The Whole Of The Sum And Its ‘Still’ Parts: Lelarge-Pugeot’s Coteaux-Champenois Premier Cru Vrigny in Red, Rosé & White + Single-Premier Cru Champagne Vrigny & Gueux Five-Bottle Pack (3 Coteaux-Champenois + 2 Champagne $359)

It’s a cosmic, back-to-the-future shift in thinking, and it is a change sweeping Champagne in both attitude and aesthetics. For the past fifty years or so, the editorial focus on sparkling wine has tended to focus on the cellar; blending regimens and methodology. However interesting these conversations are, most winemakers have never lost sight of the fact that their product draws its primary identity from the vine. And it this expression of terroir—an afterthought through much of the twentieth century—that has moved to the front of the bus in modern discussions of Champagne as a wine, it’s first and foremost obligation.

This week’s package consists of a five-bottle sampler from one of the Montagne de Reims most forward-looking producers, the ‘Two Dominiques’—winemakers and owners Dominique Lelarge and Dominique Pugeot—of Lelarge-Pugeot. These eighth-generation winemakers feature certified organic and biodynamic vineyards, making Meunier-focused wines from lesser known lieux-dits in somewhat obscure terroirs.

Champagne Tapestry: Blending The Parts For The Whole

As the emphasis on individual terroir begins to supplant homogeneity in Champagne talking points, it is no wonder that more attention is being placed on ‘vin clair’—still Champagne prior to the added bells and whistles of cellar work. Even when a final blend is the goal, Houses like Roederer will vinify plots individually. Says Chef de Cave Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, “I work with 410 individual parcels of vines and use 450 different vessels to ferment them. It creates a lot of work, because each of these wines is held in a separate tank until they are ready. But for me, it is vital that each plot is able to fully express its individual character.”

Blending is a Champagne paradigm; it was a blended wine even before it sparkled. Because of the cool, often inhospitable climate, combining batches from different villages and lots from other vintages was insurance against a poor harvest. Terroir, therefore, takes on a slightly different role here than it does in Burgundy, where climat blending is forbidden by law. In Champagne, an intricate tapestry is woven from villages—and vineyards—that produce still wine with contrasting, but ultimately harmonious personalities.

Far from diluting terroir, this method proves its value.

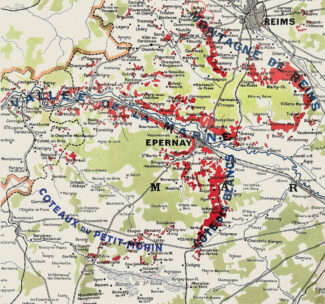

The Montagne de Reims, Grande & Petite: Variations Of Soil

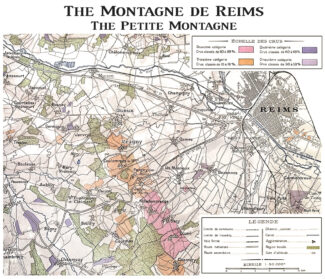

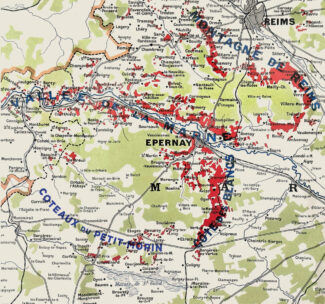

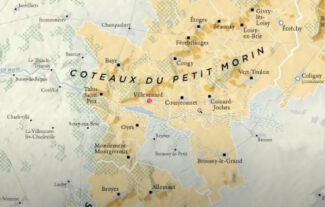

Located between Reims and Épernay, the Montagne de Reims is a relatively low-lying (under a thousand feet in elevation) plateau, mostly draped in thick forest. Vines find a suitable home on the flanks, forming a horseshoe that opens to the west.

So varied are the soils, topographies and microclimates here that it is not possible to speak of the region in any unified sense. Grande Montagne de Reims, which contains all of the region’s Grand Cru vineyards, covers the northern, eastern and southern slopes of the viticultural area, and Pinot Noir plantings dominate at 57%, followed by Chardonnay (30%) and Meunier (13%). Its vineyards face a multitude of directions, and soil type varies by village, giving rise to a breadth of Pinot Noir expressions, as well as exceptional Chardonnay.

To the west, the Grande Montagne de Reims gives way to the Petite, whose bedrock is chalk, but softer than the chalk found further south on the Côte des Blancs. This sort, called ‘tuffeau’, is an extremely porous, sand-rich, calcium carbonate rock similar to what is found in wine regions of the middle Loire Valley.

The Petite Montagne: The Primary Home of Meunier

In French, the word ‘petite’ often to refers to a ‘lesser’ commodity, but with La Petite Montagne, the reference is to elevation. This lower elevation means warmer weather, even in Champagne’s northerly climate, and in certain villages, the soils contain more sand, making it an ideal environment for growing Meunier.

Meunier accounts for approximately half of the plantings in the Petite Montagne, with Pinot Noir making up 35% and the rest Chardonnay. It is a growing conviction among growers of the modern era that Meunier is a Champagne grape whose time has come, especially as an age-worthy variety. Emmanuel Brochet of Villers-aux-Noeuds says, “People claim that Meunier ages too quickly, even faster than Chardonnay. I disagree. The curve of evolution is different. Meunier is quick to open and more approachable in youth, but then it becomes quite stable. Chardonnay tends to open later, but old Meunier remains very fresh and lively.”

Champagne & Domaine

Lelarge-Pugeot

‘Everything Starts in The Vineyard’

In 1985, when Dominique Lelarge took over his family estate, his first order of business was to improve the quality of the soil in the vineyard, and this began with a more sustainable farming approach. To this day, he views the use of pesticide an inherent threat to nature, and treats this understanding as a wake-up call: “Life is a gift from nature,” he says. “Everything starts in the vineyard, so it is important for us to respect what nature handed us.”

Lelarge-Pugeot

Although the Lelarge family has grown grapes in Vrigny since 1799, the last two decades have seen the leadership of the two Dominiques (winemakers and owners Dominique Lelarge and Dominique Pugeot) embrace and encourage diversity in both their ecosystem and in their outlook on Champagne production. Nestled in the Premier Cru village of Vrigny on the Montagne de Reims slopes—a mere 15 minutes west of Reims—their 21 acres are planted primarily to Meunier (11 acres), but a percentage of Pinot Noir (7 acres) and Chardonnay (3.4 acres) also figure into their blended wines.

Certified organic since 2014 and biodynamic since 2017 by Demeter, Lelarge-Pugeot encompasses 42 distinct parcels flourishing at elevations averaging 400 ft.

“We do not make wine so much as we farm vines, meticulously looking after every single step of the growth to produce the most natural Champagne possible.”

Soil Is Alive

To adopt a pesticide/herbicide free vineyard, certain concessions must be made. The beautiful thing is that they can be purely natural. When Dominique decided to stop the use of insecticides, he was able to reestablish the natural cycle of predatory wildlife in his vineyard, including ladybugs and lacewing larvae regulating spiders and caterpillars. In addition, he started growing grass between the vines for cover crop and to experiment new techniques in ploughing.

He says, “Most of this is common sense—a desire to let nature take its course—as well as a genuine concern for the next generations. We still relay on trace elements, sulfur and copper, to fight diseases. A horse ploughs our parcels in order to avoid soil compaction. We practice the green harvest, with all of the work taking place in the vineyard done meticulously and methodically.”

A third Dominique figures into the picture: “We attended a variety of classes by Dominique Massenot, who develops the Herody method to nurture the plant. Pierre Masson taught us biodynamic principles and Eric Petiot, aromatherapy, which uses of essential oils and plants to protect vines against disease. We have also started experimenting with some of our parcels in coordination with students from the Chamber of Commerce and the Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne.”

Premier Cru Vrigny

Exhibit A: The Evidence Of Things Vrigny

At its best, whether blended or not, Champagne expresses the site(s) upon which it is grown, and this is a wine fundamental that does not change because further processing adds carbonation. And it’s a fact that long before that carbonation is added, the still wine (vin clair), is evaluated at face value and many major houses isolate individual vineyards with specific characteristics at this point, the better to create a more complex and predictable final product.

Still Champagne, of course, released as a regional wine without effervescence, is the domain of a dedicated Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée: Coteaux Champenois.

If It’s Still Champagne, Is It Still Champagne?: Domaine Lelarge-Pugeot’s Premier Cru Coteaux-Champenois

Vrigny, in the northwestern part of the Montagne de Reims, is but one of a string of Champagne villages, and the last one to achieve Premier Cru status before the échelles des crus was retired. Of the 224 acres of vineyard, 71% is Meunier, 19% is Pinot Noir and 10% is Chardonnay divvied up between 40 exploitants, or vineyard owners.

1- Domaine Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Rouge de Meuniers’, 2015 Coteaux Champenois Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny ($70)

1- Domaine Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Rouge de Meuniers’, 2015 Coteaux Champenois Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny ($70)

A still, 100% vintage-dated Pinot Meunier of astonishing power, it showcases Meunier’s ability to weave together bold fruit, earthy aromas, and elegant minerality. From 40-year-old vines grown in chalk, limestone, clay loam and sand, it spends 20 months ‘en barrique’ before release.

