Burgundy’s Rustic Wine Belt New Found Opportunities: Changing Climate Advantages Lesser Known Regions; Ambitious Producers Elevate The Wines To New Heights (Auxey-Duresses, 6-Bottle Pack $399) (Monthélie, 5-Bottle Pack $279) (Saint-Romain, 3-Bottle Pack $159)

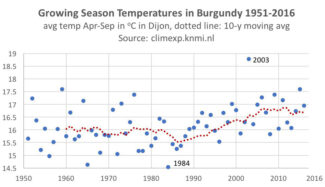

Climate change gets a lot of ink in this newsletter, and there’s a reason for it: Consistently elevated temperatures and unpredictably violent weather is having a profound effect on some of the world’s most celebrated wine regions, and the new normal is becoming ‘adapt or fade away.’

This week, we will take a peek behind the Doppler radar curtain to see how regions once considered marginal by grape-growing standards are finding new opportunities in the shifting panoply of weather patterns and rising, rung by rung, up the ladder of excellence.

The Impact of Climate Change on Burgundy: Upending The Status Quo

Dateline Burgundy, 2022: “As a fourth consecutive growing season is marred by extreme heat and frost, historical and predictive data suggests we can expect the same this year, too.”

2022 came close to fulfilling this prophecy, with a salvaging rain in June. 2023, just drawing to a close, mirrored these conditions, with excessive heat and a bit more rain. In general, however, even with adequate rainfall, consistently above-average daytime temperatures have become a feature in modern Burgundian vineyards. The effect is felt across the entire European continent, of course, and everywhere that grape vines thrive, but Burgundy’s Achilles heel is that it has placed the bulk of its eggs in two baskets: Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Pinot, being thin-skinned, suffers from too much direct sunlight; alternately, excessive rain may encourage the multiple mildews that Pinot’s flesh is heir to. Chardonnay, while better suited to the heat, may be devastated by late or severe frosts, which are appearing with greater frequency under the changing climate.

And now, the flip side of the coin: Burgundy, long beholden to classification, has begun to see once-marginal sites producing better wines, and it has been suggested that the entire system be revamped. Naturally, fundamentalists express disdain for the step taken by wine boards in Bordeaux: Approving the inclusion of new varieties better able to withstand spring frosts and dog-days heat. Previously neglected or abandoned grapes such as Aubin, Roublot, Sacy, Melon, César and Tressot are among the Burgundian candidates, some of which are already planted in small amounts around the region.

Although Burgundy’s reputation is built upon tradition, with many of the established estates having dominated the scene for centuries, the danger of ignoring the shifting tides of climate is the greatest threat of all. Without a profound re-imagining of habits built up through generations of winemaking, classified Burgundy wine may become what we consider to be unthinkable: Ordinary.

Solar Vintages Roll: 2018, 2019 And 2020

On average, Burgundy sees 1900 hours of sunshine per year; glance at a diagram and you’ll see a neat curve that peaks in July with around 258 sunlit hours and then drops off precipitously for the rest of the year. Vintages that bring considerably more sun hours are referred to as ‘solar’ vintages. 2018, 2019 and 2020 go down as a triumvirate of such vintages.

Even before en primeur orders were placed, 2018 was being hailed as a vintage that resembled the ideal conditions of 1947. Hopes ran high that the atypical ripeness and plushness of the wines might represent a ‘new normal’ in Burgundy. Part of the success of the vintage, in particular for the whites (which show gobs of energetic freshness and alluring fruit) was a particularly wet preceding winter that raised water tables high enough that the ensuing drought was handled easily, especially by more mature vines. The factor most crucial to success was determining harvest dates—pick too soon, and the fruit will not be phenologically ripe; too late, the grapes will flab out and lose acidity.

2019 followed with another bullseye. Dimitri Bazas, director of Maison Champy in Beaune, said, “If you offer me a contract for 30 years and it promises me that every year will be like 2019, then I would say, where do I sign?” The ideal ripeness and special personality of the vintage lies in a growing season that was the third-warmest year of the last century. Two short blasts of extreme heat at the end of June and the end of July were offset by enough rain to prevent serious drought stress to the vines.

2020 cranked up the above conditions another notch; it became a vintage in which one said ‘despite’ rather than ‘because of.’ Even the most experienced taster doubted that the heat and dryness, forcing harvest in August, could possibly produce such a fresh and joyous style. This was a vintage that tested Burgundian vignerons to the max; adaptability and careful attention to the vagaries of nature was key. In 2019, wine from high on the slopes of the Côte d’Or showed the highest levels of dry extract and salty minerality, providing balance for the ripe fruit, while in 2020, the extract combined with fresh acidity to make the wine truly electric.

(6-Bottle Pack $399)

Auxey-Duresses

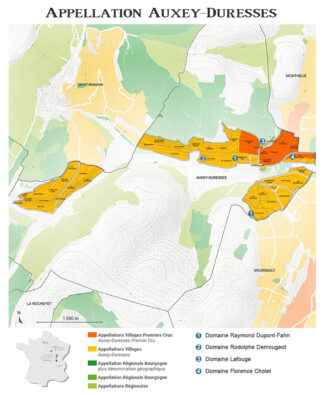

There was a time when the wines of Auxey-Duresses were sold under false premises—the reds were named Volnay and the whites, Meursault. In fact, experts could easily tell the difference. Yet, the differences have begun to evaporate as a new generation of winemakers in the appellation, coupled with a changing climate, has realized that Auxey-Duresses grapes may have the breeding to rival their hallowed neighbors without the need of fraud.

The first obstacle they had to overcome was geography. Unlike Meursault and Volnay, Auxey-Duresses vines cling to a variety of high slopes and have traditionally produced a hard red wine that is frequently sold to négociants for Bourgogne Rouge blends. But with patience, these same grapes, when bottled at estates within the appellation, improve immeasurably and become silken gems that may rival nearby powerhouses at a fraction of the cost.

Likewise Auxey-Duresses whites that may initially produce the hazelnut whiffs familiar to fans of Meursault, are beginning to produce wines of increasing depth that improve exponentially in the cellar. The warmer weather has been a godsend to intrepid vignerons who have raised the value of Auxey-Duresses far beyond its current price tag.

Domaine Raymond Dupont-Fahn

Raymond Dupont-Fahn is a fifth generation winemaker who began working in the family business as a child. After earning a Bac d’Oenologie diploma, he took over 12 acres of vines from his father, including plots in Meursault, Puligny-Montrachet and Auxey-Duresses. The domain is located in the village of Tailly in Meursault. As a winemaker, Raymond has cut down on the use of new oak (from the 40% used by his father to just 10%), with barrels that are no newer than three years. He uses no pesticides in the vineyards, aiming to be as sustainable as he can, and harvests slightly earlier than his neighbors to produce wines with better acidity and lower alcohol.

Raymond Dupont-Fahn

“My secret to success is no secret at all,” he says. “I work hard in the vineyard, without pesticides/herbicides and keep a meticulously clean cellar. I am not a fan of new oak or racking; I only stir to avoid overt reduction.”

He also tends to harvest right as the fruit reaches peak maturity, avoiding over-ripeness in a quest for a bright, pure and transparent style of Chardonnay.

Domaine Raymond Dupont-Fahn, 2019 Auxey-Duresses ‘Derrière le Four’ ($50)

Domaine Raymond Dupont-Fahn, 2019 Auxey-Duresses ‘Derrière le Four’ ($50)

Meaning ‘behind the oven’, ‘Derrière le Four’ is heavily scented with crushed raspberry, wild strawberry, and pomegranate along with hints of white pepper and herbs. It is an ideal Pinot Noir with delicate floral aromas to offset the tension between crunchy acidity and refined tannins.

Domaine Raymond Dupont-Fahn, 2018 Auxey-Duresses ‘Derrière le Four’ ($50)

Domaine Raymond Dupont-Fahn, 2018 Auxey-Duresses ‘Derrière le Four’ ($50)

The 2018 incarnation of ‘Behind the Oven’ with an extra year under its belt. Same profile as above with a tighter lens focused on this label’s potential.

Domaine Raymond Dupont-Fahn, 2019 Auxey-Duresses ‘Les Vireux’ Blanc ($55)

Domaine Raymond Dupont-Fahn, 2019 Auxey-Duresses ‘Les Vireux’ Blanc ($55)

‘Vireux’ might be directly translated as ‘noxious’ but here comes from ‘virer’, meaning ‘change’, as in the expression ‘virer de tout vent’—to be as changeable as the wind. The vineyard is located five hundred feet above the Meursault ‘Les Clous’ with northeast exposure; the wine shows lithe notes of crisp apple braced by a minerality that approaches salinity.

Domaine Rodolphe Demougeot

No one has summarized the trajectory of excellence in winemaking more succinctly than Rodolphe Demougeot: “One first needs to learn to be a good farmer, and only then learn to improve performance in the cellar.”

He further explains that in order to move away from the chemical farming used at the family estate he took over in 1992, he had to deprogram first himself and then the vineyards, an undertaking of several years. In the meantime, his interest in the inexplicable but observable energies of the cosmos and its influence on grapes and wine came to be central to his decision making: “The moon is my compass for the timing of processes during growing, farming, picking, racking, and bottling,” he says.

Rodolphe Demougeot

He plows most of his twenty acres by tractor, but in his top sites, like the Pommard, Premier Cru Les Charmots, he works with a horse. His cluster selection is made early in the season to concentrate the energy of the vines to fewer clusters through the fruiting season.

