From Rock to Wine: Six Domaines Showcase Alsace Grand Crus’ Singularity of Character + Pinot Noir Is Taking Root in Alsace

As a gold medal represents the highest award that an Olympic athlete can win, in the wine world, Grand Cru is the highest designation to which a plot of land can aspire. If you are a lover of French wine (a rhetorical point since you are reading these words), it is no doubt a term that is both mysterious and sacred, as various pieces of earth have been considered in religious tradition from time immemorial; Kashi Viswanathan in India, Mecca in Arabia and Lourdes in France. Although not imbued with supernatural powers of healing, Grand Cru vineyards are saturated in terroir that is considered the ne plus ultra of any wider appellation.

At least, that’s the theory. In our continued exploration of Alsace this week, we find that Grand Cru status has an additional determining factor: Politics. This is not to suggest that these are not the finest wines that Alsace can produce, only that it may not be a guarantee of it, at least compared to Burgundy. Alsace has enormous geological diversity within a fairly constrained area, and each Grand Cru may rightly claim its own unique identity rather than an absolute commitment to rules that would ensure top quality.

And yet, an equal number of vignerons within a designated Grand Cru feel that the existent rules are too harsh.

Regarding this status, Hubert Trimbach, from his domain’s famous address in Ribeauvillé, once said about the Crus, “We are opposed! There is not enough discipline; yields are too high; quality is questionable; prices are ridiculous and criminal … This is a political time-bomb. No, no and no.”

This is a debate that you can moderate yourself, and fortunately, at a reasonable cost. Unlike Burgundy’s Grand Crus, which will usually set you back three figures, even the most prestigious Alsatian Grand Crus are generally around a hundred dollars and most are considerably less than that, as this week’s selection will prove.

The Grand Crus: Singularity of Character

As viewed by an Alsace outsider, who may be able to instantly distinguish between an Echézeaux and a Chambertin, the problem with learning Alsace Grand Crus that are just so damn many of them. Beginning with the Schlossberg of Kaysersberg, the classification first peeked out from under the bed in 1975. A list of 24 new Grand Crus was added in 1983, followed by a further 25 in 1992. Ultimately, Kaefferkopf was added in 2007 to make a total of 51 Alsace Grand Crus.

Combined, they equal about 5.5% of the total vineyard area in Alsace, whereas in Burgundy, Grand Cru appellations account for less than 1%.

And once you’ve digested the nuts and bolts of Alsace Grand Crus, you can start in on the next course: Alsace Premier Crus. At first pass, you might think this is easy since there are none. But to date, 160 applications have been accepted by the INAO, and these are currently undergoing the rigorous approval process.

In fact, the whole hierarchy system in Alsace may soon see a profound change: Proposed is a new system wherein wines with a complementary denomination would be removed from the regional category and upgraded to a new level similar to Burgundy ‘Villages’ wines. They would be recognized as independent AOPs with specific production rules—‘cahier des charges’—and some high-quality lieux-dits that have shown consistency would be gathered into a new Premier Cru (1er Cru) category, with specific production rules as well.

The irony is that the proposed 1ers Crus vineyards will be delimited in a stricter way than the Grand Crus were, and there is a danger that some will out-perform the lesser Grand Crus.

As it is now, however, Grand Cru will remain as the sole representation at the top tier in Alsace’s exclusivity pyramid, but in the mind of Jean Hugel (of the family-run domain in Riquewihr): “There should have been 20 Grand Crus right from the beginning, and the rest should have been Premier Cru.”

Sugar: The Word That Cannot Speak Its Name

In Alsace, sugar has bedeviled winemakers and consumers for eons, although new regulations might be a little sugar to help the medicine go down.

According to Marc Hugel (Hugel & Fils): “When I first started in the trade 35 years ago, most of our wines contained three grams of sugar per liter or less. Now, most have more. I think there is correlation between our move toward sweet wines and low prices.”

Although dry wines is the purported goal of winemakers to meet a demand for food wine, warmer weather patterns have pushed ripeness, forcing producers to leave residual sugar to keep alcohol levels in check. Extra sugar can also hide; four grams per liter can seem bone dry with high enough acid levels. Another factor is that as wine ages, it tastes less sweet on the palate, a phenomenon that even Marc Hugel can’t explain. “Sometimes I leave residual sugar to keep alcohol moderate, but upon release six or seven years later, it tastes dry.”

The Grand Crus were defined at a time when getting to ripeness was problematic, so they are generally the sites that achieve greatest ripeness, often south-facing hillsides. An outdated regulation requires potential alcohol to reach 10% at harvest, but today it’s more of a problem to restrain alcohol. Even the most committed producers admit that it’s mostly impossible to get completely dry Pinot Gris or Gewürztraminer from Grand Cru sites: “Pinot Gris ripens very rapidly. Sometimes you say you harvest in the morning and it’s dry, you harvest in the afternoon and it’s sweet,” says Étienne Sipp (Louis Sipp). Marc Hugel adds, “Gewürztraminer will reach 13-14% when Riesling gets to 11%. It’s better to have 14% alcohol and 7 g/l sugar than 15% alcohol and bone dry.” Céline Meyer (Domaine Josmeyer) says, “If Gewürztraminer is completely dry it’s not agreeable because it’s too bitter.”

Now, a standardized sweetness guide will be required on all labels of AOP Alsace beginning with wines produced from the 2021 harvest. One option is for labels to contain a visual scale with sweetness levels and an arrow clearly pointing to one specific level. Slightly more information is available in the second option, a designation on each bottle of either Dry (sec): sugar content does not exceed 4 g/l; Medium-Dry (demi-sec): sugar content 4 g/l and 12 g/l; Mellow (moelleux): sugar content of the wine is between 12 g/l and 45 g/l and Sweet (doux): sugar content of the wine exceeds 45 g/l.

Domaine Albert Mann

According to David Schildknecht of The Wine Advocate, “The Barthelmé brothers, Jacky and Maurice, have maintained their position near the forefront of Alsace viticulture by farming a range of relatively far-flung and outstanding vineyards as well as offering excellent value virtually throughout their range.”

The fifty acres for which the Barthelmé are responsible are highly regarded throughout Alsace. Headquartered in the village of Wettolsheim near Colmar, the spirit animal of the operation is Albert Mann, Maurice’s father-in-law. He was the first to hit upon the idea of using modern production tools without neglecting the constraints of the land and his philosophy was to make wine using the elements of the soil, without the help of fertilizers. The Barthelmé brothers have embraced his beliefs and are now at the forefront of organic/biodynamic Alsace producers. The goal of the estate is to produce wine that is in harmony with nature: “Wine is the memory of the grape and is capable of transmitting the taste of the earth.’

The brothers began practicing biodynamic viticulture in 1997 in three of their Grand Cru vineyards, receiving certification from Biodyvin in 2015. This labor-intensive technique is intended to give the wine the purest reflection of its terroir and own identity. Says Maurice, “In ploughing the vineyards, we encourage the roots to descend to a maximum depth to capture the beneficial mineral elements from degraded rock below. Our holdings are divided up into a myriad of distinct plots, thus ensuring that each wine is reflective of their precise origins, while remaining as complex and multi-faceted as possible.”

The domain owns vines in five separate Grand Cru sites.

Hengst and Schlossberg are two of the better known. Hengst (meaning stallion) has a southeast orientation and shallow stony/calcareous soil while Schlossberg, with its steep, terraced slopes of granite, sand and shale, yields particularly expressive wines with pronounced floral bouquets. Both sites produce wines that age superbly.

Grand Cru Hengst

The Hengst Grand Cru lies in the commune of Wintzenheim, at the same latitude as Colmar, below the Hohlandsbourg Castle where altitudes are between 900 and 1200 feet on a steep, homogenous slopes. The vineyard faces south-east and benefits from the warm, dry Colmar microclimate.

Hengst soil structure is composed of oligocene conglomerates and lattorfian-interbedded marl. Although it is located in an early ripening sector, Hengst ripens grapes slowly and resists the development of noble rot. Rich in marl and trace elements, vines develop a high resistance to drought and easily avoid water stress. A significant presence of pebbles ensures that the soils are well drained. The high alkalinity of the soil and limestone substrate (45% active lime) may sometimes cause chlorosis (yellowing leaves) despite the soil being iron rich.

Hengst wines are powerful, complex and dense with bright acidity on the finish. They have great keeping potential, developing more expression with age.

Domaine Albert Mann, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Hengst Pinot Gris ($47)

Domaine Albert Mann, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Hengst Pinot Gris ($47)

Mann’s vines in Hengst are near the depression at the Cru’s center; the vineyard generally runs south-easterly with complicated geological strata that are quite visible to the naked eye. The wine is extremely concentrated and exotic with ripe mangoes, peaches and a core of preserved pears giving softness to the bright acids.

Grand Cru Furstentum

The Furstentum hillside nestles in the bosom of the Kaysersberg valley, where, with a southwest exposure, it is protected from the winds and thrives in an island of Mediterranean calcicolous vegetation. The brown, limestone soil is pebbly and porous with outcrops of bedrock. Covering 75 acres, the marl-limestone-sandstone originates in the Middle Jurassic period, covered at the end with Tertiary conglomerates.

