Benoît Marguet’s Naturally Grown Champagne Channels His Biodynamic & Homeopathic Practices

True disciples call it wine’s inevitable future, and even the naysayers are beginning to admit that after years of practicing biodynamics, the dividends are irrefutable. And nowhere in Champagne is this more evident than at Champagne Marguet, where Benoît Marguet is one of the few growers in the region to have thrown himself, both body and soul, vineyard and cellar, into homeopathy.

It’s easy to think of Champagne as a spiritual substance; after all, it was created by monks and the very airiness of its identity seems celestial. The cornerstone of biodynamics is a view of the vineyard, and its subsequent produce, in like terms—as a singular organism capable of self-healing and self-propagation. Natural material alone sustains the soil; chemical fertilizers and pesticides are forbidden and instead, a range of animals are encouraged to create a rich, fertile environment in which the vines can thrive.

For Benoît Marguet, this goes beyond biodynamics as a concept; it’s a vision of complete harmony in every stage of winemaking and an improvement in his own personal life which translates into his Champagne.

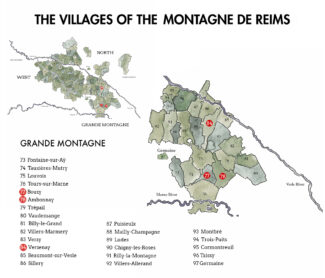

The Montagne de Reims: A Sea Of Pinot Noir

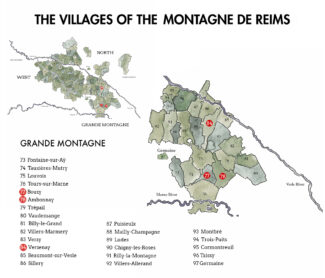

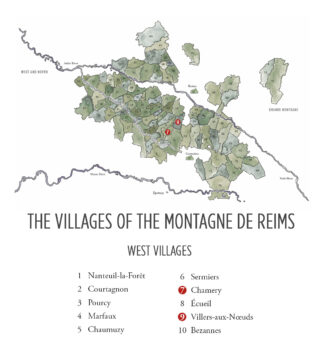

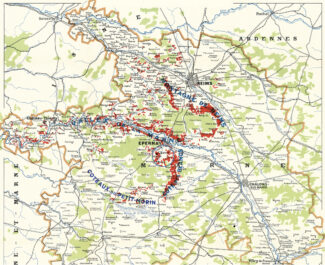

Forming a broad and undulating headland that covers five thousand acres of thicket and vineyard, the Montagne de Reims stretches 30 miles east to west and, north to south, is about five miles wide. The vines hug the limestone slopes of the western and northern flanks and are planted in a huge semicircle that extends from Louvois to Villers-Allerand.

This is Pinot Noir country (except in Trépail and Villers-Marmery, where the Chardonnay can be found). The most northerly of Champagne’s four demarcated regions, the Montagne de Reims is also the most well-known, with more Grand Cru sites than anywhere else in the AOP. Tectonics gave the region mountains of chalk, and the Romans added their two cents by leaving behind huge limestone pits known as crayères. Within, the humidity remains at around 60% and temperatures at a steady 57°F; perfect cellaring conditions to soften the cold-climate acids of Champagne with time on lees. As a result, Louis Roederer, Ruinart, Veuve Clicquot, Krug, Taittinger and Mumm all store wine here.

Champagne Marguet

“A Vitality About The Fruit That Makes It Feel Truly Alive.”

Champagne Marguet has been a bellwether for innovation since 1883, the year that Émile Marguet began to graft his vines onto American rootstocks in the face of the impending invasion of phylloxera. Alas, so ridiculed was the notion throughout Champagne that Marguet wound up tearing out the grafted vines and promptly declared bankruptcy.

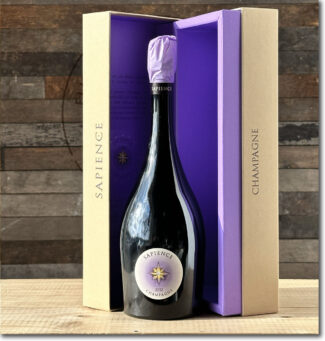

Ratchet forward a century and a half: In 2006, Émile Marguet’s distant scion Benoît Marguet joined forces with Hervé Jestin, the former chef de cave of Duval-Leroy, and began to produce a special homeopathic and biodynamic super-cuvée called ‘Sapience’, first released in 2013. Being on the cutting edge of trends has finally paid dividends.

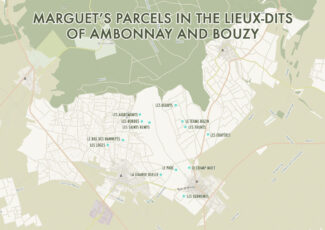

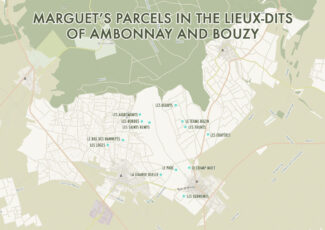

Today, Benoît farms 25 acres of vines, all using biodynamic practices. Most are owned by Marguet himself while the rest are leased from relatives. Among them are eight different lieux-dits with an average vine age of 42 years; each is bottled under the name of the plot and reflects the minute soil differences that exist throughout his holdings as well as the Massale-select varieties he suits to his various terroirs—among them Les Crayères, Les Bermonts, Le Parc and Les Saints Rémys.

The Horses, The Vines and The Eggs

Two techniques keep Benoît Marguet close to his passion; first, since 2009, he has plowed his acres with a pair of draft horses. He argues that by using this method of cultivation roots are forced deeper towards the water table surface, providing a better water supply. In addition, he treats the soil with preparations made of essential oils, tisanes, nettles, citronella, lavender and rhubarb. “The well-being of the soil is a priority,” he points out. “The horse is in connection with the three elements of terroir, the mineral (chalk), the vegetal (vine and flora) and the animal (fauna and human interaction).”

Next, in the cellar, he continues to adhere to the principles of biodynamics by working the wine according to lunar cycles. Under the conviction that the shape of a vat can affect the quality of the wine, he installed special 40-hectoliter egg-shaped wooden cuvée casks produced to his specifications by Tonnellerie Taransaud. The unique shape provides a height/width ratio equal to the Golden Mean or Phi, which Benoît believes is a natural feature repeated throughout the physical world and encourages spiral convection currents and a harmony to better clarify the wine… and his own purpose.

“This symbiosis, with the principle of nature assisting nature, is fascinating research work for me, with influences from various cultures and countries,” Benoît maintains. “In my opinion these fundamental or elemental practices are solutions that instill within our wine its full health benefits, and perhaps even more…”

Blanc de Blancs vs. Blanc de Noirs: Revealing The Fruit

The introductory lesson in Champagne Appreciation 101 is that sparkling wine is made from either light-skinned or dark-skinned grapes, or a combination of both, and all can end up looking a lot the same. This holds especially true in cool-weather climates like Champagne, where vinifying slightly under-ripe grapes is the norm—a point when Pinot Noir and Meunier may not have fully developed their juice-staining anthocyanins. To maintain the desired hue, of course, dark-skinned grapes are pressed gently to keep the skins from bleeding into the juice and the skins separated out quickly.

Holding equally true is the fact that looks can be deceiving. Blanc de Noirs Champagnes made with Pinot Noir and/or Meunier do not share a flavor profile with a Blanc de Blancs made from Chardonnay, and this is the result of both nature and nurture. Generally speaking, a Blanc de Blancs will be a bit lighter and dryer, showcasing the fruits that predominate in Chardonnay’s arsenal—white peach, citrus, green apple and pear. Blanc de Noirs tend to have more body, creamier texture, and the fruit contours are often red; cherry and raspberry, and toasty notes may be more emphatic.

Naturally, the only true lesson in that appreciation course is determining for yourself if you prefer one over the other, and since we are dealing with Champagne, you are more than welcome to respond, “All of the above.”

Champagne Marguet ‘Yuman 2019’ Premier Cru Blanc de Noirs Brut Nature D-2/2022

Champagne Marguet ‘Yuman 2019’ Premier Cru Blanc de Noirs Brut Nature D-2/2022

Yuman is a newer project of Benoit’s that uses organic/biodynamic fruit from two producer friends in Champagne. It is not an estate wine, but is treated just like his other cuvées, seeing a natural fermentation in barrel, and 36 months on the lees. Built upon 100% biodynamic-certified Pinot Noir from the Grand Cru village of Verzenay and Premier Cru village of Cumières, it shows a characteristically crisp acidity behind rich raspberry coulis and aromas of freshly-baked graham cracker.

Champagne Marguet ‘Yuman 2020’, Premier Cru Blanc de Blancs Brut Nature D-3/2023 (Sold Out)

Champagne Marguet ‘Yuman 2020’, Premier Cru Blanc de Blancs Brut Nature D-3/2023 (Sold Out)

A cuvée based on the 2020 vintage; 100% organic Chardonnay sourced from Benoît’s friends Premier Crus Villeneuve-Renneville and Villers-Marmery in the Montagne de Reims. The wine is a wealth of intensity with crisp, chalky, mineral notes and perfumed Meyer lemon on the nose and palate.

Grand Cru Bouzy and Grand Cru Ambonnay: Always Rivals

Like the Hatfields and the McCoys (only without rebel flags and shotguns), Bouzy and Ambonnay have a longstanding rivalry built on begrudging respect and competitive moxie. At its closest point, the distance between the two communes is shorter than a long drive with a golf club, and each have shored up a reputation for superlative wines from the south side of the Montagne de Reims hill.

