Fanfare For The Uncommon Grape: Visionary Spanish Producers Explore The Capabilities of 23 Heritage Varieties’ and Demonstrate Their Potential For Complexity. A Dozen: 7 Red, 4 White & 1 Rosé $296

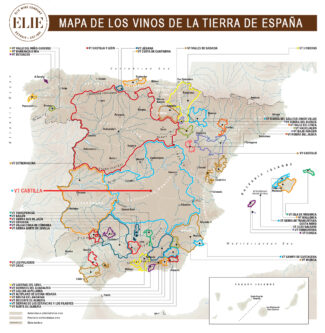

The wine world’s equivalent to the dinosaur-destroying Chicxulub meteor is a microscopic louse called phylloxera. By the end of the nineteenth century, the bug had killed most of the vines in Europe, and when they were replanted (often using louse-resistant American rootstock) the focus tended to be on resilient varieties capable of producing the most fruit. This was a desperation move; a means of recouping losses and ensuring that the industry could survive. Today, of the ten thousand grape varieties, only 13 of them occupy more than a third of the world’s total vineyard surface.

Wines of the Future That Look to the Past

In Spain, nostalgia and commerce have joined hands to resurrect a number of heirloom grapes, some of which were all but extinct and only found in a few isolated back-country pockets. This week’s package will echo Victor Frankenstein’s cry of delight “It’s alive!” by showcasing the second incarnation of many indigenous Spanish grapes. It is not only a historical cornucopia, but a collection of tastes and flavors that have nearly been forgotten.

Keep in mind, these grapes are the scrappers—tough little fighters who have made it into the twenty-first century despite the odds. As such, they are looked to as a window to the future, when climate change is making conventional grapes less comfortable with their terroir. Learn to pronounce the names below, because you may find it necessary to speak them aloud in the years to come.

The Quest to Recover Heirloom Varieties

Miguel Torres Maczassek, president of the extensive Cataluyan winery Familia Torres, describes his father’s mission to revive varieties that survived the phylloxera crisis: “There were once many more varieties than the ones that we know today. But the vineyard infestation, which nearly decimated an entire industry, also created a reckoning. Post-phylloxera, winemakers cultivated varieties guaranteed to do well in the climate, or turned toward more fashionable grapes that held international appeal. My father’s project was philanthropic project. In his mind, it was not only to make a wine, but to have a botanical collection.”

Other Spanish bodegas have taken up a similar challenge, and the overall lesson learned? It isn’t as easy as it sounds. Once a vine has been designated an ‘ancestral variety’, the hard work begins: Vines of that age are riddled with disease, and the viticulturists need pristine plant material for further experiments. So the vine must be reproduced multiple times in a greenhouse using new cells over several growth cycles until it’s given a clean bill of health.

And even then it takes time to understand a heritage vine’s individual nature, requiring several harvests. Like all grapes, terroir plays an irreplaceable role in finding the ideal site to bring out desired qualities, and finding this happy place may also take many vintages. And even then, the vine must reach the level of maturity required to produce acceptable wine.

On average, therefore, it is 14 years between the discovery of a heritage varieties and the time it is viable for winemaking.

“It’s been surprising that we find varieties that we need so much today,” concludes Torres Maczassek: “Here in the Penedès with the climate change, with the heat and the lack of rain, we are finding varieties that ripen late that have good acidity—this is a gift that came from nature. I cannot ask for more. These are the varieties that probably our children will use.”

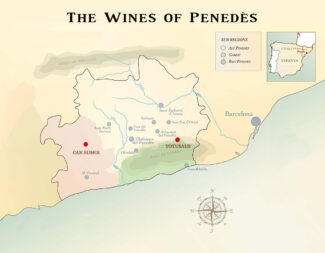

Catalunya

When Wine Becomes Crucial to Cultural Identity

The Catalan provinces of Barcelona, Tarragona, Lleida and Girona remain a part of Spain, but if you ask the residents, four of five of them will tell you they shouldn’t be. One of the most fiercely independent territories in the world, Catalunya is designated as a nationality by its Statute of Autonomy, and this is based on language, culture and administrative/political motivations.

And of course, wine.

