From Rock to Wine: Six Domaines Showcase Alsace Grand Crus’ Singularity of Character + Pinot Noir Is Taking Root in Alsace

As a gold medal represents the highest award that an Olympic athlete can win, in the wine world, Grand Cru is the highest designation to which a plot of land can aspire. If you are a lover of French wine (a rhetorical point since you are reading these words), it is no doubt a term that is both mysterious and sacred, as various pieces of earth have been considered in religious tradition from time immemorial; Kashi Viswanathan in India, Mecca in Arabia and Lourdes in France. Although not imbued with supernatural powers of healing, Grand Cru vineyards are saturated in terroir that is considered the ne plus ultra of any wider appellation.

At least, that’s the theory. In our continued exploration of Alsace this week, we find that Grand Cru status has an additional determining factor: Politics. This is not to suggest that these are not the finest wines that Alsace can produce, only that it may not be a guarantee of it, at least compared to Burgundy. Alsace has enormous geological diversity within a fairly constrained area, and each Grand Cru may rightly claim its own unique identity rather than an absolute commitment to rules that would ensure top quality.

And yet, an equal number of vignerons within a designated Grand Cru feel that the existent rules are too harsh.

Regarding this status, Hubert Trimbach, from his domain’s famous address in Ribeauvillé, once said about the Crus, “We are opposed! There is not enough discipline; yields are too high; quality is questionable; prices are ridiculous and criminal … This is a political time-bomb. No, no and no.”

This is a debate that you can moderate yourself, and fortunately, at a reasonable cost. Unlike Burgundy’s Grand Crus, which will usually set you back three figures, even the most prestigious Alsatian Grand Crus are generally around a hundred dollars and most are considerably less than that, as this week’s selection will prove.

The Grand Crus: Singularity of Character

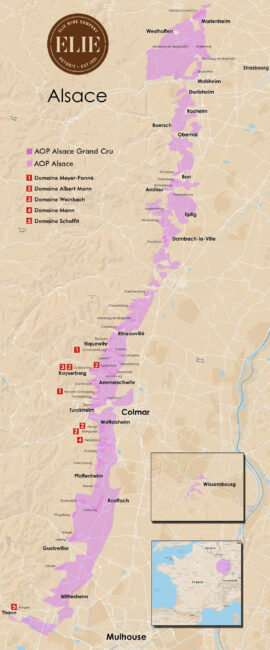

As viewed by an Alsace outsider, who may be able to instantly distinguish between an Echézeaux and a Chambertin, the problem with learning Alsace Grand Crus that are just so damn many of them. Beginning with the Schlossberg of Kaysersberg, the classification first peeked out from under the bed in 1975. A list of 24 new Grand Crus was added in 1983, followed by a further 25 in 1992. Ultimately, Kaefferkopf was added in 2007 to make a total of 51 Alsace Grand Crus.

Combined, they equal about 5.5% of the total vineyard area in Alsace, whereas in Burgundy, Grand Cru appellations account for less than 1%.

And once you’ve digested the nuts and bolts of Alsace Grand Crus, you can start in on the next course: Alsace Premier Crus. At first pass, you might think this is easy since there are none. But to date, 160 applications have been accepted by the INAO, and these are currently undergoing the rigorous approval process.

In fact, the whole hierarchy system in Alsace may soon see a profound change: Proposed is a new system wherein wines with a complementary denomination would be removed from the regional category and upgraded to a new level similar to Burgundy ‘Villages’ wines. They would be recognized as independent AOPs with specific production rules—‘cahier des charges’—and some high-quality lieux-dits that have shown consistency would be gathered into a new Premier Cru (1er Cru) category, with specific production rules as well.

The irony is that the proposed 1ers Crus vineyards will be delimited in a stricter way than the Grand Crus were, and there is a danger that some will out-perform the lesser Grand Crus.

As it is now, however, Grand Cru will remain as the sole representation at the top tier in Alsace’s exclusivity pyramid, but in the mind of Jean Hugel (of the family-run domain in Riquewihr): “There should have been 20 Grand Crus right from the beginning, and the rest should have been Premier Cru.”

Sugar: The Word That Cannot Speak Its Name

In Alsace, sugar has bedeviled winemakers and consumers for eons, although new regulations might be a little sugar to help the medicine go down.