Yet connoisseurs will happily point out their favorite qualities in each, generally citing the special elegance of wines from Ambonnay, due in part to undulating, south-eastern exposures that moderate the ripening process.

In contrast, Bouzy exposures are almost entirely to the south, ideal for Pinot Noir. More than nine hundred acres in Bouzy are under vine, with 87% of them Pinot Noir, 12% Chardonnay and a scant 0.2% Meunier. The most prominent Champagne houses with a Bouzy presence are Bollinger, Duval-Leroy, Moët & Chandon, Mumm, Pol Roger and Taittinger.

Nearby Ambonnay shares a nearly identical terroir with Bouzy and is similarly appointed, although with slightly less Pinot Noir grown and a bit more Chardonnay—white grapes account for about 20% of the vineyards. Like Bouzy, ‘Ambonnay Rouge’ represents a small portion of wine production. Prominent Champagne houses that control Ambonnay vineyards include Duval Leroy, Moët & Chandon, Mumm, Piper Heidsieck, Pol Roger and Roederer.

2018 Vintage: Pinot Noir Ripened Perfectly. Chardonnay Is Outstanding. Climate Change Is Beginning To Make itself Felt.

2018 checked all the boxes for exceptional Vintage Champagne; the Pinot Noir crop ripened perfectly and the Chardonnay harvest created wines that are full-bodied yet fresh and promise to be long-lasting. Icing on the cake is that the vineyards produced copiously

A few isolated hailstorms led to some crop loss, notably in the Côte des Bar, but the hot, sunny dry days that followed were interrupted only occasionally by (welcomed) rain showers, keeping hydric stress at bay and allowing for optimal ripening at a gradual pace. Harvest was early, beginning on August 20.

Gilles Descôtes, Bollinger’s cellar master, relates his personal experience of the 2018 season: “I experienced this vintage as a relief. As in 2017, we began picking in August, but this time, everything was superb. 2018 is my 26th vintage and I have never seen anything like it.”

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Bouzy Rosé Brut Nature D-2/2023 ($95)

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Bouzy Rosé Brut Nature D-2/2023 ($95)

100% Pinot Noir from the chalky Bouzy terroir. Fermentation (on native yeast) and élevage is done in neutral oak and the wine is barrel-aged with long lees contact and full malolactic. The wine is juicy with ripe red berries and shows a fine bead that permeates a creamy, yet lively texture. 1275 bottles produced.

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Bouzy Brut Nature D-2/2023 ($90)

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Bouzy Brut Nature D-2/2023 ($90)

Fewer than 2175 bottles of this 100% Pinot Noir, zero-dosage Champagne from Benoît’s scant two acres in Bouzy. Having remained on lees for almost four years, the result is an opulent, powerful champagne with apple and yeast aromas and the slightly oxidative style Marguet is known for.

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Ambonnay Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($90)

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Ambonnay Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($90)

63% Pinot Noir and 37% Chardonnay that features a charming, biscuity nose with dried apple and lemon verbena braced by pure, shivery acidity and an underlying minerality.

Champagne Marguet ‘Shaman 2019’, Grand Cru Brut Nature D-1/2023 ($66)

Champagne Marguet ‘Shaman 2019’, Grand Cru Brut Nature D-1/2023 ($66)

Grand Crus Ambonnay and Bouzy. 75% Pinot Noir and 25% Chardonnay. The nose shows candied ginger, dried flowers and orange blossom while the palate is creamy with marzipan, citrus and a salted nut finish.

Champagne Marguet ‘Shaman 2019’, Grand Cru Rosé Brut Nature D-10/2022 ($66)

Champagne Marguet ‘Shaman 2019’, Grand Cru Rosé Brut Nature D-10/2022 ($66)

Grand Crus Ambonnay and Bouzy. 77% Chardonnay, 23% Pinot Noir vinified separately; Marguet works with a Burgundy-like system of Cru selections of single-village wine in good years, and lieux-dits in the best years. Wild strawberries and tea show on the nose, with beautifully integrated tannins and a long, yeasty finish.

Site Specific Grand Cru Ambonnay

Whereas the ‘art’ of Champagne is often discussed in terms of expert blending—much as color is added in layers to create a portrait—a Cellar Master uses a pallet of flavors to create synergy, a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. Traditionally, ‘house styles’ have been established over decades (even centuries) and homogeneity—in the best sense of the word—is the goal. Even vintage Champagne (assembled from a single harvest, though many villages may contribute) should highlight the house approach, since loyal customers expect as much.

So why are site-specific bottlings Champagnes growing popularity? In part because of the rising renown of grower/producers, who are highlighting individual plots of terroir that they themselves have developed. It is trendy (and completely correct) to regard Champagne as wine first and foremost, and as such, individual vineyard expression rather than cookie-cutter (however delicious) house style is simply a new way to view this old standby appellation.

Ambonnay’s vineyards are planted almost exclusively on south-facing slopes on the Montagne de Reims, mostly with Pinot Noir. Together with the vines of neighboring Aÿ and Bouzy, Ambonnay is the source of some of the most powerful Pinot Noir in Champagne; on the now-defunct ‘échelles des crus’, Ambonnay was rated 100%, making it a Grand Cru village.

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Ambonnay ‘Les Bermonts’ Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($120)

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Ambonnay ‘Les Bermonts’ Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($120)

A Blanc de Blancs from Chardonnay vines planted in over an acre in 1952 at the base the slope, unusual for a Grand Cru village noted for its Pinot Noir. The wine features tangerine zest, salt and citrus blossoms behind acacia honey and a vibrant chalk-driven finish. 1848 bottles produced.

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Ambonnay ‘Les Beurys’ Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($120)

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Ambonnay ‘Les Beurys’ Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($120)

The east-facing chalky lieu-dit Les Beurys is slightly less than an acre of 35-year-old vines. The wine displays aromas of apricot, yellow plum and wild strawberry, currants with hints of spice, brioche, and white flower on the nose. Rich with great concentration on the palate, a juicy fruit core with a mineral edge, a fine and delicate mousse with great depth and a long spicy finish. 2141 bottles produced.

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Ambonnay ‘La Grande Ruelle’ Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($120)

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Ambonnay ‘La Grande Ruelle’ Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($120)

Marguet’s Ambonnay vineyard extends over 17 acres in the lieux-dits Les Saints Remys, Les Beurys, Les Crayères, La Grande Ruelle, Les Bermonts and Le Parc; ‘La Grande Ruelle’ 2018 is 100% Pinot Noir from a lieu-dit near Les Bermonts which Marguet believes in one of the best plots in Ambonnay. One acre planted in 1967, the vines thrive in deep clay and limestone soils. The draw took place in June 2019 and the wine was disgorged in March, 2023—only 2160 bottles were produced. The wine displays a great yeasty richness with stone fruit on the nose and a silken, elegant and precise palate.

Grand Cru Verzenay: Chalk About Champagne

It’s a fair bet that the citizens of Verzenay (oddly, called ‘bouquins and bouquines) love their windmill as much as the folks in Beaujolais’ Moulin-a-Vent love theirs. Verzenay’s sits on the Mont-Bœuf hill just west of the village and overlooks a portion of the vineland—1000 acres planted mostly to Pinot Noir. Verzenay Pinots tend to be darker in color than those of nearby Bouzy, where the slopes face south. Verzenay wines are also marked by a characteristic gaminess and an almost metallic undertone. And yet, at the same time, the north facing makes the wine somewhat lighter in weight and more tautly focused.

As usual, Verzenay’s terroir—beyond exposure—is about chalk, or more specifically, ‘super chalk’ built from the remains of microscopic, squid-like belemnites. This chalk sits near the surface in most of Champagne’s hallowed vineyard sites, including Grand Cru Verzenay, and here especially—Pinot Noir country—discredits the notion that such chalky substrate is better suited for Chardonnay.

But why? Above all else, chalk is a highly-efficient sponge, draining away excess water when it rains heavily but, crucially, storing water in times of drought. One cubic meter of pure chalk can store 660 liters of water, so vines in chalk can ride out not only heavy rains, but (increasingly) dangerous droughts which can strip the crop of its elegance and acidity.

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Verzenay Brut Nature D-2/2023 ($90)

2018 Champagne Marguet Grand Cru Verzenay Brut Nature D-2/2023 ($90)

100% Pinot Noir. The nose is expressive with pretty aromas of stone fruit, pear skin, and wet stone; the palate is ripe and concentrated with Rainier cherry and Mirabelle plum. 2072 bottles produced.

The Sapience Project

Aided by a handful of like-minded individuals and completed in Marguet’s winery (with the help of Hervé Jestin), the Sapience Project utilizes the three dominant grapes of Champagne from biodynamic producers—Chardonnay from David Léclepart, Pinot Noir from Benoît Lahaye (and later from Marguet) and Pinot Meunier from Vincent Laval.

The first super-cuvée was in the 2006 vintage, and was named for the patience and experience to reach a full understanding of both the flavors and the concept.

Marguet’s spirit watches over the bottling, which occurs some 9 years from the harvest. It is a labor of love, a wine to ponder, to embrace, and to spend time with, to watch evolve, as the producers involved largely crafted this wine by virtue of decades of dedication to farming.

2014 Champagne Marguet ‘Sapience’ Premier Cru Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($200)

2014 Champagne Marguet ‘Sapience’ Premier Cru Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($200)

Terroirs Grand Cru Bouzy and Premier Crus Cumières and Trépail. Opinions of the 2014 vintage were mixed at the outset (plenty of rain fell throughout the summer) but at disgorgement, the wines have proven sturdy and delightful. 50% Chardonnay, 25% Pinot noir and 25% Meunier, the wine is a study in elegance brightened with freshness, showing creamy lemon curd, spring flowers, hazelnut and a trace of smokiness.

