Beaujolais’s Pleasure of Now: Cru Moulin-à-Vent Wine Finds a Balance Between the Cerebral and the Carnal. Eight Producers in a Dozen Wines.

Saturday Sips: A Taste of Moulin-à-Vent

Come as you are; come any time that’s convenient for you during our business hours to sample selection from this week’s selections. Our staff will be on hand to discuss nuances of the wines, the terroirs reflected, and the producers.

Elie

The word ‘truism’ is rarely used with wine, a wondrous world where there as many exceptions as there are rules. One such example is price points: Whereas a ten dollar bottle of well-made wine is a better bargain than a hundred dollar bottle of flawed wine, in general, less expensive wines tend to be linear, intended to showcase a vineyard’s fruit and are meant to be consumed young. Pricier wines are constructed for the long haul and will improve markedly if allowed to mature under ideal conditions—for a year, two years, ten years and so on, depending on the label. They are complex wines that I have always considered to be ‘liquid memories.’ Intended to be consumed on special occasions—or in some case, being so special of themselves that consuming them becomes the occasion.

And now, the exception: Cru Beaujolais villages, which has in recent years striven to provide both modes of expression with equal intensity—wines that can be enjoyed in their heady, sensuous youth and will also mature with marked dignity.

Gamay, when grown in granitic soils and handled with expertise in the cellar, is the rare grape that can fulfill either destiny. Syrah-like in warm seasons and more like Pinot Noir when the vintage is cooler, Beaujolais’s workhorse monarch displays a chameleon-like versatility that shines in this region brighter than anywhere else in the world.

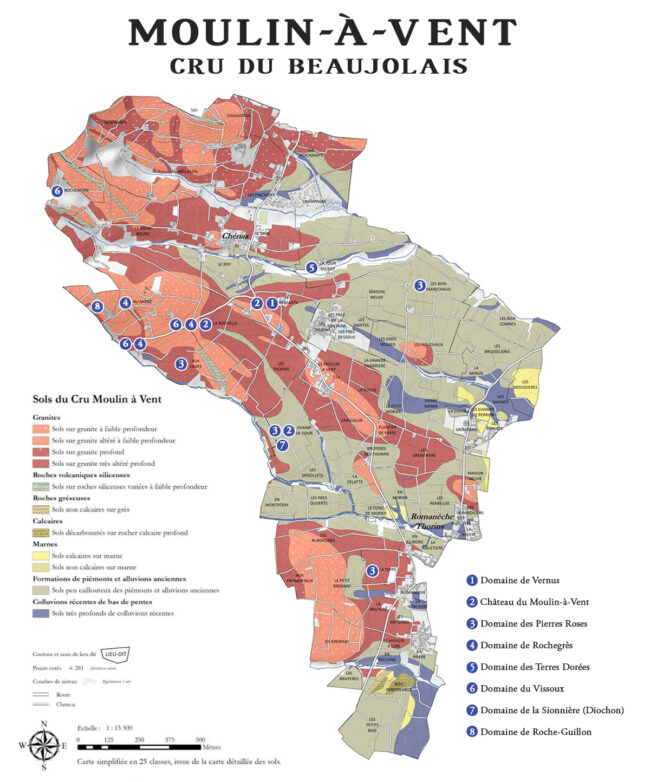

This week, we’ll focus a lens on Moulin-à-Vent, one of ten Cru-level appellations. Iconic both in terms of image and durability, the ‘windmill’ appellation is known for terroirs containing streaks of manganese winding through the granitic soils, and this mineral is said to augment the tannins naturally produced by Gamay.

Beaujolais’s Gamay: Wines of Contemplation and Complexity, Yet Provide Immediate Gratification.

‘The pleasure of now’ seems to be a 21st century operative, and when lighting delivery is the mandatory expectation, Gamay’s ability to deliver the goods within a year or so of bottling have it well-positioned to fill this need. Long appreciated for its hedonistic burst of fresh, grapey quaffability, Gamay’s more brooding face was kept as a guarded secret by the Cru cult, who often turned their noses up at plebian versions and relished in the meatier versions grown in hallowed vineyards.

But these noses should have been placed in the glass. Much of Beaujolais’ signature aromatics come from carbonic maceration, a method embraced (at least in part) by most Beaujolaisien winemakers in all appellations. In this style, intact grape bunches ferment inside their own skins with carbon dioxide used as a catalyst, either introduced or occurring naturally as a byproduct of fermentation. Once the alcohol reaches 2%, the grapes burst and release their juice naturally, whereupon a normal yeast fermentation finishes the job.

Even wines only partially fermented via carbonic maceration show bright fruit with aromas that bounce from the glass. A hybridization of these two faces of Gamay, which some call ‘street carbo,’ has as many varieties as there are experimentative winemakers. The complexity in the top-shelf Beaujolais are the result of superior fruit and—especially among practitioners of ‘Burgundy-style’ Beaujolais—from the oak-aging that is becoming more common.

Either way, the 21st century movement in Beaujolais is a step away from wines that could, even in the most cynical interpretation, be called ‘standardized.’

The Beaujolais Underground: A Veritable Mosaic of Soil

The biggest error a Beaujolais neophyte makes is an expectation one-dimensional predictability. To be fair, the mistake easy to make based on the region’s reliance on Gamay, a grape that elsewhere may produce simple and often mediocre wine.

In Beaujolais’ wondrous terroir, however, it thrives.

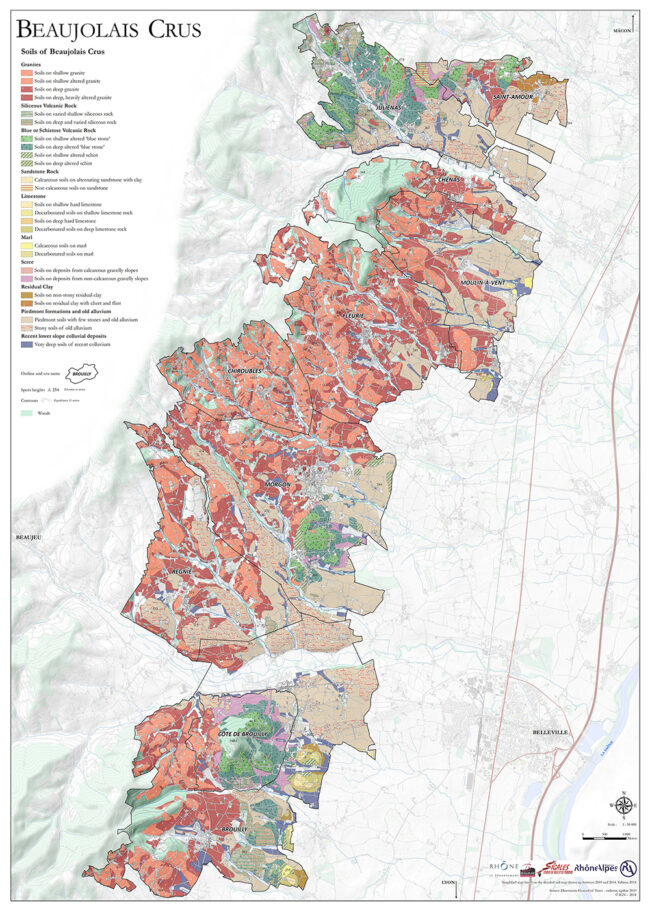

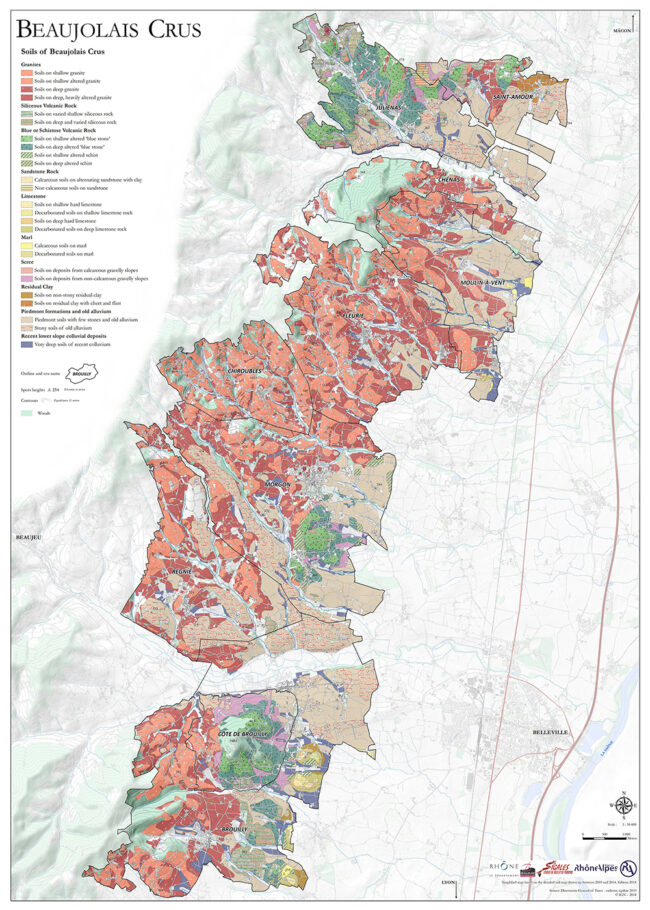

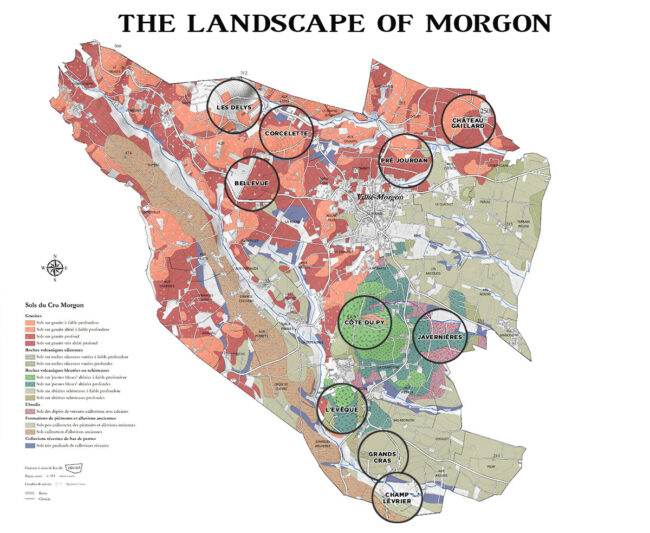

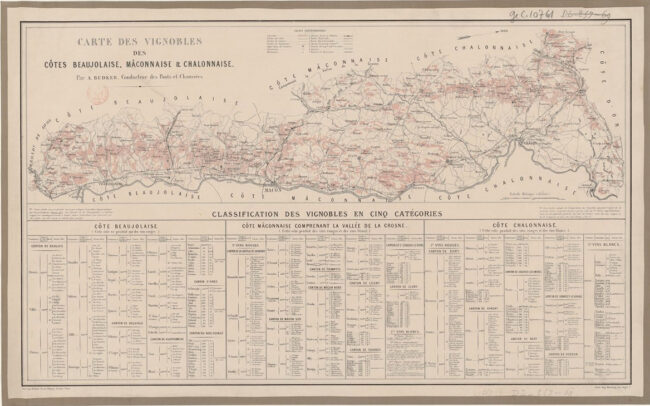

In fact, this terroir is so complex that it nearly defies description. But Inter-Beaujolais certainly tried: Between 2009 and 2018, they commissioned a colossal field study to establish a detailed cartography of the vineyards and to create a geological snapshot of the exceptional richness found throughout Beaujolais’ 12 appellations.

