The Color of Change: From Off-Appellation to Second-Label Standouts, Bordeaux’s Elite Producers Turn to Dry Whites – Quietly Expanding the Region’s Identity Three 3-Bottle Dry White Samplers Sauternais $88 · Médoc $234 · Pessac-Léognan $131

Location, locution, libation: The three cardinal rules of real estate are thus rewritten when Bordeaux turns from red to white, and some back-story is required for a true appreciation of the change.

And along with the climate, that story is changing almost too quickly to follow.

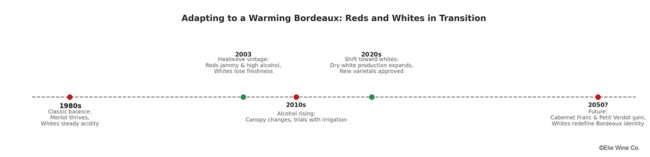

Twin drivers—weather and a market shift toward fresh, mineral-driven wines—happen to have aligned with Bordeaux’s efforts to reassert its white wine identity to heed the call of modern wine drinkers who seem less enamored with big, pricey, cellar-destined reds and more in fresher wines that can be enjoyed tonight. To further fuel this phenomenon, Bordeaux’s governing bodies are allowing the region more flexibility, including permitting experimentation with both heritage and non-traditional varieties. This has led some classified estates to ‘future-proof’ by increasing their plantings of white varieties, even at the expense of older, previously red-dominated vineyards.

Whereas this might seem logical in Pessac-Léognan and Graves, it’s increasingly the case in second-label and Right Bank châteaux.

This week, we peel back a multilayered curtain that formerly relegated most white Bordeaux to a postscript, and offer as packages a few examples of both first and second wines that will highlight how Sauvignon and Sémillon-driven wines from Bordeaux stand apart from those in the rest of the world.

Two thousand years of tradition and innovation have paid dividends in Bordeaux, and that sort of savoir-faire is color blind.

La Carte des Vins s’il vous plait!

Rewriting the Script: How Climate Change is Shaping Bordeaux’s White Wine Identity

Until fairly recently (with a handful of notable exceptions led by Sauternes) white wine from Bordeaux was often treated as an afterthought. Of Bordeaux’s 275,000 acres of vineyard, only about 10% are planted to white varietals, and the bulk of that winds up bottled under the often forgettable and generic ‘Bordeaux Blanc’ label.

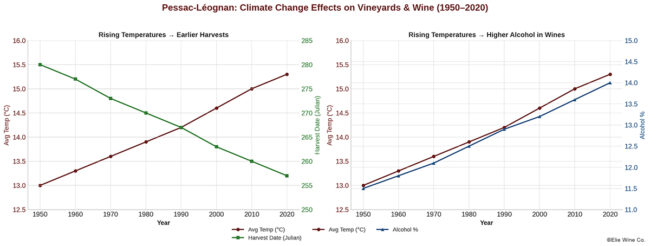

Enter climate change, an existential threat to an industry that is thousands of years old, and as vines may thrive in poor soils, innovation often arises from a crisis.

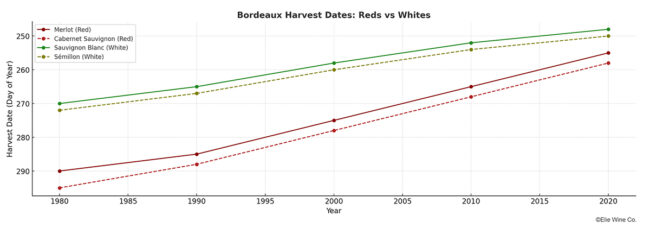

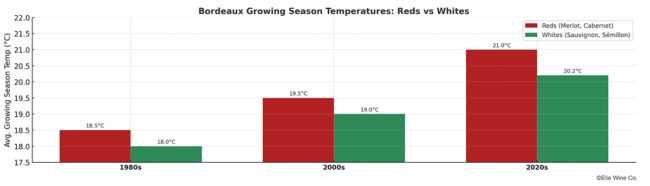

Bordeaux’s ocean-influenced climate has warmed significantly over recent decades and its primary workhorse grapes, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, in ripening earlier, have begun to develop higher sugar content (leading to more alcohol in the finished wine), sometimes at the expense of freshness and balance. Simultaneously, lighter, more lyrical wine profiles are the very qualities that modern consumers are looking for.

This alignment of stars, both in the heavens and on the shelves, works in the favor of Bordeaux’s white wine tradition, built around Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon, with Muscadelle and Sauvignon Gris rounding out the roster—varieties that ripen earlier than the reds and offer a trend-friendly counterbalance of acidity and aromatic freshness.

Climate Change and the Future of Bordeaux Wine

Whites from the Land of Sweets: Three-Bottle Sampler | $88

When it comes to Sauternes, the popular notion is that there is d’Yquem and then there is everyone else. This may be accurate in terms of pricing, but quality is a matter of taste. In fact, many other estates are often overlooked when consumers lock themselves into celebrity fawning, and there are several châteaux whose shift toward dry wines—survival mode though it may be—are creating outstanding products at outstanding price points.

This week’s dry white sampler package will open up the vista of Sauternes styles with which you may not be familiar, but can easily—and affordably—learn to love.

