The Champagne Society October 2023 Selection: Champagne Hubert Noiret

The Evidence Of Things Terroir

Champagne Hubert Noiret’s Coteaux du Petit-Morin Single Vineyards

In Pursuit Of Authentic Expression Of Place Of Origin

The Coteaux du Petit-Morin – Village Villevenard

Champagne Hubert Noiret, Harvest 2019 Coteaux du Petit-Morin – Villevenard Lieu-dit ‘Pièce des Aulnes’ Extra-Brut (TCS Members $51, Regular $64) – 100% Meunier

Champagne Hubert Noiret ‘Cuvée des 3 Symboles’, 2013 Coteaux du Petit-Morin – Villevenard Lieu-dit ‘Les Bacons’ Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut – 100% Chardonnay (TCS Members $59, Regular $74)

Dear Member,

The soul of Champagne has always been finesse, and a Cellar Master’s decision to balance blends (in a search for complementary aromas and personalities) or to bottle a single variety is intended to be a statement. Listening to the winemaker’s voice in different incarnations of the same art form is to enjoy an ever-changing dialogue between man and grape.

It’s our normal practice to send out a single bottle as a bimonthly presentation, but this month, it will be two—one Blanc de Blancs and one Blanc de Noirs—from Champagne Hubert Noiret. Taste them individually or side-by-side; each is a unique reflection of Jean-Michel and Nathalie Noiret’s commitment to terroir expression through organic cultivation.

Listen to the conversation with your nose and palate and decide which one resonates best with your personality. Society members receive a thank-you special of 20% discount of the regular prices, so make sure your Thanksgiving Day get-together is well fueled with ice-breakers.

Elie

Wine is not about bubblegum halter tops or chunky flip-flops, but as an industry, it is as susceptible to fashion trends as any other. At Elie’s, we roll our eyes at some and embrace others with open arms and eager palates. Since the mid-1990s, as a whole, French winemakers (many fresh out of enology school) have made a concerted effort to employ organic methods in their vineyards, both as homage to the soil that produces grapes and as a planet-saving necessity.

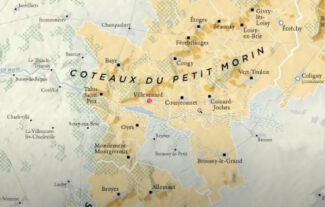

In Champagne, global warming has shifted the hierarchy of terroirs, allowing regions once considered marginal to seize a little limelight. Discovering these tiny pockets (Villevenard in the Coteaux du Petit-Morin, for example, has around three hundred acres under vine) as they begin to rise in the public’s estimation is one of the joys of being a merchant; getting to know the winemakers themselves is one of the privileges of being a wine lover.

A New Generation

If we are on the brink of another Golden Age of Champagne, the 70’s and ‘80’s might be viewed as the Dark Ages. The advent of industrialized farming and its overwrought dependence on synthetic fertilizers, pesticides and fungal treatment, stripped away a portion of the character that many wineries had spent centuries nurturing. The organic farming and an adherence to biodynamic principles that feature prominently in the practices of countless modern operations had its beginnings in the ‘back to the future’ outlook of this generation of winemakers, who took a rearview mirror to the methods of their forefathers and saw the folly of treating wine as a process rather than a reflection of place.

Champagne Hubert Noiret is this week’s ‘Exhibit A.’

Searching for Authenticity: Champagne as a Wine Like Any Other

Over the years we have emphasized that Champagne—however vaunted it is as a symbol, a ritual and an icon—is first and foremost, a wine. At a wedding, an anniversary or at two minutes passed midnight on New Year’s Day, you may lose track of this simple fact, but the men and women who work the cellars of Champagne do not. At its best, whether blended or not, Champagne expresses the site(s) upon which it is grown, and this is a wine fundamental that does not change because process adds carbonation. And it’s a fact that long before that carbonation is added, the still wine (vin clair), is evaluated at face value and many major houses isolate individual vineyards with specific characteristics at this point, the better to create a more complex and predictable final product.

Still Champagne, a subject about which we wrote recently, is an entirely different category, and was born in part from a warming climate which allows traditional cool weather Chardonnay and Pinot Noir (which serves sparkling Champagne best when slightly under-ripe and still electric with acidity) to ripen more completely on the vine. Such grapes make infinitely better non-carbonated wine, and are, in fact, the talk of the town in both Épernay and Reims.

Digging Deeper: Vineyard Specific Champagne

For a wine region that is a day-trip away from Burgundy, Champagne has showed a historical reluctance to focus on lieux-dits—vineyard-specific wines. In fact, Champagnes named for a particular village has been a rarity; Eugène Salon did it in 1905, and however legendary his Côte de Blancs has become, it was decades before anybody else did it, at least for public consumption.