According to Marc Hugel (Hugel & Fils): “When I first started in the trade 35 years ago, most of our wines contained three grams of sugar per liter or less. Now, most have more. I think there is correlation between our move toward sweet wines and low prices.”

Although dry wines is the purported goal of winemakers to meet a demand for food wine, warmer weather patterns have pushed ripeness, forcing producers to leave residual sugar to keep alcohol levels in check. Extra sugar can also hide; four grams per liter can seem bone dry with high enough acid levels. Another factor is that as wine ages, it tastes less sweet on the palate, a phenomenon that even Marc Hugel can’t explain. “Sometimes I leave residual sugar to keep alcohol moderate, but upon release six or seven years later, it tastes dry.”

The Grand Crus were defined at a time when getting to ripeness was problematic, so they are generally the sites that achieve greatest ripeness, often south-facing hillsides. An outdated regulation requires potential alcohol to reach 10% at harvest, but today it’s more of a problem to restrain alcohol. Even the most committed producers admit that it’s mostly impossible to get completely dry Pinot Gris or Gewürztraminer from Grand Cru sites: “Pinot Gris ripens very rapidly. Sometimes you say you harvest in the morning and it’s dry, you harvest in the afternoon and it’s sweet,” says Étienne Sipp (Louis Sipp). Marc Hugel adds, “Gewürztraminer will reach 13-14% when Riesling gets to 11%. It’s better to have 14% alcohol and 7 g/l sugar than 15% alcohol and bone dry.” Céline Meyer (Domaine Josmeyer) says, “If Gewürztraminer is completely dry it’s not agreeable because it’s too bitter.”

Now, a standardized sweetness guide will be required on all labels of AOP Alsace beginning with wines produced from the 2021 harvest. One option is for labels to contain a visual scale with sweetness levels and an arrow clearly pointing to one specific level. Slightly more information is available in the second option, a designation on each bottle of either Dry (sec): sugar content does not exceed 4 g/l; Medium-Dry (demi-sec): sugar content 4 g/l and 12 g/l; Mellow (moelleux): sugar content of the wine is between 12 g/l and 45 g/l and Sweet (doux): sugar content of the wine exceeds 45 g/l.

Domaine Albert Mann

According to David Schildknecht of The Wine Advocate, “The Barthelmé brothers, Jacky and Maurice, have maintained their position near the forefront of Alsace viticulture by farming a range of relatively far-flung and outstanding vineyards as well as offering excellent value virtually throughout their range.”

The fifty acres for which the Barthelmé are responsible are highly regarded throughout Alsace. Headquartered in the village of Wettolsheim near Colmar, the spirit animal of the operation is Albert Mann, Maurice’s father-in-law. He was the first to hit upon the idea of using modern production tools without neglecting the constraints of the land and his philosophy was to make wine using the elements of the soil, without the help of fertilizers. The Barthelmé brothers have embraced his beliefs and are now at the forefront of organic/biodynamic Alsace producers. The goal of the estate is to produce wine that is in harmony with nature: “Wine is the memory of the grape and is capable of transmitting the taste of the earth.’

The brothers began practicing biodynamic viticulture in 1997 in three of their Grand Cru vineyards, receiving certification from Biodyvin in 2015. This labor-intensive technique is intended to give the wine the purest reflection of its terroir and own identity. Says Maurice, “In ploughing the vineyards, we encourage the roots to descend to a maximum depth to capture the beneficial mineral elements from degraded rock below. Our holdings are divided up into a myriad of distinct plots, thus ensuring that each wine is reflective of their precise origins, while remaining as complex and multi-faceted as possible.”

The domain owns vines in five separate Grand Cru sites.

Hengst and Schlossberg are two of the better known. Hengst (meaning stallion) has a southeast orientation and shallow stony/calcareous soil while Schlossberg, with its steep, terraced slopes of granite, sand and shale, yields particularly expressive wines with pronounced floral bouquets. Both sites produce wines that age superbly.

Grand Cru Hengst

The Hengst Grand Cru lies in the commune of Wintzenheim, at the same latitude as Colmar, below the Hohlandsbourg Castle where altitudes are between 900 and 1200 feet on a steep, homogenous slopes. The vineyard faces south-east and benefits from the warm, dry Colmar microclimate.