Bordeaux Blanc: The Dry Side of Sauternes

When the coffers begin to run dry, so do the wines. That could be a new motivational slogan and business model in Sauternes, home to the most celebrated sweet white wines in the world. Its reputation is built on low yields of botrytized grapes, and has always been a luxury at any table; these days, it faces a shrinking consumer demand for sweet wines (even the best) and top tier labels have seen a string of lackluster vintages—this, in a market where prime vintages such as the 100-point trio of 2001, 2007 and 2009 represented the lion’s share of sales.

Says Bérénice Lurton, who recently sold her majority stake in Château Climens; “Turning a profit from Sauternes can be an utterly demoralizing task.”

With the possible exception of Château d’Yquem, most estates cannot rely on their sweet wines to pay the bills without help, and in many cases, this involves turning toward the production of dry Sauternes.

Sauternes vintners don’t describe any specific climactic conditions preferable for parcels destined for sweet-versus-dry production, and this makes sense considering the château model, wherein estates harvest fruit from their contiguous properties rather than sourcing from multiple vineyards. As a result, all of these sites have the propensity to develop noble rot, leaving that question out of the equation when choosing dry parcels. Instead, vignerons might choose their dry wine plots based on varietal composition or vine age (typically setting aside the older vines for Sauternes). Commonly, the dry wine portions of the vineyard are decided upon before the growing season and rarely alter between vintages.

And now the irony: Although aggravated in recent years, the weather in Sauternes, as in the rest of Bordeaux, has been warming for nearly a century, today’s dessert wines were considerably drier and more suited as an accompaniment for the first course rather than the last; chefs considered Sauternes as an ideal accompaniment to salmon and turbot.

Even as late as the 1980’s, the top producers had not entirely secured their current reputation for creating France’s most iconic dessert wine. And so, the current return-to-the-future of dry wines in Sauternes, may be part of an ongoing cycle of climate adaptations and the ever-present hunt for consumer approval.

La Carte des Vins s’il vous plait!

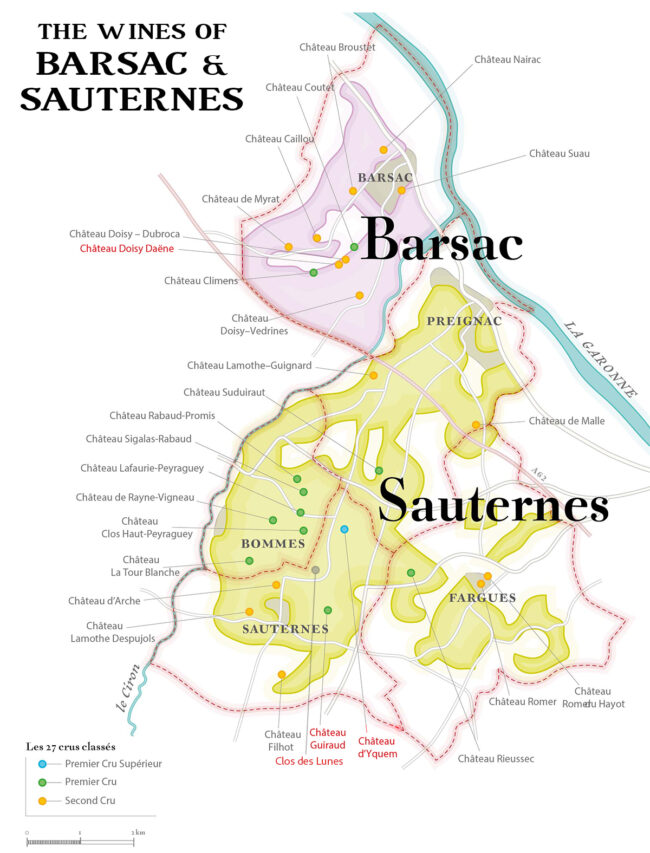

Château Doisy-Daëne

Barsac

Château Doisy-Daëne in Barsac (one of Sauternes’ five villages) claims to be the first classified growth to produce a dry wine, beginning in 1948:

“Sweet wines were doing very well. It originally seemed a shame to produce a dry Bordeaux in a classified estate,” explains Jean-Jacques Dubourdieu, vigneron at Château Doisy-Daëne says of his great-grandfather’s decision.

Located on the clay-limestone plateau atop Haut Barsac, Doisy-Daëne has depended on this geological unicorn to create three distinct top quality wines; Château Doisy Daëne, a sweet Sauternes, L’Extravagant de Doisy Daëne, (an extra sweet Sauternes produced only in select vintages), and Grand Vin Sec du Château Doisy Daëne—a dry Bordeaux Blanc from 100% Sauvignon blanc and aged 8 months in oak barrels of which 20% new.

The estate’s 45 acres of vineyards are planted with 86% Sémillon and 14% Sauvignon blanc.

1 Château Doisy-Daëne, 2022 Bordeaux Blanc ($35)

1 Château Doisy-Daëne, 2022 Bordeaux Blanc ($35)

Succulent and fresh, Doisy-Daëne’s ultra-affordable Sauvignon Blanc is an herbal blend of verbena, thyme, tarragon and oyster around juicy core of white peach, gooseberry, lemon peel and yellow plum; gracious and light, this is an ideal seafood accompaniment.

