Qué Será, Syrah: How One Grape Speaks the Vernacular of Five Northern Rhône Appellations, Through Ten Producers.

The triumvirate of Côte-Rôtie, Cornas and Hermitage rule the narrow terraces of Northern Rhône indomitably and are responsible for the world’s best Syrahs. They’ve been called ‘unicorn wines’ in that the best of them are rare, and if available, very expensive.

Throw the slightly more affordable Saint-Joseph and Crozes-Hermiatge into the fray, and you have a quintet of Syrah superlatives—the global benchmark for this richly expressive varietal on which the fortunes of Northern Rhône have been made … and lost.

Northern Rhône: Etched into the Mountain

The vineyards of Northern Rhône may be the oldest in France, but one thing is certain: Harvesting them ages the workforce. The terraced hillside sites are so steep that the grapes sometimes have to be lowered by pulley, like on a ski slope. It’s said that, in order to make a commercially viable product on sites with sufficient sunlight to fully ripen grapes, you have either to inherit an established right-bank vineyard or produce a wine so good that you can charge an exorbitant price.

Indeed, the most famous producers of the Northern Rhône are family enterprises; these are wineries that vinify grapes they grow, but also purchase fruit from vineyards along length of the entire Rhône valley. The smallholders are the ones who put the sweat equity into these demanding sites, and traditionally, only a handful of them have bottled under their own labels.

This is beginning to change as ambitious newcomers have entered the foray as grower/producers and, at least among those who have been up to the test, have improved the overall quality of the appellation.

Northern Rhône Wines: Syrah’s Reign Over the Unyielding Slopes

In the Rhône, Syrah is such an aristocratic grape that it has its own disease: ‘Syrah Decline’ reared its ugly head in 1993, and causes vines to wither and sometimes die; its cause remains unknown.

On a more salubrious note—and equally interesting—much of the top Rhône wines you may consider 100% Syrah are actually made from a clone called Sérine, most being massale-selections from field cuttings. Sérine is not identical to Syrah, in the field or on the palate; it’s more than likely a mutated and evolved version that seems restricted to Northern Rhône. It is also more savory than many contemporary Syrahs, and it is this quality which has induced winemakers to highlight this quality above all. Côte-Rôtie has traditionally blended a portion of Viognier into their Syrah-based reds to impart floral overtones that may not match this popular swing toward meatier Northern Rhônes.

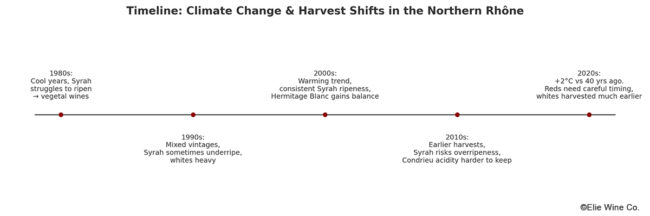

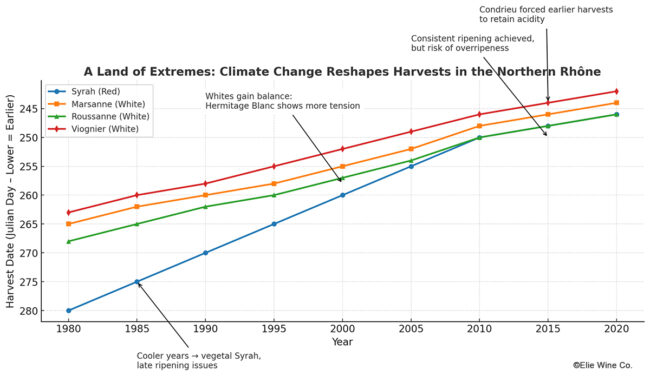

A Land of Extremes: Climate Change Reshapes Syrah’s Harvests in France’s Steepest Vineyards

The terraced vineyards on the cliffs overlooking the Rhône River have always challenged wine growers on multiple fronts. The free-draining soils makes adequate rainfall a must and the Mistral winds exacerbate drought during dry spells by stripping moisture from the vines, forcing growers to plant cover crops to retain soil moisture; others experiment with mulching or adjusting canopy height to shield grapes from sunburn.