2- Domaine Lelarge-Pugeot, 2020 Coteaux Champenois Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Meunier Rosé ($67)

2- Domaine Lelarge-Pugeot, 2020 Coteaux Champenois Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Meunier Rosé ($67)

A zero-zero Coteaux Champenois, the family’s first ever attempt at making a still rosé made exclusively with Meunier. The Meunier is from two parcels with tiny concentrated clusters, creating a highly aromatic wine (one of Meunier’s loveliest features) of high-toned pink grapefruit, watermelon, pomegranate and tarragon with the soil’s characteristic salinity.

3- Domaine Lelarge-Pugeot, 2020 Coteaux Champenois Montagne-de-Reims Premier-Cru Vrigny ‘La Côte des Glaises’ Blanc Chardonnay ($79)

3- Domaine Lelarge-Pugeot, 2020 Coteaux Champenois Montagne-de-Reims Premier-Cru Vrigny ‘La Côte des Glaises’ Blanc Chardonnay ($79)

Fewer than one thousand bottles of this rich, textured, experimental still wine made from 30-year-old Chardonnay vines grown on a historical lieu-dit parcel of clay (glaise) and loam in Vrigny. Another zero/zero wine vinified with native yeasts and no added sulfur or manipulation, it shows sweet white peach and nectarine with overtones of honeysuckle and almond.

Exhibit B: Perspective. He Said, She Said

Louis Pasteur is credited with having said, “There is more philosophy in a bottle of wine than in all the books in the world.”

Sensory experiences like taste, smell and mouthfeel, on which we wax poetically in wine descriptions, are all subjective sensations. It is a relative declaration; what we believe to be true may not be the same to everyone. When it comes to Champagne, philosophically speaking, ‘quality’ isn’t necessarily objectifiable nor a separable element, but that does not make discussions of our own perceptions of quality less valid. Yet, nearly all of us fall under the spell of magic that the beverage elicits.

Champagne is a mind sport; although in our notes we call out memory-triggers (like brioche and green apple), in fact, we do not pretend that they are separate components as would be the case, say, if you spread a warm brioche with green apple jelly. They are harmonious constituents that we recognize as ultimately unified within a whole. It is perhaps this unification of disparate but complimentary elements that make up the Champagne experience, and, in fact, of all gustatory exclamations.

Revealing Vrigny: Lelarge-Pugeot Single Premier-Cru Champagne

The following wines are built around Premier Cru Vrigny terroir which express their individuality while building to a whole that speaks to the nose, the tongue and ultimately, the mind.

4- Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot, Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Blanc-de-Blancs Extra-Brut ($66)

4- Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot, Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Blanc-de-Blancs Extra-Brut ($66)

Built from a blend of different Chardonnay parcels grown on sandy loam; 60% of the wine comes from the 2014 harvest and the rest from the reserve. The wine ages for six months in tank before bottling, then spends four years on the lees in bottle. The grapes from these parcels create a regal and precise expression of the terroir, full of floral aromas, ripe pear, peach and citrus notes complemented by a subtle twist of orange peel and dried fruit complexity. Disgorged September 2021.

5- Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Saignée de Meunier’, 2015 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Rosé Brut-Nature ($79)

5- Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Saignée de Meunier’, 2015 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Rosé Brut-Nature ($79)

100% Meunier from the 2015 harvest, drawn from 50 year old vines; saignée style, with 32 hours of skin contact and six months of barrel-aging followed by six years on the lees in the bottle. Zero dosage and no filtering. A fine bead and an elegant raspberry/salmon pink that suggests strawberries and Morello cherries on the nose, with an electric mouthfeel and a long, mineral-driven finish. Disgorged June 2021.

Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Tradition’, Harvest 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Brut ($66)

Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Tradition’, Harvest 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Brut ($66)

Lelarge-Pugeot’s entry-level, non-vintage Champagne from the 2018 harvest—a blend of 30 different plots in Vrigny. 50% Meunier, 40% Pinot Noir and 10% Chardonnay, the wine was aged for six months in tank before bottling, then spent three years on the lees. A nice textured wine behind notes of citrus, apricot, white toast and lime zest. Disgorged July 2022.

Trilogy: ‘Destination Moon’

As a child, I remember treasuring a Tintin cartoon where Hergé (Tintin’s Champagne-loving father), sent a bottle of Champagne (Brochet-Hervieux, now called Champagne Vincent Brochet) to the moon. It somehow seems fitting that the image captured by Dom Perignon’s famous exclamation, “I’m drinking stars,” found another outlet in the night sky. This celestial beverage has captured my imagination—and that of most of us—ever since.

Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot pays tribute to the moon throughout every lunar cycle; one of the components of biodynamics centers around applying holistic preparations and herbal teas based on the lunar calendar. With the trilogy of ‘Lùna’ wines from the Vrigny Premier Cru, Dominique Lelarge and Dominique Pugeot are paying their own homage to the power of the heavens.

Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Lùna Volume I’, 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Brut Nature ($144)

Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Lùna Volume I’, 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Brut Nature ($144)

An even split of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, the first of the moon trilogy is meant to be the culmination of the family’s work in biodynamics and continued experiments in natural vinification—indigenous yeast, zero added sulfur, only natural sugar. The vines are between 25 and fifty years old, grown on chalk, limestone, clay loam and sand. Vinification relies on spontaneous fermentation followed by six months of aging in tank or barrel before bottling, then three years on lees in the bottle. The wine shows generous notes of apple, brioche, almond and a precise minerality at the finish. Disgorged April 2022.

Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Lùna Volume II’, 2015 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Brut Nature ($144)

Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Lùna Volume II’, 2015 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Brut Nature ($144)

From the glittering 2015 vintage—notable for being the hottest season ever recorded in Champagne. Despite smaller than average yields, conditions were such that both Pinot Noir and Chardonnay excelled; ‘Lùna Volume II’ is an even split between the two varieties. The wine has a razor’s edge of acidity; it is crackling, bright and perfectly ripe with yellow citrus, crushed rocks, and notes of yeasty freshly-baked bread. Disgorged April 2022.

Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Lùna Volume III’, 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Rosé Brut Nature ($144)

Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Lùna Volume III’, 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Vrigny Rosé Brut Nature ($144)

85% Chardonnay and 15% Pinot Noir from a superb, sunny vintage where the crop was large and healthy, rich in sugar, with all varieties performing well. Volume III saw a short maceration and nine months of barrel-aging followed by three years on the lees, resulting in a wildly complex Champagne with aromas of candied strawberry and a long, rich mineral-driven finish. Disgorged April 2022.

Cru Gueux

The Village Next Door: Lelarge-Pugeot Site-Specific Cru Champagne

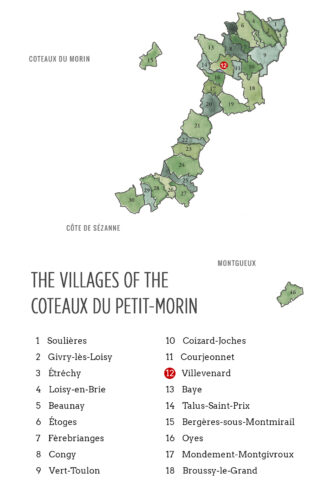

The commune of Gueux comprises about 2000 acres of gentle slopes in the northwestern portion of the Petite Montagne in the Montagne de Reims. 85% of the fifty planted acres is Meunier. The area remains somewhat obscure, but with its mix of sand, calcareous clay built around tiny marine fossils fifty million years old, it produces Champagnes that are remarkably terroir-centric, often showing saline notes and a spectacular tension on the palate.

Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Les Vignes de Gueux’, 2016 Montagne-de-Reims Cru Gueux Extra-Brut ($79)

Champagne Lelarge-Pugeot ‘Les Vignes de Gueux’, 2016 Montagne-de-Reims Cru Gueux Extra-Brut ($79)

75% Meunier, 20% Pinot Noir, 5% Chardonnay; Gueux is a short hop from Vrigny, the wine comes from two lieu-dit parcels: Le Linguet and Le Patenais. The former is a south-east facing plot of Pinot Noir planted on sandy soils in 2005, and the latter, an east-facing parcel of Meunier and four rows of Chardonnay on sandy loam and clay soils. Chardonnay was, in fact, a horticultural error dating back to 1965, but the grapes from these rows allow for even more complexity. Previously sold to négociants, the 2016 vintage shows aromas of preserved lemon, almonds and ginger tea with a laser-focused salinity on the finish. Disgorged June 2021.

Notebook …

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

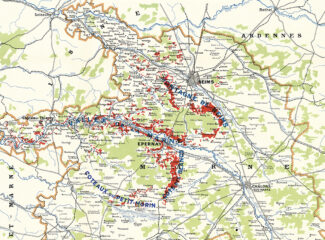

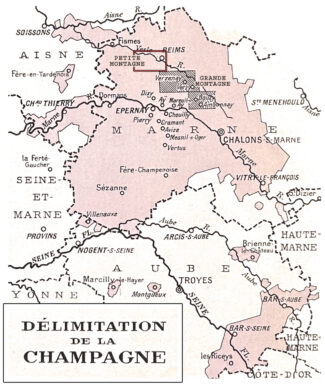

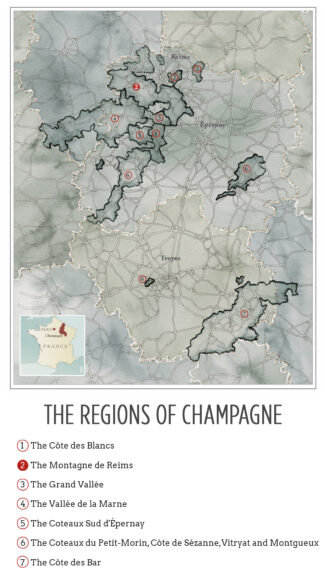

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

The lauded wine writer Peter Liem expands the number of sub-regions from four to seven, dividing the Vallée de la Marne into the Grand Vallée and the Vallée de la Marne; adding the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay and combining the disparate zones between the heart of Champagne and Côte de Bar into a single sub-zone.

