Gamay Expressed in 8 Appellations by Beaujolais’ New Generation: A Wealth of Terroir (10-Bottle Pack $298, Tax Included)

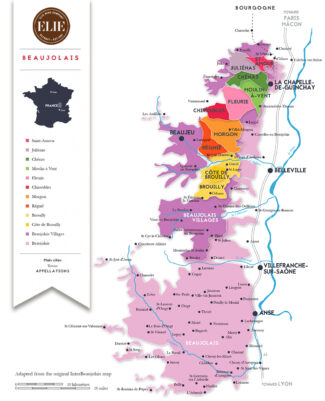

A few miles north of Lyon lies Beaujolais, a storied French wine appellation that overlaps both Burgundy and the Rhône, paying homage to both while owing allegiance to neither. The picturesque vineyards are planted almost exclusively to Gamay for reds and have been producing accessible, fruit-forward wines since the Romans first established trading routes along the Saône valley. Nearby Lyon is said to be ‘a city of three rivers’—the Rhône and Saône rivers that converge here, and then, the river of cool Beaujolais wine that drenches its food-centered heart. With 4300 restaurants (including twenty that boast Michelin stars), Lyon is host to such internationally renowned chefs as Paul Bocuse and Guy Lassausaie, and has rightly been nicknamed ‘The Gastronomic Capital of the World.’

Beaujolais is filled with rolling hills and bucolic villages, unique in France in that relatively inexpensive land has allowed a number of dynamic new wine producers to enter the business. In the flatter south, easy-drinking wines are generally made using technique known as carbonic maceration, an anaerobic form of closed-tank fermentation that imparts specific, recognizable flavors (notably, bubblegum and Concord grape). Often sold under the Beaujolais and Beaujolais-Villages appellations, such wines tend to be simple, high in acid and low in tannin, and are ideal for the local bistro fare. Beaujolais’ suppler wines generally come from the north, where the granite hills are filled with rich clay and limestone. These wines are age-worthy, and show much more complexity and depth. The top of Beaujolais’ classification pyramid is found in the north, especially in the appellations known as ‘Cru Beaujolais’: Brouilly, Chénas, Chiroubles, Côte de Brouilly, Fleurie, Juliénas, Morgon, Moulin-à-Vent, Regnié and Saint-Amour. Each are distinct wines with definable characteristics and individual histories; what they have in common beyond Beaujolais real estate is that they are the pinnacle of Gamay’s glory in the world of wine.

Beaujolais is filled with rolling hills and bucolic villages, unique in France in that relatively inexpensive land has allowed a number of dynamic new wine producers to enter the business. In the flatter south, easy-drinking wines are generally made using technique known as carbonic maceration, an anaerobic form of closed-tank fermentation that imparts specific, recognizable flavors (notably, bubblegum and Concord grape). Often sold under the Beaujolais and Beaujolais-Villages appellations, such wines tend to be simple, high in acid and low in tannin, and are ideal for the local bistro fare. Beaujolais’ suppler wines generally come from the north, where the granite hills are filled with rich clay and limestone. These wines are age-worthy, and show much more complexity and depth. The top of Beaujolais’ classification pyramid is found in the north, especially in the appellations known as ‘Cru Beaujolais’: Brouilly, Chénas, Chiroubles, Côte de Brouilly, Fleurie, Juliénas, Morgon, Moulin-à-Vent, Regnié and Saint-Amour. Each are distinct wines with definable characteristics and individual histories; what they have in common beyond Beaujolais real estate is that they are the pinnacle of Gamay’s glory in the world of wine.

Moulin-à-Vent

At the top of Beaujolais, geographically and arguably, in terms of quality, Moulin-à-Vent’s oddly toxic soils produce wines of great merit. Manganese exists here in quantities not found anywhere else in Beaujolais; it retards leaf growth and creates smaller bunches, resulting in wines of phenomenal concentration that can be cellared for a decade or more.

In the 18th century Château du Moulin-à-Vent was called Château des Thorins, named for the renowned vines on the hillsides of Thorins—a Mâconnais proverb runs, “Every wine is good with a meal, but a meal cannot be enjoyed without Thorins.” The estate was purchased in 2009 by the Parinet family, who has made a marvelous effort to extract the most from the chemical-rich terroir—the underlying granite soil contains iron oxide, copper and, of course, manganese. Château du Moulin-à-Vent, Moulin-à-Vent – Le Moulin-à-Vent 2018, ($40), comes from an exceptional vintage and is one of the château’s signature wines, sumptuous and expressive. It shows juicy black fruits, lavender and a myriad spices from the partial oak-aging.

In the 18th century Château du Moulin-à-Vent was called Château des Thorins, named for the renowned vines on the hillsides of Thorins—a Mâconnais proverb runs, “Every wine is good with a meal, but a meal cannot be enjoyed without Thorins.” The estate was purchased in 2009 by the Parinet family, who has made a marvelous effort to extract the most from the chemical-rich terroir—the underlying granite soil contains iron oxide, copper and, of course, manganese. Château du Moulin-à-Vent, Moulin-à-Vent – Le Moulin-à-Vent 2018, ($40), comes from an exceptional vintage and is one of the château’s signature wines, sumptuous and expressive. It shows juicy black fruits, lavender and a myriad spices from the partial oak-aging.

Chiroubles

Chiroubles is relatively tiny, with fewer than a thousand acres under vine, but it is a mouse that roars. This is due mostly to elevation; Chiroubles vineyards are the highest in Beaujolais, with some planted 1500 feet above the Saône River valley. Taking advantage of extreme diurnal shifts between the warm days and cold nights, the same soils that produce Fleurie to its immediate north here build wines that are lighter and fresher, often with pronounced floral characteristics.

Daniel Bouland is an artisan in the style of old-school winemakers. He works his vines by hand, and many are grown in small plots known as lieu-dits—portions of a vineyard with specific topographic or historical significance. Better known for his Morgons, Daniel Bouland ‘Cuve No 11’, Chiroubles-Chatenay 2019, ($36), hails from such a lieu-dit (Chatenay) in the neighboring appellation of Chiroubles, on a steep hillside site composed of friable sandstone. Such terroir produces beautiful, fragrant, sappy Gamay wines with the structure of many Burgundies. It has a nose of violets and thyme, a rich mid-palate of cherry and cranberry underscored by orange peel, Damson plum and crisp minerality.

Daniel Bouland is an artisan in the style of old-school winemakers. He works his vines by hand, and many are grown in small plots known as lieu-dits—portions of a vineyard with specific topographic or historical significance. Better known for his Morgons, Daniel Bouland ‘Cuve No 11’, Chiroubles-Chatenay 2019, ($36), hails from such a lieu-dit (Chatenay) in the neighboring appellation of Chiroubles, on a steep hillside site composed of friable sandstone. Such terroir produces beautiful, fragrant, sappy Gamay wines with the structure of many Burgundies. It has a nose of violets and thyme, a rich mid-palate of cherry and cranberry underscored by orange peel, Damson plum and crisp minerality.

Côte de Brouilly

To suggest that Côte de Brouilly erupts with flavor is more than a metaphor; the appellation sits on the slope of an extinct volcano. Making up but a small fraction of the Brouilly appellation, Côte de Brouilly draws its unique terroir from volcanic blue diorite, which provides the thin, well-drained soil that causes vines to struggle and the resulting wine—concentrated and intense—to shine. The vineyards of Côte de Brouilly are found on the south and east slopes of Mont Brouilly, protected from winds from the nearby Beaujolais hills by the volcano itself. They enjoy morning sunlight maximized by the steep slopes of the vineyards. This hastens ripening so that the vineyards of Côte de Brouilly are among the first to be harvested in Beaujolais.

Domaine de la Voûte des Crozes, Côte de Brouilly 2019, ($23). So highly is La Voûte des Crozes winemaker Nicole Chanrion regarded in Côte-de-Brouilly that in 2000, she was elected president of the appellation. With oversight of all aspects of the process, from winter pruning, to managing the canopy, hand-harvesting and fermentation, she produces a wine whose tannins match ripeness of the fruit. Ample and layered with a succulent core of black-cherry, the acid remains front and center while a streak of minerality reflects the volcanic schist terroir.