The Cru has a steep grade (37%) to optimize the sun on a soil, allowing heat to accumulate through the day. It is primarily planted to Riesling, Gewürztraminer and Pinot Gris and produces wines of great finesse and remarkable aromatic weight.

D omaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Furstentum Pinot Gris ($45)

omaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Furstentum Pinot Gris ($45)

Furstentum’s iconic floral and blossom signature perfectly offsets the pear/apple of Pinot Gris. Approximately 35% of Alsace’s Grand Cru vineyards are planted to Pinot Gris, and this is a marvelous ambassador for the reason why. The intense, super-ripe pear notes are shored up by fresh pineapple and tangerine.

Domaine Albert Mann ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Furstentum Gewürztraminer ($45)

Domaine Albert Mann ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Furstentum Gewürztraminer ($45)

‘Vieilles Vignes’ refers to the fact that these vines are at least 45 years old; it is an archetypal Furstentum Gewürz with violet on the nose with a long-lasting backbone of Mirabelle plum, lychee, peach and unctuous lime marmalade, finishing on a slightly bitter note.

Grand Cru Steingrubler

Steingrubler vineyard sits just to the west of the village of Wettolsheim in the Haut-Rhin department of France. It is one of the more southerly of the Grand Cru sites in Alsace and covers an area of 56.7 acres, predominantly planted to Gewürztraminer. Steingrubler is one of four Grand Crus which run in a line just to the south-west of Colmar; Eichberg, Pfersigberg and Hengst are the other three. Pfersigberg is one of the largest Grand Crus in Alsace and for comparison Steingrubler is less than one-third of its size.

Sitting on the lower slopes of a granite promontory jutting out from the eastern Vosges, a topographical feature mirrored about a mile to the south at the Pfersigberg vineyard and again to the north in Hengst. The slopes enjoy a south-easterly aspect and soils have a heavy colluvial content—rough scree made up of granite, marlstone and limestone that improve drainage of the already dry site. The sandier soils higher up are mostly planted with Riesling, which makes up 26% of the vineyard. The richer clay and limestone below is well-suited to Gewürztraminer, making up 52% of the vineyard. The remaining 22% is Pinot Gris.

As well as being one of the driest vineyard sites in Alsace, Steingrubler is also considered a later-ripening vineyard. In the early-ripening vintage years the wine may be concentrated but remain elegant, combining aromas of candied fruit and, for Gewürz, bitter almonds.

Domaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Steingrubler Gewürztraminer ($45)

Domaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Steingrubler Gewürztraminer ($45)

Bright and perfumed with tropical breeze: Mango, passion fruit, crystallized papaya and fresh ginger dominate. Both silky and crystalline, the flavors of exotic fruit and sweet spice showcase magnificently why the Steingrubler is one of Alsace’s best Grand Crus for Gewürztraminer.

Grand Cru Schlossberg

With 200 acres under vine, Grand Cru Schlossberg is the largest of the region’s Grand Cru sites as well as the oldest, being the first Alsace vineyard granted Grand Cru status when classification began in 1975. It inherited its title from the castle (‘schloss’ in German) at its western edge, which it has stood guard over Kayserberg and the Weisbach Valley for 800 years. The vineyards are even older than the castle as the Roman colonists tended vines here more than 1,500 years ago.

The Schlossberg hillside is composed largely of granite, with the upper layers in an advanced state of decomposition. As a result, the topsoils contain a high proportion of coarse granitic sand, rich in potassium, magnesium and phosphorus of which are minerals that are found in few other vineyards. The distinctive style of Schlossberg Riesling wine is attributed largely to this unusual soil composition. As referenced, apart from a few notable exceptions, all Alsace Grand Cru wines are varietals and may be made from Gewürztraminer, Pinot Gris, Muscat or Riesling, and Schlossberg has each of these varieties planted, although it is particularly well known for its Riesling. It is entirely separate from the smaller Wineck-Schlossberg, two miles to the south.

Domaine Albert Mann, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Schlossberg Riesling ($88)

Domaine Albert Mann, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Schlossberg Riesling ($88)

A substantial, acid-ripped Riesling that, while exuding youth, is built for the ages. The nose is marked by hawthorn and lime blossom, while on the palate, citrus peel is underlined by a minerality that beautifully expresses the granitic terroir.

Domaine Weinbach

Named after the little stream which runs through the property, Domaine Weinbach was first planted with vines in the 9th century and established as a winery by Capuchin friars in 1612. After being sold as a national property during the French Revolution, it was acquired by the Faller brothers in 1898, who then left it to their son and nephew, Théo Faller. Following his death in 1979, his wife Colette and daughters Catherine and Laurence continued the family’s passion for great wines until the untimely deaths of Colette and Laurence. Since 2016, Catherine has led the estate winery with her sons, Eddy and Théo.

Domaine Weinbach owns 65 acres of vineyards in the Kaysersberg valley in the Haut-Rhin of Alsace at between 600 and 1300 feet above sea level. Vines are grown organically with a view to quality rather than quantity and grapes. Unlike most producers in Alsace, who purchase from négociants, Weinbach vinifies only estate grown grapes, and their aging philosophy is best described as passive, carried out in huge old oak foudres, a technique they believe allows each climat and each terroir (along with the other unique characteristics of grape and vintage) to shimmer through and produce elegant and sophisticated wines.

Domaine Weinbach, 2020 Alsace Grand Cru Schlossberg Riesling ($79)

Domaine Weinbach, 2020 Alsace Grand Cru Schlossberg Riesling ($79)

Wild herb and dried citrus zest drive a sensationally crisp wine with hints of mandarin orange, persimmon, jasmine and chamomile. The fruit is ripe and the acidity is vibrant, leading to an intense, long finish flecked with salty minerality.

Domaine Meyer-Fonné

Félix Meyer is one of those winemakers whom you sense is a star that will grow ever brighter with every vintage. He is the third generation in his family to be making wine since his grandfather founded Meyer-Fonné in the late 19th century and since taking over 1992, Félix has modernized equipment, developed export sales and is currently driving the family’s holdings deeply into the best vineyards of Alsace.

According to Félix, “Our vineyard covers eighteen hectares and seven communes, where the nature of the soils, the relief of the land and levels of exposure are varied. The soils range from poor quality filtering alluvial deposits (Colmar) to rich, deep clayey sandstone land in Riquewihr, with granite in between in Katzental, while the relief ranges from the flats of Colmar to the steeply sloping Katzental. The degrees of exposure are also very varied, ranging from the cooler western part which is suitable for the earlier vine types to the south-facing part which is very warm and sunny. This great variety of terroirs constitutes a distinctiveness and a richness in relation to many of the French vineyards.”

A stickler for detail with an overriding sense of responsibility, both his family and the earth, he makes his home in Katzental, known for its distinctive granite soils. With this remarkable terroir beneath his feet, Meyer has developed a knack for mixing wine from various of his parcels into complex and balanced cuvées. Among his cellar tricks is leaving wine to age on lees in large, older foudres, as was once the tradition in Alsace. All of Meyer’s bottlings are characterized by their stunning aromatics and signature backbone of minerality and electric acidity.

Grand Cru Wineck-Schlossberg

Wineck-Schlossberg lies between the communes of Ammerschwihr and Katzental in heartland of the Alsace. It is particularly known for its aromatic Riesling and Gewürztraminer. It is among a cluster of five sites immediately west of the region’s wine capital, Colmar, along with Brand, Florimont, Sommerberg and Kaefferkopf.

Wineck-Schlossberg vineyards cover 65 acres overlooking Katzental. The hillside is composed largely of granite like nearby Sommerberg, with the upper layers in an advanced state of decomposition. As a result, the topsoils contain a high proportion of granitic sand, rich in minerals not found in most other Alsace vineyards. The vines enjoy a south-southeasterly aspect, meaning that the vines are exposed to the ripening rays of the sun throughout the morning and into the afternoon. The slopes are nestled in a high sided valley which gives the site—already in the rain shadow provided by the Vosges mountains—plenty of protection from wind.

The wines are dry, showcasing a subtle balance between, minerality and crystalline fruit.

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2016 Alsace Grand Cru Wineck-Schlossberg Riesling ($45)

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2016 Alsace Grand Cru Wineck-Schlossberg Riesling ($45)

The crumbly binary mica granite known as ‘de Turckheim’ in the Wineck-Schlossberg Grand Cru gives this wine a pure and delicate with (as suits the winemaker’s name) Meyer lemon and fresh tarragon lacing white peach, grated ginger, lemon curd and stone notes.

Grand Cru Schoenenbourg

Schoenenbourg lines the south-facing hillside above the communes of Riquewihr and Zellenberg; at 132 acres it is one of the larger of Alsace’s Grand Cru sites. Although it is viewed as being at the core of Alsace’s prime vineyard belt, located in a crop of about ten Grand Crus between the towns of Colmar and Ribeauvillé, Schoenenbourg is slightly removed from the lower slopes of the Vosges Mountains where most of the other Alsace Grand Crus are to be found. The slopes rise steeply from 870 feet to around 1,250 feet from the northern walls of Riquewihr.

