Rosés Deserve To Live A Little: 2021 Rosés in Full Bloom, Show Character And Dimensions With Two Years of Maturity … 13-Bottle Pack $299 (Limited)

Any remaining stigma attached to rosé remains within the dark soul of the stigmatized; those of us on the right side of wine appreciation understand that rosé is enjoying the fruits—quite literally—of its historical labor. This is especially true in France, where the past several decades have seen rosé coming into its own.

Since 2000, white wine sales in France have plateaued while rosé’s have doubled; over that same timespan, red wine has declined in popularity at such a staggering rate that even if rosé does not win over a single new fan, it may well surpass red wine sales in France in the future.

As a springboard to spring, we will offer a fresh look at this old style through a series of French rosés that span the country from north to south in a 13-bottle package for $299.

Start With Red Grapes

Of the five thousand or so red wine grapes on the planet, the number that are unsuitable for making rosé is precisely zero. And yet, in France, more than 40% of rosé production comes from Provence—an appellation that alone accounts for more than 5% of rosé production worldwide. And in Provence, wine production is dominated by four grapes: Cinsault, Grenache, Mourvèdre and Syrah. The other rosé-producing appellations (as can be surmised) use the red grapes best suited to their terroirs.

Often considered the benchmark rosé in France, Provence has four appellations that each yield distinct wines; Coteaux d’Aix en Provence allows Cabernet Sauvignon to be added to the blend and this results in arguably the most structured rosé from the appellation.

In Bordeaux, Cabernet’s ancestral and spiritual ground zero, the rosé tradition is less pronounced; the AOP for pink production is slightly under nine thousand acres, about half the area for white and a fifth that of red. In Bordeaux, however delicious, rosé is definitely an afterthought. Unsurprisingly, the pink wine is also made from Merlot and Cabernet Franc.

Loire makes its own claim on the style, and is certainly the preference of many. Rosé de Loire and Val de Loire cover Anjou and Touraine, where—taking advantage of the cool climate—the quality is uncompromised; lightly textured, immediately drinkable with raspberry and red currant flavors. Anjou rosés, grown near the Atlantic, are made from Grolleau, Gamay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Malbec and Pineau d’Aunis.

From the icy limits of the north to the sweltering extremes of the south, styles of rosé are determined by many factors but there is certainly a strong case to made for them all.

Making A Rosé With The Capacity To Age, To Evolve, To Stand Up To Food

Even rosé’s most ardent fans may think of it as fun and festive springtime beverage; a crisp quaff meant to be consumed chilled within a year or two of vintage, and for the most part, they are not wrong.

There is a second style, however—one deserving not only of notice, but of understanding: The age-worthy rosé.

All wines have a unique dynamic created by a combination of terroir and target. In other words, a winemaker is bound by soil but not by motive; a number of factors go into the rather complex process of creating a rosé, beginning in the field and carrying through to the cellar. In order to create a wine that has the capacity to mature and improve, decisions are often made before the first vine is planted. Some grapes seem to have a natural affinity for aging—acidity and tannin levels are a large part of it, and so is a susceptibility to noble rot, since a concentration of sugars acts as a natural preservative. In making rosé, neither palate-parching tannin nor botrytis are particularly desirable, but acidity—in balance with natural fruit-forward dryness—is key.

So is having a full, unadulterated, un-doctored body: According to Nicole Rolet of Chêne Bleu in Vaucluse, “Some love-’em-and-leave-’em rosés are made with additives like tartaric acid to achieve the pale color and crisp flavors. That’s the stuff that’s generally going to condemn your wine to a short shelf life. It separates out over time, and the wine will fall apart and lose its aging potential.”

The inconvenient truth, however, is there are no surefire indicators of which rosés are meant to improve with age and which are meant for tonight; color can fool you and so can price; both are indicators that the product may be suited for the long-haul, but is not reliable enough to be fail safe. Color of the bottle may actually be a better gauge than color of the varietal since a producer will not package a seriously-structured rosé in a clear bottle.

The best strategy is to trust your purveyor, so naturally, you can safely assume that the wines offered below are the product of winemakers who took time and care to craft their wares, whenever you choose to drink them.