Hengst soil structure is composed of oligocene conglomerates and lattorfian-interbedded marl. Although it is located in an early ripening sector, Hengst ripens grapes slowly and resists the development of noble rot. Rich in marl and trace elements, vines develop a high resistance to drought and easily avoid water stress. A significant presence of pebbles ensures that the soils are well drained. The high alkalinity of the soil and limestone substrate (45% active lime) may sometimes cause chlorosis (yellowing leaves) despite the soil being iron rich.

Hengst wines are powerful, complex and dense with bright acidity on the finish. They have great keeping potential, developing more expression with age.

Domaine Albert Mann, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Hengst Pinot Gris ($47)

Domaine Albert Mann, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Hengst Pinot Gris ($47)

Mann’s vines in Hengst are near the depression at the Cru’s center; the vineyard generally runs south-easterly with complicated geological strata that are quite visible to the naked eye. The wine is extremely concentrated and exotic with ripe mangoes, peaches and a core of preserved pears giving softness to the bright acids.

Grand Cru Furstentum

The Furstentum hillside nestles in the bosom of the Kaysersberg valley, where, with a southwest exposure, it is protected from the winds and thrives in an island of Mediterranean calcicolous vegetation. The brown, limestone soil is pebbly and porous with outcrops of bedrock. Covering 75 acres, the marl-limestone-sandstone originates in the Middle Jurassic period, covered at the end with Tertiary conglomerates.

The Cru has a steep grade (37%) to optimize the sun on a soil, allowing heat to accumulate through the day. It is primarily planted to Riesling, Gewürztraminer and Pinot Gris and produces wines of great finesse and remarkable aromatic weight.

D omaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Furstentum Pinot Gris ($45)

omaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Furstentum Pinot Gris ($45)

Furstentum’s iconic floral and blossom signature perfectly offsets the pear/apple of Pinot Gris. Approximately 35% of Alsace’s Grand Cru vineyards are planted to Pinot Gris, and this is a marvelous ambassador for the reason why. The intense, super-ripe pear notes are shored up by fresh pineapple and tangerine.

Domaine Albert Mann ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Furstentum Gewürztraminer ($45)

Domaine Albert Mann ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Furstentum Gewürztraminer ($45)

‘Vieilles Vignes’ refers to the fact that these vines are at least 45 years old; it is an archetypal Furstentum Gewürz with violet on the nose with a long-lasting backbone of Mirabelle plum, lychee, peach and unctuous lime marmalade, finishing on a slightly bitter note.

Grand Cru Steingrubler

Steingrubler vineyard sits just to the west of the village of Wettolsheim in the Haut-Rhin department of France. It is one of the more southerly of the Grand Cru sites in Alsace and covers an area of 56.7 acres, predominantly planted to Gewürztraminer. Steingrubler is one of four Grand Crus which run in a line just to the south-west of Colmar; Eichberg, Pfersigberg and Hengst are the other three. Pfersigberg is one of the largest Grand Crus in Alsace and for comparison Steingrubler is less than one-third of its size.

Sitting on the lower slopes of a granite promontory jutting out from the eastern Vosges, a topographical feature mirrored about a mile to the south at the Pfersigberg vineyard and again to the north in Hengst. The slopes enjoy a south-easterly aspect and soils have a heavy colluvial content—rough scree made up of granite, marlstone and limestone that improve drainage of the already dry site. The sandier soils higher up are mostly planted with Riesling, which makes up 26% of the vineyard. The richer clay and limestone below is well-suited to Gewürztraminer, making up 52% of the vineyard. The remaining 22% is Pinot Gris.

As well as being one of the driest vineyard sites in Alsace, Steingrubler is also considered a later-ripening vineyard. In the early-ripening vintage years the wine may be concentrated but remain elegant, combining aromas of candied fruit and, for Gewürz, bitter almonds.

Domaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Steingrubler Gewürztraminer ($45)

Domaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Steingrubler Gewürztraminer ($45)

Bright and perfumed with tropical breeze: Mango, passion fruit, crystallized papaya and fresh ginger dominate. Both silky and crystalline, the flavors of exotic fruit and sweet spice showcase magnificently why the Steingrubler is one of Alsace’s best Grand Crus for Gewürztraminer.

Grand Cru Schlossberg

With 200 acres under vine, Grand Cru Schlossberg is the largest of the region’s Grand Cru sites as well as the oldest, being the first Alsace vineyard granted Grand Cru status when classification began in 1975. It inherited its title from the castle (‘schloss’ in German) at its western edge, which it has stood guard over Kayserberg and the Weisbach Valley for 800 years. The vineyards are even older than the castle as the Roman colonists tended vines here more than 1,500 years ago.