He describes his holdings like this: “We are principally between Meursault and Pommard, with only a single Premier Cru site in Pommard (Les Charmots) and many favorable village parcels between the two. In Meursault, all three parcels are on the south end of the appellation in fabulous spots above and below the great Premier Crus, Perrières, Genevrières, and Charmes. I have a small collection in Beaune, both red and white, as well as a village and Premier Cru in Savigny-lès-Beaune. Additionally, I work sites in Auxey-Duresses and Monthélie, fine and savory wines for those moments you need a stroll through the wet forest and all of its lovely fresh smells.”

Domaine Rodolphe Demougeot, 2015 Auxey-Duresses ‘Les Clous’ ($79)

Domaine Rodolphe Demougeot, 2015 Auxey-Duresses ‘Les Clous’ ($79)

‘Les Clous’ comes from Demougeot’s single acre of Pinot Noir planted in a direct south exposition—perfect for this sometimes cooler to the west of Meursault and between Monthélie and Saint-Romain. It does not receive much rain, and other than hail, it is a lieu-dit with a bright future in the face of climate change. The wine is aged in 85% French oak barrels with between one and six vintages of use for 14-16 months, resulting in a dynamic blend of ripe red fruit and integrated and elegant tannins.

Domaine Lafouge

Gilles Lafouge’s recipe for success can be broken down into three rudiments: Old vines, properly cultivated soils and classical winemaking techniques: “That these wines age beautifully, I can personally testify, having enjoyed a lovely 1969 Auxey-Duresses Premier Cru La Chapelle last summer—an unexpected but happy encounter on a local wine list,” says William Kelley of Robert Parker’s Wine Advocate.

Gilles Lafouge

The family’s estate, whose history in the area traces back to 1670, covers 25 acres in Auxey-Duresses, including plots in Premier Cru Climats du Val, La Chapelle, Les Duresses and Les Ecussaux.

In 1986, after wine school and national service, Gilles came back to work with his father, Jean and initiated a small revolution: Estate-bottling. The next generation is already heavily involved rather than simply waiting in the wings; Maxime Lafouge will represent the new vintage of winemakers who may indeed launch his own revolution.

Domaine Lafouge, 2016 Auxey-Duresses Premier Cru La Chapelle ($87)

Domaine Lafouge, 2016 Auxey-Duresses Premier Cru La Chapelle ($87)

‘La Chapelle’ is a climat within Les Breterins and Reugne on the steep slope of la Montagne de Bourdon, facing south/southeast. The vines are well-placed in mid-slope and are around sixty years old, making it the most generous of the three Lafouge Premier Crus. The soils are partially marnes blanches, contributing to the supple style—a classically proportioned blend of black cherries, a touch of cocoa powder, lovely soil tones, currant leaf, bonfire smoke and cedar.

Domaine Florence Cholet

Domaine Florence Cholet is an estate formed by Florence’s father Christian in 1976 (as Domaine Christian Cholet-Pelletier) who was joined in 1982 by his wife Anne. Located in the tiny village of Corcelles-les-Arts east of Puligny Montrachet and directly across from Meursault, the 18 acres of marl and limestone are planted to 75% Chardonnay and 25% Pinot Noir; vines range from 25 to 75 years in age and the estate bottles about 1400 cases per year.

Florence Cholet

Having gained work experience across France (Chapoutier), the United States (Walla Walla, Washington) and Australia, their daughter Florence studied biology and biochemistry at the University of Burgundy in Dijon where she earned a license in viticulture and a Master’s degree in oenology. In 2019, she returned to Corcelles-les-Arts to take over the estate from her parents, renaming it Domaine Florence Cholet. Among the innovations she brings to the domain is a policy against herbicides and pesticides; she ploughs by horse and allows natural fermentation on native yeasts. New oak is used sparingly at a maximum of 25% and wines are bottled using only a minimum of filtration.

Domaine Florence Cholet, 2020 Auxey-Duresses Premier Cru Les Ecussaux ($71)

Domaine Florence Cholet, 2020 Auxey-Duresses Premier Cru Les Ecussaux ($71)

Les Ecussaux is a Premier Cru vineyard on the Montagne du Bourdon, just to the east of the Auxey-Duresses village, between the roads to Beaune and to Meursault, whose junction forms its most westerly point. To the north lie the Premier Crus Les Duresses and Bas des Duresses. The wine displays firm tannins, crisp blackberry and mulberry, a touch of white pepper and a fleshy finish.

Domaine Florence Cholet, 2020 Auxey-Duresses ($61)

Domaine Florence Cholet, 2020 Auxey-Duresses ($61)

From 60-year-old vines grown between Meursault and Monthélie; Cholet’s penchant for gentle pressing and prolonged fermentation makes this a modern-style Burgundy filled with freshness and perfume. On the palate, there is cranberry crunch with wild strawberries and a touch of dried herb.

(3-Bottle Pack $159)

Saint-Romain

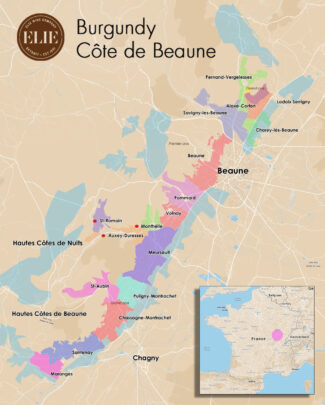

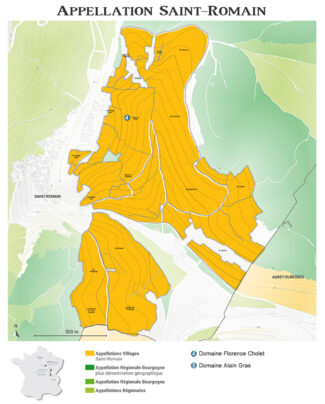

Saint-Romain is a village of 200 inhabitants nestling within a valley behind Auxey-Duresses and surrounded by steep cliffs. Neither the population nor the wine trade ever really recovered from the phylloxera blight of the 19th century, and today, only about 7% of the land is under vine. Like Chorey-lès-Beaune, Saint-Romain has no Grand or Premier Cru sites.

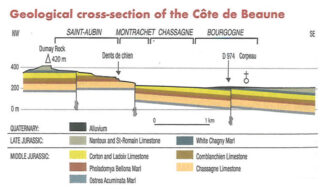

The village is divided in two parts, Saint-Romain-le-Haut and Saint-Romain-le-Bas, one on top of the cliffs and one below, with the bulk of the vineyards in the lower section. It is, nonetheless, a geologist’s Valhalla: Saint-Romain sits on the lias (the earliest period of the Jurassic) and the blend of limestones and marls includes patches of clay. The vines face south/southeast and north/northeast at altitudes varying from 900 to nearly 1300 feet.

Saint-Romain has always been an appellation that needed warm weather to thrive; it is simply too cold at these elevations to produce stellar wines in normal years. As such, they represent wines to seek out in solar vintages like 2018, 2019 and 2020.

Domaine Alain Gras

Established in 1979, Alain Gras refers to his domain as ‘young’, and considering that Saint-Romain has been occupied for more than 6000 years, there may be truth to that. His vines spread over 30 acres in Saint-Romain, Meursault, and Auxey-Duresses.

Alain Gras

Gras has found himself as a true ambassador of the Saint-Romain appellation: From a lineage of Burgundy vignerons that dates back five generations, he settled in Saint-Romain with his wife Nathalie and from the outset, their firm mission was to promote the appellation’s value. Joined by his son Arthur, Gras has advanced that value by his passion for rational viticulture and traditional vinification.

Locally acknowledged as Saint-Romain’s pre-eminent vigneron, Alain credits luck as much as talent: “My vineyards are wonderfully sited with a greater proportion of limestone than any other commune in Burgundy. It has also benefited greatly from recent climate change, meaning that sites that were previously overly cool due to their high altitude are now routinely achieving full ripeness and physiological maturity.”

Domaine Alain Gras, 2019 Saint-Romain Rouge ($54)

Domaine Alain Gras, 2019 Saint-Romain Rouge ($54)

Pure Pinot from vines averaging 35 years old; the bunches are 100% de-stemmed, fermented on the skins for 12 to 15 days with daily pump-overs, then aged in 15% new oak for 12 months. The wine shows black-cherry on the nose with notes of licorice and cinnamon in the background, creating an unpretentious profile with a bright floral finish.

Domaine Alain Gras, 2019 Saint-Romain Blanc ($53)

Domaine Alain Gras, 2019 Saint-Romain Blanc ($53)

From a clay-limestone vineyard where vines—treated with lutte raisonnée—average 40 years old. Green harvesting is practiced and all grapes are hand-harvested; 20% to 30% of the grapes are destemmed before pressing and fermentation takes place in barrels, following which the wine is aged in oak, including 20% new barrels and bottled after 12 months ageing. The wine shows hazelnuts, toasted bread and vanilla, whose delicate wood notes serve only as a background.

(5-Bottle Pack $279)

Monthélie

Author Pierre Poupon describes Monthélie as being “…prettily nestled into the curve of the hillside like the head of Saint John against the shoulder of Jesus. Monthélie resembles a village in Tuscany.”