Add to that the issue of ripening Syrah at high altitudes: In years without adequate sunshine, grapes failed to reach phenolic ripeness by harvest times that are inherently limited by mountainous weather conditions. As a result, during off years, the wines of Northern Rhône tend to be vegetal, with distinct hard edges.

Enter climate change, bringing with it both heightened aggravations and surprising consolations. Over the past 40 years, average temperatures have risen by more than 2°C in the region—so much that Syrah now generally ripens without fail. Harvests must be timed carefully to avoid overripe grapes, which produce flabby wines without Northern Rhône’s customary taut acidity and pepper edge.

Another consequence of climate change is the improvement it has brought to white wines. Marsanne, Roussanne and Viognier welcome extra warmth, become riper earlier, before their critical acids begins to dissipate. Hermitage Blanc in particular, once heavy in cool years, now shows electric tension alongside richness, while Condrieu, which once had a tendency to get too ripe, is forcing growers to pull forward harvests earlier.

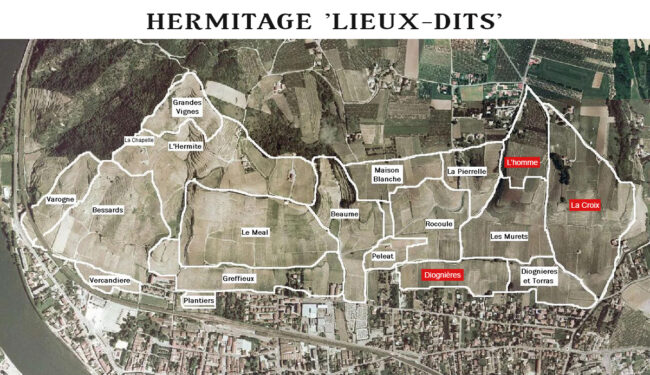

Northern Rhône Lieux-dits: Terroir Distilled to Its Smallest Scale

Lieux-dits are a wine lover’s Google Earth; a satellite view of an appellation focused on a tiny, representative parcel. Not all vineyards have lieux-dits, and among those that do, not all are created equal. In general, it’s a term that refers to a geologically homogenous portion of a vineyard with a self-contained story to tell about its quality or, occasionally, its significance to history. Although lieux-dits are generally not required to be formally registered, they are always named, and that name may occasionally be confused with a producer’s cuvée name, which is often similar. Different appellations have different laws regarding lieux-dits; in Alsace, for example, they are mandatory for Grand Cru AOP labels, whereas in Burgundy, Grand Crus are forbidden from using them.

In the Rhône, lieux-dits are often associated with the region’s top estates, and those that do not have an officially registered place in the French Cadastre are considered ‘les marques’ of their producers. In either case, they are ‘terroir distilled’—an extremely fine-tuned expression of an individual location. To recognize one is to recognize that within the sprawling Rhône there exists an almost microscopic essence that only a lieu-dit can reveal.

Hermitage: Syrah in Its Grandest

Hermitage, one of France’s most reliable appellations, is a pipsqueak that carries a big stick—both its reds and white wines are long-lived and full-bodied. The 345 acres of vineyards entitled to wear the name ‘Hermitage’ are located on a granite hillside facing south and overlooking a short section where the river Rhône flows west to east rather than north to south.

This orientation means that the grapes benefit from the maximum amount of sunlight throughout the day.

Due to slope erosion, Hermitage topsoil is relatively thin compared to that on the valley floor. However light, there are a wide variety of soil types, ranging from sandy gravel in the west, to rockier areas higher up and limestone in the center. As intense Rhône sunshine warms the hillside during the day, the granite bedrock stores this heat, encouraging the grapes to ripen more fully than those in less-exposed sites.

The effect of the local terroir is most pronounced on the western side of the hill where it is steeper than the east and enjoys prolonged exposure to afternoon sunshine.

