Chalk About Champagne: With a Balance Between Fruit, Finesse and Structure, The Sparkling Chardonnays of Côte des Blancs Are Some of The Most Compelling White Wines Made Today.

“I am tasting stars!”

Dom Perignon’s famous quote, reported to have been uttered upon his first taste of Champagne, is likely apocryphal, but the trio of stars that align in a cold, northerly slice of France that sits on the ‘Seuil de Bourgogne’—the threshold of Burgundy—is not. It is the very-real combination of site-selected soil, grape variety and climate that makes Champagne unique in the world, and so it has been heralded ever since that moment in the cellars of the Benedictine Abbey at Hautvillers, whatever it was that the old monk said.

The soil is the result of eons of erosion, which has left low scarps and slopes that dip toward the center of the Paris Basin; the varying nature of the clay, limestone and chalk gives rise to the characteristics of Champagne’s sub-regions and create unique cradles for each of the main grape varieties, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Meunier. That said, these grapes are like canaries in the mine of wine production, and highly susceptible to the most minute changes in the atmosphere. The recent past has seen both growers and producers alter their outlook on Champagne making and it is a safe bet that more of the same is in the cards for the future.

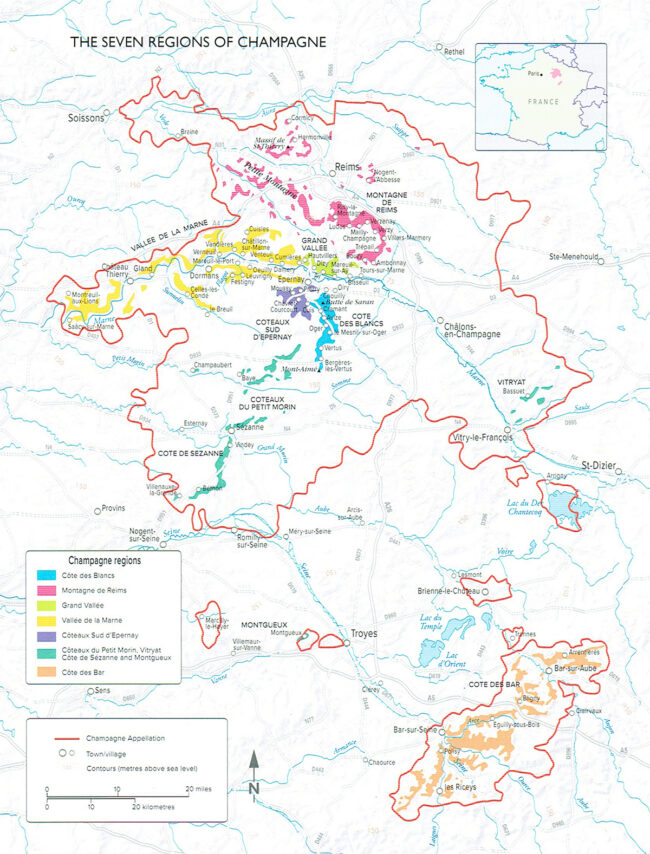

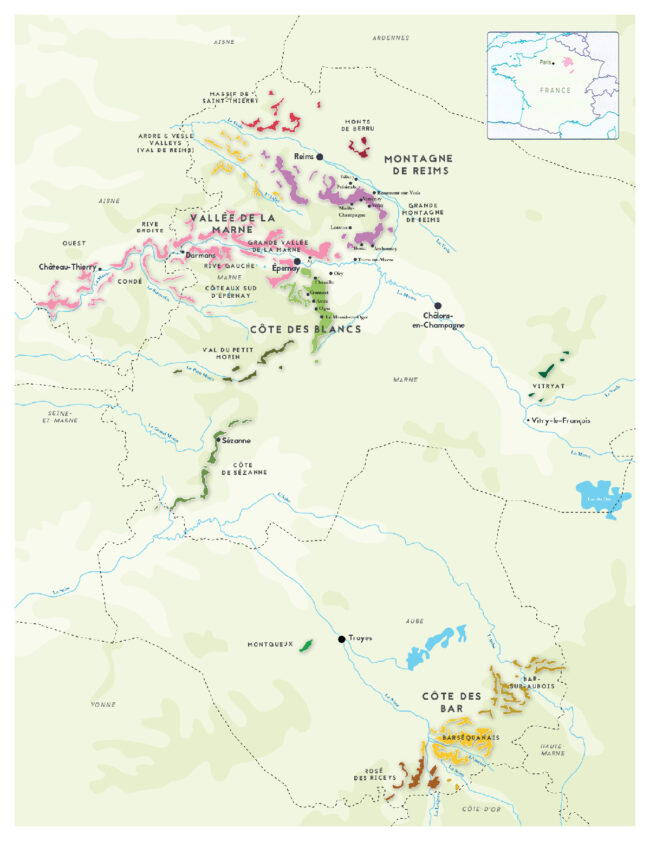

Champagne’s Distinct Sub-regions

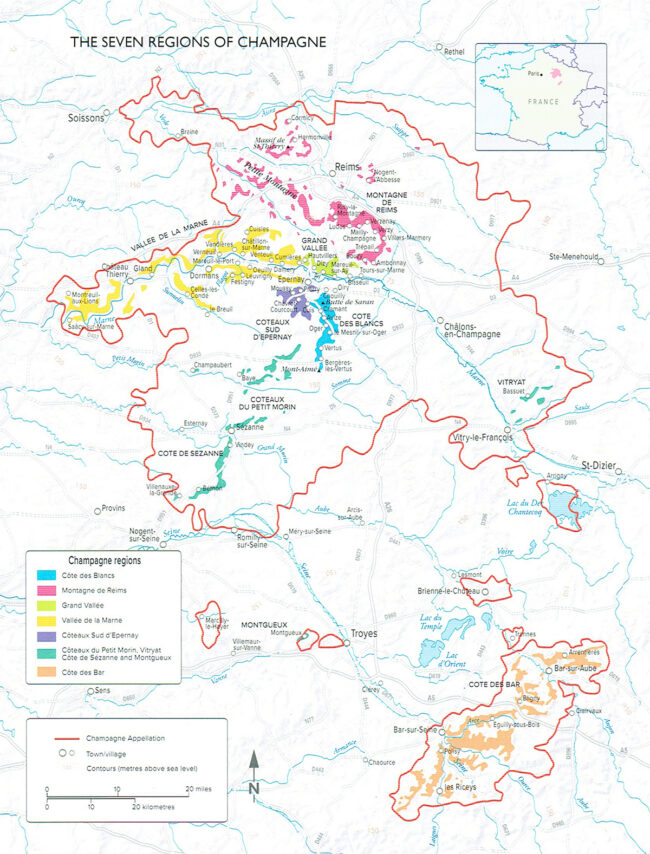

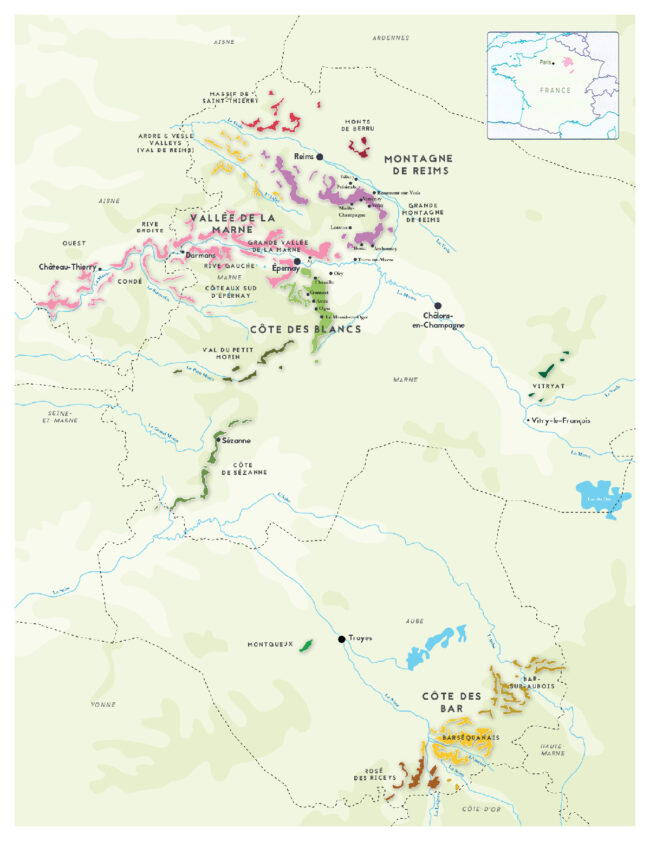

Although a single AOP covers all sparkling wine produced in Champagne, there are several distinct sub-regions, each of which was originally associated with a single grape variety. Of course, geography changes throughout the area, so pockets of Champagne’s three main grape varieties (Pinot Noir, Meunier and Chardonnay) can be found in each district.

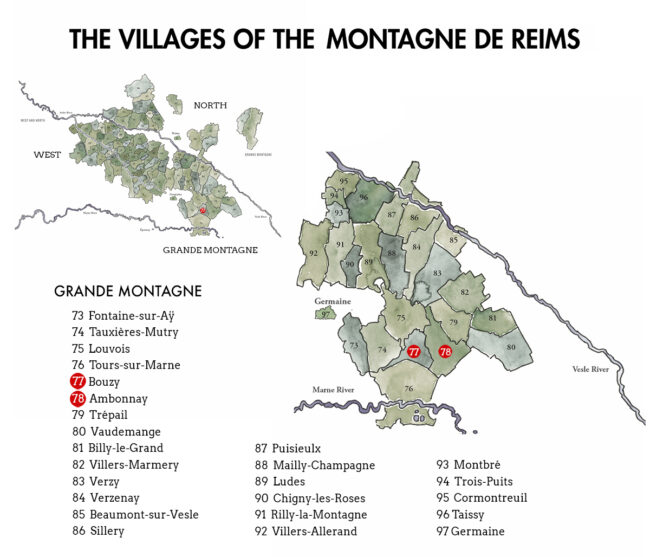

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

The lauded wine writer Peter Liem expands the number of sub-regions from four to seven, dividing the Vallée de la Marne into the Grand Vallée and the Vallée de la Marne; adding the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay and combining the disparate zones between the heart of Champagne and Côte de Bar into a single sub-zone. (For details see Notebook, at the bottom of newsletter.)

Single-Vineyard Champagne: The Return To Prominence Of Vineyard and Viticulture

Whereas the ‘art’ of Champagne is often discussed in terms of expert blending—much as color is added in layers to create a portrait—a Cellar Master uses a pallet of flavors to create synergy, a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. Traditionally, ‘house styles’ have been established over decades (even centuries) and homogeneity—in the best sense of the word—is the goal.

Even vintage Champagne (assembled from a single harvest, though many villages may contribute) should highlight the house approach, since loyal customers expect as much.

So why are site-specific bottlings Champagnes growing popularity? In part because of the rising renown of grower/producers, who are highlighting individual plots of terroir that they themselves have developed. It is trendy (and completely correct) to regard Champagne as wine first and foremost, and as such, individual vineyard expression rather than cookie-cutter (however delicious) house style is simply a new way to view this old standby appellation.

Above all, a single vineyard creates a unique fingerprint of the land beneath the vine, and to a terroir purist, there is no reality more compelling.

The Côte des Blancs

Uninhibitedly Chalky, Chardonnay Thrives Here.

Soil chemistry may be nuanced—acidity combined with alkalinity, macronutrient and micronutrient availability, et al., but its effects on grape growing is profound. The Côte des Blancs sits upon an exceptionally pure chalk bedrock, which combined with mostly east-facing slopes, creates an ideal environment for growing Chardonnay. The resulting wines are unparalleled in poise and finesse.

Even with this overview, the individual villages that pepper the 8000 acres of Côte des Blancs vineyards each bring their own unique gift to the Champagne party. As a result, it is fairly easy to differentiate styles and subtleties between the communes, and broadly, between those of the north and south. Wines from the northern Côte des Blancs villages, with more clay in the chalk, produce richer wines with recognizable weight while those of the south, with lighter topsoils, are piercing, fine-grained wines with a characteristic minerality that is often described as ‘salinity.’

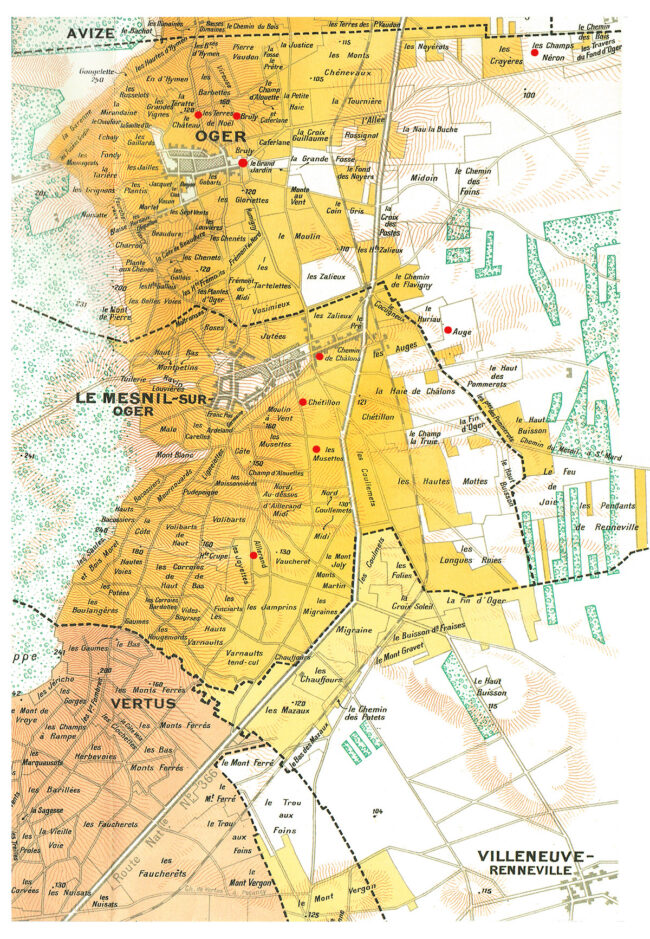

The Grand Cru Villages Of The South: Oger and Le Mesnil-sur-Oger

Oger and its sister commune Le Mesnil-sur-Oger are among the 17 villages that were scored 100% on the now defunct échelles des crus scale, and both have kept their Grand Cru status after the scale was abolished in 2010. Both were promoted from Premier Cru to Grand Cru in 1985 and possess an austerity and potential that very few sites in the entire region possess.