Lying beyond even Liem’s overview is a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that compliment or contrast when final cuvées are created.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Épernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

- - -

Posted on 2023.11.10 in Coteaux Champenois, France, Champagne | Read more...

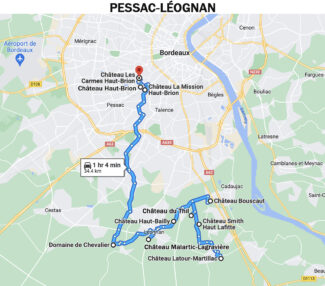

The Innate, Ageless Appeal Of Bordeaux’s Urban Appellation Pessac-Léognan Is Made Evident in Leading Ten Producers’ Wines + Half-a-Dozen Top Châteaux Second Wines $298

The focus on Pessac-Léognan is a nod to the increasing attention this appellation, (only 35 years old) is getting. The closest vineyards to Bordeaux city, Pessac-Léognan is not only capable of producing some of the world’s finest red wines, but unlike most of Bordeaux, it tends to be made with almost equal parts Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. It is also ground-zero for some of the best, age-worthy dry white wines in France, made from Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon.

A château’s ‘second’ wine has multiple raisons d’être; it may be a marketing tool to get a famous château name in front of consumers at a more affordable price, or it may be an outlet to bottle wines from grapes from younger vines and declassified lots—a system that undoubtedly serves to improve the quality of the Grand Vin. In any case, with the Bordelaise climate warming steadily, wines that were once regarded as cheaper afterthoughts have come into their own, as this week’s package (many of them ‘deep cuts’) sets out to prove.

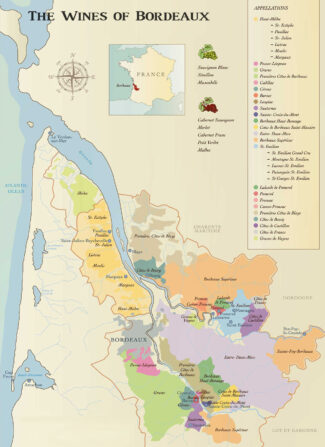

Land of Diversity: Bordeaux’s Landscape and Boundaries

Although Bordeaux is treated somewhat homogeneously by many who are simply dipping a toe into the waters of wine appreciation—thought of as the home of spectacular châteaux and exorbitantly priced Cab/Merlot blends represented by a few dominant names and families—the truth, as we know it, encompasses a lot more. Its sheer size relative to France’s other wine regions (Bordeaux has 300,000 acres of vineyards compared to Burgundy’s 74,000) guarantees a complex and varied environment capable of supporting an almost endless variety of styles and grape varieties.

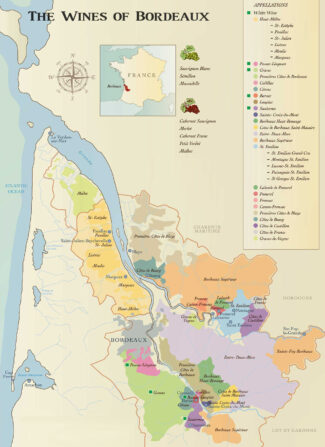

Referencing a map, Bordeaux follows the Gironde as it flows southwards from the Atlantic at Pointe de Grave towards the eponymous city. The Left Bank opens up to the appellations of Médoc and then, consecutively, Saint Estèphe, Pauillac, Saintt Julien, Listrac Médoc and Moulis-en-Médoc further inland, and Margaux—with Haut Médoc extending along half of the peninsula. At Margaux, the Gironde divides into two rivers: the Garonne flows north past the appellations of Pessac-Léognan, Cadillac, Graves, Cérons, Barsac, Loupiac, Sainte-Croix-du-Mont and Sauternes while the Dordogne heads west through Côtes de Bourg, Fronsac, Pomerol, Saint-Émilion and its ‘satellites’. In between these two rivers lies the Entre-deux-Mers, a region known for white wine. While the Left Bank of the Bordeaux wine map is home to countless extravagant châteaux, the Right Bank is generally considered more naturally beautiful with Saint-Émilion (despite its confusing classification system) and Pomerol drawing the most attraction.

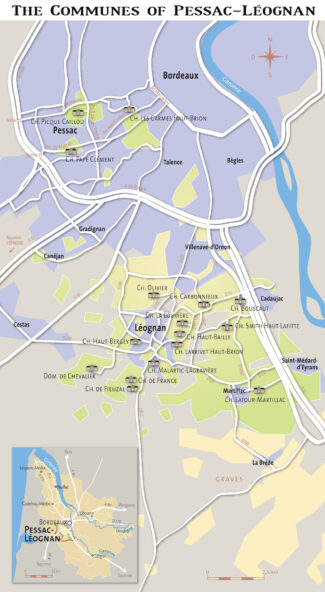

The Urban Appellation: The Birth Of Pessac-Léognan

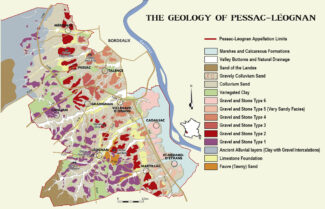

The same novice who may not grok the diversity of terroirs within Bordeaux may also admit that they are not familiar with Pessac-Léognan as a stand-alone appellation. This is understandable considering it has existed as such for only thirty-five years, although the soil beneath is the product of millions of years of geology that have deposited a harmonious mixture of ocher, white, red and pink quartz and quartzites, jaspers, flints and Lydians.

Extending over ten communes—Cadaujac, Canéjan, Gradignan, Léognan, Martillac, Mérignac, Pessac, Saint-Médard-d’Eyrans, Talence and Villenave-d’Ornon—the appellation decree was signed on September 9, 1987, marking the recognition of several unique qualities in a terroir that gave birth to the ‘New French Claret’ of Château Haut-Brion, one of the Grand Cru Classé estates in the famous 1855 valuation.

With the replanting of more than two thousand acres of vines, winegrowers have regained the Pessac-Léognan vineyard region that it had in 1935, resisting the urban expansion of the nearby city of Bordeaux.

Today, the total surface area exceeds 4000 of production, with vines and intensely urban landscapes co-existing.

The Originality of Pessac-Léognan Lies in Its Origin

That the area now specified as Pessac-Léognan is capable of producing world-class wines has been noted for centuries. The terroir is characterized by deposits of pebbles and gravel that has accumulated via the Garonne River for nearly two million years. The climate is regulated to the east by the river, which mitigates frost, and to the west by the forest, which protects vineyards from the prevailing winds and keeps the soil moist.

The key features of the appellation include a landscape of low rises that are sufficiently sloping to ensure good drainage, further facilitated by a network of small streams that act as natural drains feeding into the Garonne River; soils consisting of river gravel up to 25 feet deep are set on Tertiary limestone subsoil, both left behind by the river as it changed course during the Quaternary Era. These stones reflect the sun’s radiation, increasing the vines’ sun exposure and accelerating the ripening of the grapes—a combination of factors that represents Pessac-Léognan’s inimitable, inalienable heritage.

Grapes From Wrath: New Research Finds That Warm Summers and Wet Winters Yield Better Vintages in Southwest Bordeaux

Grappling with the pluses and minuses of climate change is a double serving of concern on the plate of every wine region on the planet; Pessac-Léognan is no exception.

First, what we all know to be true: Weather drives wine quality and taste. Temperature and precipitation occurring throughout the year—from bud break, while the grapes are growing and maturing, during harvesting, and even overwintering dormant vines—each play a role. The same vineyard can produce different quality levels in different years despite those wines coming from grapes grown on the same vines, on the same land, and being produced by the same methods.

With climate change upending many of the most predictable weather patterns (even among an otherwise random set of circumstances), a study done by Andrew Wood of the University of Oxford’s Department of Biology paired high-resolution climate data with annual wine critic scores from the Bordeaux wine region in southwest France from 1950 to 2020, and concluded that, “The trend, whether driven by the preferences of wine critics or the general population, is toward stronger wines that age for longer and give you richer, more intense flavor, higher sweetness, and lower acidity. And with climate change generally, we are seeing a trend across the world that with greater warming, wines are getting stronger.”

He adds: “With the predicted climates of the future, given that we are more likely to see these patterns of warmer weather and less rainfall during the summer and more rainfall during the winter, wines are likely to continue to get better. However, there is a tipping point; once water becomes more limited, if plants don’t have enough, they eventually fail. And when they fail, you lose everything.”

Pessac-Léognan’s ability to adapt and take advantage of this natural phenomenon is largely dependent on the commune in question, since each enjoys varying degrees of temperature modulation, allowing for differences in the levels of ripeness, alcohol, and picking dates. For example, Talence is warmer and there, the vineyards are picked earlier than Pessac, while Martillac harvests after Léognan. Overall, however, Pessac-Léognan is becoming increasingly warmer; 2022 saw the earliest start date for harvesting ever. 2022 was also the first vintage where some vintners requested and were able to irrigate select vines in various parcels due to the parching heat. Alice Leuret, Commercial director at Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion, indicates that irrigation permits required a mountain of paperwork, and at her estate, was restricted to five acres of young vines.