The Schlossberg hillside is composed largely of granite, with the upper layers in an advanced state of decomposition. As a result, the topsoils contain a high proportion of coarse granitic sand, rich in potassium, magnesium and phosphorus of which are minerals that are found in few other vineyards. The distinctive style of Schlossberg Riesling wine is attributed largely to this unusual soil composition. As referenced, apart from a few notable exceptions, all Alsace Grand Cru wines are varietals and may be made from Gewürztraminer, Pinot Gris, Muscat or Riesling, and Schlossberg has each of these varieties planted, although it is particularly well known for its Riesling. It is entirely separate from the smaller Wineck-Schlossberg, two miles to the south.

Domaine Albert Mann, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Schlossberg Riesling ($88)

Domaine Albert Mann, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Schlossberg Riesling ($88)

A substantial, acid-ripped Riesling that, while exuding youth, is built for the ages. The nose is marked by hawthorn and lime blossom, while on the palate, citrus peel is underlined by a minerality that beautifully expresses the granitic terroir.

Domaine Weinbach

Named after the little stream which runs through the property, Domaine Weinbach was first planted with vines in the 9th century and established as a winery by Capuchin friars in 1612. After being sold as a national property during the French Revolution, it was acquired by the Faller brothers in 1898, who then left it to their son and nephew, Théo Faller. Following his death in 1979, his wife Colette and daughters Catherine and Laurence continued the family’s passion for great wines until the untimely deaths of Colette and Laurence. Since 2016, Catherine has led the estate winery with her sons, Eddy and Théo.

Domaine Weinbach owns 65 acres of vineyards in the Kaysersberg valley in the Haut-Rhin of Alsace at between 600 and 1300 feet above sea level. Vines are grown organically with a view to quality rather than quantity and grapes. Unlike most producers in Alsace, who purchase from négociants, Weinbach vinifies only estate grown grapes, and their aging philosophy is best described as passive, carried out in huge old oak foudres, a technique they believe allows each climat and each terroir (along with the other unique characteristics of grape and vintage) to shimmer through and produce elegant and sophisticated wines.

Domaine Weinbach, 2020 Alsace Grand Cru Schlossberg Riesling ($79)

Domaine Weinbach, 2020 Alsace Grand Cru Schlossberg Riesling ($79)

Wild herb and dried citrus zest drive a sensationally crisp wine with hints of mandarin orange, persimmon, jasmine and chamomile. The fruit is ripe and the acidity is vibrant, leading to an intense, long finish flecked with salty minerality.

Domaine Meyer-Fonné

Félix Meyer is one of those winemakers whom you sense is a star that will grow ever brighter with every vintage. He is the third generation in his family to be making wine since his grandfather founded Meyer-Fonné in the late 19th century and since taking over 1992, Félix has modernized equipment, developed export sales and is currently driving the family’s holdings deeply into the best vineyards of Alsace.

According to Félix, “Our vineyard covers eighteen hectares and seven communes, where the nature of the soils, the relief of the land and levels of exposure are varied. The soils range from poor quality filtering alluvial deposits (Colmar) to rich, deep clayey sandstone land in Riquewihr, with granite in between in Katzental, while the relief ranges from the flats of Colmar to the steeply sloping Katzental. The degrees of exposure are also very varied, ranging from the cooler western part which is suitable for the earlier vine types to the south-facing part which is very warm and sunny. This great variety of terroirs constitutes a distinctiveness and a richness in relation to many of the French vineyards.”

A stickler for detail with an overriding sense of responsibility, both his family and the earth, he makes his home in Katzental, known for its distinctive granite soils. With this remarkable terroir beneath his feet, Meyer has developed a knack for mixing wine from various of his parcels into complex and balanced cuvées. Among his cellar tricks is leaving wine to age on lees in large, older foudres, as was once the tradition in Alsace. All of Meyer’s bottlings are characterized by their stunning aromatics and signature backbone of minerality and electric acidity.

Grand Cru Wineck-Schlossberg

Wineck-Schlossberg lies between the communes of Ammerschwihr and Katzental in heartland of the Alsace. It is particularly known for its aromatic Riesling and Gewürztraminer. It is among a cluster of five sites immediately west of the region’s wine capital, Colmar, along with Brand, Florimont, Sommerberg and Kaefferkopf.