The 2021 Vintage: A Moment To Celebrate Classical Freshness And Moderate Alcohol Levels?

Something that can be said for certain about Vintage 2021 in France: Every region except Provence registered an output decline. Yields were 13% lower than the average of the last six vintages and 20% lower than the 2020 harvest, while the hardest hit AOPs (Loire Valley, Burgundy, Savoie and the Jura) were down 34% over 2020. This is the result of the worst French frost-related agricultural disaster since systematic record-keeping began in 1947, with 98% of the country affected and the wine industry given a particularly brutal wallop. Neither did the summer do its part; it was wet and cool in the north, dry and hot in the south.

And now the silver lining: Low yields may be a financial hardship on wineries, but they can be a quality godsend for consumers. Cool weather often leads to enhanced acidity (freshness) and lower sugar content, translating to lower alcohol-by-volume.

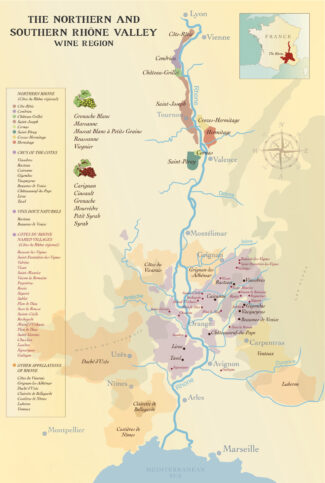

THE SOUTHERN RHÔNE

So dark in color are some of the Southern Rhône’s most celebrated rosés that they nearly defy the ‘blush’ concept. Of the vivid ruby tones found in Tavel, for example, Thomas Giubbi (co-president of the Syndicat Viticole de l’Appellation Tavel winemakers association) said, “We think of our wines as light red wines.”

But that isn’t fair to the category. In its very soul, rosé qualifies as neither red wine nor white wine. It may be (although rarely is; the practice is frowned upon) a blend of the two, but in nearly all cases, it is produced by crushing red-skinned, white-fleshed grapes and allowing a period of maceration lasting from a few hours to a couple days in which the juice is ‘dyed’ to a specific level; alternately, there is méthode saignée, which is essentially fermented free-run juice from red wine pressings.

Gigondas

Like nearby Châteauneuf-Du-Pape, Gigondas depends heavily on Grenache. Based on appellation laws, both the reds and the rosés must be made from up to 80% Grenache, with at least 15% comprised of Syrah and Mourvèdre. The grapes are grown at a higher elevation than Châteauneuf’s, often in terraced vineyards threaded with limestone under the looming Dentelles de Montmirail, with rocky, sandy, free-draining soils on the flatter, lower-lying land to the north and west. Although rosé only accounts for a scant 1% of the production in the entire appellation, it tends to be noteworthy stuff—serious and gastronomic a wine that recalls the rosés of yore that drank well into the years that followed.

1 Domaine Saint Damien, 2021 Gigondas Rosé ($33)

1 Domaine Saint Damien, 2021 Gigondas Rosé ($33)

Spreading over 112 acres, of which around 40 are in Gigondas, Domaine Saint Damien is the brainchild of Joël Saurel and his son Romain, who have lifted the estate—named for the patron saint of doctors—from humble roots to becoming one of the most reputable domains in Southern Rhône. This especially true in his superlative Gigondas, where fruit is drawn from the lieux-dits of Le Gravas, Pigières, La Louisiane, Les Souteyrades, La Moutte and La Tour.

80% Cinsault (planted in 1970) and 20% Syrah (planted in 2000) in the organically-farmed lieu-dit of La Moutte, this small production wine undergoes cold maceration for six hours followed by slow pneumatic pressing and fermentation in stainless steel tanks with occasional lees stirring. Delicately tinted, it shows rose petal, honeydew, lychee, pineapple and garrigue with a hint of pepper and crushed rock on the finish.