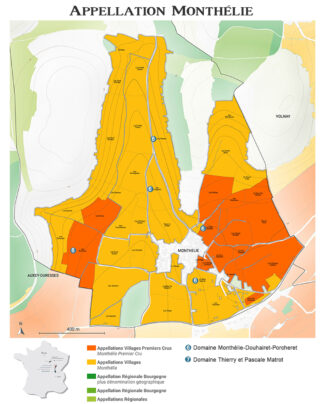

The appellation is home to 15 Premier Cru climats concentrated in one area to the east of the village, bordering the more prestigious vineyards of Volnay. A rose is a rose, but not all Premier Cru sites are created equal, and traditionally, those of Monthélie are not considered among Burgundy’s finest. Classic Monthélie wines are similar to those of neighboring Volnay (the villages are only a mile apart) but are not quite as full flavored or elegant, but they are generally considered to be superior to the red wines of Auxey-Duresses, also just a mile away in the other direction. Again, these are ideal terroirs to stir in a little extra warmth via global warming and follow the improvements with a corkscrew and glass.

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret

The triumvirate of names each has its own special significance to the estate. Named first for the 300-year-old Southern Burgundy village in which it is located, Monthelie-Douhairet was run by the Douhairet family for many years. In the early 1970s, the two sisters Armande and Charlotte Douhairet inherited the vines and decided to separate; Armande fought to keep her share while Charlotte sold hers. Then, in 1989, Madame Douhairet asked renowned winemaker André Porcheret to take charge and subsequently, added his name to the domain.

Cataldina Lippo and husband Vincent Monfort

André Porcheret has been one of the great figures in Beaune; prior to overseeing Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet he was the cellar manager at the Hospices de Beaune, then worked for Lalou Bize Leroy to make wines at the newly created Domaine Leroy—whereupon, he returned to the Hospices de Beaune for another five year stint. Today, with his granddaughter Cataldina Lippo, he produces wines on M-D-P’s fifteen acres that are classic, elegant and true to the terroirs of Pommard, Volnay, Meursault and Monthélie.

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret ‘Cuvée Miss Armande’, 2019 Monthélie ($43)

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret ‘Cuvée Miss Armande’, 2019 Monthélie ($43)

Armande Douhairet, known universally as ‘Miss Armande’, passed away in 2004, and to her memory, this cuvée is dedicated. The elevation of the vineyards, lieux-dits Les Plantes and Les Longènes, is obvious in the brightness of the red fruit, evoking pie cherries, orange rind and raw cocoa. The texture is satiny and succulent, with a core of richness framed by lively acids and powdery tannins.

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret, Monthélie ‘Clos du Meix Garnier’ Monopole ($47)

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret, Monthélie ‘Clos du Meix Garnier’ Monopole ($47)

‘Clos du Meix Garnier’ is a vineyard entirely owned by the estate—making it a monopole. From these three acres, about 8000 bottles are produced annually; the grapes are 100% de-stemmed and treated to gentle, old school fermentation and maceration before being aged for 18 months in barrels (10% new). Aromas of blood orange, raspberries and plums introduce a satiny wine with tangy acids and chalky tannins.

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret, 2019 Monthélie Premier Cru Les Duresses ($69)

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret, 2019 Monthélie Premier Cru Les Duresses ($69)

The 16 acres of Les Duresses is the only Premier Cru vineyard on the western side of Monthélie between Volnay and Meursault. Les Duresses is planted to 82% Pinot Noir, although there is some Chardonnay on the upper slope. Soils are pebbly marl with a good proportion of clay, especially lower down the slope. Argovian (Jurassic) limestone provides the minerality for which these wines are famous. The wine displays a similar depth to the Meix Garnier, but is fruitier, like ‘Miss Armande’. There is more muscle, too, with raspberry and strawberry notes showing above slight oak and leading to a lengthy finish.

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret, 2019 Monthélie Premier Cru Le Meix Bataille ($69)

Domaine Monthélie-Douhairet-Porcheret, 2019 Monthélie Premier Cru Le Meix Bataille ($69)

The 5.6 acre ‘Le Meix Bataille’ vineyard sits on the hillside to the northeast and immediately above the village of Monthélie itself on the Volnay side; it is part of the main cluster of Premier Cru vineyards in the appellation that lie on south-facing slopes. Terroir is built around steep slopes with favorable exposures and soils made of the same Bathonian limestone that is found in some of Volnay’s more famous vineyards. The wine shows black cherry confit with discreet oak and fine-grained, vigorous tannins and rather intense minerality that gives is superb aging capability.

Domaine Thierry et Pascale Matrot

In 1914, Joseph Matrot and his wife Marguerite took up residence in Marguerite’s family home with the intention of developing the property into a respected wine estate. Over the course of several generations, Domaine Matrot expanded to fifty acres, and in 2000, began harvesting the vineyards organically.

From left: Adèle (left), Thierry, Pascale and Elsa Matrot

Of the change, Thierry Matrot says, “It’s not a revolution, it’s an evolution. Technology has made things easier, but our winemaking philosophy has changed very little. The vinification is about the same. We don’t use new oak for the village wines or the Premier Crus; we prefer to allow the terroir to express itself and to show the character of each vintage. And my father worked in just the same way.”

The estate extends across five villages, producing both regional appellations and several Premier Crus in Meursault and in neighbouring Puligny-Montrachet. Three quarters of the production is white and about 60% is destined for the export market.

Domaine Thierry et Pascale Matrot, 2019 Monthélie ($53)

Domaine Thierry et Pascale Matrot, 2019 Monthélie ($53)

From an acre of 40-plus-year-old vines just in front of the Clos des Chênes in Volnay. It shows a concentrated floral bouquet of iris and rose petal that complements crunchy red berries. The palate is well-balanced with a fine bead of acidity and a harmonious, long and elegant, Volnay-like finish.

- - -

Posted on 2023.09.27 in Côte de Beaune, Monthélie, Auxey-Duresses, Saint-Romain, France, Burgundy, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

The High Priestess of Biodynamics: Françoise Bedel, a Passionate Advocate of The Practice, Unlocks Meunier’s Potential in Champagne’s Rot and Frost Prone Western Fringe (4-Bottle Pack $399)

In a small estate that is closer to Paris than to Reims, Françoise Bedel has managed a remarkable feat: She has turned an acute family illness into a paradigm shift for much of the Champagne region.

From the village of Crouttes-sur-Marne, nestling the banks of the Marne River, Bedel discovered homeopathic medicine while trying to find a cure for her son Vincent’s hitherto untreatable condition. Vincent, now her winemaker, made a marked improvement, and this how Françoise’s journey to biodynamic viticulture began. In 1982, at a time when virtually no one in the wine world had even heard about it, let alone employed it, she realized that the health of the body and the health of the vineyard may be interchangeable concepts.

She says, “Biodynamics is way of thinking—about the earth, about ourselves, about wine.”

This month’s Champagne package is the output of such iconoclastic thinking—and the tale of wrenching victory from the jaws of illness, cold clay and climate change.

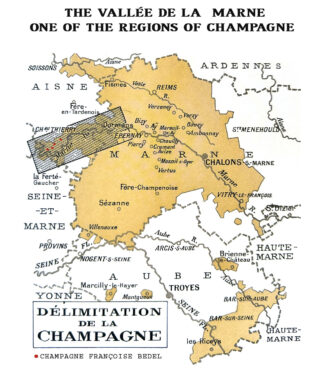

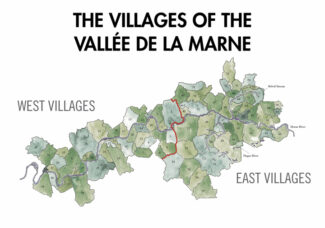

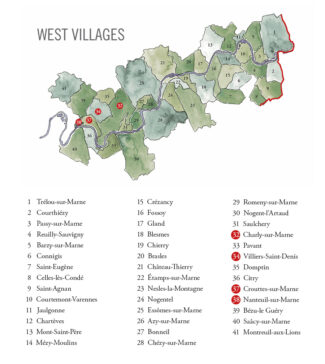

The Vallée de la Marne: Twists and Turns, Patchwork of Soils

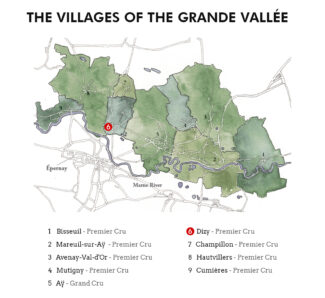

In strictly geographical terms, the Marne Valley extends from the city of Tours-sur-Marne to Château-Thierry. It stretches over sixty miles and through two départements, the Marne and the Aisne, all the way to the limits of Seine-et-Marne. As its name indicates, the Marne Valley follows the river, a landscape of rolling hills and small villages. Vines are planted on both banks although those on the north side benefit from a more favorable southern to eastern sun exposure.

The most famous villages are located at the eastern end of the valley around the city of Épernay, a ranking that reflects the importance given to the presence of chalk in the soil. Chardonnay and Pinot Noir dominate the vineyards of the eastern end of the region, and the major Champagne houses located here include Billecart-Salmon or Philiponnat in Mareuil-sur-Aÿ, Deutz and Bollinger at Aÿ and Jacquesson in Dizy.

West of Châtillon-sur-Marne, chalk tends to be found more deeply buried in the ground; the top soil is made of calcareous clay and clay marls. Meunier is the grape of choice in this part of the valley and it here that a new generation of experimental winemaker has flocked in order to deepen their own (and by proxy) our understanding of this variety.

Downriver in Champagne’s Western Fringe: Clay Descends Deeper

The farther west you go in Vallée de la Marne, the thicker the clay deposits become and the more contentious the weather grow; cold air sinks and follows the snaking river. It is in this somewhat inhospitable condition that Meunier begins to show its mettle. An also ran in much of Champagne, here it is king; among the 21,000 acres of Vallée de la Marne vineyard, especially in the west, about 72% is Meunier.