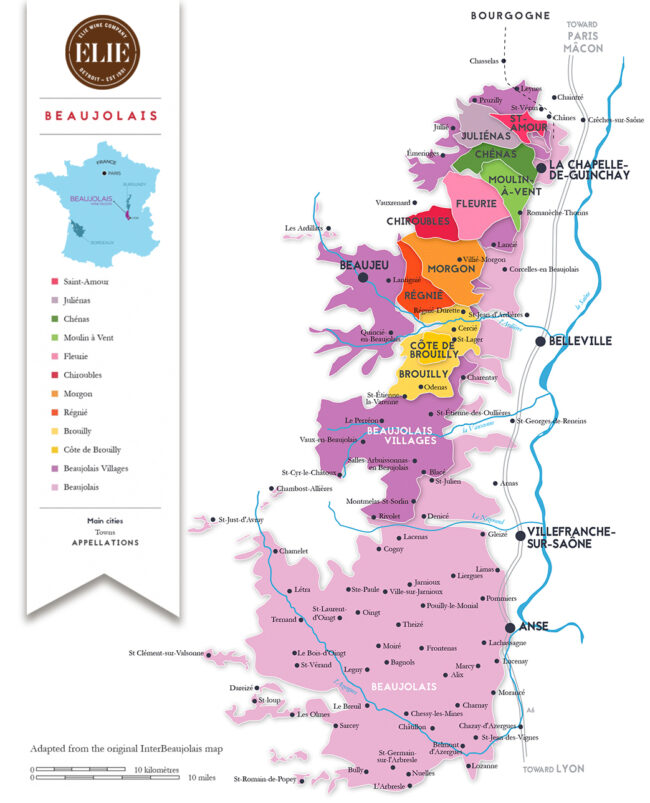

Beaujolais may not be geographically extensive, but geologically, it’s a different story. The region bears witness to 500 million years of complex interaction between the eastern edge of the Massif Central and the Alpine phenomenon of the Tertiary period, leaving one of the richest and most complex geologies in France. Over 300 distinct soil types have been identified. Fortunately, Gamay—the mainstay grape, accounting for 97% of plantings—flourishes throughout these myriad terroirs. In the south, the soil may be laden with clay, and sometimes chalk; the landscape is characterized by rolling hills. The north hosts sandy soils that are often granitic in origin. This is the starting point wherein each appellation, and indeed, each lieu-dit draws its individual character.

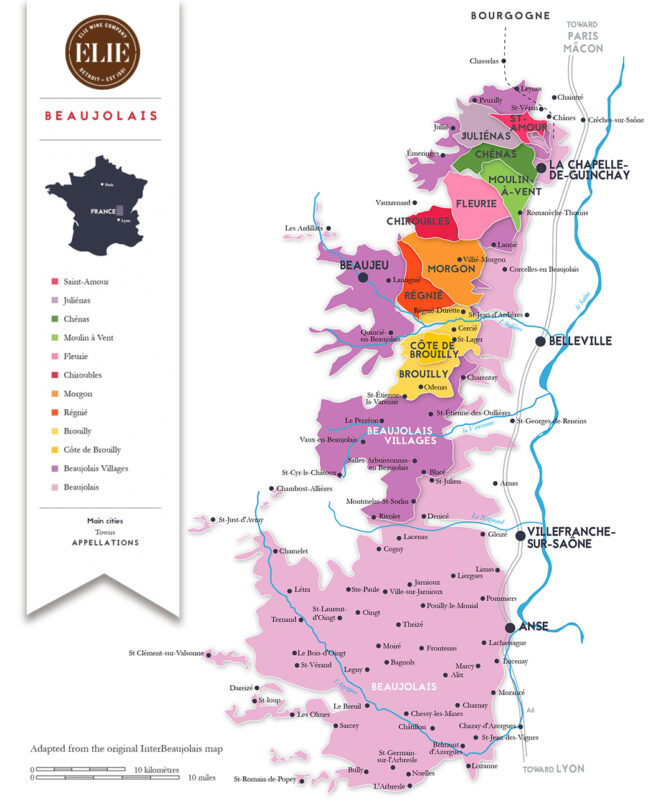

There are ten Crus, the top red wine regions of Beaujolais, all of them located in the hillier areas to the north, which offer freer-draining soils and better exposure, thereby helping the grapes to mature more fully.

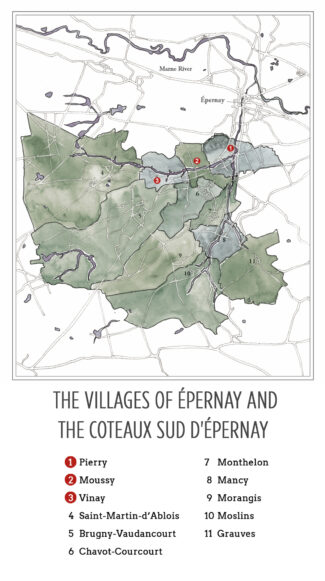

Courtesy of Wine Scholar Guild

A Palette of Ten Crus

Beaujolais is a painter’s dream, a patchwork of undulating hills and bucolic villages. It is also unique in that relatively inexpensive land has allowed a number of dynamic new wine producers to enter the business. In the flatter south, easy-drinking wines are generally made using technique known as carbonic maceration, an anaerobic form of closed-tank fermentation that imparts specific, recognizable flavors (notably, bubblegum and Concord grape). Often sold under the Beaujolais and Beaujolais-Villages appellations, such wines tend to be simple, high in acid and low in tannin, and are ideal for the local bistro fare. Beaujolais’ suppler wines generally come from the north, where the granite hills are filled with rich clay and limestone. These wines are age-worthy, and show much more complexity and depth. The top of Beaujolais’ classification pyramid is found in the north, especially in the appellations known as ‘Cru Beaujolais’: Brouilly, Chénas, Chiroubles, Côte de Brouilly, Fleurie, Juliénas, Morgon, Moulin-à-Vent, Régnié and Saint-Amour.

Each are distinct wines with definable characteristics and individual histories; what they have in common beyond Beaujolais real estate is that they are the pinnacle of Gamay’s glory in the world of wine.

Cru Moulin-à-Vent: Syrah-like in warm vintages, Pinot Noir-like in Cooler vintages

To the ten crus of Beaujolais, Moulin-à-Vent is what Moulin Rouge is to Parisian cabarets: First among equals. Of course, that equality is a matter of taste—some consumers prefer floral Fleurie and charming Chiroubles to the full-bodied, tannic-structured Moulin-à-Vent and it’s no secret that Georges Duboeuf manages to sell a hundred thousand cases of Beaujolais Nouveau a year.

Forgetting the forgettable and concentrating on the myriad styles of Cru Beaujolais, nowhere is the evidence of terroir—the site-specific contributions of geology, sun-exposure and rainfall—more obvious than in Moulin-à-Vent. Although each appellation works with a single grape variety, Gamay, the results range from light, glorified rosé to densely layered, richly concentrated reds that rival Burgundian Pinot Noir cousins from the most storied estates.

Moulin-à-Vent is unusual for a number of reasons, and among them is the fact that there is no commune or village from which it takes its name. Like the Moulin Rouge, the appellation is named for the ‘moulin’—windmill—that sits atop the hill that overlooks the south- and southeast-facing vineyards. The most outrageous reality of the Cru, however, is that the wine owes its structure and quality to poison: Manganese, which runs in veins throughout the pink granite subsoil, is toxic to grapevines and results in sickly vines that struggle to leaf out and produce small clusters of tiny grapes. It is the concentration of the juice in these grapes that gives Moulin-à-Vent a characteristic intensity unknown in the other crus of Beaujolais, where manganese is not present. It also gives the wine the foundation of phenolic compounds required for age-worthiness; Moulin-à-Ventis among a very select few of Beaujolais wines that can improve for ten, and even twenty years in the bottle.

Domaine de Vernus

After thirty years in the prosaic world of insurance brokerage, Frédéric Jametton decided to do a rakehell turn on his career trajectory. Having been born in Dijon and lived in Burgundy for most of his life, he had become an enlightened wine lover. Not only that, but his former profession brought him in contact with numerous members of the wine community. At the end of 2017, he realized that the time had come to invest in a winery.

Initially looking in the south, he became convinced that the heat spikes brought on by climate change made it unsuitable for the long haul, and after discussions with his friend Guillaume Rouget of Flagey-Echézeaux (who agreed to come on board as a consultant) Jametton settled on Beaujolais, piecing together 30 acres of vineyards acquired from 12 different proprietors, and is gradually restructuring parcels with a view to more sustainable farming.

Among his more valuable pieces of real estate is Les Vérillats in Moulin-à-Vent, where the sandy granitic soils are rich in iron oxide, copper and manganese.

Winemaker Guillaume Rouget, left, with Frédéric Jametton, Domaine de Vernus

Thanks in part to Rouget’s influence, vinification is conducted along Burgundian lines, with around 70% of the grapes destemmed and fermented in stainless steel with élevage in recently-used, high-quality Burgundy barrels for some 10–11 months. Jametton’s ultimate goal, echoed by Rouget, is to offer a range of wines that brings out the best of the different terroirs while respecting the character and personality of each Cru and each plot. With Rouget in charge of the vineyards and winemaking process, Frédéric remains at the management helm and spearheads marketing.