The soils are varied across this long, thin site, leading to variability in Schoenenbourg wines depending on the exact parcels of land where the grapes were grown. Marlstone, locally called Keuper after the geological period of the same name, is a dominant soil type, often covered by a fine layer of sandstone. The more unusual soil component here is gypsum, deposited when oceans covered the area during the Jurassic period more than 150 million years ago. Gypsum brings a particular combination of mineral richness to the wines; it also has a higher water-retention rate and is the secret behind Schoenenbourg’s botrytized wines from, sold as Selections de Grains Nobles.

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2017 Alsace Grand Cru Schoenenbourg Riesling ($50)

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2017 Alsace Grand Cru Schoenenbourg Riesling ($50)

Only ten cases of this wonderful elixir make it to the United States every year; it comes from a third of an acre of 30-year-old vines planted on the Cru’s typical ‘marne verte de Keuper’ soil. It is fermented in temperature-controlled stainless-steel tanks and oak barrels over a period of 1-3 months. It is a precise, dry, mineral-focused Riesling combining ripe apple flavors with bright lemon and shows subtle chalk on the finish.

Domaine Mann

After stints in Côte-Rôtie and Champagne, where he learned the value of biodynamics from Bertrand Gautherot, Sébastien Mann has been making wine at the family estate since 2009, taking over from his father. He says, “I think that thanks to biodynamics, we have succeeded in bringing an additional element to our vines. My father made wines essentially linked to the earth; I have a much more holistic style, linked to the stars.”

Domaine Mann’s 32 acres were founded upon the theory that in order to produce terroir-driven wines with aging potential, legally allowable yields have to be cut in half. From the outset, the estate produced 35 cuvées, one for each parcel.

“The style of the wines changed very quickly when I came on board,” Sébastien maintains. “95% of the wines we produce now are dry. It was not an easy task, since Alsace is one of the warmest and driest regions in France. Grapes can easily ripen with a high sugar level. I don’t think my father could imagine that with biodynamics we would be able to achieve such a great evolution, achieving phenolic maturity while making dry wines.”

Grand Cru Pfersigberg

Pfersigberg is the third-largest Alsace Grand Cru, covering 184 acres immediately to the west of Eguisheim. It is overlooked by the Trois Donjons the city’s three towers once used by agrarians as a timepiece, noting the position of their relative shadows to track the progress of the sun.

Pfersigberg slopes are some of the most gentle in Alsace, rising from 720 feet at their eastern edge to a little over a thousand feet in the west. There is a marked difference between the topography here and the steep, almost unmanageable slopes of Grand Cru sites of Zinnkoepfle and Rangen. The soil is predominantly limestone and marl with a higher quantity of clay than is usual this far away from the river basin. This clay reduces the drainage efficiency of the local soils.

Pfersigberg is one of the driest vineyard sites in Alsace and the climate of the area overall is continental, with marked low rainfall due to the shadow cast by the Vosges. The mountains also provide protection from the prevailing westerly winds.

The site produces wines with ample body and dense, straight-forward acidity marked by citrus fruits, notably limes. Nervous and willowy, the wine’s purity enhances the aromas of flowers and the minerality expresses itself in the length.

Domaine Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Pfersigberg Riesling ($69)

Domaine Mann, 2018 Alsace Grand Cru Pfersigberg Riesling ($69)

The techniques used in this dry, delightful wine include manual harvesting in boxes, gentle and long pressing times, natural fermentation on indigenous yeasts and aging on the lees for a year. The wine is juicy and transparent, presenting white peach and lime beside piquant hints of caraway, peach kernel, citrus zest and chalk.

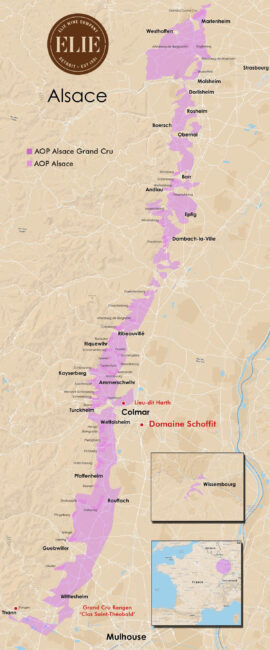

Domaine Schoffit

To call a man a ‘pioneer’ who cultivates wine country that has been famous for eight hundred years (vintage 1228 was described as ‘extremely good; so hot you could fry an egg in the sand’) may seem a stretch, but the spirit that impelled Bernard Schoffit to purchase 16 acres around Clos St. Theobold belongs to a frontiersman. Previously abandoned because the slopes were deemed too steep to work, the vines in question (in Rangen de Thann AOP) grew on a plot of soil that has been likened to Montrachet and Chambertin. And from this forbidding site, relying on extremely low yields, he is making extraordinary wine with each cépage.

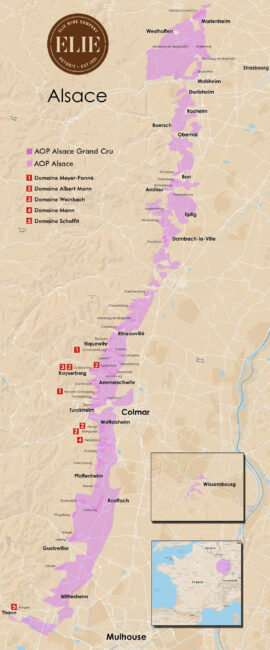

In addition, Schoffit raises grapes in the lieu-dit Harth, an alluvial terroir close to the commercial area of Hussen in northern Colmar, and three acres in the granitic Grand Cru Sommerberg to the south of Katzental and to the north of Niedermorschwihr. In Harth, Schoffit tends 80 years old Chasselas vines, of which a few percent are replanted each year as an illustration of Schoffit’s long-term perspective

Based near Colmar, Bernard took the winery over from his father Robert and his son Alexandre is now a co-owner. Demonstrating the estate’s commitment to sustainable agriculture Alexandre maintains, “All our vineyards are organic, and we also started to work biodynamic a few years ago. In order to show more transparency, I decided in 2016 to launch the official certification process, but for administrative reasons it was stretched over different years. The first wines officially labeled fully organic will be some cuvées of the 2019 vintage (Harth Riesling and Harth Pinot Gris for example), and the rest of the classic range will follow in the 2020 vintage. For the Grand Crus, it will be from the 2022 vintage. The official certification for biodynamic is in progress and we are still waiting to know from when we will be able to use it on the labels. But for now, Domaine Schoffit gives the assurance that we are both bio and biodynamic!”

Grand Cru Rangen

Volcanic upheaval is the name of the game at inconspicuous hillside adjacent to the town of Thann, making it a geological anomaly in the Vosges Mountains. But there even more bang for that buck—while ploughing Rangen acres that had abandoned for multiple generations, Olivier Humbrecht (Domaine Zind-Humbrecht) uncovered three unexploded bombs from World War II. Dotting the eastern slopes of the Vosges Mountains and is notable for more than just its terroir: Rangen is the only site in Alsace to be classified as Grand Cru in its entirety, and is home to the highly respected Clos Saint Urbain and Clos Saint Théobald vineyards.

In Rangen, the altitude climbs higher (1100 to 1525 feet) and the slopes have an average gradient of 60%. It is predominantly planted to Pinot Gris, the variety that accounts for 57% of vines; Riesling represents about a third of the site while Gewürztraminer is 10%. Despite its southerly aspect, Rangen is late-ripening, mainly due to its higher rainfall and cool winds which also make the site more prone to botrytis and its attendant Sélection Grains Nobles and/or Vendanges Tardives sweet wines.

The late-ripening terroir also increases power (and often alcohol) in the wines. Wines from Rangen are often described as having a ‘smoky’ taste.

Domaine Schoffit, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Rangen ‘Clos Saint-Théobald’ Riesling ($59)

Domaine Schoffit, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Rangen ‘Clos Saint-Théobald’ Riesling ($59)

The volcanic soils of Rangen, characterized by their low clay content, lie beneath one of the warmest plots in the region, a combination that generally pushes this Grand Cru to the top of the list. At 14.3% abv, it is precise and potent in comparison to a German Riesling, showing dried peach, lemon curd, fresh lime and Rangen’s classic, slightly resinous aromas of fresh rosemary.

SGN: The Quintessence of Alsace Wines

Alsace’s semi-continental climate sees very little rain and—especially in the autumn—remarkably consistent sunshine. This is ideal for extended ripening as well as the development of noble rot. Particularly suited to these effects Riesling, Muscat, Pinot Gris and Gewürztraminer d’Alsace, often several weeks after the normal harvest time when the berries are ultimately at their best.

Sélections de Grains Nobles grapes are obtained from harvesting grapes with noble rot where the driest berries are kept. This particularly high sugar content creates more discreet varietal flavor with enhanced intensity, complexity and remarkable length.

After substantial efforts undertaken by wine-makers, the official recognition of Sélections de Grains Nobles was made by a ministerial decree; March 1, 1984.

Domaine Albert Mann ‘Le Tri’, 2010 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Sélection de Grains Nobles SGN Pinot Gris ($126) 375 ml

Domaine Albert Mann ‘Le Tri’, 2010 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Sélection de Grains Nobles SGN Pinot Gris ($126) 375 ml

The residual sugar is met by a near-doubling of acidity leading to a beautifully balanced dessert-style wine powered by notes of candied lime peel, grapefruit marmalade, honey, marzipan, lanolin and vanilla.