As Catalan worldview differs from those of their Castilian, Galician and Andalusian countrymen, Catalan wine has little in common with those from the rest of Spain. There are ten denominated wine regions that focus mostly on familiar Mediterranean grape varieties, primarily Grenache and Carignan (also called Carinyena or Samsó) among red grapes, as well as Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah and Trepat. White varieties Parellada, Xarel-lo and Macabeo (called Viura in Rioja) that are primarily used for the production of Cava, the region’s premier sparkling wine and perhaps the most universally loved—and representative—of Spanish wines.

Tutusaus

Based at Can Tutusaus, in the center of the remote village of Olesa de Bonesvalls in the Garraf Natural Park, Tutusaus has become a pet project of husband Raimon Badell and wife Anna, whose award-winning Cava is proudly featured on the shelves here at Elie’s. As a team, Raimon and Anna have replanted ancient terraces in a rocky landscape otherwise dominated by pine trees interspersed with glimpses of the Mediterranean Sea. The oldest vines at Tutusaus were planted by Raimon’s father during a last-century’s craze for international grape varieties, and the Merlot remains an outstanding Spanish example of this variety.

The estate and its surrounding pine groves has stood since 1348, but it was only in 1729 that the country house was rebuilt within the village of Olesa, where the cellar is presently situated. The property comprises several acres of olive groves—resuscitated after years of neglect—and about thirty acres of vines. The rest is a maze of pine and oak forests, dwarf shrubs, brooms, fennel, rosemary, thyme, lavender and dwarf palms.

Raimon Badell, Tutusaus

In 1987, seduced by this mysterious land, Joan Badell bottled his first wines and planted his first trained vines. In 1999, his son Raimon, who was then studying oenology, became a close collaborator and opted to turn the estate toward ecological and biodynamic agriculture.

“Bottling the land,” is the way that Raimon Badell describes his interpretation of winemaking. “We only work with grapes picked from this estate,” says Rai, “where vines are situated between 800 and 1500 feet above sea level, bordering the Natural Park of the Massif of Garraf. The vineyards grow on hills with calcareous-clay soil and produce where the climate is distinctly Mediterranean, strongly influenced by the vicinity of the sea.”

Marselan

Marselan is a red French wine grape, a cross between Cabernet Sauvignon and Grenache. It is a niche variety, and not one of the rescued orphan grapes that survived phylloxera—it was first bred in 1961 by Paul Truel near the French town of Marseillan from which it takes its name. Wines made from Marselan tend to be medium-bodied with fine tannins, good color and display characteristic notes of cherry and cassis.

•1• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2021 Penedès Red ‘Marselan’ ($18)

•1• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2021 Penedès Red ‘Marselan’ ($18)

Although Marselan is frequently used as a base wine for blends, this is 100% Marselan hand-harvested from Badell’s estate in Alt Penedès, located entirely with the national protected area of the Massís del Garraf. The grapes are pressed and fermented in temperature-controlled, stainless steel 3,000-liter vats, then aged for 3 months before bottling. It shows the exuberant fruit-centered ripeness of Grenache and the elegant structure of Cabernet Sauvignon.

•2• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2022 Penedès Rose ($18)

•2• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2022 Penedès Rose ($18)

100% Marselan Rosé. The grapes are pressed and left in contact with the skins for several hours and fermented for 17 days in temperature-controlled, stainless steel 3,000-liter vats. The wine shows a springtime bouquet of young strawberries, raspberries and touch of minerality.

Xarel-lo

All the exotic mysteries of Catalunya may be contained within a single word, Xarel-lo, which in its correct spelling contains a diacritic scarcely known outside the region—a small dot where we have placed a dash. It’s called a ‘punt volat’—a flying point, and indicates a glottal pause. The pronunciation, somewhere in the neighborhood of ‘shah (or ‘chah)-REL-LO’ introduces you to the most aromatic of the Cava trinity; it also makes a heady, hallowed still wine that ranks among Spain’s finest whites. Not only is it delicious, the grape is rich in polyphenols and high in the antioxidant resveratrol, often associated with red grapes and the mystery behind the formerly ballyhooed ‘French Paradox.’

•3• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2021 Penedès White ‘Xarl-lo’ ($18)

•3• Tutusaus ‘Ona’, 2021 Penedès White ‘Xarl-lo’ ($18)

The grapes for this 100% Xarel-lo are hand harvested from Raimon Badell’s estate in Alt Penedès, which is located entirely with the national protected area of the Massís del Garraf. The grapes are pressed and fermented in temperature-controlled, stainless steel 3,000-liter vats, then aged in contact with fine lees for a period of 3 months before bottling. The wine shows straw yellow; the aroma filled with citrus, peach, flowers and herbs that follows through the delicate fruity taste and soft tannins in a long finish.