Domaine de la Voûte des Crozes, Côte de Brouilly 2019, ($23). So highly is La Voûte des Crozes winemaker Nicole Chanrion regarded in Côte-de-Brouilly that in 2000, she was elected president of the appellation. With oversight of all aspects of the process, from winter pruning, to managing the canopy, hand-harvesting and fermentation, she produces a wine whose tannins match ripeness of the fruit. Ample and layered with a succulent core of black-cherry, the acid remains front and center while a streak of minerality reflects the volcanic schist terroir.

The artisan vigneron reappears in Côte de Brouilly with Daniel Bouland ‘Cuvée Mélanie Cuve No 1’, Côte de Brouilly 2019, ($36), a wine comparable in complexity, depth and cellaring potential to a Côte de Beaune. Another lieu-dit gem, this wine shows kirsch fragrances along with cassis, blackberry and smoke. Like all of Bouland’s wines, this one is made from hand-harvested grapes, vinified with full clusters and bottled unfiltered.

The artisan vigneron reappears in Côte de Brouilly with Daniel Bouland ‘Cuvée Mélanie Cuve No 1’, Côte de Brouilly 2019, ($36), a wine comparable in complexity, depth and cellaring potential to a Côte de Beaune. Another lieu-dit gem, this wine shows kirsch fragrances along with cassis, blackberry and smoke. Like all of Bouland’s wines, this one is made from hand-harvested grapes, vinified with full clusters and bottled unfiltered.

Saint-Amour

The wines of Saint-Amour are light and delicate, the result of dry, warm winds from the north that keeps soils feathery-textured; although Gamay is the predominant varietal, it’s no wonder that this appellation produces more white wines than the other Beaujolais cru, although these Chardonnay/Aligoté -based wines often wear generic labels or are listed under the Saint-Véran (Burgundy) appellation that slightly overlaps Saint-Amour.

Pierre-Marie Chermette was raised in the vineyard; his fondest memories of the family home in Vissoux was riding the tractor. He pursued it as his life’s work, earning a National Diploma of Oenologist from Dijon at the age of 20. Two years later, he convinced his father to stop selling the fruits of his labor to merchants, and developed the market for estate bottled wines. Over the years, Pierre-Marie diversified the number of appellations the family worked, and is now responsible for nearly 75 acres. For obvious reasons, Pierre-Marie Chermette, Saint-Amour-Les Champs Grilles 2018, ($30) is marketed for Valentine’s Day, for which it is perfectly suited: The nose is rose petals and cherry blossoms, and the palate is filled with lush red fruits and chocolate layered across gentle tannins.

Pierre-Marie Chermette was raised in the vineyard; his fondest memories of the family home in Vissoux was riding the tractor. He pursued it as his life’s work, earning a National Diploma of Oenologist from Dijon at the age of 20. Two years later, he convinced his father to stop selling the fruits of his labor to merchants, and developed the market for estate bottled wines. Over the years, Pierre-Marie diversified the number of appellations the family worked, and is now responsible for nearly 75 acres. For obvious reasons, Pierre-Marie Chermette, Saint-Amour-Les Champs Grilles 2018, ($30) is marketed for Valentine’s Day, for which it is perfectly suited: The nose is rose petals and cherry blossoms, and the palate is filled with lush red fruits and chocolate layered across gentle tannins.

Morgon

Morgon, on the western side of the Saône, may only appear on the label of a Gamay-based red wine; even so, the appellation allows the addition of up to 15% white wine grapes: Chardonnay, Aligoté or Melon de Bourgogne. Nevertheless, the wines of Morgon wind up being among the most full-bodied in Beaujolais, with the potential to improve in the cellar so consistently that the French describe wines from other AOPs that display this quality by saying, “It Morgons…” The vineyards occupy slightly under five square miles surrounding the commune of Villié-Morgon, with the vines of Fleurie and Chiroubles directly to the north and Brouilly and Regnié along the southern border.

Marie-Élodie Zighera-Confuron is the proprietor of Clos de Mez, and maintains the vineyards’ matriarchal lineage. She explains, “Vines have been in my maternal family for four generations. The grapes they grew were delivered to the cooperative cellar by my grandmother and mother, up until I arrived at the domain as a winegrower. However, this did not deter my grandmother or mother from taking great care of the vineyard.” Clos de Mez, Morgon-Château Gaillard 2012, ($22)is not to be confused with Normandy’s Château Gaillard; here it is a lieu-dit in the northern part of Morgon bordering on Fleurie. The vines are all over 60 years old; they produce a distinctive, meaty wine that has been compared to a Rhône for its dark cherry profile enlivened by licorice, plum and a taut, mineral-tinged acidity.

Marie-Élodie Zighera-Confuron is the proprietor of Clos de Mez, and maintains the vineyards’ matriarchal lineage. She explains, “Vines have been in my maternal family for four generations. The grapes they grew were delivered to the cooperative cellar by my grandmother and mother, up until I arrived at the domain as a winegrower. However, this did not deter my grandmother or mother from taking great care of the vineyard.” Clos de Mez, Morgon-Château Gaillard 2012, ($22)is not to be confused with Normandy’s Château Gaillard; here it is a lieu-dit in the northern part of Morgon bordering on Fleurie. The vines are all over 60 years old; they produce a distinctive, meaty wine that has been compared to a Rhône for its dark cherry profile enlivened by licorice, plum and a taut, mineral-tinged acidity.

Fleurie

As mentioned, each of the Beaujolais crus wears its own pretty face; where Morgon is bold and handsome and Saint-Amour is a fairyland of delicate beauty, Fleurie—covering an unbroken area of three square miles—represents Beaujolais’ elegance. The terroir is built around pinkish granite that is unique to this part of Beaujolais, with the higher elevations accounting for thinner, acidic soils that produce graceful and aromatic wines. Below the main village, the wines are grown in deeper, richer, clay-heavy soils and the wines themselves are richer and deeper and appropriate for the cellar. The technique known as gridding, which involves extracting more color and tannin from the skins of the grapes, is proprietary to Fleurie.

Clos de Mez, Fleurie-La Dot 2012, ($22)sees the return of Marie-Élodie Zighera-Confuron to her native Fleurie, where La Dot refers to a plot of vines, now fifty years old, that her grandmother once received as a dowry. White flowers and cut grass waft through the nose and lead to a beautiful palate of pomegranate and raspberry; the wine finishes with granitic acidity and a dusting of baking spices.

Clos de Mez, Fleurie-La Dot 2012, ($22)sees the return of Marie-Élodie Zighera-Confuron to her native Fleurie, where La Dot refers to a plot of vines, now fifty years old, that her grandmother once received as a dowry. White flowers and cut grass waft through the nose and lead to a beautiful palate of pomegranate and raspberry; the wine finishes with granitic acidity and a dusting of baking spices.

Pierre-Marie Chermette, Fleurie-Poncié 2017 ($27) also reintroduces the tractor-fan turned enologist from Le Vissoux. Although the family estate is in Saint-Vérand, in the Golden Stone area of Rhône, the luscious Fleurie from the lieu-dit Poncié is a paean to the sandy slopes of pink granite north of the town itself. The wine is resplendent with sweet red cherries, dried flowers and ripe strawberries enveloped in silky tannins.

Pierre-Marie Chermette, Fleurie-Poncié 2017 ($27) also reintroduces the tractor-fan turned enologist from Le Vissoux. Although the family estate is in Saint-Vérand, in the Golden Stone area of Rhône, the luscious Fleurie from the lieu-dit Poncié is a paean to the sandy slopes of pink granite north of the town itself. The wine is resplendent with sweet red cherries, dried flowers and ripe strawberries enveloped in silky tannins.

Beaujolais-Villages

Of the three Beaujolais classifications, Villages occupies the middle spot in terms of quality. To qualify, the wine generally hails from more esteemed terroirs in the northern half of Beaujolais, from one of 38 villages that have not been named ‘cru’ appellations. They are expressive wines with more structure and complexity than generic Beaujolais, though not as exclusive as those from the ten crus. Accounting for about a quarter of all Beaujolais production, Villages wines are most often produced by négociants and vinified using stricter rules as to yields and technique.

Jean Foillard, Beaujolais-Villages 2019, ($27), is a solid example of the classification, brilliant red with a purplish tint, offering round, juicy mouth-filling strawberry and cherry flavors with spice in the background and a rustic, lightly tannic finish. A disciple of traditionalist Jules Chauvet, who eschewed the styles touted by commercial brands, Jean Foillard produces wines that are sumptuous and complex, with a velvety lushness that makes them irresistible in their youth.

