Saint-Julien Channels Pauillac In Search of Purity, Precision and an Assertive Style, Bordeaux’s Château Ducru-Beaucaillou Achieves All in Their 300th Vintage Release, 2019 (3-Bottle Package $366)

If ever an estate has enshrined within its very name the fact that grapes thrive where other crops fail, it is Château Ducru-Beaucaillou: The famous lieu-dit of Beaucaillou (good pebbles) was once called Maucaillou (bad pebbles) when they tried to grow cereal crops instead of grapevines. It is the deep Günzian gravel that earns the terroir both scorn and praise from farmers (depending on crop; along with soil, a favorable climate and the general wherewithal of generations of vignerons, Ducru-Beaucaillou’s reputation has held strong—and grown—for three centuries. Vintage 2019 marks this very milestone and the estate’s outspoken owner Bruno-Eugène Borie considers it a spectacular vintage in which the château’s legendary purity, precision and assertive style is on full display.

This week’s package offers a fascinating peek behind the curtain at Ducru-Beaucaillou to see how climate change has restructured priorities and bred innovation, and how the leadership of Bruno Borie has led to a number of incredible undertakings, including re-corking a full inventory of 40 vintages (1950 and 1990) in an oxygen-free environment, giving them an extended life of 50 more years.

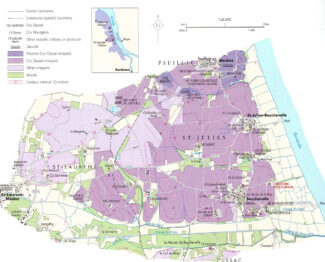

Saint-Julien & Pauillac: Neighboring Communes

The most singularly revered appellation on earth, Pauillac is to wine what The Beatles are to pop music. Though fewer than ten square miles in total, three of the top five châteaux in the 1855 Médoc Classification are located here, and so varied is the topography that each estate is able to market the individual nature, in style and substance, of their wares. And it is this trio of skills—growing, producing and selling—that has made the region almost a cliché, synonymous with elite wine, where futures sell for exorbitant rates long before the wine is even in the bottle.

Great things come in small packages, especially when big money is involved. Saint-Julien—the smallest of the major Médoc appellations at under four-square miles—also boasts (through a series of real estate deals between the large estates and the small ones) an astonishing pedigree: Fully 95% of the appellation sits on classified acreage. Key to the desirability of the wines produced here is the seamless fusion of concentration and elegance; the wines are of a style historically referred to as masculine, but held to standards of manhood in the mode of a Knight Templar before a brawny warrior. This blend of finesse and fortitude comes in part from the preponderance of gravel in the best vineyards, allowing natural drainage in the wet years, radiating warmth in cool vintages, extending the growing season and allowing vine roots to extend

omne trium perfectum

300th Vintage Release: Three-Bottle Package ($366)

The estate’s 300th anniversary was blessed with magnificent growing conditions, which brought forth a wine of particular distinction. Ideal levels of rain (falling mostly at night, guaranteeing freshness) while clear days and cool nights in September, together with a heatwave in the middle of the month, helped to concentrate the fruit and ripen the very fine tannins.

The wine package we offer this week includes one bottle of the special Tercentenary bottling of Château Ducru-Beaucaillou 2019, one bottle of 2019 ‘La Croix Ducru-Beaucaillou’ which hails from a separate vineyard and yet is considered one of the best second labels in the business and one bottle of Ducru’s third wine ‘Le Petit.’

Château Ducru-Beaucaillou

Passion Perfects Nature’s Opus

Beside the poetry in a rhyming name, this hallowed Second Growth estate, given high praises in the 1855 classification, has produced the best wines in its history in the 21st century. This is credit to the Borie family, who bought the château in 1941.The current helmsman is Bruno, who grew up on the estate: “I was born and raised at Beaucaillou and I have always been immersed in this country landscape and lifestyle, in the vineyards and the pastures, cattle and all; I basked in the fascinating environment of the cellars, where the transmutation of the grape juice into wine, and then the slow maturation of the young wine into these magical elixirs takes place.”

He learned the magic of wine early, but to nail down the business and technical end, he spent time in California as a winery intern before becoming the Commercial Director for P.A. Sichel and the CEO of Lillet, the Bordeaux aperitif. He began to manage Beaucaillou in 2003, where he was instantly confronted with the excessive heat the Bordeaux had begun to suffer with global warming. This required that he embark upon a paradigm shift to tackle the changing climate, and it perseveres to the day: “My first major decision was to not have a preconceived agenda,” says Bruno, “but rather to listen to nature and try to tailor our approach accordingly. For 2003, this meant very little leaf thinning to keep bunches shaded and protected from the scorching rays of the sun.”

These days, Borie relies on a number of quality initiatives, including more selective harvesting and establishing more organic farming practices: “We now cultivate and plough various grasses and legumes to help aerate the soil,” he explains. “This increases biodiversity, and the quantities of critical nutrients. When replanting vineyards, we leave our plots fallow for five years, during which time we perform a deep ploughing to reduce compaction, and then cultivate various grasses in rotation to help preserve our precious soils.”

The Vineyard: Maucaillou, Beaucaillou

The clock began to tick towards Château Ducru-Beaucaillou’s tercentennial hurrah in 1720, when Jacques de Bergeron married Marie Dejean, whose dowry included land known as Maucaillou, a name formed as a portmanteau of the French words ‘mauvaise’ and ‘cailloux’ meaning ‘bad pebbles’. The first records of the name change from ‘bad’ to ‘good’ is 1760.

The titular stones, good or bad, are quartz pebbles swept in by the ancient Garonne river at the beginning of the early Quaternary Period, about two million years ago. Beyond the gems it produces in the cellar, terroir so blessed also offer rich lithological finds like Lydian jasper and agatoids. The gravel is less kind to plants, giving rise to poor soils—a condition to which grape vines are well suited. Their vast network of roots, snaking through the gravel, are able to draw nutrients from far below. A bonus is that in cooler weather, the stones retain daytime heat and return it to the vines at night to facilitate the ripening of the grapes.

Ducru-Beaucaillou’s proximity to the vast Gironde River estuary—where four daily tides mitigate the rigors of winter and moderate the summer heatwaves—may also deflect the trajectory of hailstorms. The vineyard is located to take advantage of these natural features, beginning immediately above the low-lying marshland of the Gironde, about three hundred yards from the estuary and extending to the west, ending at a slight elevation that offers natural drainage of rainwater into the Gironde or the tiny Mouline brook to the north.

Bruno Borie: Works To Balance Centuries Of Tradition With Contemporary Viticulture

“I was born in 1956 and raised in Ducru-Beaucaillou,” say Bruno Borie. “I was truly a country boy, preferring to run through vineyards and meadows than taking walks in the town. I enjoyed the company of the winegrowers and loved taking part in the various jobs, including, of course, the harvest.”

Bruno-Eugène Borie, Château Ducru-Beaucaillou

In his years exploring the vineyard as a living entity as well as a financial concern, Borie has developed a deeply personal philosophy about his role: “We help the vineyard give birth to wine. Nature can do it all; we are here to allow nature to express and share the best of herself. I am here to make Ducru-Beaucaillou, not just another Cabernet Sauvignon or another Cru Classé.”

To this end, he has overseen significant changes in Beaucaillou viticulture, introducing new techniques and reviving forgotten practices, looking both towards the past and modern science. Although he considers biodynamics to be more esoteric than scientific, the entire vineyard was certified HVE 3 in 2016 and he eschews the use of herbicides and pesticides. Emmanuel Bonneau joined the team as technical director in 2016, and is currently researching phytotherapy (the medicinal use of medicinal plants and herbs) to tackle mildew, while lightweight robots reduce soil compaction.

“The most crucial element in making fine wine is to be close to the plant and its ecosystem,” Bruno explains. “Our system of pruning, for example, consists of preparing the vine not only for next year, but following ones. Therefore, it must be the same person who prunes from one year to another because he ‘reads’ each vine the same way. Each of our vignerons is assigned a selection of plots for all seasonal vineyard operations which fosters a deeper connection with the vines through continuity. This ensures that our approach is the most adapted for our environment and our vines.”

The Harvest: The When And Why

The decision of when to harvest is a complex one, and it would be fair to say that every estate has their own formula though which they determine picking schedules, based both on weather and the style of wine they’re after. It’s no different at Beaucaillou, where, according to Bruno, “We pick each plot when fruit is at optimal ripeness and then seek to preserve its purity and enable it to express its terroir fully. We also consider blending compatibility for harvest date. For example, the 5-15% of Merlot in the blend of Ducru needs to be Médoc-like in style. It must be compatible with Cabernet with typicity, freshness and elegance to counterbalance Merlots that are overly rich. To determine the precise harvest date for each plot, we collect and analyze the critical measures (sugar, IBMP, acidity, pH), but the final decision is based entirely on taste.”