Domaine de Vernus, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Les Vérillats’ ($64)

Domaine de Vernus, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Les Vérillats’ ($64)

Les Vérillats lieu-dit is considered one of the top terroirs in Moulin and is known for producing small, concentrated grapes, even from vines of the relatively young age of 27. The harvest is by hand; destemming is 100% and cold maceration is followed by three weeks of natural fermentation and then, aging in oak barrels, of which 11% new. The wine shows translucent purples with a fine balance of bright red fruit and lightly glinting acidity.

Domaine de Vernus, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Les Vérillats’ ($162) en magnum

Domaine de Vernus, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Les Vérillats’ ($162) en magnum

The above wine in magnum, which will allow a fuller and more carefully controlled maturation process.

Château du Moulin-à-Vent

Château du Moulin-à-Vent has a history as unique and fascinating as the wine. In the late 1700s, Philiberte Pommier discovered that certain plots on her estate yielded better wines than others, and set out to understand the geology that underscored a self-evident truth. She began to tailor her winemaking to individual lieux-dits in her property (then called Château des Thorins), and in 1862, Pommier’s wines were deemed the best in the Mâcon region at the Universal Exhibition of London. At the time, Philiberte Pommier was 99 years old.

Édouard Parinet & Brice Laffond

Today, the estate encompasses nearly a hundred acres and covers some of the appellation’s finest climats—Les Vérillats, Le Champ de Cour, La Rochelle—with an average vine age of over forty years. The pink granite soil is rich in iron oxide, copper and manganese, and since 2009, under the new ownership of the Parinet family, investment in the winemaking facilities and the vineyards has resulted in plot-specific signature wines.

Château du Moulin-à-Vent, 2019 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Les Vérillats’ ($57)

Château du Moulin-à-Vent, 2019 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Les Vérillats’ ($57)

Lieu-dit Vérillats is a high-altitude, east-facing site with only a thin layer of granite sands at the top of a granite mount—poor and porous soil that yields around 25 hectoliter/hectare. These conditions lend themselves to a serious, nearly tense wine with iron notes and graphite. These harsher notes are leavened by bright savory fruit and finely-textured tannins with some dark chocolate on the finish.

Château du Moulin-à-Vent, 2019 Moulin-à-Vent ‘La Rochelle’ ($72)

Château du Moulin-à-Vent, 2019 Moulin-à-Vent ‘La Rochelle’ ($72)

Lieu-dit La Rochelle sits on a côte, and hosts a thin layer of granite sands over very fine clays. Average yield here are 15hl/ha. with southerly exposures and an altitude of 920 ft. The wine is perfumed with summer strawberries and lifted notes of white pepper with fine and supple tannins. The finish excels; it is sharp and focused and showcases the site’s minerality.

Château du Moulin-à-Vent, 2019 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Champ de Cour’ ($58)

Château du Moulin-à-Vent, 2019 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Champ de Cour’ ($58)

Lieu-dit Champ de Cour sit at the bottom of the hill overlooked by the iconic windmill; its soils are varied forms of eroded granite and white alluvial clays. The lower elevation tends to mean deeper soil, so water retention is better. The wine is spicy and opulent with Moulin-à-Vent’s muscular typicity.

Thibault Liger-Belair

Domaine des Pierres Roses

Winemaking has been the legacy of Liger-Belair family for a quarter of a millennium. Prior to establishing his own domain, Thibault Liger-Belair studied oenology, worked for a communications firm in Paris and started an internet company to discover and sell high quality wines. Still, the vines beckoned, and in 2001, at the age of 26, he returned to them. The following year saw his first harvest of Nuits-Saint-Georges, and in 2003, he expanded into Richebourg Grand Cru, Clos Vougeot Grand Cru and Vosne-Romanée Premier Cru Petits Monts. In 2009, he ranged farther afield, into Beaujolais, and now produces Beaujolais-Villages and several Moulin-à-Vent wines.

Thibault Liger-Belair

Although his Moulin wines are labeled as Liger-Belair, he speaks of his journey to Beaujolais under the name ‘Domaine des Pierres Rose’:

“Having completed a part of my studies in Beaujolais region, I have always been very attracted by the beauty of this region, its landscapes but also the quality and diversity of its soils. I then asked myself the question: why not create a Burgundian model by isolating each terroir within the same appellation in order to try to understand it and then make the most of its identity? My ever-growing curiosity has always made me want to understand other soils and other grape varieties, so that I can start again what I had built in Nuits-Saint-Georges in 2001, in Moulin-à-Vent in 2009.

To create the estate and buy the vines I have already tried to understand the different types of soil by asking the winemakers, by tasting the wines, but above all by walking through the vineyard. What surprised me first of all was to see so many differences in such a small area, it reminded me of the Burgundian terroirs. However, almost none of the producers were making differences between each of their vintages. Indeed, if they have vines in Moulin à Vent, they make a Moulin à Vent cuvée without isolating the different types of soil by different vintages. It’s hard to understand when you have a Burgundian approach that is based on the principle of isolating each of the plots.

So, I had the idea to acquire the best plots of land in the area, all located on the historical hillside of the appellation overhung by the Moulin à Vent, with the objective: to understand and to produce wines that stick to their climat as well as their grape variety: Gamay. The first plots were bought in 2008, in order to produce the first vintage in 2009. We have reproduced the same working methods as the ones as in Nuits-Saint-Georges by reintroducing ploughing while removing all weedkillers. We converted all the plots of land from the first year to organic and Biodynamic cultivation.”

The soil in his Moulin-à-Vent property is shallow (less than 20 inches deep) and composed primarily of granitic sand and quartz, and about half the vines of the 35 acres were planted between 1910 and 1955. His signature wine, for this reason, is ‘Les Vieilles Vignes’—the ‘old vines.’

Thibault Liger-Belair, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Champs de Cour’ ($54)Champs de Cour is a tiny, south-facing parcel of 80 year old vines and produces a wine that typically shows its quality even when young. Harvesting is done by hand with between 40-50% left in whole bunches, following which the must is left to ferment in open vats for three weeks. Extraction is gentle and ageing is carried out in oak barrels that have seen between one and three wines for 18 months or more. The wine shows a well-balanced palate with black cherries, tar and blueberry through a chewy finish.

Thibault Liger-Belair, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Champs de Cour’ ($54)Champs de Cour is a tiny, south-facing parcel of 80 year old vines and produces a wine that typically shows its quality even when young. Harvesting is done by hand with between 40-50% left in whole bunches, following which the must is left to ferment in open vats for three weeks. Extraction is gentle and ageing is carried out in oak barrels that have seen between one and three wines for 18 months or more. The wine shows a well-balanced palate with black cherries, tar and blueberry through a chewy finish.

Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ($48)

Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ($48)

A cuvée blending nine old vine parcels of old vines located in a belt around the Moulin à Vent hill. The wine offers exotic aromas of spiced candied cherries with a rustic undertow of damp earth; bright, acidic with a firm tannic structure and long, sweet finish.

Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Centenaire’, 2015 Moulin-à-Vent ($250) en magnum

Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Centenaire’, 2015 Moulin-à-Vent ($250) en magnum

This wine originates in three distinct terroirs planted to Gamay between 1872 and 1880, pre-dating the scourge of phylloxera. One plot is the south of La Teppe, one in Les Bois Maréchaux in the north and one in Caves, to the west of the hill. Bottled only in magnums, it shows a distinctly mineral-driven nose and opens in the glass to reveal brooding dark fruit evolving into tertiary notes of forest floor and leather.

Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Centenaire’, 2014 Moulin-à-Vent ($160) en magnum

Thibault Liger-Belair ‘Centenaire’, 2014 Moulin-à-Vent ($160) en magnum

As rare as it is precise in focus, this ‘unicorn’ wine is made from vines that predate phylloxera; three distinct terroirs planted to Gamay between 1872 and 1880. One plot is the south of La Teppe, one in Les Bois Maréchaux in the north and one in Caves, to the west of the hill. 2014, as the practice, is bottled only in magnums.

Domaine de Rochegrès

Albert Bichot owns six domains in the heart of five great vinicultural regions; each estate cultivates its own land using with sustainable practices and employs a dedicated winemaking team devoted to that domain alone.

Albert Bichot, Domaine de Rochegrès

Bichot’s 13 acres within the 1631 acre Moulin-à-Vent appellation are located at the heart of one of the 18 recognized single vineyards, Rochegrès, meaning ‘grey rock’ As the name suggests, the granitic parent rock is visible at the surface of the soil in the vineyards. These vines benefit from mainly south-eastern exposure and thrive in very pure, lean pink granitic soil, forcing them to plunge their roots deep in search of the nutrients they need.

Domaine de Rochegrès, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Rochegrès’ ($48)

Domaine de Rochegrès, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Rochegrès’ ($48)

The wine, taken from the oldest vines in the Rochegrès lieu-dit, is 50% fermented in 350-liter barrels (20% new) and 50% in stainless steel vats; then 100% aged in stainless steel vats. It displays upfront notes of ripe cherry evolving toward forest bracken and dried flowers.

Domaine de Rochegrès, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ($23)

Domaine de Rochegrès, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ($23)

The wine shows a classic bouquet of smoky black cherry and blackberry followed by clove, floral notes and earth. Some weight on the palate with a pleasant, but still firm, tannic structure and fresh acidity and a long, spicy finish.

Domaine des Terres Dorées

Jean-Paul Brun

With a name from a fairy tale (‘House in the Land of the Golden Stones’), Domaine des Terres Dorées is a 150-acre vineyard located in Charnay, just north of Lyon. Owner/winemaker Jean Paul Brun is a champion of ‘old-style Beaujolais’, and by ‘old’, he means an era before pesticides and herbicides, and especially, a time when native yeasts alone were used to ferment.

Jean-Paul Brun, Domaine des Terres Dorées

He says: “Virtually all Beaujolais is now made by adding a particular strain of industrial yeast known as 71B. It’s a laboratory product made in Holland from a tomato base, and when you taste Beaujolais with banana and candy aromas, 71B is the culprit. 71B produces a beverage, but without authenticity or charm.”

Brun also insists that Beaujolais drinks best at a lower degree of alcohol and that there is no need to systematically add sugar to the must (chaptalize) to reach alcohol levels of 12 to 13%.