Six Top Châteaux Second Wines With a Six-Bottle Sampler Package ($298)

The tradition of ‘second’ Bordeaux wines predates Classified Growths by at least a century, and the innovation is credited to Château Margaux, who first released a wine labeled ‘2eme vin’ in the seventeenth century to indicate that the wine, while produced on the estate, came from vines considered unsuited for inclusion in the Grand Vin. In Pauillac, the first estate to make use of a second wine was Château Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande, who debuted La Réserve de la Comtesse in 1874.

These Six second wines represent a cross-section of how Pessac-Léognan has approached the concept. Although the appellation is fairly new, these estates are not.

Vintage 2020 in Pessac-Léognan: ‘Show Stoppers, Intensely Concentrated’

For Pessac-Léognan, the 2020 vintage was brilliant, with perhaps a touch more variance compared to other appellations. The growing season began with an unseasonably warm winter, which transitioned into a warm but humid spring. Although the warmth and humidity ensured the region was spared the worst of the spring frosts, endless rain settled in its place. The excess water and heat meant vine growth was rapid and producers had to be vigilant in managing both the vines and the spread of disease and rot. Unsurprisingly, the warm temperatures led to both an early budburst and flowering and the crop look set to be a large one. Summer brought sizzling temperatures and dry conditions, which ultimately led to concerns with drought. Both July and August were exceedingly dry and terroir became an important factor as to which vines had easy access to water reserves deep in the soil. However, the clear weather allowed for an early harvest in September with producers able to pick at their leisure. The resulting wines were generally brilliant as the grapes had been intensely concentrated by the drought-stricken summer and, as a result, were tiny and full of flavor.

Vintage 2019 in Pessac-Léognan: ‘Sophisticated, Very Pleasant Early Drinking’

The growing season began with a mild winter that evolved into a balmy spring. However, like much of Bordeaux, the region experienced a particularly icy April, which brought a significant risk of frost to the vineyards and producers had to be vigilant to protect the vines. The month also saw heavy rains, which helped hydrate the vines in preparation for what would transpire to be a very warm, dry summer. By mid-summer, the days were hot and arid; the nights, however, fortunately, remained cool, which helped preserve important acidity and aromatics in the grapes. July also brought two heavy rainstorms, which revitalized parched vines, leading to a fine harvest with above average quality.

Château La Mission Haut-Brion

First, the mothership: Among Château Haut-Brion’s more illustrious fans, Thomas Jefferson waxed poetic about the vineyard’s terroir, noting, “The soil of Haut-Brion, which I examined in great detail, is made up of sand, in which there is near as much round gravel or small stones and very little loam like the soils of the Médoc.” Jefferson went on to create his own classification of Bordeaux and listed Château Haut-Brion as one of the region’s top four vineyards, a status that would be echoed 75 years later in the official classification of 1855, when the château became the sole first growth located outside the Médoc.

In the modern era, the estate is in the hands of Prince Robert de Luxembourg who looks after the legacy with the expertise of the Delmas family. Both families are responsible for Château la Mission Haut-Brion, which is separated from Château Haut-Brion by the old Arcachon road and a set of train tracks. Under the management of Jean-Phillipe Delmas, both labels have actually improved in quality—remarkable for wines that had already garnered such hefty laurels.

1- Château Chapelle La Mission Haut-Brion ‘La Chapelle’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($108)

1- Château Chapelle La Mission Haut-Brion ‘La Chapelle’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($108)

The second wine from this great estate is built upon 50% Merlot, 46% Cabernet Sauvignon, and the balance, Cabernet Franc. It is full-bodied and round, expansive and powerful, yet flawlessly balanced with inherent delicacy of fruit expression. Textbook notes of sweet red and black currants, tobacco leaf, exotic spice, acacia flowers and lead pencil appear in the nose and carry through to the finish.

Château La Mission Haut-Brion, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($476)

Château La Mission Haut-Brion, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($476)

48.6% Merlot, 43.2% Cabernet Sauvignon, 8.2% Cabernet Franc; a touch of juniper enlivens an already lively palate filled with dark cherries, delicate hints of nougat, fresh orange zest and plums, showing silky tannins, finesse-rich acidity and salty minerality.

Château La Mission Haut-Brion, 2014 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($349)

Château La Mission Haut-Brion, 2014 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($349)

54% Merlot, 45% Cabernet Sauvignon, 1% Cabernet Franc; the wine offers an exquisite bouquet of pure black fruit, cold stone, a touch of black olive and a suggestion of boysenberry preserve. The tannins are deceptively fine, holding the structure very tightly, and having been given the decade of aging that such a wine requires, it is just beginning to drink at its optimum.

Domaine de Chevalier

Grapes may be the stock and trade of Pessac-Léognan, but as a land mass, it is mostly forest. Carved into a clearing in that forest, Domaine de Chevalier has been a mainstay of wine production in the region for hundreds of years. So much do the trees influence the wines that one of the first things Olivier Bernard did when he took over the estate (at the age of 23) in 1983 was to remove the sheltering belt that surrounded those acres most susceptible to frost.

At the time, the estate had only 44 acres of vines. Among Bernard’s other early decisions was to retain the winemaking team and enlarge the holding. In 1985, he purchased additional plots from neighboring vineyards; next, he began a long-term replanting program lasting from 1988 to 1995, including in this 17 acres of Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon.

Today, he is joined in daily operations by his two sons Adrien and Hugo. With 65 acres under vine, divisible into 90 individual plots, the potent Pessac-Léognan terroir is built around gravel with black sand over clay and hardpan soil. There are gentle slopes and elevations throughout the parcel which rise to around 200 feet, relatively high for Bordeaux.

2- Domaine de Chevalier ‘L’Esprit de Chevalier’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($36)

2- Domaine de Chevalier ‘L’Esprit de Chevalier’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($36)

50% Cabernet Sauvignon, 45% Merlot, 5% Petit Verdot; it sports a mix of bramble, mulling spice and savory notes steeped in smoky blackberry and cherry compote shores up by whiffs of loamy soil.

Domaine de Chevalier, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($117)

Domaine de Chevalier, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($117)

A blend of 65% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot, and 5% Petit Verdot aged iin just 35% new oak, it sports a dense purple hue as well as a quintessential Graves bouquet of cassis, earth, truffle, cold ash, tobacco and graphite. Balance is flawless and the finish is long and lush.

Domaine de Chevalier, 2016 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($299) 1.5 Liter

Domaine de Chevalier, 2016 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($299) 1.5 Liter

In 2016, spring was cool and flowering was a success; however the weather heated up over the summer with August becoming very hot and dry. The intense heat caused many of the grapes and vine foliage to suffer from heat stress and sunburn. September was dry until heavy rains fell at the end of the month and rot became a serious issue in October. Grapes picked early fared well, and are reaching peak drinkability now.

65% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot, 5% Petit Verdot displaying a sappy core of kirsch, raspberry pâté and plum reduction; it sits on a plush, focused and elegant bed of fine and powerful tannins, giving it plenty of aging potential still to be realized.

Château Haut-Bailly

At just under 75 acres, Haut-Bailly is a moderate-sized estate that produces about 80,000 bottles per year. The grapes line up in the vineyard in an order typical for Haut-Médoc, 60% Cabernet Sauvignon, 34% Merlot, 3% Cabernet franc and 3% Petit Verdot, although it is located in the commune of Léognan, which is usually more associated with white wine production. Since being purchased in 1998 by American banker Robert G. Wilmers, Bailly has steadily improved its output and now numbers in the upper echelon of Pessac-Léognan.

3- Château Haut-Bailly ‘Haut-Bailly II’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($45)

3- Château Haut-Bailly ‘Haut-Bailly II’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($45)

60% Merlot, 40% Cabernet Sauvignon; the second wine of Château Haut-Bailly is marked with freshness and fruit built upon a firm foundation. It shows a classic Graves scorched-earth character as well as pure red and black fruits, tobacco, and cedary herb-like aromas and flavors.

Château Haut-Bailly, 2014 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($117)

Château Haut-Bailly, 2014 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($117)

In 2014, the winter was extremely mild (the warmest in 10 years) but it also brought vast volumes of rain. January and February were particularly waterlogged, which created extremely humid conditions. However, despite the damp, bud break was both successful and far earlier than usual, kick starting the growing season. June delivered fantastic weather bar one devastating hailstorm, and some châteaux further north lost 80% of their crop. However, the summer quickly cooled with a damp July and an unusually chilly August. September saw a glorious Indian summer and temperatures soared, drying out the vines. A warm October gently eased the grapes to phenolic ripeness, rescuing the vintage. The harvest was leisurely and relaxed with many growers picking late to take advantage of the optimum weather.

The 2014 Haut-Bailly remains dark, sumptuous and expressive, exuding depth and finesse with ample resonance on the palate; big cassis and black cherry tinged with wood smoke, tobacco and licorice infusing a deep, creamy finish.

Château Smith Haut Lafitte

Rated as a red wine ‘Grand Cru Classé’ in the 1959 Classification of Graves, Château Smith Haut Lafitte sits on a low hill of pebbles and sand deposited by the Garonne River, offering grape vines not only superb drainage, but also reflected sunshine to lengthen the day’s ripening period. The estate is not to be confused with Château Lafite Rothschild (the Pauillac superstar) with which it has no connection, but both were named for their elevated physical status—‘la fite’ is an ancient dialectical word for hill.