Winemaking: Selection And Precision

A combination of artisan methods and new innovations form the backbone of Château Ducru-Beaucaillou’s cellar tenets; leading the second category is the use of conical wooden ‘Smart Vats’ for the Grand Vin. Smart Vats have a number of advantages, including automatic and gentle remontage that can be fractioned over 24 hours with complete oxygen control for extreme precision, analyzing and storing relevant data on sugar, density and oxygen throughout cuvaison, allowing a refinement of approach and data saved for current decisions and future reference.

The traditional methods that Borie employs includes ‘slow hand’ extraction: First come a cold maceration, then gentle remontage in the earlier phases of fermentation when critical decisions are made by taste and tanks are sampled several times per day. The goal, according to Borie, is the extract noble tannins with the most refined grains, giving the ‘draped cashmere’ mouthfeel for which Ducru-Beaucaillou is widely praised.

“Of course, we consider the data,” Borie says, “and Smart Vats enable us to conduct our extractions with even more precision to achieve this goal. In the end, science allows us to make better art.”

2019 Vintage: Low Yields But Pure, Aromatic And Well-balanced

Like much of the Left Bank, the 2019 growing season for Saint-Julien began with a mild, if lackluster spring that saw cool temperatures and patches of rain in the run-up to the summer months (although rainfall was still less than in other Bordeaux appellations, leading to lower yields than average). A warm, dry summer ensured the grapes reached phenolic ripeness and, bar some rainfall towards the end of the season, conditions remained smooth and easy for a seamless harvest.

The resulting grapes were extremely healthy, and naturally, this translates to the wines. In general, the wines are sophisticated and powerful with rich, dark fruit and velvety tannins while still retaining delicate aromatics. The best 2019s exhibit the ideal balance between fruit, acid, alcohol and tannin needed for long-term aging. Although many of the wines will make very pleasant early drinking, the top examples should be able to cellar for many years to come.

2019 At Ducru-Beaucaillou: Cabernet Sauvignon Is Key

So hot was the summer of 2003—the year that Bruno Borie took over Ducru-Beaucaillou—that he knew that winemaking in Bordeaux would likely never be the same. Going forward, weather, rather than tradition, would dictate work in the vineyard. Harvest dates were creeping forward and August vacations were a thing of the past. 2019 was another hot season, and Bruno realized that this sort of weather pattern was ideal for Cabernet Sauvignon, a thick-skinned variety that requires a lot of accumulated heat and sunlight hours to fully ripen.

He says, “With warmer summers like 2019, the fruit is richer and more concentrated with longer length, and the thick skins, which ripen during the final phase, can fully ripen, giving deeply colored wines with high levels of extremely fine-grained, ultra-silky tannins. At Ducru, we have three key strengths as we face climate change: privileged terroirs, the dominance of Cabernet Sauvignon, and of course highly invested and competent technical teams, including Cellar Master René Lusseau and Oenologist Consultant Eric Boissenot.”

2019 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($261) ONE BOTTLE

2019 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($261) ONE BOTTLE

80% Cabernet Sauvignon and 20% Merlot matured for 18 months in 100% new French oak. Purple-black in color, the 2019 Ducru-Beaucaillou explodes from the glass with notes of cassis, blueberry pie and plum preserves behind hints of candied violets, dark chocolate, licorice, crushed rocks and freshly-overturned soil with a touch of mossy bark—a wine whose finish passes the 60-second mark with ease.

2019 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou ‘La Croix Ducru-Beaucaillou’, Saint-Julien ($60) ONE BOTTLE

2019 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou ‘La Croix Ducru-Beaucaillou’, Saint-Julien ($60) ONE BOTTLE

The estate does not market La Croix Ducru-Beaucaillou as a ‘second wine’ because it comes from a different source: an inland vineyard on the south bank of the La Mouline stream close to Château Talbot; it was previously sold as Château Terrey-Gros-Caillou. It consists of 91 acres planted with 65% Cabernet Sauvignon, 25% Merlot, 5% Cabernet Franc and 5% Petit Verdot. The breeding is made for 60% in new oak barrels 12 months, producing a muscular yet fresh wine, displaying a full range of berry, lavender rose petal, mint, spice and gravel inflections.

2019 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou ‘Le Petit du Ducru-Beaucaillou’, Saint-Julien ($45) ONE BOTTLE

2019 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou ‘Le Petit du Ducru-Beaucaillou’, Saint-Julien ($45) ONE BOTTLE

60% Merlot Noir, 36% Cabernet Sauvignon, 4% Petit Verdot barrel aged for twelve months with one-third new oak. Among the most sumptuous third wines on the market, intended as an introduction to the Famille Borie style, but in fact an intense experience that stands on its own. The wine is lush with layers of dark cherry, plum, mocha and licorice; a bit of aeration also brings out hazelnut and walnut wrapped in creamy tannins.

Time Capsules

A Half-Century of Ducru-Beaucaillou

As Bruno Borie carefully recorked all vintages between 1930 and 1990, this divine diorama looks at some of the top vintages from the estate of the past half-century—so many, in fact, that it frequently said that Ducru-Beaucaillou is a Second Growth that deserves First Growth status.

2010: A Promise of Longevity

Recognized as legendary across the board, 2010 was truly great vintage whose exceedingly dry growing season served to concentrate the juice and provide wines with outstanding depth.

Despite a wet June giving a damp start to summer, the season soon heated up turning exceedingly hot and dry, particularly in the Médoc region; the arid conditions caused the right amount of water stress to improve the berries, and the long, sunny days continued through to October with nights steadily chilling as the season drew to a close. Cool nights were imperative to preserving the acidity in the grapes and rains, fortunately, came in September freshening the grapes.

2010 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($550)

2010 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($550)

Just beginning to fully open up, the wine is now entering a drinking window that should last two more decades at least. A sensuous nose offers layers of blackberry paste and warm ganache, steeped fig and pastis-soaked plum flavors. The structure is massive yet polished, and the fruit displays purity through a graphite-supported finish. Large-scale and extremely well-rendered. 8,416 cases made.

2000: A Stunning Vintage, Closer To Maturity

A mild, warm winter followed by a wet spring made mildew a threat, but from July onwards, a spectacular summer dominated Saint-Julien with hardly any rain until mid-September. Sunny weather then returned for the October harvest, broken by a single day of rain—a boon to parched vines. Producers who picked early risked unripe wines and others who picked later risked jamminess, but for the majority who picked at the right time, the vintage offers fantastic rewards.

2000 Château Ducru Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($490)

2000 Château Ducru Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($490)

70% Cabernet Sauvignon and 30% Merlot, the truly stunning garnet-brick colored 2000 Ducru-Beaucaillou offers flamboyant scents of baked black currants, raisin cake, prunes, Chinese five spice and eucalyptus plus touches of cigar box, new leather and cast iron pan. It will continue to improve, too.

1983: Fully Mature

1983’s growing season in Saint-Julien began with a cold winter and chilly, wet spring. Balmy conditions settled in shortly afterward, allowing for a near-perfect budburst and flowering, and, despite a brief cool patch, temperatures than rocketed in July with the month even proving a record breaker. Drought was a problem but only through August, which brought plenty of rain. September brought drier, sunnier conditions and a run of good days in the lead-up to the harvest ensured the resulting crop was in good health. The harvest began towards the end of September and ran through to October, producing a generous but good-quality crop.

1983 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($2,400) DOUBLE-MAGNUM

1983 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($2,400) DOUBLE-MAGNUM

Although some ‘83s lacked the structure for long term again, large format bottles age at a much more leisurely pace, and thus, are ideal to experience the nuance changes in this full-bodied wine showing blackberry and hazelnut behind a beautiful base of gravelly soil tones, cigar ash and a touch of juniper berry. Perhaps currently drinking at its apogee, the wine is svelte and pure on the attack with melting tannins and a long, complex and seamlessly balanced finish

1978: The Miracle Vintage

Known as the ‘Miracle Vintage’, 1978 began with a damp, chilly spring that affected both bud break and flowering. Conditions eventually improved, but it was not until the end of the summer the weather had sufficiently warmed up and dried out. There followed a string of idyllic, sunny days, perfect for bringing the crop to phenolic ripeness and these perfect conditions late in the season rescued the vintage from possible disaster—the so called ‘miracle.’ The heavy rains of October came late, holding off until all the fruit had been picked—another manifestation of the miracle.

1978 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($450)

1978 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($450)

‘78 Ducru is considered one of the unequivocal successes from this vintage. From the outset, the well-developed bouquet of licorice, earth, black currants, and underbrush shone none of the vegetal character found in many wines of the vintage. Now fully mature, the medium-bodied Saint-Julien gem exhibits soft tannin, excellent concentration and purity, and a sweet, elegant finish.

- - -

Posted on 2025.04.15 in Pauillac, Saint Julien, France, Bordeaux, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

Rioja Alavesa: Going Its Own Way New-Generation Viñadores Emphasize Vineyard Over Cellar Treatment and Show the Specialness of Thier Sub-region.

There are no philosophical mandates in winemaking, but there are certain truisms that seem to arise regardless of appellation and country of origin. That is, low-end wines tend to emphasize immediacy; they display linear, fresh fruit notes unhindered by the sort of essential inner structures that can evolve into something else—something more interesting.