Côtes-du-Rhône

Côtes-du-Rhône is one of the largest single appellation regions in the world, covering millions of acres and producing millions of bottles of wine of varying degrees of quality. In Southern Rhône, it encompasses the majority of vineyards and includes hallowed names like Gigondas, Vacqueyras and Châteauneuf-du-Pape. The latter wines prefer to use their individual, highly specific ‘Cru’ names, but the truth is, many generic Côtes du Rhônes may come from plots just outside official ‘Villages’ boundaries—some only across the road or a few vine rows away from top vineyards—and among them, you can find wines with nearly the same level of richness at a fraction of the cost.

2 Domaine Les Grands Bois, 2021 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($16)

2 Domaine Les Grands Bois, 2021 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($16)

If more sommeliers became vignerons, the world might see more low-yield, unfiltered gems like those of Marc Besnardeau, who worked as a wine steward in Paris before following his dream into the vineyard. With wife Mireille Farjon, he took over Domaine Les Grands Bois, whose vines were planted in 1929 by Mireille’s grandfather. The estate is well-situated between St. Cecile and Cairanne, and after selling initially to négociants, the couple began bottling at the estate in 1997. They replanted some fields with Syrah and Mourvèdre, bought new vineyards, and expanded their holdings to its current size, 116 acres spread across seven communes: Sainte Cécile les Vignes, Lagarde-Paréol, Suze la Rousse, Tulette, Cairanne, Rasteau and Travaillan.

60% Grenache, 30% Syrah and 10% Carignan grown on chalky clay and harvested from vines ranging in age from 15-60 years. The wine shows black raspberries, cassis and clementine in a spicy package that highlights anise and honey up front, and with aeration shows deeper savory notes of fresh earth, mushrooms, wildflowers and crushed stone.

3 Domaine La Manarine, 2021 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($22)

3 Domaine La Manarine, 2021 Côtes-du-Rhône Rosé ($22)

Created in 2001, Gilles Gasq established both the winery of Domaine La Manarine and the vineyards on a plateau northeast of Orange within the commune of Travaillan. He has expanded his holdings ever since, and now works with over eighty acres situated largely on ‘Le Plan de Dieu’—a terroir universally heralded for its deep, layered soils consisting of more than 60% hard limestone ‘galets’ which giving a unique minerality to the wines. Gasq says, “Our climate is typically Mediterranean: Relatively hot and dry with rains coming in the form of thunderstorms in late August; this helps provide the vines with the water necessary to finish the maturation process. Grenache is our main grape variety as it performs particularly well on this type of soil and gives wines more elegance and aroma than is otherwise common.”

60% Grenache, 40% young-vine Mourvèdre and 10% Syrah produced solely via direct-press and aged in stainless steel and concrete vats on fine lees prior to being bottled in the early spring following harvest. It is a friendly wine, full of spring berries and pink flowers with a fresh acidity that makes it a refreshing quaff as well as a potentially age-worthy bottle.

Ventoux

Ventoux is a large wine region in the far southeast of the southern Rhône, 25 miles northeast of Avignon and bordering Provence. Covering 51 communes, the vines are planted on the western slopes of Mt. Ventoux, a sort of ‘stray’ Alp removed from the range and towering over the landscape for miles around. Ventoux terroir and varieties are typical for Rhône, although noteworthy are the region’s Muscat produced for table grapes, which has its own AOP—Muscat du Ventoux.

4 Château Valcombe ‘Epicure’, 2021 Ventoux Rosé ($22)

4 Château Valcombe ‘Epicure’, 2021 Ventoux Rosé ($22)

Originally owned by Paul Jeune of Domaine Monpertuis, he opted to sell to Luc and Cendrine Guénard who worked under Jeune’s tutelage during the transition period. They now are proudly independent vignerons with a compulsion to further improve this jewel; their first efforts can be seen and tasted in the 2009 vintage. Certified organic in 2013, the 70 acres of Valcombe are situated in the shadow of the mountain, reaching one thousand feet. Four red grape varieties (Syrah, Carignan, Grenache and Cinsault) balance four white grape varieties (Clairette, Grenache Blanc, Roussanne and Bourboulenc); many vines over sixty years old, although parcels of Carignan and Grenache were planted in 1936. Soils are essentially limestone covered with the area’s famous galets, although deep in the subsoil, an unusual blue-inflected clay helps define the unique characteristics of Valcombe wines.