4- Château Smith Haut Lafitte ‘Le Petit Smith Haut Lafitte’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($54)

4- Château Smith Haut Lafitte ‘Le Petit Smith Haut Lafitte’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($54)

Le Petit Smith Haut Lafitte is vinified at Smith Haut Lafitte, and from vineyard to cellar, the entire winemaking goes through the exact same process as the Grand Vin. A blend of 60% Cabernet Sauvignon and 40% Merlot, the grapes are sorted twice, before and after destemming. Then the berries go through optical sorting before being gently dropped uncrushed on both wooden and stainless-steel vats for fermentation. Aged for 14 months in barrels (20% new barrels) produced in their very own in-house cooperage; Le Petit Smith Haut Lafitte 2019 is extremely fine with silky tannins and beautiful notes of blackcurrant, licorice and dark chocolate, showing great finesse and structure to suggest a lot of aging potential.

Château Smith Haut Lafitte, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($169)

Château Smith Haut Lafitte, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($169)

59% Cabernet Sauvignon, 36% Merlot, 4% Cabernet Franc and 1% Petit Verdot aged for 18 months in French oak barrels, 60% of which are new. The wine shows a deep, opaque purple color with soaring aromas of blackberry, currant, blueberry and cherry combined with spicy aromas of clove, vanilla and cinnamon underpinned by a flinty note. Suave on the palate with mouth-coating tannins and soft, integrated acidity.

Château Smith Haut Lafitte, 2014 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($120)

Château Smith Haut Lafitte, 2014 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($120)

62% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot, 6% Cabernet Franc and 2% Petit Verdot; this remains a massive wine with focused black fruit, graphite and savory herbs—age has mellowed the intensity a bit, but even tamed, it retains the dusty and earthy flavors so typical of the Graves area.

Château Smith Haut Lafitte, 2005 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($259)

Château Smith Haut Lafitte, 2005 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($259)

The legendary 2005 vintage is the product of a hot, dry, growing season and from start to finish. While dry, there was just enough moisture at the right times to nourish the vines. Flowering took place at the beginning of June and during the late summer months, some vines had become stressed from the drought, but the rains which fell in August came at an ideal time, averting the potential for drought. Starting in late September and continuing into October, the days were sunny and warm, with chilly night temperatures. This allowed the grapes to be harvested under picture-perfect conditions and gave the growers the opportunity to wait until the fruit achieved ideal phenolic ripeness. The combination of warm days, cold nights and just enough rain at the right moments produced extraordinary 2005 Pessac-Léognans.

A gorgeous floral nose with notes of graphite, blueberries, blackberries and cassis introduce an inky, dense, yet strikingly pure wine that manages to remain delicate despite stunning concentration and multi-layered mouthfeel. It is drinking wonderfully, but will last considerably longer under the correct storage conditions.

Château Smith Haut Lafitte, 1998 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($279)

Château Smith Haut Lafitte, 1998 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($279)

In 1998, spring was cool and flowering was a success, however the weather heated up over the summer with August becoming very hot and dry. The intense heat caused many of the grapes and vine foliage to suffer from heat stress and sunburn. September was dry until heavy rains fell at the end of the month and rot became a serious issue in October, so harvest timing was critical. Much of Graves produced average-quality wines, but in Pessac-Léognan, some of the top estate produced truly impressive wines.

The nose of Château Smith Haut Lafitte 1998 remains precise, if mature, with espresso, smoke, licorice, truffle and dark red berry scents. Herbal notes play with the fruit—thyme especially—ending with black cherries, thyme and coffee notes.

Château Smith Haut Lafitte, 2016 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($480) 1.5 Liter

Château Smith Haut Lafitte, 2016 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($480) 1.5 Liter

65% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot, 4% Cabernet Franc and 1% Petit Verdot; the wine displays lush waves of cassis, cherry preserve and raspberry puree gliding through bramble, tar and notes of melted licorice. The finish features an intense echo of pastis and sweet tobacco and offers a latent grip.

Château Malartic-Lagravière

Originally Domaine de Lagravière, Château Malartic-Lagravière—situated on the finest gravel hilltop in Léognan—is one of only six estates in Bordeaux classified for both white and red wines. 100 acres are given over to red grape varieties (45% Cabernet Sauvignon, 45% Merlot, with 8% Cabernet Franc and 2% Petit Verdot) and 15 acres to whites (80% Sauvignon blanc and 20% Sémillon). The estate has belonged to the Bonnie family since 1997, originally with oenologists Michel Rolland (replaced by Eric Boissenot in 2020) and Athanase Fakorellis as consultants.

5- Château Malartic-Lagravière ‘La Réserve de Malartic’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($26)

5- Château Malartic-Lagravière ‘La Réserve de Malartic’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($26)

82.6% Merlot, 12.3% Cabernet Sauvignon, 5.1% Petit Verdot. Merlot-heavy, yet quite representative of the Malartic terroir in a second wine. It shows soft grilled caramel around the edges of plump black fruits, with beautiful extraction and great freshness throughout the palate, with currant and chocolate through to the end.

Château Malartic-Lagravière, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($68)

Château Malartic-Lagravière, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($68)

55.9% Cabernet Sauvignon, 41.3% Merlot, 2.8% Cabernet Franc. A wine with a particularly lovely bouquet, almost disarming with the intensity of its blackberry, briar and subtle marine scents—a whiff of brine in the background from the distant Gironde estuary. The palate shows extremely fine tannins that frame layers of raspberry and orange rind with a dab of white pepper on the afterglow.

Château Malartic-Lagravière, 2014 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($80)

Château Malartic-Lagravière, 2014 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($80)

In 2014, The winter was extremely mild (the warmest in 10 years) but it also brought vast volumes of rain. January and February were particularly waterlogged, which created extremely humid conditions. However, despite the damp, bud break was both successful and far earlier than usual, kick starting the growing season. June delivered fantastic weather bar one devastating hailstorm, and some châteaux further north lost 80% of their crop. However, the summer quickly cooled with a damp July and an unusually chilly August. September saw a glorious Indian summer and temperatures soared, drying out the vines. A warm October gently eased the grapes to phenolic ripeness, rescuing the vintage. The harvest was leisurely and relaxed with many growers picking late to take advantage of the optimum weather.

52% Cabernet Sauvignon, 40% Merlot, 5% Cabernet Franc and 3% Petit Verdot brought up in 70% new oak. It shows a high-toned, upfront bouquet with kirsch, crushed strawberry, iodine and iris scents and a palate is rounded on the entry with supple tannin and impressive depth leading to a subtle white pepper/sage note towards the finish.

Château Malartic-Lagravière, 2010 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($160)

Château Malartic-Lagravière, 2010 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($160)

The 2010 vintage for Bordeaux is recognized as legendary across the board, but Pessac-Léognan in particular delivered outstanding selections. A cold winter delayed the initial vine growth, which slowed and disrupted both budburst and flowering. There were persistent problems with both millerandage and coulure, particularly among Merlot, which further cut yields. Despite a wet June giving a damp start to summer, the season soon heated up turning exceedingly hot and dry, offering the vines a nice amount of stress to concentrate flavors. the long growing season allowed the grapes to reach phenolic ripeness resulting in a highly successful vintage.

Château Malartic-Lagravière 2010 remains ripe-tasting, with edges of leather, dark polished fruit and perfumed dried flowers. The mouthfeel boasts soft silky tannins and a beautiful texture with all the structure and density of the vintage, packed with plum and black currant fruits. The acidity is almost sweet in its richness, blending easily into the dark fruit.

Château Malartic-Lagravière, 2000 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($220)

Château Malartic-Lagravière, 2000 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($220)

In 2000, the winter was mild but a warm, wet spring created a fleeting problem with mildew. However, from July onwards, a spectacular summer dominated with hardly any rain until mid-September when the heavens opened, although it was likely welcome in some areas. Sunny weather then returned for the October harvest only broken by a single day of rain, a boon to parched vines.

Big charry toasted oak shows on the nose with a deep core of cassis; on the palate Château Malartic-Lagravière, 2000 is concentrated and quite rich, with spice and pepper elements over sweet, glossy black fruits. The tannins were rich from the outset and served the wine well over the decades.

Château Carbonnieux

This is an estate with which even a casual wine drinker is probably familiar: With more than 420 acres under vine, it is easily the largest vineyard in Pessac-Léognan, and one of the largest in Bordeaux. Its wines are widely available in the United States.

In 2011, the property embarked on an extensive renovation that would allow it to vinify on a parcel-by-parcel basis. Added were temperature-controlled, stainless steel vats in a myriad of sizes (ranging from 150 hectoliters to 250 hectoliters). The whites of Chateau Carbonnieux are vinified in 25% new, French oak barrels where malolactic also takes place, as done aging for an average of 10 months before bottling.

6- Château Tour Léognan, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($29)

6- Château Tour Léognan, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($29)

Originally a distinct estate located adjacent to Château Carbonnieux, both properties were purchased by Marc Perrin in 1956. Perrin reorganized the vineyards of both and designated Tour Léognan as the second wine of Carbonnieux. According to the winery, Château Tour Léognan is made from the younger vineyards of Château Carbonnieux (vine younger than 12 years of age). It follows the same process and deserves the same care as its bigger brother. Being drier and fruitier, the Château Tour Léognan wines can be served younger but they still reflect the rich mineral variety of the soils, so specific to the appellation.