Jean-François Jacouton

The Hand of the Revivalist

Many vignerons tout their studies abroad, but Jean-François Jacouton is proud to champion his apprenticeship at Domaine Courbis at the southern tip of Saint-Joseph.

“Still,” he maintains, “It was my experiences in Savoie that taught me the value of brining mineral freshness to the wine.”

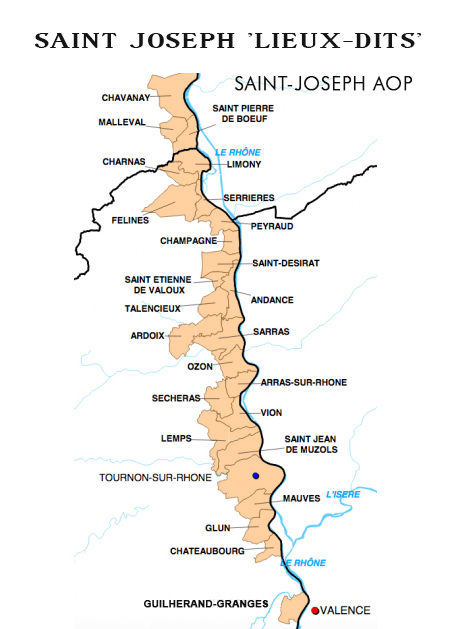

In 2003, Jacouton took over his grandfather’s acres in a few miles north of Tournon, a city that backs into the hills surrounding the Rhône Valley. In 2010, he began domain bottling. His Saint Joseph holdings include older vines in lieux-dits Les Goutelles, Verset Est Paradis, and Tinal, responsible for the stunningly rich Saint Joseph Rouge labeled Pierres d’Iserand.

Jean-François Jacouton

Dedicated to lutte raisonnée farming using horses and hand plowing, Jean-François spends spending almost all of his time among the vines.

“We are in process of reconstructing old stone terraces in areas that returned to forest following phylloxera,” he says. “This commitment to the land is the hallmark of my approach. I strive for classic, old-school reds, but emphasize cleanliness and precision. This is achieved through careful selection in the vineyards, and in the cellar, vinification and aging are in cement, amphora, demi-muids, and larger foudres fermented parcel by parcel and by using an overage of only 20% new wood.”

Jean-François Jacouton, 2021 Hermitage ($82)

Jean-François Jacouton, 2021 Hermitage ($82)

100% Syrah grown on limestone sand and clay from older vines in the lieux-dits Diognières, L’homme and La Croix. The harvest is entirely destemmed with pigéage and pump-overs for 27 days followed by aging in French oak barrels for 14 months. The wine shows classic aromas of graphite, bacon fat, roasted spice and blackberry, all wrapped in a brilliant minerality.

Saint-Joseph: Syrah Finds Its Middle Voice

Unlike Hermitage, St-Joseph covers a lot of territory and multiple terroirs; it encompasses 26 communes and stretches from Chavanay in the north to Chateaubourg in the south, roughly 30 miles in length. The reds from the region can be light for Rhônes, a result of soils containing less granite and vines that face east rather than south. But in strong vintages, they are spectacular.

80% of the wines made in Saint-Joseph are Syrah; only a minuscule quantity—a tenth of one percent—contain any other red wine grape. White wines makes up two in ten bottles of Saint-Joseph’s production and are based on Marsanne and Roussanne, blended or as stand-alones. These wines are dry, with honeyed, floral aromas and balanced weight and acidity, in marked contrast to the sweet Muscat de Beaumes-de-Venise wines from the southern Rhône and the heavier Viognier-based wines of Condrieu and Chateau-Grillet.

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Pierres d’Iserand’, 2020 Saint-Joseph ($35)

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Pierres d’Iserand’, 2020 Saint-Joseph ($35)

100% Syrah from old vines in the lieux-dits Les Goutelles (at a thousand feet elevation), Verset Est Paradis (at 600 feet), and Tinal (at 1200 feet). The grapes are 30-40% whole-cluster fermented with pigéage for 24 days and aged in demi-muids for 15 months. The wine offers a nice balance of fruit and spice, with plum notes alongside dried thyme and wild raspberry; on the mid-palate, you’ll taste smoked meat and olive tapenade, all complemented by refreshing acidity.