2012 Champagne Marguet ‘Sapience’ Premier Cru Brut Nature D-03-2022 ($200)

2012 Champagne Marguet ‘Sapience’ Premier Cru Brut Nature D-03-2022 ($200)

2012 was an excellent vintage for Champagne was despite the growing season throwing enough curve balls to make most producers nervous. Here, the base wine spends two years aging on forest-selection barrels before the second fermentation. With fewer than 3000 bottles made, it is rare, and has consistently been rated as highly as (or higher than) Salon and Krug.

2010 Champagne Marguet ‘Sapience’ Premier Cru Brut Nature D-01-2020 ($220)

2010 Champagne Marguet ‘Sapience’ Premier Cru Brut Nature D-01-2020 ($220)

A blend of 50% Chardonnay, 25% Meunier and 25% Pinot Noir from vintages 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011 and 2012, the wine is a cooperative effort between four top biodynamic growers, Benoît Marguet, Benoît Lahaye, Vincent Laval and David Leclepart: Leclepart provided the Chardonnay, Lahaye the Pinot Noir and Laval the Meunier, while the vinification was done in Marguet’s cellar. The base wine spends two years aging in barrels before the second fermentation in bottle. With the balance and effortlessness of the best grand marques and the depth of terroir of the best grower Champagnes, the wine provides a creamy nose with hints of dried fruit; warm nut-bread flavors on the palate that are in absolute harmony with the wine’s vibrant minerality.

2010 Champagne Marguet ‘Sapience Oenothèque’ Premier Cru Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($280)

2010 Champagne Marguet ‘Sapience Oenothèque’ Premier Cru Brut Nature D-3/2023 ($280)

Produced only in 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2010, this meticulously crafted wine is a blend of 50% Chardonnay, 25% Meunier and 25% Pinot Noir from prized terroirs in Trépail, Cumières and Bouzy. Disgorged in March 2023 and bottled without dosage, the 2010 Brut Nature Premier Cru offers aromas of fresh pastry, golden apples, white flowers and walnuts followed by a full-bodied, layered and concentrated palate that’s vinous and intense with elegant structure and a sapid finish.

Coteaux Champenois: A Nod To Burgundy

The tale of Champagne’s proximity to Burgundy is told in varieties; Pinot Noir and Chardonnay make up 81% of Coteaux Champenois’ plantings. Also allowed is the other Champagne staple Pinot Meunier along with less cited Arbane, Petit Meslier and the Pinot derivatives, Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris.

Like their fizzy sisters, still wines from the region tend to be dry and light-bodied with naturally high acidity. The reds are better in warmer vintages, which is why the predominant red variety, Pinot Noir, is currently basking in the newfound heat waves of northern France. The reason that 90% of the Coteaux Champenois output is red is not necessarily because the terroir has traditionally favored Pinot Noir, but because locally grown Chardonnay has commanded a higher price when sold to Champagne houses.

But a new generation of grower/producer is taking advantage of the more consistent ripening of red grapes, including Pinot Meunier, to explore terroir and individual lieux-dits in a manner more familiar in Burgundy than Champagne. Says Simon Normand of Domaine La Borderie: “Here in the Côte des Bar we feel quite close to our Burgundian cousins. Many local young winegrowers, such as myself, studied in Burgundy rather than in Champagne.”

Also from the Coteaux Champenois is a unique still rosé called Rosé des Riceys, once a favorite of the Sun King, Louis XIV. Made in tiny quantities by only a small handful of producers, Rosé des Riceys is made through the semi-carbonic maceration of Pinot Noir grapes and can have exceptional aging potential for still rosé.

Domaine Marguet, 2018 Coteaux Champenois ‘Grand Cru Bouzy’ Red ($110)

Domaine Marguet, 2018 Coteaux Champenois ‘Grand Cru Bouzy’ Red ($110)

Produced only in 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2010, this meticulously crafted wine is a blend of 50% Chardonnay, 25% Meunier and 25% Pinot Noir from prized terroirs in Trépail, Cumières and Bouzy. Disgorged in September 2020 and bottled without dosage, the 2010 Brut Nature Premier Cru offers aromas of fresh pastry, golden apples, white flowers and walnuts followed by a full-bodied, layered and concentrated palate that’s vinous and intense with elegant structure and a sapid finish.

Domaine Marguet, 2018 Coteaux Champenois ‘Grand Cru Ambonnay’ Red ($110)

Domaine Marguet, 2018 Coteaux Champenois ‘Grand Cru Ambonnay’ Red ($110)

Pinot Noir requires more hang-time on the vine to fully ripen, and Marguet only produces red Coteaux Champenois in exceptionally warm years; 2018 was one of them. Les Saint Rémys is a parcel of 100% Pinot Noir located on the west side of Ambonnay near the border of Bouzy and produces a lightly-toned red wine with plum, raspberry and sloe on the nose followed by a silky, fruit-driven palate with the tug of stony minerality.

Domaine Marguet, 2018 Coteaux Champenois ‘Grand Cru Ambonnay’ White ($110)

Domaine Marguet, 2018 Coteaux Champenois ‘Grand Cru Ambonnay’ White ($110)

100% biodynamically-farmed Chardonnay from lieux-dits Les Saints Rémys and Le Parc; the nose is floral with aromas of apple white peach blossom, while the palate is concentrated with bees-wax and orange oil flavors with an intense chalkiness at its core. The Grand Cru finish is long and layered.

Notebook ….

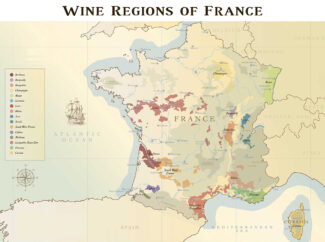

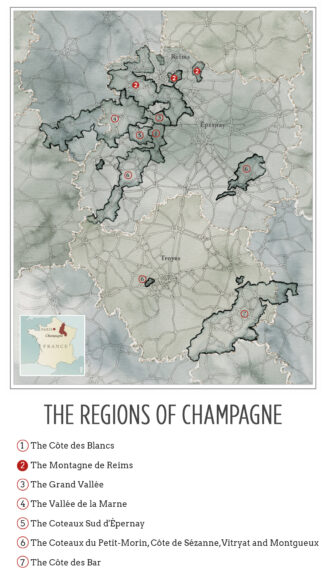

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

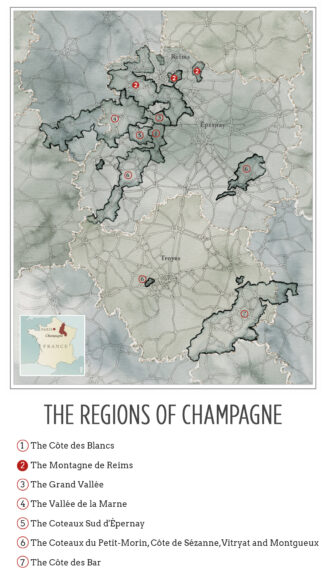

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

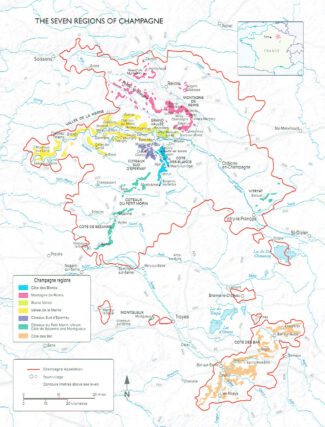

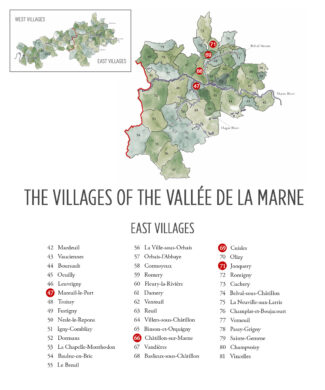

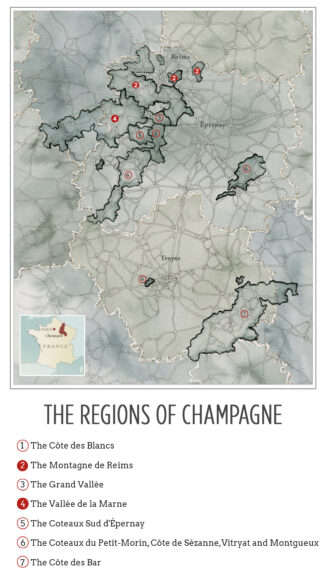

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

The lauded wine writer Peter Liem expands the number of sub-regions from four to seven, dividing the Vallée de la Marne into the Grand Vallée and the Vallée de la Marne; adding the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay and combining the disparate zones between the heart of Champagne and Côte de Bar into a single sub-zone.

Lying beyond even Liem’s overview is a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that compliment or contrast when final cuvées are created.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Épernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

Single Harvest vs. Vintage

In France, under Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) rules, vintage Champagnes must be aged for three years—more than twice the required aging time for NV Champagne. The additional years on the yeast is said to add complexity and texture to the finished wine, and the price commanded by Vintage Champagne may in part be accounted for by the cellar space the wine takes up while aging.

On the other hand, a Champagne maker might prefer to release wine from a single vintage without the aging requirement; the freshness inherent in non-vintage Champagnes is one of its effervescent highlights. In this case, the wine label may announce the year, but the Champagne itself is referred to as ‘Single Harvest’ rather than ‘Vintage’.

