What Land Really Smells Like: Two Passionate Grower-Makers Capture New Catalunya’s Mediterranean Fauna & Flora, Natural·ly (6-Bottle Pack $175)

‘Streaks of independence, evolving practices, a respect for nature and for those who coddle it.’ … It’s hard to find better examples of these traits than in the wilds of New Catalunya, where a younger generation has delved deeply into the remarkable earth of sea-and-sun-kissed Penedès.

Among the best, natural winemakers Pepe Raventós and Francesc Escala and the husband/wife team Raimon Badell and Anna have rewritten some of the oldest rules while emblazoning new ones, becoming templates for a wine-making renaissance that has wowed us at Elie’s for many years. These two iconic, iconoclastic wine houses have managed to bottle personality, honesty and knowledge, as this week’s 6-Bottle Pack ($175) should make obvious.

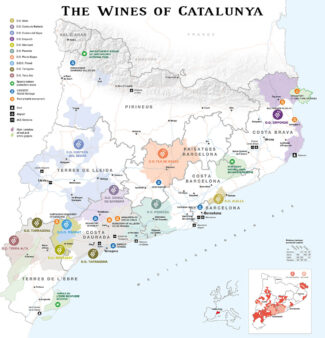

The New Catalunya

To a wine novice, France may seem to be a bottomless morass of rules and regulations, appellations and multi-syllabic, hyphenated names.

Spain suffers from the opposite misinterpretation: It is often oversimplified.

When the conversation turns to Spanish wine, many people are lost after the word Rioja is mentioned. They may have a surface familiarity with Cava based primarily on price, but may not be aware that Freixenet (the top-selling brand) is even Spanish.

The truth is, heavy, overly-oaked Riojas and inexpensive Cava have long been efficiently sellable standards that animated the American market, and even Spanish consumers may not be familiar with the spectacular array of styles and varieties that make their nation every bit the equal of the world’s other wine producing countries.

Not only that, but Spain produces more wine than any other country after Italy.

The Spanish wine renaissance of recent decades may be playing out best in Catalunya—the ‘land of castles’—a fascinating autonomous community in the northeast corner of the Iberian Peninsula. For many years, like much of Europe, young people moved away from an agricultural life in pursuit of cosmopolitan prospects.

Recently, however, the flight has reversed course and young people intent on creating artisan wines are finding new opportunities in an ancient culture. They are moving away from the trend-driven varieties that gained a foothold during the 1990s (Merlot, Cabernet and Syrah) and many are focused on an array of local grapes like Xarel·lo, Macabeu, Garnatxa Blanca and Parellada along with indigenous reds like Garnatxa, Monastrell and Trepat. Styles are also moving away from heavy wood-soaked Rioja and toward freshness, acidity and finer structure. And a growing number of smaller Spanish producers have rejected industrial farming in favor of organic and biodynamic practices in hopes of a sustainable future where this time, their own children may decide to stick around.

Returning to Roots: Indigenous Grapes

Ironically, most Americans are very familiar with French grape varieties even though they rarely appear on French wine labels. California is largely responsible for this phenomenon, an appellation that in its youth was less sold on terroir and more on identifying and exploiting popular flavors. That has changed, of course, but variety almost always figures prominently on California labels, even those that also tout a given patch of land.

Following this trend as a means of increasing market share, Spain tore out many thousands of acres of indigenous grapes in favor of flavor-of-the-month. Graced by an ideal climate under which many these varieties thrived, a move back to the roots (literally) of winemaking has prompted the revival of those grapes that grew in Spain initially. To a neophyte, these names may look like the typist had his finger on the wrong row of keys, but each of them—Tinta del Pais, Ull de Llebre, Cencibel, Pedro Ximénez et al.—have their own unique profile and create wines unparalleled elsewhere in the world.