The Upside of Climate Change: Pinot Noir is Taking Root in Alsace

Global warming is potentially an earth-ending reality, but if anybody is snatching victory from the jaws of defeat, it is Alsace. According to winemakers there, the overall increase in temperature, though only a few degrees, is enough to allow their Pinot Noir to ripen more fully, producing wines with greater concentration, both in flavor and color.

This is a remarkable turn of events, since 90% of all wines produced in Alsace are white, made from the multitude of varieties mentioned above. The surprise of the century, Pinot Noir d’Alsace quality levels not only from warmer, dryer summers, but because of a dedication of winemakers to plant the grape in higher-quality growing areas once reserved for prized white varieties. Pinot Noir plantings are skyrocketing in Alsace, rising from 2% in the last century to more than 10% today.

If the trend continues (and there is no reason to suppose it won’t) we will likely be introduced to a Pinot Noir Grand Cru, and sooner rather than later—likely before the end of the planet.

Domaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Pinot Noir lieu-dit ‘Clos de la Faille’ ($88)

Domaine Albert Mann, 2018 Alsace Pinot Noir lieu-dit ‘Clos de la Faille’ ($88)

The Clos de la Faille monopole is just under three acres located near the Grand Cru Hengst; it is the only Clos in Alsace planted with 100% Pinot Noir. It is divided into three sections—the upper part consisting of pink, mottled and calcareous sandstone; in the middle, there is grey shell limestone with a very fine grain and yellow Jura rock, and in the lower part, a mixture of Vosges sandstone and white and pink quartz; the vines were planted between 1998 and 2002. The wine shows a nice leather and forest-leaf profile, opening to blackberry, cedar, smoke and chocolate.

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2017 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Pinot Noir ($48)

Domaine Meyer-Fonné, 2017 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Pinot Noir ($48)

Among the best of Alsace’s new guard of Pinot Noirs, this seductive wine, with seductive notes of tea leaves, strawberries and blackberries, is in the class of many Premier Cru Burgundies. It is spectacular now, and should improve for a decade.

Domaine Weinbach, 2019 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Pinot Noir ($110)

Domaine Weinbach, 2019 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Altenbourg’ Pinot Noir ($110)

Lieu-dit Altenbourg lies at around 800 feet elevation just below Grand Cru Furstentum. Wines from this terroir are made from grapes harvested in the Kientzheim-Kaysersberg valley, just below the foothills of the Vosges Mountains. Although it does not possess Grand Cru status itself, Altenbourg is considered as good as many Crus that do hold the title. The wine is rustic and redolent with scents of cranberries, strawberries and raspberries with supple, soft tannins.

Domaine Weinbach ‘S’, 2019 Alsace Pinot Noir ($110)

Domaine Weinbach ‘S’, 2019 Alsace Pinot Noir ($110)

According to Catherine Faller, Domaine Weinbach’s third-generation proprietor, “Pinot Noir is to red wine what Riesling is to white wine. Neither copes with mediocrity.” As a result, the goal is low yields and perfect grape maturity. The grapes in the ‘S’ series were sourced from the Grand Cru vineyard Schlossberg and offer elegant, fresh cherry and herb on the nose and a supple mouthfeel with some sappiness.

Domaine Schoffit ‘Vieilles Vignes Vendange Entière’, 2018 Alsace Pinot Noir ($33)

Domaine Schoffit ‘Vieilles Vignes Vendange Entière’, 2018 Alsace Pinot Noir ($33)

‘Vendange Entière’ refers to whole-cluster fermentation—a cellar technique intended to make a given wine more complex, weaving in spicy and herbal while adding candied and airy fruit and tannin structure, and also, to smooth out high acidity. In short, it is a method winemakers use to override anything lacking in a cool climate Pinot. Here, it works, and the wine is finely knit, featuring crushed black cherry, mandarin orange peel, Herbes de Provence and anise notes.

Domaine Valentin Zusslin

Aligned with the same winemaking traditions it first established in 1691, Zusslin is located in the southern part of Alsace in Orschwir on the Bollenberg, Clos Liebenberg (a Zusslin monopole) and the hillsides of Pfingstberg Grand Cru.

Early to the Crémant game, the domain was also an early practitioner of biodynamics, having introduced this philosophy to viticulture in 1997. Says Valentin (whose name, perhaps, makes this an iconic sparkling wine for February 14): “We plant cover crops to encourage good insects and microbial life for the soil, encourage bees to pollinate the beneficial plants and we grow trees to attract the birds that eat the harmful bugs. This way of thinking carries through everything we do in the fields and in the winery.”

In addition, his wife Marie insists that their lifestyle goes far beyond a philosophy, and as evidence, she indicates the wall on the property that bears names of 13 generations of Zusslin winegrowers: “We represent not only history, but the circle of life.”

Domaine Valentin Zusslin, 2018 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Bollenberg’ Pinot Noir ($48)

Domaine Valentin Zusslin, 2018 Alsace lieu-dit ‘Bollenberg’ Pinot Noir ($48)

A biodynamic and 100% Pinot Noir from the long awaited 2018 vintage, the wine is from vines planted on the slopes of the Bollenberg lieu-dit, where the limestone equates to finesse and a salty undertone. The vineyard sits at the foot of the Vosges Mountains in one of the driest places in France with only about 15 inches of annual rainfall. Supple and silky, showing tones of cherry and minerality.

Notebook …

Winegrape Variety Over Geography?

Alsace has changed hands between Germany and France five times since 1681, the last time in 1945 when French finally became the official language. That said, the blats of the oompah band have not faded into the distant: Most of the vineyards have Germanic names and despite the official rule of thumb, the dialect spoken by Alsatians is a hybrid of French and German. Prior to the post World War I change of flags, Alsace was a main priority for the German authorities whose ultimate goal was Germanizing Alsace and its inhabitants, and wine was one of their first targets. During the war, occupied Alsace was prohibited from selling its wines using the region’s name. Winemakers were allowed to blend as they saw fit, even if doing so eliminated the distinctive characteristics that have come to be associated with Alsace. Riesling and Gewürztraminer—two of Alsace’s most significant grape varieties—were declared illegal.

Another upshot of this hybrid culture is that Germans have not historically be known to champion terroir. Certainly vineyards are of utmost importance to label classification and price, but sweetness levels and grape types are more the focus. As such, Alsace mentions the grape variety on the label, generally unheard-of in France. Terroir was never historically used to market wines in Alsace; the industry was organized to sell combinations of brands and varieties rather than shared vineyards.

Anne Trimbach (of the renowned Ribeauvillé domain) speaks of a recent change of heart: “When we leased a number of hectares from the convent, one of the conditions that the nuns put in place was that we would change our strategy and reference ‘Grand Cru’ on the label. The Family discussed it at length and decided that it was a natural progression. It just seemed like the right time to take that step, as I felt buyers and sommeliers were increasingly aware of and interested in terroir in Alsace.”

- - -

Posted on 2023.03.02 in France, Alsace | Read more...

A Portrait of The Wine as a Grape: The Pure Expression of Alsace’s Varietal Wines Domaine Schoffit in Six Grapes (6-Bottle Pack $189) + Alsace: Under Pressure (3-Bottle Pack $110)

If you’re ever called upon to distill the essence of Alsatian wine into a single, simplistic phrase, you might say: ‘German varietals done in French styles.’

Of course, like Alsace itself, nothing about wine is simple, and it’s a fact that Alsace produces some of the most complex and thought-provoking wines of any region on earth. But on the surface, the summation is absolutely accurate; the territory’s French/German connection is forged in history. These two European neighbors have struggled over possession of Alsace since 357 AD.

Located on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland, the region has switched hands between France and Germany four times since 1870, so it’s no surprise that the cultural underpinnings of the region have one foot in France and the other in Germany, and that their food and wine traditions follow the split-personality scheme. Culinary Alsace is an Alemannic and Frankish melting pot, with popular dishes including Baeckeoffe, Flammekueche, Choucroute, Cordon bleu and Vol-au-vent, while the seven grapes legally allowed for wine production in Alsace are the Germanic standbys—Pinot Blanc, Sylvaner, Riesling, Muscat, Pinot Gris, Gewürztraminer and the only red wine produced in Alsace, Pinot Noir. Alsatian alchemy transforms these familiar stand-by varietals into rich, balanced, often ethereal incarnations, from intensely aromatic and crispy dry versions, to the mellow, sweet Vendange Tardive (late harvest) and Sélection de Grains Nobles, to the sparkling Crémant d’Alsace—a slightly sparkling wine produced with the traditional Champagne method of secondary fermentation inside the bottle and representing a quarter of all Vins d’Alsace production.

So intense and beautiful are these wines that they frequently remind us of Cinderella: varietals that may elsewhere be plain and plebian, born to clean chimneys in other wine regions, but who don their full Princess Ball regalia in Alsace.

This week’s package includes six bottles from Alsace’s wunderkind Bernard Schoffit, whose reclamation of an abandoned vineyard in Rangen de Thann has put him in the crosshairs of wine experts across the globe. ($189)

Additionally, superb examples of lyrical Crémant d’Alsace are available in a three-bottle pack ($110).