Pricier wines are faithful vessels for a specific time and place.

No dusty tome on why certain wines improve, or become more complex with age, does justice to the words of Luis Gutierrez in his book ‘The New Vignerons’ as he describes a tasting with one of our featured winemakers, Telmo Rodríguez of Remelluri:

“In 2015, I returned to Remelluri to talk to Pablo and Telmo about all this, to taste their new vintages and reminisce about that dinner in 1998, once again eating some of the most typical dishes from La Rioja in front of the huge fire in the kitchen. We had Patatas a la Riojana (Rioja-style potatoes), ribs, and spring onions from their vineyards. And we drank a superb 150-year-old-plus Madeira, a wine that made us travel in time and think about the people who had made it, people with no means, and we imagined how they must have lived, possibly without electricity or shoes. They would have never dreamt that someone in Spain would be drinking that wine a century and a half later. We were there at Remelluri the day after a heavy snowfall, the heaviest they had seen since 1999, one of those days when you have to take photos of snowy vineyards that have to last for the next ten years.”

The Ascendency of New Generation: Setting the Path to the New Rioja

When a generational shift overtakes an old, familiar wine zone, the first casualty is often conditioning. In days of yore, Rioja meant big, blustery, barrel-bludgeoned reds, where quality was measured by ‘crianza’—the years a Tempranillo blend spent first in oak, then in bottles. The farther the wine was away from the vineyard, the better it was supposed to be. Entry level Crianza wines undergo a two-year old process which keeps them at least a year in fifty-gallon barrels. Riserva sees three years of aging; Grand Riserva, five-years, with at least two years in oak. These wines are, by intent, filled with complexity, with the oldest displaying matured tertiary flavors of tobacco, leather, truffle, etc.

It’s a style of wine has its legions of apostles, but in a general sense, freshness over oak and a sense of place rather than a sense of wood is the name of the game in the modern era. Less ripeness is traded for more bracing acidity. Rioja may have been a bit slow to get the memo, and wine drinkers in America even more so, but the new wave of younger winemakers in Spain’s most famous wine-producing region are spreading the wings of innovation so wide that we can’t help but feel the influence.

In this package, we will feature five bodegas run by five charismatic winemaker who are offering a fresh take on an old style, breaking with tradition and frequently loosening the Tempranillo stranglehold in favor of a cornucopia of other varieties.

Rioja Alavesa: Finding the New in an Old Land

To level set, Burgundy contains 70,000 acres of vineyards divided into 84 distinct appellations. Rioja, with 161,424 acres, has three—Rioja Alavesa, Rioja Alta and Rioja Baja—and even those rarely appear on labels. Instead, the traditional way of categorizing wine from this sprawling blend of Mediterranean and mountain landscapes, has been a celebration of how long the wine has spent in wooden sarcophagus, from the youngest Joven styles through Crianza, Reserva and Gran Reserva. The aging is carried out in 225-litre oak barrels for a period ranging from 1 to 3 years, and later in the bottle itself for a period between six months to 6 years.

This is largely the doing of the Consejo Regulador, the Regulatory Council of La Rioja, whose mission is to safeguard the region’s identity—a noble enough pursuit, whose result has traditionally been an ocean of largely homogenous wine: Silky, moderately potent, often displaying lackluster fruit with a patina of age. Under current rules, Rioja is often blended from vineyards across the entire territory, and the barrel is, perhaps, given more emphasis than the grapes.

Says winemaker Gil Berzal of the eponymous bodega in the Rioja Alavesa: “Rioja has forgotten its roots and it gives the prominence to the barrel, basing its attributes in the presence of the wine in touch with the wood. Our area is different from the rest of areas included in the D.O. Rioja, due to the characteristics of the soils, climate, age of the vineyards, and the relief of the land. This is the reason to give Rioja Alavesa its worth.”

Berzal is a pioneer of the new thinking afoot in Alavesa, a hilly region along the north bank of the Ebro River full of chalk and limestone, ideal for growing the mainstay grape, Tempranillo. Iconoclastic winemakers like Álvaro Loza, Arturo de Miguel Blanco, Olivier Rivière and Telmo Rodriguez have pioneered technical advances and field techniques designed to rise above the rusticity of the region’s wines, and at least one consortium, the Asociación de Bodegas de Rioja Alavesa has gone so far as to explore the formation of an entirely new DO that would allow Alavesa producers to include information on the label that reflected terroir, lot and the winemaking process.

Álvaro Loza

Rioja Alavesa

‘A Declaration of Intent’

Talent occasionally skips a generation. Case in point is Álvaro Loza, who grandfather raised vines in the hills of Rioja but whose parents are not in the business at all. When Álvaro took his grandfather’s lessons to heart, that wine is “all about happiness and joy,” he quickly learned that a whole lot of experience is also required to make a complete package. As such, he realized (in the nick of time) that he should switch his studies from mechanical engineering to oenology, and having completed his schooling in Beaune’s famous wine school, Álvaro set out on a series of jaw-dropping internships. First in Napa, where he worked the harvest, then back to France where he worked with a small producer in Condrieu. In 2018 he travelled to Tasmania, and in 2019 he took a job at Domaine Léon in the Côte des Bar (Champagne), before joining the harvest at Clos Ibai in Rioja, where he made his first wines. Since then, he has moved between hemispheres, harvesting with Marlise Nieman in Bot River (Cape South Coast, South Africa) and picking grapes in Champagne and Rioja. Working at Clos Ibai has allowed him to have a tiny space in this cellar for his wines.

Álvaro Loza

“I still farm the four plots of land that my grandfather tended—they have become the cornerstone of my wine business. I farm two parcels in Haro and two in Labastida, totaling just three acres altogether. Of the Haro vineyards, one is goblet-trained, the other trellised are in the Zaco meander, next to the river Ebro. They combine a sandy area with another rich in pebbles. The Labastida plots are located on the same terrace between Cien Reales and Las Viñuales, where the most striking feature is a large layer of sandstone with calcium carbonate sediments.”

According to Loza, this soil contributes to obtaining the fresh tannins that characterize his wines wine and prolong the finish. With the exception of some white grapes and a mixture of varieties in the oldest vines, Tempranillo is the dominant variety. Álvaro Loza cultivates the land with the philosophy of maintaining the oldest and most special vines that reflect their potential in the wines.

“This is a global trend,” he points out, “and one that can extend to my homeland. These types of small vineyards would be of no use to the region’s larger producers, and so by maintaining them we can not only ensure that old vines are not lost. Vinifying them is key to making the kind of wine I most appreciate.”

Álvaro Loza Viticultor, 2021 Rioja Alavesa ‘Labastida’ ($53)

Álvaro Loza Viticultor, 2021 Rioja Alavesa ‘Labastida’ ($53)

95% Tempranillo and 5% Viura. Álvaro’s Labastida plots are located on the same terrace between Cien Reales and Las Viñuales, where Its most striking feature is a large layer of sandstone with calcium carbonate sediments. According to Loza, this soil contributes to obtaining the fresh tannins that characterize the wine and help to prolong the finish.

165 cases made.

Álvaro Loza Viticultor ‘Cien Reales’, 2021 Rioja Alavesa ‘Labastida’ ($87)

Álvaro Loza Viticultor ‘Cien Reales’, 2021 Rioja Alavesa ‘Labastida’ ($87)

100% Tempranillo. A scant 24 cases were made of this highly-prized single-plot wine. The Tempranillo is hand-harvested and 70% of the fruit is destemmed, and the remaining 30% is left whole-cluster, where it ferments in the open air during a 35 day maceration. Following a pressing, the wine is racked to 225 liter neutral French oak barrels for 16 months before bottling.

Arturo de Miguel Blanco

Artuke

Rioja Alavesa ‘Baños de Ebro

Vineyards are Judged on Their Potential

“We fight to preserve our culture, not to transform it,” announces Arturo de Miguel Blanco.

With his brother Kike (who joined him in 2010—‘Artuke’ is a portmanteau of both their first names), he cultivates about fifty acres of decades-old, high-elevation vineyards in Baños de Ebro in Rioja Alavesa. Working with blends of Tempranillo, Garnacha, Graciano, and Mazuelo (and often with white grapes in the mix) they are creating the sort of bright, fruit-and-mineral driven wines that best mirror both their terroir and new trends in Rioja.

Arturo de Miguel Blanco, Artuke

“We buck the norms and also bureaucracy,” he says. “For example, we plant all bush vines, even our newest ones. Government aid goes to trellised vines because they can be mechanized and the yields are larger, but their resistance to water stress is lower. It sadden me to see the loss of old bush vines in this area; they’re being replaced by trellised plants.”

Blanco’s father Roberto produced bulk wine from the same land, but the brothers have seen fit to explore opportunities their soil might provide by doing a detailed study of various plots in Baños de Ebro, Ávalos, San Vicente de la Sonsierra and more recently, in Samaniego. Arturo’s conclusion was eye-opening:

“Rioja should be bottled along regional, village and single vineyard lines, similar to the Burgundian approach, and we should begin to eschew the traditional Crianza, Riserva and Gran Riserva classifications.”