Vinified via the direct press method from a blend of 60% Grenache, 20% Cinsault, 10% Carignan and a touch of Clairette; all vines are of an average age of 40 years. It has a rich, focused plush texture with strawberry and peach in the foreground and an earthy and intriguing dose of eucalyptus behind.

Luberon

The list of grape varieties permitted in the relatively youthful Luberon appellation (created in 1988) is long, but Syrah and Grenache dominate plantings and must both be present in reds from here. Mourvèdre is also considered a primary red grape. Rosé represents about half the region’s output, and are generally made from the permitted red grapes, although they may legally incorporate up to 20% of white varieties, primarily Grenache Blanc, Clairette, Bourboulenc, Ugni Blanc and Vermentino.

5 Domaine de La Bastide du Claux ‘Poudrière’, 2021 Luberon Rosé ($25)

5 Domaine de La Bastide du Claux ‘Poudrière’, 2021 Luberon Rosé ($25)

Domaine de La Bastide du Claux was born in 2002 when Sylvain Morey—whose family’s roots in Chassagne-Montrachet goes back 400 years—uprooted. In the hills of Luberon, he chose to transplant some of his Burgundian know-how to Provence’s up and coming appellation. In the heart of the Luberon Natural Park, Morey cultivates a fragmented vineyard spread over 42 acres. Finding Luberon’s rich combination of soils, climates and exposures suited to a number of different grapes, he planted 14 varieties, each location chosen with circumspection. “When I arrived, there were not many growers bottling their own wines,” he says. “The vast majority of the production in Luberon was made by local cooperatives, and many of them valued quantity over quality and began to replant vineyards so that they could produce the maximum amount of grapes possible and save money with machine harvesting. These trends made it possible for me to affordably purchase interesting, low-yielding old-vine parcels that were no longer valued.”

50% Grenache from 55-year-old vines, 30% Cinsault, and 20% and Syrah, from south facing vines around the villages of Peruis and Ansouis. The grapes were pressed directly, the majority without maceration, with a portion of Grenache and Cinsault spending six or so hours on their skins after the pressing. Everything is done in cement and the wine ferments naturally, resulting in a great mineral character that shows its soil influence clearly and offers subtle red fruits and vigorous acidity along with a salty tang that typifies Mediterranean rosé.

PROVENCE

Tucked into the southeastern corner of France, Provence covers 125 miles of coastland—no vineyard in the appellation is more than 25 miles from the Mediterranean. And as suits the French Riviera, 3000+ hours of sunshine annually (paired with strong Mistral winds to keep things dry), allow vines to thrive in a hot, maritime climate without risk of fungal disease. Even so, as conditions become even hotter, a new way of thinking has begun to animate this deeply traditional region: Older varietals like Carignan, Barbaroux and Calitor being replaced by more commercially viable grapes like Grenache, Syrah and even Cabernet Sauvignon, although native standbys Mourvèdre, Tibouren and Vermentino continue to hold their ground.

There are pockets of well-received red and white wines throughout Provence, but the name of the game is pink; 82% of the Provençal output is rosé, nearly all crisply acidic and bone dry and in color, ranging from pale coral when made predominantly from Grenache to more deeply tinted Syrah-based wines. In fact, each shade has an official name based on a color chart developed by the Centre de Recherche and d’Expérimentation sur le Vin Rosé: Peach, Melon, Mango, Pomelo, Mandarin and Redcurrant.

Bandol

Conventional wisdom has taught us that wine grapes fare best in places where nothing else will grow; rocky, water-starved soil on precipitous hillsides make vine roots work harder, ramifying and branching off in a search of nutrients and, in consequence, producing small grapes loaded with character. Cue Bandol, the sea-and-sun-kissed region along the French Riviera, which is not only good country for grapes, it’s good country for the soul. Made up of eight wine-loving communes surrounding a cozy fishing village, Bandol breaks the Provençal mold by producing red wines that not only outstrip the region’s legendary rosé, but make up the majority of the appellation’s output. In part that’s due to the ability of Bandol vignerons to push Mourvèdre—generally treated as a blending grape in the Côtes-du-Rhône and Châteauneuf-du-Pape —to superlative new heights.