“My Beaujolais is made to be pleasurable,” he maintains. “Light, fruity and delicious, not an artificially inflated wine that is only meant to shine at tasting competitions.”

“The emphasis is not on weight, but on fruit,” he adds. “Beaujolais as it once was and as it should be.”

Domaine des Terres Dorées, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ($27)

Domaine des Terres Dorées, 2020 Moulin-à-Vent ($27)

This wine is exemplary of ‘old school’ Moulin; allowed the longest maceration of any Jean Paul Brun cuvées, it ages in oak for ten months. It comes from Brun’s younger vines, which are still on the order of forty years old. The wine opens with scents of berry compote, licorice, sweet soil tones and spices while offering layered and compact mid-palate with fine depth and plenty of sweet, powdery tannin.

Famille Chermette

Domaine du Vissoux

When a winemaker tries to bottle something for everyone, he/she is not always successful. The father, daughter and son team of Martine, Pierre-Marie and Jean-Etienne Chermette of Domaine du Vissoux are the exception to prove the rule, producing high quality white, red and Beaujolais rosé from crus such as Brouilly, Fleurie, Moulin-à-Vent, Saint-Amour, Crémants de Bourgogne as well as hand crafted fruit liqueurs, cassis and vine peach with ginger.

Jean-Étienne, Pierre-Marie and Martine Chermette

In 2002, Martine and Pierre-Marie Chermette acquired the La Rochelle plot in Moulin-à-Vent, a high-altitude lieu-dit with pink granitic soils and ideal south/southeast exposure. From this beautifully situated vineyard, the family wrests wines that live up to their reputation as a beacon of Beaujolais excellence, able to broadcast the region’s terroirs with authority: Old vines, diligent but traditional vinification and élevage in foudre are the rudiments of their approach.

Pierre-Marie Chermette Vissoux ‘Les Trois Roches’, 2021 Moulin-à-Vent ($33)

Pierre-Marie Chermette Vissoux ‘Les Trois Roches’, 2021 Moulin-à-Vent ($33)

Famille Chermette considers ‘The Three Rocks’ to be the ideal alliance between finesse and power. “The three different plots of vines we use for this cuvée give a wine that is full and balanced: Rochegrès give finesse, Roche Noire liveliness and fruit while La Rochelle contributes power.” The wine’s aromatic palate ranges from ripe red currants through soft pie spice and finishes with a nice mineral snap.

Domaine de la Sionnière

Estelle & Thomas Patenôtre

* Diochon is a branded Moulin-à-Vent cuvée from Domaine de la Sionnière; these wines were previously released under the Domaine Diochon label.

Along with his wife Estele, Thomas Patenôtre created the Domaine de la Sionnière in 1996, beginning with 15 vineyard acres in Romanèche-Thorins. Today, it covers more than thirty acres, with plots in some of the top Beaujolais lieux-dits, including Champ de Cour, Le Petits Morier, Les Greneriers and Les Perelles.

Estelle & Thomas Patenôtre

Moulin-à-Vent holds a place close to the Patenôtres’ heart. Says Thomas “Moulin-à-Vent stands out from other Beaujolais appellations, and the reason that some refer to it the ‘Lord of Beaujolais’ are to be sought in a glass. These are fine, complex and powerful wines with has superb aging potential, owing its intensity of exposure on the best hillsides, where the granite subsoil is rich in trace elements. Our role is to ensure that we create a harmonious balance between flavors, aromatics and tannic composition in order to obtain an authentic product. To achieve this end we pick at maximum, between the end of August and the end of September depending on the year. The grapes are then placed in vats without prior destemming in order to undergo the initial phase of carbonic maceration, characteristic of Beaujolais wines. Following this first stage, which lasts around ten days, the grapes are pressed and vatted to undergo alcoholic fermentation and malolactic fermentation. We’ll hold the wine in air-tight tanks for six to eight months before bottling.”

Domaine de la Sionnière ‘Diochon – Cuvée Vieilles Vignes’, 2021 Moulin-à-Vent ($31)

Domaine de la Sionnière ‘Diochon – Cuvée Vieilles Vignes’, 2021 Moulin-à-Vent ($31)

Crafted from vines planted in 1920, 1950 and the 1960s, it remains a benchmark of the old Diochon style, defined by well-integrated tannins without heaviness and lifted by fragrant fruit and floral aromas. The 2021 is true to this mission statement, over-performing for the vintage, filled with lush aromatics of sweet berries and plums mingled with peonies and potpourri.

Domaine de Roche-Guillon

Bruno and Valérie Copéret

With five generations working the same hillside, a certain metaphysical pas de deux takes place between terroir and wine grower. Add a third party (Bruno Copéret’s wife Valérie) and Domaine de Roche-Guillon is ready for the challenges of marketing and climate change that lie ahead. The Copéret vineyards spread over 22 rolling acres of granite-based soil; they enjoy a south facing exposure, which—combined with altitude of over 1100 feet—ensure the vines yield grapes with considerable ripeness.

Bruno and Valérie Copéret, Domaine de Roche-Guillon

Domaine de Roche-Guillon, 2021 Moulin-à-Vent ($23)

Domaine de Roche-Guillon, 2021 Moulin-à-Vent ($23)

The plots to elaborate this wine are located between the Vauxrenard commune and Émeringes, expressing the granitic soils of Vauxrenard and the sandy-clay of Émeringes. Half the selected grapes were fermented in whole bunches and half were destemmed before spending twelve days macerating at 84° F. With a floral potpourri on the nose and maraschino cherry and wild blackberry on the palate, the wine demonstrates typical muscularity of Moulin-à-Vent with gripping tannins, concentration and energy.

Beaujolais Vintage Journal

The 2021 Vintage: Chaotic Weather Allow for a Sugar/Acidity/Tannin Balance Different from Previous Sunny Years

A warm, humid winter prompted an early budbreak in Beaujolais—and that always puts growers at risk. In fact, April produced a vicious bout of frost followed by a snow-dump that affected new growth. A slight reprieve ensued in June, which allowed for a successful flowering, but heavy rain settled back in throughout July and August. The grapes did not dry out until late August, and the alert against rot and disease was a feature of the entire season.

Harvest came later than usual but was a success; the fruit remained fresh and aromatic with good acidity, although overall, 2021 wines are lighter in both body and alcohol compared to other years.

The 2020 Vintage: ‘Solar’ Vintages Continue, Round and Concentrated Wines

If you can invent a way to leave Covid out of the equation, 2020 was a wonderful vintage throughout Beaujolais. The growing season was warm, beginning with a mild and frost-free spring, which developed into a hot and sunny summer without hail or disease. Drought—a persistent worry in the region—was not as severe as it might have been, and by harvest-time the majority of grapes were in fine health with rich, ripe, almost Rhône-like flavors—raspberries, sour cherry and even garrigue; the local scrub comprised of bay, lavender, rosemary and juniper.

2020 yields were low due to the dry conditions, leading to concentrated juice and wines able to benefit from time in the cellar.

But, of course, you can’t leave Covid out of the equation: Normally the release of Beaujolais Nouveau occurs on the third Thursday of every November, but in pandemic-dominated 2020, the normal celebrations could not take place and producers instead chose to release the wines a week earlier than usual in order to allow for international shipping times.

The 2019 Vintage: The Hotter Rhône Weather Drifts North

As 2021, unexpectedly sharp April frosts cut yields throughout the region. The summer then heated up, with reports of temperature highs exceeding 104F. The ensuing drought further cut into yields, and adding insult to injury, hailstorms struck in mid-August. These storm clouds had a silver lining, however—they concentrated the juice within the fruit that remained on the vines. Although a heartbreaking loss to farmers who rely on quantity, the resulting wine is very intense with nicely balanced acids. The top estates produced cellar-worthy gems—a marvelous representation of what the appellation can offer.

Notebook …

Spoiled For Choice: More Than One Way To Make Beaujolais

The truism about the Germans and Riesling holds equal validity in Beaujolais with Gamay: They each have but a single grape, but build better wines from it than anyone else on earth. This is not to suggest that Beaujolais and its ten fascinating Grand Crus are homogenous—the opposite is true. Each region, each climat and each winemaker provides slight variations in terroir and technique.

Nowhere does the dual nature of Beaujolais appear more profoundly than in the choice faced by winemakers to vinify in the traditional ‘Burgundian’ way, or to rely on the semi-carbonic macerations that produce the fruity, ridiculously early-drinking Nouveau-style wines. Both techniques have their place in Beaujolais, and both produce strikingly different flavor profiles.

Traditional Burgundian-style production relies on destalking and crushing the grapes prior to fermentation, a mean of opening up the fruit up and bringing out the tannins. Only then does fermentation start, either through natural yeasts on the grape skins or from a commercial additive. In most cases, wines made this way in Beaujolais will also have wood aging. Alternately, semi-carbonic maceration involves fermentation that starts in closed containers. The wine is then transferred to traditional fermentation vats and yeast is added to continue the process. While some of the wines will go into wood, many will continue to age in tanks, which highlight the fruit and lower the tannins.

Moulin-à-Vent is Capable of Long-Aging, Pleasurable While Young

‘Decanter Magazine’ recently staged a vertical tasting of Château du Moulin-à-Vent, vintages 2010-2019 (and published in the July 2022 issue), believing that the revitalization of the estate by the father-and-son team of Jean-Jacques and Édouard Parinet (and their brilliant winemaker Brice Laffond) has been so successful that they were willing to give Master of Wine Andy Howard a crack at determining if all the hype around the ageability of Moulin-à-Vent is warranted. Wines from 1996 and 1976 were also tasted.

No cliffhangers here: Howard MW’s opinion was a resounding ‘yes’.

As most Beaujolais fans know, the wines of the ten Crus of Beaujolais can be among the world’s most terroir-expressive. Subtle shifts in sun exposure and soil structure from commune to commune can be detected in the glass, even among those with untrained palates. The wines from Château du Moulin-à-Vent are traditional standouts for their robust texture, deep flavor and age-worthiness made possible by Jacques and Édouard Parinet’s adherence to Burgundian winemaking methods and their steadfast refusal to employ semi-carbonic maceration. Because of that, their wines reveal the best of Beaujolais’ most powerful Cru, the wind-funnel slopes of Moulin-à-Vent.