Alsace: A Geologist’s Dream

An Alsace cliché: ‘Walk 100 feet in any direction and you’ll find a totally different soil composition.’

The terroir of Alsace is, in fact, a mosaic of diversity; soils underlying the vineyards are a tapestry ranging from the schist and granite of the higher elevations (extending into the Vosges Mountains) to the limestone and chalk of the lower slopes and to the clay and gravel of the valley floors. However, it is the unique, reddish-colored sandstone of Alsace—known as grès des Vosges—that may be most interesting. Vosges sandstone runs in a large, horizontal swath through the range just below the granite layer from which it is derived and atop a layer of coal. Grès des Vosges is hard, compact sandstone composed mainly of quartz and feldspar. Its pink-reddish color is due to the presence of decomposing iron (iron oxide, as also seen in red soils throughout the world) that occurred as a result of the slow cooling of large masses of magma as it hardened into granite.

Most of the wine-making villages in Alsace are built on four or five different formations in a juxtaposition of often-restrained parcels, providing a montage of uniquely abundant and diverse soils. These infinite variations are the very heart of the exceptional diversity found in the Vins d’Alsace.

Seven Grapes in Search of Terroir

As we’ve seen, geologic forces some 45 million years ago resulted in thousands of feet of downward drop of the broad rift valley through which the Rhine River now flows; the soils left by these tectonic machinations is a byzantine patchwork that can vary tremendously over a very short distance. These changes profoundly affect the suitability of each patch of ground for a particular grape variety.

Thus, Gewürztraminer is grown on the sandstone soils of the Kitterlé vineyard while profound Rieslings grown of the granitic soils of the Sommerberg. Refined Sylvaners grow on the limestone of the Zotzenberg vineyard, Pinot Blanc prefers rich, deep soil and Muscat fairs best on marl and sandstone. So well-matched is situation to varietal that unlike elsewhere in France, that by law and tradition, Alsace labels wine with grape variety first and by geographic location as an afterthought.

The Enigma of The Grand Crus

Among the assorted anomalies that makes Alsace unique in France is a somewhat ambivalent attitude toward its own Grand Crus. Although there are 51 of them, not every producer or even every Grand Cru is happy with the restrictive, creativity-squashing rules that bind them. For example, with very few exemptions, Alsace Grand Cru must be a white wine produced 100% from a single variety of the four ‘Noble’ grapes—Riesling, Gewürztraminer, Pinot Gris or Muscat, which may be Muscat Ottonel, Blanc à Petits Grains, and/or Rosé à Petits Grains variations. Alsace Grand Cru wines must be vintage dated, cannot be released until June 1 of the year following harvest and are required to be bottled in a traditional Flûte d’Alsace. Vendange Tardive (late harvest) and Sélection de Grains Nobles (botrytis-affected) wines must be hand-harvested and require an additional year of aging.

Generally located at altitudes between 650 and 1300 feet, where grades are often quite steep, Grand Crus benefit from distinguishing soils as well as exposures and micro-climates that promote slow, consistent grape maturation—a key factor in developing the finely expressed aromas of Alsace wines.

As noted, among the exceptions to the ‘100%’ rule is Altenberg de Bergheim, located in the hills above the commune of Bergheim in the Haut-Rhin. It is the only Alsace Grand Cru wine allowed to contain Pinot Noir, and blends must be 50-70% Riesling, 10-25% Pinot Gris, 10-25% Gewürztraminer and may contain up to 10% (combined) Chasselas, Muscat (à Petits Grains or Muscat Ottonnel), Pinot Noir, and/or Pinot Blanc. Kaefferkopf Grand Cru is also allowed to produce blends, using 60-80% Gewurztraminer and 10-40% Riesling; they may also include up to 30% Pinot Gris and up to 10% Muscat.

Domaine Schoffit

Alsace’s Reclaimed Treasures

As the southernmost Grand Cru, Rangen de Thanni is a fitting ‘ciao’ to Alsace; ‘ciao’, of course, can translate to either ‘hello’ or ‘goodbye’ depending on the direction you are heading. With Bernard Schoffit, it is high time the world gave him a hearty hello and never mind the rest; he is a star who has not yet supernovaed in the wine universe, and as a result, his gems are extremely affordable.

To call a man a ‘pioneer’ who cultivates wine country that has been famous for eight hundred years (vintage 1228 was described as ‘extremely good; so hot you could fry an egg in the sand’) may seem a stretch, but the spirit that impelled Bernard Schoffit to purchase 16 acres around Clos St. Théobold belongs to a frontiersman. Previously abandoned because the slopes were deemed too steep to work, the vines in question (in Rangen de Thann AOP) grew on a plot of soil that has been likened to Montrachet and Chambertin. And from this forbidding site, relying on extremely low yields, he is making extraordinary wine with each cépage.

In addition, Schoffit raises grapes in the lieu-dit Harth, an alluvial terroir close to the commercial area of Hussen in northern Colmar, and three acres in the granitic Grand Cru Sommerberg to the south of Katzenthal and to the north of Niedermorschwihr. In Harth, Schoffit tends 80 years old Chasselas vines, of which a few percent are replanted each year as an illustration of Schoffit’s long-term perspective.

Bernard and Alexandre Schoffit, photo courtesy of Savage Selection

Based near Colmar, Bernard took the winery over from his father Robert and his son Alexandre is now a co-owner. Demonstrating the estate’s commitment to sustainable agriculture Alexandre maintains, “All our vineyards are organic, and we also started to work biodynamic a few years ago. In order to show more transparency, I decided in 2016 to launch the official certification process, but for administrative reasons it was stretched over different years. The first wines officially labeled fully organic will be some cuvées of the 2019 vintage (Harth Riesling and Harth Pinot Gris for example), and the rest of the classic range will follow in the 2020 vintage. For the Grand Crus, it will be from the 2022 vintage. The official certification for biodynamic is in progress and we are still waiting to know from when we will be able to use it on the labels. But for now, Domaine Schoffit gives the assurance that we are both bio and biodynamic!”

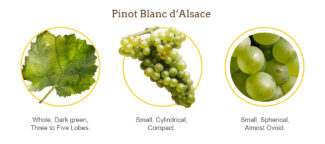

Pinot Blanc d’Alsace

‘Light, Supple and Spring-like’

Pinot Blanc is often thought of as understudy to Chardonnay (especially in Burgundy, where it is still permitted in many Grand Cru vineyards), but it takes on the diva’s role in Alsace. It is the region’s favorite mutant, the ‘white sheep’ of the Noir family since it is a genetic anomaly that originated as Pinot Noir, but with a smaller concentration of color-producing anthocyanins. Alsace puts the grape to work in the production of still, sparkling and sweet dessert wines, although it is frequently overshadowed by more popular Alsatian gems made from Gewürztraminer and Riesling.

Pinot Blanc d’Alsace frequently displays toasted almond aromas with hints of pie spice; nutmeg especially. On the palate they show a range of creamy applesauce flavors, and may display some light mineral characteristics, although these are generally muted by the oak treatment that Alsatian winemakers tend to favor.

•1• Domaine Schoffit ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2020 Alsace Pinot Blanc – Auxerrois ($20)

•1• Domaine Schoffit ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2020 Alsace Pinot Blanc – Auxerrois ($20)

Made from 50-year-old vines, the vinification starts with gentle pressing and clarification of cool must for 48 hours. The wine displays subtle notes of yellow plum with a pure-fruit edge translating to freshness on the nose. The assemblage includes some Auxerrois, which lends stone fruit flavors and a lucid lemon-ginger zing to the mid-palate while white plum notes follow through to a mineral-driven finish.

Chesselas d’Alsace

‘Light with Discreet Fruitiness”

The main grape in the German wine Edelzwicker, Chasselas is no longer widely planted in Alsace despite its productivity, although it’s a cornerstone varietal in its homeland, nearby Switzerland, where it is the second most-planted vine.

Under normal harvest conditions Chasselas produces somewhat bland, fruity wines that do not have much longevity in the bottle. But by keeping yields low and vines thirsty, it produces smaller berries with much more concentration—a hallmark of all fine Alsace wines.

•2• Domaine Schoffit ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2020 Alsace Chasselas ($25)

•2• Domaine Schoffit ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2020 Alsace Chasselas ($25)

100% Chasselas. From a two-acre parcel planted in 1935 on alluvial, gravel-filled soils of gravel in Colmar; entirely hand-harvested, fermented and aged in stainless steel tanks. The wine hints of fresh and corn husk in a delightfully dry nose and palate fresh with lemon peel and peach, with a subtle undertone of Bosc pear. The finish is classically dry finish with mouthwatering salinity.

Riesling d’Alsace

‘Elegant, Fresh and Delicately Aromatic’

With little space for argument, the statement can be made that Alsace produces some of the most terroir-reflective Rieslings on earth, echoing precisely the mix of granite, limestone, schist and sandstone on which they are grown. The wine is rarely oaked and only produced in off-dry versions labeled Vendange Tardive (late harvest) or Sélection de Grains Nobles (from grapes affected by botrytis). In general, it is the most prolific grape among Alsatian vineyards, accounting for 22% of planted acreage Average annual Riesling production is about 2.8 million cases by some 950 producers.