But things are changing in Champagne—climate and zeitgeist, and the torch is being passed to a younger generation. In the 1990s, interest in experimentation took hold, and part of that innovative spirit involved the recognition that sites have personality—something that Champagne houses have long been obsessed with displaying. Blends can achieve a generic identity recognizable from vintage to vintage, and it is unlikely that single-cru models will replace this hegemonic tradition. But a new crop of chef de cave in Champagne are also increasingly aware that consumers have become interested in a more focused reading of terroir and that by attempting to express their vineyards with individuality rather than synergy when blended with others, an entirely new breed of wine-lovers will be engaged—those who recognize that any wine’s primary identity is drawn from the vine, not the label.

Detailing Coteaux du Petit-Morin

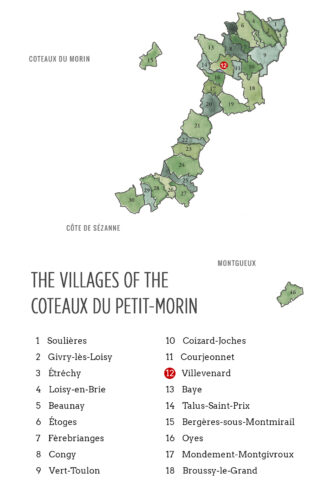

It’s all quiet on the western front—primarily because the Champagne-producing villages of Petit-Morin are located exclusively on the eastern front. This has traditionally been négociant country, where growers sell their grapes rather than produce wine. Although Coteaux du Petit-Morin is only fifteen miles from Épernay, it remains rural and true to its roots, where the vineyards are surrounded by open field and forested hillsides.

The region is frequently lumped in with the Côte de Sézanne or labeled ‘Val de Petit-Morin’ named after the river that has its source in the Val-des-Marais commune, part of the Côte des Blancs. But Olivier Collin of Ulysse Collin (the area’s largest producer) prefers to call his home-base ‘Coteaux du Petit-Morin’ after the hillsides on which the vines grow; he defines the territory in specific terms: “Côte de Sézanne begins at the villages of Broyes and Allemant, south of Villevenard. We run from Soulières in the north to Villevenard in the south, up to Vert-Toulon in the east. As you can see, we are quite unique from either Sézanne or Côte des Blancs”

He adds: “Pinot Meunier is more common than Chardonnay in the Val du Petit-Morin taken as a whole, while Chardonnay completely dominates the Côte des Blancs. The finest terroirs in Petit-Morin are peppered with black silex—a type of flint—that offers our Champagnes a smoky tone of minerality that is unique.”

Cyril Jeaunaux of Jeaunaux-Robin reinforces this statement: “We are often grouped with Côte des Blancs, but our aspect and terroir are completely different. Our soils contain much more clay and considerably less chalk; we have black silex and, whereas Côte des Blancs is nearly all Chardonnay, we excel at Meunier,” adding, “For me, it is a fairly recent phenomenon to be talking about individual plots and vineyard-specific Champagnes—maybe only for the last ten years. This is the same length of time since we began referring to Petit-Morin as a unique and self-contained regional appellation. As for terroir, my parents worked under the blending philosophy of the big Champagne houses, meaning that our wines were a balanced mix from many villages and multiple vineyards. For me, the ‘terroir revolution’—sometimes called the ‘Burgundian turnover’—has happened in my own time.”

Silex is a word that arises in nearly every conversation about Coteaux du Petit-Morin’s distinctive soil, and Aurélien Clément of Clément & Fils mentions that his own local silex deposits near Congy—mostly grey rather than black—were used for centuries and centuries before vineyards were planted. “Perhaps as long as seven thousand years ago, early man used it in tool-making,” he says.

Like Cyril Jeaunaux’s family, Clément adds, “My uncle and great-grandfather were more concerned with blends rather than the expression of ‘one blood’—meaning a single vineyard or commune. When our regional identity was legalized for use on our labels, we began to take a more focused look at the specific ground beneath our feet, seeing it, perhaps, as a chance of a new way of expressing our Champagnes.”

Marie Laurène Lefébure (Champagne Lefébure) is also a fan of Petit-Morin for the complexity of the soils, which she favors over the homogenous aspect of the Côte du Blanc; she mentions specifically the clays near her winery in Baye in the western part of the appellation and in particular, the ferrous content of her terroirs: “For me, this is more important than silex. Iron imparts a rich and sensual aroma that almost reminds one of blood. We love Meunier, of course, but our orientation allows us plots of Chardonnay, which here shows an exotic side—it is very unique, very baroque Chardonnay.”

Along with her husband Sébastien, Lefébure generally avoids the ‘fast-motion zeitgeist’ in modern Champagne, but is equally a proponent of natural approach to winemaking. In fact, the couple was assisted by the organic champagne pioneering family, the Horiots in building her small, low production winery.

