Champagne in Three Acts: Vincent Lagille’s Quest for Terroir Clarity Through Single Varietals – With Tension, Timing, and Thoughtful Restraint as His Guides

The quietest revolution Champagne has begun to increase its volume, and the emerging focus on parcel-based wines relying on single varietals to reflect terroir is moving closer to center stage. In a region where blends and house styles has been a hallowed hallmark to ensure homogenized quality, the shift to parcels and monovarietal wines is Champagne’s modern nod to authenticity.

The chief concession made by winemakers who are after this specificity of expression is volume: Parcels in Champagne are the norm (the result of hereditary fragmentation), and they are often quite small. Bottlings from individual plots results in limited production, making these wines rare and sought after. Of course, the exclusivity only adds to their allure.

Enter Vincent Lagille from Vallée de L’Ardre on the western slopes of Montagne de Reims, who has shifted his family’s focus on wine sold only to private customers to a broader, public outreach. Sworn to biodynamic principles, he has been exploring the potential of his family’s vineyards in Treslon, plot by plot, where Meunier is the dominant variety.

Here we feature his monovarietal and site-specific Champagnes as an ideal example of the region’s ‘newthink.’

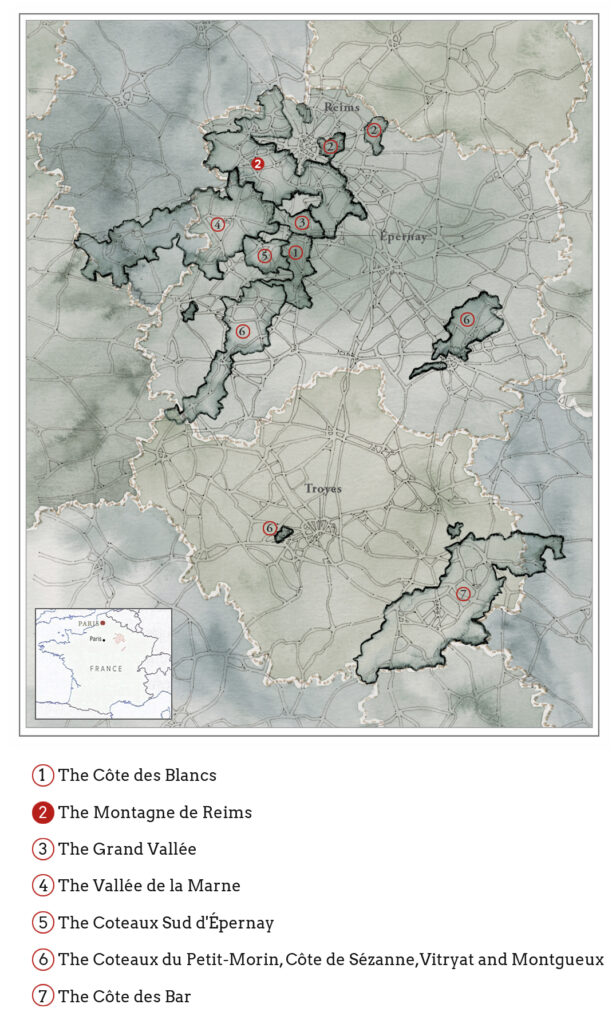

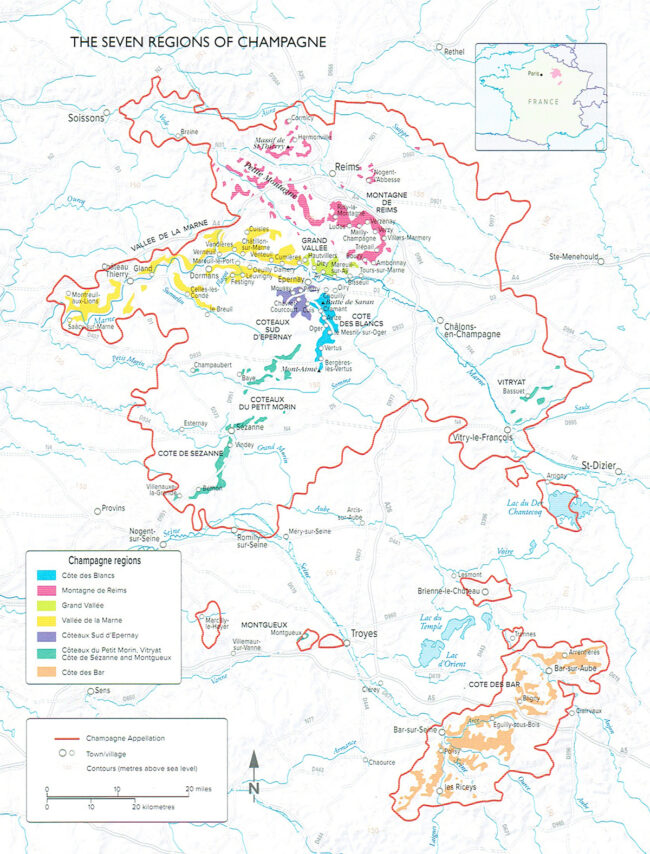

The Regions of Champagne

The Petite Montagne: On the Western Edge of Reims, Distinctive Terroir and a Patchwork of Soils and Styles

So varied are the soils, topographies and microclimates of the Montagne de Reims that it is not possible to speak of the region in any unified sense. Grande Montagne de Reims, which contains all of the region’s Grand Cru vineyards, covers the northern, eastern and southern slopes of the viticultural area, and Pinot Noir plantings dominate at 57%, followed by Chardonnay (30%) and Meunier (13%). Its vineyards face a multitude of directions, and soil type varies by village, giving rise to a breadth of Pinot Noir expressions, as well as exceptional Chardonnay.

To the west, the Grande Montagne de Reims gives way to the Petite, whose bedrock is chalk, but softer than the chalk found further south on the Côte des Blancs. This sort, called ‘tuffeau’, is an extremely porous, sand-rich, calcium carbonate rock similar to what is found in wine regions of the middle Loire Valley. In French, the word ‘petite’ often to refers to a ‘lesser’ commodity, but with La Petite Montagne, the reference is to elevation. This lower elevation means warmer weather, even in Champagne’s northerly climate, and in certain villages, the soils contain more sand, making it an ideal environment for growing Meunier.