The wines are intensely linear, and have a distinctively complex acid structure and high concentration. Aromatic and expressive, they display intense aromas of citrus, peach, pear, white flowers and a steely minerality and are particularly well-suited to aging, where the fruit recedes and yields to aromas of beeswax, lanolin, butter, smoke, pine, honey, butterscotch, mushroom, lemon candy and especially, overtones of gasoline, which is more delectable than it sounds.

•3• Domaine Schoffit, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Rangen ‘Clos Saint-Théobald’ Riesling ($59)

•3• Domaine Schoffit, 2019 Alsace Grand Cru Rangen ‘Clos Saint-Théobald’ Riesling ($59)

The volcanic soils of Rangen, characterized by their low clay content, lie beneath one of the warmest plots in the region, a combination that generally pushes this Grand Cru to the top of the list. At 14.3% abv, it is precise and potent in comparison to a German Riesling, showing dried peach, lemon curd, fresh lime and Rangen’s classic, slightly resinous aromas of fresh rosemary.

Gewürztraminer d’Alsace

‘Intense, exuberant and Aromatic’

If ever a grape variety can be thought of as an ‘acquired taste’, it’s Gewürztraminer, whose unctuous, oily, often musky scent is (at least) easy to recognize. It is a white wine, although the grapes themselves are pink and impart a slight tint to the juice, making it a wine identifiable not only by bouquet, but by color alone.

Gewürz performs best on the heavier, clay soils of Alsace’s Haut-Rhin department, and can quite easily attain the sort of ripeness needed for the sensational late-harvest bottlings labelled Vendange Tardive and Sélection de Grains Nobles. That said, the variety ripens so fast it needs to be planted somewhere relatively cool if it is to develop any discernible perfume but must be harvested while acid levels remain high enough to balance sugars.

Picked judiciously, Alsace Gewürztraminer ‘sec’ is pungent, dry and powerful enough to accompany rich food, and reaches heights of complexity here unmatched anywhere else in the world.

•4• Domaine Schoffit ‘Cuvée Caroline’, 2019 Alsace ‘lieu-dit Harth’ Gewürztraminer ($26)

•4• Domaine Schoffit ‘Cuvée Caroline’, 2019 Alsace ‘lieu-dit Harth’ Gewürztraminer ($26)

A classically concentrated Alsatian Gewürz, with unctuous flavors of tropical fruit, honey, pear and lychee in front of a distinct smokiness. Lengthy, fresh, and a touch bitter on the finish, with top notes of orange pith.

Pinot Gris d’Alsace

‘Generous, Ample and Full Bodied’

Another mutation within the Pinot family, Pinot Gris is a sibling of Pinot Noir and Pinot Blanc, and perhaps among the most double-faced grapes on earth: It creates the light, crisp, often forgettable Pinot Grigios of northern Italy and (without undergoing any mutations whatsoever) becomes rich and unctuous in Alsace. Location, location, location… and restricted yields.

Most identifiable by ripe poached pear notes, in Alsace the grape also reveals a floral, flinty, smoky, spicy and honeyed profile, allowing winemakers revel in the possibilities.

“In the past, Grand Cru Alsace Pinot Gris was usually made in an off-dry or sweet style, but today, it is possible to make it in a dry style,” says Alsatian winemaker Samuel Tottoli. “For me, it is necessary to vinify it dry. Low yields from stony vineyards ensure the wine is concentrated, while prime sites with well-drained soils further promote ripening before too much sugar develops in the grapes.”

•5• Domaine Schoffit ‘Tradition’, 2019 Alsace ‘lieu-dit Harth’ Pinot Gris ($26)

•5• Domaine Schoffit ‘Tradition’, 2019 Alsace ‘lieu-dit Harth’ Pinot Gris ($26)

When the word ‘Tradition’ appears on a Schoffit label, expect a dry wine. When it reads ‘lieu-dit Harth’, it comes from a prized vineyard near Colmar and you expect a super ripe, full-bodied wine that amplifies the profile of the varietal. In this case, the pear notes that often define Pinot Gris are a symphony, with highlighted sections of bright acidity, high-toned cinnamon and gentle wood smoke. In the fourth and final movement, look for citrus, jasmine, melon and pineapple.

Pinot Noir d’Alsace

‘Full-bodied, Heady and Intensely Fruity’

Pinot Noir in Alsace—the only red wine grape permitted by AOP law—is a poster child for the upside of climate change. Once capable of producing only highly acidic, thin-bodied wine except in rare vintages, the slow creep of temperature increases throughout the region has seen a remarkable make-over for Burgundy’s pet red: Pinot Noir d’Alsace is currently producing rustic wines that showcase the varietal’s classic cherries, cranberries, strawberries and raspberries cloaked in supple, soft tannins. In the hands of top producers in particularly warm seasons, these wines are as earthy and complex as Cru Burgundy.

•6• Domaine Schoffit ‘Vieilles Vignes Vendange Entière’, 2018 Alsace Pinot Noir ($33)

•6• Domaine Schoffit ‘Vieilles Vignes Vendange Entière’, 2018 Alsace Pinot Noir ($33)

‘Vendange Entière’ refers to whole-cluster fermentation—a cellar technique intended to make a given wine more complex, weaving in spicy and herbal while adding candied and airy fruit and tannin structure, and also, to smooth out high acidity. In short, it is a method winemakers use to override anything lacking in a cool climate Pinot. Here, it works, and the wine is finely knit, featuring crushed black cherry, mandarin orange peel, Herbes de Provence and anise notes.

Crémant d’Alsace

Under Pressure

Alsace contains three individual AOPs: The general Alsace AOP to cover white, rosé and red wines; Alsace Grand Cru AOP for white wines from certain classified vineyards, and the newest kid on the block—Crémant d’Alsace AOP for sparkling wines—a designation made formally effective in1976. From this latter region comes 30 million bottles of sparkling wine per year, a staggering figure until you compare it to Champagne’s 300 million bottles.

As in the Grand Crus of Alsace, Crémant AOP is riddled with rules, some stricter than Champagne. Among them, allowed varieties are Auxerrois, Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Noir and Riesling, and unlike Champagne, Rosé may only be made from Pinot Noir. Additionally, the harvest must come grapes have to come from vines into its 3rd growing season and the wine may not be bottled for the second fermentation before January 1 of the year after the harvest. The wine must then spend at least 12 months ‘sur latte’ before disgorging. It is—like Champagne—required to be made via Méthode traditionnelle.

left to right … Jacky Barthelmé, Sébastien Mann and parents, Valentin Zusslin

The following superb examples of lyrical Crémant d’Alsace are available in a three-bottle pack for ($110).

Jacky Barthelmé (Domaine Albert Mann)

Wettolsheim is a hamlet a few miles west of Colmar, but it is still biggest wine village of the Haut Rhin by vineyard surface area. It is also the nexus of Domaine Albert Mann, the joint efforts of two big winemaker families, Mann and Barthelmé. The Manns have been winegrowers since the beginning of the 17th century and Barthelmés since 1654; today’s generation is led by brothers Maurice and Jacky Barthelmé and their wives, Marie-Claire and Marie-Thérèse.

The domain’s 50 acres are spread across eight communes where the soil structures are specifically suited to the style of wine produced, including silica to offer vivacity, clay to add mineral notes, limestone for richness and marl to preserve acidity. Among the family’s commitment to preserving the estate’s remarkable terroir are a vigorous replanting of old vines to maintain diversity, allowing grass to grow between every other row while a horse ploughs the rest, and the use of natural compost to encourage the formation of humus and to aid with the assimilation of minerals in the subsoil.

Say Marie-Thérèse Barthelmé: “Wine is the grape’s memory.”

•1• Domaine Albert Mann, 2019 Crémant d’Alsace ($36)

•1• Domaine Albert Mann, 2019 Crémant d’Alsace ($36)

Hand-harvested from Kientzheim and Wettolsheim, this blend of Pinot Blanc and Auxerrois shows lightly toasted brioche, tangerine and white cherry with a fine mousse and charming textures, fringed with meringue and jasmine-blossom tea.

Sébastien Mann (Domaine Mann)

After stints in Côte-Rôtie and Champagne, where he learned the value of biodynamics from Bertrand Gautherot, Sébastien Mann has been making wine at the family estate since 2009 after taking over for his father. He says, “I think that thanks to biodynamics, we have succeeded in bringing an additional element to our vines. My father made wines essentially linked to the earth; I have an even more holistic style, linked to the stars.”

Domaine Mann’s 32 acres were founded upon the theory that in order to produce terroir-driven wines with aging potential, legally allowable yields have to be cut in half. From the outset, the estate produced 35 cuvées, one for each parcel.

“The style of the wines changed very quickly when I came on board,” Sébastien maintains. “95% of the wines we produce now are dry. It was not an easy task, since Alsace is one of the warmest and driest regions in France. Grapes can easily ripen with a high sugar level. I don’t think my father could imagine that with biodynamics we would be able to achieve such a great evolution, achieving phenolic maturity while making dry wines.”