Artuke ‘Pies Rotos’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa ($24)

Artuke ‘Pies Rotos’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa ($24)

85% Tempranillo, 15% Graciano from middle-aged vines, 20 to 50 years old, grown on the alluvial soils of Baños de Ebro. Fermented on destemmed but uncrushed grapes in the carbonic maceration style; aged one year in 500-liter oak barrels, although 10% of the volume was preserved in concrete. ‘Pies Rotos’ means ‘broken feet.’ A nicely fresh evening sip with added complexity from the oak; it shows bright cherries and acidity due to the elevation of the vines, and picks up the licorice notes found in many quality Riojas.

Artuke ‘Finca de los Locos’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa ($40)

Artuke ‘Finca de los Locos’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa ($40)

The name is a nod to Arturo’s ‘loco’ grandfather, who bought a neglected plot of land in Baños de Ebro and vowed to make productive—which he did. 80% Tempranillo and 20% Graciano, the fruit comes from the single plot ‘Las Escaleras’ planted in 1981 on sandy limestone soils. The wine is ripe and juicy, bright with red berry acidity and balsamic herbs.

Artuke ‘Paso las Mañas’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa ($50)

Artuke ‘Paso las Mañas’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa ($50)

100% Tempranillo from a ten-acre plot of Tempranillo on the highest slope of Samaniego (at an altitude of 2500 feet) where the wind blows so relentlessly that the vines had to be specially trained, unlike the head-pruning that Arturo uses in the rest of his vineyards. Soils are clay and chalky soils with many surface stones; the grapes are fermented and aged in used French oak foudres, resulting in a wine loaded with creamy black cherry complemented by a hint of blackberries, sweet spices, and herbs.

620 cases made.

Artuke ‘El Escolladero’, 2020 Rioja Alavesa ($120)

Artuke ‘El Escolladero’, 2020 Rioja Alavesa ($120)

tiny production wine, less than one thousand bottles made. And understandably so, since the grapes come from the Escolladero (derived from the Spanish word for obstacle) vineyard in one of the most difficult passages through the Sierra Cantabria mountains. 85% Tempranillo and 15% Graciano planted in 1950; the grapes are vatted in micro-tanks and undergo daily punching down and pigeage, then spends 12-16 months in 600-liter French oak barrels. The wine remains very fresh with luscious notes of bramble berries and coastal herbs behind nicely integrated tannins.

Artuke ‘La Condenada’, 2020 Rioja Alavesa ($150)

Artuke ‘La Condenada’, 2020 Rioja Alavesa ($150)

80% Tempranillo with a blend of Graciano, Garnacha and Palomino Fino. The grapes are from vines about 40 years old grown on sandy soil at an altitude of about 1800 feet. Harvested by hand and aged in French oak barrels for 14 months, then bottled without sulfur after a soft filtration, it shows dynamic blackberry, cherry and strawberry notes swirling amid toasty vanilla and roast coffee beans with a finish well-balanced with spice and mineral note.

Telmo Rodríguez

Granja Nuestra Señora de Remelluri

Rioja Alavesa ‘Labastida de Álava’

New Single-Origin Rioja

In September, 2021 a wine that had been in the making for almost a decade was released at the Place de Bordeaux. Called ‘Yjar,’ it is a single vineyard cuvée from the foothills of the Sierra de Toloño in Rioja.

The wine was the brainchild of Telmo Rodríguez, who in 2011 returned to the idyllic family estate of Granja Nuestra Señora de Remelluri in Labastida after an 11-year absence. Intent on improving the bodega’s standing in the wine world while introducing ecologically-sound practices (viñedo ecológico, or organic vineyard, is one such example), his first step was to isolated those grapes grown at Remelluri from grapes sourced from long-standing suppliers, sending the latter to Lindes de Remelluri, a village wine range that includes a red wine from San Vicente de la Sonsierra and another one from Labastida.

Telmo Rodríguez, Remelluri

“Remelluri has not been ill-treated since the Middle Ages,” Temo says with pride. “When my parents bought it in the 1960s, it was farmed with animals, fertilized with manure, and grass grew freely among the vines. What’s so special about it is the proximity to the mountains, something that other properties lack.”

Now extending to nearly 370 acres, vineyards stretch across three valleys; the central area known as Remelluri, plus Valderremelluri and Villaesclusa. Soils vary within the clay-limestone sphere at elevations that range from of the Sonsierra. Elevation ranges from 2000 feet to nearly 3000—remarkably high for viticulture. These higher plots are reserved for white varietals.

Remelluri ‘Yjar’, 2018 Rioja Alavesa – Labastida de Álava ($179)

Remelluri ‘Yjar’, 2018 Rioja Alavesa – Labastida de Álava ($179)

Pronounced (more or less) ‘Ya,’ the wine is a field blend of Tempranillo, Graciano, Garnacha, Gran Negro and Rojal. The vineyard, 9 acres in size, sits on an eroded slope with its own water supply patter; the soil contains a high concentration of carbonates, accumulated to a depth of around two feet. The wine is juicy with black cherry, crushed blueberry and cocoa powder that evolve to truffle, black pepper, incense and freshly chopped herbs.

Olivier Rivière

Rioja Alta, Rioja Baja, Rioja Alavesa

Channeling Burgundy

Olivier Rivière’s path to Rioja was hardly one of least resistance: Born in Cognac, he had made up his mind to produce wines in Fitou—the red wine appellation at the heart of southern France’s Languedoc-Roussillon. Having studied oenology in Montagne St-Émilion, he interned in Bordeaux and then in Burgundy, working on a range of vineyards and learning the nuances of biodynamics. This latter skill proved to be his lifeline to Spain; hired by Telmo Rodriguez in 2004 to help convert his La Rioja Alavesa vineyards to biodynamic production, Rivière never left, having fallen in love with Rioja’s diversity of grape varieties and soil types.

Olivier Rivière

“The soils here are made up of red clay, limestone, sand, gravel and alluvial material,” he says, “and the climate is generally mild, typically continental. My harvests are conducted by hand, with grapes transported in 14-kilogram batches to avoid damage, and taken to the cellar for manual selection within 30 minutes. Whole cluster fermentation takes place, each variety separately, using indigenous yeasts, and the wine is aged in variously sized tanks, foudres and demi-muids. Maceration is minimal, and only a small amount of sulfites will be used at the point of bottling.”

Rivière tends to follow a technique of producing cuvées holistically across terroirs and uses a quality grading system imported from Burgundy, starting with generic appellations and village wines, and moving up to Grand Cru; this is in direct opposition of the local tradition of Crianza, Riserva and Gran Riserva. Today, he farms 61 acres with elevations between a thousand and three thousand feet and above sea level. Some of his vines are more than 90 years old, and include Tempranillo, Graciano, Mazuelo, Garnacha, Viura, Malvasia and Garnacha Blanca and cover vineyards in Rioja Alta, Rioja Baja and Rioja Alavesa, as well as his prized plot in Artanza.

Olivier Rivière ‘Las Viñas de Eusebio’, 2015 Rioja Alavesa ($55)

Olivier Rivière ‘Las Viñas de Eusebio’, 2015 Rioja Alavesa ($55)

100% Tempranillo, Las Viñas de Eusebio comes from two sites near Laguardia and Navaridas, unique for their decomposed sandstone and limestone soils. Elevation is high (between 1600 and 2000 feet) and the vines are fairly young at 20 years old. With more age, Olivier believes that these two sites will produce at Premier Cru levels. Amazingly fragrant and densely structured, the wine is beautifully scented with forest berries, spiced plum and balsam wood through the finish.

Olivier Rivière ‘Gabaxo’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa, Rioja Alta, Rioja Baja ($28)

Olivier Rivière ‘Gabaxo’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa, Rioja Alta, Rioja Baja ($28)

‘Gabaxo’ is a vaguely unfriendly term to signify a border jumper, and this wine is, in fact, Olivier’s only wine that blends fruit from various sites within Rioja. The Tempranillo and Graciano are from Rioja Alavesa, planted on rocky, clay-limestone soil at elevation nearly 1700 feet. The Garnacha is from Cárdenas in Rioja Alta, grown on red clay, and from Rioja Baja. Along with Bastid, Olivier considers Gabaxo to be equivalent to Côte de Nuits version of Rioja.

The Other Two Sub-regions: Rioja Baja and Rioja Alta

Despite the innovations happening in Rioja Alavesa, it remains the smallest of the three Rioja regions—wetter and cooler than the other two, boasting predominantly chalky clay with terraced vineyards.

Rioja Alta is located on the western side of Rioja and has an Atlantic climate with soils mostly comprised of iron-rich clay mixed with limestone. Due to the sub-region’s varying elevations, the wines produced here can have great structure and high acidity. The majority of Rioja Alta’s vineyards lie south of the Ebro River. Tempranillo thrives in these conditions, producing signature style of traditional Rioja; as a result, these wines form the backbone of most Rioja blends. Other important grape varieties include Graciano and Garnacha. When compared with Rioja Alavesa, these wines tend to be lighter in body and lower in acid, with the emphasis on elegance.