A Gift That Keeps On Giving

Membership To ‘The Champagne Society’

Bimonthly Subscription

Not only is Champagne the quintessential drink of celebration, it has traditionally been a gift given with ramped-up sentiments. This year we are offering a couple of variations on this theme, beginning with an opportunity to gift a special someone a six-month or twelve-month membership to The Champagne Society. Our pick for December will be packaged in a wrap-ready gift box along with a congratulatory certificate explaining what lies ahead in bi-monthly installments. For more information please visit our website page: A Holiday Gift: ‘The Champagne Society’ Membership 6-Month ($299) or 12-Month ($589) Subscription.

Not only is Champagne the quintessential drink of celebration, it has traditionally been a gift given with ramped-up sentiments. This year we are offering a couple of variations on this theme, beginning with an opportunity to gift a special someone a six-month or twelve-month membership to The Champagne Society. Our pick for December will be packaged in a wrap-ready gift box along with a congratulatory certificate explaining what lies ahead in bi-monthly installments. For more information please visit our website page: A Holiday Gift: ‘The Champagne Society’ Membership 6-Month ($299) or 12-Month ($589) Subscription.

Elie

- - -

Posted on 2023.12.24 in France, Champagne, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

Back To The Roots Of Wine: A List Of Trios Showcase The Diversity Of France’s Wine Regions A Fresh Look Into What Makes The Country The Wine World’s North Star

The world is a galaxy of wine, and at its center lies a vinous, red-and-white hole of such density that all other wine regions tend to circle it, drawn by the gravity of its reputation and know-how. These other regions are not necessarily ‘pretenders’ and indeed, some of the students have at times transcended the master. They are satellites drawing energy from a mothership called France: Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, all are benchmark varieties in nearly every pocket of the planet that can support them.

Through ups and downs, missteps and natural disasters, the immensity of this tug remains, and at Elie’s, it remains irresistible, even if it may be time to paint over the Mona Lisa.

France has always been its own best friend and worst enemy; a truism in times of war and peace. An epicenter for cuisine and fine wine, it has tended to rest on its laurels a bit too long, until reputation became a stand-in for quality. And then, waking up, in a desperate attempt at reinvention, it has occasionally strayed down rocky roads. Still, the French begin with an advantage denied nearly everyone else—spectacular terroir across the whole of its wine producing regions. Rebounding from the blunders of the late twentieth century, when Robert Parker Jr.’s vaunted love of amplitude over austerity, plushness over earthiness, accessibility over ageability, caused some French vignerons to trade their gracefully-composed French styles for the warm-weather lavishness of Napa’s style, and the changing climate cooperated by stringing together hotter, drier vintages more than capable of producing this sort of wine.

But despite the focus of the mainstream press, the soul of French wine has always been found in the beautiful countryside, and as a younger generation of winemakers comes of age, and embraces new/old concepts like biodynamics and revitalized vineyard soil, there is New French wine movement taking hold. The depredations of industrial farming is beginning to be seen in a rear-view mirror and once again, the concept of ‘terroir’ is not viewed as a marketing tool; it is seen as an indispensable passport to identity.

As die-hard fans and unabashed Francophiles, Elie’s is pleased to be at the forefront of discovery, especially when new faces appear at old venues. Some are scions, others pioneers, but the fact remains that now, and for the foreseeable future, French wines not only matter, but when they live up to their best ideals, remain the lodestar for the global wine industry.

The New Frence: Neoclassicism and ‘New Wave’ Wines. (The Myth of An Immutable France.)

Terroir may be written in stone (and soil and climate) but culture is not. Although wine represents the most valuable sector of French agriculture, the attitude of the people toward it has changed rather dramatically over the past few decades. Wine consumption in France is half what it was in the 1960s; younger generation that has turned away from wine more than any other age group. In February 2023, Agriculture Minister Marc Fesneau announced plans to help the industry respond to what he described as a ‘crisis in the wine sector’, including financial aid for producers wishing to distill excess wine and supporting growers by developing longer-term plans in light of climate change challenges and evolving consumption patterns.

In the meantime, the ever-resilient old guard, refreshed with novel ideas as a new generation takes the reins, has laid the ground work for what author Jon Bonné refers to as ‘neoclassicism’—a return to the roots, where wines taste more transparently of its origin, and regions not previously regarded for quality have discovered that a host of new techniques—bolstered by warmer, drier weather—has transformed outlying appellations from blips on the radar to regions that demand our attention. And in a land where time-honored tradition is sacred, this shift in thinking is nothing short of seismic.

At Elie’s we have followed these trends with our own personal microscope, wandering the hectares, talking to the vignerons, sampling from cellars full of this new-wave of French wines. As France is not immutable, neither are we, and armed with both a love for French wine and a fascination with its expansive evolution, we will do our best to be the most comprehensive source of neoclassical French wines on this side of the Atlantic.

Climate Change Pushes Vignerons To Rethink Winemaking Practices

Freak frosts and soaring temperatures, devastating droughts and downpours, sultry winters that encourage vines to bloom before their time—these are mere symptoms of the larger condition (which may, in many cases, be called a catastrophe) known as global warming. In France, where many vineyards exist in a precarious ‘Goldilocks zone’ of grape viability, this phenomenon has forced changes in such practices as have seen winemakers through centuries.

Short of lighting up hundreds of flaming candles and using the downdraft from helicopters to protect precious young buds (as occurred across France in 2019), winemakers are clenching their hidebound teeth and replanting vineyards to previously ungrowable varieties. The Jura, for example, is producing higher-quality Pinot Noir than ever before and vintners are delving back in time to the historic varieties of the area that were abandoned decades ago. Producers are rethinking canopy management, vine trellising and pruning techniques, developing cover crops and extensive shading methods, increasing vineyard biodiversity and finding ways to reuse water during droughts.

Climate change is complicated, and even if temperature is the most influential factor in overall growth and productivity of wine grapes, there’s far more to consider: Rainfall is pivotal, and too much rain during harvest season can lead to watery grapes and a weak vintage, while humid conditions in the spring lays a welcome mat for pests, fungi and mildew. Rising sea levels play a role as well, and it is likely to get worse: According to NASA, oceans worldwide are estimated to surge at least 26 inches by 2100, and will decimate coastlines and their sway over nearby viticultural regions.

Alsace

According to many of us, the wines of Alsace are criminally under-represented on most wine lists and in most collections, but in this cool corner of northeast France is surfacing those eager to carry forward the torch. To each of them, a critical question arises: “Do I continue to make wines in the style my fathers and grandfather, or implement changes to show a different approach?”

Jean-Frédéric Hugel from Hugel in Riquewihr responds this way: “If you need proof of climate change, ask vintners; grapes and are great witnesses of it. At the beginning of his career my grandfather saw a regular harvest start on October 15th, so that’s when he brought in bring pickers to start a six-week harvest. Today we harvest in 4 to 5 weeks and start on average 15th of September and in 2018 and 2017, the 7th and 5th of September, with sugar content far higher than in later harvests of the past.”

Overall in Alsace, climate change has been a blessing, as in the past, the main challenge was ripening grapes. On average, the region once saw two unripe vintages per decade and produced wines that would have been unsellable in the current market. Now, they are rare, while the two ‘exceptional’ vintages per decade that Alsace once enjoyed has become four, and often, six.

$89 White Alsace Trio: Riesling, Gewürztraminer, Pinot Blanc

Alsace Riesling, Domaine Weinbach ‘Cuvée Théo’ 2019 white ($39)

An elegant, pure and aromatic Riesling from the Weinbach clos, made with biodynamic grapes; it offers ripe citrus on the nose, yellow peach on the palate and a salty-piquant finish with plenty of athletic acidity.

Alsace Gewürztraminer, Domaine Mann ‘L’Oiseau Astral’ 2020 white ($30)

‘The Astral Bird’ is an expressive Gewürz from Biodyvin-certified vineyards; it shows nice extracted fruit, with lychee and mangosteen in the forefront and spicy acidity that gives it remarkable length.

Alsace Pinot Blanc, Domaine Schoffit ‘Vieilles Vignes’ 2020 white ($20)

A blend of Pinot Blanc and Pinot Auxerrois, from a plot where the average vine age is fifty years. Expressive up front with musky floral tones and a succulent apple core, a wisp of sweetness, zesty acids and plenty of grip on the finish.

Burgundy

As writer Jon Bonné maintains, “It’s not that the world hasn’t always revered Burgundy, but the past two decades have been very good to this sliver of eastern France. The Côte d’Or has become the darling of wine lovers as no other place has—its popularity today is unprecedented and its best vineyards and producers are the stuff of modern legend. Fans pore over esoteric maps and data in a way that verges on fetish, and they pay dearly to celebrate with their fellow Burgundy lovers.”

Even so, at the turn of the twenty-first century, Burgundy was just beginning to recover from disastrous winemaking decisions that marked the late 1980s and early 1990s, when red Burgundies were often deeply extracted and thick and aged in too much new oak with the goal of emulating the bigger style of Pinot Noir gaining favor at the time. The whites, in contrast, had a tendency to oxidize prematurely.

These days, the requisite changes in thinking are being wrought by pioneering, educated and confident winemakers, many of whom are very young. Organics and biodynamics are understood as being the only logical choice to restore terroir (rather than marketing) as the essence of the Burgundian persona.

$142 Red & White Burgundy Trio: Givry, Mercurey, Rully

Givry, Domaine de la Ferté Premier Cru Clos de la Servoisine 2020 red ($44)

The Clos represents just under two acres of vines planted in the early 1970s in dense clay and silty soils. Natural yeast fermentation followed by aging in large foudres; the wine shows lush blackberry with an edge of dark chocolate and spice, supple tannins and a balanced finish.