6 Château Pradeaux, 2021 Bandol Rosé ($41)

6 Château Pradeaux, 2021 Bandol Rosé ($41)

Situated on the outskirts of the town of Saint Cyr-sur-Mer, directly on the Mediterranean between Toulon and Marseilles, Château Pradeaux has been in the hands of the Portalis family since the French Revolution. In fact, Jean-Marie-Etienne Portalis helped draft the Napoleonic Code and assisted at the negotiation of the Concordat under Napoleon the First. Today, the domain is run by Cyrille Portalis, who continues to maintain the quality traditions of his forbears, assisted by his wife Magali, and their sons Etienne and Edouard. Although vineyards are planted almost exclusively to old-vine Mourvèdre, Château Pradeaux Bandol Rosé is composed of Cinsault as well.

Although the skin contact during a slow, gentle press only lasts about 24 hours, that is plenty of time for the perfectly ripe Mourvèdre to work its magic, and the addition of Cinsault (about half the cépage) creates an ideal structure that will allow this wine to evolve with grace. Layers of wild strawberry, blood orange and an herbal undertow of garrigue unfold beautifully.

Cassis

The entire vineyard area of Cassis is under five hundred acres, but most of the properties overlook the sea, which moderates the heat and creates an ideal climate for vine growing; the commune is known primarily for its herb-scented white wines, principally from Clairette and Marsanne (about 30% of Cassis production is rosé) and despite its name, it does not produce Crème de Cassis.

7 Domaine du Bagnol, 2021 Cassis Rosé ($41)

7 Domaine du Bagnol, 2021 Cassis Rosé ($41)

Sitting just beneath the imposing limestone outcropping of Cap Canaille, 700 feet from the shores of the Mediterranean, Domaine du Bagnol is the beneficiary of the cooling winds from the north and northwest and as well as the gentle sea breezes that waft ashore. Cassis native Jean-Louis Genovesi and his son Sébastien run the 18-acre estate.

Grenache, Cinsault and a touch of Mourvèdre combine to produce a wine that is perfumed with red-currant and strawberry aromas and provides a crisp and refreshing wash of citrus and crushed stone/slate minerality on the palate.

Côtes-de-Provence

The massive Côtes-de-Provence sprawls over 50,000 acres and incorporates a patchwork of terroirs, each with its own geological and climatic personality. The northwest portion is built from alternating sub-alpine hills and erosion-sculpted limestone ridges while to the east, and facing the sea, are the volcanic Maures and Tanneron mountains. The majority of Provençal vineyards are turned over to rosé production, which it has been making since 600 B.C. when the Ancient Greeks founded Marseille.

8 Domaine Gavoty ‘Grand Classique’, 2021 Côtes-de-Provence Rosé ($30)

8 Domaine Gavoty ‘Grand Classique’, 2021 Côtes-de-Provence Rosé ($30)

Roselyn Gavoty (the eighth generation of Gavoty to helm her family’s Roman-era farm; her ancestor Philémon acquired it in 1806) is on the cutting edge of viticulture. Situated along the Issole River in the northwestern corner of the Côtes-de-Provence, surrounded by oak and pine forests, the Gavoty family has worked the land without synthetic chemicals for decades, obtaining organic certification in recent years. The vineyard covers 150 acres in the commune of Cabasse (‘harvest field’ in the old Provençal language). Roselyn says, “Our vines are planted on clay-limestone soil, and produce a majority of rosé by the saignée method, involving bleeding off a portion of red must to create structure and depth.”

‘Grand Classic’ contains Grenache and Cinsault in roughly equal proportions, with Carignan playing a minor role. Rather than being pressed immediately after harvest, the wine macerates for several hours, and the saignée and first-press juice are vinified separately and blended until the wine displays its uncanny equilibrium—racy acidity wed to gleaming fruits and just the right amount of earthiness.