Oger occupies slightly under a thousand vineyard acres on the ‘true’ Côte des Blancs slope south-southeast of Épernay; Le Mesnil-sur-Oger is sightly larger, and both produce exclusively Chardonnay. These wines are renowned for their firm, mineral-driven style which also manages to be elegant and balanced. The differences between the two Grand Crus may be a subject of discussion among fans, but the fact is that most of the variations are the result of producer and vintage as well as the location of the specific vineyard, whether in the slope above and around the villages or below them, on flatter land.

Champagne Domaine Vincey

Until 2014, the Vincey family grew their grapes and delivered them to the local cooperative after harvest, a practice that was the rule rather than the exception in Champagne until fairly recently.

In 2010, Quentin Vincey took over the family’s seventeen acres, and that long-standing tradition fell by the chalky waste side. Today, though he still sells some grapes to small organic houses, he and his wife Marine keep the bulk for themselves. Having converted the property to organic viticulture, the couple claims inspiration from the earth-friendly techniques that have taken much of France by storm, including spraying with essential oils and plant extracts.

“We made our first house-bottled Champagnes in 2014; that year we produced only 4000 bottles, but every year the quantity has increased a little bit,” says Quentin. Marine adds, “We maintain open minds, and learn a lot from tasting wines blind with friends, including wines from other regions.”

Quentin Vincey, Marine Vincey with Martin (cat) and Luna (dog)

Photo: Carine Charlier/Clic & Plumes

Among the best-practices which they now employ is base-wine fermenting in small oak barrels, about eight years old on average, so that the oak does not impart much flavor but is invaluable for allowing micro-oxygenation. “Our Chardonnay, with its high acidity, needs oxygen which it gets through the oak,” says Marine. “We also temper the acidity by picking at a higher sugar level than many other local producers. So, there is never a need to chaptalize.”

The different vineyard plots are kept separate in the barrels during the lees-aging. “We ferment only on natural yeast,” says Quentin. “This is rare in Champagne, where most producers use controlled cultured yeast. We think it offers a smoother taste, although it takes more time to ferment; two months is not unusual.”

Between January and March, the year after the harvest, the couple blind tastes all the barrels. and bottle at the beginning of September, before the new harvest. After a year in barrels, they don’t need to do any filtration, and this further adds complexity. Marine says, “The bottles will stay five years in the cellar before disgorging which is two years longer than the minimum for a vintage Champagne.”

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2018 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Oger Brut-Nature ($89)

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2018 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Oger Brut-Nature ($89)

100% Grand Cru Chardonnay harvested from selected old vines; vinification and fermentation in fût de chêne without malolactic, clarification, filtration and matured on lees for three years. Zero dosage, disgorged January 2022. 4845 bottles produced.

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2018 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Oger Brut-Nature ($189) 1.5 Liter

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2018 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Oger Brut-Nature ($189) 1.5 Liter

Same as above in magnum; only 200 magnums produced.

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2018 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Oger ‘Le Grand Jardin’ Brut-Nature ($117)

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2018 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Oger ‘Le Grand Jardin’ Brut-Nature ($117)

The third release of Vincey’s first lieu-dit wine; the grapes come from a small plot directly behind the Maison, where ideal warmth gives the Chardonnay a characteristic profile of tropical fruit with some candied elements and salt.

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2015 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Oger ‘Le Grand Jardin’ Brut-Nature ($117)

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2015 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Oger ‘Le Grand Jardin’ Brut-Nature ($117)

100% vintage 2015 Chardonnay from an old lieu-dit planted in 1967 with vinification and fermentation in fût de chêne without malolactic, clarification, filtration and matured on lees for three years. Zero dosage, disgorged December 2021. 2024 bottles produced.

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2018 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger ‘Auge’ Brut-Nature ($117)

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2018 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger ‘Auge’ Brut-Nature ($117)

Auge is a tiny lieu-dit, less than three-quarters of an acre, planted in 1971. 100% 2018 Chardonnay with vinification and fermentation done in fût de chêne without malolactic, clarification, filtration and matured on lees for three years. Zero dosage, disgorged October 2022. 1375 bottles.

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2018 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger ‘Chemin de Châlons’ Brut-Nature ($117)

Champagne Domaine Vincey, 2018 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger ‘Chemin de Châlons’ Brut-Nature ($117)

From a half-acre lieu-dit, fermented on indigenous yeasts and aged for 12 months in oak barrel; bottled without filtration or fining. Zero dosage; disgorged July 2023.

Domaine Vincey ‘Vieilles Vignes – Oger & Mesnil-sur-Oger’, 2019 Coteaux-Champenois Grand Cru Blanc ($108)

Domaine Vincey ‘Vieilles Vignes – Oger & Mesnil-sur-Oger’, 2019 Coteaux-Champenois Grand Cru Blanc ($108)

50% Oger Grand Cru, 50% Le Mesnil-sur-Oger Grand Cru old vines; a still wine vinified and aged for 27 months in oak barrels before bottling in December 2021. Only 860 bottles made.

Champagne Pertois-Moriset

When young couples marry, their first order of business is often creating a family. In the case of Yves Pertois and Janine Moriset, who wed in 1951, it was to build a winery. Having both been raised in the business, they set up shop in Mesnil-Sur-Oger and drew fruit from fifty acres of prestigious vineyards split between Côte-des-Blancs and Côte de Sézanne

Today the estate is run by their granddaughter Cécile, who, with her husband Vincent Bauchet, has worked diligently to improve all aspects of the inheritance, technically and ecologically. “The estate works while remaining attentive to the biodiversity that surrounds it,” Cécile maintains. “If the years allow it, no chemical inputs are applied on the vine; the vines are naturally grassed in winter, and in summer the soil is ploughed. All mechanical work is carried out with a 100% electric tractor.”

Vincent Bauchet, Champagne Pertois-Moriset

Vincent adds, “Respecting House legacy, we created a pressing center in 2009. It is equipped with two stainless-steel membrane presses, two thermo-regulated stainless-steel tanks, and a vat room for barrels and big oaks. These facilities contribute to a healthy pressing, a fermentation at controlled linear temperature, a malolactic fermentation deliberately blocked on most of the cuvées, and an aging on fine lees throughout the winter. Our wine is bottled in June/July in order to give the wine time to fully develop in tanks and barrels. The bottles then rest in the cellar, at least 20 months for the main vintages, and much longer other vintages, thus guaranteeing that our wines reflect the unique flavors of their terroir.”

Champagne Pertois-Moriset, 2015 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger ‘Les Hauts-d’Aillerands’ Extra-Brut ($104)

Champagne Pertois-Moriset, 2015 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger ‘Les Hauts-d’Aillerands’ Extra-Brut ($104)

From two plots of Chardonnay within the lieu-dit Les Hauts-d’Aillerands planted in 1997 and 2010 with southerly exposures. Half the wine was fermented in steel tanks, the rest in oak; fermentation lasted seven months followed by 72 months on lees with a final dosage of 2.5 grams/liter.

Champagne Pertois-Moriset ‘Spécial Club’, 2016 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger Extra-Brut ($104)

Champagne Pertois-Moriset ‘Spécial Club’, 2016 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger Extra-Brut ($104)

Pertois-Moriset made this wine to celebrate their return to the Club Trésors de Champagne, a prestigious group of artisan winemakers; it is a blend of their most respected lieux-dits. Vinified 12% in barrels and 88% in stainless steel tanks; 60 months in cellar, and dosed at 2 grams/liter. Production was 6539 bottles, 405 magnums and 50 jeroboams.

Champagne Pertois-Moriset ‘Spécial Club”, 2016 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger Extra-Brut ($299) 1.5 Liter

Champagne Pertois-Moriset ‘Spécial Club”, 2016 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger Extra-Brut ($299) 1.5 Liter

See above; the wine is in magnum.

Champagne Pertois-Moriset ‘Les Quatre Terroirs’, Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Extra-Brut ($66)

Champagne Pertois-Moriset ‘Les Quatre Terroirs’, Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Extra-Brut ($66)

100% Grand Cru Chardonnay; the label’s four terroirs are in Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, Oger, Cramant and Chouilly. The wine is 70% vintage, 30% perpetual reserve, vinified in both tank and barrel without malo. The wine spends 36 months on the lees and is dosed at 3 grams/liter.

Champagne Pertois-Moriset ‘Rosé Blanc Collection’, Grand Cru Extra-Brut ($72)

Champagne Pertois-Moriset ‘Rosé Blanc Collection’, Grand Cru Extra-Brut ($72)

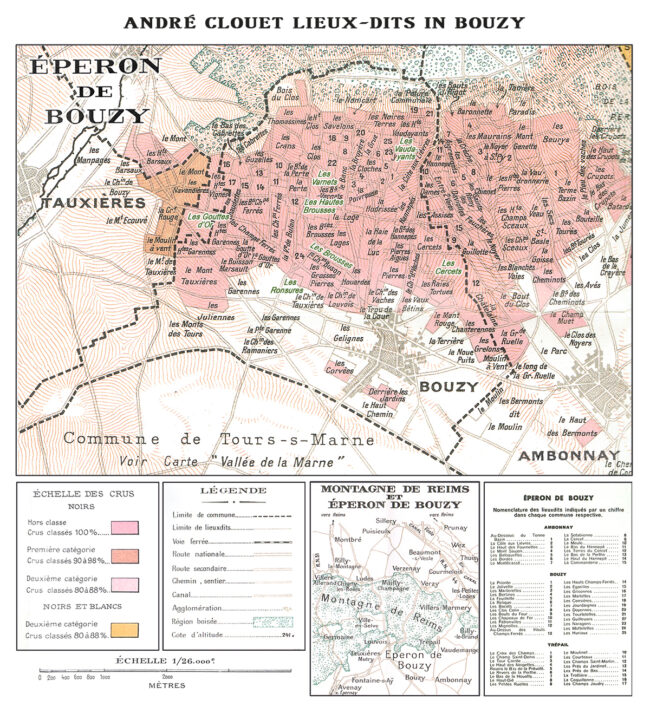

92% Chardonnay Grand Cru and 8% Bouzy Rouge Grand Cru Pinot Noir. The wine is 70% vintage, 30% perpetual reserve, vinified in both tank and barrel without malo. The wine spends 30 months on the lees and is dosed at 3 grams/liter.

The Côte de Sézanne: Côte des Blancs Continuum?

The 1500 acre Côte de Sézanne sits a few miles southeast of Étoge in the Côte des Blancs. Chardonnay accounts for around 75% of the vineyard plantings, but there is a significant amount of Meunier and Pinot Noir grown here. Sézanne wines are known for being among the fruit-forward in the region, but critics point out that this is often a trade-off for finesse.

The terroir of the region differs slightly from the Côte des Blancs; unlike the predominantly chalky soils further north, the soils here are mostly clay and a mixture of clay and chalk. Due to the specifics of the terroir, grapes tend to ripen a little earlier than other regions.

Champagne Pertois-Moriset, 2018 Coteaux-Sézannais ‘Barbonne-Fayel’ Brut ($99)

Champagne Pertois-Moriset, 2018 Coteaux-Sézannais ‘Barbonne-Fayel’ Brut ($99)

This mono-village Vintage Champagne from Barbonne-Fayel in the Côte de Sézanne, a village made famous in Ulysse Collin’s ‘Les Maillons.’ 100% Pinot Noir vinified 80% in stainless steel and 20% in foudre with malolactic blocked. The wine spends three years in bottle on lees and is dosed at 3 grams/liter.

Champagne Pertois-Moriset ‘L’Assemblage’, Coteaux-Sézannais Brut ($263) 3 Liter

Champagne Pertois-Moriset ‘L’Assemblage’, Coteaux-Sézannais Brut ($263) 3 Liter

50% Pinot Noir and 50% Chardonnay from the slopes of the Marne in the Côte de Sézanne, vinified in stainless steel and blended with 30% reserve wine from oak barrels. The wine is aged for a minimum of 15 months and dosed at 1 gram/liter.

Champagne J.L. Vergnon

In this small 12-acre estate in the heart of the Grand Cru village of Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, Didier Vergnon and his son Clément have worked tirelessly toward organic farming, harvesting only balanced and ripe grapes. They have eliminated both chaptalization and malolactic fermentation, and prefer a low or zero dosage. The brilliant winemaker Christophe Constant has been at their side, both as cellar master and now, as consultant.