Mercurey, Gouffier Premier Cru Clos l’Évêque 2020 red ($49)

Hand-harvested organically-grown grapes vinified 40% whole cluster and aged in 228 liter barrels for a year. It offers silken cherry notes, earthy forest floor, bramble berries and a lean, chalky finish.

Rully, Domaine Michel Briday Premier Cru La Pucelle 2020 white ($49)

From an acre and a quarter planted on shallow clay; this Chardonnay comes from 45-year-old vines and shows richly concentrated citrus notes, green apple, white flowers and a touch of toast and flint on the finish.

Beaujolais

‘Beaujolais Nouveau’ may stir up some unpleasant memories, but New Beaujolais—coming of age during the global climate crisis—is different sort of critter. The pitfalls are legion: “It’s easier to find a drought-resistant grape variety than it is to convince both producers and wine-loving public to drink it,” says Natasha Hughes, MW. For Beaujolais, a one-trick pony named Gamay, the experimental mix of Alsace and Rhône varieties may be a hard sell, but it forms a component of research by Sicarex—an organization working on behalf of Beaujolais to mitigate the worst excesses of climate change.

Even so, that is not how the story of modern Beaujolais will likely resolve itself. Gamay will not only survive intact, it may well become a younger generation’s substitute for the red Burgundy they cannot afford and are likewise unwilling to invest the time required for it to reach full maturity. Wines built for upfront drinkability, made without status markers like new oak, are becoming not only acceptable, but embraced as great wines. Beginning in the 1980s, a group of Beaujolais winemakers began to reconsider farming practices and cellar work, believing that ripe fruit and diligent, controlled winemaking with native yeasts could make far better Beaujolais. Their legacy is obvious today, and Beaujolais—the Crus especially, but not exclusively—are a totem of how wine itself has changed.

$125 Red Beaujolais Trio: Morgon, Fleurie, Moulin-à-Vent

Morgon, Mélanie et Daniel Bouland ‘Pré Jourdan’ 2021 red ($39)

Ample and fleshy, the wine displays a rich nose of raspberries, cherries and sweet spices, with espresso, wood smoke and ripe tannins in the mid-palate.

Fleurie, Domaine Chignard ‘Les Morier’ 2021 red ($29)

‘Les Morier’ is an exceptional vineyard, steep and stony with a granite core, and a portion of it reaches into Moulin-à-Vent—an appellation known for its structural depth and Rhône-like aromatics. True to form, the wine is velvety and fleshy, showing mulberry and cherry preserves over a focused, elegant nucleus.

Moulin-à-Vent, Château du Moulin-à-Vent ‘’Les Vérillats’ 2019 red ($57)

At 1000 feet, Les Vérillats perches atop the hill, even above the famous windmill, where a thin layer of sand covers pink granite. 45-year-old vines give the wine enviable depth and structure to support notes of mature red and black fruit, hints of spice and a persistent floral river of rose, peony and violet.

The Loire

The Loire, from Muscadet to Sancerre, is another French wine region that is changing so rapidly that it is difficult to keep up. The natural wine movement finds its unofficial headquarters here, and if the gorgeous châteaux and picturesque chalky-limestone villages speak to the past, the winemakers have their sights set on the future. Whereas the Loire’s white wines have long held a reputation for their remarkable depth, particularly among white Burgundy lovers seeking an affordable substitute, and the reds, generally made from Cabernet Franc, have legions of Bordeaux fans, they are increasingly seen as something more than an alternative wine. They have established a modern reputation of being soulfully complex and savory, remarkably expressive of their individual terroirs.

“In the 1980s, the wines were known for being easy and simple,” says Matthieu Vallée of Château Yvonne, one of Loire’s up-and-coming talents. “Now it’s finally changed, and people can see a different side.”

$97 White Loire Trio: Muscadet Sèvre-et-Maine, Sancerre, Montlouis-sur-Loire

Muscadet Sèvre-et-Maine, Complemen’ Terre ‘La Croix Moriceau’ 2021 Natural white ($29)

The Melon de Bourgogne grapes are manually harvested and stainless steel tanks are used for débourbage before racking into smaller concrete vats for fermentation and elevage for 7-8 months. The wine then undergoes malolactic fermentation, and minimal sulfur is added at bottling. The wine is racy and tight, with macerated apple notes and a slight, pleasant oxidation and on the finish to accompany crushed stone, salinity and a whiff of campfire.

Sancerre, Domaine Claude Riffault ‘Les Boucauds’ 2022 white ($36)

The Sauvignon Blanc grapes are grown in the deep clay of Les Boucauds lieu-dit, which lends fullness to the fruit and produces a tropical profile with melon, pear and pineapple alongside white flowers.

Montlouis-sur-Loire Sec, Le Rocher des Violettes “Le Grand Clos” 2020 white ($32)

The Chenin Blanc grapes originate in three lieux-dits in Mont-Louis, Les Borderies, Le Grand Clos and Bel Air. These are the oldest vines of the estate (90+ years old) and are subjected to high density plantings on south facing slopes where the terroir is clay and silex above pure chalk. The wine shivers with crystalline acidity and shows flecks of richness amid white flowers, ripe lemons and subtle honeyed notes.

Bordeaux

Dollar for dollar, Bordeaux produces more wine than anywhere else in France; its marketing power, reputation and history have impelled it to a pinnacle in the imagination of most of us. Still, the perch is precarious, in part because it has largely been built around the 1855 classification system that ranks its top properties. And nearly everyone not atop that pyramid views it as past its expiration date.

Of Bordeaux’s 8,500 properties, only about 120 benefit from this hierarchy, and if ever a wine region was screaming for an updated perspective, it’s Bordeaux.

Even the hidebound Conseil Interprofessionnel du Vin de Bordeaux (the Bordeaux Wine Council, formed in 1948) seems on board. Six new grapes join Bordeaux’s previously approved varieties in an effort to adapt to climate change, and the area home to a growing number of producers making eminently drinkable wine at artisan scale, while avoiding the style wars that have fueled the region’s woes.

As can be seen elsewhere in France, biodynamics and biodiversity, and often, lighter extractions closer to the classic ‘claret’ style, is a stand against the hive mind in Bordeaux. This is being driven by vignerons rather than public relations firms, people who believe in human-scale Bordeaux and who farm with an eye toward organics and who revere the freshness and integrity that has made the region so beloved.

$124 Red Bordeaux Trio: Saint-Estèphe, Saint-Émilion, Pessac-Léognan

Saint-Estèphe, Château Capbern 2020 red ($38)

A Cabernet Sauvignon-dominated blend that includes 37% Merlot and 1% Petit Verdot, all of which was brought up in 60% new barrels, resulting in a deep, dark, earthy, classic Saint-Estèphe with cassis and blueberry as well as ample chocolate, damp earth and leafy herb-like aromas and flavors.

Saint-Émilion, Château Laroque Grand Cru Classé 2018 red ($44)

97% Merlot and 3% Cabernet Franc from one of the highest sites in the appellation. The wine shows flamboyant notes of stewed plums, Black Forest cake and boysenberries plus hints of candied violets, star anise and tobacco leaf with a waft of sassafras.

Pessac-Léognan, Château le Thil Comte Clary 2020 red ($42)

Blackberries, currants and hints of hazelnut form the framework of a sensuous and lithe wine with multiple spice nuances—cloves, ginger and soft mint.

The South-West

Nowhere in France is the notion that ancient grapes do best in their native soils more pronounced than in the southwest; critics and rule makers be damned. Some of these grapes grew wild, while others found places where they thrived after Roman soldiers and medieval troubadours carried them through hills and valleys. Though the cast is enormous, many of these vines are not found elsewhere and are varieties with which many of us are only peripherally familiar: grainy Négrette, small-berried Petit Manseng, local Tannat whose name, it is assumed, derives from its mouth-puckering tannin content. Some are grapes that have all but disappeared, but are now being revived by growers who revel in the homegrown DNA and are modernizing tradition rather than breaking with it.

Having at one time receded into the role of humble country wine, a new generation of vignerons in the southwest are beginning to produce remarkable, avant-garde wines. Natural-minded, new-wave winemakers are appearing on the scene with increasing regularity. They seem to have a deep appreciation for the nuance and depth of southern traditions, maintaining its bounty of local grapes and eager to connect best of the countryside’s past to the future. They are quiet heroes and quality-focused pioneers demanding change from the twentieth-century norm and the Southwest’s blandly commercial path.

$101 Red & White South-West Trio: Cahors, Côtes-de-Bergerac, Bergerac

Cahors, Château du Cèdre “Extra Libre” Natural 2019 red ($31)

The winery eliminated the use of chemicals in 1992, emphasizing sustainable practices and minimal intervention in the vineyards—this blend is 90% Malbec, 5% Merlot and 5% Tannat, hand-harvested from vines between 15 and 30 years of age, fermented in concrete tanks, then aged 12 months in large, used barrels. The wine shows vibrant acidity, to brace its dark fruit, cocoa and very fine tannins.

Côtes-de-Bergerac, Château Tours des Gendres ‘La Gloire de Mon Père’ 2018 red ($31)

A blend of 53% Merlot, 35% Cabernet Sauvignon and 12% Cabernet Franc that spends 12 months in oak and six months in bottle before release. A smooth and creamy palate juicy with concentrated blackberry and cherry notes, a hint of smoke and a long, mineral-driven finish.

