A Sense of Where You Are: The Burgundification of Catalunya’s Priorat in Three Villages by a Trio of Talented and Ambitious Producers

Priorat has been making serious wine since Roman ‘vinitors’ started carving terraces into the Spanish landscape, but its history as a DOQ (DOC) is much shorter. To be precise, Priorat only received this status in 2000. The advantage to being able to write your own rules in the 21st century is that you have a lot of templates to choose from, and for Priorat—a rugged and remote region southwest of Barcelona—the pyramid scheme of Burgundy has proven ideal.

Winemakers, some without a family tradition or ancestral lands (‘Generation Zero,’ as they refer to themselves) have taken to heart the idea that if Priorat wines are to find a place of quality on the world’s stage, the region’s unique slate-laden soils and severe elevations have to form the heart of their identity.

This week, we’ll feature a trio of talented and ambitious producers who are carrying forward a torch that they lit themselves—ambassadors from a dynamic region whose evolution we can watch in real time.

Priorat Wine: A Rebirth

‘Prior’ Priorat: A region that often took style cues from Rioja, whose heavily-oaked, Tempranillo-based wines are so oaked that its traditional classification system based on oak aging times. But Priorat, being David to Rioja’s Goliath (Priorat has fewer than five thousand acres planted to vines—Rioja has 162,000) cannot begin to compete in terms of output. For many years, Priorat struggled to find a marketable identity, and its isolation and terrains merely added to the issues; one producer describes a prolonged impoverishment that lasted until the 1990s.

It was around this time that a new generation of winemakers began to revive old vineyards, rediscover family plots or—recognizing the potential for a quality revolution—come from elsewhere to settle in and earn a reputation. Says José Mas of Costers del Priorat: “Some people work in wine because they have family vineyards. I don’t have any inherited obligation to work here; Priorat is just my passion.”

The diversity of the landscape makes ‘recipe’ wines impossible. Largely built around Garnatxa, with Carinyena, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah and Merlot taking up supporting roles, the high elevation and reddish-black slate produce wines with a remarkable freshness that is light years removed from the oaked dinosaurs of the not-so-distant past. According to Valentí Llagostera of Mas Doix, “These are wake-up wines, not sofa wines.”

Since quantity eludes it, in order to capitalize on the strengths of Priorat as a mecca for quality, a new system of classification was called for. Álvaro Palacios took the lead, and as a member of the Board of Directors of the Regulatory Council, he spearheaded a drive to establish a tiered system based on the Burgundian model, the single most ambitious reclassification system in the recent history.

The Burgundification of Priorat

‘Els Noms de la Terra’, or ‘The Names of the Land,’ is a remarkable transplant. Based on Burgundy’s pyramid of quality rules, Priorat became (in 2007) the first Spanish region to introduce ‘village’ level wines while categorizing based on the quality of the vineyard and the age of the vines. Each category has stringent requirements of vineyard ownership, varietal percentages, maximum yields, age of vines and their traceability. The Consejo Regulador has created the following categories:

- DOQ Priorat; regional wine, grapes sourced from anywhere in the appellation

- DOQ Priorat Vi de Vila

- DOQ Priorat Vi de Paratge; single-vineyard wine

- DOQ Priorat Vinya Classificada

- DOQ Gran Vinya Classificada

- Velles Vinyes: 75 years old vines, or those planted before 1945, can be used in all categories

As in Burgundy, the base of the pyramid is regional wines that can be produced with grapes grown anywhere in the appellation; they are labelled DOQ (DOC) Priorat. Since the groundbreaking 2007 vintage, Vi de Vila (village wine) is restricted to 12 villages approved by the Consejo. 2017 saw the introduction of the Vi de Paratge (459 named sites similar to Burgundian climats or lieux-dits) and single-vineyard wines which will be labelled either as Vinya Classificada (similar to Premier Cru) or Gran Vinya Classificada (the equivalent of a Grand Cru).

Nothing will explain or demystify the glory that is Priorat wine, but such a system has done wonders for our understanding of it; there is nothing quite like classification to break down a complicated region into bite-sized chunks—or, in this case, sips.

Família Nin-Ortiz

Priorat Vi de Vila ‘Porrera’

Porrera, linked to the valley of the river Cortiella, may have fewer than 500 residents, but it boasts 25 working wineries. Its sun-kissed vineyards are sheltered from the north winds by the Molló mountains and the rugged terrain, which also produces PDO Siurana olive oil.

Sharing a commitment to old vineyard plots and biodynamic techniques, Ester Nin and Carles Ortiz began with 10 acres of vineyards in Finca les Planetes, where Carles restored old Garnatxa and Carinyena plantings. Ester—an enologist from the University of Barcelona—then bought a tiny three-acre parcel Garnatxa Negra, Garnatxa Peluda and Carinyena in Mas d’En Caçador, the famed vineyard on steepest hillside slopes between Porrera and Gratallops.

Ester Nin and Carles Ortiz, Família Nin-Ortiz

Since both Carles and Ester were early proponents of biodynamics in the Priorat, and since both lived in Porrera (and both were young and available), the stars aligned and Família Nin-Ortiz was born.

Says Ester, “We farm using exclusively organic materials, biodynamic infusions and our own compost. All the work is manual. Weeding is done by hand, and the soils are plowed by mules to revitalize their soils. Harvesting, always by hand, commences early when pH levels are balanced by ripe fruit.”

Once in the cellar (completed in 2012), Carles walks us through the process: “The fruit is carefully sorted to remove any overripe grapes and the bunches partially destemmed, then chilled for 24-48 hours to prevent oxidation. This begins the winemaking process. Fermentations occur spontaneously. Família Nin-Ortiz’s goal is to produce elegant wines, so extraction is also natural, occurring without aggressive manipulation of the cap. Aging takes place primarily in neutral vessels so the purity of the site can be preserved.”

Família Nin-Ortiz ‘Partida Les Planetes, Garnatxes’, 2021 Priorat-Porrera ($44)

Família Nin-Ortiz ‘Partida Les Planetes, Garnatxes’, 2021 Priorat-Porrera ($44)

100% Garnatxa harvested from the ten-acre Finca Les Planetes Porrera plot. Four weeks of maceration are followed by fermentation on wild yeasts and seven months of maturation with 10% in amphorae, resulting in a deep, floral-spicy, terroir-driven wine with a rock-solid, flinty schist-granite structure. 2700 bottles produced.

Família Nin-Ortiz, 2021 ‘Partida Les Planetes Clàssic’, 2021 Priorat-Porrera ($51)

Família Nin-Ortiz, 2021 ‘Partida Les Planetes Clàssic’, 2021 Priorat-Porrera ($51)

From young Garnatxa and Carinyena vines (10 – 20 years old) grown in Finca Les Planetes, one of the northeast-facing vineyards that Carles Ortiz purchased and renovated. Grapes are hand-harvested, partially destemmed, fermented on indigenous yeasts and aged in foudre and amphorae. The freshness and brightness of fruit from the Planetes site is a testament to the relatively cooler, northeast exposure of the site as well as the hands-off approach that Carles and Ester take in the cellar. The nose shows beautiful aromas of black cherry, plum and elderberry with hints of herbs, lavender, sage and balsam. 14,660 bottles produced.

Família Nin-Ortiz – Nit de Nin, 2021 Priorat-Porrera ‘Paratge Mas d’En Caçador – Velles Vinyes’ ($196)

Família Nin-Ortiz – Nit de Nin, 2021 Priorat-Porrera ‘Paratge Mas d’En Caçador – Velles Vinyes’ ($196)

A blend of Garnatxa, Garnatxa Peluda and Carinyena. At 2000 feet, Mas d’En Caçador is one of the highest plots in the Priorat and its north-facing slopes are pure blue and black schist soil. The vines are between 70 and 110 years old, and the wine shows multiple layers of sour cherry woven through hints of green plum, black olive and dark forest berries and a touch of cinnamon with plenty of balsamic savoriness on a long finish.

Família Nin-Ortiz, 2021 Priorat-Porrera ‘Paratge La Coma d’en Romeu – Velles Vinyes’ ($207)

Família Nin-Ortiz, 2021 Priorat-Porrera ‘Paratge La Coma d’en Romeu – Velles Vinyes’ ($207)

100% Garnatxa. Coma d’en Romeu is a warm, south-facing vineyard with an extremely steep slope where 70 to 100-year-old vines struggle on pure shale soil. Spontaneous fermentation of whole-bunches takes place in open wooden vats. Further aging takes place in 225 to 600-liter barrels. 2015 was the first vintage of this monovarietal which shows blackberry paste, fig jam, sweet smoke and mocha notes with lots of fragrant spices on the finish.

Família Nin-Ortiz, 2021 Priorat-Porrera ‘Paratge La Rodeda – Velles Vinyes’ ($283)

Família Nin-Ortiz, 2021 Priorat-Porrera ‘Paratge La Rodeda – Velles Vinyes’ ($283)

100% Garnatxa Peluda, a.k.a. ‘Hairy Grenache’—so named for the furry leaves that evolved to combat drought. The grapes are sourced from a single-vineyard called ‘Tros de la Tereisna i Daniel,’ a speck of a plot, smaller than an acre, where the vines are 80 years old and grow on black slate; these vines are certified as ‘Velles Vinyes’ by the DOQ (DOC) Priorat. Peluda wines tend to be lower in alcohol than other varieties of Garnatxa with moderate acidity; they are lighter on the palate with the potential for rapid oxidation. The wine is pleasantly meaty, fresh and slightly tannic with aromas of raspberry preserves and star anise. 304 bottles made.