Wineck-Schlossberg vineyards cover 65 acres overlooking Katzental. The hillside is composed largely of granite like nearby Sommerberg, with the upper layers in an advanced state of decomposition. As a result, the topsoils contain a high proportion of granitic sand, rich in minerals not found in most other Alsace vineyards. The vines enjoy a south-southeasterly aspect, meaning that the vines are exposed to the ripening rays of the sun throughout the morning and into the afternoon. The slopes are nestled in a high sided valley which gives the site—already in the rain shadow provided by the Vosges mountains—plenty of protection from wind.

The wines are dry, showcasing a subtle balance between, minerality and crystalline fruit.

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2016 Alsace Grand Cru Wineck-Schlossberg Riesling ($45)

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2016 Alsace Grand Cru Wineck-Schlossberg Riesling ($45)

The crumbly binary mica granite known as ‘de Turckheim’ in the Wineck-Schlossberg Grand Cru gives this wine a pure and delicate with (as suits the winemaker’s name) Meyer lemon and fresh tarragon lacing white peach, grated ginger, lemon curd and stone notes.

Grand Cru Schoenenbourg

Schoenenbourg lines the south-facing hillside above the communes of Riquewihr and Zellenberg; at 132 acres it is one of the larger of Alsace’s Grand Cru sites. Although it is viewed as being at the core of Alsace’s prime vineyard belt, located in a crop of about ten Grand Crus between the towns of Colmar and Ribeauvillé, Schoenenbourg is slightly removed from the lower slopes of the Vosges Mountains where most of the other Alsace Grand Crus are to be found. The slopes rise steeply from 870 feet to around 1,250 feet from the northern walls of Riquewihr.

The soils are varied across this long, thin site, leading to variability in Schoenenbourg wines depending on the exact parcels of land where the grapes were grown. Marlstone, locally called Keuper after the geological period of the same name, is a dominant soil type, often covered by a fine layer of sandstone. The more unusual soil component here is gypsum, deposited when oceans covered the area during the Jurassic period more than 150 million years ago. Gypsum brings a particular combination of mineral richness to the wines; it also has a higher water-retention rate and is the secret behind Schoenenbourg’s botrytized wines from, sold as Selections de Grains Nobles.

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2017 Alsace Grand Cru Schoenenbourg Riesling ($50)

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2017 Alsace Grand Cru Schoenenbourg Riesling ($50)

Only ten cases of this wonderful elixir make it to the United States every year; it comes from a third of an acre of 30-year-old vines planted on the Cru’s typical ‘marne verte de Keuper’ soil. It is fermented in temperature-controlled stainless-steel tanks and oak barrels over a period of 1-3 months. It is a precise, dry, mineral-focused Riesling combining ripe apple flavors with bright lemon and shows subtle chalk on the finish.

Domaine Mann

After stints in Côte-Rôtie and Champagne, where he learned the value of biodynamics from Bertrand Gautherot, Sébastien Mann has been making wine at the family estate since 2009, taking over from his father. He says, “I think that thanks to biodynamics, we have succeeded in bringing an additional element to our vines. My father made wines essentially linked to the earth; I have a much more holistic style, linked to the stars.”

Domaine Mann’s 32 acres were founded upon the theory that in order to produce terroir-driven wines with aging potential, legally allowable yields have to be cut in half. From the outset, the estate produced 35 cuvées, one for each parcel.

“The style of the wines changed very quickly when I came on board,” Sébastien maintains. “95% of the wines we produce now are dry. It was not an easy task, since Alsace is one of the warmest and driest regions in France. Grapes can easily ripen with a high sugar level. I don’t think my father could imagine that with biodynamics we would be able to achieve such a great evolution, achieving phenolic maturity while making dry wines.”

Grand Cru Pfersigberg

Pfersigberg is the third-largest Alsace Grand Cru, covering 184 acres immediately to the west of Eguisheim. It is overlooked by the Trois Donjons the city’s three towers once used by agrarians as a timepiece, noting the position of their relative shadows to track the progress of the sun.

Pfersigberg slopes are some of the most gentle in Alsace, rising from 720 feet at their eastern edge to a little over a thousand feet in the west. There is a marked difference between the topography here and the steep, almost unmanageable slopes of Grand Cru sites of Zinnkoepfle and Rangen. The soil is predominantly limestone and marl with a higher quantity of clay than is usual this far away from the river basin. This clay reduces the drainage efficiency of the local soils.