Meunier accounts for approximately half of the plantings in the Petite Montagne, with Pinot Noir making up 35% and the rest Chardonnay. It is a growing conviction among growers of the modern era that Meunier is a Champagne grape whose time has come, especially as an age-worthy variety. Emmanuel Brochet of Villers-aux-Noeuds says, “People claim that Meunier ages too quickly, even faster than Chardonnay. I disagree. The curve of evolution is different. Meunier is quick to open and more approachable in youth, but then it becomes quite stable. Chardonnay tends to open later, but old Meunier remains very fresh and lively.”

The Villages of The Montagne de Reims

Vincent Lagille

Champagne Domaine Lagille

A Vigneron’s Pursuit of Verticality, Variety, and the Voice of the Vineyard

When asked if he and his sister Maud feel strongly about their roots in Treslon, where their family has been winegrowers since the 17th century, Vincent Lagille responds succinctly: “This is a form of obviousness.”

Maud Lagille adds, “I don’t even know if it would be possible to imagine us anywhere else.”

“We are the ambassadors of Treslon,” Vincent says, “and these wines reflect the terroir of the village. To achieve the truest expression, technique is everything, even when it means experimenting beyond the norm. Our Meunier is cultivated in Cordon de Royat, a system usually reserved for the Grand Cru vineyards of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Minimal dosage is our standard and aging is done in barrels that have already been used for up to ten vintages to minimize the influence of oak.”

Vincent Lagille, Champagne Domaine Lagille

Treslon nestles in the Vallée de l’Ardre, a stone’s toss from Reims. The Lagille domain covers 18 acres, planted to 55% Meunier, 30% Chardonnay, and 15% in Pinot Noir, and the focus of winemaker Vincent Lagille is on individual expression in a number of parcellaires—lieux-dits—of which he specializes in monovarietal wines. His only blend, in fact, is ‘Cuvée Grande Réserve.’

Pushing the envelope still further, Vincet has been fermenting certain harvests in glass globes and relying on baie par baie (hand-destemming) vinification, a time-consuming method that originated in Nuits-Saint-Georges. Many of these methods, unique to Montagne-de-Reims—were the result of trial and error:

“I fumbled for several years,” he admits, “With Maud and Claire (our second sister who worked with us from 2004 to 2021), we were constantly questioning ourselves. In 2017, I had a click. In connection with training on the issue of soils. It has become crystal clear. I wanted local wines. Wines that tell about our roots. Family roots, but also cultural roots. For this, I wanted the terroir to be able to express itself, for the vine to be able to draw deep into the soil. We have therefore undertaken to modify our cultivation practices. And today, we have made the choice to move towards organic certification.”