Champagne Hubert Noiret

In Pursuit Of Authentic Expression Of Place Of Origin

The transition from wine growing to wine marketing, from selling your grapes to producers to becoming the producer yourself, often takes many generations. Such was the case with Hubert Noiret, a Champagne house in Villevenard commune of Petit-Morin formed in 2003 by Nathalie and Jean-Michel Noiret, whose families have been tending vineyards since the 18th century. Indeed, it is a background that has served the couple well.

Jean-Michel Noiret

Nathalie Hubert-Noiret

Says Nathalie: “We find that the ancestral techniques of our grandparents who used natural materials have been forgotten and replaced by chemistry. Used on a large scale, it has unbalanced the human environment and plant diversity in the name of comfort. Our life journey has made us understand that chemistry has limited human and plant life and created a phenomenon of resistance, which is why since 2011, we gradually rebalance the natural forces of life on all our plots via biodynamics. We reuse materials of natural origin at very low doses: copper against mildew and sulfur against powdery mildew—both essential for the protection of the vineyard and the production of great Champagne.”

Jean-Michel adds, “From a very young age, we followed our parents closely, but to try to understand what nature wants to give us, I would need at least 3 lifetimes. Ours is a profession of patience, where every detail counts to achieve excellence. We are blessed to be in a region of Champagne rich in a Neolithic past with a very diverse and varied geology. We move from the peat of the Marais de St. Gond to chalk, from marls to white and green clays, from sandy loams to clay loams; a geological palette of incredible richness, lending a character and a style to our Champagnes.”

Champagne Hubert Noiret Vineyards in Villevenard, a village in Coteaux du Petit-Morin

The Flinty Soils of Villevenard

Flint is a word with plenty of literary oomph—references range from Shakespeare (“O Cassius, you are yoked with a lamb that carries anger as the flint bears fire…) to Dickens (“Scrooge was hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire…).

It’s also a word used in wine descriptors to signify a wine with a minerality that approaches smokiness.

Whether or not the mineral itself is responsible for all the ‘flint’ tasting notes is debatable, since flint is chemically inert and virtually insoluble, and thus, odorless and tasteless. But soils that contain measurable quantities of flint still produce iconic wines. This is true especially in Coteaux du Petit-Morin, where Silex Noir, a rare black flint, is found. It is a soil component most associated with a small corner of Vouvray, but which reappears in the terroir of Villevenard.

But for a vineyard? Besides making hard tools for prehistoric man, it’s a great marketing tool for modern wineries. It’s true that flint pebbles provide good drainage, and being inert, restrict nutrient availability, making for meager soils—the kind that tend to deliver finer grapes. At the same time, in overly dry areas, flint pebbles can promote the localized formation of dew, which leads to increased microbial activity and more organic matter beneath the stones. All this promotes a good soil structure. But does flint influence the taste of the wine itself? Alas, vine roots are demonstrably incapable of absorbing and using a solid, inert compound such as silica, which is tasteless anyway.

Wine is poetry in a glass, however, so we’ll raise one to the power of literary allusions.

2019 Vintage in Coteaux du Petit-Morin

The 2019 growing season began with an unusually mild preceding winter—February even brought relative warmth, and these conditions continued into the spring. The mild conditions allowed for the development of powdery mildew which affected some vines. Spring continued on a balmy trajectory until temperatures took a sudden drop in April and severe frosts dramatically cut yields in April. A wet May and early June continued to exacerbate the problem with downy mildew. It was only when temperatures finally heated up mid-June that rot and disease were controlled. A fierce summer set in, with July seeing a searing heatwave, but there was enough water retention in the soils that drought was never really a problem and nights were cool enough that acidity was, for the most part, retained. However, August saw brutal hailstorms ravage vineyards, particularly in the Côte des Blancs, severely cutting yields.

Although, the harvest promised to be small, with careful sorting needed, the overall quality was high. The grapes that survived the growing season in good condition tended to be particularly ripe from the summer sun while still retaining their aromatic character.

Champagne Hubert Noiret, Harvest 2019 Coteaux du Petit-Morin – Villevenard Lieu-dit ‘Pièce des Aulnes’ Extra-Brut ($64)

Champagne Hubert Noiret, Harvest 2019 Coteaux du Petit-Morin – Villevenard Lieu-dit ‘Pièce des Aulnes’ Extra-Brut ($64)

From a lieu-dit planted in 1962, this 100% Meunier originated as a special selection grafted onto a little-used rootstock. The south-facing vineyard is tended biodynamically (including herbal decoctions and specially prepared teas) using a maintenance method that the Noirets refer to as ‘equine weeding.’