According to Howard MW: “The tasting certainly demonstrated a distinct shift in style with the change in oak management. Whereas the older vintages (although with undoubted aging potential) demonstrated a firmer tannic structure, the more recent vintages were much more expressive, floral, delicate and refined. However, there is every reason to suspect that these wines will deliver the same ageing capacity as the more ‘traditional’ style.”

- - -

Posted on 2025.02.01 in France, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

The Champagne Society February 2025 Selection: Pascal Lejeune

Champagne Pascal Lejeune’s Terroir Fundamentals

Preserving a Place’s Details and a Vine’s Finger Print in a Single Premier Cru Village

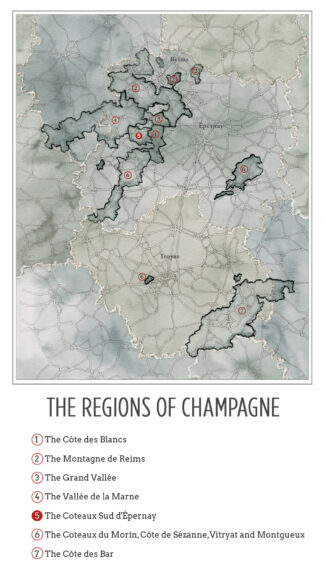

The Coteaux Sud d’Épernay

Premier Cru Pierry In Two Bottles ($103)

Champagne Pascal Lejeune ‘N°4 – OXYMORE’ Blanc de Noirs (100% Meunier) Brut

and

Champagne Pascal Lejeune ‘N°2 – ANAPHORE’ Premier Cru Pierry Blanc de Blancs (100% Chardonnay) Extra-Brut

Dear Member,

Dear Member,

The soul of Champagne has always been finesse, and a Cellar Master’s decision to balance blends (in a search for complementary aromas and personalities) or to bottle a single variety is intended to be a statement. Listening to the winemaker’s voice in different incarnations of the same art form is to enjoy an ever-changing dialogue between man and grape.

It’s our normal practice to send out a single bottle as a bimonthly presentation, but this month, it will be two—one Blanc de Blancs and one Blanc de Noirs—from Champagne Pascal Lejeune. Taste them individually or side-by-side; each is a unique reflection of Pascal and Sandrine Lejeune’s commitment to terroir expression through organic cultivation.

Listen to the conversation with your nose and palate and decide which one resonates best with your personality.

Elie

The permutations of Champagne are as varied as its terroir, but in the exploration, facts keep popping up in triads: In the favored grapes (Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Meunier), in styles (Blanc de Noirs, Blanc de Blancs, Rosé) and in varying level, in dosage (Brut, Sec and Doux). There are strata in each of these categories, of course, but you get the picture.

Now the trio of Pascal, Sandrine and Thibaut Lejeune (a dad, mom and son team) from the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay, are excelling in the production wines from three categories: Village level, lieu-dit (monoparcellaire) level and a cépage made of grapes from the three villages where they grow fruit, Épernay, Moussy and Vinay.

A new addition to our Champagne portfolio, Champagne Pascal Lejeune is a small grower/bottler whose reputation is as solid as the output is small. These wines represent both a spirit of renewability in an age-old product and some of the most terroir-reflective Champagnes we’ve tasted.

The Coteaux Sud d’Épernay: Middle Grounds

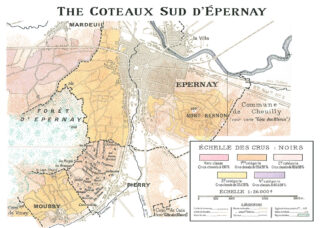

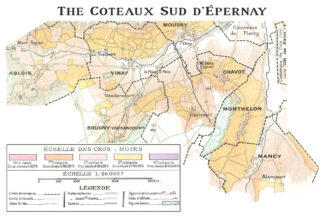

The Reims-based Union de Maisons de Champagne names 17 ‘terroirs’ in Champagne; among them, on the left bank of the Marne river, is Côteaux Sud d’Épernay. As the name suggests, it occupies the slopes (côteaux) south of Épernay. These slopes are formed by three streams (another triad), Le Cubry, Le Darcy, and Le Mancy. Le Cubry empties into the Marne at Épernay, and forms the valley that runs to the southwest and further west to Saint-Martin-d’Ablois. Le Darcy is a tributary of Le Cubry that empties into the latter at Pierry and Le Mancy is a tributary of Le Darcy that empties into it in the northern part of the Mancy commune.

Enough geography? On to grapes! The Coteaux Sud d’Épernay is fairly evenly balanced between Meunier at 46.7% and Chardonnay at 40.9%, with Pinot Noir making up the remainder. Somewhat simplified, it can be said that Chardonnay is most common in Épernay and in the valleys of Le Mancy and Le Darcy in the north and east, while Meunier prevails in the valley of Le Cubry (excluding Épernay) in the center and west.

Sandwiched between two powerhouse wine regions (Côte des Blancs and Vallée de la Marne), the Coteaux has an identity removed from either one. Its terroir is different from the clay-heavy soils of the Marne and it lacks the pure chalk that puts the ‘blanc’ in the Côte des Blancs.

In short, these Champagnes are uniquely situated to offer the best of both worlds. As a result, the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay has long fought for recognition as entity unto itself, not necessarily a sub-region of its big brothers on either side.

The current vineyard surface in the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay is a little over 3000 acres distributed among 878 vineyard owners in 11 communes.

Champagne Pascal Lejeune

Beating swords into ploughshares is a Biblical injection that Pascal Lejeune takes literally—he left his career in the military and gave himself to the vine. It didn’t hurt that he fell in love with a Champagne grower’s daughter: Pascal’s wife Sandrine hails from a family that has been growing grapevines in Moussy (where more than half of the vineyard’s grapevines are located) on the south-facing slopes of Épernay since 1910. Originally a side operation, not an essential part of the family’s activities, Sandrine’s great grandfather Edmond played an active part in creating the Moussy cooperative.

In 1995, when Pascal and Sandrine took the reins, their aim was to usher in a new era by enlarging the vineyard area into nearby terroirs, and by enriching the range of offerings via new cuvées: As a brand, Champagne Pascal Lejeune was born.

Pascal and Sandrine Lejeune, Champagne Pascal Lejeune

Says Pascal, “I believe I have a responsibility and commit myself collectively to our business and our terroir in order to perpetuate and monitor developments for our children and future generations. This requires a sincere respect for people, nature, our vines, our soils, and careful work in order to obtain quality grapes. To offer you the best that nature offers us, our vintages are very different, there is something for every occasion and taste… Nature does things well!”

This commitment to nature has been proven out over the past 17 years; Lejeune was one of the first producers in Champagne to plant specially-selected grass species between vine rows. Manual techniques are used for pruning, trellising and debudding. “The benefits of this special care can be observed,” says Sandrine. “Biodiversity is maintained, the soils are protected, the erosion is limited, and as the grapevine roots develop, the phytosanitary products have been significantly reduced.

Pascal adds: “Our aim is to give our soils the utmost respect in order to express the organoleptic qualities with authenticity and reveal the subtlety of our champagne. The culmination of these special treatments is, strictly speaking, the grape harvest, which is carried out entirely by hand, reflecting an entire year’s labor of love.”

Pascal and Sandrine are happy with the latest addition to their team, their son Thibaut, now a fifth-generation wine-grower, who joined the family business in 2015. Having completed his oenology and BAC qualification, he shares his father’s passion for grapevines and brings a fresh perspective to the family adventure, and offers a perspective on what he has taken on:

“Our three grape varieties spread out across a mosaic of 42 plots, 64% of our vines are Meunier. Otherwise, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir represent respectively 25% and 11% of the whole vineyard.”

Single-Village Expression: The Stony Soils of Premier Cru ‘Pierry’

The Premier Cru village of Pierry is located immediately to the south of Épernay at the foot of southeast-facing slopes where the vineyards are located. The stream Le Cubry, which forms the valley runs just below the village and continues to the west, emptying into the Marne River at Épernay. Within Pierry, single vineyard sites include Cantuel, Les Chevernets, Les Gayères, Les Gouttes d’Or, Les Noues, Les Porgeons, Les Rouges Fosses, and Les Tartières.

In the now-defunct ‘échelles des crus’ system, Pierry’s former rating of 90% makes it a Premier Cru village, the only commune in the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay to be so classified. (Its three neighbouring communes in the same area were rated 88%.) The terroir explains it, and a local saying is, “Pierry est Pierreux…” Pierry is stony, dominated by flint and chalk, and this minerality carries through to the wine.

Pierry’s current vineyard surface is 270 acres; half Meunier, 32% Chardonnay and 18% Pinot Noir. There are 125 vineyard owners in the commune.

nv Champagne Pascal Lejeune ‘Figure de Style N°4 – OXYMORE’ Brut ($49)

nv Champagne Pascal Lejeune ‘Figure de Style N°4 – OXYMORE’ Brut ($49)

100% Meunier, 40% from the 2019 harvest, 60% reserve wine from 2018; the wine undergoes partial malolactic and 30% barrel aging with regular lees stirring. Dosage is to Extra-Brut level; 6 gram/liter. The wine is plump and bold with rich notes of raspberry and stone fruit underlined by cassia and clove, all characteristics of the Meunier grape. 1255 bottles made. Disgorged July 2023.

Chardonnay in Pierry

Less than 30% of Champagne’s 84,000 low, densely-planted acres are Chardonnay, the grape that lords of Burgundian white wine. In cool climates north of Burgundy, however, Chardonnay demands well-favored sites and thrives best on the south- and east-facing chalky slopes of the Côte des Blancs south of Épernay.

nv Champagne Pascal Lejeune ‘Figure de Style N°2 – ANAPHORE’ Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut ($54)

nv Champagne Pascal Lejeune ‘Figure de Style N°2 – ANAPHORE’ Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut ($54)

100% Chardonnay, all from the 2020 harvest; the wine ages in 30% oak barrels for ten months with regular stirring of lees. Dosage is to the level of Extra-Brut, 4 gram/liter, using homemade liquor distilled from the three grape varieties used in Champagne. The wine displays complex aromas of lime, sweet Meyer lemon and golden apple. 1235 bottles made. Disgorged February 2024. 2900 bottles produced.