Rioja’s east is referred to as Rioja Baja, although some now call it ‘Rioja Oriental,’ thinking of ‘baja’ as a pejorative term). In fact, Rioja Baja is primarily fruit tree and vegetable country, and in the 19th century, it was criticized for planting grapevines in highly fertile alluvial soil and as a result, overproducing wine grapes. But since Rioja was traditionally made by blending grapes from all over the region and because Rioja Baja is warmer and drier than the Alta or Alavesa, Baja grapes almost always reach total ripeness, something that happens with less regularity in the other two subzones. Also, Rioja Baja was Garnacha country, adding character in blends to the predominant Tempranillo of the Alta and Alavesa. Sadly, most of the Garnacha has been replaced with Tempranillo since the late 1980s, but Garnacha is still in demand, and some wineries are investing heavily in it or replanting it.

Olivier Rivière ‘Rayos Uva’, 2022 Rioja Baja ($20)

Olivier Rivière ‘Rayos Uva’, 2022 Rioja Baja ($20)

Rayos Uva is Olivier’s version of a Bourgogne Rouge, sourced from fruit grown in the sandy, gravelly and alluvial soils of Rioja Baja. 2022’s blend is biodynamically farmed Tempranillo, Garnacha and Graciano, meant for drinking now, shows raspberry perfume with cherries in the foreground along with light tannins and mineral salts strung across a slender, fruit forward frame.

Olivier Rivière ‘Ganko’, 2022 Rioja Alta ($61)

Olivier Rivière ‘Ganko’, 2022 Rioja Alta ($61)

‘Ganko’—Japanese for ‘stubborn—is Olivier’s nickname. A blend of 60 – to 90-year-old Garnacha and Mazuelo vines grown in sandy red clay at elevations near two thousand feet, it is hand-harvested and whole-cluster fermented on natural yeast in concrete tanks, then aged 16–18 months in foudre and French oak demi-muids. Powerful and full-bodied with intense, spicy red fruit notes ideal for laying down, but enjoyable young with an hour’s decanting.

Benjamín Romeo

Bodega Contador

Rioja Alta ‘San Vicente de la Sonsierra’

‘Even the Smallest Detail Has Its Reason.’

We’re fond of saying cavemen made wine by discovering naturally-fermented fruit while foraging, and then translating that natural happenstance to their rocky shelters. In 1995, Benjamin Romeo, winemaker and vine-grower, joined their ranks when he acquired a centuries-old cave hewn into the rock beneath the Castle of San Vicente de la Sonsierra in Rioja. He began to experiment with small-scale wine projects in the cave as he purchased more vineyard land, and meanwhile outfitted his parents’ garage with equipment to increase his capacity.

And then came his dream winery: “Between 2004 and 2006, I worked with architect Hector Herrera on the design,” says Benjamin. “It was built over the following two years and opened in June, 2008 to coincide with the summer solstice.

Benjamin Romeo, Bodega Contador

It is a nature-centered endeavor with terraces covered with plants that blend in with the local vegetation. The winemaker adds, “The bodega has exposed concrete walls so that gradually they become coated with dust and end up melding with the earth from which they came.”

Benjamín Romeo currently owns 124 acres of vineyards spread across 60 different plots, most of which are bush vines. He works with organic compost and shreds vine shoots over the soil to increase moisture retention. Selection, both on the vineyard and the winery, is essential to Romeo’s way of operating: He uses 10,000-litre wooden vats; malolactic fermentation is mostly done in barrels; aging times for red wines range from 16 to 18 months and he takes moon cycles into account when it comes to handling wines.

Both the 2004 and 2005 vintages of Contador received 100-point scores on Robert Parker’s Review—an unprecedented achievement for a Spanish winery. In fact, it’s a feat so tough that only a caveman could do it.

Bodega Contador ‘Alma Contador’, 2022 Rioja Alta ‘San Vicente de la Sonsierra’ ($123)

Bodega Contador ‘Alma Contador’, 2022 Rioja Alta ‘San Vicente de la Sonsierra’ ($123)

Romeo’s new red blend, 2020 Alma Contador, originates in three vineyards in San Vicente de la Sonsierra, each at different altitudes. It blends 92% Tempranillo with 8% Garnacha, which then matures in new French barriques for 20 months. The ‘soul’ of Contador is meant to showcases the power and elegance of Tempranillo with notes of black fruit, spice and vanilla. It is still quite young, but displays a structured palate with firm tannins and a long, lingering finish.

Rioja’s White Wine Revolution

Alavesa White, Orange and the Jurassic

In the mind of most wine drinkers, the most freely-associated Rioja color is red, and many are surprised to find out that the region has traditionally produced a sizeable amount of white wine—in days of yore, when the climate was cooler, Rioja had more white vineyards than red ones. In fact, it was not until the arrival of phylloxera in Bordeaux in 1866 (when merchants went looking for an alternative source of red wine) that red Rioja came into its own. And even then, these grapes were frequently used to make rosés or lighter reds called Ojo de Gallo by blending them with co-planted white varieties.

What’s true is that the white face of Rioja has suffered slings and arrows in the intervening years, many from critics who considered the offerings to be thin, overly-oaked, low on acidity and aromatics and frequently oxidized. In the middle of the twentieth century, white wine varieties still outnumbered reds in overall acreage, but it dwindled precipitously until it dipped below 10%. By the turn of the 21st century, Mercedes López de Heredia—who still crafts some of the country’s greatest and most traditional whites at her family’s bodega in Haro, admitted that she was starting to feel like ‘the last of the Mohicans.

The recent resurgence of Rioja white has been a deft balancing act between a past focused on aging in oak (and the dominance of Viura) and new grape varieties along with less traditional winemaking techniques. These are challenges that the next generation embraces, and are planting at higher altitudes with more focus on freshness and terroir.

Rioja’s three historic grape varieties—Garnacha Blanca, Malvasía de Rioja, and Viura—were all authorized when the Consejo Regulador was founded in 1925. The palette of varieties they can now choose from includes Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Maturana Blanca, the local grape Turruntés; also, fruit from old, overlooked vines in abandoned vineyards, with discoveries made of Calagraño, Jaén Blanco, Mazuelo Blanco, Moscatel de Alejandría, Palomino, Pavés, Rojal, and Xarel·lo. Better yet, old-vine Viura has overcome its poor reputation, at least in the best sites, and the development of new white-wine vineyards in areas that, in the days when the climate was substantially cooler, were considered marginal, has raised the bar on Rioja whites exponentially.

Naranja, brisé or amber: Call it what you will. In the absence of a name consensus the trend is clear, and Orange Wine has become a category in Rioja. Although its color makes it look like a rosé, orange wine is in fact the opposite: Rather than using red wine grapes, orange wines rely entirely on white varieties allowed to macerate until the must reaches the desired color and body. Like natural wine, orange wine is not to everyone’s taste, but Rioja’s top entries to the field display notes of dried figs, roasted apples, roasted almonds and fennel with hints of mango and citrus notes.

Another extraordinary style that Rioja is exploring is akin to the Jura’s vin jaune, traditional Sherry and aged White Burgundy where white wine undergoes extended aging to develop rich, nutty, oxidative characteristics.

Artuke ‘Trascuevas’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa White ($53)

Artuke ‘Trascuevas’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa White ($53)

90% Viura, 5% Malvasía, 5% Palomino Fino grown on calcareous clay soils from three different vineyards with vines over 50 years old. The harvest is done manually, and the grapes are transported in 20-kilogram boxes to the winery where they are destemmed, and pressed to initiate fermentation in stainless steel tanks with native yeasts. Afterward, the majority ages for 10 months in 500-liter French oak barrels, with a small percentage in concrete tanks. The wine shows a yeasty nose and a full palate of citrus, apple and pear.

Olivier Rivière ‘La Bastid’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa ‘Labastida’ White ($36)

Olivier Rivière ‘La Bastid’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa ‘Labastida’ White ($36)

85% Viura, 8% Garnacha Blanca, 7% Malvasía from Olivier’s Labastida vineyard planted on clay-lime soil. After careful sorting and pressing, the wine ages for ten months in 500-liter French oak barrels. It shows carefully crafted nuances of orange peel, anise seed, pear, nectarine and creamy vanilla.

Álvaro Loza Viticultor ‘Con.tacto’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa ‘Labastida’ Orange ($39)

Álvaro Loza Viticultor ‘Con.tacto’, 2022 Rioja Alavesa ‘Labastida’ Orange ($39)

100% Viura, known elsewhere as Macabeo, grown in a single ten-acre, south-facing plot in Elciego. The vineyard is mostly planted to Tempranillo, but Viura occupies the higher elevated end of the vine rows. The fruit is hand-harvested and whole-cluster fermented for 15 days in contact with the skins and the stems (hence, the name), then racked into 8 year old French oak barrels for one year. As in Sherry, the layer of ‘flor’ that forms in these barrels is yeast that allows fermentation to continue without oxidation. The label is a tribute to his grandfather, with his hand and Álvaro’s hand on the label, reminiscent of Michelangelo’s ‘Creation of Adam’ fresco in the Sistine Chapel.