Château Guiraud

Sauternes

Talk about specificity: Château Guiraud states its location as being ‘between the church bell and the first vines of d’Yquem.’ Chances are, those vines are Sémillon, since that great estate is predominantly planted to this variety. Robert Peugeot and three winemakers—Olivier Bernard, Stephan Von Neipperg and Xavier Planty—purchased the estate in 2003.

And what a purchase! Guiraud is massive at 250 acres. The soil is 80% gravel and 20% gravel mixed with clay, and sub-soils composed mostly of sand. Varieties are broken down to 65% Sémillon and 35% Sauvignon Blanc. Harvests, in an effort to find grapes with ideal ripeness and noble rot, are done by hand, in six individual passes.

About 17 acres are reserved for ‘Le G de Guiraud’—the dry version—in which 80% of the three-week-long fermentation takes place in barrels previously used for their Premier Cru Classé Sauternes and 20% in stainless steel vats. Following this, the wine is aged in barrels for 7 months with stirring on the lees.

Guiraud was certified organic wine in 2011, but had been practicing it since 1996—the first of the 1855 Premiers Crus to do so.

2 Château Guiraud ‘Le G de Guiraud’, 2023 Bordeaux Blanc Sec ($25)

2 Château Guiraud ‘Le G de Guiraud’, 2023 Bordeaux Blanc Sec ($25)

An even blend of Sémillon and Sauvignon Blanc, aged seven months in the oak barrels that produced the previous year’s Premier Cru, the wine is expressive and complex showing Meyer lemon, mint leaves, mandarin orange and a lot of minerality in the finish.

Clos des Lunes

Sauternes

When Olivier Bernard, (from an old Cognac-producing family) bought the Domaine de Chevalier in 1983, the estate that was ranked among the Crus Classés for both red and white wine in the Classification of Graves of 1953 and 1959. In 2011 he embarked upon a shocking project: ‘Clos des Lunes,’ in which he wanted to produce the best dry white wine in Bordeaux by taking grapes destined to craft perhaps the most desirable dessert wine in the world (Sauternes) and create instead a dry white wine which would sell for under $30.

The 110-acre estate is planted to 70% Sémillon and 30% Sauvignon Blanc. The vines are old-ish, with an average age of 30 years. Lune d’Argent is the heart of Clos des Lunes’ production, and the estate refers to this wine as the ‘La Grande Cuvée.’

All work done is organic, with the goal of moving to a complete, self-sustaining vineyard. Bernard says, “In Sauternes, respect for nature is inextricably linked with the region’s viticultural heritage. The development of botrytis can only occur in a vineyard where the environment is protected. Reconversion to organic agriculture is relatively straightforward. A traditional, natural, manual approach in the vineyard and winery has been passed on from generation to generation.”

3 Clos des Lunes ‘Lune d’Argent’, 2023 Bordeaux Blanc ($28)

3 Clos des Lunes ‘Lune d’Argent’, 2023 Bordeaux Blanc ($28)

Tart and quite tropical with crushed citrus, pineapple, and white flower notes. With a touch of French oak, the Sémillon is dense and rich, the Sauvignon Blanc refined and precise. This cuvée is vinified dry, but promises to convey all the magic of Sauternes.

Château d’Yquem

Sauternes

As the only Sauternes to hold the Premier Cru Supérieur designation, d’Yquem is the undisputable top-tier of Sauternes, and so much press has it received over the centuries that it is difficult to avoid repetition. In short, Château d’Yquem is a global icon for dessert wines.

Part of that reputation is due to d’Yquem’s location; perched on a hilltop at the highest point in the appellation, its unique microclimate allows for winds from the east to move through the vineyard, helping to remove excessive moisture late in the growing season as the noble rot sets in. Botrytis, of course, is the key element in sweet Sauternes, from the lowliest to the mightiest. This fungus, given ideal conditions, shrivels grapes on the vine, concentrating their sugars and acids and creating the myriad flavors that in d’Yquem, are magnified.

Although the estate owns three hundred acres, only a portion are used in any given season. It is this somewhat obsessive-compulsive attention to detail that is the second factor that makes Château d’Yquem, even in its own appellation. Harvesting is carefully timed, and on average six passes through the vineyard are undertaken each year, where only botrytized grapes are selected. Yields are restricted to about a quarter of those allowed by AOP rules. Once pressed, the grapes are pressed again, and then a third time before being transferred to oak barrels for maturation over a period of about three years.

Château d’Yquem’s terroir is not particularly unique—a combination of clay, gravel, and sand over a bed of deep limestone soil. The clay varies, depending on the parcel. Interestingly, though, one can even find some of the same blue clay that makes up the soil in another Bordeaux superlative, Château Pétrus.

Château d’Yquem ‘Y’, 2022 Bordeaux Blanc ($270)

Château d’Yquem ‘Y’, 2022 Bordeaux Blanc ($270)

Roughly pronounced ‘ee-grek,’ d’Yquem’s has been producing a dry white, ‘Y’, since 1959, using vines and grapes chosen prior to harvest. While one bunch of Sauvignon Blanc may be designated for ‘Y’, the remaining bunch can be used for first-label d’Yquem if the necessary amount of noble rot develops.