Reaching Back into The Past: Méthode Ancestrale

Méthode Ancestrale is worthy of its name; it is the oldest known method of producing sparkling wine. It is also known as ‘rurale, gaillacoise, artisanale, pétillant naturel’ and in some appellations, ‘pétillant originel’, but in brief, it is a technique that involves bottling wine partway through its primary fermentation to trap carbon dioxide gas in the bottle, creating a gentle, bubbly carbonation.

It is similar to, but not identical to the Méthode Champenoise used in Champagne and, by law, for Cava. Ancestral method wines go through a single fermentation and are bottled before the fermentation process is completed, producing a wine with low alcohol gentle carbonation, and muted sweetness; they are generally unfiltered. Champenoise method wines go through a second fermentation in the bottle, which raises its alcohol content and creates its signature bubbles.

The Gesture of Natural: Wine in The Raw

In wine, ‘natural’ is a concept before it’s a style. It refers to a philosophy; an attitude. It may involve a regimen of rituals or it may be as simple as a gesture, but the goal, in nearly every case, is the purest expression of terroir that a winemaker, working within a given vineyard, can fashion. Not all natural wines are created equal, and some are clearly better than others, but of course, neither is every estate the same, nor every soil type, nor each individual vigneron’s ideology.

The theory is sound: To reveal the most honest nuances in a grape’s nature, especially when reared in a specific environment, the less intervention used, the better. If flaws arise in the final product—off-flavors, rogue, or ‘stuck’ fermentation (when natures takes its course), it may often be laid at the door of inexperience. Natural wine purists often claim that this technique is ancient and that making without preservatives is the historical precedent. That’s not entirely true, of course; using sulfites to kill bacteria or errant yeast strains dates to the 8th century BCE. What is fact, however, is that some ‘natural’ wines are wonderful and others are not, and that the most successful arise from an overall organoleptic perspective may be better called ‘low-intervention’ wine, or ‘raw’ wine—terminology now adopted by many vignerons and sommeliers.

At its most dogmatic and (arguably) most OCD, natural wines come from vineyards not sprayed with pesticides or herbicides, where the grapes are picked by hand and fermented with native years; they are fined via gravity and use no additives to preserve or shore up flavor, including sugar and sulfites. Winemakers who prefer to eliminate the very real risk of contaminating an entire harvest may use small amounts of sulfites to preserve and stabilize (10 to 35 parts per million) and in natural wine circles, this is generally considered an acceptable amount, especially if the estate maintains a biodynamic approach to vineyard management.

Can Sumoi

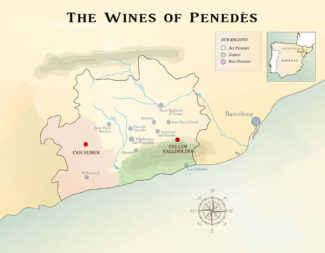

Meet Pepe Raventós and Francesc Escala: A pair of childhood buddies who are living the dream—their own dream, of course, in the backwoods of Catalunya. Having found Can Sumoi (an agricultural farm dating to 1645) in the mountains of the Baix Penedès where they realized their vision and dreams in the remarkable landscape and passion for natural wines.

They purchased the property from an ailing farmer, Josep Mateu, whom they have allowed to live on in the farmhouse where he was born. Having grown up in a culture where hard work was a condition of survival, Mateu is able to appreciate the vigor of the young men to whom the torch has been passed.

Pepe Raventós, Can Sumoi, and Josep Mateu

The estate sprawls across a thousand acres, of which fewer than fifty are vineyards, planted to Parellada, Xarel-lo and Sumoll. Reaching elevations of nearly two thousand feet, orientation of the vines depends on variety; Parellada, for example, prefers eastern and western exposures. The sea, which can be seen in the east, has left its influence, and the terroir is filled with marine fossils that are over a million years old. So clear is the atmosphere at this elevation that, on days without wind, you can see Mallorca and the Ebro Delta.