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Chemin de Sainte-Épine’, 2019 Saint-Joseph ($46)

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Chemin de Sainte-Épine’, 2019 Saint-Joseph ($46)

100% Syrah from old vines in the historic lieu-dit of Sainte-Épine, perched above the village of Saint-Jean-de-Muzols. Vinification is 30% whole clusters for 24 days, with pigéage and rémontage, followed by aging in new and used oak barrel 16 months. Structured and taut, the wine is loaded with concentrated flavors of wild berries and plum compote with subtle toasted notes and silky tannins.

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Chemin de Sainte-Épine’, 2019 Saint-Joseph ($99) 1.5 Liter

Jean-François Jacouton ‘Chemin de Sainte-Épine’, 2019 Saint-Joseph ($99) 1.5 Liter

The larger format of this wine from 2019 is ideal for cellar storage, which slows and mellow the aging process, likely for many years.

Domaine Jolivet

The Saint-Joseph Upstart

‘St. Joe’—with its rolling granite hills on the west side of the Rhône River—is an amazing discovery. It offers the best of Rhône hillside fruit, vinified by masters of the vine working outside the pressure of the spotlight, for a fraction of the price of the more famous estates in Côte-Rôtie and Hermitage.

Among the young vignerons who are making a vinous mark in the region is Bastien Jolivet, who tends working his family’s vineyards in the hamlet of Saint-Jean-de-Muzols, just north of the birthplace of the appellation in Mauves. When Bastian returned from various internships locally and abroad (Domaine du Monteillet in Condrieu and further afield in New Zealand and South Africa), he convinced his parents to stop selling the fruit from their 26-acre vineyard to the local cooperative and bottle their own wine. This was 2014; since then, Domaine Jolivet in general—and Bastien in particular—have hauled in considerable praise, culminating in Paris with the award Grand Prix Discovery of the Year 2020 by La Revue du Vin de France for best new winemaker.

Bastien Jolivet, Domaine Jolivet

As always, the land represents the soul of the passion. Bastien says, “My goal is to work towards a complete organic certification, and in the meantime, most of our field work is handled organically. The steepest grades, of course, are the hardest to assure pure organic cultivation. All of our little plots run up the hill of Saint-Jean-de-Muzols, which often makes hand-picking a necessity. In the cellar, all fermentations are done spontaneously and aging is done in combination of 228-liter barrels and 600-liter demi-muids, nearly all used. The assemblage is done just before bottling with some time for the wines to knit together. The wines are not fined and only filtered minimally with SO2 kept to a minimum.”

2018 Domaine Jolivet ‘Cuvée 1907’, 2018 Saint-Joseph ($70)

2018 Domaine Jolivet ‘Cuvée 1907’, 2018 Saint-Joseph ($70)

Named after the year in which the vines were planted, it is unlikely that you can find a more intense wine from any Rhône vineyard as old and at such a reasonable price: This is required sipping for anyone curious as to the sort of wine super-old Syrah can produce. The grapes are 100% whole-cluster fermented in stainless steel, then aged in ten-year-old demi-muids to best reflect the concentration of the fruit. It shows dark bramble berries, white pepper and blood orange zest.

Matthieu Barret

(Domaine du Coulet)

The Playful Radical

Matthieu Barret had an interesting plan when he took over Domaine du Coulet: To create a playful range of wines using serious technique. The success of the adventure can be gauged by how coveted his wines are, considered among the most accessible natural wines in France.

A 7th generation vigneron, Matthieu farms the vineyards that grandfather planted after WWII, intending to sell to some of the best-known producers in the Northern Rhône, including Chapoutier and Delas. In 1998, at the age of 23, Matthieu took over the family’s 25 acre vineyard in Cornas.