Clos Petitona

Priorat Vi de Vila ‘Masos de Falset’

The northern part of the municipality of Falset is made up of land whose geology and climate were considered suitable to produce wines with the characteristics of the wines of Priorat; the largest portion is known as ‘Masos’ based on the number of farms and farm cottages where people live during the harvest.

Masos de Falset hillside composed of ‘Llicorella’ consisting of reddish-black slate with small particles of mica quartz, different layers of soil filled in by clayey soil. Clos Petitona winemaker Blai Ferré i Just, right

Núria Garrote i Esteve and winemaker Blai Ferré first collaborated on a wine project in 2013. Both natives of the area, Blai fell in love with winemaking while a teenager working the fields with one of Priorat’s leading producers, Álvaro Palacios. He then purchased a handful of acres, much of it former vineyard land that had been abandoned, and set to work planting drought-adapted rootstocks and adopting a style of under-extraction to better nurture these wines so that the dazzling minerality of Priorat’s smoky schist can shine through.

Clos Petitona (Little Ona) is produced from a single plot located in the village of Falset, and is typical of the extreme slopes of crumbled black slate (llicorella in Català), terraced against the ravages of time. It was planted in 1949 with equal parts Garnatxa Negra and Garnatxa Peluda vines, with a south-east orientation and a surface area just under four acres. Due to the age of the vines, yields are extremely low, giving the wines superb concentration and structure.

Clos Petitona, 2019 Priorat-Masos de Falset ($77)

Clos Petitona, 2019 Priorat-Masos de Falset ($77)

Despite a terrifying heatwave in late June that literally burnt grapes and damaged many Carinyena vines, 2019 in Priorat has been rated ‘excellent.’ Drought led to extremely low yields and high levels of concentration and a local producer summarized the season as ‘short, healthy, and quick, with the sorting table being used as a mere conveyor belt.’

Like the plot itself, Petitona is equal parts traditional Catalan Garnatxa Negra and Garnatxa Peluda. Perfumed rather than floral, the wine shows an earthen nose with baking spice and especially, a touch of licorice-ash, allowing the llicorella soil to live up to its name. 650 bottles produced.

Ona, 2021 Priorat ($23)

Ona, 2021 Priorat ($23)

2021 produced exceptionally fresh-tasting wines in the Priorat temperatures and rainfall aligned with the average and the crop was generous, although ripening was slightly delayed. Garnatxa was the star of the 2021 growing season; Carinyena, also a late-ripening variety, lacked the warmer conditions necessary to reach full phenolic maturity. Old vines with lower yields performed better.

A blend of 40% Garnatxa, 40% Syrah and 20% Carinyena 20% grown on Blai Ferré’s 12 acres; the wine is aged in stainless steel and shows ripe cherry and plum misted in smokiness, spice with wet-stone minerality on the finish. About 3000 bottles were produced.

Clos Petitona, Priorat – Vi de Vila ‘Masos de Falset’

Clos Mogador

Priorat Vi de Vila ‘Gratallops’

Overlooking the Siurana river, Gratallops lies in the heart of a licorella basin, irrigated on the either side by the Montsant river and the Siurana, with an average elevation above one thousand feet. A wisp of a village with about 250 inhabitants, it is a quaint and quiet stopover whose main strip includes a bakery, a grocery store and a ceramic workshop.

In 1979, Isabelle and René Barbier settled in this gentle region and set out to rediscover the forgotten vines of the region. They named the estate Clos Mogador in homage to Élisabeth Barbier, René Barbier’s aunt and author of ‘Les Gens de Mogador.’

The Barbier Family, Clos Mogador

(left to right) Christian Barbier Meyer, Anderson Barbier Meyer, René Barbier, Isabelle Meyer, René Barbier Meyer

The establishment of this estate can be credited with having jumpstarted the Priorat revolution.

“At Clos Mogador, a young French woman and a Catalan man have found the place of our dreams,” Barbier waxes: “A two-step between the dancer and the sensitivity and determination of a poetic philosopher. She artfully designs the future while I attempt to squeeze out the earth’s abundance from fruit.”

On a slightly more practical note he says, “We rely on use of indigenous varieties, especially Garnatxa and Carinyena for Clos Mogador and Manyetes wines. For fermentations, yeasts are natural obtained by spontaneous fermentation and the starter process using ‘pied de cuve’ from the bottom of the tank. Sulfur is dosed to a minimum to maintain a balance in microorganisms; fermentations are slow and the macerations long. The aging takes place according to our criteria, in cement tanks, old foudres, barrels, Dama-Juanas glass or ceramic jars.”

Isabelle adds, “It’s about giving more freedom to wine in its evolution. It is not that we seek perfection, but to express ‘the Priorat’ and to produce wines designed for aging but with sufficient complexity in their youth.”

Clos Mogador, 2016 Priorat-Gratallops ‘Manyetes’ ($99)

Clos Mogador, 2016 Priorat-Gratallops ‘Manyetes’ ($99)

100% Carinyena. According to René Barbier: “Manyetes is the name of a vineyard in Gratallops, a daring venture where vines can barely survive given the poor soil of the region, the intense sunlight and the bleak exposure. The vines are quite literally at the extreme of survival, however, this is exactly what gives rise to the principal essence of Priorat!”

The wine displays intense aromas of Bing cherries and summery raspberries combined with mineral notes of flint, and botanical hints of eucalyptus, tobacco and coffee beans. 4700 bottles made.

Notebook …

(Climate) Change Is Afoot in Catalunya

With apologies to Professor Higgins, the rain in Spain is not only dodging the plains, it’s playing havoc up and down the entire Mediterranean coast, extending from Spain to North Africa and Sicily as well. Last year, this persistent drought ranked among the ten most costly climate disasters in the world, and in real time, Catalunya is undergoing the worst drought in a century, with water reserves at 16% of capacity. Hotels are filling swimming pools with seawater and those whose livelihoods are tied to agriculture are wondering what the intensity of this summer will bring; last year, fruit growers threw out entire crops in order to use their diminishing water supplies to save their trees. Even traditionally dry-farmed industries like olive production and wine growing are crippled by these severe heat waves, and farmers who irrigate have it even worse, since by law, they are the first ones to relinquish water rights.

Adaptation to the climate crisis is happening throughout Catalunya; there is no other choice. But to date, much of it improvised and tends to take place only when the worst has already happened. Like the old Inuit following the caribou, modern winemakers are being forced to follow the thermometer, and this has led to an exploration of vineyard space in regions that were once too cold to produce reliable harvests.

- - -

Posted on 2024.10.17 in France, Priorat DOQ, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

The High Priestess of Biodynamics: Françoise Bedel, a Passionate Advocate of the Practice, Unlocks Meunier’s Potential in Champagne’s Rot and Frost-Prone Western Fringe. 4-Bottle Sampler Pack $399

In a small estate that is closer to Paris than to Reims, Françoise Bedel has managed a remarkable feat: She has turned an acute family illness into a paradigm shift for much of the Champagne region.

From the village of Crouttes-sur-Marne, nestling the banks of the Marne River, Bedel discovered homeopathic medicine while trying to find a cure for her son Vincent’s hitherto untreatable condition. Vincent, now her winemaker, made a marked improvement, and this how Françoise’s journey to biodynamic viticulture began. In 1982, at a time when virtually no one in the wine world had even heard about it, let alone employed it, she realized that the health of the body and the health of the vineyard may be interchangeable concepts.

She says, “Biodynamics is way of thinking—about the earth, about ourselves, about wine.”

This month’s Champagne package is the output of such iconoclastic thinking—and the tale of wrenching victory from the jaws of illness, cold clay and climate change.

The Vallée de la Marne: Twists and Turns, Patchwork of Soils

In strictly geographical terms, the Marne Valley extends from the city of Tours-sur-Marne to Château-Thierry. It stretches over sixty miles and through two départements, the Marne and the Aisne, all the way to the limits of Seine-et-Marne. As its name indicates, the Marne Valley follows the river, a landscape of rolling hills and small villages. Vines are planted on both banks although those on the north side benefit from a more favorable southern to eastern sun exposure.

The most famous villages are located at the eastern end of the valley around the city of Épernay, a ranking that reflects the importance given to the presence of chalk in the soil. Chardonnay and Pinot Noir dominate the vineyards of the eastern end of the region, and the major Champagne houses located here include Billecart-Salmon or Philiponnat in Mareuil-sur-Aÿ, Deutz and Bollinger at Aÿ and Jacquesson in Dizy.

West of Châtillon-sur-Marne, chalk tends to be found more deeply buried in the ground; the top soil is made of calcareous clay and clay marls. Meunier is the grape of choice in this part of the valley and it here that a new generation of experimental winemaker has flocked in order to deepen their own (and by proxy) our understanding of this variety.

Downriver in Champagne’s Western Fringe: Clay Descends Deeper

The farther west you go in Vallée de la Marne, the thicker the clay deposits become and the more contentious the weather grow; cold air sinks and follows the snaking river. It is in this somewhat inhospitable condition that Meunier begins to show its mettle. An also ran in much of Champagne, here it is king; among the 21,000 acres of Vallée de la Marne vineyard, especially in the west, about 72% is Meunier.