Almost 800 acres of the farm is woodland, and as Josep Mateu looks back at his life, he says, “Now that the forest has been gaining ground from the vineyard, between the trunks of the holm oaks you can see the white pines and tall oak trees, the old dry stone walls we built many years ago to facilitate the cultivation of the vines in terraces.”

This return to nature is the cornerstone of Pepe Raventós’ approach to vine cultivation and the natural wines of Raventós i Blanc. He says, “I’m not a great specialist in biodynamics, but I observe the countryside and I see how it responds. If we apply its methodology and in a few years I see that the earth is more alive, more balanced and we are getting better wines, I continue to apply it …of course.”

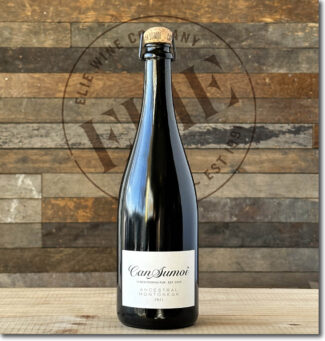

Can Sumoi ‘Ancestral Montònega’, 2021 Catalunya Escumòs Mètode Ancestral Brut Nature ‘Natural’ ($27) (sparkling)

Can Sumoi ‘Ancestral Montònega’, 2021 Catalunya Escumòs Mètode Ancestral Brut Nature ‘Natural’ ($27) (sparkling)

‘Montònega’ is a local name for Parellada, and this sparkling wine is made entirely from this native variety. Hand harvested, destemmed and softly pressed in the winery, the fermentation process begins in stainless steel tanks and finishes in the bottle. Only indigenous yeast is employed; the must spends 14 days inert and 16 days in the bottle; no sugar is added and the wine is neither stabilized nor filtered. Natural SO2 is 13mg/l Aged in bottle for 4 months before release and shows crisp, focused minerality with citrus, apple and herbal notes, especially rosemary.

Can Sumoi ‘Xarel·lo’, 2020 Penedès ‘Natural’ ($27) (white)

Can Sumoi ‘Xarel·lo’, 2020 Penedès ‘Natural’ ($27) (white)

A striking still-wine example of this unusual variety, generally used in sparkling wine, from vineyards located at 1800 feet on clay-calcareous soils. After the manual harvest, the grapes are destemmed and gently pressed in an inert atmosphere. Fermentation is carried out in stainless steel on yeasts native to the vineyard. Once the alcoholic fermentation has ended, the wine goes through the malolactic fermentation spontaneously, then rests on lees for 3 months, with bâtonnage twice a week. It is bottled without stabilizing or filtering and shows Xarel·lo’s characteristic peach, crisp green apple and toasted almond notes.

Can Sumoi ‘Sumoll Garnatxa’, 2021 Penedès ‘Natural’ ($27) (red)

Can Sumoi ‘Sumoll Garnatxa’, 2021 Penedès ‘Natural’ ($27) (red)

Grenache by any other name would smell as sweet, and when blended with Sumoll, it offers an intense nose of wild fruits and Mediterranean forest herbs. Made from an equal combination of Sumoll and Grenache, Can Sumoi’s ‘Sumoll Garnatxa’ first sorts grapes harvested from biodynamic vineyards filled with rocky, clay and limestone soils sitting at 2000 feet elevation, one of Penedès’ highest points. The grapes were harvested during September, destemmed and hand (or rather, foot) pressed in an inert atmosphere, then spontaneously fermented in stainless steel tanks for 15 days, then kept in the tanks for a full year, after which it was bottled and aged for a further 6 months without added sulfites before hitting the market. It is light and elegant with the crisp acidity inherent in mountain wines.

Uvala (Celler VallDolina)

Based at Can Tutusaus, in the center of the remote village of Olesa de Bonesvalls in the Garraf Natural Park, VallDolina has become a pet project of husband Raimon Badell and wife Anna, whose award-winning Cava is proudly featured on the shelves here at Elie’s. As a team, Raimon and Anna have replanted ancient terraces in a rocky landscape otherwise dominated by pine trees interspersed with glimpses of the Mediterranean sea. The oldest vines at VallDolina were planted by Raimon’s father during a last-century’s craze for international grape varieties, and the Merlot remains an outstanding Spanish example of this variety.