Matthieu Barret, Domaine du Coulet

Of his philosophy, he says, “I have always believed that the vine is happier in a wild environment. So, we have created ‘green spaces’ around the farm, digging watering holes to nourish a diverse ecosystem of vines, forest, meadow, and woodland. To further this way of thinking, I no longer use machines, replacing them with mules, horses and manual labor. Also, in a pursuit of purity and expression, I radically changed the customary vinification process by utilizing concrete eggs rather than oak.”

Currently, Matthieu creates an array of wines from leased organic and biodynamic vineyards throughout Rhône, and through trial and error, found the formula to express the unique nuances of each micro-terroir. He believes that his portfolio not only expresses the spirit of the land, but his own.

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘D86’, 2020 Saint-Joseph ‘natural’ ($48)

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘D86’, 2020 Saint-Joseph ‘natural’ ($48)

A punchy and classically-lined Saint-Joseph, farmed biodynamically and vinified with whole-cluster fermentation and aging in a mix of 10 hectoliter terracotta pots and concrete vats. The wine is bottled unfiltered, with minimal sulfur additions. It displays wild blueberry and blackcurrant notes shored with up subtle spices and a touch of licorice.

Crozes-Hermitage: Syrah in Its Most Approachable Expression

Crozes-Hermitage is the largest of the Northern Rhône appellations, but it labors in the shadow of its storied namesake Hermitage without pretentions of equality. Price reflects that, of course, and the wine itself does hold at least some measure of the magnificence found in its massively rich, long-lived neighbor. The wine-growing region has a continental climate distinct from the Southern Rhône, and its sheer size adds to the diversity of its terroir. Soils south and southwest toward Gerans largely consisting of granite and clay, while Tain-l’Hermitage is primarily made up of rocks, sand, and clay. The flatter topography in the southern Crozes-Hermitage area is primarily alluvial soil due to Rhône river deposits.

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘Et La Banière…’ , 2021 Crozes-Hermitage ‘natural’ ($40)

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘Et La Banière…’ , 2021 Crozes-Hermitage ‘natural’ ($40)

Et La Banière originates on the well-drained clay/limestone in Les Croix. In line with his biodynamic philosophy, Matthieu Barret pampers each Syrah vines organically and carefully controls yields. Maceration and fermentation is done on indigenous yeasts with pump-overs pumping concrete vats. The wine shows dried cranberry, pie spices and melting tannins that will become more silken with age. Some tasters have suggested a slight fizz to this wine, which is likely the result of the natural process which eschews the use of sulfur.

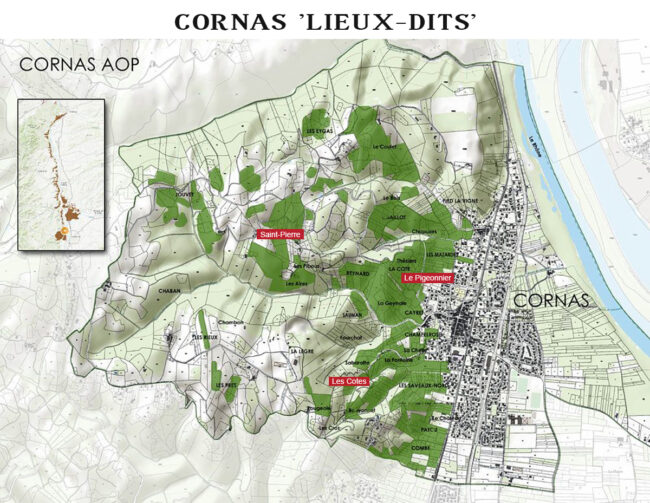

Cornas: Syrah Unbound

At just under three hundred acres, Cornas is even smaller than Hermitage; it’s smaller than some single estates in Bordeaux. It produces only red wines made exclusively from Syrah—a variety that ripens more easily here than nearly anywhere else in Northern Rhône. Celtic for ‘burnt earth,’ Cornas wines—in homage to the name or vice versa—often showcase smoky notes with deep, earthy tones. Once considered ‘country wines’ of value only to those who favor rusticity, the reputation of Cornas has surged in recent vintages, making it one of the most sought-after wines in France.