Didier Vergnon (standing) with Christophe Constant

Of the property, Didier says, “Our domain extends over several terroirs, the majority in Le Mesnil sur Oger, classified Grand Cru, Blanc de Blancs. We also draw from vineyards in Oger and Avize, and also vines in surrounding Premier Cru villages Vertus and Villeneuve.”

Champagne J.L. Vergnon ‘Murmure’, Côte-des-Blancs Premier Cru Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($63)

Champagne J.L. Vergnon ‘Murmure’, Côte-des-Blancs Premier Cru Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($63)

100% Chardonnay, half from Vertus Premier Cru, half from Villeneuve Premier Cru, from 30-year-old vines. Fermented and aged in 50% stainless steel, 50% older 400-liter barrels and bottled with zero dosage. Disgorged June 2019.

Champagne J.L. Vergnon ‘MSNL’, 2010 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger Blanc-de-Blancs Extra-Brut ($130)

Champagne J.L. Vergnon ‘MSNL’, 2010 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Le Mesnil-sur-Oger Blanc-de-Blancs Extra-Brut ($130)

100% Chardonnay from east-facing Les Chétillons and Mussettes vineyard in Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, formerly released under the ‘Resonance’ label. Vinified and aged in steel tanks, aged seven years in the cellar and dosed at 3 grams/liter. Disgorged June 2018. 3222 bottles produced.

Champagne J.L. Vergnon ‘Rosémotion’, Grand Cru Rosé Extra-Brut ($89)

Champagne J.L. Vergnon ‘Rosémotion’, Grand Cru Rosé Extra-Brut ($89)

A scant 2000 bottles of this Grand Cru rosé were produced; 90% Chardonnay from Mesnil s/ Oger, Oger and Avize and 10% Pinot Noir from Mailly Grand Cru. 20% of reserve wine was aged 3 months in oak barrels and 80% of single-year in steel tank. The wine is a delicate Creamsicle color and shows currants and pomelos on the nose, with notes of strawberries, saffron and biscuits reflecting the long aging on lees. Disgorged June 2019.

The Northern Villages Of The Côte des Blancs

Of the notable Cru-level villages in the northern sector of the Côte des Blancs, Cramant covers 870 acres, of which 99.9% are planted to Chardonnay. As the name suggests, Cramant Champagnes are often considered ‘creamier’ than those of nearby Avize, where there is a higher proportion of east-facing slopes. These wines are also more concentrated than those of Cuis, where there is a higher proportion of north-facing slopes and with a more dominating minerality than those in Chouilly.

Chouilly, immediately to the east of Épernay and just south of Marne, is larger at 1300 acres, with slightly more Pinot Noir planted. Champagnes from Chouilly are usually said to be of a rather “rich” style with buttery notes or aromas of tropical fruit, and with less intense mineral character than the Grand Cru neighbors to the south.

The Premier Cru vineyards of Cuis are primarily located around the northern part of the small forested area above the Côte des Blancs slope, with some vineyards just north of the village, partly on flatter ground and partly close to the small forested area between Cramant and Chouilly. Cuis wines tend to be lighter Blanc de Blancs, not in the least due to the more-or-less north-facing slopes. The level of acidity tends to be quite high, where the minerality comes to the fore even more than usual and explains why it is less common to find oaked Cuis-only Champagnes compared to oaked versions from Grand Cru villages.

Champagne Guy Larmandier

The late Guy Larmandier established his 22 acre estate in the heart of Vertus at the southern base of the Côte des Blancs; all the vineyard plots are distributed among the Grand Cru villages of Chouilly and Cramant and the Premier Cru villages of Vertus and Cuis.

Marie-Helene and François Larmandier

Following his death, the House has been managed by his wife, Colette, and their two children, François and Marie-Helene. With an annual production of 90,000 bottles, harvest is conducted manually and the wines are aged a minimum of 36 months on the lees, disgorged on order and receive a minimal dosage so as to emphasize the purity and finesse of the terroir.

Champagne Guy Larmandier, Côte-des-Blancs Premier Cru Vertus Brut Zéro ($51)

Champagne Guy Larmandier, Côte-des-Blancs Premier Cru Vertus Brut Zéro ($51)

90% Chardonnay and 10% Pinot Noir, aged for 3 years on the lees before disgorgement. The Premier Cru vineyard of Vertus is famous for its Pinot Noir, and it brings to the wine an earthy, red fruit richness. Disgorged July 2019.

Champagne Guy Larmandier, Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Cramant Blanc-de-Blancs Brut Zéro ($65)

Champagne Guy Larmandier, Côte-des-Blancs Grand Cru Cramant Blanc-de-Blancs Brut Zéro ($65)

From Larmandier’s 8-acre Grand Cru vineyard in Cramant, an epicenter of Chardonnay in Champagne. After the first fermentation, the wine was bottled and aged sur latte for five years before disgorgement; the nose offers fleshy fruit as well as subtle hints of calcareous minerality. Disgorged October 2021.

Champagne Guy Larmandier ‘Signé François – Vieilles Vignes ‘, 2010 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Crus Cramant & Chouilly Blanc-de-Blancs Brut Zéro ($99)

Champagne Guy Larmandier ‘Signé François – Vieilles Vignes ‘, 2010 Côte-des-Blancs Grand Crus Cramant & Chouilly Blanc-de-Blancs Brut Zéro ($99)

Larmandier’s prestige cuvée is produced from their oldest parcels of Chardonnay in the Grand Cru village of Cramant blended with a small amount of fruit from a holding in Chouilly. It spends five years on the lees before disgorgement. The wine’s chalky core shows itself in a clinging, almost salty finish. Disgorged January 2022.

Champagne Pierre Gimonnet

In Champagne, particularly in 2024, you can’t underestimate the value of legacy and old vines. Pierre Gimonnet began bottling estate Champagnes in 1935 with impressive Premier and Grand Cru terroirs from which to mine. In addition to the 33 acres in Cuis, he owned 27 acres of Chardonnay vines in the Grand Cru villages of Cramant and Chouilly, plus another two acres Oger and five in Premier Cru Vertus. Today, his grandson Didier has added Gimonnet also owns an acre or so of Pinot Noir, split between the Grand Cru of Aÿ and Premier Cru of Mareuil-sur-Aÿ.

Famille Pierre Gimonnet

In a region where there is a plethora of younger vines, these legacy vineyards are a key to the kingdom. Says Didier, “70% of our holdings are over 30 years old, of which some 40% are over 40 years old, with 100+ year old vines in the lieux-dits of Le Fond du Bateau, planted in 1911, and Buisson, planted in 1913, both in the Grand Cru village of Cramant.”

Underscoring this, he adds, “Our Spécial Club, for example, is based on Cramant Grand Cru, and includes pi 100+ year old vines in the lieux-dits of Le Fond du Bateau, and Buissons. The Cramant is very expressive and round; the Chouilly is similar in style but slightly less concentrated; Cuis is much more neutral, acid, fresh, aerial: This north-facing village is the coolest in the Côte des Blancs.”

Champagne Pierre Gimonnet, Premier Cru Cuis Blanc-de-Blancs Brut ($63)

Champagne Pierre Gimonnet, Premier Cru Cuis Blanc-de-Blancs Brut ($63)

From north-facing vineyards, 2017 fruit is enriched with 27% reserve wine from the 2010 to 2014 vintages. Élevage in stainless steel, sur latte for two years with disgorgement May 2018 and 6 grams/liter dosage. 130,000 bottles made.

Champagne Pierre Gimonnet ‘Gastronome’, 2015 Premier Cru Blanc-de-Blancs Brut ($72)

Champagne Pierre Gimonnet ‘Gastronome’, 2015 Premier Cru Blanc-de-Blancs Brut ($72)

As the name suggests, ‘Gastronome’ is designed to be food friendly by being produced under lower pressure, around 4.5 ‘atmospheres’ as opposed to Champagne’s usual 5-6. 51% Chouilly Grand Cru (Montaigu), 18% Cramant Grand Gru (Buissons), 5% Oger Grand Cru (Terres de Noël, Brulis and Champs Nérons), 25% Cuis Premier Cru (Roualles and Croix-Blanche) and 1% Vertus Premier cru. Disgorged in October 2019 with 5 grams/l liter dosage.

Champagne Pierre Gimonnet ‘Paradoxe’, 2013 Premier Cru Cuis Blanc-de-Blancs Brut ($75)

Champagne Pierre Gimonnet ‘Paradoxe’, 2013 Premier Cru Cuis Blanc-de-Blancs Brut ($75)

90% Pinot Noir from Aÿ Grand Cru and Mareuil-sur-Aÿ Premier Cru, 10% Chardonnay from Cuis Premier Cru with élevage in stainless steel; sur latte 71+ months with disgorgement April 2018. Dosed with 6 grams/liter.

Champagne Pierre Gimonnet ‘Oenophile’, 2012 Côte-des-Blancs Premier Cru Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($99)

Champagne Pierre Gimonnet ‘Oenophile’, 2012 Côte-des-Blancs Premier Cru Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($99)

79% Cramant Grand Cru from 7 lieux-dits, Chouilly Grand Cru (Montaigu and Ronds Buissons), Oger Grand Cru (Terres de Noël and Champs Nérons), 21% Cuis Premier Cru (Croix-Blanche and Roualles) and Versus Premier Cru. Fermented for eight months in stainless, bottled April 2013, disgorged in October 2019 after six years on lees.

Notebook …

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

To be Champagne is to be an aristocrat. Your origins may be humble and your feet may be in the dirt; your hands are scarred from pruning and your back aches from moving barrels. But your head is always in the stars.

As such, the struggle to preserve its identity has been at the heart of Champagne’s self-confidence. Although the Champagne controlled designation of origin (AOC) wasn’t recognized until 1936, defense of the designation by its producers goes back much further. Since the first bubble burst in the first glass of sparkling wine in Hautvillers Abbey, producers in Champagne have maintained that their terroirs are unique to the region and any other wine that bears the name is a pretender to their effervescent throne.

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

The lauded wine writer Peter Liem expands the number of sub-regions from four to seven, dividing the Vallée de la Marne into the Grand Vallée and the Vallée de la Marne; adding the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay and combining the disparate zones between the heart of Champagne and Côte de Bar into a single sub-zone.

Courtesy of Wine Scholar Guild

Lying beyond even Liem’s overview is a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that compliment or contrast when final cuvées are created.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Épernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

… Yet another reason why this tiny slice of northern France, a mere 132 square miles, remains both elite and precious.

- - -

Posted on 2024.05.13 in Crémant du Bourgogne, France, Champagne, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

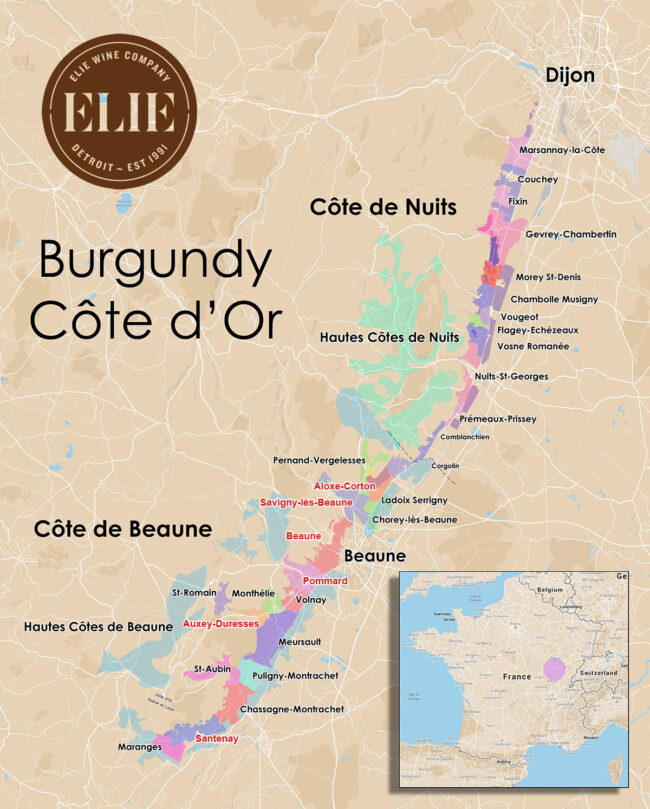

A Year In Burgundy II: Côte de Beaune’s Wines From The Incomparable 2015 Realize Their Potential, And Articulately Express The Distinctive Characters Of The Region’s Diverse Terroirs

In our last newsletter, we looked at Burgundy’s fantastic 2015 vintage as represented by some of the top vignerons in the Côte de Nuit. This week, we head south to Beaune to look at the stylistically-unique red wines of Nuit’s sister region. Beaune. You might expect that, being further south, the red wines of Beaune have a slightly better opportunity to ripen and become plush and rounded, and to some extent that is true: In general, Beaune’s climate is warmer than Nuit’s, and the rainfall is a little higher, allowing the grapes to better weather the late summer heat.

Whereas the top reds from the Côte de Nuits often have greater intensity and a firmer structure, top Côte de Beaune reds are frequently softer and lusher with soaring, earthy flavors laced with minerals and exotic spices. With age, they tend to cling to their fruit longer as tertiary flavors of coffee, hazelnut and forest bracken gradually take center stage.

Some of the domains presented here also have vineyards in Nuit, so if the names are familiar, it’s because these winemakers are border-hoppers whose wines are able to embody the best of the perfumed north and the silken fruit of the south.