Rooted in The Petite Montagne: Treslon’s Singular Voice

The Lagilles may call themselves ‘The Ambassadors of Treslon,’ but in truth, they don’t have a lot of competition. The small community (located on top of the northwestern part of the Montagne de Reims hill where the small stream Ruisseau de Treslon empties into the Ardre river) has only 216 residents and nine grower/producers.

Treslon’s 600 or so vineyard acres are located north and northwest of the village in a band above the road between Faverolles-et-Coëmy and Treslon. They are predominantly south-facing slopes where Meunier is the dominant variety.

One Variety at a Time: Nothing Added, Nothing Lost

Hand-in-hand with single-vineyard Champagne goes single-variety cuvées, and despite the region’s historical reliance on blends, single-grape wines are a lens that can magnify site expression and vintage transparency. Without the layering effect of blending, the grape’s natural structure and tension take center stage.

“I think that’s really our thing,” says Vincent Lagille when asked about single-variety cuvées. “Only our Cuvée Grande Réserve is a blend. For the rest, the choice is clear to allow the expression of our terroir through each grape variety individually.”

To achieve this goal required a lot of research and observation on his part, and years of field work: “I followed the harvest circuit, when the collection of grapes takes place exactly when they are the most interesting. I learned to walk around my vines several times, so that I do not to miss the best moment. I’ like to collect the Meuniers at around 10.5 degrees [brix], while Pinots Noirs are just amazing at 11.5 degrees. For Chardonnays, it’s different. It varies more depending on years and plots.”

Les Bergères, La Garenne and Le Mont en Peine are the parcels that he finds most inspirational and he treats them differently than the rest of his range after harvest, especially through use of a technique known as fractionation. This involves altering the pressure at various times to fractionalize the quality and properties of the grape juice: First juice, for example, is released with minimal pressure and is considered the highest quality with delicate flavors, aromas and a good balance of sugar and acidity. As pressure increases, more juice is extracted, potentially containing more phenolics, including tannins.

From there, it is down to cellar technique, including minimal dosage, passage in barrels and the never-ending search for tension in the wines and plots. Vincent says, “I start with what I love. For example, regarding chaptalization, I always explain that I am a huge tea lover, and as such, I never put sugar in it. For me, that masks the essence of the product.”

And when it comes to wine, that mask is something that Vincent has dedicated his entire professional life to removing.

Shaped by Clay, Ready for Respect: The Reappraisal of Meunier

Most of the Meunier in Montagne-de-Reims (which accounts for about 34% of its vineyards) is planted to the west, towards Vallée de la Marne, though it remains an important blending component throughout the region.

Across Champagne in general, it’s a variety whose qualities are being reconsidered: Early to bud and early to ripen, it is a practical grape, but in the correct hands it produces nicely structured and age-worthy wines which remain approachable on release, The top producers are from Premier sites rather than Grand Crus.

Meunier thrives in the argilo-calcaire (clay/limestone) soils where Pinot Noir falters, especially on the cooler slopes of the Vallée de la Marne and the Petite Montagne. When fully ripe, Meunier produces wines that are fruitier and more ample when young, which is why it’s often blended in nonvintage Champagnes intended for early consumption.

Champagne Domaine Lagille ‘L’Inattendue’, Montagne-de-Reims ‘Village Treslon’ Blanc-de-Noirs Extra-Brut ($67)

Champagne Domaine Lagille ‘L’Inattendue’, Montagne-de-Reims ‘Village Treslon’ Blanc-de-Noirs Extra-Brut ($67)

The name means ‘unexpected,’ and that’s because the cuvée is a unicorn—a rare example of a single-varietal, entry-level Champagne made purely of the Meunier. The wine aged for three years before disgorgement and was given a low dosage of around 2 grams per liter. It displays vibrant fruit, elegant acidity and a savory finish.

Disgorged in December 2024.

