A Burgundy by Any Other Name: AOP ‘Régionale’ Burgundy From Côte d’Or’s Pedigreed Communes. Hidden (Affordable) Gems From Ten Outstanding Producers (10-Bottle Pack $457)

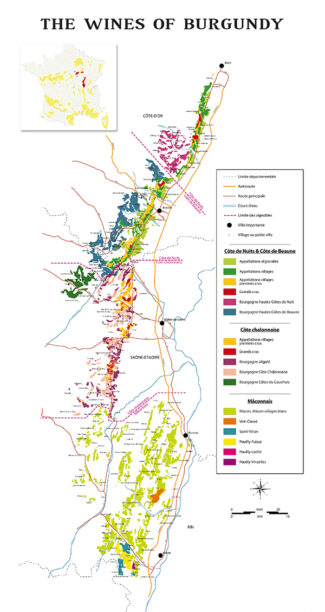

Not all Burgundy is the stuff of legend, but all is the stuff of Burgundy. That is, wine from a narrow strip of French farmland that runs for around sixty miles from Auxerre in the north to Mâcon in the south, or to Lyon, if Beaujolais is included. But Burgundy is more than simply wine; it is a way of thinking. After many centuries of experimentation and the subsequent subdividing of vineyards based on family inheritance, mesoclimates, soil types and topographical features, modern Burgundy exists as a mosaic of fences, walls and property lines.

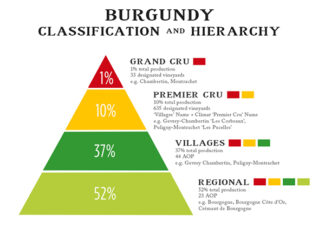

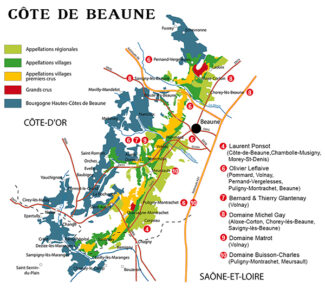

The most prestigious of these wines come from the 33 Grand Cru vineyards in the Côte d’Or; meaning literally, the ‘Hills of Gold’, further subdivided into Côte de Nuits and Côte de Beaune. The top domains produce rarified wines with stratospheric price tags, but represent only about 2% of Burgundy’s total 70,000 planted acres. Most of the wine produced in the appellation is regional wine—a fourth tier (after Grand Cru, Premier Cru and Villages) that accounts for 52% of Burgundy’s total output. White wines making up about half of that; red wine accounts for 27%, Crémant 21% and rosé a drop in the bucket at 1%.

The seven appellations contained within the ‘régionale’ classification produce earthy wines available at down-to-earth prices and represent a more complete understanding of Burgundy’s overarching philosophy of terroir. As such, régionale wines don’t seek to compete with the superlative top-shelf Crus of the Côte d’Or, and better still, many continue to fly under the radar.

Bourgogne (Régionale Bourgogne)

So specific are the cru vineyards of Burgundy that ‘régionale’ vineyards may exist in the literal shadow of more renowned domains, occasionally separated by hundreds, or even as little as dozens of feet. Régionale wines tend to be culled from vineyards located along the foot of more prestigious wine-growing slopes on limestone soil mixed with some clays and marls, where the earth is stony and quick-draining.

Unlike Bordeaux, where classifications are based on individual châteaux (capable of buying other vineyards and expanding), Burgundian label classifications are more geographically focused. A single vineyard, therefore, may have multiple owners, each with a small piece of the action.

The ‘Bourgogne’ label first appeared in 1937, and in 2017, a further classification permitted wines from vineyards located within the Côte d’Or to be labeled as ‘Bourgogne Côte d’Or’; it’s a great tool for a consumer looking to explore the wide diversity of vineyards among the Hills of Gold while maintaining a terroir-focused, climat approach to Burgundy.

Bourgogne AOP (Côte de Nuits)

The Côte de Nuits is the northern half of the Côte d’Or. Wines made from Pinot Noir dominate the area’s output, representing 95% of production. Some César is grown to bring backbone and color to Pinot Noir in weak vintages, but the proportion used is always minimal.

Having developed the reputation for quality over quantity, the Côte de Nuits is home to some of the finest red-wine vineyards in the world and includes 27 of Burgundy’s 33 Grand Cru appellations. Their mission statement spills over into the broadest appellation, Bourgogne, and makes these red wines among the best in the world for value. Any estate can declassify any lot from any Burgundian appellation and use this designation, and négociants know this: As a result, that $40 Bourgogne you enjoy may contain juice from vineyards whose names grace labels costing ten times as much.