It is produced in limited quantities (fewer than 1000 cases), and only in select vintages.

2022 was a ‘Y’ year—a cool, dry winter preceded a sweltering summer, ensuring that the grapes reached full phenolic ripeness. The dry conditions, while not ideal for botrytis, did, manage to keep other diseases at bay. Composed of 60% Sauvignon Blanc and 40% Sémillon, the 2022 Y has 6 grams per liter of residual sugar. The dry steeliness of Sauvignon Blanc couples with the richly honeyed qualities of Sémillon, and show notes of sliced apple, pineapple and lychee.

Bordeaux Blanc: When Great Vineyards Go Off-Label

As alluded to previously, climate change has forced most wine estates in Europe into some sort of self re-evaluation. In many cases, the higher sugar content of grapes in warmer seasons equates to more alcohol in the final wine, which bucks the trend in modern consumer tastes.

“The market is moving towards more drinkable wines,” says Helen Durand, the owner of Domaine du Trapadi in the Rasteau AOP. “That translates to a preference for whites, which are often more acid-driven, lower in alcohol, and generally fresher than the international style of red wine that once reigned.”

And nowhere did that ‘international style’ reign with a stronger hand than in Bordeaux. Between 2015 to today, exports of white Bordeaux to the U.S. have grown by over one-third and almost doubled in value.

Growth could be even stronger, according to Mary Gorman-McAdams, a Master of Wine currently writing a book about white Bordeaux for the Académie du Vin’s Classic Wine Library: “There are probably about 100 producers making white wine in the region at the moment, but those are simply labeled AOC Bordeaux. Producers have really exciting whites, but their importer partners aren’t bringing them in. It’s a Catch-22—Bordeaux gets slighted for not being innovative, but then those partners refuse to take on these forward-looking white wines because ‘that’s not Bordeaux.’”

We’re hoping that these selections convince you otherwise.

La Carte des Vins s’il vous plait!

Château Lynch Bages

Pauillac

Amid the fanfare and the brilliant marketing (Jean-Michel Cazes sent a bottle of 1975 Lynch-Bages into outer space aboard the space shuttle Discovery), Fifth Growth Château Lynch Bages is worth the hype. Under the tireless campaigning and quality-improvement of the Cazes family, who have owned the property since 1934, the estate has expanded to over 250 acres to the south and southwest of Pauillac.

Improvements to both soil and technique have been a hallmark of the Cazes approach; a massive renovation and modernization of the wine cellar took place in 2017, and cutting-edge vineyard management now includes satellite imaging to survey the vineyard and conducting soil surveys to ensure the vines reach their full potential.

Part of this potential lies in white wine production, with 15 acres devoted to it. Planted to 53% Sauvignon Blanc, 32% Sémillon and 15% Muscadelle, Lynch Bages Blanc made its debut in 1990.

1 Château Lynch Bages ‘Blanc de Lynch-Bages’, 2022 Bordeaux Blanc ($108)

1 Château Lynch Bages ‘Blanc de Lynch-Bages’, 2022 Bordeaux Blanc ($108)

67% Sauvignon Blanc, 22% Sémillon and 11% Muscadelle; the grapes undergo a mix of pressings, both with and without stems, followed by fermentation in oak for two-thirds of the crop and in vat for the rest, then aging for six months on lees. The wine’s color shows brilliant straw tones and flavors run from passion fruit to grapefruit, lemon curd and white peach with hints of honeysuckle, lime blossom and a finish of dusty chalk.

Château du Tertre

Margaux

In French, ‘tertre’ means ‘hillock,’ which is perfectly describes where the vineyards of Château du Tertre are located. With a history dating to 1143, du Tertre is one of the oldest properties on the Left Bank. At 134 acres, it is the same size today as it was at the time of the 1855 Classification of the Médoc, making it a rarity.

Tertre soil is mostly gravel with some sand pockets on two gently sloping hills where cooler ambient temperature has been credited with the wine’s much-vaunted freshness, since the cooler ambient temperature adds more zing to the wines. The single bloc is planted to 43% Cabernet Sauvignon, 33% Merlot, 19% Cabernet Franc and 5% Petit Verdot, separated from their sister property, Château Giscours, only by a small stream.

Beginning in 2014, the estate began to produce a white wine based on the peculiarity of terrain on the estate, which includes a large pine forest. Proximate to this natural feature of the landscape are varieties unusual for Margaux, including Chardonnay, Viognier and small amount of Gros Manseng.

2 Château du Tertre ‘Tertre Blanc’, 2021 VDF ‘Bordeaux-Margaux’ ($39)

2 Château du Tertre ‘Tertre Blanc’, 2021 VDF ‘Bordeaux-Margaux’ ($39)

38% Gros Manseng, 25% Viognier, 25% Sauvignon Blanc and 12% Chardonnay: Succulent and full-bodied with lots of exotic fruit—guavas, green mangoes and gooseberries wrapped in subtle creaminess. Bone-dry with a quick saline tang at the end.