Although Pinot Noir and Chardonnay can both do well with less chalk and more marl, it is the triple threat of valley frost, fog and cooler, clay-heavy soil that tilts the scale towards Meunier. It also helps that the grape is a tad more resistant to botrytis than Pinot Noir or Chardonnay, along the host of other mildews that thrive in the damp, humid conditions encouraged by morning fogs that follow the river.

Meunier Comes Into Focus

A light juice and dark skin grape, Meunier tends to be considered the inferior of the three dominant grapes of Champagne, without the finesse, the liveliness or the delicateness of its illustrious counterparts, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Lately, Meunier has been experiencing a comeback and many up-and-coming winemakers are showcasing it in their range. 100% Meunier cuvées are becoming more common and single vineyard Meunier releases are available. In Baslieux-sous-Châtillon, Eric Taillet even launched the ‘Meunier Institut’, entirely dedicated to his (and Françoise Bedel’s) favorite grape.

Champagne Françoise Bedel

Original in Personality, Intensely Soil-Expressive

“For a wine to truly express terroir,” says Françoise Bedel, “one must respect the land’s qualities and characteristics as you would an individual’s personality.”

The 22 acres that make up Champagne Françoise Bedel are spread out on either side of the Marne, Crouttes-Sur-Marne, Nanteuil-Sur-Marne, Charly-Sur-Marne, and Villiers-Saint-Denis. Here vines are between 30 and 70 years old (79 percent meunier) and each plot boasts different subsoils, allowing for blending according to the terroirs and the elaboration of terroir-specific cuvées.

Françoise Bedel and son, Vincent

“These Champagnes are the expression of a rigorous method that brings out and enhances the qualities and particularities of the earth, the vines and the fruit,” Bedel says. “Because I love plants, life in contact with nature, and passing on a healthy land to the next generations, I have been cultivating my vineyard organically since 1998 on the entire estate.”

She is, in fact, only the second generation to tend these vineyards. Her parents, Fernand and Marie-Louise Bedel, turned over a portion of the estate to her in 1979 and with her son Vincent Desaubeau, who has now taken over as winemaker, she forges the future.

The key to the Bedel style is long lees aging, regardless of whether it is vintage or non-vintage; all cuvées go through at least 36 months on the lees in the cellars but more often than not, the wines are not released sooner than five years after harvest, offering pure, assertive flavors with a slight oxidation, equating to some of the finest expressions of Meunier in Vallée de la Marne, and arguably, the world.

Old Soils, New Farming

Compared to much of northern France, especially in the Paris Basin, the soil of Vallée de la Marne is still wet behind the eras. The further from the center of the basin, the older the deposits; Alsace and Burgundy, Metz and Dijon lie largely on Jurassic soils from between 150 and 200 million years old. Champagne, near the center of the depression, sits on soils between about 40 and 150 million years of age.

To this ancient earth Champagne Françoise Bedel brings innovative biodynamics, often numbered by ‘preparation’ and applied at various times in the lunar cycle.

Preparation 500, for example, is a manure concoction that reinforces subterranean biodiversity; vine roots lengthen, deepen and spread more densely and evenly in the soil. Preparation 501 is made of powdered quartz buried inside a cow’s horn, said to help in leaf development and initiating blossoming—it is applied early in the morning, at sunrise. Preparation Maria Thun is a compost of dynamized cow manure, reinforces the process of decomposition. According to Françoise Bedel, “All its ingredients contribute to the development of complex humus clay. A large number of microorganisms improves soil life. After years of research, Maria Thun [a German biodynamics authority who passed away in 2012] was able to document the cosmic influences on plants. The sun, the moon and all the other planets influence in their own manner life on this Earth, be it vegetal, animal, or human.”

Winemaking: Unlocking The Potential

Says Françoise Bedel: “Following my intuition, I propose Champagnes with a strong personality, which beyond being a media lure, has the potential to be a medium at the service of your well-being.”

Unlocking that potential has been the driving force behind the estate’s operations, field to cellar, by the day and by the decade. Nearly everything is done by taste and to pay homage to taste. As Françoise explains, “The date of the harvest is decided after tasting the grapes and analyzing the must from grapes that have just been pressed. The pressing operation is carried out entirely at the domain; a good pressing preserves the potential longevity of the wine by being carried out in a gentle manner. The fractioning of the juice from the different grape varieties and terroirs allows for an additional selection, again, by taste alone.”

She goes on: “We further unlock the potential of the harvest by vinifying partially in oak barrels to reinforce the richness and the aromatic complexity. The other part is vinified in small enameled vats to enhance the purity of the terroirs. The contents of each vat are clearly identified by the parcel of land and the racking is carried out under conditions that are in keeping with Maria Thun’s lunar calendar.”

Blending: A Leap Into The Future

As a painter chooses his pigments or composer writes a symphony with various instruments in harmony, the assemblage of a Champagne maker must take all elements, the obvious and the subtle, into consideration. And more: The essential notes of symphony will not change with time and the paintings in the Louvre are the same ones once viewed by our great grandparents. Wine, however, is a mutable substance, ever undergoing the ravages or the enhancements of time.

Rather than paint or musical notes, the raw material of wine is geology, exposure, place of origin and specific parcels contribute to the organoleptic qualities of grape juice. The marriage of aromatics and flavors to create a synergistic whole is the art of the cellar master; many tests are carried out and multiple opinions gathered before proceeding with final blends. These decisions are critical since the outcome is irreversible and unique, intended to express the personality and preferences of the winemaker.

“The actual blending is a leap into the future,” says Françoise. “In point of time, it is never rushed; it can take from a few days to a few weeks.”

Bedel’s Multi-Village Champagne

The villages of Champagne each carry with them individual stories—some approaching a legendary status; 319 of them, under the system called the Échelle des Crus, are rated on a scale with ascending degrees of excellence. A winemaker, following strictures, may label Champagne with the name of a specific village or combine several in the foundational regional concept of blends.

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Origin’elle’, Brut ($91)

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Origin’elle’, Brut ($91)

Predominantly 2017 with reserve wines. 70% Meunier, 20% Chardonnay, 10% Pinot Noir, relying on a terroirs (both silty limestone and calcareous clay) intended to produce a Champagne that emphasizes freshness and crisp primary fruit flavors. It is fermented in enamel-lined tanks and neutral French oak barrels and sees 3 years of aging sur latte before disgorgement; finished with a minimal dosage of 1.6 grams/liter. Disgorgement Date: April 2021.

Bedel’s Site-Specific Expressions

Traditionally, of course, Champagne is a blend of wines from a particular year, often from separate plots, mixed with reserve wines from previous harvests. This is a technique which has allowed a winemaker to ensure that his wine has a certain taste stability—a house style that remains constant from one year to the next. Otherwise, as in much of the wine world, a label tends to reflect only an estate while the product changes in taste and quality depending on the year and the climate.

Plot specific wines, known as lieux-dits in Burgundy, are based on the theory that certain groupings of vines have unique characteristics that directly influence the development and aromatic concentration of the grapes. These are usually natural conditions specific to the vineyard location, such as its orientation, the presence of a forest or a mineral outcrop on the surface. In Champagne, a ‘clos’ is usually a walled-off portion of a vineyard identified by a winegrower for its natural potential. This artificial barrier creates a microclimate specific to this plot which will, over the years, develop its own aromatic identity. Given these specificities, one can better understand why many of the winegrowers who are lucky enough to own such plots of land decide to produce cuvées that are parcel-based and very often vintage wines.

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Dis, “Vin Secret”‘, Extra-Brut ($140)

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Dis, “Vin Secret”‘, Extra-Brut ($140)

Predominantly 2015 with reserve wines. 95% Meunier, 5% Pinot Noir; biodynamics informs the discreet minerality of ‘Say, Secret Wine’ which braces notes apple pie, freshly-baked croissant, quince and buttercream frosting ending with a vibrant note of baking spice. Disgorgement Date: June 2021.

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Entre Ciel et Terre’, Harvest 2015, Extra-Brut ($105)

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘Entre Ciel et Terre’, Harvest 2015, Extra-Brut ($105)

Predominantly 2015 with reserve wines. Half Meunier, 20% Chardonnay and 30% Pinot Noir, ‘Between Heaven and Earth’ is extra-brut Champagne made from vines between 30 and 70 years old. After spending three years sur latte, the wine produced is fresh, aromatic nose reminiscent of white acacia and, on the explosive palate, offers clover honey and spice bread. Disgorgement Date: June 2021.

Bedel’s Vintage Champagne

No mumbo-jumbo wine lexicography here; vintage Champagne is made from the harvest of a single year. As it is generally only made in superior vintages, frequently only three to four times every decade, it may fairly be viewed as an indicator of quality.

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘L’Âme de la Terre’, 2010 Extra-Brut ($117)

Champagne Françoise Bedel ‘L’Âme de la Terre’, 2010 Extra-Brut ($117)

From the 2010 vintage, ‘The Soul of the Earth’ was tasted blind by Françoise Bedel before it received the final go-ahead to be declared a vintage. 90% Chardonnay with 5% each of Pinot Noir and Meunier, the wine spent a full decade ‘sur latte’, or stacked on racks to develop in the bottle in a cellar environment. The wine reflects the intensity of Madame Bedel’s personality and is a tour de force for the estate, showing generous fruitiness, tropical as well as rich and generous stone fruits, sapid on the palate with tension and backbone and a lovely savory finish. Disgorgement Date: November 2021.

Notebook ….