Olivier Rivière ‘Mirando al Sur’, 2020 Rioja Alavesa ‘Labastida’ White ($98)

Olivier Rivière ‘Mirando al Sur’, 2020 Rioja Alavesa ‘Labastida’ White ($98)

100% Viura from 55-year-old vines planted near the village of Labastida in Rioja Alavesa. It is named Miranda al Sur (‘looking south’) not because of the vineyard’s exposure, but because it is aged in used Sherry butts (one Fino and one Amontillado) after a whole cluster fermentation in oak vats. The wine is richly toned with notes of Balsam wood and tangerine and a subtle herbal and mineral-spicy accompaniment. In the mouth it is broad and creamy, with layered viscosity; seamless and rounded.

- - -

Posted on 2025.04.07 in Spain DO, Wine-Aid Packages, Rioja DOC | Read more...

The Methodical Purist: Emmanuel Lassaigne (Champagne Jacques Lassaigne) is Redefining Terroir in Champagne’s Outlying Sub-region Montgueux + Southern Champagne Tapestry: Vincent Couche in Villages Montgueux and Buxeuil

The Methodists were named for a methodical approach to Christianity and the Puritans for a desire to purify it. Although Montgueux’s roots are a bit more pagan (the name means Hill of the Goths), Emmanuel Lassaigne’s angle of approach combines both philosophies, and in doing so, creates the region’s finest Champagne.

As an officially-delineated growing region, Montgueux—a mere fifteen minutes from Troyes—arrived late to the Champagne party; most of the current vines were planted in the 1960s. Among the first to reclaim Montgueux’s once-renowned terroir was Emmanuel Lassaigne’s father Jacques, from whom he took over Champagne Jacques Lassaigne in 1999.

As background notes to his latest project, a renowned two-acre Montgueux vineyard called Clos Saint-Sophie, Emmanuel says: “There were twenty varieties of grapes growing here in the 1880s. The Clos was so well known that Japanese botanists came to study it in 1886 and took a hundred cuttings back with them—the first Vinifera vines to grow in Japan.”

Join us on an exploration of this tiny chalk hill 60 miles south of Épernay, unlike anywhere else in Champagne, led by the tour guide who knows it best, Emmanuel Lassaigne. So in love with Montgueux is Lassaigne that he purchases up to 30% of his grapes from vineyards he does not own simply to present a more unified spectrum of the region’s remarkable terroir.

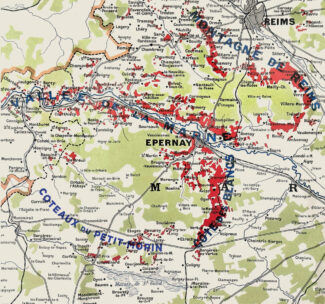

The Landscape of Champagne: Rethinking the Sub-regions

Classification is a man-made phenomenon; a way of understanding and categorizing a complicated world. Biologists do it, chemists do it, musicologists do it, but no field of study seems more joined at the hip to classification than oenology. Champagne, for example, has typically been subdivided into three major regions—the Montagne de Reims, the Côte des Blancs and the Vallée de la Marne. But, like the platypus who threw a curve ball to biologists as an egg-laying, duck-billed mammal, the classical subdivisions of Champagne ignore a portion of the 84,000 acres legally allowed to wear the Champagne label.

On the other end of the scale, the Comité Champagne (an umbrella organization for both growers and Champagne Houses first formed in 1898 to combat phylloxera) offers its own dizzying classification system, dividing the region in twenty individual sub-regions.

Finding neither taxonomy satisfactory, Champagne writer and former editor of ‘Wine & Spirits’ Peter Liem has found a middle, yet all-inclusive ground with seven named sub-regions—even while admitting that he is courting controversy.

Of the original three divisions, he leaves the Montagne de Reims and the Côte des Blancs intact, but argues that Vallée de la Marne should be broken in two to reflect the chalky bedrock of the northeast supporting primarily Pinot Noir and the collection of villages southwest of Épernay (called, unsurprisingly, the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay) where, within a relatively small region, a distinct variety of soils and terroirs can be found. The Côte des Bar is handed to us ‘as is’ since the principal vineyard area of the Aube lies on Kimmeridgian marl, much like its neighbor Chablis.

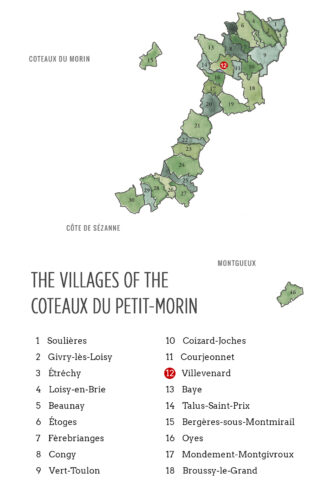

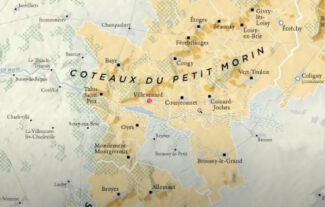

The most interesting sub-category in Liem’s system is the quartet of Côte de Sézanne, Coteaux du Morin, Vitryat and Montgueux. He groups them together despite their unique but isolated characteristics chiefly because they are areas of new plantings.

• The 1500-acre Côte de Sézanne sits a few miles southeast of Étoge in the Côte des Blancs. Chardonnay accounts for around 75% of the vineyard plantings, but there is a significant amount of Meunier and Pinot Noir. Sézanne wines are known for being among the fruit-forward in the region.

• Contiguous to the vineyards of Sézanne, the Coteaux de Morin forms the northern end of a string of vine-clad hills south of the Côte des Blancs. 2200 acres of vineyard comprise the region; about half is Meunier, 40% Chardonnay and the rest Pinot Noir.

• Vitryat is located in the Côte des Blancs but removed from the main by 25 miles (to the east); this is Chardonnay country, and this variety dominates Vitryat’s 1130 acres of limestone marl to produce elegant wines with a stony minerality unlike the crisper Champagnes that typifies the Côte des Blancs.

• Montgueux, the smallest of the four sub-regions, is made up of 514 acres of chalk, where the vines generally face south along a single hillside. These wines are renowned for their exotic fruit flavors, especially pineapple and mango. According to Emmanuel Lassaigne, “Our south-facing exposure always produces these tropical wines, but the soils are very chalky, so there is a lot of minerality too.”

Chalking Up Differences: Montgueux Rocks

In general, if you chalk up Champagne terroir to chalk, you are close, but like the grapes themselves, there are many flavors of this white, soft porous rock, made from the gradual accumulation of fossilized shells from marine life. The ‘Paris Basin’ is the key geological formation that produces the remarkable terroirs of northern France; a giant limestone bowl that, 75 million years ago, was a shallow sea where eukaryotic organisms lived, died and piled up. A slow tilting of this basin allowed the Seine, Aube, Yonne, and Loire rivers to cut through the rising ridges and form an archipelago of wine areas of which Champagne figures prominently, along with the Loire Valley and Burgundy.

The Campanian chalk that dominates the Côte des Blancs and the Côte de Sézanne is the standard-bearer for Champagne’s terroir, but the chalk in Montgueux and Vitryat, for example, is 13 million years older—deposits from the Turonian Stage.

Montgueux is an outcropping of pure Turonian chalk sitting three hundred feet above the surrounding plains, and although this soft limestone is the predominant mineral presence, small amounts of red clay and flint are also found in the soil—trace elements that allow Montgueux Chardonnay to express a full aromatic palate.

New Plantings: Reviving Historic Terroir in Coteaux du Morin, Côte de Sézanne, Vitryat, and Montgueux

The story of European wine is distinctly bifurcated: Before phylloxera and afterward. Prior to the Great Blight of the eighteenth century, more than 150,000 acres of Champagne were planted to vine. Today, that number is fewer than 90,000 acres. Root-devouring aphids alone did not account for the decline, of course; a couple of World Wars and the subsequent economic implosion played their role. Whatever the cause, in the process, some historically important terroirs were abandoned.

By the 1960’s, a renaissance had begun to find footing among growers, and Champagne vineland that had lain fallow for half a century was slowly replanted. Nowhere was this more in evidence than in Peter Liem’s Big Four—Coteaux du Morin, Côte de Sézanne, Vitryat and Montgueux, which have re-established themselves as important Champagne growing areas. Although there are fewer grower-producers today than in the past (with more growers selling grapes to major Champagne Houses and cooperatives) this leaves a vast opening for pioneers to learn about the varied faces of these long-untapped soils, climates and exposures.