Pfersigberg is one of the driest vineyard sites in Alsace and the climate of the area overall is continental, with marked low rainfall due to the shadow cast by the Vosges. The mountains also provide protection from the prevailing westerly winds.

The site produces wines with ample body and dense, straight-forward acidity marked by citrus fruits, notably limes. Nervous and willowy, the wine’s purity enhances the aromas of flowers and the minerality expresses itself in the length.

Domaine Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Pfersigberg Riesling ($69)

Domaine Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Pfersigberg Riesling ($69)

The techniques used in this dry, delightful wine include manual harvesting in boxes, gentle and long pressing times, natural fermentation on indigenous yeasts and aging on the lees for a year. The wine is juicy and transparent, presenting white peach and lime beside piquant hints of caraway, peach kernel, citrus zest and chalk.

Domaine Schoffit

To call a man a ‘pioneer’ who cultivates wine country that has been famous for eight hundred years (vintage 1228 was described as ‘extremely good; so hot you could fry an egg in the sand’) may seem a stretch, but the spirit that impelled Bernard Schoffit to purchase 16 acres around Clos St. Theobold belongs to a frontiersman. Previously abandoned because the slopes were deemed too steep to work, the vines in question (in Rangen de Thann AOP) grew on a plot of soil that has been likened to Montrachet and Chambertin. And from this forbidding site, relying on extremely low yields, he is making extraordinary wine with each cépage.

In addition, Schoffit raises grapes in the lieu-dit Harth, an alluvial terroir close to the commercial area of Hussen in northern Colmar, and three acres in the granitic Grand Cru Sommerberg to the south of Katzental and to the north of Niedermorschwihr. In Harth, Schoffit tends 80 years old Chasselas vines, of which a few percent are replanted each year as an illustration of Schoffit’s long-term perspective

Based near Colmar, Bernard took the winery over from his father Robert and his son Alexandre is now a co-owner. Demonstrating the estate’s commitment to sustainable agriculture Alexandre maintains, “All our vineyards are organic, and we also started to work biodynamic a few years ago. In order to show more transparency, I decided in 2016 to launch the official certification process, but for administrative reasons it was stretched over different years. The first wines officially labeled fully organic will be some cuvées of the 2019 vintage (Harth Riesling and Harth Pinot Gris for example), and the rest of the classic range will follow in the 2020 vintage. For the Grand Crus, it will be from the 2022 vintage. The official certification for biodynamic is in progress and we are still waiting to know from when we will be able to use it on the labels. But for now, Domaine Schoffit gives the assurance that we are both bio and biodynamic!”

Grand Cru Rangen

Volcanic upheaval is the name of the game at inconspicuous hillside adjacent to the town of Thann, making it a geological anomaly in the Vosges Mountains. But there even more bang for that buck—while ploughing Rangen acres that had abandoned for multiple generations, Olivier Humbrecht (Domaine Zind-Humbrecht) uncovered three unexploded bombs from World War II. Dotting the eastern slopes of the Vosges Mountains and is notable for more than just its terroir: Rangen is the only site in Alsace to be classified as Grand Cru in its entirety, and is home to the highly respected Clos Saint Urbain and Clos Saint Théobald vineyards.

In Rangen, the altitude climbs higher (1100 to 1525 feet) and the slopes have an average gradient of 60%. It is predominantly planted to Pinot Gris, the variety that accounts for 57% of vines; Riesling represents about a third of the site while Gewürztraminer is 10%. Despite its southerly aspect, Rangen is late-ripening, mainly due to its higher rainfall and cool winds which also make the site more prone to botrytis and its attendant Sélection Grains Nobles and/or Vendanges Tardives sweet wines.

The late-ripening terroir also increases power (and often alcohol) in the wines. Wines from Rangen are often described as having a ‘smoky’ taste.

Domaine Schoffit, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Rangen ‘Clos Saint-Théobald’ Riesling ($59)

Domaine Schoffit, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Rangen ‘Clos Saint-Théobald’ Riesling ($59)

The volcanic soils of Rangen, characterized by their low clay content, lie beneath one of the warmest plots in the region, a combination that generally pushes this Grand Cru to the top of the list. At 14.3% abv, it is precise and potent in comparison to a German Riesling, showing dried peach, lemon curd, fresh lime and Rangen’s classic, slightly resinous aromas of fresh rosemary.