2020 reflects the lean, sleek and focused profile of the Grand Vin, with blackberry fruit, gravel and unsweetened chocolate scents held in wonderful equilibrium. The stony middle is fruit filled, rich, poised and elegant but unfolds into a strong finish laced with mineral.

Château Carbonnieux, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($49)

Château Carbonnieux, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($49)

49% Cabernet Sauvignon, 45% Merlot, 4% Petit Verdot, 2% Cabernet Franc. Among the finest vintages yet produced by the estate, the nose, with its smoke, flowers, cocoa, and wet earth scents, is a standout. But on the palate, within layers of lush, silky, blackberries, plums and cocoa, the wine comes into its own as soft, supple, long and complex.

Château Latour-Martillac

The iconic tower standing at the gateway of Château Latour-Martillac (for which the property is named) is all that remains of a fortified medieval castle. began in the early 1940s when the estate was expanded in size, especially with land devoted to red wine grapes. Prior to this, close to 75% of the estate was devoted solely to the production of white wine—it was one of only six properties in Graves classified for both red and white wines. In 1955 Jean Kressman became the owner of Latour-Martillac, although he had managed it since 1940. Today, two of his sons, Tristan and Loïc, manage the château.

Château Latour-Martillac, 2016 Pessac Léognan Rouge ($75)

Château Latour-Martillac, 2016 Pessac Léognan Rouge ($75)

The wine is 60% Cabernet Sauvignon, 32% Merlot and 8% Petit Verdot, rather solid, with a juicy yet restrained core of dark currant and blackberry compote flavors that has unwound nicely over the years. It is embedded with a brambly grip and shows dried tobacco leaf, anise and tar notes through the finish.

Château Bouscaut

Owned by the Lucien Lurton family for 43 years, Château Bouscaut is managed today by Sophie Lurton and husband Laurent Cogombles as well as their son, Armand Cogombles.

The property—although large—consists of a single parcel of vines growing on a sloping hillside of gravel, clay and limestone.

After receiving HVE3 certification in 2018, Chateau Bouscaut began converting to 100% organic farming and were officially certified as organic with the 2023 vintage.

Château Bouscaut, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($48)

Château Bouscaut, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($48)

61% Merlot, 33% Cabernet Sauvignon, 6% Malbec: A classic Pessac-Léognan nose of pure cassis and black raspberries interwoven with notes of violets, tobacco, sous bois and ample spicy background oak enhanced, no doubt, by the Malbec. A beautifully balanced wine that will benefit from 4-5 years of bottle age and keep for 15-20 years or longer.

Château le Thil Comte Clary

Owned by Florence and Daniel Cathiard, Le Thil is located in the heart of Pessac and surrounded by the well-known estates of Châteaux Carbonnieux and Smith Haut Lafitte; Lafitte is also owned by the Cathiards. The vineyards are predominantly Merlot, planted on a superb clay-limestone slope facing due south while some Cabernet Franc is planted on the plateau portion of the estate.

Says Daniel Cathiard: “We make wine according to a unique philosophy: Bio-Précision. We are in the second year of our Organic Agriculture certification, and have added such positive-energy improvements as a CO2 recycling system into baking soda. Grapes are sorted twice, before and after destemming, and are not pressed before undergoing fermentation in vats. Tannins and color are extracted by soft punching down and a few pumping overs, then aged 14 months in barrels (30% new). Perhaps best of all, these barrels are produced in our in-house cooperage.”

Château le Thil Comte Clary, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($41)

Château le Thil Comte Clary, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($41)

Wild cherry, tobacco, cedar, mint and white pepper lend notable freshness to this 2020 blend, which hails from clay-limestone slopes with southern exposure, unusual for the appellation, more typical of Saint Émilion than Pessac-Léognan. Vinification of the red takes place in temperature controlled stainless steel tanks with a 28-day maceration and is. Château Le Thil is aged for 18 months in 50% new oak barrels. The wine offers a punch of spicy Damson plum and red cherry on the opening, melting into tobacco, cedar, mint and white pepper with solid acids and lifted floral accents through the finish.

A Star Reborn:

Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion

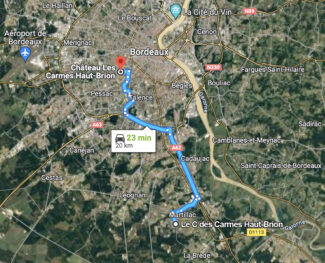

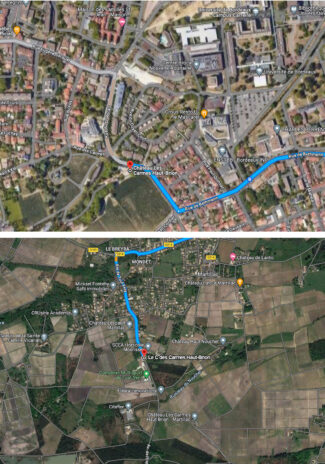

Named after a group of friars who managed the estate from 1584 until the French Revolution in 1789 (and of course, for Château Haut-Brion), Les Carmes originated as a windmill and the surrounding land gifted by Jean de Pontac of Haut-Brion. When it was sold in 2010 for €1.54 million per acre, it represented a new record for Bordeaux vineyard land. Shortly after selling to Patrice Pichet, the vineyard of Les Carmes Haut Brion was expanded by the purchase of another fifteen acres of vines.

Pichet has continued adding to their holdings of Les Carmes; in 2012, the group made another 40-acre purchase of vines from the Briest family, the owners of Château Haut Nouchet. Patrice Pichet has said they plan to completely replant the vineyard at a much higher vine density of 10,000 vines per hectare. Initially, the young vines will be used in the production of the second wine of Les Carmes Haut Brion, Le Clos de Carmes Haut Brion, and in time, it is expected the better vines will be added to increase the quantity of the Grand Vin.

Le Clos des Carmes Haut Brion (le C, as it is called) is made from the majority of the vineyard, so it is a much larger production. The vineyard is planted to 62% Cabernet Sauvignon, 35% Merlot, and 3% Petit Verdot, emphasizing Cabernet Sauvignon more than most other second wines.

Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($235) Pre-arrival

Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($235) Pre-arrival

Full-bodied, seamless and layered, this 2020 Grand Vin is intensely flavored but weightless, with a compelling sense of harmony and a long, orange-inflected finish. A blend of 40% Cabernet Franc, 34% Cabernet Sauvignon and 26% Merlot, it was vinified with 65% whole bunch. 2020 is considered the first modern vintage from this estate in which all the elements are so well balanced. Dark red/purplish fruit, rose petal, mint, lavender, dried herbs and incense.

Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion, 2018 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($265) Pre-arrival

Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion, 2018 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($265) Pre-arrival

In 2018, The growing season began with a benign winter, which quickly shifted to a turbulent and relentlessly wet spring. The weather oscillated between heavy rains and violent bouts of hail, which brought a myriad of problems, ranging from rot and diseases. In particular, the problems created by mildew were extensive and exhausting to deal with especially for producers whose organic certifications prevented them from using sprays or other such preventative measures. Fortunately, however, a hot arid summer came into play, which helped dry out the vines and free them of disease. Overall, the 2018 vintage for Pessac-Léognan was very good and some exceptional wines were made.

37% Cabernet Franc, 34% Cabernet Sauvignon, and 29% Merlot; this is, according to Jeb Dunnuck, a 100 point wine, juicy with cassis, cherry preserves and raspberry.

Second Wine Rethought: Le C des Carmes Haut-Brion

Considered less a ‘second wine’ and more ‘another featured wine’, Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion, Le C (short for ‘Les Clos’) relies on a more traditional blend that focuses on Cabernet Sauvignon subtly complemented by Merlot. It is made in a separate winery about a half an hour from where in the Grand Vin is made in Pessac.

“The fruit is in the spotlight, and consumed young, the wine develops a crisp intensity which will gain the patina of beautiful complexity as the years pass,” says Alice Leuret, Commercial director at Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion.

The estate has 12 acres under vine, with an overall grape variety distribution of 50% Merlot, 40% Cabernet Franc and 10% Cabernet Sauvignon. Much of the vines used were previously part of Châteaux Le Thill and Haut Nouchet.

The annual production of the red Grand Vin of Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion is approximately 4,000 cases.

Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion ‘Le C des Carmes Haut-Brion’, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($48) Pre-arrival

Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion ‘Le C des Carmes Haut-Brion’, 2020 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($48) Pre-arrival

60% Cabernet Sauvignon, 39% Merlot, 1% Petit Verdot (with an average age of 15 years) ; a remarkably assertive percentage of Cab Sauv creates a wine that shows an oceanic edge with nuances of sea salt minerality beneath notes of flowers, tobacco leaves, thyme, red and black currant, mint, and an array of spices, finishing with cocoa and espresso.

Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion ‘Le C des Carmes Haut-Brion’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($48) Pre-arrival

Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion ‘Le C des Carmes Haut-Brion’, 2019 Pessac-Léognan Rouge ($48) Pre-arrival

Again, a focus on Cab Sauv makes for a wine filled with smoky, dark red and black fruits, licorice, herbs, wet earth, cigar box, forest leaf, and salty, crushed rocks on the finish.

- - -

Posted on 2023.10.26 in Pessac-Léognan, Graves, France, Bordeaux | Read more...