2015 Burgundy: Hedonist’s Vintage

No one could better sum up Burgundy 2015 more splendidly than Jacques Devauges of Clos de Tart: “To make bad wine in 2015, one must wake up and say to yourself, ‘I will make bad wine.’”

This is not to say that it was an easy vintage—just a successful one. In fact—if the pun may be forgiven—the challenges ran hot and cold. Frost affected many Grand Cru vineyards early in the season and proved to be a harbinger of wet and cool temperatures in May. In mid-June, the weather became balmy, then hot, then seriously dry. According to Eric Remy at Domaine Leflaive, “Between June to August, we had 35 days when the temperature was above 30 degrees C and 15 days when the temperature was above 35 degrees C.”

The grapes were under hydric stress for most of that time; August brought off and on downpours, effectively saving the vintage, although the harvest window was narrow because potential alcohol levels were creeping up while acidity was dropping. White wine producers harvested end of August and nearly all the red wine producers harvested in the first week of September.

In all, there were many decisions a grower could have made in 2015 because there was so much material to work with. Some of the reds are elegant and ethereal—purposefully made so with light maceration and gentle handling. Others are dense, chewy and full-bodied, reminiscent of wine from warmer climates. Cécile Tremblay of the eponymous Vosne-Romanée domain says, “2015 had the best ripeness at harvest since I started winemaking. There was big quantity of polyphenols and too much of everything – I kept thinking of what to do with it. The big question was: Who am I making this wine for and what is the wine’s drinking window?”

In all, 2015—especially for red wines—has been heralded as having ‘nearly the concentration of 2005 allied with the sensuality of 2010.’

Ten Years After

That the finest Burgundies improve over time is no revelation. What is particularly interesting is that, unlike many age-worthy wines, Burgundy follows a somewhat unique path. There is no ‘peak’, for example—you make that discovery over the years as you sample a specific vintage from given label. There is a sort of ‘sine’ wave with multiple peaks and valleys. If a wine is unfriendly today, don’t assume it has passed its pinnacle—just push it further back in the cellar, and you’ll likely be rewarded.

For every rule in Burgundy, there are countless exceptions, but an experienced cellar master will tell you that after a few years in the bottle (generally between five and eight), when the fruit begins to fade a bit, there is a period when the wine may taste thin and a bit shrill. You might revive the old optimistic tombstone inscription: ‘Not dead, but sleeping.’

If the original wine was from a good vintage and was produced with circumspection, it will reanimate with tertiary notes—the fruit dries out to evoke raisin, fig or prune and more savory and musky aromas emerge as well, evocative of licorice, leather, mushroom, tobacco and dried bracken on a forest floor.

The wines in this collection have just entered this phase where the springtime purple notes have grown into the russet tones of autumn; along with us all, the refreshing, youthful smells of blackberry and cherry cola have matured into the introspective richness of adulthood.

Côte de Beaune

Here is a mnemonic device for remembering which shade of wine is best represented by the two subdivisions of the Côte d’Or, the Côte de Beaune and the Côte de Nuit: Bones are white, and the greatest of the Chardonnay-based white Burgundy (Corton-Charlemagne, Montrachet, et al) are from Beaune. Night is dark, and the greatest Pinot Noir-based reds (La Romanée-Conti, Chambertin, et al) come from the ‘Night Slopes’—the Côte de Nuit.

Of course, both regions make wines of either color. The Côte de Beaune is the southern half of the Côte d’Or escarpment, hilly country where, like the bowls of porridge in Goldilocks, the topsoils near the tops of the elevation are too sparse to support vines and, in the valleys, too fertile to produce top quality wine. The Goldilocks Zone (the mid-slopes) are where the Grand and Premier Cru vineyards are found, primarily at elevations between 720 and 980 feet. Drainage is good, and when vines are properly located to maximize sun exposure, the greatest Burgundies thrive and produce, year after year. The lesser, often forgettable Burgundies (generic Bourgogne) comes from the flatlands beneath the slopes; the fact that these wines are also made from Pinot Noir and Chardonnay is indication of why terroir matters. Likewise, the narrow band of regional appellation vineyards at the top of the slopes produce light wines labeled Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Beaune.

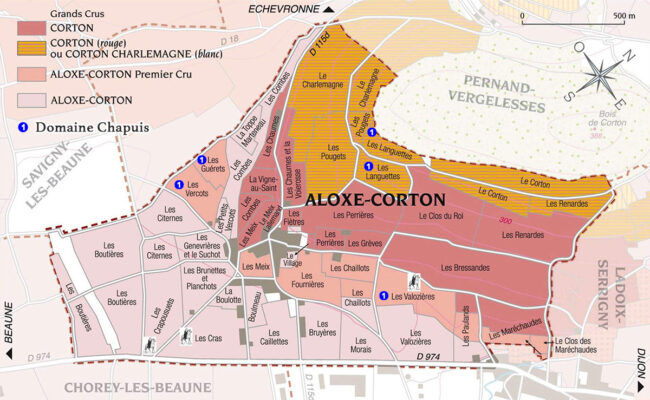

Aloxe-Corton

The appellation of Aloxe-Corton stands guard near vinous gates of the Grand Crus of Corton and Corton-Charlemagne, enjoying (if not the prestige) many similar growing conditions, producing almost exclusively red wines known for both a depth of color and an intensity of flavor. With vines facing east, the terroir is soil driven, with flint and limestone rich in potassium and phosphoric acid lending supple firmness to the wines, especially those from the appellation’s southern end.

Whereas white wines from the region exist, they are rare. The deep soils are better suited for Pinot Noir; the terroir is a geological cradle for this prima donna varietal. At altitudes averaging 800 feet, the vineyards are planted in reddish earth with flint and limestone debris known locally as ‘chaillots’ mixed in, likewise rich in potassium and phosphoric acid. Such soils favor supple, highly-bred wines, while clay and marl breeds firmness and complexity. Anticipate wild berry notes that intensify with age and evolve into peony and jasmine, brandied fruits, pistachio, prune and truffle.

Domaine Chapuis

Pierre and Claire Chapuis (assisted by their parents Maurice and Anne-Marie) manage almost 30 acres of vineyards, many on the steep slopes of the Corton hillside, where over a century of winemaking knowledge resides. Capitalizing on this heritage, the domain has enlarged and modernized the winery, investing in new equipment and replanting specific plots with more suitable vines. The couple practices lutte raisonnée in an effort to keep the winemaking process as natural as possible.

“Our soil work, fertilization, our phytosanitary strategies are designed to reduce our impact on the environment so that our vines grow within a preserved biodiversity,” says Pierre. “We vinify in the traditional way and all our wines are aged in French oak—12 months for the whites and up to 18 months for the reds. We prefer a low percentage of new barrels, about 10%, which allows us to express the full potential and finesse of our terroirs.”

Domaine Chapuis, 2015 Aloxe-Corton ($75)

Domaine Chapuis, 2015 Aloxe-Corton ($75)

Despite the majesty of the Corton moniker, Aloxe-Corton produces a unique style of wine, due in part to amphitheater in which they grow, found elsewhere in the Côte. On the Southern side of the appellation, the dark soils are made up of limestone debris while those on the Northern side, the soils are mainly pebbly. A blend of the two, like this one, may be reminiscent of a cross between Nuits-Saint-Georges and Beaune.

Domaine Chapuis, 2015 Aloxe-Corton Premier Cru ($96)

Domaine Chapuis, 2015 Aloxe-Corton Premier Cru ($96)

A blend of three plots where vines average 45 years old: Les Vercots, Les Guérets located in the southern part of the village and Les Valozières in the north, adjacent to the appellation Corton Les Bressandes.

Domaine Chapuis, 2015 Corton-Perrières Grand Cru ($180)

Domaine Chapuis, 2015 Corton-Perrières Grand Cru ($180)

Lying adjacent to Les Languettes at an average altitude of nearly a thousand feet, Corton Perrières is at the northern end of Beaune, where vines mingle with stone quarries and form a unique amphitheater. The wines are known for their finesse, rather than the typically austere Corton red which show as powerful, muscular and chewy.

Domaine Chapuis, 2015 Corton-Languettes Grand Cru ($180)

Domaine Chapuis, 2015 Corton-Languettes Grand Cru ($180)

Les Languettes is one of five Corton climats to produce both white and red wines, primarily because here, the soils vary noticeably across 18 acres—specifically in their proportions of limestone to iron-rich marlstone. The former suits Chardonnay (which makes up the majority of plantings); the latter Pinot Noir. The property is walled and divided by a vineyard track located on the upper slopes of the Corton hill. Facing south to south-southeast at just over one thousand feet in elevation, the vineyards are just below the famous tree-line.

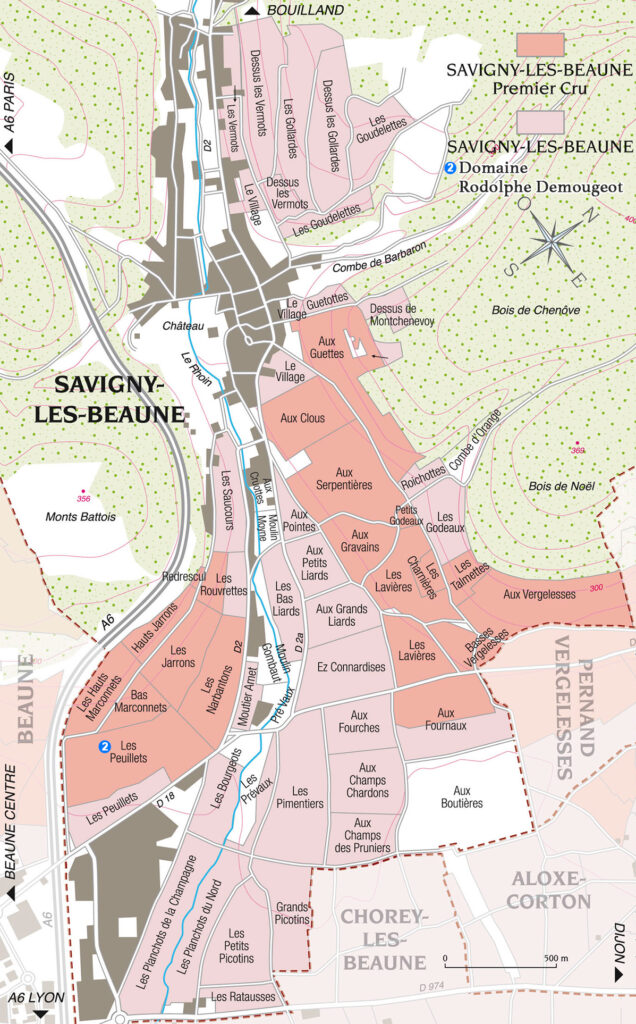

Savigny-lès-Beaune

Chances are, you love wines from the Rhine and are passionate about wines from the Rhône, but at first glance, ‘wines of the Rhoin’ may look like a typo. In fact, this small river flows from the cliffs of Bouilland through the commune of Savigny-lès-Beaune, and alluvia from the overflow adds fertility to the lower slopes of the hills of Beaune. With nearly nine hundred acres of vineyard, the appellation is one of Burgundy’s largest.

Savigny’s terroir features a gentle gradient that becomes steeper as the altitudes approach 1300 feet, where the geology is similar to that of the great Grand Cru hill of Corton. Favored exposures face the south, where the soils are gravelly and scattered with oolitic ironstone. Near the river valley, the red-brown limestone becomes more clay-rich pebble-filled while the east-facing slopes consist of sand and limestone.

Domaine Rodolphe Demougeot

When Rodolphe Demougeot created his estate in 1992, it was a tribute to his winegrower grandparents, in whose vineyards he worked as a boy and who gave him a taste for winegrowing. He began with nine acres in the Hautes-Côtes de Beaune, in Pommard and Beaune and has grown to twenty acres with plots acquired over the years in the municipalities of Savigny-les-Beaune, Monthelie and Meursault, where Rodolphe has been established since 1998.

But the move away from family tradition took some focus. He says, “I learned how to do ‘perfect’ chemical farming from them and had to deprogram both my vineyards and myself, which took a lot of time—something that evolved into a new sense of self and humility. I needed to learn to be a good farmer first, and then to improve performance in the cellar. I required an unflinching honesty about life and process.”

Domaine Rodolphe Demougeot, 2015 Savigny-lès-Beaune Premier Cru Les Peuillets ($95)

Domaine Rodolphe Demougeot, 2015 Savigny-lès-Beaune Premier Cru Les Peuillets ($95)

Upslope from the lieu-dit Les Bourgeots, Les Peuillets (planted in 1945) sits on a thin layer of high quality clay with limestone underneath, producing fragrant and pure wines with a delicacy that defies its concentration.

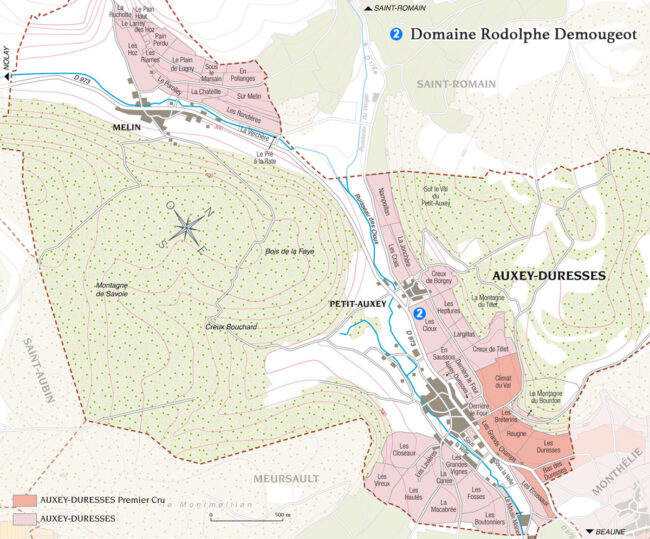

Auxey-Duresses

There was a time when the wines of Auxey-Duresses were sold under false premises—the reds were named Volnay and the whites, Meursault. In fact, experts could easily tell the difference. Yet, the differences have begun to evaporate as a new generation of winemaker in the appellation, coupled with a changing climate, has realized that Auxey-Duresses grapes may have the breeding to rival their hallowed neighbors without the need of fraud.