Champagne Jacques Lassaigne

Wine First

If a poster child was needed for the concept of Champagne’s phoenix rising from the flames of phylloxera, no hill is better suited than Montgueux. And in the endeavor, no white knight may be considered more noble than Jacques Lassaigne. With the original intention of selling grapes to négociant houses, he began to bottle still wine in the 1970’s and Champagne in the ‘80s. His first ‘parcellaire’—a term synonymous with ‘lieu-dit’—was from Le Cotet, a plot that Emmanuel still farms today.

Of it, Emmanuel says, “We have a single area of vines between 55 and 60-years old within this individual vineyard, all Chardonnay, making a wine of intense minerality. It sings with citrus acidity in its youth but as it ages, it fattens. It’s another Champagne which must be treated as a white wine with bubbles, serving it (preferably) not too cold in the correct wine glass.”

Emmanuel Lassaigne, Champagne Jacques Lassaigne

From the outset, the Lassaignes relied on organic agriculture, using no synthetics and allowing the rows to grass over, creating competition with the vines—a technique that reduces yields and produces smaller berries, both indispensable factors in creating great wines. But as a Champagne house, they are decidedly not certified organic, for reasons that betray a small secret among French vignerons worth squirreling away: According to Emmanuel, “The French are masters in the art of paper. Many growers (like us) who work without chemicals prefer to remain uncertified because we resent having to deal with the bureaucracy and pay the fees to be certified in something we’ve been doing for years of our own accord.”

The majority of Lassaigne’s current ten acres is planted to Chardonnay, and lie across the street from his home above the valley that lies between Montgueux and Troyes. As mentioned, he annually purchases an additional six acres of grapes from old vines in top terroirs.

Of Clos Sainte-Sophie he says, “It’s the best vineyard in Montgueux.”

Emmanuel Lassaigne, courtesy of Grand Champagne Helsinki

In the cellar, Lassaigne vinifies all parcels separately and (with the exception of ‘Le Cotet’ and ‘Colline Inspirée’) fermentation is done in stainless steel. The initial fermentations are completed with native yeasts while secondary fermentations rely on a commercial, neutral Aube-originated yeast strain that imparts no aroma to the wine and promotes a very long, cool second fermentation—key to developing the prized mousse of which Champagne is justifiably proud. Although Lassaigne uses sulfur minimally at pressing to prevent oxidation, the domain has been disgorging without sulfur for 32 years. He scoffs at oenologists who insist that sulfur is a preventative measure, saying, “We’ve avoided it for more than a quarter century and to date, nothing has gone wrong.”

Emmanuel also disgorges all the bottles himself, by hand, which is an increasingly uncommon practice in Champagne where machine disgorgement has become the norm.

The human touch plays an integral role in every facet of winemaking with which Emmanuel engages. And it’s fitting, since Champagne is one of humanity’s greatest triumphs.

Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Les Vignes de Montgueux’, Montgueux Blanc-de-Blancs Extra-Brut ($79)

Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Les Vignes de Montgueux’, Montgueux Blanc-de-Blancs Extra-Brut ($79)

True to its name, the grapes in ‘Les Vignes de Montgueux’ come from seven to nine individual sites throughout Montgueux where the age of vines is around 35 years and yields are kept to 60 hectoliter/hectare (Champagne’s average is 66 hl/ha). Harvest is done at maximum ripeness before the grapes are destemmed and pressed. The base wine undergoes complete malolactic fermentation and is aged in new and old barrels for 12 to 24 months. Once bottled, it is held for one to five years until it is disgorged, corked and released.

The wine shows glints of gold in the glass with lovely dried mango and lemon-lime zest in the aromatics. The palate is vibrantly alive with crisp citrus and creamy melon flavors that are backed by a spine of acidity and dazzling minerality. The finish resonates with succulent pineapple and citrus notes and shows the full, expressive panoply of Chardonnay.

2015 Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Millésime’, Montgueux Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($169)

2015 Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Millésime’, Montgueux Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($169)

2015 vintage: After a wet winter and a mild spring, high temperatures and dry weather prevailed from mid-May until mid-August and the drought conditions produced wines with great concentration if a somewhat rustic tinge.

A blend of three parcels, 80% fermented in stainless steel and 20% in 225-liter foudres for eight months, then on lees for an additional eight years. Disgorged February, 2024 and dosed ‘brut nature,’ meaning less than 3 grams of sugar per liter.

Shows bright lemon, sour apple and pear notes with a touch of creaminess to warm it the shivery acidity and salinity.

Montgueux in Details: Story Told in Parcels

Emmanuel Lassaigne currently farms nearly nine acres of vines, but he also purchases grapes from another six acres so that his wines can represent all facets of Montgueux’s terroir. He then vinifies each parcel on indigenous yeast in order to preserve their individuality, either in barrel or in stainless steel.

“This allows me a wide palette for blending,” he explains, “even though the final wine is pure Montgueux. My vintage Champagne combines three parcels. The fifty year old vines in Les Grandes Côtes, for example, yield rich, buttery wines. I control the amount I use, but it offers depth and vinosity. Les Paluets makes wines that are sleeker and more elegant. I also have vines in Le Cotet that were planted in 1964. It is very citrussy, contributing freshness to the blend. Each parcel has its own story to tell, and I act as a editor that combines each story into a cohesive collection.”

2017 Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Le Grain de Beauté’, Montgueux ‘Le Cotet/Les Paluets’ Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($219)

2017 Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Le Grain de Beauté’, Montgueux ‘Le Cotet/Les Paluets’ Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($219)

2017 Vintage: In Champagne, 2017 got off to a promising start with warm, dry conditions through late spring and early summer, hurrying along budburst and flowering. August was universally rainy, though, prompting an outbreak of botrytis. This meant that the harvest had to be carried out quickly and for some producers, it was the shortest on record. Chardonnay tended to be uniformly good and there was also some extremely good Pinot Noir, with Meunier suffering from over-ripeness. Despite these setbacks, the potential for some great Champagnes exists.

From two parcels—Le Cotet and Les Paluets—the grapes were harvested by hand, destemmed, and gently pressed. The wine undergoes complete malolactic fermentation and is aged in barrels for 4 years until it’s bottled. Disgorged á la volée (manually). The wine shows a lovely minerality with dried fruit, citrus zest and melon on the nose.

2018 Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Autour de Minuit’, Montgueux ‘La Voie Creuse’ Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($283)

2018 Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Autour de Minuit’, Montgueux ‘La Voie Creuse’ Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($283)

2018 Vintage: An all-around excellent growing season preceded by an extremely wet winter which—albeit by chance—created a brimming water table for the long, hot summer that ensued. Despite some hail storms, the resulting crop was large and abundant; the grapes were mostly picked by hand and continuing good weather meant the harvest could be done at a leisurely pace, with all varieties performing well.

For this cuvée, Lassaigne collects barrels from Jean-François Ganevat formerly used in vin jaune production. The wine spends three years on it lees and is bottled without dosage. The exception balance of purity and tension shows through layers of creamy peach and lemon meringue.

A Jewel Reclaimed: The Montrachet of Champagne

“Explosively aromatic with notes of lemon peel, pomelo and passion fruit giving way to notes of gingerbread and toast.”

This could easily be mistaken for Montrachet tasting notes, but in fact, it is a description of Champagne from Clos Sainte-Sophie in Montgueux. Sainte-Sophie has a more easterly exposure than many local vineyards, giving the wines a unique structure and remarkable complexity. Under the ownership of the Valton family for the past hundred years, for much of this time, Sainte-Sophie fruit was sold to Charles Heidsieck for premium blends. Today, more and more is being dedicated to single-vineyards wines, especially those of Emmanuel Lassaigne.

Former Charles Heidsieck cellar-master Daniel Thibault confirms the original assessment, saying, “If there is a Montrachet in the Aube, it will be found in Montgueux.”

Montgueux—the ‘hill of the Goths’—is a fairly new region in Champagne, a chalky outcropping that is nearly all planted to Chardonnay, with only about 10% of the vineyard land given over to other varieties. Emmanuel Lassaigne, considered by many to be the finest winemaker in Montgueux, further illuminates the Montrachet-ness of the wines he produces: “Our south-facing exposure always produces rich wines with very ripe flavors; the soil is chalks, so there is always an undercurrent of minerality and notes of mango and tropical fruit.”

2017 Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Clos Sainte-Sophie’, Montgueux’ Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($237)

2017 Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Clos Sainte-Sophie’, Montgueux’ Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($237)

Clos Sainte-Sophie is a unique clos, the only one of the Champagne’s 13 walled vineyards situated in the Aube. Owned by the family behind French undergarment brand Le Petit Bateau, cuttings from the vineyard were used to plant the first wine grapes in Japan in 1877.

Lassaigne reached an agreement with the elderly owner to purchase Sainte-Sophie grapes in 2010. He vinifies the juice for six months in a combination of barrels previously used for Cognac, Savagnin ouillé and Burgundy. The juice is then blended in tank for 2 months and bottled in the spring of the following vintage before spending six years on the lees in bottle. It shows bright beams of acidity balanced by caramel cream and lemon/lime acidity.