Red Burgundy’s Strongest Statement Of ‘Blood And Iron’ Is Manifest in 2018 Gevrey-Chambertin Crafted By Two Newly-Reinvigorated Domaines

“The Emperor would drink only Chambertin.” – Louis Constant Wairy, Napoleon’s valet.

What does Gevrey-Chambertin have in common with Westland, Michigan? Not much, except that Westland was named for a mall and Gevrey-Chambertin was named for a vineyard. As those schooled in Burgundian lore know, during the nineteenth century it became fashionable for villages in the Côte d’Or to adopt double-barreled names, adding a hyphen followed by the name of their most famous vineyard: Thus Chambolle added Musigny and Gevrey added Chambertin.

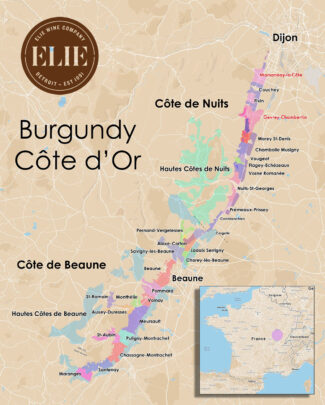

In minimalism, less may be more, and in wine—especially those with a hyphenated name—more may be less; a village-level Gevrey-Chambertin, for example, does not seek to compete with the quality of ‘Le Chambertin’ itself. But if nothing else, its name reminds you that it comes from a rarefied zip code. And to be sure, the region is hallowed grapeland, graced with the Holy Trinity of terroir—elevation, climate and soil structure. Contained within the appellation are nine Grand Crus and 26 Premier Crus (whose name on the label may be followed by the name of the climat of origin) as well as nearly a thousand acres of Village wine.

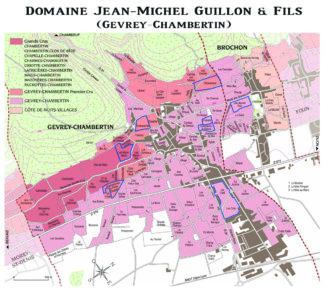

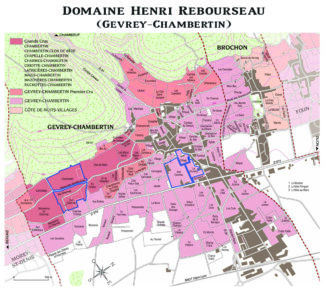

This week’s selection includes a cross-section of the various quality levels produced in Gevrey-Chambertin from two top producers, Domaine Henri Rebourseau and Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils. Also from Guillon are two wines from nearby Marsannay, an appellation so close to Gevrey-Chambertin that it might be referred to as Burgundy’s Queen to Gevrey’s King. But in truth, so splendid are these wines that they transcend arcane assignations of gender, coming, as they do, from truly nonbinary Elysian Fields.

The Essential Qualities of Gevrey-Chambertin

In the far northeast of Burgundy, about ten miles south of Dijon with the valley of Saône valley to the east, lies the Rodeo Drive of red wine, Gevrey-Chambertin. The town itself is touristy, picturesquely festooned with vineyards from end to end, but certainly one of the must-visit areas on any French wine tour. Should the tour include a tasting (and if it doesn’t, skip it), you’ll find that the wine, at all levels of quality, share certain characteristics, many of them in seeming contradiction: In general, Gevrey wines are big without being heavy, rich without being cloying and full-bodied while retaining a velvety, delicate texture.

This inherent tension is what makes Gevrey-Chambertin a superlative, even in the star-studded Côte de Nuits. But it must be remembered that this quality represents many centuries of trial and error: The best vineyards are based around the foothills of the famous hill of Lavaux, on the east-facing slope where they are hit by the morning sun, which disperses any fog and warms the vineyard into the late afternoon. Soils, of course, impart their geological magic–the vines in the Premier and Grand Cru sites are grown on shallow brown limestone with sections of clay which holds onto the heat of the day, warming the vines overnight and further increasing their ripeness and power. Organoleptically, the Pinot Noirs of Gevrey suggest blackcurrants and jammy strawberry compote when young, with distinct notes of licorice heightened by maturation in new oak casks. As these wines age, they acquire earthy notes aromas that hint at animal pelts, musk, spicy vanilla and Havana cigars. The top flight Crus are unparalleled, of course, and no more apt descriptor for them exists than ‘blood and iron.’

2018 Vintage: Powerful, Powerful, Voluptuous With Immediate Appeal

Calescent and copious—big words to describe a big vintage, equally fascinating and enjoyable for those who like potent, youthful Pinots and for those willing to wait out a prolonged span of aging.

A hot, dry summer generally requires a wet preceding winter to top up groundwater reserves, and 2017/18 was just that. Conditions warmed up in time for a beautiful early flowering—another requirement for a bountiful harvest. The summer, as indicated, was hot and dry, although the farther north you went, sporadic rainfall was welcomed. The only anomaly during the season was hail in Nuits Saint Georges; two storms striking the south of the village and Prémeaux-Prissey at the end of June and the beginning of July, wiping out as much as 40% of the crop in some vineyards.

Due to the heat, the picking window for Pinot Noir was short, as levels for sugars, acids and phenolics rose quickly and called for an early harvest. In addition, three success factors came into play: Winemaking style, a vineyard’s specific terroir and the age of the vines proved even more consequential variables than usual. Broadly speaking the wines are relatively low in acidity and relatively high in alcohol, rising from a modest 13% up to 14.5%.

The wines of Gevrey-Chambertin in particular offer a genuine sense of freshness hand-in-hand with the vintage’s characteristic and powerful sun-ripened fruit.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils

‘Local boy makes good’ is a common enough tale in Burgundy, where land—which can command a price tag twice that of Bordeaux—is generally held by families. Most success stories involve inheriting it or marrying it. Rare is the breakthrough of an outsider who can, for example, step off a train in Gevrey-Chambertin without connections or formal wine training and forge a Burgundian empire within an enclave already pretty imperialistic.

Enter Jean-Michel Guillon. Born into a military tradition, Jean-Michel Guillon chose to settle in France after his past service in the Polynesian Islands and in 1980, without much formal training, planted grapes on five acres of land. What began as a nascent fascination grew into an overarching passion, and the estate today covers nearly forty acres spread over more than 20 appellations. It is work that, like the best Gevrey-Chambertin wines, took years to peak, both stylistically and critically: 2020 turned out to be Jean-Michel Guillon’s best vintage ever.

He explains: “It is all the result of my love for this land, and any acclaim I have received is based on innovative production processes and more importantly, taking into account the ecological needs of the vine. The climate crisis and the scarcity of natural materials is taken very seriously at the winery. Global warming is at the heart of the destruction of habitat and the appearance of certain diseases. In order to facilitate cultivation and harvesting, we have worked diligently to reduce our carbon footprint by using phytosanitary products that respect the environment.”

Among his most aggressive innovations may be his use of new oak—100% at all levels, including the Bourgogne Rouge, his entry-level wine. On this front he quotes Henri Jayer, perhaps Burgundy’s most inventive winemaker: “There are no great wines without new barrels”. As such, Guillon & Fils is the biggest buyer of new French oak in Burgundy after Domaine de la Romanée-Conti and the Hospices de Beaune, most arranged through a long-standing partnership with the Ermitage and Cavin cooperages.

Jean-Michel and Alexis Guillon

And speaking of ‘fils’, after forty years of love and labor, the elegant Jean-Michel Guillon has adopted a Burgundian style of primogeniture after all, handing over the management of the estate to his son Alexis. Two younger sons are waiting in the wings, much like King Charles III; thus, in a roundabout way, Gevrey-Chambertin again earns the nickname ‘The King of Burgundy and the Burgundy of Kings.’

President of the wine association for 12 years and of the cellar of the Vignerons de Gevrey-Chambertin ‘La Halle Chambertin’, the elder Guillon’s winemaking career ended with participation in the Saint-Vincent Tournante 2020 in Gevrey-Chambertin.

The ‘Régionale’ Wine

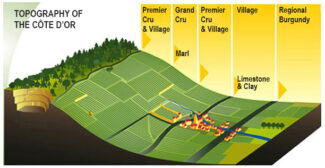

So specific are the ‘cru’ vineyards of Burgundy that ‘régionale’ vineyards may exist in the literal shadow of more renowned domains, occasionally separated by hundreds—or even as little as dozens of feet. Régionale wines tend to be somewhat generic, culled from vineyards located along the foot of more prestigious wine-growing slopes on limestone soil mixed with some clays and marls, where the earth is stony and quick-draining.

Unlike Bordeaux, where classifications are based on individual châteaux (capable of buying other vineyards and expanding), Burgundian label classifications are more geographically focused. A single vineyard, therefore, may have multiple owners, each with a small piece of the action. The non-specific ‘Bourgogne’ label first appeared in 1937, and in 2017, a further classification permitted wines from vineyards located within the Côte d’Or to be labeled as ‘Bourgogne Côte d’Or’; it’s a great tool for a consumer looking to explore the wide diversity of vineyard among the Hills of Gold while maintaining a terroir-focused, climat approach to Burgundy.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, ‘Terroir de Gevrey’ Bourgogne Rouge ($42)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, ‘Terroir de Gevrey’ Bourgogne Rouge ($42)

Ruby-red and luscious, this mineral-driven wine shows a pure, ripe and elegant nose of cassis and lightly spiced plum that complements the balanced body. The wood for which Guillon is famous is prominent but not dominant, allowing the berry notes to ooze through.