Champagne Domaine Lagille ‘Fleur de Meunier’, Montagne-de-Reims ‘Village Treslon’ Rosé Extra-Brut ($73)

Champagne Domaine Lagille ‘Fleur de Meunier’, Montagne-de-Reims ‘Village Treslon’ Rosé Extra-Brut ($73)

100% Meunier, this rosé is crafted through cold maceration of hand-selected grapes, then fermented in both fût de chêne and stainless steel, following which it remains on its lees for five years. Dosage is limited to 3 grams per liter, balancing freshness and structure. The wine shows a nose of red currant and raspberry with a citrus undertone; the bead is extremely fine.

Disgorged in November 2024.

Champagne’s Chameleon: Pinot Noir in All Its Vigor, Deeply Site-Specific

Within Montagne de Reims, Pinot Noir is the most widely planted grape, some standing on its own but most a vital component in blends. Pinot Noir in Champagne is much different than Pinot Noir in Burgundy, being lighter-bodied, virtually tannin-free, producing floral, red-fruit notes often subsumed into long lees aging. On chalk-limestone soils—which is where Chardonnay is usually planted—Pinot Noir is delicate, elegant and vibrant; on clay soils, the wines become heavier. On the western edge of Montagne de Reims there are sandy soils, though these plots often contain Meunier. Many vineyards have a mixture of soils, so it’s important for the grower/producer to understand exactly where the fruit is being grown.

Champagne Domaine Lagille ‘Les Bergères’, 2020 Montagne-de-Reims ‘Village Treslon’ Blanc-de-Noirs Brut-Nature ($126)

Champagne Domaine Lagille ‘Les Bergères’, 2020 Montagne-de-Reims ‘Village Treslon’ Blanc-de-Noirs Brut-Nature ($126)

One of four brut natures in the domain’s parcellaire collection, ‘Les Bergères’ (The Shepherdesses) is a plot of 40-year-old-vine Pinot Noir that Vincent calls ‘Pinot of the Sun’ due to the plot’s southern exposure. “Les Bergères is 300 meters from our premises,” he says, “It has always been exceptional, rarely affected by diseases or parasites”

The wine shows sweet notes of plum tarts and ripe drupes with a refreshing and persistent roundness, and a fresh saline finish. Great structure, balanced minerality and a persistent, fruity finish.

Disgorged in November 2024. A total of 1,780 bottles were released. No dosage.

Chalk and Citrus: Chardonnay’s Minerality and the Promise of Time

Although Montagne de Reims is mostly associated with red grapes, 25% of production is Chardonnay. It’s planted in pockets across Montagne de Reims, in styles quite distinct from Côte des Blancs further to the south, and even produces a still, skin-contact wine under the Coteaux Champenois appellation. Chardonnay is an earlier budder than Pinot Noir, making spring frost an issue. It remains an indispensable blending grape, despite facing several challenges: It is thin-skinned, for example, making it susceptible to botrytis, which can be a problem with Champagne’s wet weather. In its most classical incarnation, Chardonnay creates a citrusy wine of high acidity marked by chalky minerality.

Champagne Domaine Lagille ‘Le Mont-en-Peine’ 2021 Montagne-de-Reims ‘Village Treslon’ Brut-Nature ($126)

Champagne Domaine Lagille ‘Le Mont-en-Peine’ 2021 Montagne-de-Reims ‘Village Treslon’ Brut-Nature ($126)

100% Chardonnay from the Le Mont-en-Peine vineyard—the illustration on the label depicts Vincent as a child lugging around a wine barrel. The bouquet shows lemon curd, green apple, grapefruit and salted caramel; the palate leans toward lime peel and brioche with energetic acidity and a crisp finish.

Disgorged in October 2024. Only 1,504 bottles were produced without dosage.

Notebook …

Champagne’s Vin de Lieu: A Shift Toward Site and Identity

For a wine region that is a day-trip away from Burgundy, Champagne has showed a historical reluctance to focus on lieux-dits—vineyard-specific wines. In fact, Champagnes named for a particular village has been a rarity; Eugène Salon did it in 1905, and however legendary his Côte des Blancs has become, it was decades before anybody else did it, at least for public consumption.

But things are changing in Champagne—climate and zeitgeist, and the torch is being passed to a younger generation. In the 1990s, interest in experimentation took hold, and part of that innovative spirit involved the recognition that sites have personality—something that Champagne houses have long been obsessed with displaying. Blends can achieve a generic identity recognizable from vintage to vintage, and it is unlikely that single-cru models will replace this hegemonic tradition. But a new crop of chefs de cave in Champagne are also increasingly aware that consumers have become interested in a more focused reading of terroir and that by attempting to express their vineyards with individuality rather than synergy when blended with others, an entirely new breed of wine-lovers will be engaged—those who recognize that any wine’s primary identity is drawn from the vine, not the label.