The grapes are picked manually, then receive traditional pressing and are fermented and aged in 228- and 300-liter oak barrels. Dosed at 3 grams/liter, the wine shows aromas of orchard fruit, light herbs, brioche and pepper with ripe citrus and apple on the palate. The vin clair was bottled July 2020 and disgorged in July 2022. 1745 bottles made.

2013 Vintage in Coteaux du Petit-Morin

Both the winter and spring were cold and wet, delaying first budburst and then flowering. Young grapes suffered millerandage and coulure due to the cool temperatures, which cut yields. However, the reduced crops tended to ripen more easily during what transpired to be a long, cool growing season. Despite summer temperatures never really heating up, conditions remained fairly consistent, and a warm, sunny September provided just enough warmth to rescue the harvest. Many producers chose to pick later than usual to take advantage of the positive turn in the weather.

Champagne Hubert Noiret ‘Cuvée des 3 Symboles’, 2013 Coteaux du Petit-Morin – Villevenard Lieu-dit ‘Les Bacons’ Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut ($74)

Champagne Hubert Noiret ‘Cuvée des 3 Symboles’, 2013 Coteaux du Petit-Morin – Villevenard Lieu-dit ‘Les Bacons’ Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut ($74)

From the single-plot ‘Les Bacons’ planted between 1969 and 1984; the site is northeast of Villevenard with a gentle west-facing slope. The soils are clay-rich with some black flint above a subsoil of chalk. Cuvée 3 Symboles is 100% Chardonnay from this site and shows toasty notes above a caressing, creamy character.

The wine is manually harvested and traditionally pressed, then aged for 10 to 12 months in 300-liter oak barrels on fine lees. The vin clair was bottled July 2014, disgorged in April 2022 and dosed at 5 grams/liter. 1750 bottles made.

2014 Vintage in Coteaux du Petit-Morin

A warm, dry spring got the growing season off to a quick and healthy start; both budburst and flowering were successful, and the absence of any severe frost gave producers cause for optimism. However, all that crashed to a halt as the summer proved to be damp. July and August were cool and wet with only the latter half of August eventually drying out. Although the large volume of rain was enough to make rot a concern, cooling breezes kept it at bay. A benign September brought warm, dry conditions, ripening the grapes and effectively saving the harvest.

Champagne Hubert Noiret ‘Cuvée des 3 Symboles’, 2014 Coteaux du Petit-Morin – Villevenard Lieu-dit’ Les Bacons’ Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut ($74)

Champagne Hubert Noiret ‘Cuvée des 3 Symboles’, 2014 Coteaux du Petit-Morin – Villevenard Lieu-dit’ Les Bacons’ Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut ($74)

The wine is manually harvested and traditionally pressed, then aged for 10 to 12 months in 300 liter oak barrels on fine lees. 100% Chardonnay, bottled in July 2015, disgorged in April 2022 and dosed at 5 grams/liter. 1750 bottles produced.

Notebook ….

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

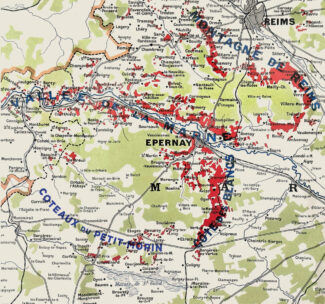

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

The lauded wine writer Peter Liem expands the number of sub-regions from four to seven, dividing the Vallée de la Marne into the Grand Vallée and the Vallée de la Marne; adding the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay and combining the disparate zones between the heart of Champagne and Côte de Bar into a single sub-zone.

Lying beyond even Liem’s overview is a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that compliment or contrast when final cuvées are created.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Épernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

Single Harvest vs. Vintage

In France, under Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) rules, vintage Champagnes must be aged for three years—more than twice the required aging time for NV Champagne. The additional years on the yeast is said to add complexity and texture to the finished wine, and the price commanded by Vintage Champagne may in part be accounted for by the cellar space the wine takes up while aging.

On the other hand, a Champagne maker might prefer to release wine from a single vintage without the aging requirement; the freshness inherent in non-vintage Champagnes is one of its effervescent highlights. In this case, the wine label may announce the year, but the Champagne itself is referred to as ‘Single Harvest’ rather than ‘Vintage’.

- - -

Posted on 2023.10.01 in France, The Champagne Society, Champagne

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Aglianico, Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Beaune, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Clairette, Corvina, Cot, Counoise, Erbamat, Ferrol, Fiano, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Fumin, Garnacha, Gewurztraminer, Godello, Graciano, Grenache, Grolleau, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Melon de Bourgogne, Merlot, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montepulciano, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscadelle, Muscat, Natural, Nero d'Avola, Parellada, Patrimonio, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Auxerrois, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Rondinella, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sangiovese, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Viognier, Viura, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- February 2004

Search