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘Brise Cailloux’, 2020 Cornas ‘natural’ ($89)

Matthieu Barret (Domaine du Coulet) ‘Brise Cailloux’, 2020 Cornas ‘natural’ ($89)

Brise Cailloux—the ‘Broken Stone’—comes from 50 individual micro-parcels. It spends it first year 50% used oak barrel and 50% concrete eggs, then is moved to concrete eggs for the second year. The wine lusty, yet gentle, with notes that are as complimentary as they are contradictory: Blackberry, violet, lavender, raw meat and blueberry. Accessible now, but with obvious cellaring potential.

Domaine Johann Michel

A Natural-Born, Self-Taught Vigneron

Give a man a bottle and he’ll drink for a day; teach him to make wine and he’ll drink for a lifetime. Still, there is something in the spirit of the man who figures it all out for himself that excites us even more.

Johann Michel developed a passion for fine wine while tasting old vintages with his grandfather, and from there, taught himself the art of vinification. Today, with his wife Emmanuelle, he works 14 acres spread between three Rhône AOP’s. This includes a scant acre in Saint-Joseph planted entirely to Syrah, two-and-a-half acres in the extreme south of Saint-Péray planted to Marsanne and Roussanne, and his most celebrated wines made from lieux-dits in the steep, granite infused slopes of Cornas.

Johann Michel

Michel may be self-taught, but the effusive praise for his product is very much the domain of experts. In what may be the most hyperbolic wine review I’ve ever read, critic Jeb Dunnuck (Northern Rhône: 2019s From Bottle, February 16th 2022) wrote: “The Cornas from Johann Michel is a majestic, full-bodied, incredibly seamless beauty that does everything right, showing the ripe, sunny style of the vintage and bringing ample fruit, richness and power with incredible focus as well as purity and freshness. It will evolve for 15 years or more, and I doubt it will ever close down. Those who like flawlessly balanced Cornas should back up the truck for this sensational wine.”

Domaine Johann Michel ‘Cuvée Mère Michel’, 2020 Cornas ‘Les Côtes’ ($149)

Domaine Johann Michel ‘Cuvée Mère Michel’, 2020 Cornas ‘Les Côtes’ ($149)

‘Mother Michel’ refers to Emmanuelle rather than Johann’s mom; we’ll leave further interpretation to Freudians. The wine was first introduced in 2016 and is not produced every year; it is Selection Massale—the replanting of new vineyards with cuttings from exceptional old vines—in this case, from the 1947 Yves Cuilleron vineyard at Chavanay. Les Côtes is a south-facing lieu-dit sits at an altitude of 900 feet and here produces an intense nose of black fruit, spices and wood smoke. On the palate, the wine is meaty and crisp with bright plum and anise, showing the sweet opulence of Syrah fruit.

Domaine Jacques Lemenicier

Thirty-Two Vintages on the Edge of Cornas

From tragedy to triumph! At the age of 18, when a vineyard-owning family member suffered a car accident, Jacques Lemenicier decided to drop out of high school and become a winemaker. Taken under the wing of Alain Voge, proprietor of the much-heralded eponymous winery in Cornas, Jacques spend ten years training under Alain, learning the vines, borrowing equipment, figuring out his own pathway. Today, he makes two wines; a Cornas from a 7-acre vineyard that perching precariously on a mountain slope and a 9 acre property that grows Marsanne and Roussanne for his steely St. Peray.

Jacques Lemenicier

With 32 vintages under his belt, Lemenicier’s experience with these rocky, challenging terrains is paying off in an accessible, affordable, and terroir-expressive collection.

Domaine Jacques Leménicier, 2019 Cornas ($60)

Domaine Jacques Leménicier, 2019 Cornas ($60)

100% Syrah from two markedly different sites, 65% from the Le Pigeonnier vineyard just outside the village in line with the church, and 35% from Saint-Pierre, ancient Cornas vineyard that dates back to antiquity, with its first stone walls believed to be of Roman origin. The wine is lively, offering spice-tinged aromas of blackberry liqueur that pick up floral and incense nuances with air. Subtly chewy and focused on the palate with spice cake notes braced by a core of juicy acidity. Steadily building tannins resolve in a long, sappy finish.