A Matter of Geography: Drawing the Lines, Defining the Regions of Champagne

To be Champagne is to be an aristocrat. Your origins may be humble and your feet may be in the dirt; your hands are scarred from pruning and your back aches from moving barrels. But your head is always in the stars.

As such, the struggle to preserve its identity has been at the heart of Champagne’s self-confidence. Although the Champagne controlled designation of origin (AOC) wasn’t recognized until 1936, defense of the designation by its producers goes back much further. Since the first bubble burst in the first glass of sparkling wine in Hautvillers Abbey, producers in Champagne have maintained that their terroirs are unique to the region and any other wine that bears the name is a pretender to their effervescent throne.

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.

The lauded wine writer Peter Liem expands the number of sub-regions from four to seven, dividing the Vallée de la Marne into the Grand Vallée and the Vallée de la Marne; adding the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay and combining the disparate zones between the heart of Champagne and Côte de Bar into a single sub-zone.

Lying beyond even Liem’s overview is a permutation of particulars; there are nearly as many micro-terroirs in Champagne as there are vineyard plots. Climate, subsoil and elevation are immutable; the talent, philosophies and techniques of the growers and producers are not. Ideally, every plot is worked according to its individual profile to establish a stamp of origin, creating unique wines that compliment or contrast when final cuvées are created.

Champagne is predominantly made up of relatively flat countryside where cereal grain is the agricultural mainstay. Gently undulating hills are higher and more pronounced in the north, near the Ardennes, and in the south, an area known as the Plateau de Langres, and the most renowned vineyards lie on the chalky hills to the southwest of Reims and around the town of Épernay. Moderately steep terrain creates ideal vineyard sites by combining the superb drainage characteristic of chalky soils with excellent sun exposure, especially on south and east facing slopes.

… Yet another reason why this tiny slice of northern France, a mere 132 square miles, remains both elite and precious.