Château Brane Cantenac

Margaux

One of fifteen Deuxièmes Crus (Second Growths) in the original Bordeaux Wine Official Classification of 1855, the estate had been producing one of the Médoc’s most highly regarded wines long before that. For four consecutive generations, the Lurton family has been at the helm, with Henri Lurton as the current proprietor. He says, “The exceptional terroir of Château Brane-Cantenac is made of deep quaternary-era gravels. Each plot has been carefully studied to plant the most suitable grape-variety, the one which will express itself the best on it. Along with my team we strive to reveal each plot’s potential by working in a plot by plot and intra-plot approach: The ‘Burgundy way.'”

Brane-Cantenac’s terroir can be subdivided into several parcels; the first and most valued is planted in a large sweep of gravel in front of the château at the top of the Margaux-Cantenac plateau, providing radiant heat to the vines as well as excellent drainage. The second section is situated behind the château, where the gravel is intermixed with sand. La Verdotte is a 25-acre vineyard planted 35 years ago with 55% Cabernet Sauvignon, 40% Merlot, 4.5% Cabernet Franc, and 0.5% Carmenère. A fourth vineyard called Notton is a 13-hectare plot of coarse gravel over clay, and more distant from Brane-Cantenac than the other vines.

A newbie to white wine, the estate has a scant ten acres in the cooler Haut Médoc planted to 80% Sauvignon Blanc and 20% Sémillon. 2019 was the first vintage that Brane-Cantenac Blanc was produced.

3 Château Brane Cantenac ‘Brane-Cantenac Blanc’, 2021 Bordeaux Blanc ($87)

3 Château Brane Cantenac ‘Brane-Cantenac Blanc’, 2021 Bordeaux Blanc ($87)

70% Sauvignon Blanc and 30% Sémillon; the wine offers an aromatic opening of pineapple, mango and grapefruit, which leads into a honeyed mid-palate filled with gooseberry, lime zest and a touch of fresh thyme and coriander.

Château Margaux

Margaux

Margaux has drawn praise from aficionados as diverse as Suzi Quatro (“I’m a bit of a wine snob and like a glass of Château Margaux ’82 to unwind) and Ernest Hemingway (“I drank a bottle of wine for company, Château Margaux. It was good company” – ‘The Sun Also Rises’), while Thomas Jefferson waxed philosophically about vintage 1784.

In part that is because Château Margaux is the most user-friendly of the five classified Premier Cru Classé wines: André Lurton, who grew up in a Margaux wine family in the 1930s, sums it up like this: “Wines here were never about extraction or power. They were all about finesse. That’s what we looked for and admired in a wine.”

Château Margaux covers about 650 acres, of which 210 acres are entitled to the Margaux AOP declaration. 200 acres are planted to 75% Cabernet Sauvignon, 20% Merlot, with 2% Cabernet Franc and Petit Verdot.

30 acres are dedicated to Sauvignon Blanc to make the dry white Pavillon Blanc.

Château Margaux ‘Pavillon Blanc’, 2018 Bordeaux ($351)

Château Margaux ‘Pavillon Blanc’, 2018 Bordeaux ($351)

100% Sauvignon Blanc. Château Margaux is old hat at producing white wine; this label came into being in 1920, and was called Château Margaux Vin de Sauvignon prior to that. These days, it is produced in very limited quantities and crafted in the new ultra-modern winery designed by architect Norman Foster. The wine shows an electric blend of kiwifruit, passionfruit and mineral acidity with a long, mineral finish.

La Carte des Vins s’il vous plait!

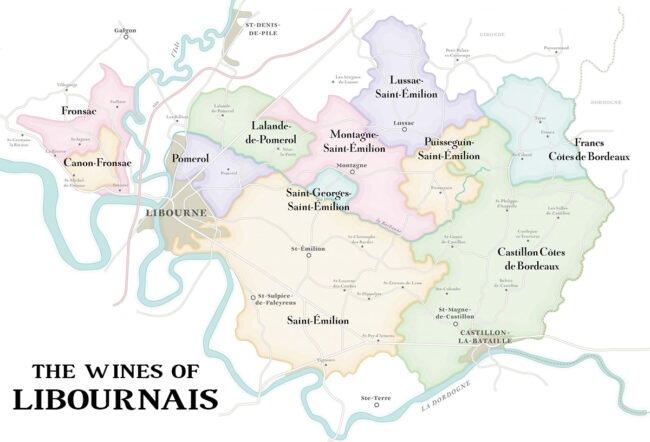

Château Cheval Blanc

Saint-Émilion

The fact that the estate is located in the northwest portion of Saint-Émilion on the Pomerol border explains some of the renowned voluptuous quality of Cheval Blanc; it is rightly claimed that the ‘White Horse’ showcases the best attributes of both appellations.

In 2015, Cheval Blanc started producing a dry white wine called ‘Le Petit Cheval Bordeaux Blanc.’ The initial vintages were produced using 100% Sauvignon Blanc. Starting with the 2018 vintage, the wine has been made using a blend representing the vineyard makeup—80% Sauvignon Blanc and 20% Sémillon—planted on three-and-a-half acres just across the road from Cheval Blanc in vineyards previously used by La Tour du Pin.

Château Cheval Blanc ‘Le Petit Cheval Blanc’, 2021 Bordeaux Blanc ($207)

Château Cheval Blanc ‘Le Petit Cheval Blanc’, 2021 Bordeaux Blanc ($207)

83% Sauvignon and 17% Sémillon. At the end of pressing, the lightly settled grape musts were fermented in demi-muids, foudres and wooden vats.