Site-Specific ‘Parcellaire’: Village Vinay’s Lieu-dit ‘Les Longs Martins’

The vineyards of Vinay in the Vallée de la Marne, are located both on the slope southwest of Épernay formed by the valley of the stream Le Cubry, and also, in part, below the slope. The vineyards face south-south east, and Meunier is the most common grape variety found. The vineyards are continuous with those in Moussy and Saint-Martin-d’Ablois. The 365 acres are owned by 102 individual ‘exploitants.’

A ‘parcel’ is site-specific, synonymous with ‘lieu-dit’ as used in Burgundy—a named group of exceptionally emblematic vine. It is estimated that there are 84,000 of these named parcels throughout Champagne. ‘Les Longs Martins’ is one.

nv Champagne Pascal Lejeune ‘Figure de Style N°6 – ANALOGIE’ Rosé de Saignée Zéro Dosage ($74)

nv Champagne Pascal Lejeune ‘Figure de Style N°6 – ANALOGIE’ Rosé de Saignée Zéro Dosage ($74)

From the organic lieu-dit ‘Les Longs Martins’, this saignée is 100% Pinot Noir (2019 harvest) from vines that average 25 years old grown in clay, silt, sand and marne limestone. Maceration lasted ten hours, and no malolactic fermentation occurred, leaving the crisp acids intact along with notes of brioche, sweet pastry, vanilla, ripe forest berries and raspberry coulis. Only 638 bottles made. Disgorged December 2022.

The Bigger Picture: Villages Vinay, Moussy and Épernay

Of the 18 communes in the canton ‘Épernay-2’, the triad that produces grapes for Style N°1 each brings its own special spice to the party.

nv Champagne Pascal Lejeune ‘Figure de Style N°1 – METONYMIE’ Extra-Brut ($42)

nv Champagne Pascal Lejeune ‘Figure de Style N°1 – METONYMIE’ Extra-Brut ($42)

59% Meunier, 32% Chardonnay, 9% Pinot noir from vines that average thirty years old and grown on a south-southeast exposure. 40% of the harvest in this wine came from 2019, the rest from 2018; malolactic only touches the 2019. These grapes originate in the three communes of Vinay, Moussy and Épernay and provide beautifully focused aromas of apple, caramel, stones and minerals. 13,875 bottles made. Disgorged July 2023 and dosed at 4 gram/liter.

Notebook ….

Single Harvest vs. Vintage

In France, under Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) rules, vintage Champagnes must be aged for three years—more than twice the required aging time for NV Champagne. The additional years on the yeast is said to add complexity and texture to the finished wine, and the price commanded by Vintage Champagne may in part be accounted for by the cellar space the wine takes up while aging.

On the other hand, a Champagne maker might prefer to release wine from a single vintage without the aging requirement; the freshness inherent in non-vintage Champagnes is one of its effervescent highlights. In this case, the wine label may announce the year, but the Champagne itself is referred to as ‘Single Harvest’ rather than ‘Vintage’.

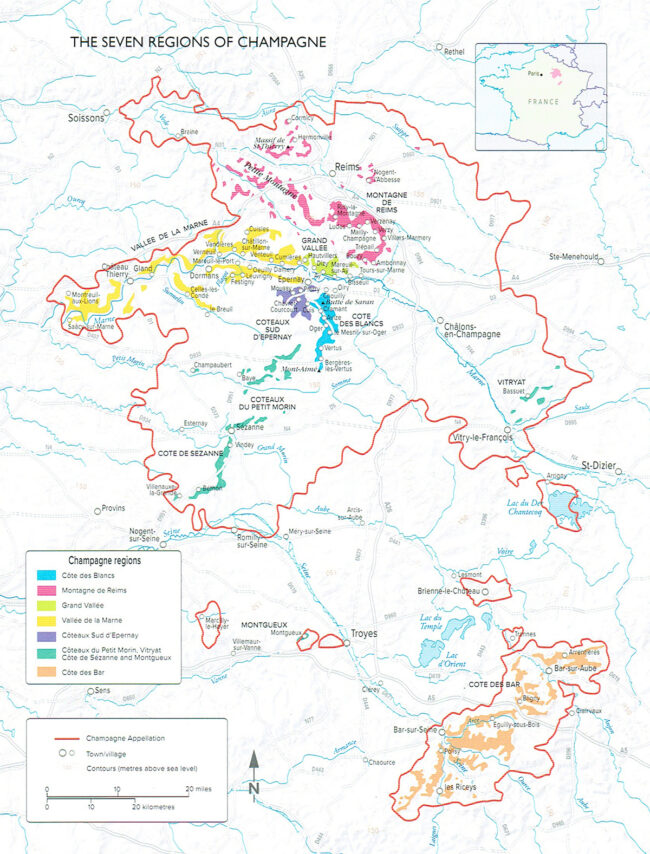

Drawing the Boundaries of the Champagne Region

To be Champagne is to be an aristocrat. Your origins may be humble and your feet may be in the dirt; your hands are scarred from pruning and your back aches from moving barrels. But your head is always in the stars.

As such, the struggle to preserve its identity has been at the heart of Champagne’s self-confidence. Although the Champagne controlled designation of origin (AOC) wasn’t recognized until 1936, defense of the designation by its producers goes back much further. Since the first bubble burst in the first glass of sparkling wine in Hautvillers Abbey, producers in Champagne have maintained that their terroirs are unique to the region and any other wine that bears the name is a pretender to their effervescent throne.

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

The lauded wine writer Peter Liem expands the number of sub-regions from four to seven, dividing the Vallée de la Marne into the Grand Vallée and the Vallée de la Marne; adding the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay and combining the disparate zones between the heart of Champagne and Côte de Bar into a single sub-zone.

Courtesy of Wine Scholar Guild

Lying beyond even Liem’s overview is a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that compliment or contrast when final cuvées are created.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Épernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

… Yet another reason why this tiny slice of northern France, a mere 132 square miles, remains both elite and precious.

- - -

Posted on in France, Saturday Sips Review Club, The Champagne Society, Champagne | Read more...

Châteauneuf-du-Pape Finds Its Balance: Neo-traditionalist Isabel Ferrando Makes the Case for Blending (or not Blending) Terroir & Varieties. Pack $499

In-Store Tasting with Guillemette Ferrando, Famille Isabel Ferrando

Saturday Sips, January 18 from 1 pm to 3 pm

This Saturday, January 18, from 1pm to 3pm, we are excited to welcome Guillemette Ferrando, daughter of iconic, iconoclastic winemaker Isabel Ferrando for an in-house tasting of the wines of Famille Isabel Ferrando. Guillemette will walk us through technique and philosophy, illustrating the evolution of Châteauneuf-du-Pape and her mother’s journey from a high-powered banker to a dynamic vigneron in beautiful Southern Rhône. Isabel’s expressions of Châteauneuf-du-Pape are as unique as they are profound, and Guillemette has inherited a pioneering spirit and adaptability in and out of the vineyard.

Elie

Isabel Ferrando and daughter Guillemette

Isabel Ferrando comes from a small town about a half an hour south of Châteauneuf-du-Pape. To the hidebound traditionalists in Southern Rhône’s most heralded appellation, that means she is an outsider. Perhaps if you want to bring something new to the party, it helps if you weren’t invited to the party in the first place.

In any case, since launching Domaine Saint-Préfert in the early years of this century, drawing from a 33 acre parcel she purchased from the Serre family, her wines have earned some of the highest praise in France. Critics have trumpeted her wines as being not only among the most profound in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, but in the world.

And to her everlasting credit, Ferrando has managed to wrest many of these gems from a parcel that is considered among the most heat-prone in the region.

Her reputation has grown in each year of the two decades since her first release in 2003, but this has not stopped her from constant innovation, introspection and improvement. She was certified biodynamic in 2022, the same year she opened a new winery (built from local Luberon stones) with an assortment of cement vats for primary fermentations and blending. In the cellar, Ferrando works primarily with neutral demi-muids, but she has also introduced glass demi-johns, Stockinger foudres, and amphora. Aging in the correct vessel for the style and variety has become a cornerstone of her technique.

She says, “Under the benevolent and demanding eye of Henri Bonneau, the maestro, I learned that work in a vineyard must be progressive, from the slow taming of the vines to the translation of the grapes into wine. Inspired by the tradition of Burgundy’s climats, I first produced three cuvées from the Saint Préfert terroirs from 2003 to 2019: Classique, Réserve Auguste Favier and Collection Charles Giraud. Then, the Grand vin du terroir de Saint Préfert was created in 2020, the ultimate result of 20 years of work.”

The Terroir of Châteauneuf-du-Pape: A Mosaic of Soils

Châteauneuf-du-Pape in France’s Rhône valley has traditionally been viewed as a rustic cousin to the elegant and long-lived persistence of great wines from Bordeaux and Burgundy. Châteauneuf is age-worthy, certainly, but there is exuberance in the fresh fruit flavors that dominate the style that makes it decadently drinkable virtually from the day it is released. It was said to make up for in pleasure what it lacked in sophistication.

With more than 8,000 acres under vine, Châteauneuf-du-Pape is the largest appellation in the Rhône, producing only two wines, red Châteauneuf-du-Pape, representing 94% of the appellation’s output, and white Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Of the eight red varietals planted, Grenache is the most dominant variety by far, taking up 80% of vineyard space, followed by Syrah, Mourvèdre and tiny quantities of Cinsault, Muscardin, Counoise, Vaccarèse and Terret Noir.

Terroir varies and can only be viewed as a generalization; limestone soil predominates in the western part of Châteauneuf-du-Pape; sand and clay soil covered with large stones on the plateaus. Mixed sand, red and grey clay, and limestone can be found in the northern part of the appellation, less stony soil alternating with marl in the east and shallow sand and clay soil on a well-drained layer of gravel in the south. The large pebbles contribute to the quality of the vines and grapes by storing heat during the day and holding water.

Like the soils, there is an enormous diversity of winemaking styles among CdP producers, creating both appealing, easy-to-understand fruit-filled wines as well as wines of greater intensity and sophistication.

Untrained Old Vines Grenache Bush in Galets Roulés

Grès Rouge, Sand and Safre

Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s New Old-Style

Throughout much of its history, CdP provided a leathery foil to the potent and somewhat austere elegance of Bordeaux and the heady sensuousness of Burgundy. CdP is ‘southern wine’, filled with rustic complexity—brawny, earthy and beautiful. But as a business, all wine finds itself beholden to trends, since moving product is necessary to remain afloat. During the Dark Ages (roughly1990 through 2010—in part influenced by the preferences of powerful critic Robert Parker Jr.) much of Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s output became bandwagon wines, jammy and alcoholic, lacking structure and tannin, in the process becoming more polished than rustic and more lush than nuanced. For some, this was delightful; for others, it was a betrayal of heritage and terroir.