VdF Bergerac, Combrillac ‘Petchalba’ 2021 white ($39)

An interesting and unusual blend: 50% Sauvignon Blanc, 40% Sémillon and 10% direct-pressed Cabernet Sauvignon. Named for a Macedonian rite of passage, the wine is aged in a mix of Italian sandstone amphorae and used barrels and bottled without fining or filtering.

Jura

‘Voile’ is a term that most wine people associate with the Jura’s late-harvested Vin Jaune—a thin veil of yeast that floats atop the vat to toughen and mature the must, exposing it to limited amounts of oxygen. But in the Jura, it is used not only in their famed, sherry-like ‘yellow wine’, but in many others based on the local Savagnin variety.

It’s an interesting method, not to everyone’s tastes, and perhaps a problem as modern wine drinkers look more and more to terroir and less to technique. But the switch is not far-fetched in Jura, whose soil is somewhat similar to its grand neighbor to the west, Burgundy (both sit on an ancient seabed) and limestone and clay in varying configurations that can accommodate Chardonnay as well as Savagnin. Ironically, in Jura, the radical reinvention is to go more mainstream—Jura’s conventional winemaking is unconventional in the rest of France, and a growing number of winemakers believe that it blurs the region’s true potential.

“With the traditional style, all the wine was looking similar after oxidation with the veil,” says Julien Labet, one of the champions of the new style, called ‘ouillé.’ “They all had that nutty taste, and didn’t have the personality they had before the veil.”

Resistance has been marked, largely because the Jura enjoys its reputation as an outsider and frowns on any changes designed to erase its uniqueness. Still, there is little chance that the appellation will ever become ‘like everybody else.’ Chardonnay planted to densely spaced, head-trained on the Jura’s terroir yields wine that are more savory and saline than their Burgundian cousins, their fruit and flavors a bit more generous.

Crémant-du-Jura Brut, Domaine Overnoy-Crinquand ($33)

100% Chardonnay with 30 months of lees contact and a mere 0.5 grams per liter dosage. A non-vintage wine but produced exclusively from a single vintage, it offers textural plushness and breadth balanced by iron-tinged minerality and a gently honeyed character.

L’Étoile, Domaine de Montbourgeau 2017 white ($30)

95% Chardonnay with Savagnin topping off the blend, this wine originates on the southeastern slopes of L’Étoile, where vines average 40 years. Following malolactic fermentation, it spends up to three years in neutral oak, giving it what may be considered a ‘typical’ Jura profile for Chardonnay, tasting slightly oxidized, although not nearly in the style referred to locally as ‘sous voile’, or ‘under veil’—referring to the yeasty flor that characterizes Vin Jaune. About 20,000 bottles are produced: It is the winery’s mainstay.

L’Étoile, Domaine de Montbourgeau 2011 ‘Vin Jaune’ ($89)

Befitting the style, this Vin Jaune is 100% Savagnin grown on blue marl rich in limestone. The wine spends one year in small, neutral oak casks followed by six years in larger hogsheads, allowing for the longer, requisite maturation period. The wine displays quince jam notes sheathed in warm, yeasty lemon curd and resonant acidity. Around 3000 bottles made.

Savoie

Metaphors linking wine to its place of origin are the stuff of poetry, but they’re also the foundation of terroir. Among the most common descriptors of the area’s high-altitude wine is ‘refreshing’ which is an offhand way of saying that it tends to be lower in alcohol and higher in acidity than valley wines. These acids are often the end result of the cool mountain air which they resemble, giving distinct, cleansing mineral characteristics to the wine with citrus and herbs rather than jammy fruit. Alpine wines have a crunchy sizzle and a cool sappiness unlike wine from anywhere else. Not only that, but the predominant grapes don’t show up on many other radars, so the unique textures commingle with a whole new flavor profile to surprise and delight the palate.

Over the past twenty years, a new wave of independent vignerons has been boosted by organizations dedicated to preserving these singular grape varieties, and Savoie has finally begun to come into its own. Natural wine is increasingly becoming the order of the day—elevations are such that the mildew that affects vines at sea level is not an issue, and like wines from the Jura were a decade ago, Savoie wines are still considered somewhat geeky and under-the-radar—which makes it an ideal region for innovative winemakers from a younger generation to make their mark.

$114 Red & White Savoie Trio: Savoie, Savoie-Arbin, Roussette-de-Savoie

Vin de Savoie, Domaine Marie & Florian Curtet ‘Frisson des Cimes’ Natural 2019 red ($45)

An interesting blend of organically-farmed Mondeuse, Gamay and Pinot Noir planted in sandstone with a southwestern exposure. It is made with whole cluster fermentation and without pump overs, which lasts around a month before pressing. This is a dark, pungently earthy wine with notes of mulched forest floor, black plum, blueberries, pine, Kalamata olives and roasted meat.

Vin de Savoie Arbin, Blard & Fils ‘Mondeuse Noire’ 2020 red ($39)

Mondeuse is a local variety often described as a cross between Pinot Noir and Gamay with a touch more tannin. This offering is grown in clay and limestone soils and there is a pronounced iron-rich mineral note on the nose along with red fruit and lacy mouthfeel.

Roussette de Savoie, Blard & Fils ‘Altesse’ 2020 white ($30)

Made from 100% Altesse grown on Mont Granier scree—a mix of clay and limestone with a bit of marl and silex. 80% of the grapes are direct-pressed while 20% are destemmed and macerated on the skins for 10 days. The wine is wild yeast fermented and aged on the skins in stainless steel tanks for 10 months and bottled without filtering or fining. A nice backbone of acidity sets off notes of bergamot, honey and hazelnut, mountain herbs. As an aside, the traditional pairing for Roussette de Savoie is Raclette and its typical sides of boiled small potatoes, charcuterie, and apricot mustard.

The Rhône: North

Fifty years ago, both Côte-Rôtie and Cornas along with much of the northern Rhône, were struggling just to survive. Around 1966, when the appellation had fallen into obscurity, its overseers simultaneously decided to revive quality, but also to expand to the flatlands above its rocky granite and schist terraces. The appellation’s traditional method of farming steeply-sloping vines by hand made for pretty images, but were a curse financially. The expansion ended a traditional style of Côte-Rôtie that had been fresher, even a bit light, and more overtly spicy than fruity.

By the 1990s, the most popular wines of Northern Rhône were thick and heady, made with carefully controlled fermentations, heavy extractions and plenty of new oak. As the climate warms, the conditions that produce big, high-alcohol wines are becoming the rule of the day. Not only that, but rising temperatures parallel the rising cost of vineyard acres, and many properties are being snapped up by wealthy overseas investors who care more for market appeal than subtle winemaking.

But a number of smaller, previously dormant areas that nestle in pockets near the big-name appellations in the Rhône have begun a remarkable comeback; this is the result of hard work by few steadfast vignerons who have saved noteworthy properties from being reclaimed by forest. It is among these parcels of land, which peek through mostly unfriendly hinterland that we make our modern-day discoveries— worthy and exciting Syrahs; the best made since the phylloxera blight wiped out the original vineyards in the 1800s.

$124 Red Northern Rhône Trio: Côte-Rôtie, Crozes-Hermitage, Saint-Joseph

Côte-Rôtie, François & Fils 2019 red ($67)

Classic Côte-Rôtie notes of violets and crushed blueberries bathed in silky ripe tannins. A traditional co-ferment with 4% Viognier that offers a floral lift and a touch of nutmeg in the finish.

Crozes-Hermitage, Domaine Jean-Claude et Nicolas Fayolle ‘La Cuvée Nicolas’ 2020 red ($25)

100% Syrah from youngish vines grown in Gervans, a small granitic outpost within CrozesHermitage. Full-bodied without being heavy, ripe without being jammy, the wine is juicy with brambly wild berries, licorice and creamy mocha tones.

Saint-Joseph, Domaine Éric et Joël Durand ‘Les Coteaux’ 2017 red ($32)

Big-shouldered, yet velvety, concentrated and rich, the wine shows cherry and plum pudding infused with anise and accented by warm fruitcake spices.

The Rhône: South

2021 is an example of the sort of challenging vintage the producers in Southern Rhône are facing; a wet winter was followed by an unseasonably hot spring, followed by an extensive frost in April that drastically reduced yields. In November these climatic extremes reduced overall French wine production by 27 % and the vintage proved to be one of French wine’s most difficult years on record.

But the effects of climate change are hardly restricted to a single season. In recent years, each individual vintage has presented its own unique set of trials, an inevitable offshoot of rising temperatures, which on average have increased 1.5°C; predictions are that things will get worse. Of course, it’s not limited to France, but the delicacy of the vineyard ecosystem is Southern France is being battered by heat waves, drought and fires, there are also spring frosts, hail, and excessive rain with damage wrought by one or more in any given year.

As the world is eager for Rhône wine and winemakers understand they must be willing to provide enough of it, they look for a silver lining, even if it means rethinking France’s longtime wine regulations. As relatively new appellations like the villages of Gigondas and Vacqueyras gaining fame, attention has turned to other, as-yet-unexploited areas where climate change may be a blessing in disguise. Historically, elevation has not been a defining characteristic of the region, as the vast expanses of the Côtes du Rhône to Cru appellations like Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Gigondas and Vacqueyras, the vineland is characterized by rocky flatlands where ample sunlight pumps richness into the wines.

According to Christian Voeux, owner and winemaker of Domaine de l’Amauve, located just north of Gigondas, “In the past, altitude was not considered an advantage for winegrowers in Southern Rhône. High altitudes would delay the maturity of grapes, and when full maturity was finally reached at the end of September or October, heavy rains would come, affecting the quality of grapes.”