“After vinification, the rhythm of stirring, initially on a daily basis, decreases,” according to the production crew.

The wine is a finely-balanced mix of acidity and fleshiness, showing apricot and white pear nuanced with fennel.

Château Vieux Taillefer

Saint-Émilion

This postage-stamp of an estate, perched on the bank of the Dordogne river, is only 12 acres in size. It’s planted mostly to Merlot with a little Cabernet Franc and a handful of white varietals planted in the 1950s.

Philippe Cohen, originally from Paris, lived in Saint‐Émilion for 10 years working as a négociant, while his wife Catherine studied oenology. They were able to purchase Vieux Taillefer in 2006, fulfilling a lifelong dream of producing world-class Bordeaux.

And yet, the couple has approached the Château with a Burgundian sensibility. All fruit is hand-harvested and undergoes a careful sorting before it is vinified in concrete tanks. The work is 100% organic, and there is no fining or filtration, and the Cohens are quick to point out that they employ no consultants at Vieux Taillefer.

They produce a white wine from 75-year-old vines, a blend of Sauvignon Blanc, with some Semillon, Sauvignon Gris, Merlot Blanc, and Chasselas.

“More than 200 years ago, the majority of the production in Saint‐Émilion was white,” Catherine points out. “This wine pays homage to that history.”

Château Vieux Taillefer ‘Blanc du Château Vieux Taillefer’, 2018 VdF ‘Bordeaux-Saint Émilion’ ($74)

Château Vieux Taillefer ‘Blanc du Château Vieux Taillefer’, 2018 VdF ‘Bordeaux-Saint Émilion’ ($74)

Says Philippe Cohen: “This wine is blend of five grape varieties, the majority of which is white Merlot, a somewhat unique grape. It comes from a plot located in Saint-Christophe des Bardes, on a limestone soil with starfish, in the heart of Saint-Émilion. These very old vines are today the only white Merlot vines existing in the era of the appellation.”

The grapes are vinified and aged in new, very lightly toasted 300-liter cigar-shaped wooden barrels from central France. It shows honey, lemon, green apple and lightly toasted almonds over a gunflint core.

Clos du Milieu

Castillon-Côtes de Bordeaux

The Clos du Milieu is an offshoot of the famed Château Angelus, formerly a Premier Grand Cru Classé A in Saint-Émilion. Made entirely from vines under the management of the mother estate, the two cuvées, one red and one white, are intended to widen the Angelus range while promoting the Castillon-Côtes de Bordeaux appellation. Both bottlings are produced at Angelus’ Chai Carillon, but in a dedicated cellar.

Clos du Milieu Rouge is sourced from a single plot of Merlot bordered by hedgerows and located a few miles from Saint-Émilion, where deep clay-limestone soils on the upper slope lend tension and density to the wine that may at times rival the vineyards of Saint-Émilion at a considerably more relaxed price-point.

Blanc du Milieu originates in a four-acre plot of Sémillon and Sauvignon Blanc grape varieties situated in the commune of Castillon-la-Bataille, where the soil is clay and the soft, porous limestone known as ‘tuffeau.’

Clos du Milieu ‘Blanc du Milieu’, 2022 IGP Atlantique Blanc ($49)

Clos du Milieu ‘Blanc du Milieu’, 2022 IGP Atlantique Blanc ($49)

60% Sémillon and 40% Sauvignon Blanc, the grapes for this cuvée were direct-pressed and cold-settled; fermentation occurred in a combination of new barrels, stainless steel vats and concrete eggs. The aging lasts 18 months on fine lees with bâtonnage in new barrels and concrete eggs. The wine shows apricot and grapefruit on the nose, with a palate revealing subtle oak, roasted hazelnuts, stone fruit and a nettle-like herbalness.

Second Wines: Three-Bottle Sampler | $131

Rather than shedding tears, Bordeaux adds tiers—and classification is what Bordeaux is all about. While the Grand Vin is expected to be any château’s A-game, with technological advancements and an increasingly warm climate, the price of these top-shelf wines has risen with the temperature, and quality is ensured by an ever more rigorous selection of grapes on the sorting table.

Second wines—a tradition begun by Château Margaux in the 17th century—were the logical place to place grapes deemed unfit for inclusion in the Grand Vin. And since the terroir in which they were grown was often similar, and occasionally identical to the first wines (and generally made by the same vigneron), it stands to reason that the great estates would release these ‘little brother wines’ under some version of their famous name.

When an estate famed for red wines releases a white, it may not always be the result of substandard fruit—just fruit of a different color. That is certainly the case in this three-bottle sampler, where the wines have been treated with the same circumspection as the reds, and are often produced in response to consumer demands.

