”

Champagne Andre Clouet ‘Spiritum 96’, Grand Cru Bouzy Rosé Brut ($81)

Champagne Andre Clouet ‘Spiritum 96’, Grand Cru Bouzy Rosé Brut ($81)

“Rosés are usually enjoyed while they are still young and fresh,” says Jean-François Clouet. “But I was looking for that complexity and fullness that exceptional wines acquire only after a very long maturation. I didn’t want to offer a rosé that had merely aged well; I wanted to combine the freshness and youth of a rosé wine with the essence of a great vintage. The key element in accomplishing this feat was going to be the liqueur!”

That goal led Clouet to use a concentration half that of a classic liqueur, giving the wine a final proportion of 88% Grand Cru Pinot Noir, 9% Rouge de Bouzy 2018 and around 3% Liqueur de Millésimé 1996.

*click photo for more info

Champagne André Clouet ‘Cuvée 1911’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut ($81)

Champagne André Clouet ‘Cuvée 1911’, Grand Cru Bouzy Brut ($81)