Domaine Thierry Mortet ‘Cuvée Les Charmes de Daix’, 2020 Bourgogne ($33)

Domaine Thierry Mortet ‘Cuvée Les Charmes de Daix’, 2020 Bourgogne ($33)

‘Love thy neighbor’ is a rule no more golden than at the estate of Thierry Mortet, located at the very center of the village of Gevrey-Chambertin. Officially created in 1992 when Thierry’s father retired and his estate was divided between his two sons. Thierry wound up with ten acres, which he has grown to 21 acres spread over four villages, Gevrey-Chambertin, Chambolle-Musigny, Couchey and Daix, just to the west of Dijon.

Thierry, studied enology and viticulture in Beaune, and his wife Veronique were joined at the estate by their daughter Lise in 2020. Together they produce around 2,900 cases annually.

‘Les Charmes de Daix’ is produced from 6 different parcels amounting to three acres in total, planted on clay soils with chalky sub-soils. That portion of vines located in the commune of Daix provides delicacy and finesse while those from the commune of Gevrey bring structure and richness. The wine is fresh and fruity, elegant and generous with the aromatic persistence one expects only in much higher-priced Burgundy.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils ‘Terroir de Gevrey’, 2018 Bourgogne Rouge ($41)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils ‘Terroir de Gevrey’, 2018 Bourgogne Rouge ($41)

Local boy makes good’ is a common enough tale in Burgundy, where land—which can command a price tag twice that of Bordeaux—is generally held by families. Most success stories involve inheriting it or marrying it. Rare is the breakthrough of an outsider who can, for example, step off a train in Gevrey-Chambertin without connections or formal wine training and forge a Burgundian empire within an enclave already pretty imperialistic.

Enter Jean-Michel Guillon. Born into a military tradition, Jean-Michel Guillon chose to settle in France after his past service in the Polynesian Islands and in 1980, without much formal training, planted grapes on five acres of land. What began as a nascent fascination grew into an overarching passion, and the estate today covers nearly forty acres spread over more than 20 appellations. It is work that, like the best Gevrey-Chambertin wines, took years to peak, both stylistically and critically: 2020 turned out to be Jean-Michel Guillon’s best vintage ever.

He explains: “It is all the result of my love for this land, and any acclaim I have received is based on innovative production processes and more importantly, taking into account the ecological needs of the vine. The climate crisis and the scarcity of natural materials is taken very seriously at the winery. Global warming is at the heart of the destruction of habitat destruction and the appearance of certain diseases. In order to facilitate cultivation and harvesting, we have worked diligently worked to reduce our carbon footprint by using phytosanitary products that respect the environment.”

Among his most aggressive innovations may be his use of new oak—100% at all levels, including the Bourgogne Rouge, his entry-level wine. On this front he quotes Henri Jayer, perhaps Burgundy’s most inventive winemaker: “There are no great wines without new barrels.” As such, Guillon & Fils is the biggest buyer of new French oak in Burgundy after Domaine Romanée-Conti and the Hospices de Beaune, most arranged through a long-standing partnership with the Ermitage and Cavin cooperages.

Ruby-red and luscious, this mineral-driven, refined and light-footed Pinot-based Bourgogne from Gevrey-Chambertin shows a pure, ripe and elegant nose of cassis and lightly spiced plum that complements the balanced body. The wood for which Guillon is famous is prominent but not dominant, allowing the berry notes to ooze through.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils ‘Les Graviers – Chambolle’, 2018 Bourgogne Rouge ($41)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils ‘Les Graviers – Chambolle’, 2018 Bourgogne Rouge ($41)

Made of declassified Chambolle-Musigny, very few cases of this top price/value wine were made; the silky, ripe structure and whiffs of powdery vanilla makes the wine’s pedigree obvious. It is exceptionally rich with ripe, even sweet tannins and a serious and unusually powerful finish, especially in the context of the Bourgogne category.

Domaine Perrot-Minot ‘Gravières des Chaponnières’, 2018 Bourgogne Rouge ($75)

Domaine Perrot-Minot ‘Gravières des Chaponnières’, 2018 Bourgogne Rouge ($75)

After spending several years in Burgundy’s Cote d’Or working as a liaison between growers and négociants, Christophe Perrot‐Minot returned to his family domain in Morey‐Saint‐Denis. Prior to this prodigal homecoming, his father Henri had operated primarily as a grower, selling the majority of the family production in bulk. Christophe soon shifted the focus to estate bottling, and all but a small portion of Bourgogne-Passetoutgrain, a blend of Pinot Noir and Gamay, is now released under the family’s own name.