Jean Foillard, Beaujolais-Villages 2019, ($27), is a solid example of the classification, brilliant red with a purplish tint, offering round, juicy mouth-filling strawberry and cherry flavors with spice in the background and a rustic, lightly tannic finish. A disciple of traditionalist Jules Chauvet, who eschewed the styles touted by commercial brands, Jean Foillard produces wines that are sumptuous and complex, with a velvety lushness that makes them irresistible in their youth.

Beaujolais

Brooding Beaujolais is an oxymoron; buoyant Beaujolais is a requirement. The broadest of all the classifications in Beaujolais, seeing such a designation on a wine label means that the grapes are generally grown in the southern part of the appellation and vinified using carbonic or semi-carbonic maceration, leaving dominant, candy-like notes. Beaujolais’ climate is similar to Burgundy—moderate continental—and the main difference in the output is that whereas Burgundy’s Pinot Noir is fickle and difficult to ripen, Beaujolais’ rock star Gamay is an early-budding, early-ripening and vigorous cultivar. As such, outputs (if not controlled) can be overly prodigious.

Pierre-Marie Chermette ‘Origine Vieilles Vignes’ Beaujolais 2018, ($18), falls under this generic appellation with the specification of ‘Origine Vieilles Vignes’, or ‘original old vines’. It is produced in Saint Vérand from vines that have grown on a dark granite enclave for up to a century. The cuvée was created in 1986 when banana-flavored Beaujolais Nouveau was in vogue; Pierre-Marie wanted to create a non-chaptalized spring-release Beaujolais using natural yeast and vinified by using traditional methods. It is bright and beautiful, suave and supple, and exhibiting great color and freshness.

Pierre-Marie Chermette ‘Origine Vieilles Vignes’ Beaujolais 2018, ($18), falls under this generic appellation with the specification of ‘Origine Vieilles Vignes’, or ‘original old vines’. It is produced in Saint Vérand from vines that have grown on a dark granite enclave for up to a century. The cuvée was created in 1986 when banana-flavored Beaujolais Nouveau was in vogue; Pierre-Marie wanted to create a non-chaptalized spring-release Beaujolais using natural yeast and vinified by using traditional methods. It is bright and beautiful, suave and supple, and exhibiting great color and freshness.

- - -

Posted on 2021.06.15 in France, Beaujolais, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

The Champagne Society June 2021 Selection: Champagne André Clouet

Champagne André Clouet ‘Dream Vintage 2008’ Grand Crus Ambonnay/Bouzy

Price for members of The Champagne Society: $83 (Regular $97)

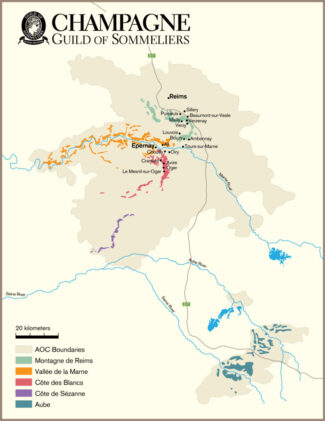

“Bouzy and Ambonnay are the epicenter of Pinot Noir in Champagne, and the Clouet family is the privileged custodian of eight hectares of estate vines in the best middle slopes of both villages. These are rich and concentrated expressions of Pinot Noir, wines of deep complexity, multifaceted interest and engaging character, yet with remarkable restraint and sense of control. Tasting after tasting confirm my impression that this small and relatively unknown grower ranks high among Champagne’s finest practitioners of Pinot Noir—and represents one of the best value of all.” Tyson Stelzer, The Champagne Guide 2016-2017: The Definitive Guide to Champagne.

Young Chef de cave Jean-François Clouet is deeply passionate about the remarkable sweep of history that has played out in this place over two millennia, and every time I visit he speaks more of this than he does of vines, winery, cellar or tastings. He shows me original documents of his village of Bouzy in his archive and takes me to another part of town to recount another branch of history: Attila the Hun, the Catalonic Field Battle, the birth of the monarchy, the crusades, the Templars, Marie Antoinette. ‘To understand Champagne you need to understand its political history,’ he says.

For Clouet’s family, that history began here in 1492, and his family still resides in the house his ancestors built in Bouzy in 1741. ‘My family was making wine in Champagne at the same time Dom Pérignon was starring!’ he exclaims. This history lives on, not only in the spectacular labels designed by Jean-François’ great grandfather in 1911 (harking back to the family’s printer heritage, making books for the kings since 1491), but in a traditional approach in the vineyards. ‘I like the idea of the work of human hands in pruning. Performing the same actions as my grandfather and even the Romans, who planted vines here 2000 years ago.’

The flamboyant Jean-François is one of the upcoming rockstars of Champagne. He is inherently talented as a winemaker, keenly insightful, at once deeply rooted in his family’s history and yet daringly creative, with a distinctly modern twist to his approach. It is his goal that some day none of his Champagnes will have any dosage at all, an ideal that he rightly describes as a revolutionary. ‘Not to be snobby or arrogant, but I have a real sense that a zero-dosage wine from a single village can really showcase the pedigree of the village,’ he suggests. ‘You have to be an extremely good winemaker to make zero-dosage champagne.’ And if anyone can do it anywhere, Jean-François can in Bouzy and Ambonnay.

The flamboyant Jean-François is one of the upcoming rockstars of Champagne. He is inherently talented as a winemaker, keenly insightful, at once deeply rooted in his family’s history and yet daringly creative, with a distinctly modern twist to his approach. It is his goal that some day none of his Champagnes will have any dosage at all, an ideal that he rightly describes as a revolutionary. ‘Not to be snobby or arrogant, but I have a real sense that a zero-dosage wine from a single village can really showcase the pedigree of the village,’ he suggests. ‘You have to be an extremely good winemaker to make zero-dosage champagne.’ And if anyone can do it anywhere, Jean-François can in Bouzy and Ambonnay.

To this end, for some years he has experimented with using Sauternes barriques from Château Doisy Daëne for alcoholic fermentation. ‘It gives the illusion of the wine being sweet, when it is not sweet at all!’ he claims. The result is quite magnificent. When Clouet began working on the estate 10 years ago, he took note of those embarking on organic and biodynamic regimes. ‘Biodynamics and organics look good on paper,’ he says, ‘but my idea is that it is simply important to take care of the ground by hand without the use of herbicides.’ Stringent sorting during harvest maintains freshness and purity in his cuvées.

Clouet’s focus remains resolutely on Pinot Noir, which comprises 100% of every cuvée except his Millésime, a 50/50 blend of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. ‘I am frustrated with the idea of blending from everywhere!’ he exclaims. ‘I love pure Pinot Noir! No make-up and no compromise!’ Clouet is fascinated by the geological history of his soils, and makes it his goal to express the minerality of pure chalk in his wines. ‘Fantastic minerality and low dosage are important for good Pinot Noir,’ he claims. His cuvées receive low dosage of 6g/L. In 2011 Clouet embarked on a significant project he dubs ‘Clouet world’, a substantial logistics facility for disgorgement, remuage and bottling on land he inherited just outside the village.

As seriously as he takes his responsibilities, Clouet doesn’t take himself too seriously. ‘Champagne is always for flirting!’ he grins. And likens his wines to independent films. ‘I love Hollywood movies, but sometimes I want to watch something independent. Winemaking in Champagne is the same,’ he says. ‘One is not better than the other. Dom Pérignon and Pol Roger are fantastic, with all the action of James Bond in Skyfall, but sometimes I have a taste of something else.’ His Champagnes offer that something else, without the Hollywood budget, yet with the pyrotechnics all of their own.

Champagne André Clouet ‘Dream Vintage 2008’

Champagne André Clouet ‘Dream Vintage 2008’

Grand Crus Ambonnay/Bouzy

“96 points. (A little more than 50% Chardonnay, the remainder Pinot Noir from Bouzy and Ambonnay; 6g/L dosage.)

“On its release two years ago, I adored this expression of exceptional vintage from this top grower, and its freeze-frame slow-motion evolution since has only exemplified its potential. Its impeccable, backward, primary focus on Bouzy’s red cherry and strawberry fruits is breathtaking, charged with the tension and precision of a back of electric 2008 acidity. Finesse and poise are framed in deep-set concentration, the signature of its villages, painted in the vivid colors of 2008. Subtle mixed spice complexity is beginning to peek out, but it remains very fresh and impeccably pure, carrying with unrelenting fruit depth, persistence and an ever-present undercurrent that froths with well-defined, finely chalky minerality. Wow.” Tyson Stelzer, The Champagne Guide 2016-2017: The Definitive Guide to Champagne.