Although Pinot Noir and Chardonnay can both do well with less chalk and more marl, it is the triple threat of valley frost, fog and cooler, clay-heavy soil that tilts the scale towards Meunier. It also helps that the grape is a tad more resistant to botrytis than Pinot Noir or Chardonnay, along the host of other mildews that thrive in the damp, humid conditions encouraged by morning fogs that follow the river.

Meunier Comes into Focus

A light juice and dark skin grape, Meunier tends to be considered the inferior of the three dominant grapes of Champagne, without the finesse, the liveliness or the delicateness of its illustrious counterparts, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Lately, Meunier has been experiencing a comeback and many up-and-coming winemakers are showcasing it in their range. 100% Meunier cuvées are becoming more common and single vineyard Meunier releases are available. In Baslieux-sous-Châtillon, Eric Taillet even launched the ‘Meunier Institut’, entirely dedicated to his (and Françoise Bedel’s) favorite grape.

Champagne Françoise Bedel

Original in Personality, Intensely Soil-Expressive

“For a wine to truly express terroir,” says Françoise Bedel, “one must respect the land’s qualities and characteristics as you would an individual’s personality.”

The 22 acres that make up Champagne Françoise Bedel are spread out on either side of the Marne, Crouttes-Sur-Marne, Nanteuil-Sur-Marne, Charly-Sur-Marne, and Villiers-Saint-Denis. Here vines are between 30 and 70 years old (79 percent meunier) and each plot boasts different subsoils, allowing for blending according to the terroirs and the elaboration of terroir-specific cuvées.

Françoise Bedel and son Vincent

“These Champagnes are the expression of a rigorous method that brings out and enhances the qualities and particularities of the earth, the vines and the fruit,” Bedel says. “Because I love plants, life in contact with nature, and passing on a healthy land to the next generations, I have been cultivating my vineyard organically since 1998 on the entire estate.”

She is, in fact, only the second generation to tend these vineyards. Her parents, Fernand and Marie-Louise Bedel, turned over a portion of the estate to her in 1979 and with her son Vincent Desaubeau, who has now taken over as winemaker, she forges the future.

The key to the Bedel style is long lees aging, regardless of whether it is vintage or non-vintage; all cuvées go through at least 36 months on the lees in the cellars but more often than not, the wines are not released sooner than five years after harvest, offering pure, assertive flavors with a slight oxidation, equating to some of the finest expressions of Meunier in Vallée de la Marne, and arguably, the world.

Old Soils, New Farming

Compared to much of northern France, especially in the Paris Basin, the soil of Vallée de la Marne is still wet behind the eras. The further from the center of the basin, the older the deposits; Alsace and Burgundy, Metz and Dijon lie largely on Jurassic soils from between 150 and 200 million years old. Champagne, near the center of the depression, sits on soils between about 40 and 150 million years of age.

To this ancient earth Champagne Françoise Bedel brings innovative biodynamics, often numbered by ‘preparation’ and applied at various times in the lunar cycle.

Preparation 500, for example, is a manure concoction that reinforces subterranean biodiversity; vine roots lengthen, deepen and spread more densely and evenly in the soil. Preparation 501 is made of powdered quartz buried inside a cow’s horn, said to help in leaf development and initiating blossoming—it is applied early in the morning, at sunrise. Preparation Maria Thun is a compost of dynamized cow manure, reinforces the process of decomposition. According to Françoise Bedel, “All its ingredients contribute to the development of complex humus clay. A large number of microorganisms improves soil life. After years of research, Maria Thun [a German biodynamics authority who passed away in 2012] was able to document the cosmic influences on plants. The sun, the moon and all the other planets influence in their own manner life on this Earth, be it vegetal, animal, or human.”

Making Wine: Unlocking the Potential

Says Françoise Bedel: “Following my intuition, I propose Champagnes with a strong personality, which beyond being a media lure, has the potential to be a medium at the service of your well-being.”

Unlocking that potential has been the driving force behind the estate’s operations, field to cellar, by the day and by the decade. Nearly everything is done by taste and to pay homage to taste. As Françoise explains, “The date of the harvest is decided after tasting the grapes and analyzing the must from grapes that have just been pressed. The pressing operation is carried out entirely at the domain; a good pressing preserves the potential longevity of the wine by being carried out in a gentle manner. The fractioning of the juice from the different grape varieties and terroirs allows for an additional selection, again, by taste alone.”

She goes on: “We further unlock the potential of the harvest by vinifying partially in oak barrels to reinforce the richness and the aromatic complexity. The other part is vinified in small enameled vats to enhance the purity of the terroirs. The contents of each vat are clearly identified by the parcel of land and the racking is carried out under conditions that are in keeping with Maria Thun’s lunar calendar.”

Blending: A Leap into the Future

As a painter chooses his pigments or composer writes a symphony with various instruments in harmony, the assemblage of a Champagne maker must take all elements, the obvious and the subtle, into consideration. And more: The essential notes of symphony will not change with time and the paintings in the Louvre are the same ones once viewed by our great grandparents. Wine, however, is a mutable substance, ever undergoing the ravages or the enhancements of time.

Rather than paint or musical notes, the raw material of wine is geology, exposure, place of origin and specific parcels contribute to the organoleptic qualities of grape juice. The marriage of aromatics and flavors to create a synergistic whole is the art of the cellar master; many tests are carried out and multiple opinions gathered before proceeding with final blends. These decisions are critical since the outcome is irreversible and unique, intended to express the personality and preferences of the winemaker.

“The actual blending is a leap into the future,” says Françoise. “In point of time, it is never rushed; it can take from a few days to a few weeks.”

Bedel’s Multi-Village Champagne

The villages of Champagne each carry with them individual stories—some approaching a legendary status; 319 of them, under the system called the Échelle des Crus, are rated on a scale with ascending degrees of excellence. A winemaker, following strictures, may label Champagne with the name of a specific village or combine several in the foundational regional concept of blends.

•1• Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Origin’elle’, Brut ($91)

•1• Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Origin’elle’, Brut ($91)

• 80% Meunier, 15% Chardonnay, 5% Pinot Noir

• Harvested in 2016 plus small amounts of vins de réserve

• From 30-60-year-old vines

• 95% stainless steel and 5% oak barrel aging

• 4 years sur-lattes

• Disgorged in July 2021 and dosed at 4.35 grams

The combination of terroirs—silty limestone and calcareous clay—produces a nuanced Champagne that emphasizes crisp primary fruit flavors. It is fermented in enamel-lined steel tanks and neutral French oak barrels and sees 3 years of aging ‘sur latte’ before disgorgement. A ripe Champagne where freshly-sliced apple notes are cut with citrus and a tangy undertow gives the wine’s texture a necessary bite.

Bedel’s Site-Specific Expressions

Traditionally, of course, Champagne is a blend of wines from a particular year, often from separate plots, mixed with reserve wines from previous harvests. This is a technique which has allowed a winemaker to ensure that his wine has a certain taste stability—a house style that remains constant from one year to the next. Otherwise, as in much of the wine world, a label tends to reflect only an estate while the product changes in taste and quality depending on the year and the climate.

Plot specific wines, known as lieux-dits in Burgundy, are based on the theory that certain groupings of vines have unique characteristics that directly influence the development and aromatic concentration of the grapes. These are usually natural conditions specific to the vineyard location, such as its orientation, the presence of a forest or a mineral outcrop on the surface. In Champagne, a ‘clos’ is usually a walled-off portion of a vineyard identified by a winegrower for its natural potential. This artificial barrier creates a microclimate specific to this plot which will, over the years, develop its own aromatic identity. Given these specificities, one can better understand why many of the winegrowers who are lucky enough to own such plots of land decide to produce cuvées that are parcel-based and very often vintage wines.

•2• Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Dis, “Vin Secret”‘, Extra-Brut ($140)

•2• Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Dis, “Vin Secret”‘, Extra-Brut ($140)

• 70% Meunier, 25% Pinot Noir, 5% Chardonnay

• Harvested in 2018 plus small amounts of vins de réserve

• From 30 to 70-year-old vines

• 100% stainless steel aging

• 4 years sur-lattes

• Disgorged in June 2023 and dosed at 11.75 grams (the highest I’ve ever seen from Bedel)

Dis, “Vin Secret” Extra Brut showcases the delicate fruitiness of Pinot Meunier grown on heavier silts and clays then aged ‘sur latte’ to the point where the primary fruit is in perfect harmony with the wine’s autolytic expression. While frequently released as a 100% bottling of Meunier, this year Vincent added 25% Pinot Noir and 5% Chardonnay and dosed it with an unusually high percentage of sugar.

•3• Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Entre Ciel & Terre’, Harvest 2015, Extra-Brut ($125)

•3• Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Entre Ciel & Terre’, Harvest 2015, Extra-Brut ($125)

• 50% Pinot Noir, 35% Meunier, 15% Chardonnay

• 100% from 2015

• From 30 to 70-year-old vines

• 100% stainless steel aging

• 3 years sur lattes

• Disgorged in June 2021 and dosed at 4.20 grams

‘Between heaven and earth’ is a fine name for a biodynamic wine originating in vineyards planted on calcareous clay soils. It is aged 5 years ‘sur latte’ and bottled with a modest dosage, to show aromas of wildflowers, green olive and bright cranberry; upon opening, a deeper nose displays a complex layer of rosemary, white pepper and a touch of forest floor.