Bouches-du-Rhône

‘IGP’ (Indication Géographique Protégée) is a Europe-wide category that focuses on geographical origin rather than style and tradition, giving winemakers greater stylistic freedom than ‘AOP’ (Appellation d’Origine Protégée). As such, the boundaries of Bouches-du-Rhône are geographical, with the Durance river delimiting the north and the Rhône river making up the western border. The soils of the region tend to be poor, free draining and made up of anything from limestone-clay to gravel and sandstone; the lack of water forces vines to produce more concentrated grapes, leading to more concentrated and flavorful wine.

9 Mas de Valériole ‘Grand Mar’, 2021 IGP Bouches-du-Rhône – Terre de Camargue Rosé ($25)

9 Mas de Valériole ‘Grand Mar’, 2021 IGP Bouches-du-Rhône – Terre de Camargue Rosé ($25)

Mas de Valériole’s eighty-acre vineyards reflect diversity in multiple soil types: sand, clay, limestone, and alluvial loam deposited by the Grand Rhône. The reliably steady mistral wind blowing in from the Mediterranean mitigates the heat and facilitates the domain’s chemical-free approach to farming while ensuring modest alcohol levels in the wines. The property was acquired by the Michel family in the late 1950s and is now run by Jean-Paul and Patrick Michel. Produced from a variety of cépages, including Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, plus crossings like Caladoc (Grenache and Malbec) and Marselan (Grenache and Cabernet Sauvignon) which are particularly well-suited to the Camargue’s climate, Mas de Valériole’s wines combine the breezy freshness of Provence with a sense of wildness and an underlying salinity that is representative of Bouches-du-Rhône.

‘Grand Mar’ Rosé is 100% Caladoc, fermented with indigenous yeasts (unusual for rosé production) in stainless steel tanks to preserve freshness. The wine is enticing with vibrant notes of ruby-red grapefruit and white peach behind crackling acidity—a wine that never met a salmon dish it did not love.

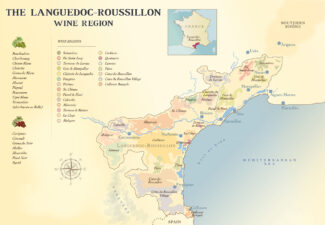

LANGUEDOC-ROUSSILLON

Sun-baked and sensual, threaded with rivers and capped by the mountains of Corbières, Languedoc-Roussillon relies on over a hundred grape varieties to produce more than a third of all French wine. Historically, this wine was copious, inexpensive and rather forgettable—everyday wine for the tables of ordinary people. Since the mid-twentieth century, however, with the advent of irrigation in the foothills and coastal plains of Southern France coupled with improved techniques, the region now boasts fewer vines that produce wines of increasing quality. A jigsaw of soils and a broad swath of microclimates creates ideal terroir for the warm-weather, full-bodied varietals often associated with the Rhône, while sharp diurnal shifts allow for the preservation of aroma and natural acidity, resulting in wines of extraordinary balance. A further plus is that Languedoc-Roussillon’s hot, dry climate discourages the growth of mildew and fungi, making synthetic pesticides and herbicides less necessary. As such, it has become a proving ground for organic and biodynamic producers.

10 Mas Jullien, 2021 Languedoc Rosé ($35)

10 Mas Jullien, 2021 Languedoc Rosé ($35)

Among the early pioneers of the modern ‘Larzac style’ is Olivier Jullien: His forty terraced acres, with two distinct soil types—calcaire and argilles—was established in 1985, and his domain, Mas Jullien, is a paradigm of the region. Having witnessed first-hand Languedoc’s tradition of over-cropping to produce bulk wine, he recognized that the economic plight of local independent farmers may have failed to take advantage of the appellation’s promise. With a degree in enology to shore up his conviction that the area had the potential to produce world-class wine, he showed his iconoclastic hand early by pulling out vineyards and re-planting trees in an effort to restore balance to the local ecosystem. His wines are delightful examples of this balance, imbued with the distinct characteristics permitted by elevation and proximity to the sea.