- - -

Posted on 2021.06.10 in France, The Champagne Society, Champagne | Read more...

Pure Burgundy: Chardonnay Never Had It So Good. The Flagship Cuvées of Four of Chablis’ Top-Tier Producers (8-Bottle Pack $298, All Included)

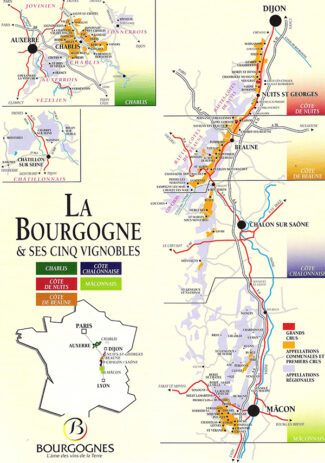

When Chardonnay is grown in climates less than ideal, resulting flaws are often tempered by oak. If such wines are described as cedary, buttery, vanilla-like or toasty, and chances are, the taster is defining qualities derived from the barrels used to ferment or mature the wine, because these are not qualities of the grape itself. Mineral notes like chalk, slate, schist or even powdered silica are the domain of the fruit; they are Chardonnay flavors, most of derived from the soil in which the grape vine grows.

Chablis—Burgundy’s most northerly appellation—produces the world’s most bracing and refreshingly uncluttered incarnation of Chardonnay. In Chablis, traditions are born of an ego that is mostly justified, and winemakers insist that the expression of the fruit be pure. That is not to say that no Chablis sees oak; many certainly do. It’s just that the whole approach to what barreling is supposed to accomplish in a glass is viewed differently in this rocky, chilly, outpost, less than a hundred miles from that other bastion of varietal purity, Sancerre.

Chablis is subdivided into four AOPs based on quality factors which nearly all come down to soil and slope and grape yields. The largest of these, simply called Chablis, covers about sixteen thousand acres; the smallest, designated Grand Cru, is only a couple hundred acres in size and is limited to seven vineyards. To Chardonnay fans, these are like the seven celestial Pleiades in Greek mythology; their name on a Chablis bottle is tantamount to magic and an expectation thereof. The Premier Cru designation can be affixed to any of seventeen vineyards on both sides of the River Serein; the best occupy the right bank near the Grand Crus; the rest are southwest of the city of Chablis.

Chablis is subdivided into four AOPs based on quality factors which nearly all come down to soil and slope and grape yields. The largest of these, simply called Chablis, covers about sixteen thousand acres; the smallest, designated Grand Cru, is only a couple hundred acres in size and is limited to seven vineyards. To Chardonnay fans, these are like the seven celestial Pleiades in Greek mythology; their name on a Chablis bottle is tantamount to magic and an expectation thereof. The Premier Cru designation can be affixed to any of seventeen vineyards on both sides of the River Serein; the best occupy the right bank near the Grand Crus; the rest are southwest of the city of Chablis.

It remains testimony to Chablis’ ‘amour-propre’ that the district is willing to count on breeding, not masking, to show off its wares.

This package includes two bottles from each of Chablis top-tier producers. (8-Bottle Pack $298, All Included)

Domaine Billaud-Simon

Credit Napoléon’s loss at Waterloo for the establishment of Domaine Billaud-Simon; Charles Louis Noël Billaud returned home from the war to plant vines on the family holdings in Chablis. A century later, the estate expanded with the marriage of his descendent Jean Billaud to Renée Simon. Since 2014 owned by Erwan Faiveley, the 42-acre site produces wine from four Grand Cru vineyards, including single-acre plots in Les Clos and Les Preuses. The Domaine also owns four Premier Cru vineyards, including Montée de Tonnèrre, Mont-de-Milieu, Fourchaume and Vaillons. Chablis 2017 ‘Tête d’Or’ ($46) is sourced from 28-year-old vines from a parcel sitting at the foot of the Premier Cru Montée de Tonnerre in the heart of the Chablis appellation; the name means ‘Head of Gold’ and shows pure green-apple and bitter almond with an almost saline-like intensity. It’s a letter-perfect oyster wine, nicely nuanced with graphite, grapefruit and lemon.

Credit Napoléon’s loss at Waterloo for the establishment of Domaine Billaud-Simon; Charles Louis Noël Billaud returned home from the war to plant vines on the family holdings in Chablis. A century later, the estate expanded with the marriage of his descendent Jean Billaud to Renée Simon. Since 2014 owned by Erwan Faiveley, the 42-acre site produces wine from four Grand Cru vineyards, including single-acre plots in Les Clos and Les Preuses. The Domaine also owns four Premier Cru vineyards, including Montée de Tonnèrre, Mont-de-Milieu, Fourchaume and Vaillons. Chablis 2017 ‘Tête d’Or’ ($46) is sourced from 28-year-old vines from a parcel sitting at the foot of the Premier Cru Montée de Tonnerre in the heart of the Chablis appellation; the name means ‘Head of Gold’ and shows pure green-apple and bitter almond with an almost saline-like intensity. It’s a letter-perfect oyster wine, nicely nuanced with graphite, grapefruit and lemon.

Domaine Billaud-Simon

Domaine Laroche

Vines were first planted in the confines of what is today Laroche the same year that algebra was invented; in 2021, both mathematics and Laroche are still going strong. Today, Domaine Laroche is one of the largest landholders of Grand Cru vineyards in Chablis, with 222 acres spread across the entire region. Michel Laroche—whose name is held in the same reverence in Chablis as Michel Chapoutier’s is in northern Rhône or Olivier Humbrecht’s in Alsace—relies on one-man plots, meaning that a single person is wholly responsible for the care of each vineyard parcel, from the pruning, soil conditioning and control of yields to the sorting of the harvest. Chablis 2018 ‘Saint-Martin’ ($32) is named for the patron saint of Chablis, a Roman cavalry officer who became a monk and was elected Bishop of Tours. The cuvée is a blend of the best plots, all sit on Chablis’ legendary Kimmeridgian soil, and produce excellent acidity and remarkable finesse. The wine shows Bartlett pear and lily on the nose, pineapple and honey in the mid-palate and violet and candied lemon on the textured, creamy finish.

Vines were first planted in the confines of what is today Laroche the same year that algebra was invented; in 2021, both mathematics and Laroche are still going strong. Today, Domaine Laroche is one of the largest landholders of Grand Cru vineyards in Chablis, with 222 acres spread across the entire region. Michel Laroche—whose name is held in the same reverence in Chablis as Michel Chapoutier’s is in northern Rhône or Olivier Humbrecht’s in Alsace—relies on one-man plots, meaning that a single person is wholly responsible for the care of each vineyard parcel, from the pruning, soil conditioning and control of yields to the sorting of the harvest. Chablis 2018 ‘Saint-Martin’ ($32) is named for the patron saint of Chablis, a Roman cavalry officer who became a monk and was elected Bishop of Tours. The cuvée is a blend of the best plots, all sit on Chablis’ legendary Kimmeridgian soil, and produce excellent acidity and remarkable finesse. The wine shows Bartlett pear and lily on the nose, pineapple and honey in the mid-palate and violet and candied lemon on the textured, creamy finish.

Domaine Laroche

Christian Moreau Père & Fils

The pedigree of the Moreau name dates to 1814 when barrel-maker Jean-Joseph Moreau founded a wine-merchant trading firm in Chablis. Although that original firm has changed hands several times, including a sale to Hiram Walker in 1985 and again to the Boissets of Nuits-Saint-Georges in 1998, the Moreau family never relinquished control of their vineyards. Domaine Christian Moreau Père et Fils began vinifying at the turn of the 21st century, and is now under the watchful care of Fabien Moreau: “Being the 6th generation of the family producing wines, was and still is a challenge for me, trying to avoid the pressure you could have with this wine heritage. But with the quality of the vineyard that my family passed on, the basis of the expression of our wines is here, and our work is to honor our terroirs.” Chablis 2018 ($36) is a cuvée built from grapes purchased from the bordering villages of Fontenay-Près-Chablis (near Fourchaume) and Béru. It is a taut, compelling wine that reflects a mineral-tinged sharpness that the French describe as ‘goût de pierre à fusil’—gunflint—alongside aromas white hawthorn flowers and a cut of citrus.