Bedel’s Vintage Champagne

No mumbo-jumbo wine lexicography here; vintage Champagne is made from the harvest of a single year. As it is generally only made in superior vintages, frequently only three to four times every decade, it may fairly be viewed as an indicator of quality.

•4• Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘L’Âme de la Terre’, 2008 Extra-Brut ($117)

•4• Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘L’Âme de la Terre’, 2008 Extra-Brut ($117)

• 50% Chardonnay, 30% Pinot Noir, 20% Meunier

• 2008 vintage

• From 30 to 60-year-old vines

• 65% stainless-steel and 35 % oak barrel aging

• 14 years sur-lattes

• Disgorged in June 2023 and dosed at 10.35 grams

L’Âme de la Terre is a vintage-dated champagne grown entirely on calcareous clay soils and fermented in a combination of enameled stainless-steel tanks and French oak barrels. It is aged ‘sur-latte’ for 14 years before disgorgement and finished with a serious dosage of 10.35 grams. The wine shows luscious ripe apple, and a bit of marzipan behind a mouthwatering minerality.

Notebook …

Champenois Radicalism: The Emergence of Vignerons and Micronégociants

First, a somewhat inconvenient truth: If asked what the term ‘négociant’ means, the honest answer is ‘nothing.’ Some négociant buy grapes, some mature wine, and some simply put their name on the label. Some, like Olivier Leflaive, dislike the term entirely: “I see myself as a winemaker, not a négociant, as I make the wine, from the beginning of vinification through to bottling.”

More than half of Burgundy is made by négociants whose average size is ten times that of the average domain. In Champagne, it is a different story; complicated local economics, long in thrall to massive companies, is shifting its prestige dynamics toward individual vignerons. The most earth-shattering paradigm shift in this approach is seen in the emergence of artisan styles in a region where uniformity has long been the key to success.

Into this swirl of radical rethinking comes the micronégociant. The name refers not only to their size (generally much smaller than the traditional négociant) but to the fact that many purchase grapes while continuing to farm them. Says Jean-Hervé Chiquet of Jacquesson, who farms 69 acres and purchases fruit from seven more: “We’re vignerons who buy a lot of grapes or we’re négociants who grow a lot of grapes. You decide.”

In Champagne, where a prime hectare (2.5 acres) of vineyard may cost over a million euros, few banks will lend a young grower the money to buy land, but a micronégociant can purchase barrels here and there—a typical entry route for newcomers who did not inherit an estate, or for those who want to extend a small family domain.

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

To be Champagne is to be an aristocrat. Your origins may be humble and your feet may be in the dirt; your hands are scarred from pruning and your back aches from moving barrels. But your head is always in the stars.

As such, the struggle to preserve its identity has been at the heart of Champagne’s self-confidence. Although the Champagne controlled designation of origin (AOC) wasn’t recognized until 1936, defense of the designation by its producers goes back much further. Since the first bubble burst in the first glass of sparkling wine in Hautvillers Abbey, producers in Champagne have maintained that their terroirs are unique to the region and any other wine that bears the name is a pretender to their effervescent throne.

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

The lauded wine writer Peter Liem expands the number of sub-regions from four to seven, dividing the Vallée de la Marne into the Grand Vallée and the Vallée de la Marne; adding the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay and combining the disparate zones between the heart of Champagne and Côte de Bar into a single sub-zone.

Courtesy of Wine Scholar Guild

Lying beyond even Liem’s overview is a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that compliment or contrast when final cuvées are created.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Épernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

… Yet another reason why this tiny slice of northern France, a mere 132 square miles, remains both elite and precious.

Three Primary Varieties and Four Heirloom Grapes

Champagne, with few exceptions, is a blended wine. Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Meunier are the trinity that form the bulk of these blends; a handful of heirloom grapes that have official government sanction in certain locations within the AOP.

Although they make up fewer than 0.3% of planted acres, with the dramatics being wrought by climate change, these other varieties may find a more prominent role in future blends:

Arbane is a late-ripening variety that succumbs easily to bad weather, and yet—under ideal conditions—produces a Champagne with remarkable finesse, offering nuanced notes of hawthorn blossom and carnation and as well as peach, apple and quince.

Petit Meslier is another milktoast variety, highly susceptible to disease and frost. But when it produces, it does so with both barrels, bringing a smoky quality to the wine that makes it identifiable, even when used in small quantities.

Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc, both white cousins to red Pinot Noir are low in acidity and somewhat easier to work with than Arbane or Meslier, although like Pinot Noir, Gris may be somewhat finicky. Both bring to blend their own magic; Gris offers a nutty quality to the finished wine and Pinot Gris adds punch and body.

- - -

Posted on 2024.10.04 in France, Wine-Aid Packages, Champagne | Read more...

In the Cradle of Malbec: Husband and Wife Team Matthieu Cosse and Catherine Maisonneuve’s Cahors Wines Show Uncommon Finesse and Elegance While Retaining Power 5-Bottle Sampler Pack $127

Recently, Elie Wine Co. had the good fortune of hosting author, speaker, wine educator and videographer Dr. Matt Horkey, who was kind to film a segment for his YouTube channel right here in the shop. Entitled ‘Why is French Wine so Intimidating?’ he explored the evolving tastes of consumers (and himself) when it comes to the world’s most heralded wine region.

Although the question Dr. Matt asks is personally rhetorical (he is something of an expert on the subject of French wine), the video was a good chance for us to rehash some of the common misconceptions and stereotypes that the average consumer may have, and it was an opportunity for me to hone my approach to wine lovers who are looking to expand both their knowledge and experience in the world of French wine.

Dr. Matt is on a crusade to make wine fun and non-intimidating: “Wine is a treasure hunt, and we should treat it like that,” Dr. Matt maintains during our 42-minute video segment. “The fun is in the search, the process, not just in finding the best wine.”

Dr. Matt, who has a particular love for small producers and limited run wines, found plenty to love on our shelves, since finding and making these gems available is a large part of our mission statement.

Subscribe to his YouTube channel and check out the interview along with numerous other excellent wine videos.

https://youtu.be/LwAqnzQgqvw?si=O1-qFQLHGv1pPAIL

Had ‘Steinbeck’ been ‘Malbec’, his grapes might have had less wrath. Forgive the awful pun, but within the world of Malbec, the more you take things seriously, the more perplexing the curve-ball seems to be. The mainstay of its natural home in Southwest France, Malbec found greener commercial pastures a hemisphere away in Argentina—a country that now produces ten times as much Malbec as Cahors. And in Malbec’s home field, land remains dirt cheap compared to much of French wine country; a hectare of land will go for $10,000 whereas in Burgundy, you could add a couple zeros to that figure and still come up short.

And yet, of Cahors’ 50,000 arable vineyard acres, four-fifths lie fallow.

This week’s recent arrival package highlights a pair of remarkable winemakers who have helped Cahors rise above itself and its somewhat flagging reputation—a casualty of wars, frost and consumer tastes. Fifteen years ago, Matthieu Cosse and Catherine Maisonneuve took over a 12-acre estate in Prayssac, a short distance from Cahors, planted with old vines of Malbec, and set out to make wines that are the antithesis of the rustic image of the region. Their portfolio of wines has proven to be uncommonly elegant and round, a ‘renaissance’ style that Cosse and Maisonneuve credit, in part, to climate change, which has brought to the Cahors’ limestone uplands greater vintage regularity.

“Marginal sites here may still produce acidic Malbec wines, even if picked into October,” says Cosse, “but the shifting tides of climate are greening up the pastures of Cahors.”

The Southwest: France’s Hidden Corner

How France’s fifth-largest winegrowing region remains one of its least known (and mostly underappreciated) is another mystery. Tucked away between the Pyrenees mountains in the South, Bordeaux in the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, France’s ‘Hidden Corner’ has twice as many vineyards as Burgundy and boasts some of France’s most beautiful countryside with vineyards scattered across rolling fields and picturesque river valleys.

Roughly divided into four sub-regions, each area has its own personality and unique wine profile: Bergerac and Dordogne, which specializes in dry white blends, full-bodied reds and sweet dessert wines; the Pyrenees, known for rustic Tannat, the variety that dominates the area’s most renowned appellation, Madiran; Garonne and Tarn, famous more for breathtaking scenery that top shelf wine and Lot, home to the incomparable Malbec-based ‘Black Wines’ of Cahors.

Cahors: ‘Lot’ Runs Through It

While the Colorado River was busy carving out the Grand Canyon, a similar, if slightly less dramatic geological phenomenon was happening in Southwest France, where the Lot River was at work creating the Lot Valley, where, instead of leaving behind a big hole, there are steeped terraces ideal for vine cultivation. The terroir of Cahors is loosely defined by the differing soil types and the exposures created by these terraces.

The Plateau, referred to ‘les Causses’, lies at an elevation of nearly a thousand feet; it contains the Kimmeridgian limestone also found in Chablis and parts of Champagne. In addition, this area holds layers of iron rich clays with sporadic patches of rare blue clay, lending structure and energy to the wines. Below that, the Fourth Terrace, at an average elevation of 788 feet, offers a mix of limestone scree and ancient alluvial soils from the river, creating wines with bright red fruit and rustic earthiness. The Third Terrace is closer to the river, and at an average elevation of 558 feet it is primarily composed of clay, sand and the famous ‘galets roulés’ which imbue the wines with bold, black fruit and supple tannins, adding roundness in the way that Merlot softens Cabernet Sauvignon in Bordeaux.

Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve

Individually, their pedigrees are impressive: Matthieu, Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve’s winemaker, is a graduate of the Institute of Enology in Bordeaux, and Catherine, the oenologist, holds a BTS viticulture and oenology from Blanquefort. Together, Matthieu and Catherine make magic. In 1999, they took over a 12-acre estate of old Malbec vines in Prayssac, a short distance from Cahors, and set out to make wines intended to transcend the rustic image of Cahors. Their first vintage was ‘Les Laquets’ and they shortly expanded the range to include separate cuvées intended to reflect the identity of the different terroirs of the estate.

Catherine Maisonneuve and Matthieu Cosse, Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve

Says Catherine: “Wine is the ambassador of a terroir and a winemaker is the interpreter. Thus, to obtain perfect grapes that will clearly express the qualities of the Cahors terroir, everything in the vineyard must be natural.”

As such, they are certified organic by Ecocert and farm their vineyards biodynamically with a plan to become Demeter certified as well. Everything done in the vineyard aims at building of balanced soils to produce optimal conditions for ripening the grapes and making harmonious, aromatically complex and precise wines. Today, Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve totals 42 acres planted predominantly to Malbec, with small amounts of Merlot and Tannat.

All plots are situated in primary locations on the gravel and clay Third Terrace above the Lot River.

1 Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve ‘Solis’, 2019 Cahors ($16)

1 Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve ‘Solis’, 2019 Cahors ($16)

Cosse et Maisonneuve puts a new twist on the old school wines of Cahors, relishing in a style that is precise and elegant, smooth and aerial. Produced from a 25-acre plot in the commune of Mauroux from the ‘lightest’ section of the terrace dominated with gravel and alluvial sediment, it was de-stemmed and vinified in vats to preserve its velvety character. It shows pure varietal aromas and flavors of blueberry and violet behind silky tannins, with hints of herbs in the finish. An exceptionally high quality wine for the price, from some of the most meticulously farmed vineyards in the region.

2 Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve, 2021 ‘Le Combal’ Cahors ($22)

2 Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve, 2021 ‘Le Combal’ Cahors ($22)

A beautiful example of the ‘new’ Cahors—a finer-grained and elegant Malbec which sacrifices none of the variety’s iron-scented power and structure of traditional Cahors, but focuses on fruit. Black currant and cherry shine through notes of pipe smoke, clay and bitter herbs with tannins that are woven through without a sense of dominance.

3 Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve, 2021 ‘La Fage’ Cahors ($26)

3 Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve, 2021 ‘La Fage’ Cahors ($26)

Still in the bloom of youth, ‘La Fage’ has nose lush with macerated black currant, blackberry and plum. The mouth-coating tannins may require a little more time to settle in, but it is on its way—cellar this wine or drink it tonight with a well-marbled piece of beef.

4 Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve ‘Les Laquets’, 2019 Cahors ($45)

4 Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve ‘Les Laquets’, 2019 Cahors ($45)

A perfect representation of the Cosse/Maisonneuve style—elegant, complex and biodynamic, from vines that are over fifty years old. The palate is dense yet sleek, with notes of blackberry, fennel and iris behind grippy tannins. 2019 was an extraordinary vintage with superb aging potential.

5 Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve, 2022 ‘Cheval en Tête’ VdF Southwest-Cahors Blanc ($18) WHITE

5 Domaine Cosse et Maisonneuve, 2022 ‘Cheval en Tête’ VdF Southwest-Cahors Blanc ($18) WHITE

70% Ugni Blanc, and a 30% blend of Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc. The wine shows bright grapefruit-infused bitters along with floral and honey notes, finishing with a slight smokiness that resolves in a citrus bite.

Notebook …

Cahors vs. Argentina: The Expression of the Malbec Grape

Same grape, different day. When, in the mid-nineteenth century, French agronomist Miguel Pouget was hired by the governor of Mendoza to create a training program for winemakers in Argentina, he brought along 120 French varietals. Of them, one proved to be a first among equals.

In France, Malbec tends to be a problem child as it particularly susceptible to frost and dampness. In Argentina, growing Malbec proved to be almost too easy: By 1944, when Argentina had over 250,000 acres of vines planted, half of them were Malbec. At the time, the general population of the South American country preferred quaffable table wines, and a lot of Malbec wound up as a supplement to add color and aroma to native grapes, called ‘criollas.’

As tastes evolved, so did Malbec. Today, Argentine Malbec has smaller grapes and tighter bunches than the type grown in Cahors, and the flavor profile is markedly different. It turns out that Malbec enjoys the heat, and thrives on the unique minerals in Argentine soils as well as the cooling air flowing down from the snow-capped Andes Mountains. The wines are less ‘sledgehammer’ and more plummy and fruit-forward than their French counterparts, which tend to be austere and astringent in their youth, maturing to showcase a leathery, savory bitterness often highlighted by black pepper and spice.

And as the French are fond of saying, “Vive la différence.”

- - -

Posted on 2024.10.03 in Cahors, France, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

The Champagne Society October 2024 Bimonthly Selection: Françoise Bedel

The High Priestess of Biodynamics

Françoise Bedel, a Passionate Advocate of the Practice,

Unlocks Meunier’s Potential in Champagne’s Rot and Frost-Prone Western Fringe

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Entre Ciel & Terre’, Harvest 2015, Extra-Brut ($105)

In a small estate that is closer to Paris than to Reims, Françoise Bedel has managed a remarkable feat: She has turned an acute family illness into a paradigm shift for much of the Champagne region.

From the village of Crouttes-sur-Marne, nestling the banks of the Marne River, Bedel discovered homeopathic medicine while trying to find a cure for her son Vincent’s hitherto untreatable condition. Vincent, now her winemaker, made a marked improvement, and this how Françoise’s journey to biodynamic viticulture began. In 1982, at a time when virtually no one in the wine world had even heard about it, let alone employed it, she realized that the health of the body and the health of the vineyard may be interchangeable concepts.

She says, “Biodynamics is way of thinking—about the earth, about ourselves, about wine.”

This month’s Champagne package is the output of such iconoclastic thinking—and the tale of wrenching victory from the jaws of illness, cold clay and climate change.

The Vallée de la Marne: Twists and Turns, Patchwork of Soils

In strictly geographical terms, the Marne Valley extends from the city of Tours-sur-Marne to Château-Thierry. It stretches over sixty miles and through two départements, the Marne and the Aisne, all the way to the limits of Seine-et-Marne. As its name indicates, the Marne Valley follows the river, a landscape of rolling hills and small villages. Vines are planted on both banks although those on the north side benefit from a more favorable southern to eastern sun exposure.

The most famous villages are located at the eastern end of the valley around the city of Épernay, a ranking that reflects the importance given to the presence of chalk in the soil. Chardonnay and Pinot Noir dominate the vineyards of the eastern end of the region, and the major Champagne houses located here include Billecart-Salmon or Philiponnat in Mareuil-sur-Aÿ, Deutz and Bollinger at Aÿ and Jacquesson in Dizy.

West of Châtillon-sur-Marne, chalk tends to be found more deeply buried in the ground; the top soil is made of calcareous clay and clay marls. Meunier is the grape of choice in this part of the valley and it here that a new generation of experimental winemaker has flocked in order to deepen their own (and by proxy) our understanding of this variety.

Downriver in Champagne’s Western Fringe: Clay Descends Deeper

The farther west you go in Vallée de la Marne, the thicker the clay deposits become and the more contentious the weather grow; cold air sinks and follows the snaking river. It is in this somewhat inhospitable condition that Meunier begins to show its mettle. An also ran in much of Champagne, here it is king; among the 21,000 acres of Vallée de la Marne vineyard, especially in the west, about 72% is Meunier.

Although Pinot Noir and Chardonnay can both do well with less chalk and more marl, it is the triple threat of valley frost, fog and cooler, clay-heavy soil that tilts the scale towards Meunier. It also helps that the grape is a tad more resistant to botrytis than Pinot Noir or Chardonnay, along the host of other mildews that thrive in the damp, humid conditions encouraged by morning fogs that follow the river.

Meunier Comes into Focus

A light juice and dark skin grape, Meunier tends to be considered the inferior of the three dominant grapes of Champagne, without the finesse, the liveliness or the delicateness of its illustrious counterparts, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Lately, Meunier has been experiencing a comeback and many up-and-coming winemakers are showcasing it in their range. 100% Meunier cuvées are becoming more common and single vineyard Meunier releases are available. In Baslieux-sous-Châtillon, Eric Taillet even launched the ‘Meunier Institut’, entirely dedicated to his (and Françoise Bedel’s) favorite grape.

Champagne Françoise Bedel

Original in Personality, Intensely Soil-Expressive

“For a wine to truly express terroir,” says Françoise Bedel, “one must respect the land’s qualities and characteristics as you would an individual’s personality.”

The 22 acres that make up Champagne Françoise Bedel are spread out on either side of the Marne, Crouttes-Sur-Marne, Nanteuil-Sur-Marne, Charly-Sur-Marne, and Villiers-Saint-Denis. Here vines are between 30 and 70 years old (79 percent meunier) and each plot boasts different subsoils, allowing for blending according to the terroirs and the elaboration of terroir-specific cuvées.