•2• Domaine Mann, 2018 Crémant d’Alsace Brut Nature ($35)

•2• Domaine Mann, 2018 Crémant d’Alsace Brut Nature ($35)

A blend of Auxerrois, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, bone dry with zero dosage, leading to the designation ‘Brut Nature.’ It spends 30 months on lees, leading to luxurious creaminess, a characteristic of Mann sparkling wines. Notes of Golden Delicious apple play on the nose with a hint of white pepper shimmering in the background.

Valentin Zusslin (Domaine Valentin Zusslin)

Aligned with the same winemaking traditions it first established in 1691, Zusslin is located in the southern part of Alsace in Orschwir on the Bollenberg, Clos Liebenberg (a Zusslin monopole) and the hillsides of Pfingstberg Grand Cru.

Early to the Crémant game, the domain was also an early practitioner of biodynamics, having introduced this philosophy to viticulture in 1997. Says Valentin (whose name, perhaps, makes this an iconic sparkling wine for February 14): “We plant cover crops to encourage good insects and microbial life for the soil, encourage bees to pollinate the beneficial plants and we grow trees to attract the birds that eat the harmful bugs. This way of thinking carries through everything we do in the fields and in the winery.”

In addition, his wife Marie insists that their lifestyle goes far beyond a philosophy, and as evidence, she indicates the wall on the property that bears names of 13 generations of Zusslin winegrowers: “We represent not only history, but the circle of life.”

•3• Domaine Valentin Zusslin, nv Crémant d’Alsace Rosé Brut Zero ‘Natural’ ($39)

•3• Domaine Valentin Zusslin, nv Crémant d’Alsace Rosé Brut Zero ‘Natural’ ($39)

Another perfectly dry Brut Zero, and since it is forbidden for Crémant producers to blend red and white grapes to make rosé, this one is 100% Bollenberg Pinot Noir, created and bottled without sulfites. It is an elegant saignée rosé, with red berry aromas on the nose, intense fruit-skin intensity and a striking mineral profile to the finish.

Vintage Journal

2020

The 2020 growing season began with an unusually warm spring, which saw both an early budburst and flowering. The summer quickly picked up steam, but little rain—extremely hot conditions made drought a serious issue in some vineyards, as the delicate nature of Alsace white grapes means they are particularly sensitive to heat stress. There was enough intermittent rainfall to prevent the grapes from becoming completely parched, although the high temperatures inevitably sped up the growing season prompting an early harvest. Picking began in early autumn during a heatwave, which meant pickers had to be careful grapes were brought in under suitably cool conditions. Overall, despite the problems with drought, the harvest produced grapes in good condition, with their essential aromatics and acidities preserved.

2019

Overall, the 2019 vintage in Alsace was very good. Chilly spells during the spring were accompanied by the typical seasonal frosts in April. Temperatures began to warm up in May and hot weather in June and July eliminated both rot and mildew. Rain fell in August relieving the vines from drought and the good conditions continued for the September harvest. These conditions are ideal for offering grapes to develop concentration and depth without suffering drought-related stress.

2018

The first half of 2018 was characterized by unusually high rainfall which allowed the soils to build important reserves for the upcoming summer months. Surprisingly, despite the heavy rains, flowering was not only successful but arrived earlier than normal. A warm, dry summer saw temperatures spike in July, making the few light rains that fell in August quite welcome. Although the grapes tended to ripen more quickly than normal, the harvest still occurred at a leisurely pace over two months. All the whites delivered impressively, particularly wines made from Gewürztraminer, Muscat, Pinot Blanc and Sylvaner. However, Pinot Gris generally stole the show with beautifully rich, aromatic wines. Riesling was perhaps the trickiest, less suited to the warmer temperatures, but October’s warm days and cool nights helped the grapes to ripen while retaining their acidity, creating superlative Vendanges Tardives.

Notebook …

The Sugar Question: Sec Means Sec

“We’re not in favor of the change, especially for Riesling,” says Emanuelle Gallis of leading Alsace cooperative Cave de Turckheim. “But in the end, it’s not a catastrophe. It’s only one word—just another rule on top of all the others.”

That word is ‘sec’, meaning ‘dry’—a word which Alsace producers have been obliged to carry on the label of their dry wines since the 2016 vintage. This is the Association of Alsace Producers’ interpretation of a European Union law stipulating that one of four levels of sweetness should be carried on labels: sec, demi-sec, moelleux and doux; the AVA was concerned that consumers were turning away from Alsace wines because they were afraid of buying an off-dry or sweet wine when they wanted a dry one. “This has become particularly clear in Parisian brasseries,” says AVA president Jérôme Bauer, “where Alsace Rieslings are getting rarer.”

As a result of the new rule, dry Alsace wines must be labeled ‘sec’ if they have maximum four grams of residual sugar per liter—an INAO rule that had previously applied to all other French wine regions beside Alsace. Although it seems like a logical decision, it has not been embraced willingly by all producers, some of whom feel it is misguided, as the default style of Alsace whites is mineral dryness rather than sweetness.

- - -

Posted on 2023.03.01 in Crémant d'Alsace, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Alsace | Read more...

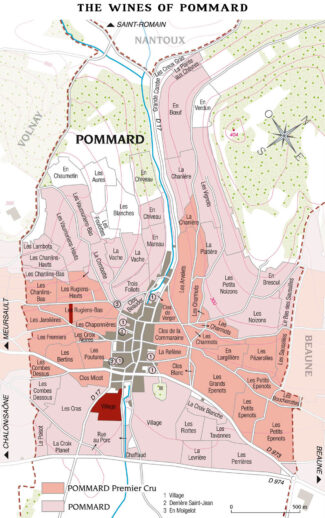

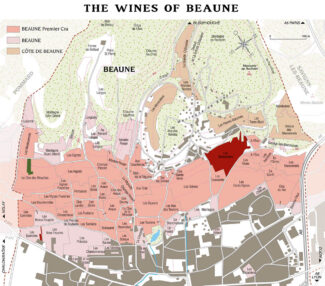

Clarification of The Possibilities of Pinot Noir in Burgundy. Domaine du Pavillon Articulates The Case Throughout Côte de Beaune’s Appellations with Vintage 2020

So well does Pinot Noir align with its terroir that it is no stretch to claim that the Burgundian earth itself was mute before the first plantings. But the truth is, fickle Pinot Noir has found its spiritual home here only through centuries of trial, error and site selection along with the endless pruning required to allow the grape its most expressive stage. In truth, there are many grapes that are easier to grow in Burgundy, are subject to fewer diseases, are easier to maintain and which produce a more consistent and copious yield. The problem? They aren’t Pinot Noir.

Domaine du Pavillon, one of the Albert Bichot constellations of excellent estates, has produced a variety of Côte de Beaune Pinot-based wines that articulate not only the heritage that has permitted this red wine grape to maintain a crowning place in the varietal hierarchy for centuries, but points to the stylistic changes that might be inevitable as part of the future new normal.

Throughout Burgundy, grapes have been regularly gaining ripeness and palate-sweetness unheard of even 20 years ago, while green, unpleasant tannins that refuse to soften or ripen with age are nearly a thing of the past. For all the horror stories (and none should be downplayed, of course) climate change has had an odd effect in Burgundy. Contemporary wines may be more seductive and charming when young, but are also likely to age well, as these outstanding selections for Domaine du Pavillon prove.

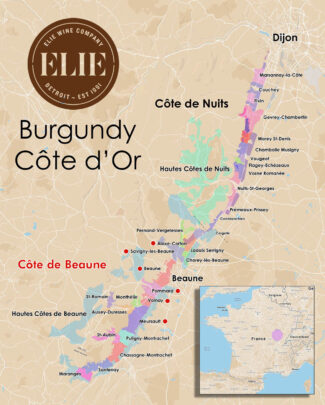

Burgundy: Land of Climats

Nowhere has an obsession with the minutia that connects wine to earth been pushed as far (and in such an elaborate manner) as in Burgundy. And nobody else has coined a term that more adequately describes this compartmentalized vineyard structure: ‘Climat.’ Carefully defined for centuries, and having remained virtually unchanged to the current day, a ‘climat’ is a parcel of vines which has its own name, its own history, its unique taste and place in the lexicon of wines. More than a thousand of them are inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

This is not to give a lower profile to the hundreds of communes and villages throughout Burgundy that also place a premium on self-expression. One of the great joys of the Burgundian experience is to explore each appellation and learn to distinguish identifying characteristics, from the most broad to the most nuanced.

Pinotism Reigns

For all the drawbacks inherent in the work-intensive, thin-skinned, low-yielding Pinot Noir variety, the end result is a wine that announces its place of origin louder than nearly any other. When coddled and protected, Pinot responds by mirroring the subsoil in which it is rooted, the slope of the land as it drains and the absorption of sunlight—in short, its microclimate. Referred to as ‘an infinite sensory experience’, Pinot Noir offers a wide variety of aromas when young, from fresh berries to spicy pepper and cinnamon, often underscored with coffee and smoky notes. Over time, the fresh fruit flavors will transform into mature notes of jam or kirsch, and the wine will develop exquisite aromas of wild mushroom or truffle accompanied by feral notes like leather or fur.