The pedigree of the Moreau name dates to 1814 when barrel-maker Jean-Joseph Moreau founded a wine-merchant trading firm in Chablis. Although that original firm has changed hands several times, including a sale to Hiram Walker in 1985 and again to the Boissets of Nuits-Saint-Georges in 1998, the Moreau family never relinquished control of their vineyards. Domaine Christian Moreau Père et Fils began vinifying at the turn of the 21st century, and is now under the watchful care of Fabien Moreau: “Being the 6th generation of the family producing wines, was and still is a challenge for me, trying to avoid the pressure you could have with this wine heritage. But with the quality of the vineyard that my family passed on, the basis of the expression of our wines is here, and our work is to honor our terroirs.” Chablis 2018 ($36) is a cuvée built from grapes purchased from the bordering villages of Fontenay-Près-Chablis (near Fourchaume) and Béru. It is a taut, compelling wine that reflects a mineral-tinged sharpness that the French describe as ‘goût de pierre à fusil’—gunflint—alongside aromas white hawthorn flowers and a cut of citrus.

Domaine Christian Moreau

Domaine Servin

When you’ve been growing wine grapes in Chablis since 1547, post-Napoleonic upstart houses are the new kids on the block. With so many generations of winemakers and a pantheon of awards that span centuries, it is to be expected that the philosophy of Chablis, when uttered by a Servin, should be heeded. Says François Servin, the current winemaker, who was raised on vintages like 1929, 1947 and 1959: “A good Chablis is not a wine which is very elegant when young; Chablis for me is a wine which is good over 20 years.” This keen understanding of older vintages convinced him that malolactic fermentation combined with late bottling increases the ageing capacity of his wines. Chablis 2018 ‘Les Pargues’ ($27), planted in the vineyards behind the Premier Crus Vaillons and Montmains, employs a judicious blend of barrels and stainless-steel vats to create a wine that is concentrated and mineral-driven, showing natural mellowness, a touch of anise and lemon-peel balanced by smoke and earth.

When you’ve been growing wine grapes in Chablis since 1547, post-Napoleonic upstart houses are the new kids on the block. With so many generations of winemakers and a pantheon of awards that span centuries, it is to be expected that the philosophy of Chablis, when uttered by a Servin, should be heeded. Says François Servin, the current winemaker, who was raised on vintages like 1929, 1947 and 1959: “A good Chablis is not a wine which is very elegant when young; Chablis for me is a wine which is good over 20 years.” This keen understanding of older vintages convinced him that malolactic fermentation combined with late bottling increases the ageing capacity of his wines. Chablis 2018 ‘Les Pargues’ ($27), planted in the vineyards behind the Premier Crus Vaillons and Montmains, employs a judicious blend of barrels and stainless-steel vats to create a wine that is concentrated and mineral-driven, showing natural mellowness, a touch of anise and lemon-peel balanced by smoke and earth.

- - -

Posted on 2021.06.03 in France, Burgundy | Read more...

The Ascent of Corsican Wines: A Feast of Distinctive Varieties and Terroirs by 5 Leading Producers. (8-Bottle Memorial Day Pack $269, All Included.)

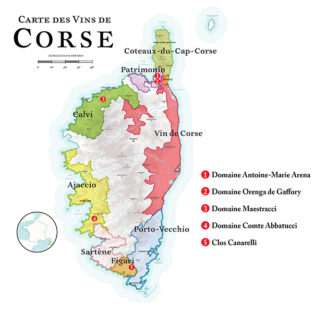

If you took the wine savvy of France, blended it with the climate of the Italian Riviera and stirred in the heritage of Greece, you might think you’d just created the Valhalla of Viniculture—a test tube appellation with Goldilocks conditions where everything is just right.

And you’d be close. Corsica began producing wine half a century before Christ, when traders from Anatolia planted vines in Aléria on Corsica’s western shore. The island was sold to France in 1768, a year before the birth of history’s most famous Corsican, Napoléon Bonaparte. But despite this alignment of stars, up until recently, Corsica did not produce much wine of note. Until well into the twentieth century, the primary grape planted throughout the island’s multitude of microclimates was Sciaccarellu, a variety whose value is primarily as a blender—as a stand-alone, it produces a simple, strawberry-perfumed wine that rarely shows much sophistication. In the later years of the twentieth century, however, government subsidies began to convince growers to reduce the numbers of vines they tended, and by 2003, that canny largesse resulted in more than 17,000 vine acres being uprooted. Combined with modern techniques like temperature-controlled fermentation, a new Corsican winemaking mindset has begun to take hold. Indigenous grapes still rule, including Niellucciu, derived from the Corsican word for ‘black and dry’; a close cousin of Sangiovese, but today, the hot, dry and mountainous island is the home to some of Mediterranean’s most iconic and spectacular wines.

Many of them are labeled AOP (Appellation d’Origine Protégée) rather than AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée), the French designation of top quality. As legal guarantees (limited production area, compliance with specific production standards and established name recognition) the terms are pretty much interchangeable; they are simply awarded by different authorities. First created in France in 1905 and recognized internationally since 1958, ‘AOC’ as a label-dresser is gradually being supplanted by the Europe Union’s AOP. ‘Vin de Pays’ is also being phased out in favor of the EU’s IGP (Indication Géographique Protégée), a term that covers wine from a designated area. In some cases, they are as good or better than AOP wines, but produced according to standards that may stray the strict regulations of AOP/AOC.

Many of them are labeled AOP (Appellation d’Origine Protégée) rather than AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée), the French designation of top quality. As legal guarantees (limited production area, compliance with specific production standards and established name recognition) the terms are pretty much interchangeable; they are simply awarded by different authorities. First created in France in 1905 and recognized internationally since 1958, ‘AOC’ as a label-dresser is gradually being supplanted by the Europe Union’s AOP. ‘Vin de Pays’ is also being phased out in favor of the EU’s IGP (Indication Géographique Protégée), a term that covers wine from a designated area. In some cases, they are as good or better than AOP wines, but produced according to standards that may stray the strict regulations of AOP/AOC.

These five Corsican producers are leading the pack in terms of quality over quantity. The 8-bottle pack ($269, All Included) is just in time for your holiday libation. It includes two of Domaine Maestracci’s, two of each of Domaine Orenga de Gaffory’s white and red, and one each of Domaine Abbatucci and Clos Canarelli. Domaine Arena’s Muscat is specially priced and isn’t part of the package.

Domaine Orenga de Gaffory

In parcels between the towns of Saint-Florent and Poggio-d’Oletta in the beautiful Patrimonio appellation in northern Corsica, Henri Orenga de Gaffory has been exploring unique terroirs since 1966. Finding them best expressed in traditional varietals, he dedicates his 150 acres to raising limited-yield Niellucciu, Vermentinu, Minustellu, Aleatico, Muscat and of course, the standby blending red, Sciaccarellu. Wine folks are familiar with at least a couple of them, but as to the rest, would be hard-pressed to bet on whether they were white or red. Here’s your hint: AOP Patrimonio 2019 White ($22) is 100% Vermentinu, grown in soils that are an equal blend of limestone, chalk and clay. It has an electric lemon-lime palate behind a white-flower bouquet tinged with brine. With another year of aging, honeyed wax notes will become more pronounced. AOP Patrimonio 2018 Red ($20) demonstrates the same terroir’s expression of Niellucciu—a native grape that must, by Patrimonio law, make up 90% of the blend with the balance in Grenache. It’s a robust and silky wine displaying fruits, peppery spice and licorice, tinged with mineral throughout.

In parcels between the towns of Saint-Florent and Poggio-d’Oletta in the beautiful Patrimonio appellation in northern Corsica, Henri Orenga de Gaffory has been exploring unique terroirs since 1966. Finding them best expressed in traditional varietals, he dedicates his 150 acres to raising limited-yield Niellucciu, Vermentinu, Minustellu, Aleatico, Muscat and of course, the standby blending red, Sciaccarellu. Wine folks are familiar with at least a couple of them, but as to the rest, would be hard-pressed to bet on whether they were white or red. Here’s your hint: AOP Patrimonio 2019 White ($22) is 100% Vermentinu, grown in soils that are an equal blend of limestone, chalk and clay. It has an electric lemon-lime palate behind a white-flower bouquet tinged with brine. With another year of aging, honeyed wax notes will become more pronounced. AOP Patrimonio 2018 Red ($20) demonstrates the same terroir’s expression of Niellucciu—a native grape that must, by Patrimonio law, make up 90% of the blend with the balance in Grenache. It’s a robust and silky wine displaying fruits, peppery spice and licorice, tinged with mineral throughout.