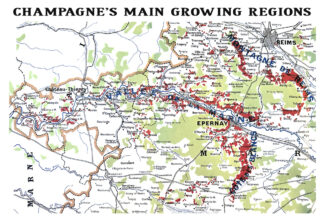

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

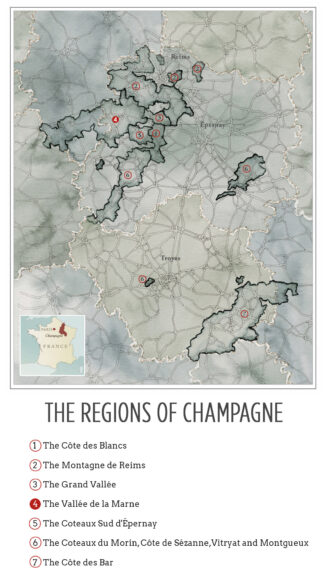

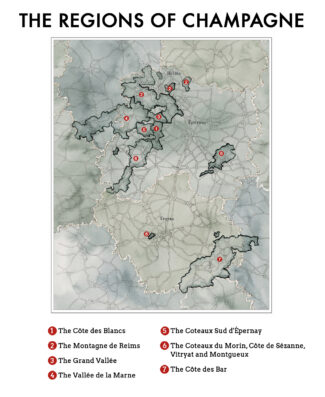

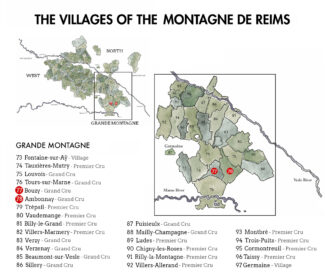

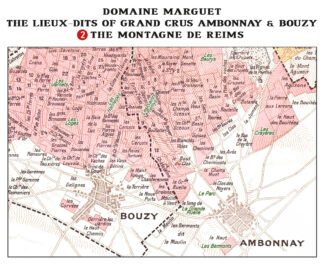

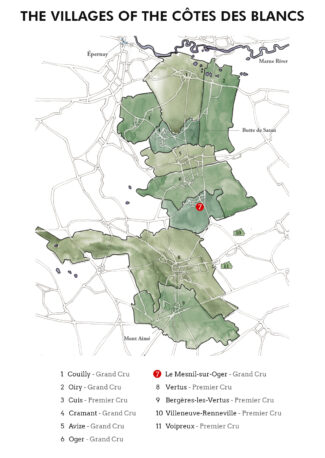

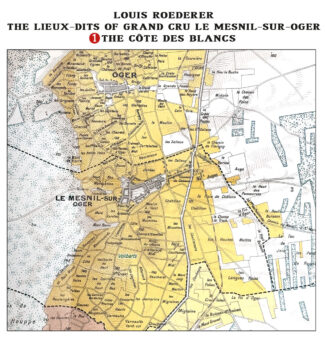

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

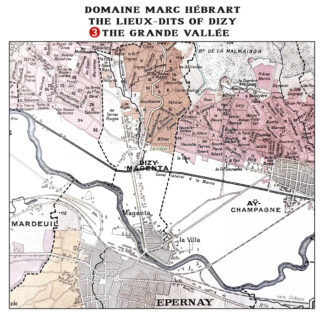

The lauded wine writer Peter Liem expands the number of sub-regions from four to seven, dividing the Vallée de la Marne into the Grand Vallée and the Vallée de la Marne; adding the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay and combining the disparate zones between the heart of Champagne and Côte de Bar into a single sub-zone.

Lying beyond even Liem’s overview is a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that compliment or contrast when final cuvées are created.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Épernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

Three Primary Varieties and Four Heirloom Grapes

Champagne, with few exceptions, is a blended wine. Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Meunier are the trinity that form the bulk of these blends; a handful of heirloom grapes that have official government sanction in certain locations within the AOP.

Although they make up fewer than 0.3% of planted acres, with the dramatics being wrought by climate change, these other varieties may find a more prominent role in future blends:

Arbane is a late-ripening variety that succumbs easily to bad weather, and yet—under ideal conditions—produces a Champagne with remarkable finesse, offering nuanced notes of hawthorn blossom and carnation and as well as peach, apple and quince.

Petit Meslier is another milktoast variety, highly susceptible to disease and frost. But when it produces, it does so with both barrels, bringing a smoky quality to the wine that makes it identifiable, even when used in small quantities.

Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc, both white cousins to red Pinot Noir are low in acidity and somewhat easier to work with than Arbane or Meslier, although like Pinot Noir, Gris may be somewhat finicky. Both bring to blend their own magic; Gris offers a nutty quality to the finished wine and Pinot Gris adds punch and body.

- - -

Posted on in France, Champagne, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

Saint-Julien Channels Pauillac: In Search of Purity, Precision and an Assertive Style, Bordeaux’s Château Ducru-Beaucaillou Achieves All in Their 300th Vintage Release, 2019 (3-Bottle Package $393)

Join Us for Saturday Sips

Come as you are; come any time that’s convenient for you during our business hours to sample from this week’s selections. Our staff will be on hand to discuss nuances of the wines, the terroirs reflected, and the Château.

If ever an estate has enshrined within its very name the fact that grapes thrive where other crops fail, it is Château Ducru-Beaucaillou: The famous lieu-dit of Beaucaillou (good pebbles) was once called Maucaillou (bad pebbles) when they tried to grow cereal crops instead of grapevines. It is the deep Günzian gravel that earns the terroir both scorn and praise from farmers (depending on crop; along with soil, a favorable climate and the general wherewithal of generations of vignerons, Ducru-Beaucaillou’s reputation has held strong—and grown—for three centuries. Vintage 2019 marks this very milestone and the estate’s outspoken owner Bruno-Eugène Borie considers it a spectacular vintage in which the château’s legendary purity, precision and assertive style is on full display.

This week’s package offers a fascinating peek behind the curtain at Ducru-Beaucaillou to see how climate change has restructured priorities and bred innovation, and how the leadership of Bruno Borie has led to a number of incredible undertakings, including re-corking a full inventory of 40 vintages (1950 and 1990) in an oxygen-free environment, giving them an extended life of 50 more years.

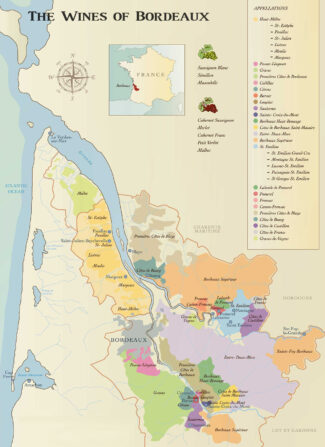

Saint-Julien & Pauillac: Neighboring Communes

The most singularly revered appellation on earth, Pauillac is to wine what The Beatles are to pop music. Though fewer than ten square miles in total, three of the top five châteaux in the 1855 Médoc Classification are located here, and so varied is the topography that each estate is able to market the individual nature, in style and substance, of their wares. And it is this trio of skills—growing, producing and selling—that has made the region almost a cliché, synonymous with elite wine, where futures sell for exorbitant rates long before the wine is even in the bottle.

Great things come in small packages, especially when big money is involved. Saint-Julien—the smallest of the major Médoc appellations at under four-square miles—also boasts (through a series of real estate deals between the large estates and the small ones) an astonishing pedigree: Fully 95% of the appellation sits on classified acreage. Key to the desirability of the wines produced here is the seamless fusion of concentration and elegance; the wines are of a style historically referred to as masculine, but held to standards of manhood in the mode of a Knight Templar before a brawny warrior. This blend of finesse and fortitude comes in part from the preponderance of gravel in the best vineyards, allowing natural drainage in the wet years, radiating warmth in cool vintages, extending the growing season and allowing vine roots to extend deeply into the earth.

omne trium perfectum

300th Vintage Release: Three-Bottle Package ($393)

The estate’s 300th anniversary was blessed with magnificent growing conditions, which brought forth a wine of particular distinction. Ideal levels of rain (falling mostly at night, guaranteeing freshness) while clear days and cool nights in September, together with a heatwave in the middle of the month, helped to concentrate the fruit and ripen the very fine tannins.

The wine package we offer this week includes one bottle of the special Tercentenary bottling of Château Ducru-Beaucaillou 2019 and two bottles of 2019 ‘La Croix Ducru-Beaucaillou’ which hails from a separate vineyard and yet is considered one of the best second labels in the business.

Château Ducru-Beaucaillou

Passion Perfects Nature’s Opus

Beside the poetry in a rhyming name, this hallowed Second Growth estate, given high praises in the 1855 classification, has produced the best wines in its history in the 21st century. This is credit to the Borie family, who bought the château in 1941.The current helmsman is Bruno, who grew up on the estate: “I was born and raised at Beaucaillou and I have always been immersed in this country landscape and lifestyle, in the vineyards and the pastures, cattle and all; I basked in the fascinating environment of the cellars, where the transmutation of the grape juice into wine, and then the slow maturation of the young wine into these magical elixirs takes place.”

He learned the magic of wine early, but to nail down the business and technical end, he spent time in California as a winery intern before becoming the Commercial Director for P.A. Sichel and the CEO of Lillet, the Bordeaux aperitif. He began to manage Beaucaillou in 2003, where he was instantly confronted with the excessive heat the Bordeaux had begun to suffer with global warming. This required that he embark upon a paradigm shift to tackle the changing climate, and it perseveres to the day: “My first major decision was to not have a preconceived agenda,” says Bruno, “but rather to listen to nature and try to tailor our approach accordingly. For 2003, this meant very little leaf thinning to keep bunches shaded and protected from the scorching rays of the sun.”