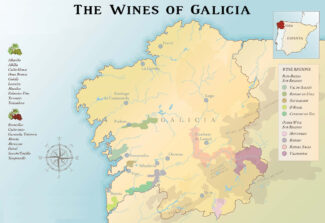

Galicia

Farming With Care and Sensitivity, Experimenting With Different Methods of Winemaking

Occupying the northwest corner of the Iberian Peninsula and exposed on two sides to the Atlantic Ocean, Galician wines are shaped by winds and waves. Best known for its Rías Baixas, a crisp, slightly fizzy and aromatic wine made predominantly from Albariño, there is a two-way stylistic influence with Minho (particularly Vinho Verde), just across the border in Portugal.

Over the past few decades, winemakers in Galicia have become increasingly aware of the potential of their prize grape, and locals have discovered that Albariño bears a striking resemblance to Riesling in the purity of its aroma and surprising its ability to age in bottle. Experimentation has been rife, including barrel-aging and judiciously applied malolactic fermentation to scale back the acidity.

Coto de Gomariz

Coto de Gomariz is located in an ideal winegrowing zone near the eastern edge of Galicia, where the slopes overlook the Avia River. The 66 acres were the brainchild of Ricardo Carreiro, who makes the most of the unique microclimate (schist, granite and sandy soils) through a cornucopia of local wine varieties including Treixadura, Godello, Loureira and Albariño. At the turn of this century, Carreiro upgraded the entire estate with integrated architecture and modern installations that allow for the annual production of nearly 200,000 bottles of wine.

Ricardo Carreiro, middle, and team, Coto de Gomariz

Sousón

Largely unknown outside Galicia, Sousón is the most widely-planted red grape in Rías Baixas, and is genetically identical to Loureira Tinta. It is a late-budding variety that matures slowly, so it well suited to warmer areas and south-facing plots. Because of longer hang times, Sousón can reach high levels of alcohol, between 12.5 and 14 degrees, with enough acidity to permit extended barrel aging. As a rule, Sousón showcases dark fruits (blackberries and currants) and is often used as a blending grape, although the experiment-prone wine Galician winemakers are increasingly using it as a stand-alone variety.

•4• Gomariz ‘Flower and the Bee – Souson’, 2020 Ribeiro ($21)

•4• Gomariz ‘Flower and the Bee – Souson’, 2020 Ribeiro ($21)

Wine begins with a flower and a bee, and so strongly is this fact imprinted on the folks at Coto de Gomariz that in 2013 they changed their name to ‘A Flor e a Abella’. This 100% Sousón is made from the youngest vines within the Gomariz parish and grown on soil that is predominantly sandy. Cherry red with a violet rim, the wine brims with aromas of forest berries with a savory yeasty undertone.

Ferrol & Caiño

Ferrol, also called ‘Ferron’, is a rich red native Galician grape that is often used to bring aroma and structure to blends. It’s a vigorous variety, naturally resistant to mildew and botrytis, and based on the exposure of the vines, it may retain a bracing level of acidity after fermentation.

Caiño is a grape not found outside Galicia and Portugal’s Minho. It is known for making acid-driven red wines that rarely exceed medium body weight. However, the grape has thick skins and high tannins, leading many winemakers to vinify it using the carbonic maceration technique favored in Beaujolais.

•5• Wish ‘Viño de Encostas Xose-Lois Sebio’, 2018 Galicia ($45)

•5• Wish ‘Viño de Encostas Xose-Lois Sebio’, 2018 Galicia ($45)

‘Viños de Encostas’ is a personal project of highly-esteemed winemaker Xosé Lois Sebio, formerly of Coto de Gomariz. It consists of small-lot wines coming from northwest Spain. Meaning, ‘Wines of the Hills,’ Viños de Encostas features only the top fruit of each region that Sebio has planted or works closely with in hilly and steeper zones. ‘Wish’ is a field-blend of native varietals fermented in open vats; it undergoes malolactic to temper the acidity and rests for 18 months is used oak barrels. The resulting wine is silky and bright with lilac notes behind blueberry and cherry.