Domaine Orenga de Gaffory

Domaine Maestracci

Inland from Calvi, the granite plateau of Reginu provides a microclimate known in Corsica as ‘U Vinu di E Prove’. Conditions there are familiar (and ideal) to those who understand diurnal shifts as it relates to the production of fine wine. Daytime temperatures rise to sweltering heights, but nights are high-elevation cool; the combined effects develop the sugar and stubbornly hold onto the ripening fruit’s natural acidity. On the estate of an old olive grove, Roger Maestracci saw an opportunity for vineyards; essentially the only two crops which thrive under these conditions are olive trees and grape vines. The estate is now run by his granddaughter, Camille-Anaïs Raoust, who refers to ‘Clos Reginu’ AOP Corse Calvi 2019 ($19) affectionately as ‘Clos Reggie’. It is a blend of grapes that may have been unfamiliar to you before tasting through this package, but which may have become new friends: 30% Niellucciu, 30% Grenache, 15% Sciaccarellu, 15% Syrah, 5% Mourvèdre and 5% Carignan. It is a juicy, spicy, herb-scented, mouthwatering red wine that can serve as the foundation to any summer meal enjoyed outside.

Inland from Calvi, the granite plateau of Reginu provides a microclimate known in Corsica as ‘U Vinu di E Prove’. Conditions there are familiar (and ideal) to those who understand diurnal shifts as it relates to the production of fine wine. Daytime temperatures rise to sweltering heights, but nights are high-elevation cool; the combined effects develop the sugar and stubbornly hold onto the ripening fruit’s natural acidity. On the estate of an old olive grove, Roger Maestracci saw an opportunity for vineyards; essentially the only two crops which thrive under these conditions are olive trees and grape vines. The estate is now run by his granddaughter, Camille-Anaïs Raoust, who refers to ‘Clos Reginu’ AOP Corse Calvi 2019 ($19) affectionately as ‘Clos Reggie’. It is a blend of grapes that may have been unfamiliar to you before tasting through this package, but which may have become new friends: 30% Niellucciu, 30% Grenache, 15% Sciaccarellu, 15% Syrah, 5% Mourvèdre and 5% Carignan. It is a juicy, spicy, herb-scented, mouthwatering red wine that can serve as the foundation to any summer meal enjoyed outside.

Domaine Maestracci

Domaine Comte Abbatucci

In Corsica, the name ‘Abbatucci’ is seen as frequently as Washington in the United States, and for much the same reason—General Charles Abbatucci (from Ajaccio) was a hero of the French Revolution. The Domaine that bears the name is run by a direct descendent of the General, Jean-Charles Abbatucci. A fanatical exponent of the most eccentric of biodynamic techniques, the names of his blends are as flamboyant as the product behind the label—‘Cuvée Collection – Ministre Impérial’ Vin de France 2016 ($89) is composed of 22% Sciaccarellu, 18% Niellucciu, 15% Carcajolu-Neru, 15% Montanaccia, 12% Morescono, 10% Morescola and 8% Aleatico, drawing nuances from each of these fascinating varieties. Named for a leading military figure under Napoléon Bonaparte’s Premier Empire (who then became a consul under Napoléon III) the grapes are crushed by foot and macerated for 15 days before being aged in 600-liter demi-muids. The nose is an exotic combination of flower perfumes and exotic berry spice, and the wine unfolds with complexity, intensity and richness, with flavors of bramble fruits, cola, garrigue, good acidity and a backbone of toasted oak.

In Corsica, the name ‘Abbatucci’ is seen as frequently as Washington in the United States, and for much the same reason—General Charles Abbatucci (from Ajaccio) was a hero of the French Revolution. The Domaine that bears the name is run by a direct descendent of the General, Jean-Charles Abbatucci. A fanatical exponent of the most eccentric of biodynamic techniques, the names of his blends are as flamboyant as the product behind the label—‘Cuvée Collection – Ministre Impérial’ Vin de France 2016 ($89) is composed of 22% Sciaccarellu, 18% Niellucciu, 15% Carcajolu-Neru, 15% Montanaccia, 12% Morescono, 10% Morescola and 8% Aleatico, drawing nuances from each of these fascinating varieties. Named for a leading military figure under Napoléon Bonaparte’s Premier Empire (who then became a consul under Napoléon III) the grapes are crushed by foot and macerated for 15 days before being aged in 600-liter demi-muids. The nose is an exotic combination of flower perfumes and exotic berry spice, and the wine unfolds with complexity, intensity and richness, with flavors of bramble fruits, cola, garrigue, good acidity and a backbone of toasted oak.

Domaine Comte Abbatucci

Clos Canarelli

Yves Canarelli left a career in economics to return to his family’s wine estate on the somewhat brutal southern tip of Corsica, where temperatures have been known to soar to 109°F and rainfall rarely exceeds thirty inches annually; in the Figari appellation, the soil is essentially a sparse dusting of granitic red alluvia. Canarelli has championed the return of native varietals, which thrive in there in such conditions; he is one of the pioneers who advocated tearing out foreign grapes in favor of those first planted in Corsica since Phoenician times. Likewise, he uses only indigenous yeasts, and prefers slow, deliberate, precise fermentations, then leaves his reds unfiltered. AOP Corse Figari Rouge 2016 ($45) is a blend of 80% Niellucciu, 15% Syrah and 5% Sciaccarellu; it delivers a bold and intense presentation redolent of black cherry and dried blackberry with sweet almond, toasted spice and balsam in the finish.

Yves Canarelli left a career in economics to return to his family’s wine estate on the somewhat brutal southern tip of Corsica, where temperatures have been known to soar to 109°F and rainfall rarely exceeds thirty inches annually; in the Figari appellation, the soil is essentially a sparse dusting of granitic red alluvia. Canarelli has championed the return of native varietals, which thrive in there in such conditions; he is one of the pioneers who advocated tearing out foreign grapes in favor of those first planted in Corsica since Phoenician times. Likewise, he uses only indigenous yeasts, and prefers slow, deliberate, precise fermentations, then leaves his reds unfiltered. AOP Corse Figari Rouge 2016 ($45) is a blend of 80% Niellucciu, 15% Syrah and 5% Sciaccarellu; it delivers a bold and intense presentation redolent of black cherry and dried blackberry with sweet almond, toasted spice and balsam in the finish.

Clos Canarelli

Domaine Antoine-Marie Arena

When legendary Corsican producer Antoine Arena split his Patrimonio estate into sections, each of his sons got a piece. To his parcel, Antoine-Marie brought not only experience from his native Ile de Beauté, but his enological and viticultural studies in Hyères as well as internships in both Burgundy and Provence. He explains, “Working as a family is great, but the Corsican spirit of liberty and independence guided us in this decision.” Fulfilling both ideals, he constructed his new wine cellar across from the family home and has begun own legacy with a series of remarkable releases from the vineyard Morta Maìo—translated as ‘The Eldest Myrtle’, referencing the myrtle shrub found throughout Corsica. ‘Morta Maìo’ Muscat, Vin de France 2014 (Sweet White) ($50) is from Antoine-Marie’s first solo vintage, and shows the complexity of Muscat as a dessert wine; notes of sultana and apricot underscore silky peach and luscious beeswax, and in the finish, candied orange and bergamot. The wine is referred to as ‘non-mute’ or ‘vin doux naturel’ which in the parlance of the craft means that no alcohol is added; the 13.5% ABV comes entirely from natural grape sugars.

When legendary Corsican producer Antoine Arena split his Patrimonio estate into sections, each of his sons got a piece. To his parcel, Antoine-Marie brought not only experience from his native Ile de Beauté, but his enological and viticultural studies in Hyères as well as internships in both Burgundy and Provence. He explains, “Working as a family is great, but the Corsican spirit of liberty and independence guided us in this decision.” Fulfilling both ideals, he constructed his new wine cellar across from the family home and has begun own legacy with a series of remarkable releases from the vineyard Morta Maìo—translated as ‘The Eldest Myrtle’, referencing the myrtle shrub found throughout Corsica. ‘Morta Maìo’ Muscat, Vin de France 2014 (Sweet White) ($50) is from Antoine-Marie’s first solo vintage, and shows the complexity of Muscat as a dessert wine; notes of sultana and apricot underscore silky peach and luscious beeswax, and in the finish, candied orange and bergamot. The wine is referred to as ‘non-mute’ or ‘vin doux naturel’ which in the parlance of the craft means that no alcohol is added; the 13.5% ABV comes entirely from natural grape sugars.