The ‘Village’ Wine

In the Burgundian hierarchy of classifications, wines allowed to label themselves ‘Villages’ make up about 37% of the wider appellation’s total production. Ranked above ‘Régionale’, it is the first category in which the concept of ‘terroir’ can truly be tested. Certain characteristics and styles are ascribed to wines from various villages and their surrounds. In fact, Burgundy is a constellation of villages, but only a handful produce wine good enough to warrant the label. With the same grape restrictions as Grand and Premier Crus (including a little Aligoté), Village wines have a slightly higher allowed yield per hectare.

When you’re number two, you try harder: At the Villages level, Gevrey-Chambertin is ranked second, below Vosne-Romanée and above Chambolle-Musigny.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, ‘Cuvée Alexis’ Gevrey-Chambertin ($98)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, ‘Cuvée Alexis’ Gevrey-Chambertin ($98)

Named after the (then) heir apparent Alexis (long live the new king), this blend is more elegant and perfumed than Guillon’s other Gevrey Villages wines, hailing from 60-year-old vines. It features an expressive nose peppered with pretty nuances of blackberries, wild herbs and smoky forest floor, yet the palate is fresh and fruity, displaying a full array of strawberry, cherry and sweet spice behind notes of iron filings and crushed stone.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, ‘Cuvée Père Galland’ Gevrey-Chambertin ($98)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, ‘Cuvée Père Galland’ Gevrey-Chambertin ($98)

Named for René Galland, the man who first helped Jean-Michel learn to make wine. As proper homage, the bouquet is almost fierce, rich and redolent of muscular dark fruit and iron, making it a remarkable Villages wine that could easily be mistaken for a Cru. It expands on the palate to include smoke, coffee, cola perfumed by fresh violets and lavender.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, ‘Vieilles Vignes’ Gevrey-Chambertin ($130)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, ‘Vieilles Vignes’ Gevrey-Chambertin ($130)

This hedonistic wine from 90-year-old vines is, as expected, perfumed on the nose and massive in the mouth, showing fresh figs, raspberries, black currants and orange zest on the palate and dry extract on a balanced and notably more complex finale.

The ‘Lieu-dit’ Wine

In the legal lexicon of French wine, a ‘lieu-dit’ is the smallest parcel that can be named in an appellation; it may be a vineyard, or part of a vineyard, or even a few rows of vines. It earns a name through consistently providing superior wine grapes. The term is often used interchangeably (and incorrectly) with ‘climat.’ In fact, one can find several lieux-dits within a single climat, or a climat that only covers part of a lieu-dit. In simple terms, ‘climat’ refers specifically to a winegrowing plot whereas ‘lieu-dit’ is a generic geographical term.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Gevrey-Chambertin ‘Les Crais’ ($78)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Gevrey-Chambertin ‘Les Crais’ ($78)

The Pinot Noir parcel ‘Les Crais’ sits east of the main road on the Brochon side of Gevrey-Chambertin; it was planted in two parts, one in 1979/1980 and the other in 1990/1991. Soils are gravel made of decomposed limestone. The wine is racy and intense with juicy raspberry aromas, ripe cherry and anise sparks, offering remarkable length.

The ‘Premier Cru’ Wines

A novice may point out that the illogic in the Cru hierarchy can be confusing, because Premier Cru is below Grand Cru, even though the word ‘premier’ translates literally as ‘first.’ A pro will quickly point out that logic is not always the best device to use when translating wine laws. Often abbreviated ‘1er Cru’, these wines—like all wines earning any sort of ‘Cru’ designation— represent excellent vineyards and make up about 10% of Burgundy’s wine production. A notch below Grand Cru, usually in price and arguably in quality, the size and gravitas of that notch is often a matter of taste. As a loose rule, Premier Cru vineyards are found just above or below these prime locations that have been granted Grand Cru status, while Village wine usually remain concentrated in the valleys. There are 635 vineyards designated Premier Cru in Burgundy.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru Les Champeaux ($144)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru Les Champeaux ($144)

Les Champeaux is a 17-acre vineyard at the northernmost limit of Gevrey-Chambertin, just south of Évocelles. Although Les Goulots and Combe aux Moines are above it, Les Champeaux is perched quite high on the slope, at one thousand to about 1400 feet elevation, facing east to southeast. Champeaux is a patchwork of smaller parcels, some of which are terraced, so the vineyard’s slope varies from gentle to steep. Guillon has produced wine from 40-year-old vines and displays a sensationally concentrated, intense palate behind a bouquet of black fruits and toasty new oak, giving a hint of licorice and spice to the finish.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru Les Champonnets ($153)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru Les Champonnets ($153)

Les Champonnets is situated on the same line as the Grand Crus, very near to Ruchottes-Chambertin, although it is tucked up high near the entrance of the Lavaux Valley. It contains a combination of old vines (60-70 years) interspersed with younger vines that are about half that age. The soil of Champonnets is deep, yet with a strong limestone component that shows through in the wine—deep and rich, with plush forest berries, undergrowth, humus, dusty chocolate and pie spice on the finish.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru La Petite Chapelle ($179)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru La Petite Chapelle ($179)

La Petite Chapelle is a ten-acre vineyard situated at the base of the Côte d’Or escarpment, one of the lowest-lying of the Premiers Crus and one of the easternmost in Gevrey-Chambertin, lying below the Chapelle-Chambertin Grand Cru climat, and just south of Cherbaudes. The enclave of En Ergot sits on Petite Chapelle’s southeastern quadrant. Guillon’s La Petit Chapelle displays itself in strong, crimson-garnet hues with discreet purple reflections. The nose is sweet cherry fruit, subtle raspberry and some hibiscus, opening to provide lime zest. It is juicy on the palate, taut, and juice with red berries and well-integrated tannins, salty minerality and nougat. It remains very youthful, with nice length and fine ageing potential.

The ‘Grand Cru’ Wine

Although Grand Cru production only makes up about 2% of all production, and although there are only 33 vineyards so named, it is likely that an even passing fan of Burgundy has heard of them all. This is truly where the crème de la crème of Pinot Noir exists and, in fact, they used to be called ‘Tête de Cuvée.’ Of course, there are several consecrated Grand Crus designated exclusively to Chardonnay, but none in Gevrey-Chambertin, which is red wine country. Grand Cru wines are generally allocated only to the well-connected and Michelin-starred cellars. Add to that the ever-expanding global competition for Burgundy and successive years of small harvests, and these legendary wines become even more difficult to find.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Mazis-Chambertin Grand Cru ($349)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Mazis-Chambertin Grand Cru ($349)

Mazis-Chambertin is the northernmost Grand Cru vineyard in the Côte de Nuits; it covers 22 acres of superb soil on the upper slopes of Gevrey-Chambertin’s Grand Cru belt. The vineyard is divided into two climats, the upper Les Mazis-Hauts and the lower Les Mazis-Bas, the latter having slightly deeper soils. Location, location, location: Mazis-Chambertin is on the same part of the slope as the Chambertin vineyard, about 1600 paces to the south, just beyond the similarly well-regarded Clos de Bèze. The Grand Cru Ruchottes climat lie on the slope above, to the west. As to the wine, a densely fruited nose of dark berries is at once earthy, spicy and feral. The imposingly-scaled, lavishly rich and sleekly muscled flavors are firmly structured though not aggressive and the sheer depth of the palate lingers throughout a long, fanning finish; impressive now, but clearly built to age.

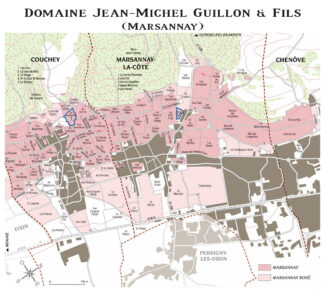

Marsannay: The Gateway to Gevrey-Chambertin

Referred to as the ‘The Côte de Nuits’ Golden Gate’, Marsannay produces wine in all three chromatic styles—red, white and rosé—but the reds, in particular, are heralded for their richness, resembling in style the wines of neighbors Fixin and Gevrey-Chambertin. As an appellation, Marsannay encompasses the communes of Chenôve, Marsannay-la-Côte and Couchey.

The best vines are planted mid-slope with easterly or southerly exposures, and have historically been considered of only modest quality, with no Premier Cru—and certainly no Grand Cru—sites. However this issue has been under review in recent years, and two neighboring sites, Clos du Roy and Les Longeroies, gained Marsannay Premier Cru status in 2020.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Marsannay ‘Clos des Portes’ Monopole ($63)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Marsannay ‘Clos des Portes’ Monopole ($63)

Although this is technically a Marsannay, the wine is made using the same standards Guillon applies to Chambertin—similar low yields drawn from seriously old vines and matured in 100% new barrels from Nivernais oak (made by master coopers at Tonnellerie Berthomieu). ‘Clos des Portes’ is monopole, meaning that Guillon owns the entire cru. The wine offers a ripe and distinctly earthy nose with aromas ranging from rich black to bright red fruits, leading to a seductively textured, medium-bodied mouthfeel that is juicy with mid-palate concentration.

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Marsannay ‘Les Quenicières’ ($61)

Domaine Jean-Michel Guillon & Fils, Marsannay ‘Les Quenicières’ ($61)

Lavishly oaked with creamy and toasty aromas behind the floral—peony, iris and clove. The mouth is round and gourmet. This wine reveals blackcurrant and spicy aromas with elegant tannins on the finish and persistent minerality also expressing earthy notes of fern, moss and truffle.