These days, Borie relies on a number of quality initiatives, including more selective harvesting and establishing more organic farming practices: “We now cultivate and plough various grasses and legumes to help aerate the soil,” he explains. “This increases biodiversity, and the quantities of critical nutrients. When replanting vineyards, we leave our plots fallow for five years, during which time we perform a deep ploughing to reduce compaction, and then cultivate various grasses in rotation to help preserve our precious soils.”

The Vineyard: Maucaillou, Beaucaillou

The clock began to tick towards Château Ducru-Beaucaillou’s tercentennial hurrah in 1720, when Jacques de Bergeron married Marie Dejean, whose dowry included land known as Maucaillou, a name formed as a portmanteau of the French words ‘mauvaise’ and ‘cailloux’ meaning ‘bad pebbles’. The first records of the name change from ‘bad’ to ‘good’ is 1760.

The titular stones, good or bad, are quartz pebbles swept in by the ancient Garonne river at the beginning of the early Quaternary Period, about two million years ago. Beyond the gems it produces in the cellar, terroir so blessed also offer rich lithological finds like Lydian jasper and agatoids. The gravel is less kind to plants, giving rise to poor soils—a condition to which grape vines are well suited. Their vast network of roots, snaking through the gravel, are able to draw nutrients from far below. A bonus is that in cooler weather, the stones retain daytime heat and return it to the vines at night to facilitate the ripening of the grapes.

Ducru-Beaucaillou’s proximity to the vast Gironde River estuary—where four daily tides mitigate the rigors of winter and moderate the summer heatwaves—may also deflect the trajectory of hailstorms. The vineyard is located to take advantage of these natural features, beginning immediately above the low-lying marshland of the Gironde, about three hundred yards from the estuary and extending to the west, ending at a slight elevation that offers natural drainage of rainwater into the Gironde or the tiny Mouline brook to the north.

Bruno Borie: Works To Balance Centuries Of Tradition With Contemporary Viticulture

“I was born in 1956 and raised in Ducru-Beaucaillou,” say Bruno Borie. “I was truly a country boy, preferring to run through vineyards and meadows than taking walks in the town. I enjoyed the company of the winegrowers and loved taking part in the various jobs, including, of course, the harvest.”

Bruno-Eugène Borie, Château Ducru-Beaucaillou

In his years exploring the vineyard as a living entity as well as a financial concern, Borie has developed a deeply personal philosophy about his role: “We help the vineyard give birth to wine. Nature can do it all; we are here to allow nature to express and share the best of herself. I am here to make Ducru-Beaucaillou, not just another Cabernet Sauvignon or another Cru Classé.”

To this end, he has overseen significant changes in Beaucaillou viticulture, introducing new techniques and reviving forgotten practices, looking both towards the past and modern science. Although he considers biodynamics to be more esoteric than scientific, the entire vineyard was certified HVE 3 in 2016 and he eschews the use of herbicides and pesticides. Emmanuel Bonneau joined the team as technical director in 2016, and is currently researching phytotherapy (the medicinal use of medicinal plants and herbs) to tackle mildew, while lightweight robots reduce soil compaction.

“The most crucial element in making fine wine is to be close to the plant and its ecosystem,” Bruno explains. “Our system of pruning, for example, consists of preparing the vine not only for next year, but following ones. Therefore, it must be the same person who prunes from one year to another because he ‘reads’ each vine the same way. Each of our vignerons is assigned a selection of plots for all seasonal vineyard operations which fosters a deeper connection with the vines through continuity. This ensures that our approach is the most adapted for our environment and our vines.”

The Harvest: The When And Why

The decision of when to harvest is a complex one, and it would be fair to say that every estate has their own formula though which they determine picking schedules, based both on weather and the style of wine they’re after. It’s no different at Beaucaillou, where, according to Bruno, “We pick each plot when fruit is at optimal ripeness and then seek to preserve its purity and enable it to express its terroir fully. We also consider blending compatibility for harvest date. For example, the 5-15% of Merlot in the blend of Ducru needs to be Médoc-like in style. It must be compatible with Cabernet with typicity, freshness and elegance to counterbalance Merlots that are overly rich. To determine the precise harvest date for each plot, we collect and analyze the critical measures (sugar, IBMP, acidity, pH), but the final decision is based entirely on taste.”

Winemaking: Selection And Precision

A combination of artisan methods and new innovations form the backbone of Château Ducru-Beaucaillou’s cellar tenets; leading the second category is the use of conical wooden ‘Smart Vats’ for the Grand Vin. Smart Vats have a number of advantages, including automatic and gentle remontage that can be fractioned over 24 hours with complete oxygen control for extreme precision, analyzing and storing relevant data on sugar, density and oxygen throughout cuvaison, allowing a refinement of approach and data saved for current decisions and future reference.

The traditional methods that Borie employs includes ‘slow hand’ extraction: First come a cold maceration, then gentle remontage in the earlier phases of fermentation when critical decisions are made by taste and tanks are sampled several times per day. The goal, according to Borie, is the extract noble tannins with the most refined grains, giving the ‘draped cashmere’ mouthfeel for which Ducru-Beaucaillou is widely praised.

“Of course, we consider the data,” Borie says, “and Smart Vats enable us to conduct our extractions with even more precision to achieve this goal. In the end, science allows us to make better art.”

2019 Vintage: Low Yields But Pure, Aromatic And Well-balanced

Like much of the Left Bank, the 2019 growing season for Saint-Julien began with a mild, if lackluster spring that saw cool temperatures and patches of rain in the run-up to the summer months (although rainfall was still less than in other Bordeaux appellations, leading to lower yields than average). A warm, dry summer ensured the grapes reached phenolic ripeness and, bar some rainfall towards the end of the season, conditions remained smooth and easy for a seamless harvest.

The resulting grapes were extremely healthy, and naturally, this translates to the wines. In general, the wines are sophisticated and powerful with rich, dark fruit and velvety tannins while still retaining delicate aromatics. The best 2019s exhibit the ideal balance between fruit, acid, alcohol and tannin needed for long-term aging. Although many of the wines will make very pleasant early drinking, the top examples should be able to cellar for many years to come.

2019 At Ducru-Beaucaillou: Cabernet Sauvignon Is Key

So hot was the summer of 2003—the year that Bruno Borie took over Ducru-Beaucaillou—that he knew that winemaking in Bordeaux would likely never be the same. Going forward, weather, rather than tradition, would dictate work in the vineyard. Harvest dates were creeping forward and August vacations were a thing of the past. 2019 was another hot season, and Bruno realized that this sort of weather pattern was ideal for Cabernet Sauvignon, a thick-skinned variety that requires a lot of accumulated heat and sunlight hours to fully ripen.

He says, “With warmer summers like 2019, the fruit is richer and more concentrated with longer length, and the thick skins, which ripen during the final phase, can fully ripen, giving deeply colored wines with high levels of extremely fine-grained, ultra-silky tannins. At Ducru, we have three key strengths as we face climate change: privileged terroirs, the dominance of Cabernet Sauvignon, and of course highly invested and competent technical teams, including Cellar Master René Lusseau and Oenologist Consultant Eric Boissenot.”

2019 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($245) (1 BOTTLE)

2019 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($245) (1 BOTTLE)

80% Cabernet Sauvignon and 20% Merlot matured for 18 months in 100% new French oak. Purple-black in color, the 2019 Ducru-Beaucaillou explodes from the glass with notes of cassis, blueberry pie and plum preserves behind hints of candied violets, dark chocolate, licorice, crushed rocks and freshly-overturned soil with a touch of mossy bark—a wine whose finish passes the 60-second mark with ease.

2019 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou ‘La Croix Ducru-Beaucaillou’, Saint-Julien ($74) (2 BOTTLES)

2019 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou ‘La Croix Ducru-Beaucaillou’, Saint-Julien ($74) (2 BOTTLES)

The estate does not market La Croix Ducru-Beaucaillou as a ‘second wine’ because it comes from a different source: an inland vineyard on the south bank of the La Mouline stream close to Château Talbot; it was previously sold as Château Terrey-Gros-Caillou. It consists of 91 acres planted with 65% Cabernet Sauvignon, 25% Merlot, 5% Cabernet Franc and 5% Petit Verdot. The breeding is made for 60% in new oak barrels 12 months, producing a muscular yet fresh wine, displaying a full range of berry, lavender rose petal, mint, spice and gravel inflections.

Time Capsules

A Half-Century of Ducru-Beaucaillou

As Bruno Borie carefully recorked all vintages between 1930 and 1990, this divine diorama looks at some of the top vintages from the estate of the past half-century—so many, in fact, that it frequently said that Ducru-Beaucaillou is a Second Growth that deserves First Growth status.

2010: A Promise of Longevity

Recognized as legendary across the board, 2010 was truly great vintage whose exceedingly dry growing season served to concentrate the juice and provide wines with outstanding depth.

Despite a wet June giving a damp start to summer, the season soon heated up turning exceedingly hot and dry, particularly in the Médoc region; the arid conditions caused the right amount of water stress to improve the berries, and the long, sunny days continued through to October with nights steadily chilling as the season drew to a close. Cool nights were imperative to preserving the acidity in the grapes and rains, fortunately, came in September freshening the grapes.

2010 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($550)

2010 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($550)

Just beginning to fully open up, the wine is now entering a drinking window that should last two more decades at least. A sensuous nose offers layers of blackberry paste and warm ganache, steeped fig and pastis-soaked plum flavors. The structure is massive yet polished, and the fruit displays purity through a graphite-supported finish. Large-scale and extremely well-rendered. 8,416 cases made.