Côte-Rôtie: Syrah’s Most Eloquent Form

Rolling above the town of Ampuis, the roasted slopes of Côte-Rôtie have several distinct personalities, one most suitable for wine, the others, less so. Only the south and south-east facing hillsides on right bank of the river are worth the discomfort of cultivating and picking, while those to the south—collectively known as the Côte Blonde—produce similar but earlier drinking wines than those produced on the Côte Brune to the north (although traditionally, the wines from these areas have been blended).

Bernard Burgaud

A Singular Côte-Rotie, Bridging Father’s Roots and Son’s Refinement

If you are going to make a single wine, might as well make it superlative. Such is the case with Bernard Burgaud, who produces about a thousand cases of Syrah per year from twenty-two acres of Côte-Rôtie vineyards, planted across several lieux-dits, the majority of which are in Les Moutonnes and Côte Blonde.

Pierre Burgaud, Bernard Burgaud

Bernard began bottling his wine in 1982. As of 2019, his son Pierre continues the family’s legacy as the winemaker for the domain. “In a nod to the estate’s blend of traditional and modern techniques, all our vineyards carry the Haute Valeur Environnementale sustainability certification,” says Pierre. “We vinify without stems, and the wines age in 20% new barriques for 15 months. Our goal is classic, well-balanced wines that taste of black fruit and olives with earthy and rustic flavors. They are meant to be aged, developing into elegant wines.”

Bernard Burgaud, 2018 Côte-Rôtie ($72)

Bernard Burgaud, 2018 Côte-Rôtie ($72)

100% Syrah, destemmed, fermented on natural yeasts and aged for 15 months in French oak before bottling, 20% new. A strikingly herbal nose with juniper and thyme followed by clarity of fruit, with cherry, black currant and plum alongside a smoky, meaty midpalate.

Domaine Guy Bernard

Terroir and Tradition

Frederic Bernard, owner of Domaine Guy Bernard, has his fingers in a couple of very different fruit pies, one Syrah and the other Viognier. Yet he manages to combine the two (a much smaller percentage of Viognier, obviously) to create his iconic Côte-Rôtie.

Domaine Guy Bernard (Photo by Frédéric Boulant)

The estate has been in the Bernard family for years. Located in the Tupin-Semons commune, the estate produces Condrieu as well as Côte-Rôtie .

With 630 acres and 73 named parcels in the communes of Ampuis, Tupin-Semons and Saint-Cyr-Sur-Le- Rhône, Côte-Rôtie has a semi-continental climate, dry and hot in the summer, with mild autumns and harsh winters, with regular precipitation throughout the year.

Domaine Guy Bernard, 2019 Côte-Rôtie ‘Côte Rozier’ ($65)

Domaine Guy Bernard, 2019 Côte-Rôtie ‘Côte Rozier’ ($65)

Côte Rôzier is an old lieu-dit in Ampuis planted in the 1950s by Max Pouzet. The soil is composed of micashistes. 100% Syrah, these grapes were 100% de-stemmed, fermented and macerated over three weeks and completed by daily pumping over and punching down. It matured over 22 months in 400 liter barrels of which 25% were new. The wine shows an intense nose of crushed strawberry and blackcurrant behind a spice box of anise and cinnamon, with a sweet caramel undertow.

François & Fils

An Unexpected Path to Côte-Rotie

The François family paints an interesting portrait—their main occupation is farmhouse cheese making made using milk from their herd of cows. Wine appears to have begun as an afterthought, and even today, they sell all but their finest grapes to négociants.

François & Fils

Yoann François was the main catalyst in expanding the family’s wine label; of the ten acres they own, he champions their Côte-Rôtie which is made using grapes from three south-facing parcels, ‘Les Rochains’, ‘Rozier’ and ‘Le Bourrier’, accounting in total for account for about 3.7 acres. All three lieux-dits are located in the ‘Côte Brune’ region where vineyards are very steep and soils are composed of mineral-rich mica-schist—a good base for the 30-year-old vines of Syrah and Viognier. The vines are planted at a density of 8,000 to 9,000 per hectare and yields are 35 to 40 hectoliters per hectare.