The estate and its surrounding pine groves has stood since 1348, but it was only in 1729 that the country house was rebuilt within the village of Olesa, where the cellar is presently situated. The property comprises several acres of olive groves—resuscitated after years of neglect—and about thirty acres of vines. The rest is a maze of pine and oak forests, dwarf shrubs, brooms, fennel, rosemary, thyme, lavender and dwarf palms.

In 1987, seduced by this mysterious land, Joan Badell bottled his first wines and planted his first trained vines. In 1999, his son Raimon, who was then studying oenology, became a close collaborator and opted to turn the estate toward ecological and biodynamical agriculture. In 2006, oenologist Ferran Gil García joined the VallDolina Viticulturists and Winemakers of Can Tutusaus project, and began tending the vineyards. Their joint efforts has made possible the production of a white wine, a rosé, three outstanding reds and three different types of Cava.

Raimon Badell, Celler VallDolina

“We only work with grapes picked from this estate,” says Rai, “where vines are situated between 800 and 1500 feet above sea level, bordering the Natural Park of the Massif of Garraf. The vineyards grow on hills with calcareous-clay soil and produce where the climate is distinctly Mediterranean, strongly influenced by the vicinity of the sea.”

Celler VallDolina ‘Uvala Ancestral – Xarel·lo’, 2021 Catalunya Escumòs Mètode Ancestral ‘Natural’ ($25) (sparkling)

Celler VallDolina ‘Uvala Ancestral – Xarel·lo’, 2021 Catalunya Escumòs Mètode Ancestral ‘Natural’ ($25) (sparkling)

Gold in a bottle; from the pale yellow hue with gilded tones to the wealth of aromas that evolve and expand with golden tones. The creamy nuances behind the purity of white fruit is the result of native yeasts while the unctuous mouth and salty undertones are the product of the terroir.

Celler VallDolina ‘Uvala Brisat – Xarel·lo’, 2021 Catalunya ‘Natural’ ($35) (orange)

Celler VallDolina ‘Uvala Brisat – Xarel·lo’, 2021 Catalunya ‘Natural’ ($35) (orange)

‘Brisa’ is a Catalan word meaning ‘pomace’ and ‘Brisat’ refers to the prolonged skin contact this wine underwent through the fermentation process. The wine shows straw yellow with pink highlights; the aroma is gorgeous, filled with citrus, peach, flowers and herbs that follow through the delicate fruity mouth and a pleasant tannins in a long finish.

Celler VallDolina ‘Uvalal – Marselan’, 2019 Catalunya ‘Natural’ ($34) (red)

Celler VallDolina ‘Uvalal – Marselan’, 2019 Catalunya ‘Natural’ ($34) (red)

Marselan is a red wine grape that is a cross between Cabernet Sauvignon and Grenache, first bred in 1961 by Paul Truel near the French town of Marseillan. The first Spanish Marselan grapes were planted in 1990 and have made a little headway in Catalunya. VallDolina’s version is softly kissed with aromas of bramble fruits (raspberry and blackberry), cassis and ripe cherry accompanied by spicy notes of cinnamon and clove.

- - -

Posted on 2023.03.28 in Spain DO, Penedes, Wine-Aid Packages

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Aligote, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Cinsault, Clairette, Corvina, Counoise, Dolcetto, Erbamat, Ferrol, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Gamay, Garnacha, Garnacha Tintorera, Gewurztraminer, Graciano, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malbec, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marcelan, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montònega, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscat, Natural, Niellucciu, Parellada, Patrimonio, Pedro Ximénez, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Pouilly Fuisse, Pouilly Loche, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Riesling, Rondinella, Rose, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sagrantino, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Sciacarellu, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Search