Albariño

Albariño is almost a synonym for Rías Baixas, where it makes up 90% of the plantings. It has traditionally been viewed as a fresh, aromatic, hardy variety that makes light, peach-tinted wines, although thanks to the introspection of a handful of Spanish winemakers, it is now seen to be a wine capable of a remarkable maturation within the bottle.

Ultra-modern styles of Albariño are richer and more textural, having been aged on their lees and given some time in to add complexity and a touch of creaminess.

•6• Coto de Gomariz ‘X’, 2021 Ribeiro ($30)

•6• Coto de Gomariz ‘X’, 2021 Ribeiro ($30)

95% Albariño, 5% Treixadura from two unique plots—‘As Penelas’ with schist soils (in Gomariz) and from ‘O Taboleiro’ with sandy granite soils. This wine originates far from the influence of the sea, resulting in a much more mature and complex wine than those of coastal Rías Baixas. The ‘X’ is a nod to the Gallego word ‘xisto’, or ‘schist’—the granitic soil that is characteristic of this region.

Treixadura

Called ‘the Jewel of Ribeiro’, Treixadura sprouts and ripens slowly—as such, it is sensitive to altitude. It is grown mainly in valleys and slopes which are suitably orientated to maximize sunlight. It blends well with other local varieties like Godello, and as a stand-alone, makes an aromatic, refreshing wine with peach, apricot and citrus notes behind a floral background.

•7• Coto de Gomariz, 2020 Ribeiro Blanco ($26)

•7• Coto de Gomariz, 2020 Ribeiro Blanco ($26)

A blend of four different varieties; Treixadura (70%) with the rest an even split of other native Galician grapes, Godello, Loureiro and Albariño. The grapes come from vines cultivated using the Fukuoka theory of agriculture, which Ricardo Carreiro believes allows different soils (granite sands, clay and schist) to reveal their true personalities. It is a mineral-driven wine with citrus and ginger on the nose, while on the palate, orange zest, lemon pith and bitter quince appear.

Sílice Viticultores

Founded in 2013 by brothers Carlos and Juan Rodríguez and Galician/Swiss winemaker Fredi Torres, Sílice Viticultores is—as the name suggests—organized around the winegrowers of Ribeira Sacra, whose vertiginous slopes lining the Sil River Canyon is the lifeblood of the project. Silice currently works with a total of 20 acres of vines (four of which belongs to Juan and Carlos) planted primarily on granite, with some schist and gneiss parcels in the zones of Amandi, Doade, and Rosende. All of the vineyards are farmed organically, with copper and sulfur treatments applied only as needed.

Juan and Carlos Rodríguez with Winemaker Fredi Torres, Sílice

Says Carlos Rodríguez, “Our lineup of small-to-tiny-production wines are racy, fresh, and fun, yet seriously elegant, with razor-sharp detail, with structure to age. Sílice farming and winemaking prioritizes the bright, Atlantic fruit character of the region, and the expression of individual parcels and zones without sacrificing the fierce natural energy of the region or its favored red grape, Mencía. Choosing the perfect moment of harvest, fermenting multiple red and white varieties together with strategic use of stems, cold macerations, and gentle extraction guarantee exciting snapshots of place and vintage every year.”

The Rodríguez brothers are from the hamlet of Barantes de Arriba, in the municipality of Sober (Lugo province), prime Ribeira Sacra winegrowing territory on the north bank of the River Sil.

Mencía

Native to northwest Spain and once considered synonymous with the red wines of Bierzo, Mencía has enjoyed a revival in recent decades following years of producing light and astringent wines; today, dedicated winemakers are using the grape to produce beautifully structured wines, often by using carbonic maceration to accentuate the variety’s fruit characteristics and reduce the naturally heavy tannins.

•8• Sílice Viticultores ‘Sílice’, 2019 Galicia ‘Natural’ ($31)

•8• Sílice Viticultores ‘Sílice’, 2019 Galicia ‘Natural’ ($31)

A mix of old vines (50 years +) owned by Juan and Carlos and some purchased fruit; 80% Mencía with the remainder a mix of Garnacha Tintorera, Albarello, Brancellao and a variety of white grapes. Native yeast fermentation with 30% stems and 14 days maceration in concrete lagares, stainless steel and old foudre, then aged nine months on fine lees in a combination of foudre, concrete and stainless steel. A nice blend of earthiness and red fruit.