The first obstacle they had to overcome was geography. Unlike Meursault and Volnay, Auxey-Duresses vines cling to a variety of high slopes and have traditionally produced a hard red wine that is frequently sold to négociants for Bourgogne Rouge blends. But with patience, these same grapes, when bottled at estates within the appellation, improve immeasurably and become silken gems that may rival nearby powerhouses at a fraction of the cost.

Domaine Rodolphe Demougeot, 2015 Auxey-Duresses ‘Les Clous’ ($88)

Domaine Rodolphe Demougeot, 2015 Auxey-Duresses ‘Les Clous’ ($88)

Demougeot’s parcel of Les Clous is under an acre; it enjoys direct due-south exposure, ideal for this cooler appellation. The soils are limestone and clay, very well drained due to the ample mix of small and large stones deposited by the small creek that once flowed through this valley. 100% of the grapes are destemmed and fermented on native yeasts in cement and inox vats. Once pressed, it’s settled in a tank overnight and gravity fed into 85% old French barrels.

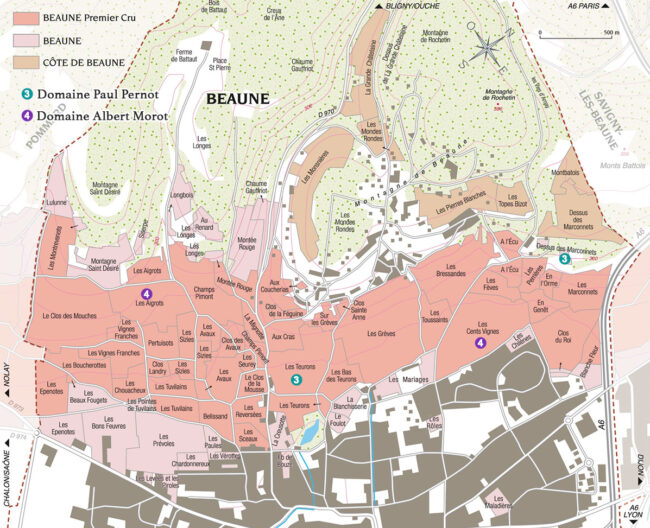

Beaune

The historical capital of Burgundy, Beaune eponymous appellation includes 42 Premier Cru Climats producing primarily red wine (887 acres of Pinot to Chardonnay’s 143). Village-level wines can be somewhat homogeneous, although from the northern end of the commune they tend to be intense while those from the southern end are smoother and fuller.

Beaune’s slopes are quite steep and the soil is thin; a breakdown of the terroir is a mouthful and a half: On the lower slopes are Argovian marls and deep soils, white, grey or yellow, tinged with red from the iron in the Oxfordian limestone. Exposures are easterly to due-south at altitudes between 700 feet and a thousand feet.

Domaine Paul Pernot

When Paul Pernot founded his domain in 1959, he centered on 25 acres of vines planted on 200-year-old family land in Puligny-Montrachet. An artisan winemaker, he developed his vineyards with great respect for the soil.

Among the top growers in Puligny, Pernod wines are celebrated for their delicacy and poise while remaining rich, ripe and with the structure to age. The property sells over 60% of its production to négociants, saving only the cream of the crop for its own bottlings. The vineyards and cellar are now managed by Paul’s two sons, Michel and Paul Jr, together with Paul Jr’s son, Philippe, and Michel’s daughter Alvina (who also as her own project). Michel heads up work in the winery, while Paul Jr and Philippe manage the vineyards while Alvina manages the administrative side. They maintain a traditional approach to winemaking with very little having changed at the domaine in the last four decades.

Domaine Paul Pernot, 2015 Beaune ‘Clos du Dessus des Marconnets’ Monopole ($96)

Domaine Paul Pernot, 2015 Beaune ‘Clos du Dessus des Marconnets’ Monopole ($96)

The name of this east-facing, entirely-walled vineyard refers to a German tribe called the Marcomans who once settled near the nine-acre plot. The Chardonnays are situated at the top of the hill where it is windy, and grow in a marl and sandy soil, while the Pinot Noirs are situated mid-slope where they are exposed to more sun. As in most such Burgundian expositions, soil erosion at the top of the plot produces stonier terroirs as it grows more alluvial toward the bottom. The monopole (owned entirely by the family) was planted by Paul between 1957 and 1961 and pre-dates modern clones.

Domaine Paul Pernot, 2015 Beaune Premier Cru Clos des Teurons ($110)

Domaine Paul Pernot, 2015 Beaune Premier Cru Clos des Teurons ($110)

Sun-drenched des Teurons is one of the more highly acclaimed climats in Beaune; it sits high on the slope facing east, and its limestone-rich terroir produces grapes that ripen early and wines that age beautifully.

Domaine Albert Morot

Established by Albert Morot in 1820, Domaine Albert Morot is considered one of the leading properties in the Côte de Beaune. The estate consists of about 20 acres of vineyards, almost entirely in the Beaune Premiers Crus of Les Teurons, Les Gréves, Les Toussaints, Les Bressandes, Les Cent Vignes, Les Marconnets, and La Bataillére.

Geoffrey Choppin de Janvry has been responsible for the wines since 2000, when his aunt Françoise Choppin (great-granddaughter of Albert Morot) retired. While retaining the deep focus on quality started by his aunt in the 1980s, including green harvesting, double sorting during harvesting, and minimizing cellar interventions, Geoffroy has ushered the estate into a new era by gradually implementing organic farming methods.

Domaine Albert Morot, 2015 Beaune Premier Cru Cent-Vignes ($110)

Domaine Albert Morot, 2015 Beaune Premier Cru Cent-Vignes ($110)

The three acre plot of “Les Cent Vignes” (one hundred vines) is located at the bottom of the slope with a southeastern exposure and is composed mainly of loam and clay soils. The vines on this plot were planted in 1958 and are known for producing wines that are remarkable for their color and delicacy of aromas. On the palate the wines combine complexity and mellowness.

Domaine Albert Morot, 2015 Beaune Premier Cru Aigrots Rouge ($110)

Domaine Albert Morot, 2015 Beaune Premier Cru Aigrots Rouge ($110)

Located next to the celebrated Clos des Mouches vineyard on the middle of the slope, Les Aigrots faces east. The stony soil of this two acre plot is rich in loam and clay, producing full-bodied, generous wines. The vines are between 29 and 37 years old.

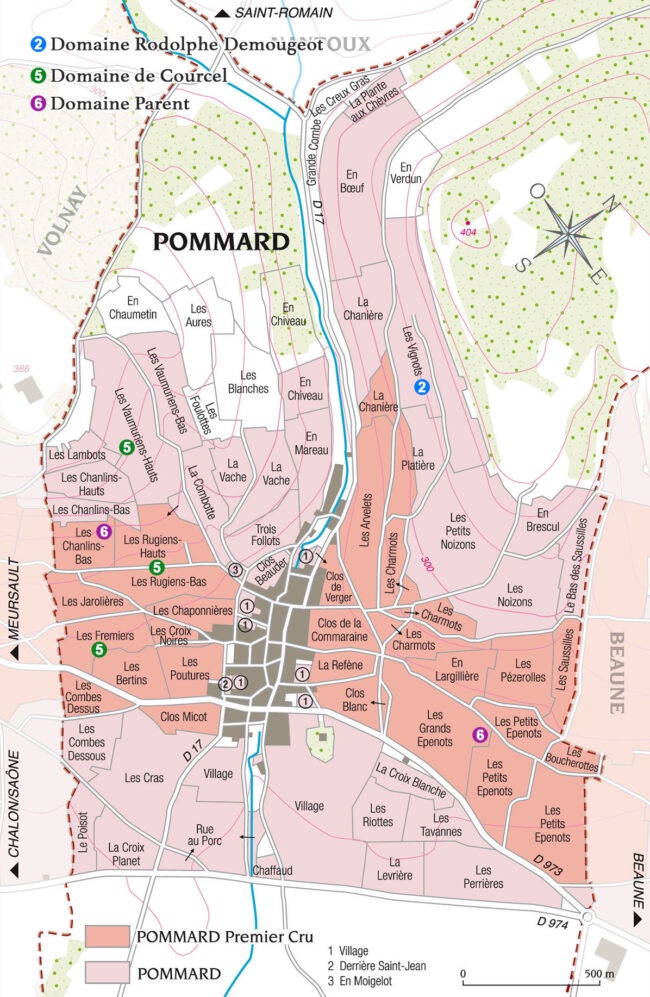

Pommard

If Burgundy is a volume of poetry, Pommard might be considered its Alfred, Lord Tennyson, offering power and rich structure, a charge of the Light Brigade, only with a substantially safer outcome. Pommard is the beginning of serious Pinot Noir in Burgundy; nothing else is grown and nothing else allowed besides (perhaps inexplicably) a few vineyards of the Lemberger/ Sankt-Laurent cross ‘André.’ Aptly named for Pomona, the Roman god of fruit trees, Pommard’s most muscular wines hail from its mid-slope Premier Cru vineyards which run in a nearly uninterrupted from the commune boundaries of Beaune in the north to Volnay in the south. Even that may belie the quality of these wines; most experts believe that the Les Épenots and Les Rugiens Premier Crus should be promoted to join Corton in its Grand Cru status. Once in line for this prestigious upgrade, the vignerons of the time were wary of the restrictive Grand Cru production laws and declined the offer.

Domaine Rodolphe Demougeot, 2015 Pommard Les Vignots ($120)

Domaine Rodolphe Demougeot, 2015 Pommard Les Vignots ($120)

Les Vignots is a lieu-dit situated on the upper slope of the combe behind the village of Pommard; it faces south, giving the wines typical Pommard power while its elevation (over a thousand feet) lends high-toned aromas and finesse—especially, a racy mineral edge. The average vine age (fifty years) also lends to the wine’s remarkable concentration.

Domaine de Courcel

“Too often winemakers make a style, not a wine,” says Gilles de Courcel, “which is what many négociants do when they blend wines they buy from different estates.”

For the past four hundred years, the de Courcel family has produced award-winning Pommards from some of the region’s most renowned vineyards. Its reputation is all the more remarkable, considering that the domain never produces more than 30,000 bottles per year.

Essentially built around Premier Cru sites, de Courcel’s 26 acres are peppered across Le Grand Clos des Épenots, Les Rugiens, Les Frémiers and Les Croix Noires. Le Grand Clos des Épenots, which accounts for 50% of the Domaine’s production, and Les Rugiens are in a climat class of their own. The estate is currently managed by Gilles de Courcel, Anne Bommelaer and Marie de Courcel.

Domaine de Courcel, 2015 Pommard ‘Les Vaumuriens’ ($130)

Domaine de Courcel, 2015 Pommard ‘Les Vaumuriens’ ($130)

Vaumuriens is a Village-level appellation located just above Rugiens where soils are white with limestone and fairly thin; with vines around 40 years old, the four-acre vineyard produces spicy wines with aromas leaning towards cassis, but with a slight tropical edge.

Domaine de Courcel, 2015 Pommard Premier Cru Les Fremiers ($190)

Domaine de Courcel, 2015 Pommard Premier Cru Les Fremiers ($190)

Frémiers is a two-acre climat located south of Pommard, right below Rugiens, at the base of the slope. The red and brown topsoil is rich in both clay and limestone and is deeper than that of the Rugiens; the resulting wines are elegant and sophisticated with fine-grained tannins and pie-spice aromatics.

Domaine de Courcel, 2015 Pommard Premier Cru Les Rugiens ($320)

Domaine de Courcel, 2015 Pommard Premier Cru Les Rugiens ($320)

Les Rugiens consists of two parcels, Les Rugiens Haut and Les Rugiens Bas, based on their respectively higher and lower positions near the summit of the Pommard slope. The name comes from the French word ‘rouge’ and refers to the reddish soil in the vineyard, a result of high iron content. As such, these wines tend to be among the most rugged in Pommard and are generally best if cellared for a minimum of ten years.

Domaine Parent

A lawyer by training, meticulous winemaker Anne Parent is the matriarch of Pommard. Passionate not only about her wines but about the role of female vignerons in Burgundy, she founded the Women’s Winemaker Association in Burgundy and was its first president. Along with her sister, Catherine, she took over the Parent estate in 1998, becoming the 12th generation of winemakers in the family.

Parent is one of the great names in Pommard. The 25+ acre domaine boasts some of the finest parcels in the appellation, as well as holdings in Corton, Beaune, Ladoix, and Monthélie. Recent vintages have seen the domaine firing on all cylinders as they have moved towards an organic (certified 2013) and biodynamic approach to viticulture. Anne believes that these techniques help the soil regain its energy, and subsequently produce the most balanced fruit possible. Her aim is to make, “wines with character and personality, but also subtle, complex and sensual,” while maintaining the health of the environment and the people that work the vines.