2016 Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Clos Sainte-Sophie’, Montgueux Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($237)

2016 Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Clos Sainte-Sophie’, Montgueux Blanc-de-Blancs Brut-Nature ($237)

2016 Vintage: 2016 was tricky, with merciless April frosts devastating yields and in some cases wiping out entire crops. The weather continued to frustrate growers with heavy rains from May through to July, encouraging mildew and rot to further reduce yields. Warm, dry weather finally arrived in July and temperatures continued to creep up, with August reaching blistering highs that caused some grapes to suffer from burns. The harvest was down by roughly a third and smaller, more flexible producers like Emmanuel Lassaigne generally fared better than larger, more regimented houses.

The wine is 100% Chardonnay, disgorged March 2022, and bottled with zero dosage. It expresses Lassaigne’s characteristic intense aromatics and chalky notes along with pronounced acidity, a touch of meadow flowers, brioche and fleur de sel.

Southern Champagne Tapestry

Blending Villages Montgueux (Aube) and Buxeuil (Côte-des-Bar)

‘Aube’ translates to ‘dawn’, so it is fitting that this district is Champagne’s rising star. In part this is because of the district’s push towards a culture of artisanal, experimental, terroir-driven Champagne. Situated further south than the other four regions, it is less prone to frost and the Pinot Noirs of the Aube are rich and fruit-driven. Although the district is devoid of Grand or Premier Cru vineyards, since the 1950s, grapes grown there have formed a vital backbone of the blend produced by many of the top Champagne houses.

Perhaps the lack of a historical reputation means that the AOP has less to lose, but the overall mindset of the region encourages mavericks, which in tradition-heavy Champagne is rarely seen. It is these independent winemakers that are primarily responsible for district’s mushrooming growth, which now makes up almost a quarter of the entire Champagne region.

Since the Côte des Bars is the Aube’s only significant wine producing area, the two names are generally interchangeable in winemaking discussions; the vines of the Côte des Bar can be found scattered patches within two main districts, the Barséquenais, centered on Bar-sur-Seine, and the Barsuraubois, centered on Bar-sur-Aube.

Helping to forge the region’s new identity is a crew of younger grower/producers, many of whom have traveled abroad and trained in other winemaking regions. As a result, they tend to focus more on individuality; single-variety, single-vintage, and single-vineyard Champagnes from the Côte des Bar are quite common. Not only that, but land remains relatively inexpensive, which encourages experimentation. Even though many of Côte des Bar’s Champagnes are 100% Pinot Noir, styles can differ markedly from producer to producer, bottling to bottling and, of course, vintage to vintage.

Champagne Vincent Couche

The distance between Reims and Chablis is about two hundred miles and Vincent Couche’s approach to Champagne is more in line with traditional Burgundian thought and practices than many cellar masters: He farms small parcels kept separate with high-density plantings and focuses on wines of terroir rather than wines that are blended to a formula.

The fact that his properties are in the south of Champagne gives him a unique ability to explore the terroirs of this gently rolling terrain, where it is a touch warmer than the Marne, although it’s less centered on a major river system. He is enamored of ripeness, giving his cuvées their signature depth and complexity. In Chardonnay, extra hang-time (especially in a warmer growing season) produces luscious notes of nectarine and ripe pear while for Pinot Noir grapes the same conditions develop nuances of preserved cherry, fig and cocoa.

Aiming to Recreate Ideal Conditions for Harmonious Biodiversity and Precise Balance

Vincent Couche has been thinking about vines since he was eight years old. By early adulthood he was able to turn that fascination into a career, studying enology in Beaune and taking on several intern positions in Switzerland and Germany before founding his Champagne house in 1996. His current acreage of vines is split between two unique terroirs: Seven acres of Chardonnay in Montgueux and 25 acres of Pinot Noir in Buxeuil, where the parcels mostly face south and west on steep slopes overlooking the Seine.

Vincent Couche

“To succeed in winemaking, you must combine a respect for the land to an attachment to ancestral know-how, close to nature. You must excel as a craftsman who leaves no detail untouched, from the soils that produce the fruit vats and storage places, including the bottles. Everything is carefully chosen with the sole aim of obtaining high-end quality.”

His love of nature translated into a meeting with agricultural engineers in 1998 that prompted him to switch to organic and biodynamic cultivation in 1998. His estate was Demeter certified in 2011.

“Earth friendly winemaking as a philosophy is having a moment right now,” Vincent declares. “We pick grapes by taste and touch, and generally harvest over a week after our neighbors in both Montgueux. We are after higher levels of ripeness than is the norm.”

Couche is also a master at producing ratafia—a cordials made by the maceration of ingredients such as aromatic fruits and nuts in pre-distilled spirits, followed by filtration and sweetening.

Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Chardonnay de Montgueux’, Montgueux Brut-Nature ($75)

Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Chardonnay de Montgueux’, Montgueux Brut-Nature ($75)

2012 is used as the base year with a 2019 disgorgement and zero dosage; eight years on lees has produced a lovely baker’s aroma with yeast and dried green apple on the nose with lean tart lemon and a very fine mousse.

2014 Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Champagne de Buxeuil’, Côte-des-Bar ‘Buxeuil’ Extra-Brut ($99)

2014 Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Champagne de Buxeuil’, Côte-des-Bar ‘Buxeuil’ Extra-Brut ($99)

2014 Vintage: A warm, dry spring meant the growing season got off to a healthy start with successful budburst and flowering while the absence of severe frost gave producers cause for optimism. Summer dashed these original hopes with a rainy June and July and an August that did not dry out until midway through. Then a benign September brought warm, dry conditions ripening the grapes and effectively saving the harvest and the resulting crop, although not exceptional, was generally very good.

37% Chardonnay, 63% Pinot Noir. Disgorged in December 2021 and dosed at 4 gram/liter. The predominance of Pinot shows in dried cherry aromatics; the Chardonnay shines through with the beautiful chalky freshness with notes of warm pastry.

10,562 bottles and 912 magnum produced.

Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Élégance’, Montgueux+Buxeuil Extra-Brut ($56)

Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Élégance’, Montgueux+Buxeuil Extra-Brut ($56)

84% Pinot Noir and 16% Chardonnay, disgorged in February, 2022. The Pinot is grown in Buxeuil’s Kimmeridgian limestone and the Chardonnay in clay and silex from Montgueux. The wine spends three years on lees before disgorgement and dosed with zero sugar. It shows vibrant high-acid roundness with crunchy pear, raspberry, and golden delicious apple fruit and a kiss of brioche from the yeast.

5000 cases produced.

2002 Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Sensation’, Montgueux+Buxeuil Brut-Nature ($153)

2002 Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Sensation’, Montgueux+Buxeuil Brut-Nature ($153)

2002 Vintage: A sensational vintage! The preceding winter was cold and frosty and moved slowly towards a late spring. However, when it did arrive, spring was ideal, allowing for a successful flowering. Summer brought a succession of dry, sunny days that vintners dream about, ripening but not burning the grapes. Harvest was leisurely and the resulting wines were beautifully balanced and opulent with sharp acidity—ideal for cellar aging.

Half Pinot Noir and half Chardonnay, aged four months on lees and a full twenty years on lees in the bottle before disgorging in May, 2022. Dosed at zero. The wine shows hints of lime oil and orange blossom on the nose while the palate is full, complex with notes of pear and apple. The acidy remains alive and well despite the years in the bottle with enormous, mineral-driven length.

950 cases produced.

2000 Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Sensation – Dégorgement Tardif’, Montgueux+Buxeuil Extra-Brut ($368) 1.5 Liter

2000 Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Sensation – Dégorgement Tardif’, Montgueux+Buxeuil Extra-Brut ($368) 1.5 Liter

2000 Vintage: To kick off the 2000 growing season, spring was dry, but both June and July saw bouts of hail which caused considerable damage to certain vineyard plots. A warm August brought plenty of sunshine which lasted through to the September harvest. Overall, the wines were a touch low in acid but had good fruit, body and structure and some great wines were made.

‘Dégorgement Tardif’ is a Champagne term that signifies a late removal of dead yeast cells (lees) from the bottle, resulting in a wine with a richer, more complex character. 50% Pinot Noir and 50% Chardonnay, this beautifully aged Champagne was disgorged in May, 2021 and displays fine, well-integrated bubbles mingling with notes of dried stone fruit, Meyer lemon, honeyed apple, crushed chalk and toasted brioche.

450 cases produced.

Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Rosé Désir’ Montgueux+Buxeuil Brut-Nature Rosé ($62)

Champagne Vincent Couche ‘Rosé Désir’ Montgueux+Buxeuil Brut-Nature Rosé ($62)

95% Pinot Noir and 5% Chardonnay, this cuvée relies on blending three rosé style—carbonic, traditionally extracted, macerate fruit and some direct press. It spends a year in fût, three years on the lees before being disgorged and bottled unfiltered with zero dosage. The wine boasts a radiant nose of red berries against glimmers of spiced biscotti and roasted cashew. A silken palate of black cherry underlined by blood-orange rind before a long voluptuous finish.

600 cases produced.

- - -