These days, a new generation of winemakers seem to have identified the problem and corrected it. Recent vintages have seen the re-emergence of the classic, balanced style Châteauneuf-du-Pape, albeit at slightly higher prices. A changing climate has also altered traditional blends, so that more Mourvèdre may be found in cuvées that were once nearly all Grenache. Mourvèdre tends to have less sugar and so, produces wine that is less alcoholic and jammy, adding back some of the herbal qualities once so highly prized in the appellation. But a return to old school technique has also helped; however, many of the wines in this offer were destemmed prior to crushing and were fermented on native yeast rather than cultured yeast.

The Primacy of Place: Blending Terroirs Changes its Role

Terroir has always been lauded as a reflection of place while blending is a means for a winemaker to reflect an interpretation of places. When a wine is released as a monovarietal from a labeled lieu-dit, the expectation is that its character will express primacy—all the specific complexities of a specific soil structure and exposure-driven weather conditions over a single season.

When a wine is released as a blend, both of grape varieties and vineyards, the paradigm shifts and the goal—born of practicality, tradition or artistic license—is to showcase a final product built from various ingredients, as a chef might conceive a course. Likewise, a choral group does not seek to drown out potential soloists, but to use each voice to its strength. An ensemble of terroirs is a search for harmony. It does not try to overpower individual terroirs, but the opposite: It attempts weave them together to create a tapestry that illustrates the totality of a concept.

Rare is the winemaker who not only appreciates, but excels under both philosophies. So it is fitting that Isabel Ferrando has situated herself in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, where blending wines is the foundation of tradition. In 2020, Ferrando—having studied her parcels for many years—decided to explore the idea of blends. She says, “18 years of experience and knowledge of the terroirs and grape varieties now allow me to return to the great tradition of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, so I have released single blended wine in Châteauneuf-du-Pape red and white. …because the history of this appellation is written in this great art.”

Famille Isabel Ferrando

The ‘Grand Vin du Terroir de Saint Préfert’

If a ‘Grenachiste’ is a loyalist who fights for Grenache, it would be hard to find a High Priestess more qualified than Isabel Ferrando. A former banker who learned winemaking at Domaine Raspail-Ay in Gigondas, she purchased the seventy-year old Domaine Saint-Préfert from the Serre family (one of the region’s first domains to estate bottle) in 2002. That year, the property stood at a little over thirty acres, all in the Les Serres lieu-dit south of the village of Châteauneuf.

Les Serres has a much longer history: In the 1920’s, a pharmacist from Avignon named Fernand Serre purchased a vineyard parcel south of Chateauneuf du Pape, drawn to the spot by coincidence of the name: Les Serres. When Ferrando purchased the lieu-dit, she found vines more than a hundred years old. Alas, many were unsalvageable, and some places needed to be replanted entirely.

Isabel Ferrando

Once a successful first vintage was in the cellar, Ferrando began to purchase more land in the appellation, expanding her holdings to its current 55 acres. Among her acquisitions was a small parcel of old-vine Grenache vines that became Domaine Ferrando ‘Colombis’. Meanwhile, in 2013, Domaine Saint Préfert earned its certification for using 100% biodynamic farming, an agricultural technique that is somewhat easier pull off in Châteauneuf thanks to the sporadic but predictable Mistral winds that naturally protect vines from pests and mildew.

Still, it is Ferrando’s ever-growing expertise and hands-on winemaking that produces her outstanding portfolio. Says ‘The Grenachiste’: “There is no secret formula to making great wines in Châteauneuf. I work with a young team who is always open to new ideas. We rely on tradition without being trapped by it, working with whole-cluster fermentations without added yeasts because we discovered that it increased freshness in the wines and lowered alcohol, giving the wines vibrancy. Aging occurs in a mix of concrete and used foudres for up to 18 months.”

Isabel maintains that her responsibility is to strive for constant innovation to propel the estate forward. She believes that ‘innovation today is the innovation of yesterday.’ It is what led her to embrace biodynamic farming and it is what led her to build her new winery with only materials from within or surrounding her vineyards: It is what led Isabel to re-embrace the DNA of Chateauneuf-du-Pape and focus on the singular blended wine to showcase the best of the vintage.

* It is noted that with the arrival of Isabel Ferrando’s daughter Guillemette to the winemaking team in 2020, Isabel Ferrando has bottled her wines under the name ‘Famille Isabel Ferrando’ and totally changed the range previously labelled as Domaine Saint-Préfert.

Instead of an extensive portfolio of single-vineyard bottlings, she has combined most of her fruit (formerly bottled as ‘Classique,’ ‘Reserve Auguste Favier’ and ‘Collection Charles Giraud’) into a new flagship cuvée.

Latest Release: Special Pre-Arrival 6-Bottle Sampler Pack $499

We are proud to offer our family of customers a specially priced Famille Isabel Ferrando pre-arrival pack that includes one bottle each of Ferrando’s Châteauneuf-du-Pape (red) 2022 and white (2023) with one bottle of the special ‘Colombis’ cuvée in addition to three bottles of Famille Isabel Ferrando’s Côtes du Rhône ‘Beatus Ille’ 2023.

Côtes du Rhône ‘Beatus Ille’: The Gateway to Châteauneuf-du-Pape

The storied River Rhône runs through southern France from its bed in the south of the Drôme, flowing between vineyards and ancient edifices all the way to the sea. Only a small portion of it wends through the vineyards that have become its most renowned, those of Châteauneuf-du-Pape—a village you can drive through faster than you can pronounce its name. Surrounding it are the other, less flashy, less famous and less pricy vines of the Côtes du Rhône.

‘Beatus Ille’ is a quote from an ancient poem by Horace in the second Epode; it translates to ‘happy is the man,’ and may well be the mood of those who first smell the sea and wild herbs of the Provence. Ferrando chose this name to reflect the spirit of the wine, which she refers to as, “A wine of great freedom, expressing the pleasure of living in the country surrounded by good food and true friends. Beatus Ille is a cup of fresh fruit that is greedy, complex and uninhibited.”

2020 Domaine Saint Préfert ‘Clos Beatus Ille’, Côtes du Rhône ($31)

2020 Domaine Saint Préfert ‘Clos Beatus Ille’, Côtes du Rhône ($31)

90% grenache, 5% Syrah, 5% Cinsault from a parcel named ‘La Lionne’ in the Sorgues district just at the southern border of Chateauneuf-du-Pape where the soil is a blend of red clay and pebbles. It’s 100% destemmed and fermented and aged in cement tanks. It shows loads of fresh summer fruit with a touch of Provençal herbs and a hint of peppery spice behind nicely integrated tannins.

2023 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Beatus Ille’, Côtes du Rhône (PRE-ARRIVAL $33) Package $499

2023 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Beatus Ille’, Côtes du Rhône (PRE-ARRIVAL $33) Package $499

Ferrando’s 2023 release of ‘Beatus Ille’ takes advantage of the vintage’s aggressive warmth to produce a bottling full of explosive and opulent fruit peppered with the region’s classic garrigue.

.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape ‘Classic’: Post Parcellar Exploration

Wine evolves and so do winemakers. When the two are in tandem, the results can be unparalleled. That is certainly the case with Isabel Ferrando’s re-interpretation of her mission in CdP.

Of course, the concept of evolution may apply to an entire appellation, and nowhere is the relatively rapid rise, fall, and rebirth of a style more evident than in Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Throughout much of its history, CdP proved to be a leathery foil to the potent and somewhat austere elegance of Bordeaux and the heady sensuousness of Burgundy. They were considered ‘southern wines’ of rustic complexity—brawny, earthy and beautiful.

But as a business, wine finds itself beholden to trends, since moving product is necessary to remain afloat. Suring the Dark Ages (roughly1990 through 2010—in part influenced by the preferences of powerful critic Robert Parker Jr.) much of Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s output became bandwagon wines, jammy and alcoholic, lacking structure and tannin, in the process becoming more polished than rustic, more lush than nuanced. For some, this was delightful; for others, it was a betrayal of heritage and terroir.

Isabel Ferrando seems to have identified the problem and corrected it. Her take on the classic, balanced style Châteauneuf-du-Pape is aided by a changing climate has also altered traditional blends, so that more Mourvèdre may be found in cuvées that were once nearly all Grenache. Mourvèdre tends to have less sugar, and so produces wine less alcoholic and jammy, adding back some of the herbal qualities once so highly prized in the appellation. But a return to old school technique has also helped.

If you survived the Fruit-Bomb era begrudgingly, you will no doubt welcome the return to the future that has begun to again take hold in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, in many ways, completing a cycle.

2020 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($114)

2020 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($114)

2020 was the year that Isabel Ferrando put her poetry in motion, creating a cuvée of 75% old-vine Grenache, 12% Cinsault, 11% Mourvèdre, and 2% Syrah drawn entirely from the Les Serres parcel, the oldest vines she owns. This was the fruit previously used to make up her Favier and Giraud wines. 100% whole cluster made in demi-muids; the wine shows polished oak spice and toasty cedar encasing warm blackberry compote, fig and red currant. The wine is incredibly concentrated with suave tannins on a long, mocha-dusted finish.

2021 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($114)

2021 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($114)

The 2021 vintage offered more problems than 2020, with late and devastating frosts. Old vines such as Ferrando farms did far better than younger vines.

* A more detailed analysis of Vintage 2021 is offered below.

2022 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape (PRE-ARRIVAL $107) Package $499

2022 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape (PRE-ARRIVAL $107) Package $499

“The 2022 vintage is an exceptional one for Châteauneuf-du-Pape in general and for us in particular. For me, it also marks a significant milestone in my work. I have rarely felt as accomplished and proud of a vintage in my career.” – Isabel Ferrando

* A more detailed analysis of Vintage 2022 is offered below

White Châteauneuf-du-Pape: Two Parcels, Two Varieties.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape Blanc is one of the most consistently under-rated and under-celebrated wines in an occasionally over-rated pantheon of red CdPs. Always a sensuous mouthful, the warm weather tends to ripen white varietals (generally a measured blend of Grenache Blanc, Roussanne, Clairette and/or Bourboulenc) to a tropical cornucopia. It’s this juicy explosion of exotic flavors that make the style delightful in its youth and increasingly complex with age, picking up meaty notes of leather and white truffles.