A saignée rosé made from juice that is bled off the skins of red grapes from Jullien’s vineyards on the Terrasses-du-Larzac. A blend of Cinsault, Carignan and Mourvèdre, though the blend can change from vintage to vintage. Fermentation takes place in stainless steel with native yeast, aging in Stockinger foudres of mixed ages. It is a structured and somewhat wild wine of deep, earthy complexity showing garrigue and wet stone behind strawberry and watermelon.

BORDEAUX

Today, rosé is a serious wine in Bordeaux, but still, ‘serious’ must be viewed on a sliding scale compared to the reds. Even this is an improvement; in days not too long ago, it was not only uneconomical to turn red wine grapes into pink, it was generally only made in weaker vintages, when juice might be bled off reds to make a ‘weak red’ or darker pink or from fruit from vines too young to make viable reds. In 2010, the Bordeaux Wine Board reviewed its marketing strategy and the role of Bordeaux in the international market and started to actively encourage Bordeaux rosé as a means of attracting younger drinkers to old-guard wines. In part, the campaign has succeeded, and sales of rosé (as opposed to ‘clairet’, the darker red version that is often the product of saignée rather than direct-press) have grown. Fresh Bordeaux rosés remain a unique beast in that they have a blue tinge, with no hints of orange-salmon in their youth, although with age, they fade toward this hue.

11 Château La Rame, 2021 Bordeaux Rosé ($24)

11 Château La Rame, 2021 Bordeaux Rosé ($24)

La Rame’s fifty acres overlook the Garonne; they face south and the vineyards are planted in clay-limestone with an exceptional substratum marked by fossilized oyster shells dating from the Tertiary era. Further down the slope, where sandier soils predominate, the estate’s Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot thrive. The property was purchased by the father of the current owner, Yves Armand, at a time when the appellation had fallen out of favor. The family has undertaken to re-establish their Sainte-Croix-du-Mont AOP as an appellation to rival the great estates nearby.

A relatively new addition to the Rame portfolio, the grapes (80% Cabernet Sauvignon and 20% Merlot) are sourced from a five-acre parcel of younger vines on the flanks of a hill that descends towards the Garonne. The wine is produced via the direct-press method and is fermented in temperature-controlled vats for six months before it is bottled. It shows fine aromatic persistence with notes of red currant, raspberry and pear with a hint of banana. About 15,000 bottles are produced annually and only a few thousand are exported to the USA.

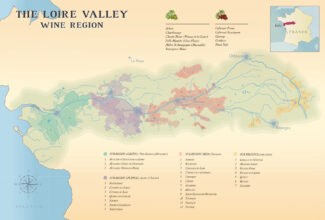

THE LOIRE VALLEY

Rosé de Loire adds yet another dimension to French blush. Extending across the Anjou and Touraine AOPs, it covers about 2000 acres and is responsible for more than a million gallons of rosé every year. Its color lends itself to dramatic descriptors ranging from ‘flamingo pink with a hint of poppy’ to ‘gleaming raspberry pink with a glimmer of violet.’ These wines are generally dry, but there is a subset that is off-dry and another subset, Crémant, that sparkles. There is even a ‘Primeur’ (or ‘Nouveau’) style, a much fruitier wine that is almost entirely free of tannins—a result of being fermented using the Beaujolais method of carbonic maceration. Like the red wines of Loire, the principle grapes used in the rosé are Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Grolleau (Noir and Gris), Pineau d’Aunis, Gamay and/or Pinot Noir. Beyond color, Rosé de Loire is delightful elegance in a glass; Rosé d’Anjou in particular is noted for its reflection of terroir.

Saumur

As a fair representation of the Middle Loire, Saumur—radiating outward from the town center into neighboring administrative departments of Vienne and Deux-Sèvres—is primarily Chenin country, with a strong tradition of producing sparkling wines, for which the geology is particularly well suited. The town sits on a mound of tuffeau—the porous, sandy-yellow rock which underpins several of the central Loire’s top vineyard areas. Many miles of underground cellars have been cut directly into this soft rock, providing a cool, temperature-moderated environment perfect for storing méthode traditionelle wines during their lees aging. The reds, making up around 20% of the output, are built around Cabernet Franc, although Cabernet Sauvignon and Pineau d’Aunis can figure into the blend in minor quantities. Rosé gets afterthought focus and is only around 5% of total output; the appellation for rosé wines ‘Cabernet de Saumur’ has the same borders as Saumur AOP and is reserved for off-dry wines with at least 10 grams per liter residual sugar.