Anne Parent calls 2015, “A very yum-yum vintage!”

Domaine Parent, 2015 Pommard Premier Cru Les Chanlins ($150)

Domaine Parent, 2015 Pommard Premier Cru Les Chanlins ($150)

Les Chanlins is an 80-year-old climat with an ideal location abutting Volnay Premier Cru Les Pitures and Pommard Premier Cru Les Rugiens Haut. Here, limestone-heavy soils combine Pommard’s power with Volnay’s trademark elegance to make Pinot Noir with a sublime combination of grace and intensity. Parent’s is vinified with 5% whole clusters and was matured in 50% new oak.

Domaine Parent, 2015 Pommard Premier Cru Les Epenots ($180)

Domaine Parent, 2015 Pommard Premier Cru Les Epenots ($180)

Pommard has no Grand Crus; Épenots—which may be worthy of the status—is one of two parcels under the name Les Épenots (Grand and Petit) situated in the north of the commune on 62 acres of clay and calcareous soil. The word Épenots comes from the French épine, referring to the spiny bushes that once surrounded the vineyard. Parent’s wine is a blend of Grands and Petits Épenots, with half whole bunch and half new wood.

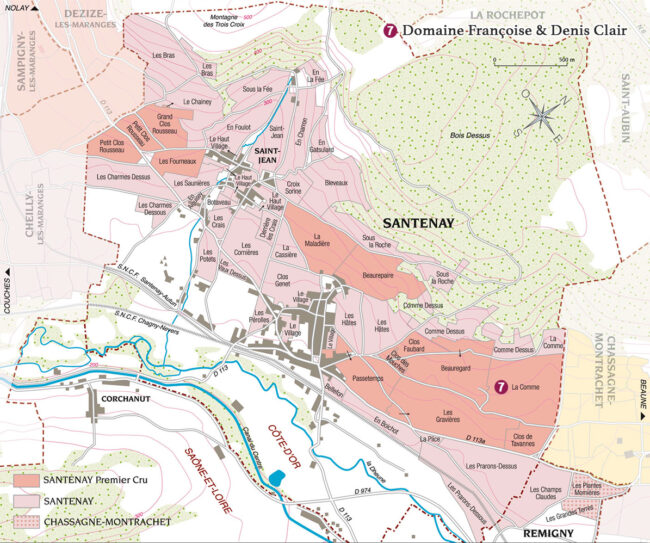

Santenay

Jean-Marc Vincent, president of the Santenay producers association, maintains that the appellation has gotten an undeserved bad rap. It’s a stereotype, he believes, that might be rooted in the fact that Santenay has no Grand Cru vineyards: “And yet, so far in the 21st century, Santenay has produced more than 50 wines rated 90 points or higher in ‘Wine Spectator‘ blind tastings, with retail prices from $30 to well below three figures for our top Crus.”

Santenay soils contain less limestone than many of its northerly neighbors, and more marlstone, although proportions vary based on where the vineyard is located—grey limestone can be found up to a height of 1700 feet, while at a thousand feet, oolitic limestone lies over a layer of marl. The ideal exposure for these vineyards is east to southeast.

Although the wines are often referred to as ‘rustic’ rather than ‘elegant’, this is not to say that the wines of Santenay do not capture the poetry of Pinot Noir; Santenay has the soul of Volnay and the body of Pommard. To those who love such earthy, complex Burgundies, Santenay is a marvelously affordable discovery.

Domaine Françoise & Denis Clair

Domaine Françoise & Denis Clair was created in 1986 when Denis set out to bottle his own wine – The Clair family had owned parcels in the Santenay area for generations but sold most of their production to négociants. Initially stretching over only 12 acres of Pinot Noir, today the domaine has expanded to 37 acres, mainly with the acquisition of Chardonnay plots from the best terroirs in Saint-Aubin, where Françoise was born and where the winery is located.

Denis built the domaine’s reputation through seductive red wines. Their son, Jean-Baptiste Clair, joined the family business in 2000 and quickly elevated the production of white wines to the highest levels of quality. The domaine takes great effort to work as organically as possible. The fruit is hand-picked and the wines are fermented by indigenous yeasts. Sulfite addition is minimal. Like most winemakers at the highest level, the aim is to produce wines that speak of the land from which they arise.

Domaine Françoise & Denis Clair, 2015 Santenay Premier Cru Clos de la Comme ($79)

Domaine Françoise & Denis Clair, 2015 Santenay Premier Cru Clos de la Comme ($79)

The best vineyards of Santenay come from the northern end of the appellation, where they border those of Chassagne-Montrachet. Here, the increased proportion of gravel, marl and limestone in the soil adds structure and richness to the grapes, which in turn produce a more powerful wine. Premier Cru ‘La Comme’ faces southeast, allowing grapes that reach full maturity even in cooler vintages and powerhouse reds in warmer ones. The name is the regional form of Combe, because the vineyard is in the extension of the Combe of Saint-Aubin.

Notebook …

Making Sense Of Burgundy: What Makes It So Singular

Above all, terroir is an ideology; a flight of vinous fancy that insists a wine’s taste and aroma reflect its place of origin. This reflection may be subtle or overt, but there’s plenty of science behind it. Terroir includes specific soil types, topography, microclimate, landscape characteristics and biodiversity—all features that interact with a winemaker’s choice of viticultural and enological techniques.

Nowhere is this more in evidence than Burgundy, where the notion of place-identity is sacrosanct. The central role that terroir plays in every hierarchal level is not only part of the culture, but it is based on centuries’ worth of confirmation. Although in loose geological terms the entire appellation sits on an ancient limestone seabed, this unity is shattered into an immense mosaic of thousands of individual ‘climats’ from which the vine draws color and flavor. Some are ludicrously tiny—renowned Romanée, for example, is under five acres—and the secret alchemy of terroir may be diversified throughout a village, a vineyard, and even in vine rows within that vineyard.

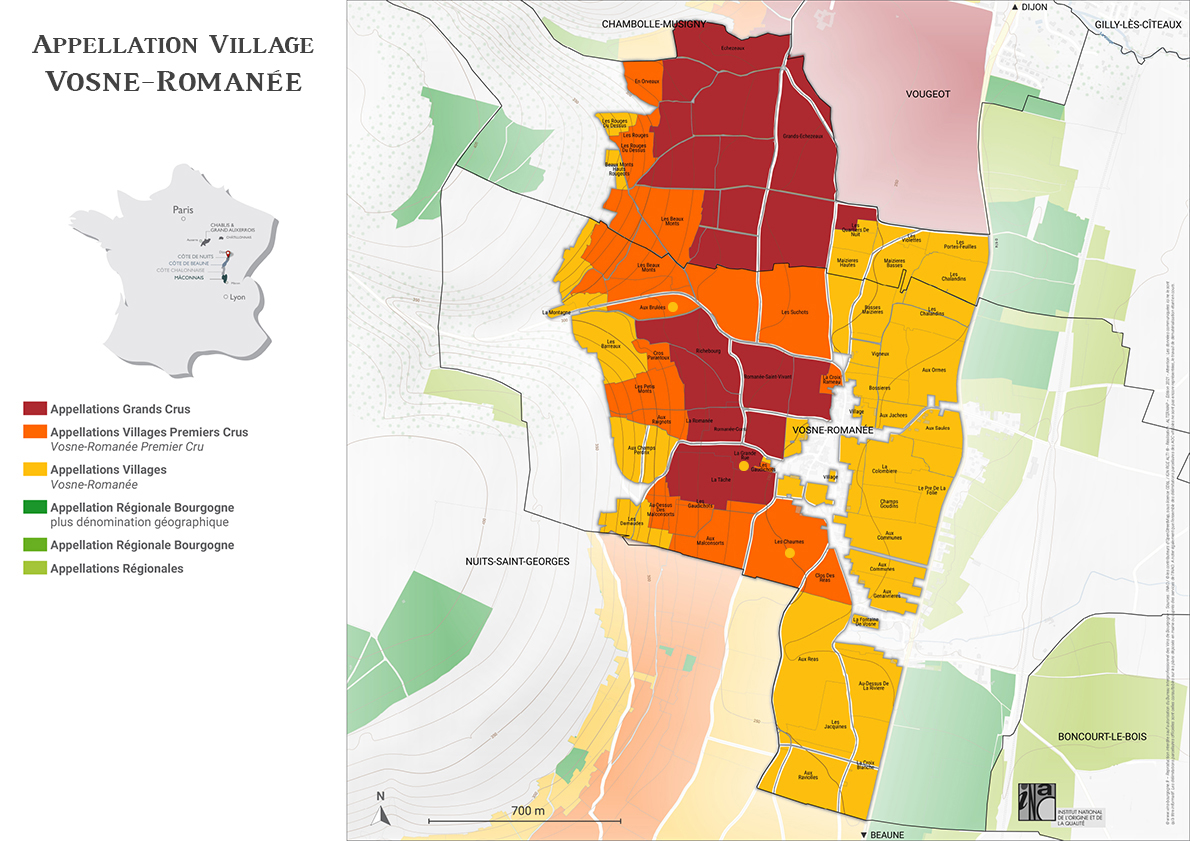

Burgundian labels reflect that; the quality-focused grades with which we have become so familiar—Bourgogne, Village, Premier Cru and Grand Cru—each have individual sets of rules regarding yield, grapes and production methods that winemakers are legally required to follow. From there, we may or may not find the name of a climat, a term used interchangeably with lieu-dit. Although the Grand Cru wines are generally considered to be classified on the vineyard-plot level and defined as separate AOPs (with the exception of Chablis Grand Cru), some Grand Crus are in fact divided into several lieux-dits. Echézeaux, for example, includes 10, one of which has two alternative names: Les Cruots is also known as Vignes Blanches. Although it is illegal to use the name of lieux-dits on Grand Cru labels, the law is flouted in Clos de Vougeot and one or two other Grand Crus to consumer-friendly ends.

The Value Of Burgundy, Regardless Of The Price

Burgundy ‘the concept’ has always hovered in the empyrean—even if the best of the physical stuff drifted out of most rational price ranges. More than stately, austere Bordeaux, more than hedonistic Rhône, more than transcendent Champagne, more than ethereal Loire, Burgundy represents beauty and power recombinant; the Athena of wine.

Its value in the perception outstrips its value on the palate; whereas wine prices are set on reputation of terroirs, the poetry of our mental landscapes remains beyond our ability to quantify. It can only be considered by sense, not cents.

In the retail business, we’re charged with vigilance to ensure that the prices we charge is balanced by the products we sell and few places present more of a challenge than Burgundy, the most coveted wine on the planet. The changing climate may have brought more fine Burgundy appellations to market, but there are fewer of the wines themselves—yields are often a trade-off when vineyards are increasingly dry and hot throughout the season and erratic weather produces more and more crop-devastating storms. Prices have risen so sharply that sticker-shock is an inevitable part of Burgundy shopping and the shelf-dressing domains have priced themselves virtually beyond reach.

Still, although the concept of value may be on a sliding scale in Burgundy, relative bargains abound. And in any case, we can ascend straight up the hierarchy, from village wines to Premier Crus to the highly-rarefied domains of the Grand Cru, nothing will ever quite approach the finesse that Burgundy plays on the imagination.

- - -

Posted on 2024.05.01 in Côte de Beaune, Pommard, Beaune, Côte de Beaune, Savigny-lès-Beaune, Aloxe-Corton, Auxey-Duresses, Santenay, France, Burgundy, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

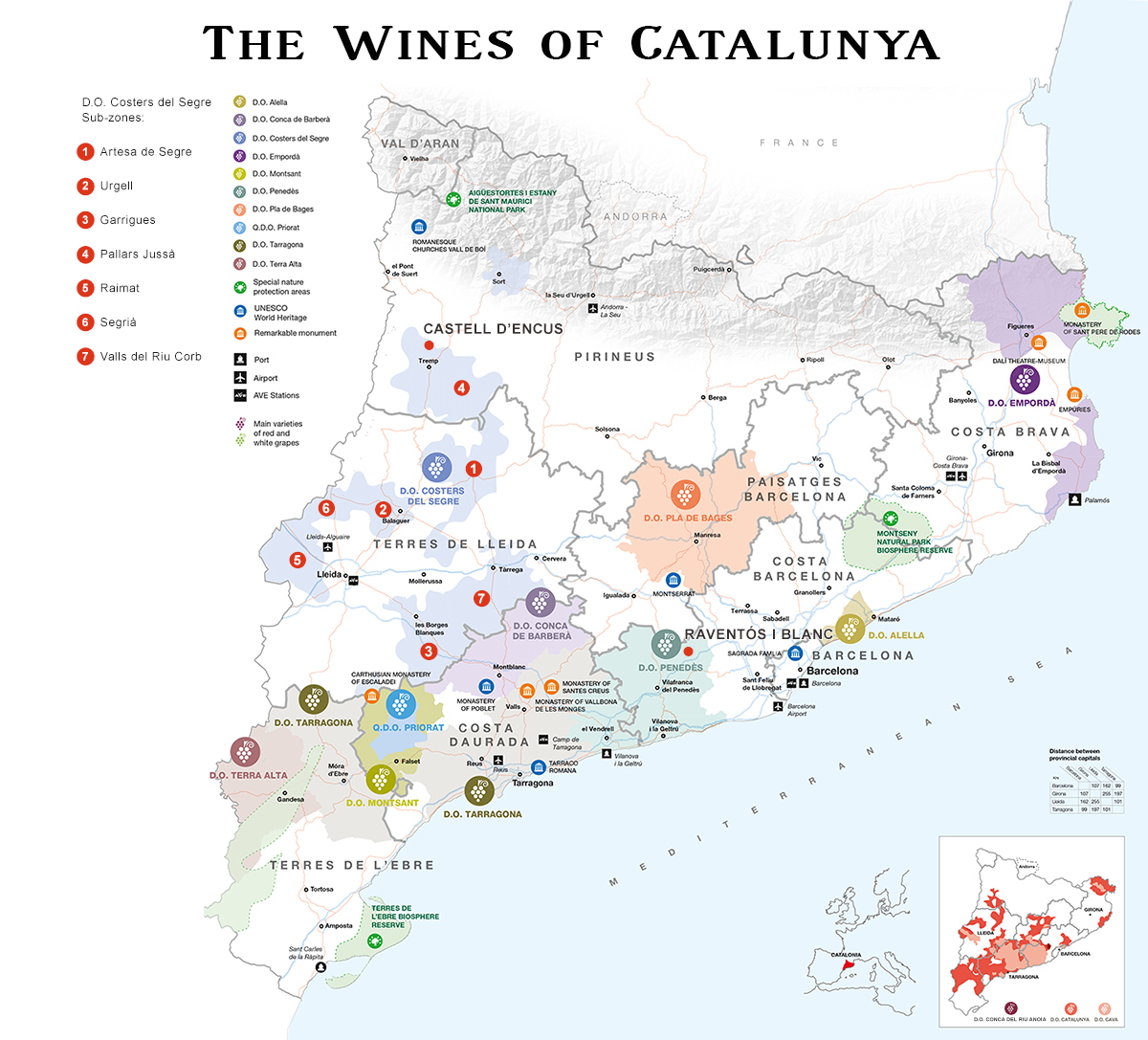

Redefining Spanish Wines: Catalunya’s Deeply Rooted, Daringly Innovative Wine Culture In The New Age Four Neo-vignerons (9-Bottle Red, White & Rosé Pack For $285)