Françoise Bedel and son Vincent

“These Champagnes are the expression of a rigorous method that brings out and enhances the qualities and particularities of the earth, the vines and the fruit,” Bedel says. “Because I love plants, life in contact with nature, and passing on a healthy land to the next generations, I have been cultivating my vineyard organically since 1998 on the entire estate.”

She is, in fact, only the second generation to tend these vineyards. Her parents, Fernand and Marie-Louise Bedel, turned over a portion of the estate to her in 1979 and with her son Vincent Desaubeau, who has now taken over as winemaker, she forges the future.

The key to the Bedel style is long lees aging, regardless of whether it is vintage or non-vintage; all cuvées go through at least 36 months on the lees in the cellars but more often than not, the wines are not released sooner than five years after harvest, offering pure, assertive flavors with a slight oxidation, equating to some of the finest expressions of Meunier in Vallée de la Marne, and arguably, the world.

Old Soils, New Farming

Compared to much of northern France, especially in the Paris Basin, the soil of Vallée de la Marne is still wet behind the eras. The further from the center of the basin, the older the deposits; Alsace and Burgundy, Metz and Dijon lie largely on Jurassic soils from between 150 and 200 million years old. Champagne, near the center of the depression, sits on soils between about 40 and 150 million years of age.

To this ancient earth Champagne Françoise Bedel brings innovative biodynamics, often numbered by ‘preparation’ and applied at various times in the lunar cycle.

Preparation 500, for example, is a manure concoction that reinforces subterranean biodiversity; vine roots lengthen, deepen and spread more densely and evenly in the soil. Preparation 501 is made of powdered quartz buried inside a cow’s horn, said to help in leaf development and initiating blossoming—it is applied early in the morning, at sunrise. Preparation Maria Thun is a compost of dynamized cow manure, reinforces the process of decomposition. According to Françoise Bedel, “All its ingredients contribute to the development of complex humus clay. A large number of microorganisms improves soil life. After years of research, Maria Thun [a German biodynamics authority who passed away in 2012] was able to document the cosmic influences on plants. The sun, the moon and all the other planets influence in their own manner life on this Earth, be it vegetal, animal, or human.”

Making Wine: Unlocking the Potential

Says Françoise Bedel: “Following my intuition, I propose Champagnes with a strong personality, which beyond being a media lure, has the potential to be a medium at the service of your well-being.”

Unlocking that potential has been the driving force behind the estate’s operations, field to cellar, by the day and by the decade. Nearly everything is done by taste and to pay homage to taste. As Françoise explains, “The date of the harvest is decided after tasting the grapes and analyzing the must from grapes that have just been pressed. The pressing operation is carried out entirely at the domain; a good pressing preserves the potential longevity of the wine by being carried out in a gentle manner. The fractioning of the juice from the different grape varieties and terroirs allows for an additional selection, again, by taste alone.”

She goes on: “We further unlock the potential of the harvest by vinifying partially in oak barrels to reinforce the richness and the aromatic complexity. The other part is vinified in small enameled vats to enhance the purity of the terroirs. The contents of each vat are clearly identified by the parcel of land and the racking is carried out under conditions that are in keeping with Maria Thun’s lunar calendar.”

Blending: A Leap into the Future

As a painter chooses his pigments or composer writes a symphony with various instruments in harmony, the assemblage of a Champagne maker must take all elements, the obvious and the subtle, into consideration. And more: The essential notes of symphony will not change with time and the paintings in the Louvre are the same ones once viewed by our great grandparents. Wine, however, is a mutable substance, ever undergoing the ravages or the enhancements of time.

Rather than paint or musical notes, the raw material of wine is geology, exposure, place of origin and specific parcels contribute to the organoleptic qualities of grape juice. The marriage of aromatics and flavors to create a synergistic whole is the art of the cellar master; many tests are carried out and multiple opinions gathered before proceeding with final blends. These decisions are critical since the outcome is irreversible and unique, intended to express the personality and preferences of the winemaker.

“The actual blending is a leap into the future,” says Françoise. “In point of time, it is never rushed; it can take from a few days to a few weeks.”

Bedel’s Multi-Village Champagne

The villages of Champagne each carry with them individual stories—some approaching a legendary status; 319 of them, under the system called the Échelle des Crus, are rated on a scale with ascending degrees of excellence. A winemaker, following strictures, may label Champagne with the name of a specific village or combine several in the foundational regional concept of blends.

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Origin’elle’, Brut ($91)

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Origin’elle’, Brut ($91)

• 80% Meunier, 15% Chardonnay, 5% Pinot Noir

• Harvested in 2016 plus small amounts of vins de réserve

• From 30-60-year-old vines

• 95% stainless steel and 5% oak barrel aging

• 4 years sur-lattes

• Disgorged in July 2021 and dosed at 4.35 grams

The combination of terroirs—silty limestone and calcareous clay—produces a nuanced Champagne that emphasizes crisp primary fruit flavors. It is fermented in enamel-lined steel tanks and neutral French oak barrels and sees 3 years of aging ‘sur latte’ before disgorgement. A ripe Champagne where freshly-sliced apple notes are cut with citrus and a tangy undertow gives the wine’s texture a necessary bite.

Bedel’s Site-Specific Expressions

Traditionally, of course, Champagne is a blend of wines from a particular year, often from separate plots, mixed with reserve wines from previous harvests. This is a technique which has allowed a winemaker to ensure that his wine has a certain taste stability—a house style that remains constant from one year to the next. Otherwise, as in much of the wine world, a label tends to reflect only an estate while the product changes in taste and quality depending on the year and the climate.

Plot specific wines, known as lieux-dits in Burgundy, are based on the theory that certain groupings of vines have unique characteristics that directly influence the development and aromatic concentration of the grapes. These are usually natural conditions specific to the vineyard location, such as its orientation, the presence of a forest or a mineral outcrop on the surface. In Champagne, a ‘clos’ is usually a walled-off portion of a vineyard identified by a winegrower for its natural potential. This artificial barrier creates a microclimate specific to this plot which will, over the years, develop its own aromatic identity. Given these specificities, one can better understand why many of the winegrowers who are lucky enough to own such plots of land decide to produce cuvées that are parcel-based and very often vintage wines.

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Dis, “Vin Secret”‘, Extra-Brut ($140)

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Dis, “Vin Secret”‘, Extra-Brut ($140)

• 70% Meunier, 25% Pinot Noir, 5% Chardonnay

• Harvested in 2018 plus small amounts of vins de réserve

• From 30 to 70-year-old vines

• 100% stainless steel aging

• 4 years sur-lattes

• Disgorged in June 2023 and dosed at 11.75 grams (the highest I’ve ever seen from Bedel)

Dis, “Vin Secret” Extra Brut showcases the delicate fruitiness of Pinot Meunier grown on heavier silts and clays then aged ‘sur latte’ to the point where the primary fruit is in perfect harmony with the wine’s autolytic expression. While frequently released as a 100% bottling of Meunier, this year Vincent added 25% Pinot Noir and 5% Chardonnay and dosed it with an unusually high percentage of sugar.

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Entre Ciel & Terre’, Harvest 2015, Extra-Brut ($105)

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Entre Ciel & Terre’, Harvest 2015, Extra-Brut ($105)

• 50% Pinot Noir, 35% Meunier, 15% Chardonnay

• 100% from 2015

• From 30 to 70-year-old vines

• 100% stainless steel aging

• 3 years sur lattes

• Disgorged in June 2021 and dosed at 4.20 grams

‘Between heaven and earth’ is a fine name for a biodynamic wine originating in vineyards planted on calcareous clay soils. It is aged 5 years ‘sur latte’ and bottled with a modest dosage, to show aromas of wildflowers, green olive and bright cranberry; upon opening, a deeper nose displays a complex layer of rosemary, white pepper and a touch of forest floor.

Bedel’s Vintage Champagne

No mumbo-jumbo wine lexicography here; vintage Champagne is made from the harvest of a single year. As it is generally only made in superior vintages, frequently only three to four times every decade, it may fairly be viewed as an indicator of quality.

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘L’Âme de la Terre’, 2008 Extra-Brut ($117)

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘L’Âme de la Terre’, 2008 Extra-Brut ($117)

• 50% Chardonnay, 30% Pinot Noir, 20% Meunier

• 2008 vintage

• From 30 to 60-year-old vines

• 65% stainless-steel and 35 % oak barrel aging

• 14 years sur-lattes

• Disgorged in June 2023 and dosed at 10.35 grams

L’Âme de la Terre is a vintage-dated champagne grown entirely on calcareous clay soils and fermented in a combination of enameled stainless-steel tanks and French oak barrels. It is aged ‘sur-latte’ for 14 years before disgorgement and finished with a serious dosage of 10.35 grams. The wine shows luscious ripe apple, and a bit of marzipan behind a mouthwatering minerality.

Notebook …

Champenois Radicalism: The Emergence of Vignerons and Micronégociants

First, a somewhat inconvenient truth: If asked what the term ‘négociant’ means, the honest answer is ‘nothing.’ Some négociant buy grapes, some mature wine, and some simply put their name on the label. Some, like Olivier Leflaive, dislike the term entirely: “I see myself as a winemaker, not a négociant, as I make the wine, from the beginning of vinification through to bottling.”