SGN: The Quintessence of Alsace Wines

Alsace’s semi-continental climate sees very little rain and—especially in the autumn—remarkably consistent sunshine. This is ideal for extended ripening as well as the development of noble rot. Particularly suited to these effects Riesling, Muscat, Pinot Gris and Gewürztraminer d’Alsace, often several weeks after the normal harvest time when the berries are ultimately at their best.

Sélections de Grains Nobles grapes are obtained from harvesting grapes with noble rot where the driest berries are kept. This particularly high sugar content creates more discreet varietal flavor with enhanced intensity, complexity and remarkable length.

After substantial efforts undertaken by wine-makers, the official recognition of Sélections de Grains Nobles was made by a ministerial decree; March 1, 1984.

Domaine Albert Mann ‘Le Tri’, 2010 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Sélection de Grains Nobles SGN Pinot Gris ($126) 375 ml

Domaine Albert Mann ‘Le Tri’, 2010 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Sélection de Grains Nobles SGN Pinot Gris ($126) 375 ml

The residual sugar is met by a near-doubling of acidity leading to a beautifully balanced dessert-style wine powered by notes of candied lime peel, grapefruit marmalade, honey, marzipan, lanolin and vanilla.

The Upside of Climate Change: Pinot Noir is Taking Root in Alsace

Global warming is potentially an earth-ending reality, but if anybody is snatching victory from the jaws of defeat, it is Alsace. According to winemakers there, the overall increase in temperature, though only a few degrees, is enough to allow their Pinot Noir to ripen more fully, producing wines with greater concentration, both in flavor and color.

This is a remarkable turn of events, since 90% of all wines produced in Alsace are white, made from the multitude of varieties mentioned above. The surprise of the century, Pinot Noir d’Alsace quality levels not only from warmer, dryer summers, but because of a dedication of winemakers to plant the grape in higher-quality growing areas once reserved for prized white varieties. Pinot Noir plantings are skyrocketing in Alsace, rising from 2% in the last century to more than 10% today.

If the trend continues (and there is no reason to suppose it won’t) we will likely be introduced to a Pinot Noir Grand Cru, and sooner rather than later—likely before the end of the planet.

Domaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Pinot Noir lieu-dit ‘Clos de la Faille’ ($88)

Domaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Pinot Noir lieu-dit ‘Clos de la Faille’ ($88)

The Clos de la Faille monopole is just under three acres located near the Grand Cru Hengst; it is the only Clos in Alsace planted with 100% Pinot Noir. It is divided into three sections—the upper part consisting of pink, mottled and calcareous sandstone; in the middle, there is grey shell limestone with a very fine grain and yellow Jura rock, and in the lower part, a mixture of Vosges sandstone and white and pink quartz; the vines were planted between 1998 and 2002. The wine shows a nice leather and forest-leaf profile, opening to blackberry, cedar, smoke and chocolate.

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2017 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Pinot Noir ($48)

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2017 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Pinot Noir ($48)

Among the best of Alsace’s new guard of Pinot Noirs, this seductive wine, with seductive notes of tea leaves, strawberries and blackberries, is in the class of many Premier Cru Burgundies. It is spectacular now, and should improve for a decade.

Domaine Weinbach, 2019 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Pinot Noir ($110)

Domaine Weinbach, 2019 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Pinot Noir ($110)

Lieu-dit Altenbourg lies at around 800 feet elevation just below Grand Cru Furstentum. Wines from this terroir are made from grapes harvested in the Kientzheim-Kaysersberg valley, just below the foothills of the Vosges Mountains. Although it does not possess Grand Cru status itself, Altenbourg is considered as good as many Crus that do hold the title. The wine is rustic and redolent with scents of cranberries, strawberries and raspberries with supple, soft tannins.

Domaine Weinbach ‘S’, 2019 Alsace Pinot Noir ($110)

Domaine Weinbach ‘S’, 2019 Alsace Pinot Noir ($110)

According to Catherine Faller, Domaine Weinbach’s third-generation proprietor, “Pinot Noir is to red wine what Riesling is to white wine. Neither copes with mediocrity.” As a result, the goal is low yields and perfect grape maturity. The grapes in the ‘S’ series were sourced from the Grand Cru vineyard Schlossberg and offer elegant, fresh cherry and herb on the nose and a supple mouthfeel with some sappiness.