All Things Catalunyan: Join Us for Saturday Sips To Usher In “La Diada de Sant Jordi’

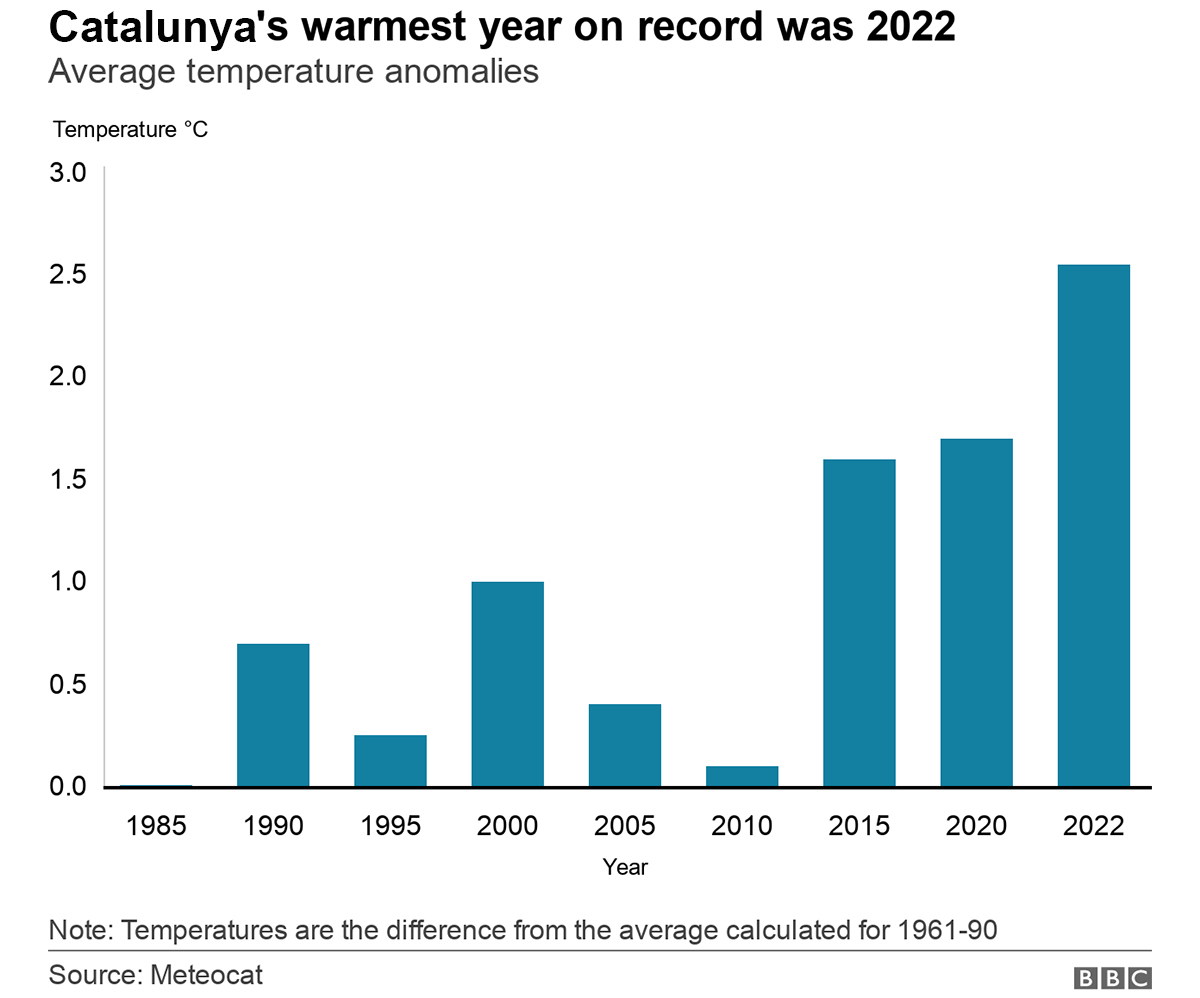

‘La Diada de Sant Jordi’ falls on April 23 in the Catalan holiday calendar, a day of books and roses, and it is a great reason to resume our all-day, in-store Saturday Sips. Among the themes we will be exploring in weeks to come is ‘vinecology’—the agricultural and techno-fixes that will alter the world of wine as profoundly as global climate change is altering traditional (and non-traditional) wine growing areas.

(Climate) Change Is Afoot In Catalunya

With apologies to Professor Higgins, the rain in Spain is not only dodging the plains, it’s playing havoc up and down the entire Mediterranean coast, extending from Spain to North Africa and Sicily as well. Last year, this persistent drought ranked among the ten most costly climate disasters in the world, and in real time, Catalunya is undergoing the worst drought in a century, with water reserves at 16% of capacity. Hotels are filling swimming pools with seawater and those whose livelihoods are tied to agriculture are wondering what the intensity of this summer will bring; last year, fruit growers threw out entire crops in order to use their diminishing water supplies to save their trees. Even traditionally dry-farmed industries like olive production and wine growing are crippled by these severe heat waves, and farmers who irrigate have it even worse, since by law, they are the first ones to relinquish water rights.

Adaptation to the climate crisis is happening throughout Catalunya; there is no other choice. But to date, much of it improvised and tends to take place only when the worst has already happened. Like the old Inuit following the caribou, modern winemakers are being forced to follow the thermometer, and this has led to an exploration of vineyard space in regions that were once too cold to produce reliable harvests.

The Vigneron’s Dilemma

It’s no secret that grape vines have been known to produce the best wines where the challenges are greatest. Vines placed under natural stress, struggling to find water and nutrients, tend to produce fruit that is more vibrant in flavor and balanced in acid with smoother tannins. Sites that are flat, well-irrigated and sunny have long been considered ‘no-brainer terroirs’ that over-produce and under-perform.

When challenged by drought, producers of this industrial-style wine reach into pockets deeper than the aquifers, and they will survive. The small winegrower, faced with mounting losses and plummeting harvests, are like the vines themselves: Sooner or later, they simply wither away.

And it is not just dryness. In Penedès, 2020 brought two times the rain of a normal year, which was followed by three years of drought. The unpredictable nature of climate change takes an emotional toll on the winemakers as well as a financial one. The dilemma they face is often less about a desire to change and more about the clock: It is well-established that vineyards stationed at higher altitudes are able to retain more water and produce higher-quality grapes, and that some varieties are more drought-resistant than others. But starting over in new regions takes time, and as climatic conditions worse, sadly, time is a resource that many wineries simply do not have.

Counter Or Adapt

With equal apologies to Jim Morrison and The Doors: Girl, when your vineyards becomes as hot as a funeral pyre, take it higher. The most delicious irony in changing weather patterns may be that regions once considered too cold for vines are warming to the point that they can produce quality wines. In Catalunya, vineyards at the foothills of the Pyrenees are being planted at altitudes up to 4,000 feet. “Twenty-five years ago, it would have been impossible,” says Miguel Torres Maczassek of Familia Torres. “At higher elevations, peak temperatures are not necessarily much cooler, but intense heat lasts for shorter periods and nighttime temperatures are colder than at lower altitudes. This increased diurnal shift (the temperature swing over the course of a day) helps grapes to ripen at a more even pace, over a longer period of time, than where temperatures remain relatively stable.”

But pushing altitudes also creates challenges: Soils, particularly on slopes, are generally poorer, water is scarcer and unexpected weather events like frosts and hailstorms are always a threat. Whereas this may ultimately result in better wine overall, the challenges for winemakers are prodigious. In the northeast of Spain, including coastal vineyards, the response has been two-fold: Adapt current vineyards to the ‘new normal’ by replanting to more heat-tolerant varietals, or eke out space at higher elevations to take advantage of the plus-side of a global negative.

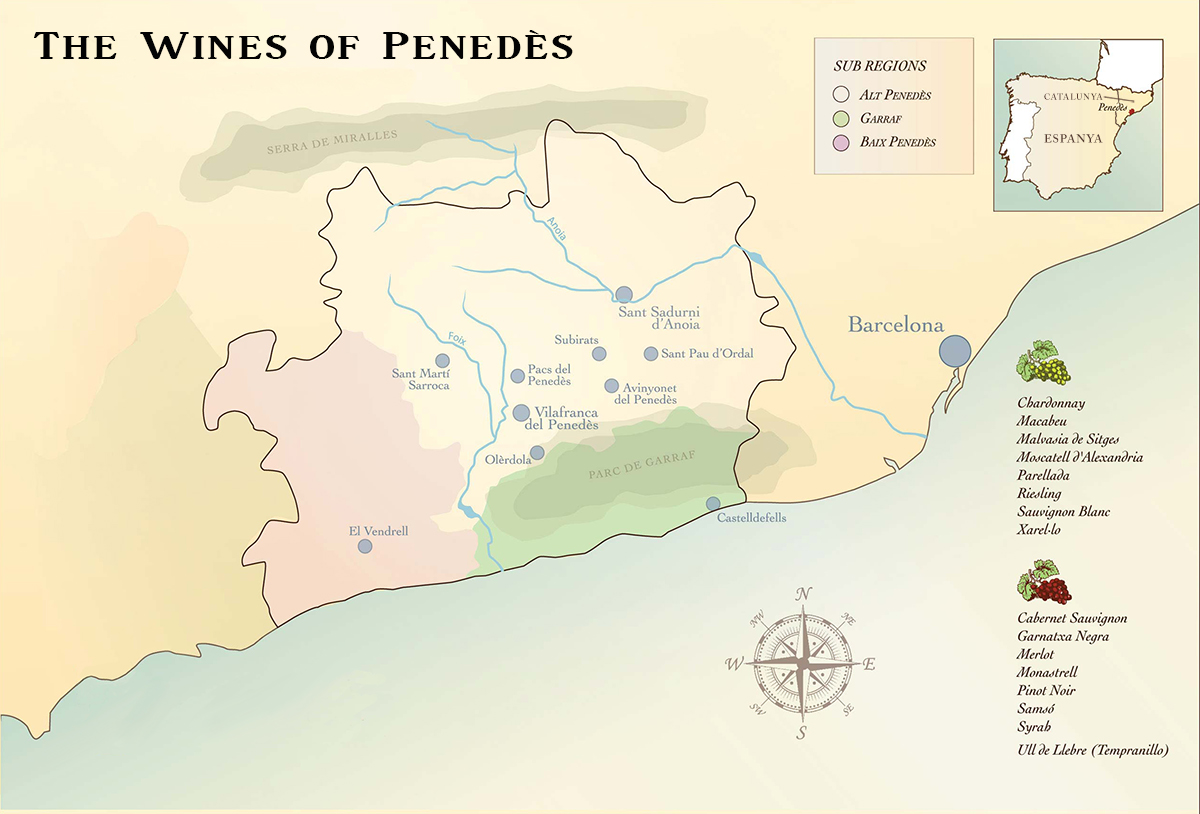

Penedès

Uphill, Wealth Of Indigenous Grape Riches

About an hour south of Barcelona, nestled splendidly between the mountains and the sea, Penedès is most active growing region in Catalunya. The region contains some of the oldest wine-growing appellations in Europe, and produces consistently and reliably thanks to a multitude of terroirs. The region is best known for Cava, Spain’s answer to Méthode Champenoise sparkling wine, generally produced from the trinity of indigenous grapes, Macabeu, Parellada and Xarel·lo, occasionally fattened-up with Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Garnatxa and Monastrell. All are permitted in various concentrations for Cava blends.