More than half of Burgundy is made by négociants whose average size is ten times that of the average domain. In Champagne, it is a different story; complicated local economics, long in thrall to massive companies, is shifting its prestige dynamics toward individual vignerons. The most earth-shattering paradigm shift in this approach is seen in the emergence of artisan styles in a region where uniformity has long been the key to success.

Into this swirl of radical rethinking comes the micronégociant. The name refers not only to their size (generally much smaller than the traditional négociant) but to the fact that many purchase grapes while continuing to farm them. Says Jean-Hervé Chiquet of Jacquesson, who farms 69 acres and purchases fruit from seven more: “We’re vignerons who buy a lot of grapes or we’re négociants who grow a lot of grapes. You decide.”

In Champagne, where a prime hectare (2.5 acres) of vineyard may cost over a million euros, few banks will lend a young grower the money to buy land, but a micronégociant can purchase barrels here and there—a typical entry route for newcomers who did not inherit an estate, or for those who want to extend a small family domain.

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

To be Champagne is to be an aristocrat. Your origins may be humble and your feet may be in the dirt; your hands are scarred from pruning and your back aches from moving barrels. But your head is always in the stars.

As such, the struggle to preserve its identity has been at the heart of Champagne’s self-confidence. Although the Champagne controlled designation of origin (AOC) wasn’t recognized until 1936, defense of the designation by its producers goes back much further. Since the first bubble burst in the first glass of sparkling wine in Hautvillers Abbey, producers in Champagne have maintained that their terroirs are unique to the region and any other wine that bears the name is a pretender to their effervescent throne.

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

The lauded wine writer Peter Liem expands the number of sub-regions from four to seven, dividing the Vallée de la Marne into the Grand Vallée and the Vallée de la Marne; adding the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay and combining the disparate zones between the heart of Champagne and Côte de Bar into a single sub-zone.

Courtesy of Wine Scholar Guild

Lying beyond even Liem’s overview is a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that compliment or contrast when final cuvées are created.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Épernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

… Yet another reason why this tiny slice of northern France, a mere 132 square miles, remains both elite and precious.

Three Primary Varieties and Four Heirloom Grapes

Champagne, with few exceptions, is a blended wine. Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Meunier are the trinity that form the bulk of these blends; a handful of heirloom grapes that have official government sanction in certain locations within the AOP.

Although they make up fewer than 0.3% of planted acres, with the dramatics being wrought by climate change, these other varieties may find a more prominent role in future blends:

Arbane is a late-ripening variety that succumbs easily to bad weather, and yet—under ideal conditions—produces a Champagne with remarkable finesse, offering nuanced notes of hawthorn blossom and carnation and as well as peach, apple and quince.

Petit Meslier is another milktoast variety, highly susceptible to disease and frost. But when it produces, it does so with both barrels, bringing a smoky quality to the wine that makes it identifiable, even when used in small quantities.

Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc, both white cousins to red Pinot Noir are low in acidity and somewhat easier to work with than Arbane or Meslier, although like Pinot Noir, Gris may be somewhat finicky. Both bring to blend their own magic; Gris offers a nutty quality to the finished wine and Pinot Gris adds punch and body.

- - -

Posted on 2024.10.01 in France, The Champagne Society | Read more...

Savoie Fare: Father & Son Team Jean-Noël and Thomas Blard Make Distinctive and Immediately Appealing Wines from Rare, Local Varieties in This Mountainous French Alpine Region 7-Bottle Sampler Pack $214

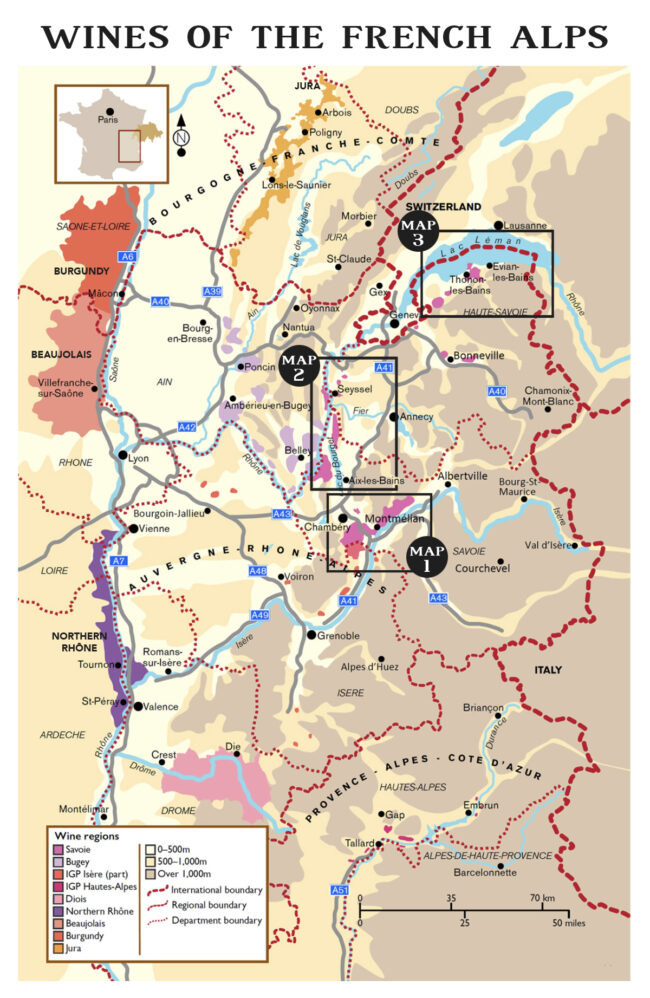

Italy is one giant vineyard, cuff to heel, but in France, wine regions are like fireflies in a midnight garden; they light up isolated corners. The brightest fireflies command most of the attention, of course, and as a result, the highest price points. But Savoie—in the far eastern part of France where the Alps spill over from Italy and Switzerland—is one of most remarkable of the glimmers.

The White Stuff: A Golden Opportunity

According to Wink Lorch, an avid skier and arguably Savoie’s most vocal champion, the development of the post-war ski industry represented a turning point for the region’s popularity: “This created new customers for its wines, of which very little get exported. Even so, up until the 1970s, there were hardly any vine-growers who lived solely from their vines.”

Reconquering the Slopes

Over the past twenty years, however, a new wave of independent vignerons has been boosted by organizations dedicated to preserving the singular grape varieties of the region, and Savoie has finally begun to come into its own.

Alpine wines have a crunchy sizzle and a cool sappiness unlike wine from anywhere else. Not only that, but the predominant grapes don’t show up on many other radars, so the unique textures commingle with a whole new flavor profile to surprise and delight the palate.