Domaine Schoffit ‘Vieilles Vignes Vendange Entière’, 2018 Alsace Pinot Noir ($33)

Domaine Schoffit ‘Vieilles Vignes Vendange Entière’, 2018 Alsace Pinot Noir ($33)

‘Vendange Entière’ refers to whole-cluster fermentation—a cellar technique intended to make a given wine more complex, weaving in spicy and herbal while adding candied and airy fruit and tannin structure, and also, to smooth out high acidity. In short, it is a method winemakers use to override anything lacking in a cool climate Pinot. Here, it works, and the wine is finely knit, featuring crushed black cherry, mandarin orange peel, Herbes de Provence and anise notes.

Domaine Valentin Zusslin

Aligned with the same winemaking traditions it first established in 1691, Zusslin is located in the southern part of Alsace in Orschwir on the Bollenberg, Clos Liebenberg (a Zusslin monopole) and the hillsides of Pfingstberg Grand Cru.

Early to the Crémant game, the domain was also an early practitioner of biodynamics, having introduced this philosophy to viticulture in 1997. Says Valentin (whose name, perhaps, makes this an iconic sparkling wine for February 14): “We plant cover crops to encourage good insects and microbial life for the soil, encourage bees to pollinate the beneficial plants and we grow trees to attract the birds that eat the harmful bugs. This way of thinking carries through everything we do in the fields and in the winery.”

In addition, his wife Marie insists that their lifestyle goes far beyond a philosophy, and as evidence, she indicates the wall on the property that bears names of 13 generations of Zusslin winegrowers: “We represent not only history, but the circle of life.”

Domaine Valentin Zusslin, 2018 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Bollenberg’ Pinot Noir ($48)

Domaine Valentin Zusslin, 2018 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Bollenberg’ Pinot Noir ($48)

A biodynamic and 100% Pinot Noir from the long awaited 2018 vintage, the wine is from vines planted on the slopes of the Bollenberg lieu-dit, where the limestone equates to finesse and a salty undertone. The vineyard sits at the foot of the Vosges Mountains in one of the driest places in France with only about 15 inches of annual rainfall. Supple and silky, showing tones of cherry and minerality.

Notebook …

Winegrape Variety Over Geography?

Alsace has changed hands between Germany and France five times since 1681, the last time in 1945 when French finally became the official language. That said, the blats of the oompah band have not faded into the distant: Most of the vineyards have Germanic names and despite the official rule of thumb, the dialect spoken by Alsatians is a hybrid of French and German. Prior to the post World War I change of flags, Alsace was a main priority for the German authorities whose ultimate goal was Germanizing Alsace and its inhabitants, and wine was one of their first targets. During the war, occupied Alsace was prohibited from selling its wines using the region’s name. Winemakers were allowed to blend as they saw fit, even if doing so eliminated the distinctive characteristics that have come to be associated with Alsace. Riesling and Gewürztraminer—two of Alsace’s most significant grape varieties—were declared illegal.

Another upshot of this hybrid culture is that Germans have not historically be known to champion terroir. Certainly vineyards are of utmost importance to label classification and price, but sweetness levels and grape types are more the focus. As such, Alsace mentions the grape variety on the label, generally unheard-of in France. Terroir was never historically used to market wines in Alsace; the industry was organized to sell combinations of brands and varieties rather than shared vineyards.

Anne Trimbach (of the renowned Ribeauvillé domain) speaks of a recent change of heart: “When we leased a number of hectares from the convent, one of the conditions that the nuns put in place was that we would change our strategy and reference ‘Grand Cru’ on the label. The Family discussed it at length and decided that it was a natural progression. It just seemed like the right time to take that step, as I felt buyers and sommeliers were increasingly aware of and interested in terroir in Alsace.”

- - -

Posted on 2023.03.02 in France, Alsace

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Aglianico, Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Beaune, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Clairette, Corvina, Cot, Counoise, Erbamat, Ferrol, Fiano, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Fumin, Garnacha, Gewurztraminer, Godello, Graciano, Grenache, Grolleau, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Melon de Bourgogne, Merlot, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montepulciano, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscadelle, Muscat, Natural, Nero d'Avola, Parellada, Patrimonio, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Auxerrois, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Rondinella, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sangiovese, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Viognier, Viura, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- February 2004

Search