Roughly divided into three subzones, the mountainous Alt-Penedès produces the highest quality wine, followed by Baix Penedès in the low-lying coastal areas and Penedès Central, responsible for most of the region’s bulk production.

Although the area has been making wine since the days of the Phoenicians, Penedès’ modern era began in 1960 when its DO designation was granted, and—largely through the efforts of Miguel Torres—the region as a whole began to upgrade production methods, including temperature-controlled fermentation in stainless steel tanks and experimentation with non-indigenous grape varieties such as Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. Since then, although quality has skyrocketed among all the wines of Penedès, the region remains known primarily for its sparkling wines, making the highly regarded, oak-aged reds and crisp, vibrant whites (especially those made with the Cava standby Xarel·lo) part of a remarkable journey of discovery.

VallDolina

The name ‘VallDolina’ is a description of the landscape surrounding Can Tutusaus, an estate which has stood amid these pine groves since 1348. ‘Dolinas’ are depressions formed in areas rich in limestone soils while ‘vall’ is Catalan for valley. In 1987, seduced by this mysterious land, Joan Badell bottled his first wines and planted his first trained vines. In 1999, his son Raimon, who was then studying oenology, became a close collaborator and opted to turn the estate toward ecological and biodynamic agriculture.

“Bottling the land,” is the way that Raimon Badell describes his interpretation of winemaking. “We only work with grapes picked from this estate,” he says, “where vines are situated between 800 and 1500 feet above sea level, bordering the Natural Park of the Massís del Garraf. The vineyards grow on hills with calcareous-clay soil and produce where the climate is distinctly Mediterranean, strongly influenced by the vicinity of the sea.”

Raimon Badell

As a team, Raimon and his wife Anna have replanted the ancient terraces set in a property otherwise dominated by pine trees interspersed with glimpses of the Mediterranean Sea. The oldest vines at Tutusaus were planted during a last-century’s craze for international grape varieties, and the Merlot remains an outstanding Spanish example of this variety.

Anna adds, “VallDolina identifies with the territory with the aim that our wines offer a sensitive expression of the landscape, with the idea of determining the different tasks following the lunar calendar as our grandparents did and at the same time using agricultural concepts the most environmentally friendly.”

1 VallDolina, 2020 Cava Reserva Brut-Nature ($19) Sparkling

1 VallDolina, 2020 Cava Reserva Brut-Nature ($19) Sparkling

The three traditional Cava varieties, 38% Xarel·lo, 32% Macabeu, 22% Parellada with 8% splash of Chardonnay sourced from estate-owned, organically certified vineyards with red clay and limestone soils. Vinified and fermented in stainless steel tanks, with secondary fermentation inside the bottle and 24 months on lees before disgorgement.

Alemany i Corrio

There are matches made in Heaven and those made in vineyards; credit the latter to the life partnership of Irene Alemany and Laurent Corrio, whose small-batch, low-intervention wines are proving that the Alt-Penedès is among the most exciting places to be making wine today. Great wine is a technical beast, but without the intensity of passion, it loses much of its savor: “Our wine is as soft as a gentle kiss, but one where you end by biting your partner’s lip,” says Irene.

Irene Alemany

The couple met at the University of Burgundy in Dijon, then apprenticed together in vineyards in France and California. But their future was written in chalk and loam following a visit to Irene’s parents in Lavern in the Penedès; that was when Irene’s father suggested that they consider using the family vines to start their own operation. This treasure trove encompassed several varieties of grapes between 25 and 60 years old. They leapt at the opportunity—their first harvest was in 1999 and their first bottling in 2002. From the beginning, they followed their French training, remaking the classics in their own way, keeping the process as natural as possible while seeking to reflect the expression of the varieties and the character of the terroir to the maximum extent.

In the process, they are credited with producing the first ‘garage’ wines of New Penedès. Their ‘Vi de Garatge’ series may be thought of as ‘tailor-made’ wines relying on precision in both field and cellar.

“What we want to accomplish,” says Irene, “is that when people taste our wines there is something in the soul of the wine that talks to them and will make them remember.”

2 Alemany i Corrió ‘Principia Mathematica’, 2022 Vi de Garatge ‘Penedès’ ($30) White

2 Alemany i Corrió ‘Principia Mathematica’, 2022 Vi de Garatge ‘Penedès’ ($30) White

100% Xarel·lo – Originating with low-yields from a seven-acre plot where the vines are over fifty years old, Principia Mathematica was fermented in French oak (10% new) and aged for ten months in foudres/stainless steel. The wine shows a Meursault-esque intensity beneath crisp white stone fruit, notably apricot, defined by a light toasted-almond undertow. 665 cases produced.

3 Alemany i Corrió ‘Cargol Treu Vi’, 2021 Vi de Garatge ‘Penedès’ ($31) White

3 Alemany i Corrió ‘Cargol Treu Vi’, 2021 Vi de Garatge ‘Penedès’ ($31) White

Another pure Xarel·lo beauty; Cargol Treu Vi comes from 75 year old vines planted on chalky soil, then vinified on wild yeast in 300 liter French oak barrels, 25% new. The wine shows spring flowers, stone fruit and lemon zest behind hints of smoke with a long, salt-tinged finish. 175 cases produced.

Can Sumoi

Into a rarified atmosphere of Catalunyan pride and passion and secessionist spirit, Pepe Raventós has embellished the canvas with his own unique set of colors. Born to the vine and enamored of the bosky hills and sprawling vineyards of Catalan wine country, Raventós spent his childhood picking grapes at Sant Sadurní d’Anoia. Sant Sadurní is, of course, the home of more than eighty Cava producers and wine is cornerstone of the local economy. It’s also where 21 generations of Pepe Raventós’ family have lived, dating back to the 15th century.

Pepe Raventós

At two thousand feet above sea level (in the Serra de l’Home range) Can Sumoi is the highest estate in the Penedès; Mallorca and the Ebro Delta are visible from the rooftop of the winery’s 350-year-old farmhouse. Below, 50 acres of vineyards sprawl across limestone-rich soil between stands of oak and white pine, which to the ecology-driven Raventós, share equal importance with the vines. “Forests,” he says, “protect the biodiversity of the estate; they are the green lungs of the world.”

The wines of Can Sumoi are also green insofar as they are produced using Certified Organic methods; vineyards are tended with natural compost, free of pesticides and with minimal intervention; a herd of sheep and goats is allowed to graze semi-freely among the vines. Certain esoteric biodynamic techniques may sound strange to laymen (such as timing vineyard activity to the phases of the moon) but to Raventós, they make perfect sense: “When the moon is ascendant, plant fluids concentrate more towards the roots of plants, and that’s when you want to do the pruning—so you don’t damage the plant.”

4 Can Sumoi ‘Montònega’, 2021 Espumoso ‘Ancestral’ Brut-Nature ($27) Sparkling

4 Can Sumoi ‘Montònega’, 2021 Espumoso ‘Ancestral’ Brut-Nature ($27) Sparkling

Montònega is a pink-berried clone of Parellada capable of producing excellent monovarietal sparkling wines, particularly when cultivated in the high-altitude Pla de Manlleu of Penedès. The wine is Pet-Nat, meaning that it is made via the traditional method without additives, stabilization or filtration. The wine is dry and savory with delicate aromas of apple skin and citrus.

5 Can Sumoi ‘Garnatxa Blanca’, 2022 ‘Penedès’ ($28) White

5 Can Sumoi ‘Garnatxa Blanca’, 2022 ‘Penedès’ ($28) White

This golden-hued mutation of the dark-skinned Garnatxa Negra originated in northern Spain. Can Sumoi’s is drawn from vineyards in the Serra del Montmell, nearly two thousand feet above sea level where the soils are stony and limestone-based. The wine shows apricot and lychee as well as green fruits like honeydew and pear, but the herbal quality is a defining feature.

6 Can Sumoi ‘La Rosa’, 2022 Penedès ($26) Rosé

6 Can Sumoi ‘La Rosa’, 2022 Penedès ($26) Rosé

An aromatic rosé made from high-altitude Xarel·lo and Sumoll, destemmed, lightly crushed and briefly macerated, with fermentation carried out in stainless steel tanks on indigenous yeasts. A distinct and elegant expression of Mediterranean character with wild strawberry and citrus notes behind a springtime floral bouquet.

7 Can Sumoi ‘Garnatxa – Sumoll’, 2021 ‘Penedès’ ($28) Red

7 Can Sumoi ‘Garnatxa – Sumoll’, 2021 ‘Penedès’ ($28) Red

Mountain grapes from the highest estate in the Penedès, showing boysenberry, cinnamon and pomegranate while combining rusticity with an essential elegance that is, like salinity, a Can Sumoi trademark.

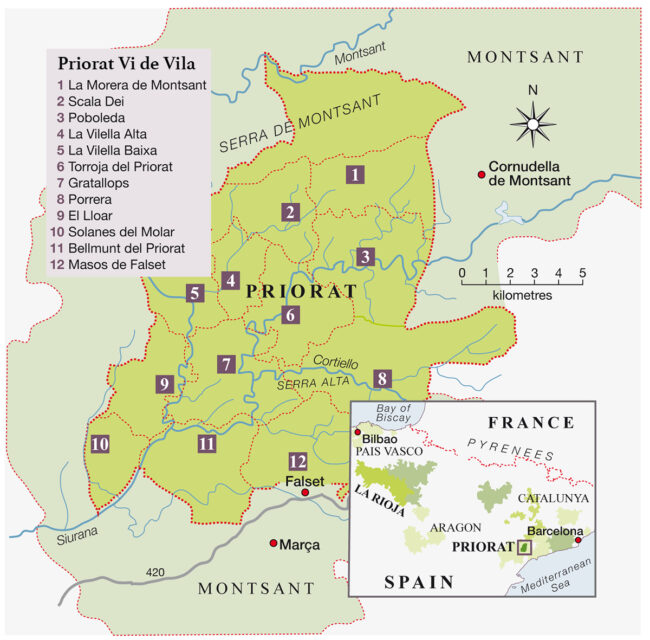

Priorat

Goliath Into David

In the ever-popular Godzilla trope, the beast periodically rises from slumber and emerges from unforgiving depths to make his presence … well, obvious.

For most of the 20th century, sleepy Priorat remained below the same sort of radar, with vineyards struggling up steep slate hills southwest of Barcelona, content (for the time being) to leave production to cooperatives, who largely made cheap, indifferent wine.

Priorat’s first rage from the obscure into the noteworthy came in the late twentieth century, when young winemakers recognized the potential of the unique Priorat soils—stuff that the Catalans call ‘llicorella’. They found this stony brown slate, occasionally sparkling with quartzite, filled with old-vine Garnatxa and Carinyena that was capable of producing muscular wines of largesse and longevity, and the first wave of truly presentable Priorat wines hit the wine world like a tsunami.

Around 2010, winemakers began to question this style; as tastes changed, such oak-heavy blockbusters lacked the most vital element toward which wine fashion was leaning: Freshness and finesse. In yet another rediscovery of identity and potential, Priorat winemakers began to change their techniques, employing Burgundian methods in part to find floral tones and mineral undercurrents in the classic indigenous grapes, and transforming the gargantuan to the graceful; Goliath, perhaps, into David, or Godzilla into the sleek and streamlined dragons of Greek mythology.

Along with this evolution, the concept of terroir has come to the forefront, with DOQ Priorat exploring a new category, Vi de Vila, in which wine from 12 areas may add the name of the local village to their labels, bringing a sense of identity into an appellation that spent most of its history being somewhat unidentifiable.

Ona

A native Spaniard, born, raised and educated in Barcelona, Núria Garrote i Esteve has dedicated many years to pursuing wine from an elite Franco-Iberian group of trailblazers. Through her partnership with several extraordinarily innovative Catalunyan winemakers, she has assembled a few special collaborative cuvées named after her daughter, Ona. The original labels were written in Ona’s own five-year-old hand, and each wine has a story to tell.

“There are as many points of view articulated through wine and cultivation techniques as there are good wines,” Núria says. “My producers are as different from each other as their farms.”

Masos de Falset hillside composed of ‘Llicorella’ consisting of reddish-black slate with small particles of mica quartz, different layers of soil filled in by clayey soil. Clos Petitona winemaker Blai Ferré i Just, right

Among Núria’s Ona-producing partners is Blai Ferré, their first collaboration was in 2013. Blai fell in love with winemaking while a teenager working the fields with one of Priorat’s leading producers, Alvaro Palacios. He then purchased a handful of acres, much of it former vineyard land that had been abandoned, and set to work planting drought-adapted rootstocks and adopting a style of under-extraction to better nurture these wines so that the dazzling minerality of Priorat’s smoky schist can shine through.

8 Ona, 2020 Priorat ($22) Red

8 Ona, 2020 Priorat ($22) Red

A blend of 40% Garnatxa, 40% Syrah and 20% Carinyena 20% grown on Blai Ferré’s 12 acres; the wine is aged in stainless steel and shows ripe cherry and plum misted in smokiness, spice with wet-stone minerality on the finish. About 5000 bottles produced.

9 Clos Petitona, 2018 Priorat – Masos de Falset ($74) Red

9 Clos Petitona, 2018 Priorat – Masos de Falset ($74) Red

Clos Petitona (Little Ona) is produced from a single plot located in the village of Falset, and is typical of the extreme slopes of the region, terraced against the ravages of time. It was planted in 1949 with equal parts Garnatxa Negra and Garnatxa Peluda vines, with a south-east orientation and a surface area just under four acres. Due to the age of the vines, yields are extremely low, giving the wines superb concentration and structure.