As an interesting historical side note, following the Black Plague (1349) many neglected Pinot vineyards were replanted to Gamay, which was not only more disease resistant, but produced more wine. The re-crowning of Pinot did not happen for more than a century (and over the objections of wine merchants who preferred the easy profits generated by copious and inexpensive Gamay); it required edicts from noblemen, including Duke Philippe le Hardi, who declared that Gamay was ‘most harmful to every human creature to such an extent that those who use it are subject to serious illnesses.’

Vintage 2020: Voluptuous and Structured

François Labet, a négociant whose family has lived in Beaune for 300 years, summarizes the 2020 vintage like this: “An intellectually-challenging vintage; the reds in particular defy easy categorization because the impact of that season varied considerably by terroir. Producers had key decisions to make, especially when to pick and that significantly affected both the style and quality of the resulting wines.

And this is because the most notable feature of this vintage was its early and rapid harvest: Many domains began picking the week of August 17th and while August harvests have been frequent in the 21st century (there were none in the prior century), this was for many domains the first time they had not only started, but completed a harvest before the end of August.

The resulting wines (particularly from earlier harvests where sugars were high and acids intact) are remarkable, both for whites and reds. The season was hot and dry, but water tables were healthy from the mild and wet preceding winter.

Beaune was particularly fortunate and Chef de Cave Frédéric Weber (Bouchard Père et Fils) describes 2020 as a concentrated and strong vintage: “It reminds me of 2016 for its vibrancy and energy; the wines are voluptuous and structured. A great vintage for the future, like the ‘18s.”

Vintage 2019: Concentrated and Vibrant

Of the bullseye vintage of 2019, Dimitri Bazas of Maison Champy in Beaune, says, “If you offer me a contract for 30 years and it promises that every year will be like 2019, I will say, where do I sign?”

In the season before the pandemic, a new phenomenon was beginning to take hold in Burgundy and growers were baffled: The 2019 vintage, largely from a drought year, showed previously unseen levels of both ripeness and acidity, producing a baffling combination of searing freshness, perfect ripeness and crystalline purity. After a blustery February and a wet March, well-forecasted frost hit in April, but after that, things heated up and stayed blisteringly hot through the beginning of September, when it cooled down and allowed the grapes on the vine to maintain good acids.

Côte de Beaune’s Benjamin Leroux maintains, “2019 is a great vintage, with quality to be found across the region and at every level. There are, naturally, different styles of wine, and some growers and areas have been more successful than others, but there should be something to appeal to all budgets and palates. In an uncertain world, the ’19 vintage offers reassurance: you can buy it with confidence.”

Domaine du Pavillon

The Essence of Côte de Beaune

Located south of Pommard, the Côte de Beaune’s Domaine du Pavillon is under the vinous umbrella of the Bichot family, who settled in Burgundy in 1350. Albéric Bichot took over management in 1996, and although he fully respects traditions, he remains focused on the future, comparing himself to the ‘conductor of an orchestra, proud to bring people and their talents together over a common project.’

Among those common projects is Domaine du Pavillon, whose 37 acres of vines include just under ten acres of Bichot’s Pommard monopole ‘Clos des Ursulines’.

Matthieu Mangenot

Meanwhile, among the talented people he has brought together is head winemaker Matthieu Mangenot who brings to Beaune a wealth of experience from estates in South Africa, Lebanon and Bordeaux. After his first experience in the Mâconnais/Beaujolais region, he joined Albert Bichot in 2007 as manager of Domaine Long-Depaquit in Chablis. His dual training as an agronomist and an oenologist allows him a comprehensive approach to winemaking, from vineyard management to bottling. His knowledge of soil formations and his pragmatic, transversal approach benefit the development of the House’s productions and pair well with its concern for authenticity and sustainability. “The wines of the Pavillon will bear the certified ‘organic wine’ label starting with vintage 2018,” he promises.

Viticulture is handled by Christophe Chauvel, assisted by Dominique Bon. Chauvel arrived in Burgundy in 1982 to study at Beaune’s viticultural secondary school, and after gaining experience under Sommelier Jean-Luc Pouteau at the restaurant Pavillon Elysée Lenôtre in Paris, he decided to go back to school to follow a 4-year winemaking program in Bordeaux. He joined the Albert Bichot estates in 1999.

Christophe Chauvel, left, Dominique Bon, right

Dominique Bon became interested in viticulture as a young boy. After 3 years of studies at Beaune’s viticultural secondary school, he was made manager at an estate in Meursault, in charge of clients’ vines (and vinification) for 13 years. On the side, he took over a small, six-acre estate which he still looks after. He joined Albert Bichot in 2000 as vineyard manager at Domaine du Pavillon where his knowledge of vines and specificities of the local terroirs are precious assets.

Work In The Vineyard

The twin motivators of respect for nature and respect for the planet are the cornerstone of Domaine du Pavillon’s approach to the craft. Sustainable viticulture is the watchword, based on observation, prevention and paying attention to the complex balances found in nature. Pavillon soil is maintained responsibly, judiciously ploughed and fertilized using only organic matter. In the field, hands-on labor boosts the plants’ natural defenses and dedicated teams know every nuance of the terroir perfectly and remain attentive to the development of the vines as they grow.

At The Winery and In The Cellar

‘As little intervention as possible’ animates Pavillon’s vinification process in each of Burgundy’s major viticultural regions from which they pull their grapes. The wines are always transferred from vinification vats or barrels to the cellars by gravity—the gentlest, most earth-friendly method. There it is allowed to mature in casks for 12 to 18 months in barrels, some new, some used. It is during this key period, when time and expertise come together, that wines first begin to reveal their personality and hint at their potential. Depending on the vintage, combinations of oak from different origins (Tronçais, Allier, etc.) and of varying degrees of toast are used to impart discrete yet complex nuance to the finished product.

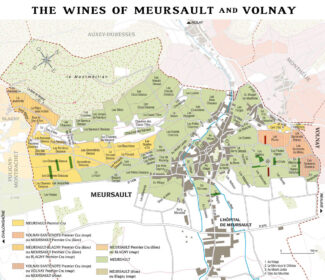

Meursault

There’s a rumor that Meursault’s name (derived from the Roman ‘muris saltus’, or mouse-leap) is meant to measure the distance between Pinot Noir acres and Chardonnay acres within the appellation. Alas, it’s an apocryphal tale—it actually refers to the Ruisseau des Cloux stream, which the centurions were able to easily get across.

Sitting at the entrance to the Saint-Romain valley—a gap in the Côte d’Or—the commune of Meursault stretches for three miles from north to south, making it about twice as large as Puligny. Most of the vineyards are located on the slopes of the Côte d’Or escarpment and are blessed with classic Burgundian limestone and marl soils. The vines are planted in a variety of orientations in the local hillsides, due south through due east, and such differences become one of many contributing factor to the variation of styles in Meursault wines.

Meursault contains 714 acres of Village-level vineyards and 259 acres of Premier Cru sites; more than 200,000 cases of white wine are produced per year, plus around 4000 cases of red wine.

Domaine du Pavillon, 2020 Meursault ($55) Red

Domaine du Pavillon, 2020 Meursault ($55) Red

From a 0.8 acre site of 40 year old vines located just north of the village of Meursault, where exposure is east/southeast and the soil is marly clay. Hand-picked, the Pinot Noir is crushed, then put in temperature-controlled conical oak vats for four weeks and aged in oak for 14 -16 months, 20% new. The wine displays a delicate nose of crushed cherries and rose petals with a touch of coffee and elegant tannins on the finish. 2000 bottles made.

Domaine du Pavillon, 2020 Meursault ($99) White

Domaine du Pavillon, 2020 Meursault ($99) White

Drawn from 5 plots totaling 5.6 acres of 30-year-old vines grown on white marly limestone and clay. The wine is vatted in 30% new oak, then aged in oak for another 12 – 15 months. It reveals a nose of yellow peach, vanilla and toasted almond, round in the mouth with elegance and length and a crisp, mineral finish. 15,000 bottles made.

Domaine du Pavillon, 2020 Meursault Premier Cru Les Charmes ($153) White

Domaine du Pavillon, 2020 Meursault Premier Cru Les Charmes ($153) White

From a 2.89 acre plot, mostly from the upper portion of the Les Charmes lieu-dit called ‘Charmes du Dessus.’ Exposure is east/southeast on gentle slope at an average elevation of 800 feet. The soil is calcareous clay and the vines are around thirty years old. The juice is vatted in oak, about 60% new, then aged in oak for about 15 months, 25% new. The wine features aromas of candied lemon, toasted almond, white flowers and freshly baked bread; palate is smooth and velvety without heaviness and mirrors the bouquet’s aromas. 7,500 bottles made.

Domaine du Pavillon, 2019 Meursault Premier Cru Les Charmes ($153) White

Domaine du Pavillon, 2019 Meursault Premier Cru Les Charmes ($153) White

Les Charmes is among a cluster of top climats, with Genevrières on the northern border and Perrières above it on the slopes. Charmes Premier Cru wines tend to be vibrant and honeyed with rich, nutty characters and floral overtones. A large and diverse area, this particular cuvée is a blend of primarily Dessus (the upper part of the vineyard) and a lesser amount of the lower portion, called Dessous. The wine is laced with peach, lemon cake and sweet spice aromas along with acacia and spice and bright acidity adding lift. 7,500 bottles made.

Volnay