Domaine Antoine-Marie Arena

- - -

Posted on 2021.06.01 in France, Corsica | Read more...

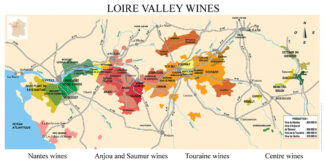

“The Garden of France” Bounty: Cabernet Franc & Pinot Noir Reds from Six Appellations in the Loire Valley. (6-Bottle Pack $259, All Included.)

The Loire Valley, the fabled stable for thoroughbred whites from Sancerre, Savennières and Vouvray, has often (and unfairly) been dismissed for its reds. In fact, cooler vintages of the past have sometimes resulted in erratic ripening, leading to thin, somewhat green-tasting reds made primarily from Cabernet Franc, Gamay, Malbec (here called Côt) and in the east—closer to Burgundy—Pinot Noir. But a gradually warming climate has made abysmal vintages increasingly rare, and coupled with overall improvements in viticulture, Loire has promoted its red wines from the chorus to a diva role, demonstrating as never before the potential that this marvelous appellation has to shine across the color spectrum.

Although red wines have been produced in the Loire throughout history, four appellations have demonstrated the strongest claim to fame. As improvements are happening everywhere, these four are only getting better, ranging in style from candy-apple crisp to voluptuous, rich and age-worthy. From west to east, they are Anjou (also known for its world-class rosé), fashionable, fragrant Saumur-Champigny, complex and tannin-rich Chinon and crunchy, spicy Bourgueil. Take a leap across the A20 motorway and the forests of Vierzon and you’ll find yourself in a sea of Sauvignon Blanc; Sancerre has earned its undisputed place in the pantheon of French white wine, and the nearby, lesser-known appellation of Menetou-Salon is often cited as a potential rival. But Pinot Noir planted in the chalky soils of Eastern Loire is finally coming into its own, both in quality and reputation. From certain producers, these succulent, fruit-driven reds crackle with acidity that shines through depths that are approaching those of Burgundy.

Six red wines from a choice of the best producers of Loire, ‘The Garden of France’, are featured in this week’s package (6-Bottle Pack $259, All Included)

Anjou

Anjou sprawls across 128 communes, mostly south of the towns of Angers in the west and Saumur in the east. Monasteries played the largest role in developing Anjou’s wine trade, as each enclave had its own walled vineyard, but it was French royalty who secured the region’s reputation, beginning nearly a thousand years ago when Henry Plantagenet became King Henry II of England. Anjou’s terroir is a matter of black and white: it’s divided into two subsoils as different as day and night. First, Anjou Noir, composed of blackish, dark, schist-based soil along the south-eastern edge of the Massif Armoricain, then, Anjou Blanc, lighter-colored soils made up of the altered chalk at the south-western extremity of the Paris Basin.

Clau de Nell is also centuries old, but its modern era began in 2008 when Anne-Claude Leflaive (owner and winemaker at Burgundy’s famed Domaine Leflaive) discovered the 20-acre property while on a promotional tour of her biodynamic approach to viticulture. She purchased the domain, finding the situation ideal: a south-facing knoll 295 feet above sea level, from which the Atlantic Ocean—75 miles away—is visible. The vines are planted in sandstone and red flint overlaying the soft limestone ‘tuffeau’ indigenous to the region; they range in age from 30-90 years. 2016 Clau de Nell “Cabernet Franc” ($59) has reached a prime drinking age; it shows rich, jammy raspberry and dusty pencil graphite, but tension on the palate is sustained as the acids remain charged and energetic.

Clau de Nell is also centuries old, but its modern era began in 2008 when Anne-Claude Leflaive (owner and winemaker at Burgundy’s famed Domaine Leflaive) discovered the 20-acre property while on a promotional tour of her biodynamic approach to viticulture. She purchased the domain, finding the situation ideal: a south-facing knoll 295 feet above sea level, from which the Atlantic Ocean—75 miles away—is visible. The vines are planted in sandstone and red flint overlaying the soft limestone ‘tuffeau’ indigenous to the region; they range in age from 30-90 years. 2016 Clau de Nell “Cabernet Franc” ($59) has reached a prime drinking age; it shows rich, jammy raspberry and dusty pencil graphite, but tension on the palate is sustained as the acids remain charged and energetic.

Clau de Nell – www.claudenell.com

Saumur-Champigny

Saumur has been a major focal point for the commercial wine trade since the 12th century, when (under Henry IV) it was the Huguenot capital. As an appellation, its terroir is rich in Loire’s characteristic calcareous rock, much of which was quarried over the centuries, leaving ideal cellars for aging Saumur wines. The hyphenated Saumur-Champigny is reserved for the 8 communes closest to the city of Saumur, and is restricted to around 3,700 acres, generally hilltop vineyards buffered against the west winds. It produces somewhat exclusive wines, representative of Saumur’s finest reds. Saumur-Champigny built around a firm foundation Cabernet Franc, with smaller additions of Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot d’Aunis permitted.

For a region dotted with beautiful historic homes, Château du Hureau is one of the few wine-producing châteaux among them. It is considered a top producer of Saumur-Champigny, with a milieu that is as breathtaking as the vineyard view, including the octagonal tower with mansard roofs and boar-headed weathervane from which the property derives its name. The estate contains multiple terroirs, and releases examples of each as ‘parcellaires’—wine from exclusive parcels. 2014 Château du Hureau ‘Lisagathe’ ($44) is named for fourth-generation winemaker Philippe Vatan’s two daughters Lisa and Agathe; it is made only in exceptional vintages. And only from selected portions of the estate’s best vineyards, located above the underground cellars. Full of mint-fresh young fruit, the wine expresses the classic smokiness of the AOP, with elegant undertones of chalk, flowers, pencil shavings and velvet-smooth tannins.

For a region dotted with beautiful historic homes, Château du Hureau is one of the few wine-producing châteaux among them. It is considered a top producer of Saumur-Champigny, with a milieu that is as breathtaking as the vineyard view, including the octagonal tower with mansard roofs and boar-headed weathervane from which the property derives its name. The estate contains multiple terroirs, and releases examples of each as ‘parcellaires’—wine from exclusive parcels. 2014 Château du Hureau ‘Lisagathe’ ($44) is named for fourth-generation winemaker Philippe Vatan’s two daughters Lisa and Agathe; it is made only in exceptional vintages. And only from selected portions of the estate’s best vineyards, located above the underground cellars. Full of mint-fresh young fruit, the wine expresses the classic smokiness of the AOP, with elegant undertones of chalk, flowers, pencil shavings and velvet-smooth tannins.

Château du Hureau – www.chateauduhureau.com

Bourgueil

As Loire is known affectionately as ‘the garden of France’, Bourgueil has been christened ‘the birthplace of Cabernet Franc’, which has been cultivated at the Abbey de Bourgueil since it was built on the Roman main road from Angers to Tours. Today, the appellation covers seven communes in the Indre-et-Loire along the right bank of the Loire, where it enjoys a remarkable microclimate due to the heavy forests that protect the vineyards from the north wind. Soil also cooperates; there are three distinct types: The islets of gravel in the alluvial terraces of the Loire on higher terraces, ancient, glaciated sand and clay/limestone soils from the ridge running along the north of the appellation. It is one of the few appellations in the Loire that produces predominantly red wines.

Catherine and Pierre Breton have been coaxing superlative wines from this terroir for decades; they cultivate 35 acres in the village of Restigné, just east of Bourgueil. Poetically, they grow mostly Cabernet Franc—the local term for this varietal is ‘Breton.’ Pierre remains the principal cellar master, although Catherine makes a series of cuvées under the label ‘La Dilettante.’ These wines are into three categories: Natural (for easy, early consumption), Classic (representing a profile of the appellation) and Wines of Terroir (vinified by individual parcel). 2018 Breton ‘Trinch!’ ($24) is an example of the former, produced from young-vine Cabernet Franc and referred to as ‘bistro-style’ for its quaffability. Indeed, ‘Trinch!” is a German variation on ‘cheers!” Lively, crisp and filled with juicy cranberry notes above an herbal-tinged core. A wine best enjoyed slightly chilled on any delightful and non-pretentious occasion.