2000: A Stunning Vintage, Closer To Maturity

A mild, warm winter followed by a wet spring made mildew a threat, but from July onwards, a spectacular summer dominated Saint-Julien with hardly any rain until mid-September. Sunny weather then returned for the October harvest, broken by a single day of rain—a boon to parched vines. Producers who picked early risked unripe wines and others who picked later risked jamminess, but for the majority who picked at the right time, the vintage offers fantastic rewards.

2000 Château Ducru Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($490)

2000 Château Ducru Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($490)

70% Cabernet Sauvignon and 30% Merlot, the truly stunning garnet-brick colored 2000 Ducru-Beaucaillou offers flamboyant scents of baked black currants, raisin cake, prunes, Chinese five spice and eucalyptus plus touches of cigar box, new leather and cast iron pan. It will continue to improve, too.

1983: Fully Mature

1983’s growing season in Saint-Julien began with a cold winter and chilly, wet spring. Balmy conditions settled in shortly afterward, allowing for a near-perfect budburst and flowering, and, despite a brief cool patch, temperatures than rocketed in July with the month even proving a record breaker. Drought was a problem but only through August, which brought plenty of rain. September brought drier, sunnier conditions and a run of good days in the lead-up to the harvest ensured the resulting crop was in good health. The harvest began towards the end of September and ran through to October, producing a generous but good-quality crop.

1983 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($2,400) DOUBLE-MAGNUM

1983 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($2,400) DOUBLE-MAGNUM

Although some ‘83s lacked the structure for long term again, large format bottles age at a much more leisurely pace, and thus, are ideal to experience the nuance changes in this full-bodied wine showing blackberry and hazelnut behind a beautiful base of gravelly soil tones, cigar ash and a touch of juniper berry. Perhaps currently drinking at its apogee, the wine is svelte and pure on the attack with melting tannins and a long, complex and seamlessly balanced finish.

1978: The Miracle Vintage

Known as the ‘Miracle Vintage’, 1978 began with a damp, chilly spring that affected both bud break and flowering. Conditions eventually improved, but it was not until the end of the summer the weather had sufficiently warmed up and dried out. There followed a string of idyllic, sunny days, perfect for bringing the crop to phenolic ripeness and these perfect conditions late in the season rescued the vintage from possible disaster—the so called ‘miracle.’ The heavy rains of October came late, holding off until all the fruit had been picked—another manifestation of the miracle.

1978 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($450)

1978 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou, Saint-Julien ($450)

‘78 Ducru is considered one of the unequivocal successes from this vintage. From the outset, the well-developed bouquet of licorice, earth, black currants, and underbrush shone none of the vegetal character found in many wines of the vintage. Now fully mature, the medium-bodied Saint-Julien gem exhibits soft tannin, excellent concentration and purity, and a sweet, elegant finish.

- - -

Posted on 2023.09.08 in Pauillac, Saint Julien, France, Bordeaux, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

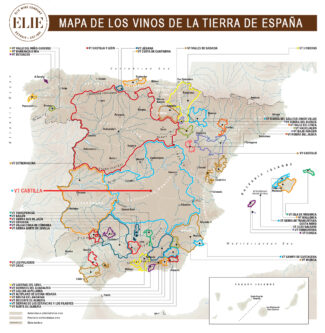

Fanfare For The Uncommon Grape: Visionary Spanish Producers Explore The Capabilities of 23 Heritage Varieties’ and Demonstrate Their Potential For Complexity. A Dozen: 7 Red, 4 White & 1 Rosé $296

The wine world’s equivalent to the dinosaur-destroying Chicxulub meteor is a microscopic louse called phylloxera. By the end of the nineteenth century, the bug had killed most of the vines in Europe, and when they were replanted (often using louse-resistant American rootstock) the focus tended to be on resilient varieties capable of producing the most fruit. This was a desperation move; a means of recouping losses and ensuring that the industry could survive. Today, of the ten thousand grape varieties, only 13 of them occupy more than a third of the world’s total vineyard surface.

Wines of the Future That Look to the Past

In Spain, nostalgia and commerce have joined hands to resurrect a number of heirloom grapes, some of which were all but extinct and only found in a few isolated back-country pockets. This week’s package will echo Victor Frankenstein’s cry of delight “It’s alive!” by showcasing the second incarnation of many indigenous Spanish grapes. It is not only a historical cornucopia, but a collection of tastes and flavors that have nearly been forgotten.

Keep in mind, these grapes are the scrappers—tough little fighters who have made it into the twenty-first century despite the odds. As such, they are looked to as a window to the future, when climate change is making conventional grapes less comfortable with their terroir. Learn to pronounce the names below, because you may find it necessary to speak them aloud in the years to come.

The Quest to Recover Heirloom Varieties

Miguel Torres Maczassek, president of the extensive Cataluyan winery Familia Torres, describes his father’s mission to revive varieties that survived the phylloxera crisis: “There were once many more varieties than the ones that we know today. But the vineyard infestation, which nearly decimated an entire industry, also created a reckoning. Post-phylloxera, winemakers cultivated varieties guaranteed to do well in the climate, or turned toward more fashionable grapes that held international appeal. My father’s project was philanthropic project. In his mind, it was not only to make a wine, but to have a botanical collection.”

Other Spanish bodegas have taken up a similar challenge, and the overall lesson learned? It isn’t as easy as it sounds. Once a vine has been designated an ‘ancestral variety’, the hard work begins: Vines of that age are riddled with disease, and the viticulturists need pristine plant material for further experiments. So the vine must be reproduced multiple times in a greenhouse using new cells over several growth cycles until it’s given a clean bill of health.

And even then it takes time to understand a heritage vine’s individual nature, requiring several harvests. Like all grapes, terroir plays an irreplaceable role in finding the ideal site to bring out desired qualities, and finding this happy place may also take many vintages. And even then, the vine must reach the level of maturity required to produce acceptable wine.

On average, therefore, it is 14 years between the discovery of a heritage varieties and the time it is viable for winemaking.

“It’s been surprising that we find varieties that we need so much today,” concludes Torres Maczassek: “Here in the Penedès with the climate change, with the heat and the lack of rain, we are finding varieties that ripen late that have good acidity—this is a gift that came from nature. I cannot ask for more. These are the varieties that probably our children will use.”

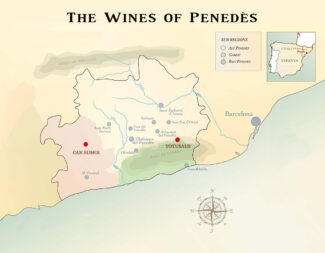

Catalunya

When Wine Becomes Crucial to Cultural Identity

The Catalan provinces of Barcelona, Tarragona, Lleida and Girona remain a part of Spain, but if you ask the residents, four of five of them will tell you they shouldn’t be. One of the most fiercely independent territories in the world, Catalunya is designated as a nationality by its Statute of Autonomy, and this is based on language, culture and administrative/political motivations.

And of course, wine.

As Catalan worldview differs from those of their Castilian, Galician and Andalusian countrymen, Catalan wine has little in common with those from the rest of Spain. There are ten denominated wine regions that focus mostly on familiar Mediterranean grape varieties, primarily Grenache and Carignan (also called Carinyena or Samsó) among red grapes, as well as Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah and Trepat. White varieties Parellada, Xarel-lo and Macabeo (called Viura in Rioja) that are primarily used for the production of Cava, the region’s premier sparkling wine and perhaps the most universally loved—and representative—of Spanish wines.

Tutusaus

Based at Can Tutusaus, in the center of the remote village of Olesa de Bonesvalls in the Garraf Natural Park, Tutusaus has become a pet project of husband Raimon Badell and wife Anna, whose award-winning Cava is proudly featured on the shelves here at Elie’s. As a team, Raimon and Anna have replanted ancient terraces in a rocky landscape otherwise dominated by pine trees interspersed with glimpses of the Mediterranean Sea. The oldest vines at Tutusaus were planted by Raimon’s father during a last-century’s craze for international grape varieties, and the Merlot remains an outstanding Spanish example of this variety.

The estate and its surrounding pine groves has stood since 1348, but it was only in 1729 that the country house was rebuilt within the village of Olesa, where the cellar is presently situated. The property comprises several acres of olive groves—resuscitated after years of neglect—and about thirty acres of vines. The rest is a maze of pine and oak forests, dwarf shrubs, brooms, fennel, rosemary, thyme, lavender and dwarf palms.

Raimon Badell, Tutusaus

In 1987, seduced by this mysterious land, Joan Badell bottled his first wines and planted his first trained vines. In 1999, his son Raimon, who was then studying oenology, became a close collaborator and opted to turn the estate toward ecological and biodynamic agriculture.

“Bottling the land,” is the way that Raimon Badell describes his interpretation of winemaking. “We only work with grapes picked from this estate,” says Rai, “where vines are situated between 800 and 1500 feet above sea level, bordering the Natural Park of the Massif of Garraf. The vineyards grow on hills with calcareous-clay soil and produce where the climate is distinctly Mediterranean, strongly influenced by the vicinity of the sea.”

Marselan

Marselan is a red French wine grape, a cross between Cabernet Sauvignon and Grenache. It is a niche variety, and not one of the rescued orphan grapes that survived phylloxera—it was first bred in 1961 by Paul Truel near the French town of Marseillan from which it takes its name. Wines made from Marselan tend to be medium-bodied with fine tannins, good color and display characteristic notes of cherry and cassis.