RECENT ARRIVAL

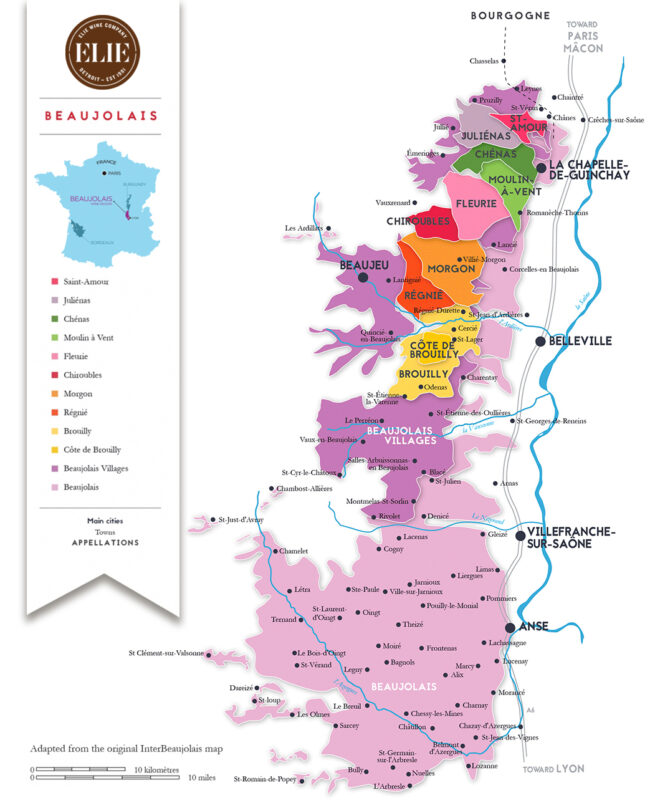

From Beaujolais’s Northern Frontier

The Cru That Doesn’t Conform

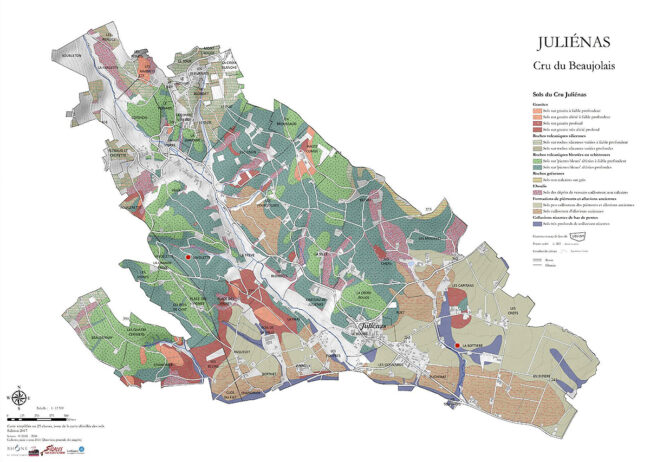

Juliénas, named for Julius Caesar, often gets the sort of dismissal as the Roman leader did on the Ides of March. Small, and with a somewhat noncohesive identity born of inconsistent terroirs, Juliénas soils are transitional, ranging from granite further up in the hills to the west to more sedimentary and alluvial soil in the east nearer the river. The ground contains a lot of clay, making irrigation unnecessary (and illegal), but resulting in wines that can be heavy and short-lived.

To succeed in Juliénas, a winemaker needs to be in perfect sync with the environment and consider stepping outside the box a bit in technique and foresight. Clément Beaupère is such a man. His rethinking of vine spacing and his willingness to shake up the ‘established’ approach in a hidebound Cru is making delicious purple waves.

Juliénas: The Structured Side of Beaujolais

Juliénas, at the northern end of the Crus, is also among the most elevated. Slopes are steep, but this verticality is ideal for sunshine basking, allowing grapes to ripen easily here, giving the wines more flesh and backbone. The terroir is as varied as any in a single Cru, with less granite and more ‘blue stone’—a friable, decomposed volcanic schist that the locals call ‘terre pourrie’, or ‘rotten rock.’ The many soils of Juliénas produce such an array of wines that there is no true Juliénas style, although they can be counted on to display a heart of stone and a soul of fresh forward fruit.

Vintage Report | Beaujolais 2023: Expressive, Balanced and Built to Last

As was the case throughout Beaujolais, Juliénas had a beautiful 2023 with many of the wines showing promise. The growing season kicked off with a mild winter and a somewhat haphazard spring where days ricocheted between unseasonably warm and unseasonably cool. There was no frost, however, and both budbreak and flowering were reasonably successful. The summer months were warm and very dry, although in the north, drought was less a concern. Harvest took place early September and wrapped up towards the end of the month; the grapes, for the most part, were perfectly ripe and nicely balanced.

Domaine David-Beaupère

Crafting Juliénas from the Ground Up, in Concrete

When an engineer takes over a vineyard, you wind up with a lot of math equations, and such is the case with Louis-Clément David Beaupère. After leaving his agricultural engineering studies at ISARA to take over the family’s ten acre domain, he says, “My goal is to reduce planting density significantly as to be able to trellis the vines and move away from the goblet vine training style of Gamay so ubiquitous in the region. Goblet vine training leads to overlapping positions on the vine and therefore uneven ripening of the fruit. As it stands, my yields average around 40-45 hectoliters per hectare which I intend to maintain while reducing the amount of vines per hectare.”

Got it?

In any case, Clément (as he prefers to be called) took over the estate in 2008. His grandfather, who raised his family in Algeria, had purchased the vineyard in 1962 after the Algerian War of Independence, but sold the grapes to the local co-op rather than bottle his own label. Clément’s father named the estate, but it did not reach its true potential until Clément began the long and arduous process of converting the vines to organic and shifting to natural processes in the cellar.

Domaine David-Beaupère

The winery is surrounded by La Bottìere, one of Juliénas’ most prized climats. Like Bottìere, Domaine David-Beaupère’s vineyard is planted on a mix blue diorite, richer soils and a lack of granite (in contrast to much of Beaujolais.) Beaupère vines are over 70 years old.

The other major Beaupère holding is the steep slope of Vayolette—atypical of Juliénas, with poor, stony soil and increases his holdings to just under thirty acres. “I love working with these two rather distinct vineyards,” Clément says. “It allows me to capture a fuller range of the expressions that Juliénas is capable of offering.”