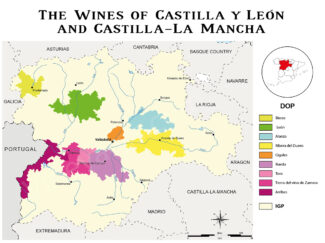

Castilla y León & Castilla-La Mancha

Terroir, Old Vines and Recovery

Castilla y Léon, in the northern half of the central Iberian Plateau, is the largest of Spain’s administrative regions, covering about one-fifth of the country’s total surface area. It stretches roughly 220 miles from the center of Spain almost all the way to the north coast. Equally wide, it connects Rioja to the border of Portugal. Tempranillo is unquestionably the wine king, known by various synonyms including Tinta del País, Tinto de Toro and Tinto Fino. It is the grape behind all of the region’s finest wines except Bierzo, which relies on Mencía.

Viticulture has shored up the region’s economy since Roman times, but it was not until the last part of the 20th century that the focus began to shift from quantity to quality. Producers like Vega Sicilia, Numanthia-Termes, Campo Eliseo and Bodega Palacios Remondo have spearheaded modernization and brought renewed interest to its wines.

Pardevalles Viñedos y Bodegas

Third generation vigneron Rafael Alonso is one of the pioneer winemakers of southern León. Viñedos y Bodegas Pardevalles, his family’s vineyards and 300 year old cellars are situated in northwestern Spain at around 2,400 feet in elevation where the uncommon and indigenous grape varieties Prieto Picudo (red) and Albarín Blanco (white) thrive in the extreme microclimate around the River Esla. Rocky soil, swinging diurnal temperatures and less than 20 inches of annual rainfall combine to create wines of superb ripeness, acidity and balance with highly developed aromatics.

Rafael Alonso, Pardevalles Viñedos y Bodegas

Granted official Denominación de Orígen status in 2007, León is nevertheless an ancient region that has been cultivating for wine production for centuries. The Alonso family holds around 95 acres there in the high plains, where Quaternary Period soils are covered in rounded stones that absorb the heat of the sun during the day. Similar to the galets roulés of Châteauneuf-du-Pape but at a much higher elevation, these stones help the vines bear the low nighttime temperatures and ensure a long, even ripening.

Prieto Picudo

One of the uncommon wine grapes in León, it produces deeply-colored red wines with clean acidity and high levels of sugar and tannin, a concentration that gives Prieto Picudo wines its unique character and taste. The shape of the fruit itself is also unusual; clusters are tight and the grapes are oval-shaped with a pronounced tip—hence the name of the variety: ‘prieto’ means ‘tight clusters’ and ‘picudo’ means ‘beak.’

Wines from this variety tend to be moderately tannic with good acidity and in this respect, are sometimes likened to Tempranillo. Typical flavors include redcurrant, blackberry and—like many León wines—licorice.

•9• Pardevalles ‘Gamonal’, 2020 León ($24)

•9• Pardevalles ‘Gamonal’, 2020 León ($24)

100% Prieto Picudo; the grapes for this wine originate from the ‘Pago El Gamonal’ vineyard. Hand-harvested Gamonal undergoes a cold maceration for four days followed by a fermentation with the skins in tapered stainless-steel vats. Malolactic also takes place in vats, after which the wine ages for a year in oak barrels, both French and American. The wine is juicy with brambly red berries, anise, black currant and a pure minerality that leans toward saline.

Albarín Blanco

A rare, light-skinned grape variety used in Castilla y León, Asturias and Galicia; despite the similarity in names, Albarín Blanco is genetically distinct from Albariño.

It is also aromatically similar to Albariño, but with a notable Gewürztraminer edge, showing ripe limes, lychee, mint, fig and orange. The variety almost disappeared, and when Rafael Alonso revived it, it was down to its last eight known vines.

•10• Pardevalles ‘Albarín Blanco’, 2022 León ($19)

•10• Pardevalles ‘Albarín Blanco’, 2022 León ($19)

Fresh aromas of herbs and citrus dominate this wine that also shows notes of white peach and some earthy qualities.