Isabel Ferrando focuses on old-vine Clairette and Roussanne from two plots in her Serres lieu-dit, using Clairette to bring minerality and the region’s characteristic salinity while the Roussanne provides honeysuckle, acacia flower and peach notes to a tannic backbone.

She began making this wine in 2009 after sharing a bottle of after 1947 Bonneau at a meal with her mentor, Henri Bonneau, the last of that vintage of old vine Clairette—grapes that still grew on her property.

2021 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape Blanc ($114)

2021 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape Blanc ($114)

“This wine is vinified in glass globes and in foudres,” says Isabel Ferrando. “The purity and freshness conferred by fermentation in glass and the tension offered by the 12 HL oak foudres ensure a great capacity for ageing. The organic and biodynamic management allows us to achieve the right level of maturity without excessive alcohol and with remarkable natural acidity.”

60% Clairette and 40% Roussanne the wine shows acacia and lime blossom on the nose with jasmine, rosehip and pulpy mango and pineapple leading to a needle-sharp and focused finish.

2022 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape Blanc ($114)

2022 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape Blanc ($114)

* From Ferrando’s favorite vintage—more details are given below.

.

2023 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape Blanc (PRE-ARRIVAL $107) Package $499

2023 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape Blanc (PRE-ARRIVAL $107) Package $499

* Specifics of the 2023 vintage are offered below.

White Châteauneuf-du-Pape en Magnum: Rich, Rare and Age-Worthy Monovarietal

Why the magnum? Surface area plays a tremendous role in the changes that a wine undergoes during élevage and later, ‘en bouteille’, and these changes happen at a rate that is in proportion to the size of the container. In a magnum—roughly twice the size of a conventional wine bottle—the aging process is slowed down and the wine will keep fresher longer; a plus if the wine is white.

Back in 2009, Henri Bonneau assured Ferrando that she had the ability and grapes to make a wine to rival his own from the rare, old-vine, pink Clairette that is co-planted in her vineyards. The first year, Bonneau helped to do the vinification. It was Bonneau who told her, “You are who you are; embrace the wines that naturally come from your style. Go with what nature give you. Less is more.”

The wine is very gently pressed and aged for 18 months in one new large barrel. Bonneau recommended bottling it in magnum-size because there is not enough for everyone, so when it’s opened, it’s for a special occasion.

To this day, Ferrando’s tradition is to always give the first bottle each vintage to the Bonneau family. Normally, only one 600-liter barrel is made per year.

2021 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Vieilles Clairettes, Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($399) (1.5 Liter)

2021 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Vieilles Clairettes, Saint Préfert’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($399) (1.5 Liter)

Only produced ‘en magnum’, this is a heavily allocated gem with less than a thousand bottles made and even fewer exported. 100% Clairette from 100-year-old vines in the dry-farmed lieu-dit ‘Quartier des Serre’ renowned for being one of the most sun-drenched plots in the appellation as well as nurturing vines in well-drained, river-rolled pebble soil. An exquisite, unctuous expression of an under-appreciated varietal, the wine reflects both sun and sand with warm notes of honey, quince jam, creamy lemon curd and pink grapefruit acidity as a backbone.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape ‘Colombis’: Grenache, Reconsidered.

Despite its potential for splendor in the glass, Grenache has never made the leap into the rarified atmosphere of the ‘noble’ grapes. But in the right hands, grown in the proper lieu-dit and farmed correctly, it can be as expressive of terroir as Pinot Noir and as complex and age-worthy as Cabernet Sauvignon. In Châteauneuf-du-Pape, it produces most favorably on sandy soils that provide delicacy and finesse, but where there is also limestone for structure, red clay for the development of rich (but not harsh) tannins and the small stones known as ‘galets’ for power.

For a grape that produces such bold and muscular wines, Grenache is thin-skinned and not overly acidic, so it must be picked at an optimum period of phenolic ripeness to avoid becoming flabby and aggressively alcoholic. Vine age is of extreme importance for Grenache, with younger cultivars making pale-colored and often mediocre wines—60-100 years appears to be an ideal age for producing wine of consistently good quality.

2016 Domaine Isabel Ferrando ‘Colombis’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($172)

2016 Domaine Isabel Ferrando ‘Colombis’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($172)

‘Colombis’ is 100% Grenache, but a blend from three parcels in the western part of the appellation: Colombis, featuring sandy soils, Les Roues, where clay lies just beneath the surface, and Le Cristia, where sand again predominates.

2017 Domaine Isabel Ferrando ‘Colombis’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($172)

2017 Domaine Isabel Ferrando ‘Colombis’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($172)

100% old-vine Grenache from Ferrando’s prized vineyards.

* An overview of the 2017 vintage is found below.

2019 Domaine Isabel Ferrando ‘Colombis’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($155)

2019 Domaine Isabel Ferrando ‘Colombis’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($155)

The vines average 60 years and the concentrated juice from the small clusters produce a wine that critic Jeb Dunnuck referred to as “One of my favorite wines in the world.” Expansive in bouquet and again on the palate, the wine shows spice-accented currant preserves with incense and cola, crisp mineral undertones and an intensely long finish framed by velvety, well-integrated tannins.

2021 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Colombis’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($199)

2021 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Colombis’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($199)

* An overview of the 2021 vintage is found below.

2022 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Colombis’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape (PRE-ARRIVAL $186) Package $499

2022 Famille Isabel Ferrando ‘Colombis’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape (PRE-ARRIVAL $186) Package $499

Isabel Ferrando affixed her own name to the mono-varietal wines she produced at Domaine Préfert before the change to ‘Famille Isabel Ferrando.’.

* An overview of the 2022 vintage is found below.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape ‘F601’: Pure Cinsault, Pure Audacity

The roughly 51,000 acres of Cinsault in France make it the ninth-most-planted grape there, but that is just a fraction of the more than 120,000 acres that covered wine country during its peak years in the 1970s. Now, while much of the production is still used in red blends, an increasingly large share of this acreage goes into the region’s many rosés.

In Châteauneuf, it doesn’t even come in third, landing behind Grenache, Syrah and Mourvèdre in acres planted. Still, it produces copious yields and thrives in drought conditions, ripening roughly one-third of the way through the harvest cycle. For Isabel Ferrando, who inherited supremely old Cinsault vines, it is a variety worth romancing, and she pushes it front and center in her unique and luscious ‘F601.’

2018 Domaine Isabel Ferrando ‘F601’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($786)

2018 Domaine Isabel Ferrando ‘F601’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($786)

‘F601’ may sound like an unpoetic name for a lieu-dit, and in fact, it is an arid block in the southern part of the estate. It is also atypical of the terroirs of Châteauneuf-du-Pape; fifteen feet below the surface, sand made of degraded quartz can be found and a bit higher up, extra moisture is lodged in a fine layer of blue clay fed by the mica gravel and rolled pebbles already visible at ground level. Of this remarkable habitat for Cinsault, Isabel Ferrando writes, “I needed 16 years of observation and apprenticeship to find the audacity to throw away the rule book and forge a personal relationship with this terroir, guided by instinct and sensuality. With the 2018 vintage, I am launching ‘F601, and for the first time, the pure and absolute expression of the fusion between this block of land and the venerable Cinsault vines planted on it in 1928. At this defining moment in my life, I am happy to share with you my sense of wonder in this iconic Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Welcome to F601!”

2020 Domaine Isabel Ferrando ‘F601’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($786)

2020 Domaine Isabel Ferrando ‘F601’, Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($786)

* Details of the 2020 vintage are offered below.

Notebook …

Châteauneuf-du-Pape Vintages

The 2023 Vintage

2023 followed many of the climate-change patterns that have come to dominate in European viticulture. Winter and spring were relatively mild with sporadic rainfall to help replenish dry soils. February, however, saw temperatures drastically plummet as a cold snap took hold. March did not entirely shake off the winter blues, although temperatures rose enough to allow for a successful budburst and May saw the beginning of flowering. Rain continued throughout both May and June and temperatures began to climb. By July, thermometers in the southern Rhône were registering the nineties. The region had to grapple with the threat of drought, and when rain fell, it was violent and occasionally accompanied by crop-destroying hail. Fortunately, September brough cooler nights preserving both aromatics and acidity, and yields ran high. In CdP, Syrah showed well, but Grenache stole the show.

The 2022 Vintage

The year began with a dry winter that produced little precipitation. Spring rapidly warmed up, although April did bring a fleeting cold snap. Temperatures proceeded to rise, although both budburst and flowering were a success. May was abnormally hot but June brought some relieving rain in time for what wound up being an extremely torrid summer. Most of Châteauneuf-du-Pape baked under a Mediterranean sun, but older vines took this in stride while rot and disease were kept at bay. August brought some humidity, which helped revive some of the stressed grapes. Even so, conditions were perhaps more conducive to reds like Syrah and Grenache than whites, although whites with lower acid character like Marsanne, Roussanne and Viognier performed well. Overall, the crop was of very high quality with the promise of sophisticated, age-worthy wines.

The 2021 Vintage

After six blessed harvests in a row, 2021 brought earth back to earth: Temperatures were unpredictable throughout the growing season, without heat spikes, and random thunderstorms later in July served to test vignerons, including a torrential downpour in mid-September right at harvest-time. Early-budders like Syrah, having been jeopardized by spring frost, and the late-ripening grapes also found themselves under threat. Despite this, Mourvèdre, Cinsault, and Carignan fared well, while the quality of Grenache was mixed, some of it (almost unaccountably) particularly good. The best of 2021 wines focus on red rather than black fruit, on lean but elegant tannins rather than any attempts to overcompensate with an ambitious extraction regime or indulgent use of oak.

The 2020 Vintage

Following the extreme heat of 2019, growers were hoping for plenty of rainfall over the winter to replenish aquafers, and they got it. An astonishing 15-20 inches of rain fell between October and December, and a mild early spring saw vine buds break nearly two weeks earlier than in 2019. The summer was hot, but not unreasonably so; rains were moderate and frequent enough to prevent heat stress. Harvest for white grapes began in the third week of August, and the 2020 vintage is extremely strong in this category, however small (only 5% of Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s total). It is characterized by elegance and beauty, with a nose marked by citrus and stone fruit and a palate that combines balanced acidity with a prolonged finish

The 2019 Vintage