A lot of that Juliénas expression is coaxed out in the cellar. In the cellar, Clément works naturally and in the tradition of many of the region’s greats: Long whole bunch macerations in concrete tanks followed by 8-9 months aging in a combination of very old barrels and tanks. The wines are never filtered, and a small amount of Sulfur Dioxide (SO2) is added, although he has begun to experiment with no-sulfur cuvées in recent years.

These wines are charming and can certainly be consumed young, but their underlying strength, structure and deep complexity means that they can benefit from a few years in the cellar.

Domaine David-Beaupère, 2023 Juliénas ($42)

Domaine David-Beaupère, 2023 Juliénas ($42)

Clément’s entry-level Juliénas is a beautiful example of the purity and terroir reflection that he brings to every bottle. Ripe with concentrated dark cherry, cassis and baking spices, the palate shows both tar and violets wrapped in bright acidity and smooth tannins.

Domaine David-Beaupère, 2023 Juliénas ‘Vayolette’ ($64)

Domaine David-Beaupère, 2023 Juliénas ‘Vayolette’ ($64)

From Clément’s nine-acre parcel in Vayolette climat where 45 year old Gamay vines are farmed organically, hand-harvested and allowed a 25-day maceration in concrete vats before pressing, and then ages in neutral barrels for nine months. Like the slope on which the vineyard is located, the wine is angular and structured, showing plum, raspberry and pomegranate behind brisk acidity and soft tannins. This is a wine capable of cellaring for several years.

Domaine David-Beaupère ‘Jules Chauvet’, 2023 Beaujolais-Villages ($37)

Domaine David-Beaupère ‘Jules Chauvet’, 2023 Beaujolais-Villages ($37)

Clément works two vineyards in La Chapelle-de-Guinchay; the smaller is an old parcel of Jules Chauvet’s, who was born here. Chauvet, often referred to as the Godfather of Natural Wine, advocated for low-intervention winemaking—techniques which Clément also employs. The wine is floral and expressive with red cherries and plums with appealing spice on the finish.

Domaine David-Beaupère ‘Let The People Faire La Teuf’ 2023 VdF Beaujolais ‘Gamay’ ($30)

Domaine David-Beaupère ‘Let The People Faire La Teuf’ 2023 VdF Beaujolais ‘Gamay’ ($30)

“Let the People Party” sounds like a battle cry from a rock band. Fermented and aged in concrete in order to highlight its fresh and vibrant character, this Vin de France (VdF) is no simple table wine, but rather an example of a pure and tart Gamay with notes of cranberry, rhubarb and a touch of clove.

Domaine David-Beaupère, 2023 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Chassignol’ 1.5 Liter ($120)

Domaine David-Beaupère, 2023 Moulin-à-Vent ‘Chassignol’ 1.5 Liter ($120)

Clément took over a steep Moulin-à-Vent vineyard called ‘Chassignol’ planted in the 1950s, some of which he has torn up to plant according to his preferred spacing, planting grass between rows to slow erosion. The wine is ripe and rich with nice structure with notes of red currant, licorice, tar, graphite and baking spice.

- - -

Posted on 2025.08.08 in Juliénas, France, Beaujolais, Champagne, Wine-Aid Packages

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Albarino, Albarín Tinto, Alicante Bouschet, Aligote, Altesse, Arbanne, Auxerrois, Barbarossa, barbera, Biancu Gentile, Bonarda, bourboulenc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Chenin Blanc, Cinsault, Clairette, Cortese, Corvinone, Cot, Counoise, Dolcetto, Erbamat, Fiano, folle Blanche, Fromenteau, Fumin, Gamay, Garganega, Garnacha Tintorera, Gewurztraminer, Godello, Graciano, Grenache Blanc, Groppello, Jacquère, Juan Garcia, Lladoner Pelut, Loureira, Macabeo, Maconnais, Malbec, manseng, Marcelan, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Melon de Bourgogne, Mencía, Merlot, Montanaccia, Montepulciano, Montònega, Moscatell, Mourv, Mourvèdre, Muscadelle, Muscat, Natural, Nebbiolo, Niellucciu, Palomino, Parellada, Patrimonio, Pecorino, Pedro Ximénez, Persan, Petit Meslier, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Auxerrois, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Pouilly Fuisse, Pouilly Loche, Riesling, Rousanne, Sagrantino, Sangiovese, Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc, Sciacarellu, Semillon, Serine, Sparkling, Sumoll, Tempranillo, Teroldego, Timorasso, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, trepat, Ugni Blanc, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Viognier, Viura, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Search