Bodega Almaroja

‘Almaroja’ means ‘red soul’ and winemaker Charlotte Allen, a British ex-pat living in Spain, says, “Red symbolizes vitality, courage, optimism, nonconformity and passion.” All of these attributes are integral to the soul of this iconoclastic woman and her deep love for the rugged terroirs of Zamora. She operates (for the most part) alone, adhering to the best of biodynamic practices, working on weaker parcels on specific dates and times, treating her vineyard for pest with botanical blends, including sage and nettle. She hand-harvests a scant half-ton per acre and grows a number of spectacular grapes little known outside her region.

Charlotte Allen, Bodega Almaroja

Juan Garcia

An indigenous grape in the Arribes known for its brilliant purple hue on the vine, which are often grown in bush style rather than trellised; wines made from unblended Juan García often are bright cherry red in color with violet rims and reflect notes of wild elderberry, pepper and minerals.

•11• Bodega Almaroja ‘Cielos y Besos’, 2019 Arribes ‘Natural’ ($22)

•11• Bodega Almaroja ‘Cielos y Besos’, 2019 Arribes ‘Natural’ ($22)

Made of blend that relies heavily on Juan García and Tempranillo from Charlotte’s ‘young’ vines which are fifty years old. Deep burgundy red with a violet rim, the wine elicits aromas of rustic wild berries, licorice and finishes with ripe tannins and stony minerals. 300 cases made.

Uva de Vida

“If we take care of the earth, we take care of ourselves,” says Uva de Vida owner Maria Carmen López Delgado. “Life has given me a new opportunity.” After recovering from serious illness, Delgado felt a spiritual connection to the natural world that convinced her to plant vineyards in the dry terrain of Castilla.

Carmen López Delgado, Uva de Vida

With her husband Luis Ruiz, she planted 25 acres of Graciano and eight of Tempranillo and set out to establish a farming philosophy that not only eschews artificial soil additives, but arranges vines in a complex geometric diagram to take advantage of the specific vibrations of energy found at 40˚ latitude. In addition, as the wine ferments and ages, music is piped into the cellar, because Delgado also believes in the power of sound vibrations to improve the health of her product.

Graciano

Graciano, also called Tinta Miúda, is a tough-skinned red grape variety that is particularly widespread in Spain and Sardinia (where it goes by the name Cagnulari). It’s also found in Southern France under the label Morrastel. It tends to be low-yielding, so even revived from near extinction, it is not widely planted, with fewer than 8000 acres planted globally compared to nearly 600,000 of Tempranillo, with which it is often blended.

It produces perfumed wine with considerably complexity on the nose and palate, with notes of ripe cherry and toast, accompanied by coffee, pencil lead, licorice, chocolate, and spice.

•12• Uva de Vida ‘Latitud 40’, 2018 La Tierra de Castilla ‘Natural’ ($24)

•12• Uva de Vida ‘Latitud 40’, 2018 La Tierra de Castilla ‘Natural’ ($24)

Uva de Vida winery sits at the wine-friendly 40˚ northern latitude, which circumvents the globe to include northern California, Sardinia and about half of the wine producing areas in China. Here, forty miles south of Madrid, it suits Graciano—the sole varietal used here. Although the ‘Vino de la Tierra de Castilla’ designation carries with it slightly less stringent regulations that the prestigious DOs of Castilla-La Mancha, like the ‘Super Tuscans’, gems may be found among the iconoclasts. Ideally served slightly chilled, ‘Latitud 40’ displays freshness on the nose with hints of lilac, menthol and pie cherries. On the palate, wild blueberries take center stage and the menthol shows a mint-leaf edge. The finish is long and juicy with a slight hint of chocolate. 20,000 bottles made.

RECENT ARRIVAL

Can Sumoi Bubbles With Joy:

Méthode Ancestrale’s Triumphant Return

At two thousand feet above sea level (in the Serra de l’Home range) Can Sumoi is the highest estate in the Penedès; Mallorca and the Ebro Delta are visible from the rooftop of the winery’s 350-year-old farmhouse. Below, vineyards sprawl across limestone-rich soil between stands of oak and white pine, which to the ecology-driven proprietor Pepe Raventós, share equal importance with the vines.

Pepe Raventós, Can Sumoi

“Forests,” he says, “protect the biodiversity of the estate; they are the green lungs of the world.”