Today considered one of the benchmark producers in the Côte de Nuits, his wines have become more refined in every vintage. A combination of intense field work and innovation in the cellar over the past thirty years have raised the bar in his portfolio, aided in particular by his year 2000 purchase of Pernin‐Rossin, giving him many old‐vine parcels from which to draw fruit.

Among Christophe Perrot‐Minot’s many innovations has been a renewed focus on sorting during harvest; his goal of producing more elegant wines has been achieved through the use of less new-oak in aging as well as less extraction during fermentation. The wine is a blend from two vineyards located in Morey-Saint-Denis; one plot is 55 years old and the other, 25 years old. ‘Gravières des Chaponnières’ shows cherry brandy, earth and graphite with chalky tannins and a savory tang.

Laurent Ponsot ‘Cuvée des Peupliers’, 2017 Bourgogne Rouge ($68)

Laurent Ponsot ‘Cuvée des Peupliers’, 2017 Bourgogne Rouge ($68)

Laurent Ponsot left his namesake family business (Domaine Ponsot) in 2017 to pursue a new adventure with his son, Clément. “The official reason is that I’m at retirement age but I don’t want to retire,” he said. ‘‘I own some vineyards and have decided to create a négociant business, buying grapes from friends. I’ll have an involvement in the vineyard, so as not to be merely a buyer of grapes. It is a real joint venture.”

For Ponsot, winemaking is foremost a matter of terroir expression and according to him, every detail within the process is important, in the vineyard and in the cellar. He refers to ‘haute couture wines’ with as little as possible intervention in the natural process. His grapes are grown without the use of chemicals and in the winemaking process, without the addition of sulfites. Instead, he uses a neutral gas during barrel élevage. Nor does he use any new oak: ”As you know, I am resistant to the addition of an oak taste, which is like the addition of natural extracts of fruits or flowers in the wines: it comes neither from the terroir or from original grapes. I consider that the barrel is only a way to oxygenate the wine by respecting its aging cycle.” He has therefore been experimenting with alternatives to oak barrels for years now.

Cuvée des Peupliers is drawn from a parcel of vines just below the Route Nationale in Chambolle on the Morey line. Ponsot has farmed these vines since 2002, and despite the appellation, it remains pure Chambolle in personality—it is fleshy but silken, retaining a juicy grace through a long finish redolent with earthy, forest-floor notes.

Bourgogne AOP (Côte de Beaune)

“Climate change is a fact,” says Laurent Audeguin, agronomist and enologist at the French Vine and Wine Institute. “As temperatures rise, the best vineyard sites become too warm. Vines are subject to increased risks of spring frost, sunburn and drought. The resulting wines, once defined by their elegance, subtlety and gracefulness, are getting riper by the year.

As chilling as that prospect sounds, it appears unavoidable, and the silver lining in Burgundy is that once-borderline areas have begun to come into their own, while many of the old reliable names are planting new Pinot clones that accumulate less sugar and ripen later. And there are plenty to choose from: Although there are 47 officially allowed Pinot Noir clones, in reality, only a few are widely used.

Nobody can have a genuine bone to pick with the statement that today, Bourgogne-level wines from Côte de Beaune are considerably better than those of decades past.

Domaine Bernard & Thierry Glantenay, 2018 Bourgogne Rouge ($41)

Domaine Bernard & Thierry Glantenay, 2018 Bourgogne Rouge ($41)

With roots in the 16th century, Domaine Bernard & Thierry Glantenay is a family story with 500 years of history. Up until around fifteen years ago, the estate sold its grapes to négociants, but that changed with Thierry taking the reins from his father, and today, the full production is sold as domain bottlings. Having trained as an engineer, Thierry brings a meticulous attention to detail to his winemaking, using no more than 25% new oak for even his top wines in search of terroir expression; His lieu-dit wines are considered among the best in the region, with vines between 60 and 80 years old and there is no question that the Bourgogne represents a significant value amid today’s stratospheric Burgundy price tags.

Glantenay Bourgogne Rouge comes from 30-year-old vines grown in deep clay soil and results in a satiny wine filled with succulent aromas of blackberry and raspberry giving way to crunchy acidity and a generous core of fruit.