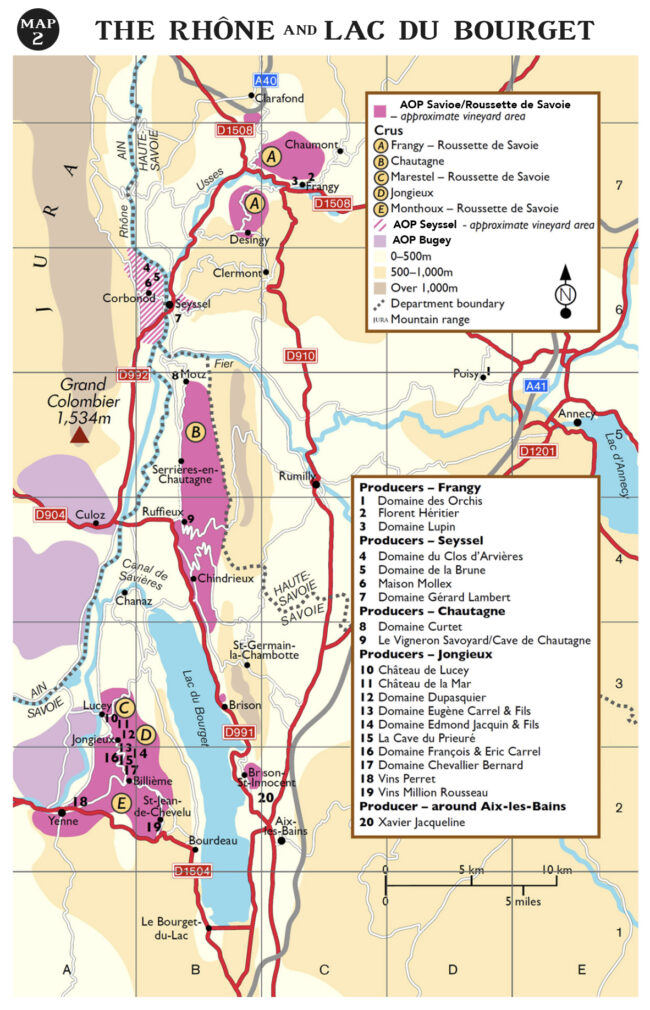

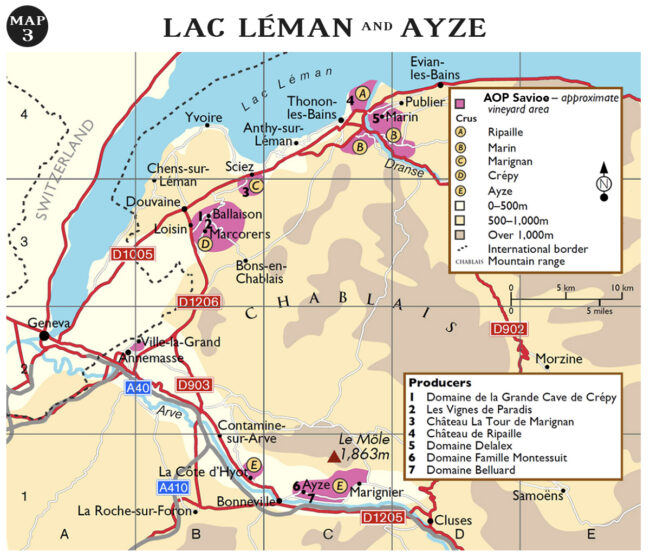

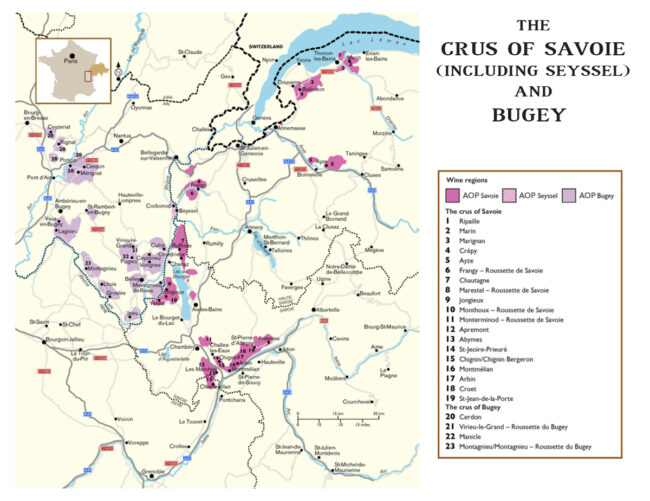

For the historically inclined, Savoie was the point where Hannibal crossed the Alps en route to Rome; for vinophiles, Savoie encompasses two main sub-appellations—Bugey, with 1250 acres of vines and Vin de Savoie, or simply Savoie AOP, which includes Roussette de Savoie and Roussette du Bugey. There are also 17 Vin de Savoies Crus and four Roussette de Savoie Crus, whose name may appear on labels. Most Savoie vineyards are planted on steep, south facing slopes, where favorable sunlight exposure and excellent drainage make for perfect ripening conditions despite the cold continental climate. The presence of lakes Bourget and Geneva, as well as the upper Rhône River, further moderate the climate. Most Vin de Savoie vineyards are found on limestone-based soils, which is adept at storing heat during the day and reflecting it back onto the vines at night.

Wines That Refresh Like Mountain Air

Metaphors linking wine to its place of origin are the stuff of poetry, but they’re also the foundation of terroir. Among the most common descriptors of high-altitude wine is ‘refreshing’ which is an offhand way of saying that they tend to be lower in alcohol and higher in acidity than valley wines. These acids are often the end result of the cool mountain air which they resemble, giving distinct, cleansing mineral characteristics to the wine with citrus and herbs rather than jammy fruit.

Managing Mountain Acidity While Keeping It Light

That said, it is sometimes a challenge for winemakers to reign in mountain-borne acid and to keep it from running away with the profile. Tart is acceptable—sour is not. Without delving into too much chemistry, the predominant acids found in wines are tartaric, malic, citric and succinic, and all but the last occur naturally in grapes—succinic acid is produced by yeast during fermentation. In areas where long hang-times for grape bunches to develop sugars and tame acidity are not possible in the mountains, and winemakers will occasionally resort to artificially manipulating the juice, the must, or as a last resort, the finished wine.

These are not wines we embrace at Elie’s, preferring those that display natural balance, favoring the expression of terroir over excessively extracted fruit with high sugar levels. Adjusting acid rather than preserving it defies one of winemaking’s oldest adages: ‘Good wine is made in the vineyard, not in the cellar.’

The wines of Savoie (even the reds) tend be light and somewhat playful on the palate, filled with alacrity and crackle and with correspondingly low alcohol levels to match an ethereal mountain finesse. Yet, we have found many wines of Blard & Fils that seek to take traditional Savoie varietals to the next level, busting through the clichéd ‘Ski & Raclette’ ceiling to create sophisticated wines suitable for the most refined tables.

Seven-Bottle Sampler Pack $214

The wines in this 7-Bottle Sampler Pack represent one of Savoie’s icons and iconoclasts, Thomas Blard, who has taken the management reins from his father Jean-Noël. They represent the wide array of native grapes and their associated flavor profiles that are typical of this hinterland of marvels.

Setting the (Appellation) AOP Scene: Savoie & Roussette de Savoie

Located in the foothills of the vast Alpine ranges of Switzerland and Italy, Savoie AOP grows grapes at altitudes between 800 and 1800 feet. Savoie’s 11,300 acres of scattered vineyards are responsible for less than 0.5% of the wine produced in France, and of the 3 millions of wine made in Savoie every year (compare this to Bordeaux’s 158 million), only about 8% of it is consumed outside the appellation. Although even the highest vineyards are at foothill-elevation, the region is distinctly alpine, with towering white-capped mountains and pristine lakes dominating the surrounding terrain: Mont Blanc, France’s tallest peak at 15,000 feet, has a Savoie zip code. The vineyards are adapted to this environment, growing occasionally on 80-degree slopes. Ranging from rocky subsoil to sand (sometimes in the same vineyard) the Savoie terroir supports 23 different grape varieties.

A large portion of western Savoie falls under the sub-appellation Roussette de Savoie. Encompassing four Cru communes—Frangy, Marestel, Monterminod and Monthoux—Roussette wines are dry and made from the Altesse grape, here is called ‘Roussette.’ The name is a reference to the reddish tint that the grape acquires before harvest.

In the past, Chardonnay made up to half the content in Roussette bottlings, but the practice was outlawed in 1999.

Domaine Blard et Fils

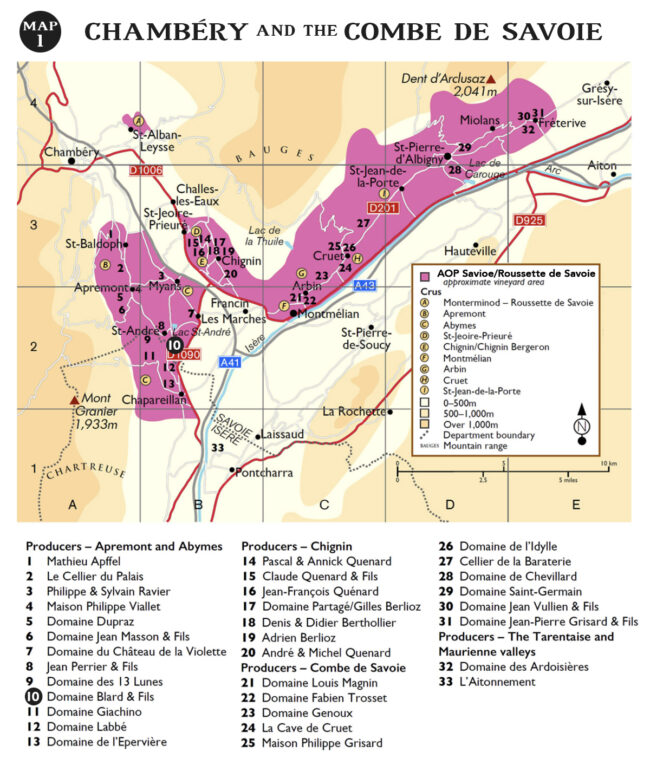

Abymes, Apremont, Arbin, Roussette de Savoie

Apremont is perhaps the best known white wine Cru in Savoie. Surrounding the tiny village of Apremont, just south of Chambéry, the vines make up one of the most southerly Crus in the department. Apremont wines are made predominantly from the local Jacquère grape and are typically light and dry with floral, mineral characters.

In part, Blard & Fils is hard at work changing preconceptions about this terroir.

Jean-Noël and Thomas Blard are a father/son team who has taken their family domain to new quality heights while moving steadily toward fully organic and natural viticulture. In the 1990’s, Jean-Noël became one of the first vignerons in the appellation to diversify into Pinot Noir, and was also eager to raise the quality bar on Jacquère and Mondeuse—the latter by aging in neutral oak for a minimum of two years. With 25 acres under Blard control, grassed over and fertilized naturally, the Blards use a technique known as ‘intercep’ to remove unwanted greenery before finishing the job by hand.

Jean-Noël and Thomas Blard, Domaine Blard & Fils

Five generations of Blard have snatched victory from the jaws of defeat: In 1248, the side of Mont Granier (one of the major formations of the Savoie’s Chartreuse Massif) collapsed, and a wave of boulders and scree crushed the landscape below, forever changing the soil structure. Apremont means ‘bitter mountain’ and Abymes means ‘ruin’ and as a result of the natural upheaval, it is today it is considered to be the best place in the Savoie (and by extension, all of France) to grow Jacquère.

Altesse: Her Highness’ s Balancing Act

Nowhere in the world does Altesse reign as regally as in Roussette de Savoie, an AOP which has adopted the grape’s nickname ‘Roussette’ as its own. Late to ripen, and turning pink near harvest, the variety produces small grapes with a tight-bunch structure. Its most significant success is as a stand-alone varietal (chiefly in Roussette de Savoie and Roussette du Bugey), but it is also permitted as a minor blending component in the Jacquère-predominant Vin de Savoie wines.