The wines of Can Sumoi are also green insofar as they are produced using Certified Organic methods; vineyards are tended with natural compost, free of pesticides and with minimal intervention; a herd of sheep and goats is allowed to graze semi-freely among the vines. Certain esoteric biodynamic techniques may sound strange to laymen (such as timing vineyard activity to the phases of the moon) but to Raventós, they make perfect sense: “When the moon is ascendant, plant fluids concentrate more towards the roots of plants, and that’s when you want to do the pruning—so you don’t damage the plant.”

Once Raventós left D.O. Cava in 2012, he determined that his new property was ideal for producing sparkling wines in the ancestral style, made by bottling still-fermenting juice and allowing it to finish to dryness in bottle. In this method, carbon dioxide created during the finishing step gives the wine effervescence, while the spent yeast gives it a hazy cast. Some producers disgorge the bottles to purge the wine of this sediment, while others prefer to preserve its savoriness and texture.

Montònega

A pink-skinned grape variety grown in minute quantities in the Catalan region of Penedès. Here, vineyards are planted at altitudes of up to 2600 feet. For decades, Montònega has been losing ground to Parellada, the much more common variety to which it is genetically linked, mostly because of the low yields it produces. However, as a stand-alone, its grapes can result in wines that have superb structure and intensity. The aromatic profile of Montònega wines tends to be fresh and citrusy, albeit with aromatic, herbal and mineral, or saline, notes.

Can Sumoi ‘Ancestral Montònega’, 2021 Vi Mediterrani ‘Pur’ Brut Nature

Can Sumoi ‘Ancestral Montònega’, 2021 Vi Mediterrani ‘Pur’ Brut Nature

100% Montònega; this Pétillant-Naturel is made in the traditional method with no additives, stabilization or filtration. Harvested on September 15th in small bins it underwent primary fermentation with indigenous yeasts in stainless steel tanks for 24 days followed by 21 days in bottle. A balanced, fragrant and fresh sparkling wine filled with the aromas of ripe white fruit stand beside floral notes with fine effervescence and a slightly salty finish.

Notebook …

The Gesture of ‘Natural’: Wine in The Raw

In wine, ‘natural’ is a concept before it’s a style. It refers to a philosophy; an attitude. It may involve a regimen of rituals or it may be as simple as a gesture, but the goal, in nearly every case, is the purest expression of terroir that a winemaker, working within a given vineyard, can fashion. Not all natural wines are created equal, and some are clearly better than others, but of course, neither is every estate the same, nor every soil type, nor each individual vigneron’s ideology.

The theory is sound: To reveal the most honest nuances in a grape’s nature, especially when reared in a specific environment, the less intervention used, the better. If flaws arise in the final product—off-flavors, rogue, or ‘stuck’ fermentation (when nature takes its course), it may often be laid at the door of inexperience. Natural wine purists often claim that this technique is ancient and that making without preservatives is the historical precedent. That’s not entirely true, of course; using sulfites to kill bacteria or errant yeast strains dates to the 8th century BCE. What is fact, however, is that some ‘natural’ wines are wonderful and others are not, and that the most successful arise from an overall organoleptic perspective may be better called ‘low-intervention’ wine, or ‘raw’ wine—terminology now adopted by many vignerons and sommeliers.

At its most dogmatic and (arguably) most OCD, natural wines come from vineyards not sprayed with pesticides or herbicides, where the grapes are picked by hand and fermented with native years; they are fined via gravity and use no additives to preserve or shore up flavor, including sugar and sulfites. Winemakers who prefer to eliminate the very real risk of contaminating an entire harvest may use small amounts of sulfites to preserve and stabilize (10 to 35 parts per million) and in natural wine circles, this is generally considered an acceptable amount, especially if the estate maintains a biodynamic approach to vineyard management.

- - -

Posted on 2023.09.08 in La Tierra de Castilla, France, Spain DO, Penedes, Wine-Aid Packages, Catalunya, Cava, Arribes, Tierra de Leon, Ribeiro, Ribeira Sacra

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Aligote, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Cinsault, Clairette, Corvina, Counoise, Dolcetto, Erbamat, Ferrol, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Gamay, Garnacha, Garnacha Tintorera, Gewurztraminer, Graciano, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malbec, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marcelan, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montònega, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscat, Natural, Niellucciu, Parellada, Patrimonio, Pedro Ximénez, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Pouilly Fuisse, Pouilly Loche, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Riesling, Rondinella, Rose, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sagrantino, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Sciacarellu, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Search