Domaine Buisson-Charles ‘Hautes-Coutures’, 2018 Bourgogne-Pinot Noir ($47)

Domaine Buisson-Charles ‘Hautes-Coutures’, 2018 Bourgogne-Pinot Noir ($47)

Following the retirement of Michel Buisson in 2008, his daughter Catherine and her husband Patrick Essa rose to the occasion like grape skins in a vat of fermenting must. The domain they inherited covers 30 acres, nearly all of it in Meursault. Their five parcels of Village-level vines now average over 65 years in age, while the oldest are nearing the century mark. There is a small parcel of Meursault ‘Tessons’, one of the great lieux-dits of the region, lying on the hillside above the southern half of the village, and there are tiny pieces of four exceptional Premier Crus. Only a few barrels of Charmes, Les Cras, Goutte d’Or and Bouches-Chères are produced each year. The wines are unique in their intensity and persistence, and are neither too lean nor too fat. Says Patrick, “Our mantra of freshness comes from the fruit and the soil, which produces grapes without overt acidity.”

From a pair of Pinot Noir parcels located between the villages of Meursault and Puligny-Montrachet, with vines over 50 years in age. Aging is done in barrels, 25% of which are new. The wine shows notes of violets and sweet bramble on the nose while the palate is filled with black cherry and ripe, slightly spicy plum.

Olivier Leflaive ‘Cuvée Margot’, 2019 Bourgogne Rouge ($40)

Olivier Leflaive ‘Cuvée Margot’, 2019 Bourgogne Rouge ($40)

So renowned is the name Leflaive in Burgundy that no real history is required, but for the record, the family has been rooted in Puligny-Montrachet since 1717. Joseph Leflaive steadily acquired parcels of exceptional Premier Cru and Grand Cru vineyards in the twentieth century and was one of the precursors of domain bottling.

In 1985 Olivier started his own domain, focusing solely on buying grapes and managing vineyards with a team he directed himself. With this new team, he was able to source wines from outside of Puligny-Montrachet. In 1995, Olivier Leflaive in mutual agreement with his family, left Domaine Leflaive to concentrate on Maison Olivier Leflaive. Today, he controls 50 acres of vineyards located mainly in Puligny-Montrachet, Chassagne-Montrachet, Meursault and Pommard and in 2010, recovered its ownership in legendary vineyards managed by Domaine Leflaive after the lapse of an 18-year lease to the Domaine.

‘Cuvée Margot’s’ winemaker, Franck Grux, was kind enough to share details of this wine, and further embellishment is unnecessary: “As usual, these grapes used in 2019 came from different classified vineyards through the Côte de Beaune; 30% from Pommard, 20% from Volnay and 20% from Meursault. Pernand Vergelesses contributed 15%, while a sector of Puligny gave us 10%; the rest came from Hautes-Côtes de Beaune. They received one week of primary fermentation followed by two weeks of gentle cuvaison. The wine saw 15% new oak for one year and was bottled just before Christmas, 2020 without fining.” It shows refined nuances of black currant, red fruit, earth, spice, and alluring floral aromatics with remarkable complexity.

Domaine Thierry et Pascale Matrot, 2019 Bourgogne Pinot Noir ($35)

Domaine Thierry et Pascale Matrot, 2019 Bourgogne Pinot Noir ($35)

In 1914, Joseph Matrot and his wife Marguerite took up residence in Marguerite’s family home with the intention of developing the property into a respected wine estate. Over the course of several generations, Domaine Matrot expanded to fifty acres, and in 2000, began harvesting the vineyards organically. Of the change, Thierry Matrot says, “It’s not a revolution, it’s just an evolution. Technology has made things easier, but our winemaking philosophy has changed very little. The vinification is about the same. We don’t use new oak for the village wines or the Premier Crus; we prefer to allow the terroir to express itself and to show the character of each vintage. And my father worked in just the same way.”

The estate extends across five villages, producing both regional appellations and several Premier Crus in Meursault and in neighboring Puligny-Montrachet.

The grapes used in Matrot’s 2019 Bourgogne Pinot Noir are harvested in two plots at the bottom of the Volnay-Santenots slopes; the wine is structured and fleshy, showing blackberries, red currants, warm pie spice and underbrush notes behind fine tannins and a complex finish.

Domaine Michel Gay et Fils, 2017 Bourgogne Côte-d’Or Rouge ($36)

Domaine Michel Gay et Fils, 2017 Bourgogne Côte-d’Or Rouge ($36)

Great wines may be made in the vineyard, but the finesse is often created on the sorting table. When Sébastien Gay took over Domaine Michel Gay after his father’s 2001 retirement, among the improvements he initiated was a shift to organic farming, doing multiple “green harvests”, limiting yields by hand-pruning the vines and adding a pair of sorting tables where dozens of workers determine the quality levels of individual grapes. According to Sébastien, “Our wines show more balance now because modern techniques allow us to better control the different steps in the winemaking process.”