Catherine and Pierre Breton have been coaxing superlative wines from this terroir for decades; they cultivate 35 acres in the village of Restigné, just east of Bourgueil. Poetically, they grow mostly Cabernet Franc—the local term for this varietal is ‘Breton.’ Pierre remains the principal cellar master, although Catherine makes a series of cuvées under the label ‘La Dilettante.’ These wines are into three categories: Natural (for easy, early consumption), Classic (representing a profile of the appellation) and Wines of Terroir (vinified by individual parcel). 2018 Breton ‘Trinch!’ ($24) is an example of the former, produced from young-vine Cabernet Franc and referred to as ‘bistro-style’ for its quaffability. Indeed, ‘Trinch!” is a German variation on ‘cheers!” Lively, crisp and filled with juicy cranberry notes above an herbal-tinged core. A wine best enjoyed slightly chilled on any delightful and non-pretentious occasion.

Domaine Catherine & Pierre Breton – www.domainebreton.net

Chinon

Playwright François Rabelais (a Chinon local boy made good) wrote, “”I know where Chinon lies, and the painted wine cellar also, having myself drunk there many a glass of cool wine.” That wine was likely red: though capable of producing wines of all hues, Chinon’s focus is predominantly red; last year, white and rosé wines accounted for less than five percent of its total output. Cabernet Franc is king, and 95% of the vineyards are thus planted. Rabelais’ true stage was set 90 million years ago, when the yellow sedimentary tuffeau, characteristic of the region, was formed. This rock is a combination of sand and fossilized zooplankton; it absorbs water quickly and releases it slowly—an ideal situation for deeply-rooted vines.

The Baudry family is also deeply-rooted in Chinon, although their education spans appellations outside the Loire, and extends as far in the wild red yonder as Tasmania. Bernard Baudry, the patriarch, studied oenology in Beaune and worked as a vine-tending consultant at Tours. His son Mathieu studied in Mâcon, then in Bordeaux after the year he spent working in Tasmania and California. The Baudry domain covers 80 acres across the AOP Chinon with additional parcels in Cravant les Coteaux; 90% of the property is planted to Cabernet Franc with the remaining to Chenin Blanc. Both father and son refer to the 2018 vintage as “Magnifique!” with a mild winter and springtime producing enough rainfall to recharge the groundwater which fell after a dry 2017. 2018 Baudry ‘Les Grézeaux’ ($25) pays homage to the gravelly soil beneath the parcel; earthy and rich, the wine showcases Cabernet Franc’s meatier persona. A rustic wine with great concentration and delightful spice, winemaker Baudry considers ‘Les Grézeaux’ to be textbook Chinon.

The Baudry family is also deeply-rooted in Chinon, although their education spans appellations outside the Loire, and extends as far in the wild red yonder as Tasmania. Bernard Baudry, the patriarch, studied oenology in Beaune and worked as a vine-tending consultant at Tours. His son Mathieu studied in Mâcon, then in Bordeaux after the year he spent working in Tasmania and California. The Baudry domain covers 80 acres across the AOP Chinon with additional parcels in Cravant les Coteaux; 90% of the property is planted to Cabernet Franc with the remaining to Chenin Blanc. Both father and son refer to the 2018 vintage as “Magnifique!” with a mild winter and springtime producing enough rainfall to recharge the groundwater which fell after a dry 2017. 2018 Baudry ‘Les Grézeaux’ ($25) pays homage to the gravelly soil beneath the parcel; earthy and rich, the wine showcases Cabernet Franc’s meatier persona. A rustic wine with great concentration and delightful spice, winemaker Baudry considers ‘Les Grézeaux’ to be textbook Chinon.

Domaine Bernard Baudry – www.bernardbaudry.com

Menetou-Salon

Unlike Loire’s ‘Big Four’ red wine appellations, Menetou-Salon produces mostly white wine, predominantly from Sauvignon Blanc. And unlike the Cabernet Franc-dominated reds from the west side of the river, the reds of Menetou-Salon are made from Pinot Noir, which expresses itself in light and strikingly fragrant wines. Extending across ten villages, the soils are predominantly Kimmeridgian limestone sediment. The climate here in the Central Loire is described as temperate with continental influences and wide variations in seasonal temperatures. Spring frosts—one time quite dangerous for finicky Pinot Noir—are becoming increasingly rare, leading to an explosion of popularity for these wines, much more reasonably priced than those from neighboring Burgundy.

M. Rabelais is not the only playwright connected with Loire wines; at the helm of Domaine Philippe Gilbert is Philippe himself, a ‘dramaturg’ (his description) who has written and produced for the stage. Today he is a winemaker foremost, having returned to the village of Faucards in Menetou-Salon to run the family estate, a winery whose history dates back to 1778 and his forefather Francois Gilbert. His 67 acres, sprinkled across prime sectors throughout Menetou-Salon, make it one of the most representative of the appellation. 2019 Domaine Philippe Gilbert ‘Hors Série’ ($37) comes from a parcel of Pinot Noir planted in 1980 by Philippe’s father; it opens beautifully, with a flamboyant and complex nose, still restrained in youth, but offering great potential behind cherry, spice, smoke and mineral-imbued flavors in a toasted oak frame.

M. Rabelais is not the only playwright connected with Loire wines; at the helm of Domaine Philippe Gilbert is Philippe himself, a ‘dramaturg’ (his description) who has written and produced for the stage. Today he is a winemaker foremost, having returned to the village of Faucards in Menetou-Salon to run the family estate, a winery whose history dates back to 1778 and his forefather Francois Gilbert. His 67 acres, sprinkled across prime sectors throughout Menetou-Salon, make it one of the most representative of the appellation. 2019 Domaine Philippe Gilbert ‘Hors Série’ ($37) comes from a parcel of Pinot Noir planted in 1980 by Philippe’s father; it opens beautifully, with a flamboyant and complex nose, still restrained in youth, but offering great potential behind cherry, spice, smoke and mineral-imbued flavors in a toasted oak frame.

Domaine Philippe Gilbert – www.domainephilippegilbert.fr

Sancerre

To many, red Sancerre sounds like an oxymoron, but connoisseurs know that a quarter of Sancerre’s vineyards are Pinot Noir. Like so many French wine regions that had the rug pulled out from beneath them during the phylloxera blight of mid-19th century, Sancerre found itself having to replant all its vineyards, which had—up to that time—been a red-wine producing zone; Pouilly Fumé, just across the river, was the Sauvignon Blanc powerhouse. For a multitude of reasons, most of the estates replanted using that varietal, and as the white wines of Sancerre soon eclipsed those of her sister commune, there was not much incentive to look back. The reds became an afterthought, and Pinot Noir is not the sort of grape that suffers scorn easily. In the ‘90s, however, certain producers (notably Alphonse Mellot Jr.) began to experiment with lower and more selective yields, and since then, the quality has improved astronomically.

Cousins, Jean-Laurent and Jean-Dominique Vacheron have no issue learning from the masters; having converted entirely to biodynamic viticulture in 2005, they have opted to use techniques from the Burgundy playbook to encourage the most potential from their scant thirty acres of Pinot Noir, which sits primarily on flinty silex soils. 2018 Domaine Vacheron ($56) is nicely structured with focused plum and sour cherry in the mid-palate and a rich, pure and persistent finish.

Cousins, Jean-Laurent and Jean-Dominique Vacheron have no issue learning from the masters; having converted entirely to biodynamic viticulture in 2005, they have opted to use techniques from the Burgundy playbook to encourage the most potential from their scant thirty acres of Pinot Noir, which sits primarily on flinty silex soils. 2018 Domaine Vacheron ($56) is nicely structured with focused plum and sour cherry in the mid-palate and a rich, pure and persistent finish.

- - -

Posted on 2021.05.20 in France, Loire | Read more...

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Aglianico, Albarín Blanco, Albillo, Aleatico, Alicante Bouschet, Altesse, Arbanne, Arcos, Aubun, Auxerrois, barbera, Beaune, Bonarda, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Chenin Blanc, Corvina, Corvinone, Cot, Erbamat, Ferrol, Fiano, folle Blanche, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Fumin, Garganega, Garnacha, Gewurztraminer, Godello, Grenache, Grolleau, Jacquère, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Lladoner Pelut, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marsanne, Melon de Bourgogne, Mencía, Merlot, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montepulciano, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Mourvèdre, Muscadelle, Nero d'Avola, Palomino, Parellada, Pecorino, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pinot Auxerrois, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Rondinella, Rose, Roussanne, Sangiovese, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, trepat, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Viognier, Viura, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012