•1• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2021 Penedès Red ‘Marselan’ ($18)

•1• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2021 Penedès Red ‘Marselan’ ($18)

Although Marselan is frequently used as a base wine for blends, this is 100% Marselan hand-harvested from Badell’s estate in Alt Penedès, located entirely with the national protected area of the Massís del Garraf. The grapes are pressed and fermented in temperature-controlled, stainless steel 3,000-liter vats, then aged for 3 months before bottling. It shows the exuberant fruit-centered ripeness of Grenache and the elegant structure of Cabernet Sauvignon.

•2• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2022 Penedès Rose ($18)

•2• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2022 Penedès Rose ($18)

100% Marselan Rosé. The grapes are pressed and left in contact with the skins for several hours and fermented for 17 days in temperature-controlled, stainless steel 3,000-liter vats. The wine shows a springtime bouquet of young strawberries, raspberries and touch of minerality.

Xarel-lo

All the exotic mysteries of Catalunya may be contained within a single word, Xarel-lo, which in its correct spelling contains a diacritic scarcely known outside the region—a small dot where we have placed a dash. It’s called a ‘punt volat’—a flying point, and indicates a glottal pause. The pronunciation, somewhere in the neighborhood of ‘shah (or ‘chah)-REL-LO’ introduces you to the most aromatic of the Cava trinity; it also makes a heady, hallowed still wine that ranks among Spain’s finest whites. Not only is it delicious, the grape is rich in polyphenols and high in the antioxidant resveratrol, often associated with red grapes and the mystery behind the formerly ballyhooed ‘French Paradox.’

•3• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2021 Penedès White ‘Xarl-lo’ ($18)

•3• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2021 Penedès White ‘Xarl-lo’ ($18)

The grapes for this 100% Xarel-lo are hand harvested from Raimon Badell’s estate in Alt Penedès, which is located entirely with the national protected area of the Massís del Garraf. The grapes are pressed and fermented in temperature-controlled, stainless steel 3,000-liter vats, then aged in contact with fine lees for a period of 3 months before bottling. The wine shows straw yellow; the aroma filled with citrus, peach, flowers and herbs that follows through the delicate fruity taste and soft tannins in a long finish.

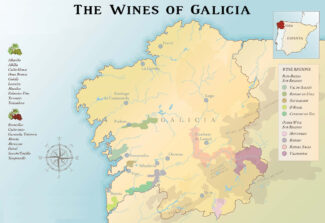

Galicia

Farming With Care and Sensitivity, Experimenting With Different Methods of Winemaking

Occupying the northwest corner of the Iberian Peninsula and exposed on two sides to the Atlantic Ocean, Galician wines are shaped by winds and waves. Best known for its Rías Baixas, a crisp, slightly fizzy and aromatic wine made predominantly from Albariño, there is a two-way stylistic influence with Minho (particularly Vinho Verde), just across the border in Portugal.

Over the past few decades, winemakers in Galicia have become increasingly aware of the potential of their prize grape, and locals have discovered that Albariño bears a striking resemblance to Riesling in the purity of its aroma and surprising its ability to age in bottle. Experimentation has been rife, including barrel-aging and judiciously applied malolactic fermentation to scale back the acidity.

Coto de Gomariz

Coto de Gomariz is located in an ideal winegrowing zone near the eastern edge of Galicia, where the slopes overlook the Avia River. The 66 acres were the brainchild of Ricardo Carreiro, who makes the most of the unique microclimate (schist, granite and sandy soils) through a cornucopia of local wine varieties including Treixadura, Godello, Loureira and Albariño. At the turn of this century, Carreiro upgraded the entire estate with integrated architecture and modern installations that allow for the annual production of nearly 200,000 bottles of wine.

Ricardo Carreiro, middle, and team, Coto de Gomariz

Sousón

Largely unknown outside Galicia, Sousón is the most widely-planted red grape in Rías Baixas, and is genetically identical to Loureira Tinta. It is a late-budding variety that matures slowly, so it well suited to warmer areas and south-facing plots. Because of longer hang times, Sousón can reach high levels of alcohol, between 12.5 and 14 degrees, with enough acidity to permit extended barrel aging. As a rule, Sousón showcases dark fruits (blackberries and currants) and is often used as a blending grape, although the experiment-prone wine Galician winemakers are increasingly using it as a stand-alone variety.

•4• Gomariz ‘Flower and the Bee – Souson’, 2020 Ribeiro ($21)

•4• Gomariz ‘Flower and the Bee – Souson’, 2020 Ribeiro ($21)

Wine begins with a flower and a bee, and so strongly is this fact imprinted on the folks at Coto de Gomariz that in 2013 they changed their name to ‘A Flor e a Abella’. This 100% Sousón is made from the youngest vines within the Gomariz parish and grown on soil that is predominantly sandy. Cherry red with a violet rim, the wine brims with aromas of forest berries with a savory yeasty undertone.

Ferrol & Caiño

Ferrol, also called ‘Ferron’, is a rich red native Galician grape that is often used to bring aroma and structure to blends. It’s a vigorous variety, naturally resistant to mildew and botrytis, and based on the exposure of the vines, it may retain a bracing level of acidity after fermentation.

Caiño is a grape not found outside Galicia and Portugal’s Minho. It is known for making acid-driven red wines that rarely exceed medium body weight. However, the grape has thick skins and high tannins, leading many winemakers to vinify it using the carbonic maceration technique favored in Beaujolais.

•5• Wish ‘Viño de Encostas Xose-Lois Sebio’, 2018 Galicia ($45)

•5• Wish ‘Viño de Encostas Xose-Lois Sebio’, 2018 Galicia ($45)

‘Viños de Encostas’ is a personal project of highly-esteemed winemaker Xosé Lois Sebio, formerly of Coto de Gomariz. It consists of small-lot wines coming from northwest Spain. Meaning, ‘Wines of the Hills,’ Viños de Encostas features only the top fruit of each region that Sebio has planted or works closely with in hilly and steeper zones. ‘Wish’ is a field-blend of native varietals fermented in open vats; it undergoes malolactic to temper the acidity and rests for 18 months is used oak barrels. The resulting wine is silky and bright with lilac notes behind blueberry and cherry.

Albariño

Albariño is almost a synonym for Rías Baixas, where it makes up 90% of the plantings. It has traditionally been viewed as a fresh, aromatic, hardy variety that makes light, peach-tinted wines, although thanks to the introspection of a handful of Spanish winemakers, it is now seen to be a wine capable of a remarkable maturation within the bottle.

Ultra-modern styles of Albariño are richer and more textural, having been aged on their lees and given some time in to add complexity and a touch of creaminess.

•6• Coto de Gomariz ‘X’, 2021 Ribeiro ($30)

•6• Coto de Gomariz ‘X’, 2021 Ribeiro ($30)

95% Albariño, 5% Treixadura from two unique plots—‘As Penelas’ with schist soils (in Gomariz) and from ‘O Taboleiro’ with sandy granite soils. This wine originates far from the influence of the sea, resulting in a much more mature and complex wine than those of coastal Rías Baixas. The ‘X’ is a nod to the Gallego word ‘xisto’, or ‘schist’—the granitic soil that is characteristic of this region.

Treixadura

Called ‘the Jewel of Ribeiro’, Treixadura sprouts and ripens slowly—as such, it is sensitive to altitude. It is grown mainly in valleys and slopes which are suitably orientated to maximize sunlight. It blends well with other local varieties like Godello, and as a stand-alone, makes an aromatic, refreshing wine with peach, apricot and citrus notes behind a floral background.

•7• Coto de Gomariz, 2020 Ribeiro Blanco ($26)

•7• Coto de Gomariz, 2020 Ribeiro Blanco ($26)

A blend of four different varieties; Treixadura (70%) with the rest an even split of other native Galician grapes, Godello, Loureiro and Albariño. The grapes come from vines cultivated using the Fukuoka theory of agriculture, which Ricardo Carreiro believes allows different soils (granite sands, clay and schist) to reveal their true personalities. It is a mineral-driven wine with citrus and ginger on the nose, while on the palate, orange zest, lemon pith and bitter quince appear.

Sílice Viticultores

Founded in 2013 by brothers Carlos and Juan Rodríguez and Galician/Swiss winemaker Fredi Torres, Sílice Viticultores is—as the name suggests—organized around the winegrowers of Ribeira Sacra, whose vertiginous slopes lining the Sil River Canyon is the lifeblood of the project. Silice currently works with a total of 20 acres of vines (four of which belongs to Juan and Carlos) planted primarily on granite, with some schist and gneiss parcels in the zones of Amandi, Doade, and Rosende. All of the vineyards are farmed organically, with copper and sulfur treatments applied only as needed.

Juan and Carlos Rodríguez with Winemaker Fredi Torres, Sílice

Says Carlos Rodríguez, “Our lineup of small-to-tiny-production wines are racy, fresh, and fun, yet seriously elegant, with razor-sharp detail, with structure to age. Sílice farming and winemaking prioritizes the bright, Atlantic fruit character of the region, and the expression of individual parcels and zones without sacrificing the fierce natural energy of the region or its favored red grape, Mencía. Choosing the perfect moment of harvest, fermenting multiple red and white varieties together with strategic use of stems, cold macerations, and gentle extraction guarantee exciting snapshots of place and vintage every year.”

The Rodríguez brothers are from the hamlet of Barantes de Arriba, in the municipality of Sober (Lugo province), prime Ribeira Sacra winegrowing territory on the north bank of the River Sil.

Mencía