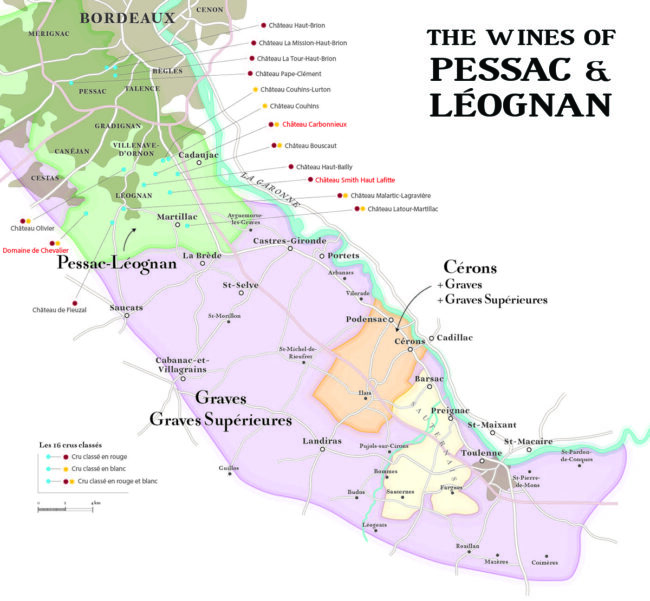

Pessac-Léognan Blanc: Second Acts, First Class

In 1987, a long-standing wrong was righted: The villages of Pessac and Léognan were singled out from the greater Graves region and given their own appellation. This move acknowledged that the wines of the newly-formed Pessac-Léognan were unique from surrounding villages in both depth and focus. Among the estates able to claim the new appellation title was the Premier Cru Château Haut-Brion.

Most of the area remains staunchly red—among the 4000 acres of Pessac-Léognan vineyard, more than 75% are planted to Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. It is the remainder that we will focus our attention upon: Unlike the famous sweet white wines from nearby Sauternes, Pessac-Léognan whites are generally crisp, dry and mineral-filled, with citrus notes, often with rich character notes added through oak aging and capable of improving for up to a decade. They are made predominantly from Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon, a duo that thrives in the sandier soils of the appellation and results in some of the most stunning examples of this blend that can be found.

La Carte des Vins s’il vous plait!

Château Smith Haut Lafitte

Pessac-Léognan

Rated as a red wine ‘Grand Cru Classé’ in the 1959 Classification of Graves, the château sits on a low hill of pebbles and sand deposited by the Garonne River, offering grape vines not only superb drainage, but also reflected sunshine to lengthen the day’s ripening period. The estate, of course, is not to be confused with Château Lafite Rothschild (the Pauillac superstar) with which it has no connection, but both were named for their elevated physical status—‘la fite’ is an ancient dialectical word for hill.

The château is owned and managed by Daniel Cathiard and Florence Cathiard, who purchased the estate in 1990 from the well-known Bordeaux négociant and importer Louis Eschenauer. The attraction, according to Daniel, was that Smith Haut Lafitte was one of the few Bordeaux vineyards producing both red and white wines.

In the production of Sauvignon Blanc-dominated white blends, Smith Haut Lafitte is known for whole-berry fermentation using a pneumatic press; there is no skin contact or malolactic allowed and vinification takes place in French oak barrels, where the wine is aged on their fine lees for a year.

1 Château Smith Haut Lafitte ‘Le Petit Haut Lafitte’, 2022 Pessac-Léognan Blanc ($58)

1 Château Smith Haut Lafitte ‘Le Petit Haut Lafitte’, 2022 Pessac-Léognan Blanc ($58)

80% Sauvignon and 20% Sémillon with a concentrated bouquet melon, honeyed citrus and chamomile; the wine is full-bodied mid-palate but retains a crisp and lyrical intensity all the way to a saline finish.

Domaine de Chevalier

Pessac-Léognan

Grapes may be the stock and trade of Pessac-Léognan, but as a land mass, it is mostly forest. Carved into a clearing in that forest, Domaine de Chevalier has been a mainstay of wine production in the region for hundreds of years. So much do the trees influence the wines that one of the first things Olivier Bernard did when he took over the estate (at the age of 23) in 1983 was removing the sheltering belt that surrounded those acres most susceptible to frost.

At the time, the estate had only 44 acres of vines. Among Bernard’s other early decisions was to retain the winemaking team and enlarge the holding. In 1985, he purchased additional plots from neighboring vineyards; next, he began a long-term replanting program lasting from 1988 to 1995, including in these 17 acres of Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon.

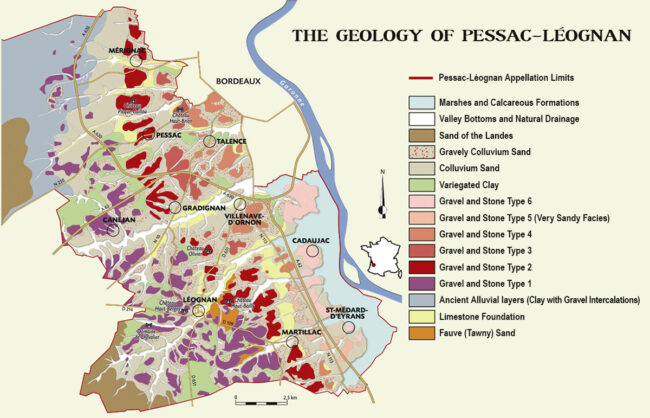

Today, he is joined in daily operations by his two sons Adrien and Hugo. With 65 acres under vine, divisible into 90 individual plots, the potent Pessac-Léognan terroir is built around gravel with black sand over clay and hardpan soil. There are gentle slopes and elevations throughout the parcel which rise to around 200 feet, relatively high for Bordeaux.