At just over 25 acres, the estate is relatively small, but it incorporates vineyard plots in communes with storied names and spreads across a kaleidoscope of terroirs, including Chorey‐lès‐Beaune, Aloxe‐Corton, Savigny‐lès‐Beaune Premier Crus Aux Serpentières and Les Vergelesses, three Premier Crus in Beaune, Les Toussaints, Aux Coucherias, and Les Grèves, as well as a small parcel on the Corton hill in the Renardes vineyard. Vines are between forty and sixty years old, and receive the same individualized attention as the grapes do at harvest. A fifth-generation winemaker, Sébastien has embraced modernity while revering tradition and the result is a portfolio of wines that see improvement with nearly every vintage.

The AOP ‘Bourgogne Côte d’Or’ encompasses 40 villages between Dijon and Maranges; as a restriction within the general Bourgogne AOP, it is fairly new, intended to highlight the unique potential of the Côte d’Or to produce wines superior to either Yonne or Saône-et-Loire. Michel Gay’s 2017 displays a solid, fleshy Burgundian profile, with ripe cherry, cinnamon, forest floor and a soft tannic backbone.

Notebook …

Vintage Journal

2020: Voluptuous and Structured

Despite the hot and dry conditions, Sarah Marsh MW characterizes 2020 Côte de Nuits as ‘joyously fresh in a vibrant, classically style.” Cool nights offset the heat and allowed the all-important acids to develop on schedule, but the harvest itself came uncommonly early, with some growers starting as early as August 20th and finishing by September 2nd, the earliest on record. Côte de Nuits reds from 2020 are noted for their big tannins and fine perfume.

2019: Concentrated and Vibrant

Excitement around the 2019 Burgundy vintage remains high, although the summer put climate change front and center; much of the crop was lost due to vines either being too stressed or grapes being sunburnt. The berries that did survive were, in general, richly concentrated. The red wines are, in general, complex, richly fruit-forward and refined, with the best examples likely to cellar well. The whites are also extremely concentrated, rich, and ripe, but without losing the crucial balance and elegance. In both categories, small yields means limited allocations, particularly of the top wines, and demand is high.

2018: Solar, Voluptuous with Immediate Appeal

Noteworthy for having the hottest and driest growing seasons since the intense heatwave of 2003, 2018 provided perfect weather during flowering and again at harvest, with some drought between. The crop was among the biggest in years with the red wines of Côte de Nuits acclaimed for being mostly complex wines, enjoyable young, with good potential to age.

2017: Supple and Accessible

Low yields may or may not produce excellent vintages, but high yielding vintages like 2017 tend to produce what the French refer to as ‘restaurant wines,’ meaning that they offer plenty of fragrance, attractive fruit, lacy tannins, reasonably strong terroir characters and an overall air of approachability. 2017 was the most consistent growing season in several years, and many of the vines that had suffered badly in the previous year’s frosts went into overdrive and were, in some cases, overladen with fruit. Some producers chose to green harvest to counter this problem, as too much fruit can result in a lack of concentration in the individual berries. The Pinot Noir harvest began in early September and was finished before the heavy rains of October set it, leading to some spectacular wines.

- - -

Posted on 2023.01.24 in Maranges, Ladoix-Serrigny, Chambolle-Musigny, Vosne-Romanée, Savigny-lès-Beaune, Pommard, Hautes-Côtes de Nuits, Volnay, Chorey-lès-Beaune, Pernand-Vergelesses, Monthélie, Côte de Nuits, Puligny-Montrachet, Aloxe-Corton, Morey-Saint-Denis, Beaune, Vougeot, Premeaux-Prissey, Chassagne-Montrachet, Auxey-Duresses, Nuits-Saint-Georges, Meursault, Saint-Romain, Marsannay, Côte de Beaune, Blagny, Côte de Beaune, Gevrey-Chambertin, France, Burgundy, Wine-Aid Packages

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Aglianico, Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Beaune, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Clairette, Corvina, Cot, Counoise, Erbamat, Ferrol, Fiano, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Fumin, Garnacha, Gewurztraminer, Godello, Graciano, Grenache, Grolleau, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Melon de Bourgogne, Merlot, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montepulciano, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscadelle, Muscat, Natural, Nero d'Avola, Parellada, Patrimonio, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Auxerrois, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Rondinella, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sangiovese, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Viognier, Viura, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- February 2004

Search