Over the last two decades, climate change has rewritten the rule book. Throughout the Southern Rhône, a steady annual increase in temperature has expanded the possibilities for viticulture into a diversity of hillside terroirs rimming the valley, while those on the ground level may suffer the fate of most grapes pushed extreme ripeness in shorter ripening cycles, yielding blowsier wines with lower acidity levels.

$137 Red Southern Rhône Trio: Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Gigondas, Lirac

Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Clos Saint Jean ‘Vieilles Vignes’ 2019 red ($58)

A blend of old vine Grenache, Syrah, Mourvèdre, Cinsault, Vaccarèse and Muscardin located in and around lieu-dit Le Crau. The Grenache is aged in concrete for 12 months while the remainder is aged in demi-muid. The fruit is reminiscent of warmed plum sauce and blackberry purée, while the savory side shows up as garrigue, earth and toasted spice.

Gigondas, Domaine Santa Duc ‘Clos Derrière Vieille’ 2018 red ($57)

Produced from old vines in limestone-rich soil, the blend is predominantly Grenache shored up with Syrah and Mourvèdre. Classic Gigondas terroir appears as ripe blueberry and strawberry mingled with black pepper, fresh green herbs, earth, resin and anise.

Lirac, Domaine du Clos de Sixte Lirac 2019 red ($22)

50% Grenache, 35% Syrah and 15% Mourvèdre grown organically under Ecocert. The vineyard soil is mostly limestone, alluvial soils with quartz, sand and rock. Fermentation takes place in stainless steel with hand-sorted, crushed and destemmed grapes.18 days of vatting with pigéage is followed by 16 months in concrete vats and 30% new French oak barrels. The bouquet shows blackcurrant liqueur and pie spice, the palate is full, harmonious and elegant with licorice and vanilla on the finish.

Provence

Once known primarily for somewhat generic pink wine, Provence is—like the rest of France—in the middle of self-examination. It’s true that they are ‘redefining’ game somewhat later than most appellation, primarily because in the words of winemaker Henri Milan (Domaine Milan). “We live in a parallel universe here, entranced by our own charmed lives and abandoning any thought of the world beyond.”

Those lives, beyond the famous rosés, also include Bandol’s Mourvèdre, Cassis’ Clairette, and various permutation of the ancient grape Tibouren. But a handful of pioneers, exploring the back country and delving deeply into the soil, have begun to work with old vine Grenache and Cinsault while discovering that little-known and colder subsets of Provence have warmed to a level where the full diversity of southern grapes can be planted successfully and produce wine without the characteristic heat and high alcohol and retain the essential freshness that discerning palates appreciate.

$137 Red & Rosé Provence Trio: Bandol, Les Baux-de-Provence, Côtes-de-Provence

Bandol, Domaine Roche Redonne ‘Cuvée Les Bartavelles’ 2019 red ($69)

95% Mourvèdre and 5% Grenache; the wine’s cuvée name honors the local rock partridges. The vines average 40 years old; the youngest are 20 years and the oldest, 60. The yields are very low and the steep-hilled vineyards can only be harvested by hand. The wine shows boysenberry, blackcurrant, pepper and graphite shored up with well-integrated tannin.

Les Baux de Provence, Domaine Hauvette ‘Cornaline’ 2012 red ($41)

Cuvée Cornaline is a plush blend of 50% Grenache, 30% Syrah and 20% Cabernet Sauvignon farmed biodynamically on cretaceous limestone terroir. Grenache brings fresh strawberry and thyme to the profile, Syrah, black pepper and olive while Cabernet Sauvignon gives its black currant, tobacco and a light, enjoyable smokiness.

Côtes-de-Provence, Domaine Gavoty ‘Grand Classique’ 2022 rosé ($27)

Made of Grenache and Cinsault in roughly equal proportions. Rather than being pressed immediately after harvest as many Provence rosés are, Grand Classique macerates for several hours before pressing, and the saignée and first-press juice are vinified separately. The resulting wine shows strawberry and watermelon electrified by racy acidity.

The Languedoc

The Mediterranean Sea takes a sizeable chunk out of France’s hindquarters, and the bite-shaped crescent contains a few of the most dynamic winegrowing regions in the country. Clockwise, from just north of Spain, Languedoc is a swarthy appellation known for Grenache and Carignan blends—two varieties that love the hot coastal sunshine. Often joined at the hip with neighboring Roussillon, the insanely productive AOP accounts for more than a third of the country’s wine output. Historically, this wine was copious, inexpensive and rather forgettable—everyday wine for the tables of ordinary people. Since the mid-twentieth century, however, with the advent of irrigation in the foothills and coastal plains of Southern France coupled with improved techniques, the region now boasts fewer vines that produce wines of increasing quality.

A jigsaw of soils and a broad swath of microclimates creates ideal terroir for the warm-weather, full-bodied varietals often associated with the Rhône, while sharp diurnal shifts allow for the preservation of aroma and natural acidity, resulting in wines of extraordinary balance. A further plus is that Languedoc-Roussillon’s hot, dry climate discourages the growth of mildew and fungi, making synthetic pesticides and herbicides less necessary. As such, it has become a proving ground for organic and biodynamic producers.

$119 Red Languedoc Trio: Faugères, Terrasses-du-Larzac, Languedoc-Hérault

Faugères, Domaine Léon Barral ‘Jadis’ 2016 red ($47)

‘Jadis’ roughly translates as ‘long ago’ or ‘in olden days’—a wistful glance at the traditional way of doing things. Old vine Carignan and Syrah from the domain’s southern-facing vineyards, the wine offers exotic layers of musk, sour cherries and herbs with a mineral and saline finish.

Terrasses-du-Larzac, Mas Cal Demoura ‘Terre de Jonquières’ 2017 red ($32)

30% Syrah, 25% Carignan, 20% Cinsault, 15% Mourvèdre and 10% Grenache, with each variety vinified separately. The initial fermentation occurs in temperature-controlled stainless steel vats, after which the wines are racked into barrels and, after one year of aging, blended. The wine is given an extra six months of aging before being bottled without fining or filtration. The wine offers black fruit, licorice, and garrigue and remains elegant and fresh on the palate.

VdF Languedoc-Hérault, Clos de la Barthassade ‘K Libre – Carignan’ 2019 red ($40)

50% whole cluster Carignan and 24 months élevage in demi-muid and concrete egg produces a wine with an amazing array of spices on the nose; potpourri, Asian spices and sandalwood with a bright mineral overtone and a touch of smokiness. The palate is driven by fruit, especially raspberry.

The Roussillon

Author Jon Bonné refers to the sweet, fortified, Grenache-based wines of Banyuls as ‘Port that isn’t trying too hard.’ Likewise the Muscat-based wines of Rivesaltes, just to the north, whose fully oxidized, dry wines native come across like France’s response to Sherry.

But the real interest in today’s world is dry, intensely mineral red and white wines being made there these days; a factor that may be confused when Roussillon’s best dry wines are lumped in with Languedoc to the north, doing a disservice to both appellations. Roussillon’s current focus is clear: Acid-driven wines that are unquestionably southern, but also subtle, as winemakers have found a way to modulate the sun. In part this involves impeccable, often organic farming to make wines whose complexity rivals top Rhônes.

Roussillon’s affordable land also makes it a magnet for a lot of natural-wine pioneers including naturalist icons like Edouard Laffitte of Le Bout du Monde, whose easygoing wines mirror those of several like-minded vignerons and prompted their village of Lansac to be dubbed Jajakistan—an in-joke derived from French slang for gluggable wine.

$104 Red Roussillon Trio: Collioure, Maury, Corbières

Collioure, Coume del Mas ‘Quadratur’ 2016 red ($37)

50% Grenache Noir, 30% Mourvèdre and 20% Carignan from high-altitude old vines with concentrated, low yield fruit. In the winery, strict hand and table sorting precedes a long maceration and fermentation intended to extract maximum flavor, followed by 12-14 months in oak barrels before bottling without filtration. The wine showcases delicious notes of dark fruits, spices, wild herbs and earth.

Maury, Mas Amiel ‘Alt.433m’ 2017 red ($36)

The plot for this wine was planted in 1962 with Grenache and Lladoner Pelut vines at an altitude of 433 meters—hence, the name. Lladoner Pelut is a natural mutation of Grenache which reaches phenolic ripeness sooner and produces wines with a lower alcohol content; it is more commonly used in the wines of Priorat, Catalunya. It offers delicate notes of crushed stone, cranberries and fresh herbs in a silky package with hints of orange zest and rose hips.

VdF Roussillon-Corbières, Domaine Yohann Moreno ‘GS’ 2021 red ($31)

A fun, ‘glou-glou’ style of light Grenache and Syrah; a crunchy core of candied blueberry is offset by a bit of minerality.

Corsica

Corsica has been described as penumbral Italy and Sardinia’s French twin, although in fact, it is very much a wine-producing appellation with its own native soul. Corsicans are imbued with a vehement sense of pride and independence, born in part from perpetual watchfulness: As winemaker Christian Giacometti shares, “The reason our villages were never near the sea is that the Corsicans were always fending off invaders.”

Corsican vignerons work with a roster of seemingly unpronounceable varieties like Sciaccarellu, Biancone and Paga Debiti. In the past couple of decades, these sumptuous, spicy wines have found a growing patronage among those of us in the west eager to learn more about a peripheral Mediterranean gem and these island wines, created without France’s intellectualism or Italy’s numbing regulations and crowd-pleasing varieties, opting instead for face-value frankness and above all, native grapes.