2 Domaine de Chevalier ‘L’Esprit de Chevalier’, 2022 Pessac-Léognan Blanc ($44)

2 Domaine de Chevalier ‘L’Esprit de Chevalier’, 2022 Pessac-Léognan Blanc ($44)

75% Sauvignon Blanc and 25% Sémillon with a full 18 months of barrel aging; the wine is silky and layered with citrus oil, gooseberries, Key Lime pie and a crisp acidity that turns stony on the finish.

Château Carbonnieux

Pessac-Léognan

In order to keep a healthy vineyard, Château Carbonnieux replants at least one or two plots of vines each year, although it will be many years before they produce fruit suitable for the Carbonnieux label. As such, the younger fruit is bottled under the Tour Léognan name.

Carbonnieux is an estate with which even a casual wine drinker is probably familiar. With more than 420 acres under vine, it is easily the largest vineyard in Pessac-Léognan, and one of the largest in Bordeaux. Its wines are widely available in the United States—especially the whites, since the acreage is evenly divided between red and white; 65% Sauvignon Blanc and 35% Sémillon.

3 Château Tour Léognan, 2022 Pessac-Léognan Blanc ($29)

3 Château Tour Léognan, 2022 Pessac-Léognan Blanc ($29)

65% Sauvignon Blanc and 35% Sémillon, with a light aging in French oak to add some spice and weight. A classic white Bordeaux with a mélange of gooseberry, dried mango, white flowers with crushed stone and a citrus lift on the finish.

Notebook …

The Originality of Pessac-Léognan Lies in Its Origin

That the area now specified as Pessac-Léognan is capable of producing world-class wines has been noted for centuries. The terroir is characterized by deposits of pebbles and gravel that has accumulated via the Garonne River for nearly two million years. The climate is regulated to the east by the river, which mitigates frost, and to the west by the forest, which protects vineyards from the prevailing winds and keeps the soil moist.

The key features of the appellation include a landscape of low rises that are sufficiently sloping to ensure good drainage, further facilitated by a network of small streams that act as natural drains feeding into the Garonne River; soils consisting of river gravel up to 25 feet deep are set on Tertiary limestone subsoil, both left behind by the river as it changed course during the Quaternary Era. These stones reflect the sun’s radiation, increasing the vines’ sun exposure and accelerating the ripening of the grapes—a combination of factors that represents Pessac-Léognan’s inimitable, inalienable heritage.

Tipping the Scales: Warm Summers and Wet Winters Boost Pessac-Léognan- For Now

Grappling with the pluses and minuses of climate change is a double serving of concern on the plate of every wine region on the planet; Pessac-Léognan is no exception.

First, what we all know to be true: Weather drives wine quality and taste. Temperature and precipitation occurring throughout the year—from bud break, while the grapes are growing and maturing, during harvesting, and even overwintering dormant vines—each play a role. The same vineyard can produce different quality levels in different years despite those wines coming from grapes grown on the same vines, on the same land, and being produced by the same methods.

With climate change upending many of the most predictable weather patterns (even among an otherwise random set of circumstances), a study done by Andrew Wood of the University of Oxford’s Department of Biology paired high-resolution climate data with annual wine critic scores from the Bordeaux wine region in southwest France from 1950 to 2020, and concluded that, “The trend, whether driven by the preferences of wine critics or the general population, is toward stronger wines that age for longer and give you richer, more intense flavor, higher sweetness, and lower acidity. And with climate change generally, we are seeing a trend across the world that with greater warming, wines are getting stronger.”

He adds: “With the predicted climates of the future, given that we are more likely to see these patterns of warmer weather and less rainfall during the summer and more rainfall during the winter, wines are likely to continue to get better. However, there is a tipping point; once water becomes more limited, if plants don’t have enough, they eventually fail. And when they fail, you lose everything.”

Pessac-Léognan’s ability to adapt and take advantage of this natural phenomenon is largely dependent on the commune in question, since each enjoys varying degrees of temperature modulation, allowing for differences in the levels of ripeness, alcohol, and picking dates. For example, Talence is warmer and there, the vineyards are picked earlier than Pessac, while Martillac harvests after Léognan. Overall, however, Pessac-Léognan is becoming increasingly warmer; 2022 saw the earliest start date for harvesting ever. 2022 was also the first vintage where some vintners requested and were able to irrigate select vines in various parcels due to the parching heat. Alice Leuret, Commercial director at Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion, indicates that irrigation permits required a mountain of paperwork, and at her estate, was restricted to five acres of young vines.

- - -

Posted on 2025.08.23 in France, Wine-Aid Packages

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Aligote, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Cinsault, Clairette, Corvina, Counoise, Dolcetto, Erbamat, Ferrol, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Gamay, Garnacha, Garnacha Tintorera, Gewurztraminer, Graciano, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malbec, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marcelan, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montònega, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscat, Natural, Niellucciu, Parellada, Patrimonio, Pedro Ximénez, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Pouilly Fuisse, Pouilly Loche, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Riesling, Rondinella, Rose, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sagrantino, Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Sciacarellu, Semillon, Serine, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Search