12 Château de Chaintres ‘Les Hirondelles’, 2021 Saumur Rosé ($32)

12 Château de Chaintres ‘Les Hirondelles’, 2021 Saumur Rosé ($32)

The de Tigny family has not only owned this property since 1938, a good number of the vines planted back then are still in production. In 2017, the estate hired Jean-Philippe Louis as cellar master, and he immediately began to transform the vinification philosophy with a precise, intuitive and non-interventionist hand. The property’s tuffeau makes for Chenin of vigorous acidity and penetrating precision as well as transparent Cabernet Franc, which thrives in the heat-retaining sand that covers the limestone, possessing a complexity and longevity that extends far beyond its fresh, finesse-driven profile.

100% Cabernet Franc, pressed directly, fermented spontaneously, and aged in steel with a bare minimum of sulfur. Floral up front with rose petal and geranium notes that meld into strawberry and mandarin flecked with flint over a chalky framework.

Anjou

Anjou sprawls across 128 communes, mostly south of the towns of Angers in the west and Saumur in the east. Monasteries played the largest role in developing Anjou’s wine trade, as each enclave had its own walled vineyard. But it was French royalty who secured the region’s reputation, beginning nearly a thousand years ago when Henry Plantagenet became King Henry II of England. Anjou’s terroir is a matter of black and white: it’s divided into two subsoils as different as day and night. First, Anjou Noir, composed of blackish, dark, schist-based soil along the south-eastern edge of the Massif Armoricain, then, Anjou Blanc, lighter-colored soils made up of the altered chalk at the south-western extremity of the Paris Basin.

13 Château Soucherie ‘L’Astrée’, 2021 Rosé-de-Loire ($30)

13 Château Soucherie ‘L’Astrée’, 2021 Rosé-de-Loire ($30)

Perched on a rise overlooking the Layon river, Soucherie is considered one of the most beautiful domains in Anjou. Roger-François and Pascal Beguinot have transformed 90 acres of limestone, clay and schist into multiple lieux-dits spread across Anjou, Chaume, Coteaux-du-Layon and Savennières. Around the winery, 54 acres are planted on a southern hillside sheltered from the winds; the 11 acres in Chaume contain vines over 70 years old while the four acres in Savennières (Clos des Perrières), loaded with shale, produce wines noted for their minerality. Maître de chai Thibaud Boudignon is leading the charge towards 100% organic viticulture through the principles of ‘agriculture integrée’—a ‘whole farm’ management system intended t deliver more sustainable agriculture by combining modern technologies with traditional practices according to a given site and situation.

The wine is dry and mineral-driven, produced from 70% Grolleau and 30% Gamay planted to clay, sandstone and schist soils. A ‘direct press’ rosé with élevage in cuve and bottling in April of the spring following harvest. The nose of white peach is underscored by herbal notes of dandelion greens and pineapple sage are complimented by a palate juicy with strawberry and watermelon notes.

- - -

Posted on 2024.03.22 in Côte-de-Provence, Rosé de Loire, Anjou, cassis, Bandol, Luberon, Ventoux, Terrasses du Larzac, Gigondas, France, Bordeaux, Wine-Aid Packages, Languedoc-Roussillon, Loire, Provence, Southern Rhone

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Aligote, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Cinsault, Clairette, Corvina, Counoise, Dolcetto, Erbamat, Ferrol, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Gamay, Garnacha, Garnacha Tintorera, Gewurztraminer, Graciano, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malbec, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marcelan, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montònega, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscat, Natural, Niellucciu, Parellada, Patrimonio, Pedro Ximénez, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Pouilly Fuisse, Pouilly Loche, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Riesling, Rondinella, Rose, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sagrantino, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Sciacarellu, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Search