$117 Red & White Corsica Trio: Patrimonio, Corse Figari

Patrimonio, Domaine Santamaria 2018 red ($37)

100% Nielluciu from 25-year-old biodynamic vines grown in a microclimate meliorated by the Ligurian Sea, where soils are (unlike much of Corsica) largely composed of chalky clays and limestone. The grapes are hand-picked and fermented on native yeast, then bottled without fining. Patrimonio is the first AOP in France to forbid chemical weeding; the wine shows cranberry and raspberry with a touch of earthy minerality and spice.

Corse Figari, Clos Canarelli 2016 red ($45)

The soils of the Figari AOP make up France’s southernmost wine region, and it is maintained by many that this bottling represents the best profile of the Sciaccarellu grape to be found. The bright sunshine and granite soils of the southwest part of the island are a perfect cradle for the grape and the wine shows it’s characteristic herbal spice behind soft berry notes and easy tannins.

Patrimonio, Clos Marfisi ‘Ravagnola’ 2020 white ($35)

Vermentino (known in Corsica as Vermentinu) shows off its island expression as floral, with bright flashes of citrus and an almost salty finish, quite reflective of the clay, chalk and schist soils less than a mile from the sea.

A Gift That Keeps On Giving

Membership To ‘The Champagne Society’

Bimonthly Subscription

Not only is Champagne the quintessential drink of celebration, it has traditionally been a gift given with ramped-up sentiments. This year we are offering a couple of variations on this theme, beginning with an opportunity to gift a special someone a six-month or twelve-month membership to The Champagne Society. Our pick for December will be packaged in a wrap-ready gift box along with a congratulatory certificate explaining what lies ahead in bi-monthly installments. For more information please visit our website page: A Holiday Gift: ‘The Champagne Society’ Membership 6-Month ($299) or 12-Month ($589) Subscription.

Not only is Champagne the quintessential drink of celebration, it has traditionally been a gift given with ramped-up sentiments. This year we are offering a couple of variations on this theme, beginning with an opportunity to gift a special someone a six-month or twelve-month membership to The Champagne Society. Our pick for December will be packaged in a wrap-ready gift box along with a congratulatory certificate explaining what lies ahead in bi-monthly installments. For more information please visit our website page: A Holiday Gift: ‘The Champagne Society’ Membership 6-Month ($299) or 12-Month ($589) Subscription.

Elie

- - -

Posted on 2023.12.15 in France, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

Burgundy’s Wealth Of Riches: Shopping List Of Thirteen Packages Of Red ‘Premier-Cru vs. Village’ Pairs To Gift Wine Lovers, Or Explore. Thirteen Intrepid Producers In Thirteen Côte-d’Or Communes.

We can accept that each plot of land on earth is handed a certain microclimate, and whereas climate change may alter some aspects of its character, an acre’s terroir is written in stone… and soil, and elevation, and exposure. But it is very much a human endeavor to make the most of every hand we are dealt, and as such, although the complex and highly-specific Burgundian classification system rarely offers upgrades for loyal service, the efforts of winemakers, combined with changing weather patterns, often raises the bar in areas deemed Village-level rather than Premier Cru to create wines that are superlative.

In this week’s overview, we will take a look at the similarities and differences in a few familiar names when they set their mind to producing a bottling from various hallowed plots of Burgundian territory, both Village-designated and those that wear the Premier Cru label.

Take advantage of these Holiday Packages to explore and discover; treat yourself to a unique opportunity to try several of these appellations—Village level and Premier Cru level—side by side, or gift an example to a wine-lover among your circle of friends and family.

The Notion Of Terroir: Earth Is Given Voice

Above all, terroir is a concept; a flight of vinous fancy that insists a wine’s taste and aroma reflect its place of origin. This reflection may be subtle or overt, but there’s plenty of science behind it. Terroir includes specific soil types, topography, microclimate, landscape characteristics and biodiversity—all features that interact with a winemaker’s choice of viticultural and enological techniques.

Every square foot of earth that supports a vine has its own unique terroir, and wine appreciation is founded on the principal that not all terroirs are created equal. Thus, we find the hyper-division of vineyards sites from the most broad to the narrowest—some named climats are only a few rows in size, but produce wine markedly different than their neighbors. In Burgundy, this obsession with small, precisely delimited parcels is probably more defined than anywhere else, and we will always seek out the best of those wines and share as much information about the vineyards as we can unearth… pun intended.

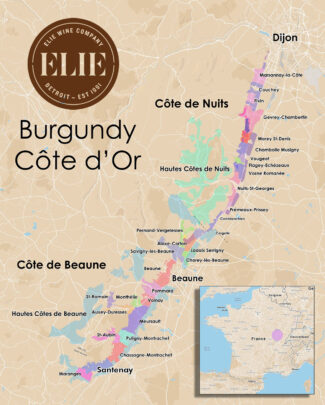

Decoding The Burgundy Hierarchy

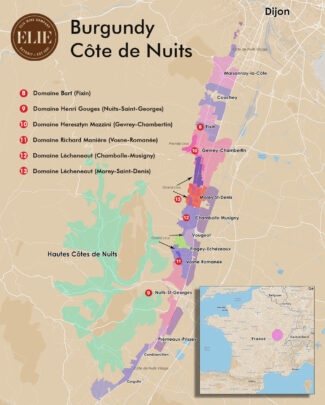

Nowhere does terroir count more blatantly than in Burgundy’s classification system, which has four distinct levels, Grand Cru, Premier Cru, Villages and Régionale, divided up into 84 separate appellations.

Grand Cru, the top of the pyramid, represent less than 1% of the region’s total production. All of the white Grand Crus are today found in the Côte de Beaune, while all of the red Grand Crus (with the exception of the Corton family) are found in the Côte de Nuits. To be consistently exceptional requires exceptional strictures; besides being the favored sites geographically, Grand Cru wines are made with a specified grape variety from a regulated patch of land, from vines of at least 3 years of age and below a certain maximum yield per unit area of land.

Premier Cru wines account for another 5% of Burgundy’s total production, and as such, is only a slightly larger drop in the bucket. There are a few that may outperform Grand Cru wines, but they are priced accordingly. The majority of Premier Crus are from named vineyards, and the climat name will appear on the label. For example, Puligny-Montrachet Premier Cru Les Folatières assures you that this wine comes from the Folatières vineyard in the village of Puligny-Montrachet.

Village level wine is a broad and encompassing swath of terroir recognition, but it is undeniably describable: Savigny is meaty, Volnay is elegant, Vosne-Romanée is spicy, Meursault is nutty. Wines at this level have a slightly higher allowed yield per hectare, but the varietal requirements are the same. This is a slot where Burgundy’s best bargains fit; any vineyard site, Grand Cru or Premier Cru can go into a bottle labeled only after a village. Although it might sound counter-intuitive for a domain to do this, it isn’t. Wineries declassify Grand Cru and Premier Cru wines frequently, and for a variety of reasons.

Régionale wines represent the bulk of wine produced in Burgundy; they are generic, have much more relaxed standards for yields and grape types. They may be labeled Bourgogne Rouge, Bourgogne Blanc, Bourgogne Pinot Noir, Bourgogne Chardonnay or Bourgogne Aligoté—even Bourgogne Passtoutgrains, which is Gamay mixed with a lower percentage of Pinot Noir.

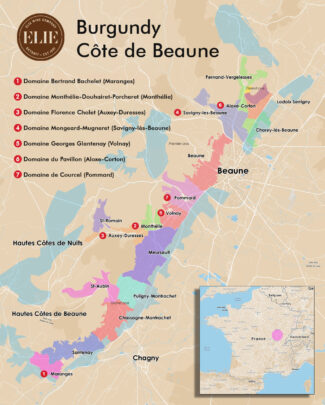

Côte de Beaune

A Myriad Of Soils And Microclimates

A mnemonic device for remembering which shade of wine is best represented by the two subdivisions of the Côte d’Or, the Côte de Beaune and the Côte de Nuit: Bones are white, and the greatest of the Chardonnay-based white Burgundy (Corton-Charlemagne, Montrachet, et al) are from Beaune. Night is dark, and the greatest Pinot Noir-based reds (La Romanée-Conti, Chambertin, et al) come from the ‘Night Slopes’—the Côte de Nuit.

Of course, the two regions make wines of either color. The Côte de Beaune is the southern half of the Côte d’Or escarpment, hilly country where, like the bowls of porridge in Goldilocks, the topsoils near the tops of the elevation are too sparse to support vines and, in the valleys, too fertile to produce top quality wine. The Goldilocks Zone (the mid-slopes) are where the Grand and Premier Cru vineyards are found, primarily at elevations between 720 and 980 feet. Drainage is good, and when vines are properly located to maximize sun exposure, the greatest Burgundies thrive and produce, year after year. The lesser, often forgettable Burgundies (generic Bourgogne) comes from the flatlands beneath the slopes; the fact that these wines are also made from Pinot Noir and Chardonnay is indication of why terroir matters. Likewise, the narrow band of regional appellation vineyards at the top of the slopes produce light wines labeled Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Beaune.

$91 Maranges Village vs. Premier Cru

f the name ‘Maranges’ (at the southern tip of the Côte de Beaune) strikes you as unfamiliar, it’s understandable: It has only existed as a stand-alone appellation since 1988 and encompasses the three villages of Cheilly-lès-Maranges, Dezize-lès-Maranges and Sampigny-lès-Maranges, just west of the more well-known village of Santenay. It is situated in storybook countryside referred to by Burgundian writer Henri Vincenot as ‘gentle and warm-hearted, where the old-fashioned homes of the winemakers provide perfect subjects for a painter’s brush.’