François & Fils, 2019 Côte-Rôtie ‘Rozier’ ($81)

François & Fils, 2019 Côte-Rôtie ‘Rozier’ ($81)

Rozier, in the Côte Brune, offers a perfect south-west exposition and vines around fifteen years old. The wine shows sunbaked earth and iron behind plush, plump notes of cassis balanced by a zesty spine of acidity and finishing long with hints of licorice and chocolate.

François & Fils, 2019 Côte-Rôtie ‘Les Rochins’ ($104)

François & Fils, 2019 Côte-Rôtie ‘Les Rochins’ ($104)

Les Rochins is a very steep parcel next to La Landonne and Rozier and folded into schist soils with iron and clay, producing dark, full-bodied wines that a benefit with some bottle age. This one shows ripe black cherries, incense, brambly blueberries and roasted meat along with loads of ultra-ripe tannins.

Domaine Clusel-Roch

Preserving the Rare Sérine of Côte-Rotie

Sérine—the low-yielding Syrah clone referred to as the rarest and most precious massale selection of Syrah by winemaker Stefano Amerighi—finds serene ground in Verenay, the northernmost village in Côte-Rôtie. Domaine Clusel-Roch, currently run by Gilbert Clusel, his wife Brigit Roch and (since 2009) their son Guillaume, contains nine acres of Sérine planted in 1935 by Gilbert’s grandfather; an acre of this is situated in a lieu-dit known as ‘Les Grandes-Places.’ All subsequent plantings have been massale selection from that vineyard, a rarity in the region as higher yielding material became more prevalent.

The Clusel family were also pioneers of the organic movement as they converted fully in 1990. Says, Guillaume Clusel: “The first time you set your eyes on the hills of Côte Rôtie, it is impossible not be overwhelmed with their beauty. The cliff-like granite hillsides seem to have burst from the Earth with vigor and violence. Only the truly dedicated would decide to make their living there. No tractor on earth can plow these vineyards—everything has to be painstakingly done by hand.”

Guillaume Clusel, Domaine Clusel-Roch

Today, the estate produces cuvées under the Côte-Rôtie, Condrieu, Côtes du Rhône, Coteaux du Lyonnais and Vin de France appellations and, since 2017, has had his grape distilled into marc, teaming up with his sales manager Gaëlle Bonnefond. The pair, friends since childhood, have also developed a range of beer under the name La Brasserie d’Ampuis.

Domaine Clusel-Roch, 2014 Côte-Rôtie ‘Les Grandes Places’ ($199)

Domaine Clusel-Roch, 2014 Côte-Rôtie ‘Les Grandes Places’ ($199)

2014 was a vintage in which only top producers excelled, and only those wines from top sites. The southeast-facing hillside vineyard Les Grandes Places, with its mica-schist soils, certainly qualifies. The wine, with a decade under its belt, offers layers of jasmine, lavender, baking spices, clove, pepper, smoked meat damp tobacco notes (largely tertiary) but retains a vibrant freshness with blackberry and dark cherry at the forefront.

Christine Vernay

(Domaine Georges Vernay)

The Dame of Côte-Rotie

Few winemakers can claim to have achieved wine scores of 100 points, and even fewer can be credited with saving an appellation and a grape variety. Meet the Vernay family: Founded by Francis Vernay in 1937 in the heart of Condrieu, his efforts were crucial in establishing the official Condrieu appellation in 1940. Francis was succeeded by his son Georges, who played a key role in defining the geographical boundaries of Condrieu and is honored for saving the appellation—which grows Viognier exclusively—from extinction.

In 1996, when her brothers showed little desire to take over the family estate, Georges’ daughter Christine came on board as winemaker and General Manager of the estate and is now considered one of the great winemakers in France; several of her wines have recently been awarded the coveted 100/100 in top wine publications. Sadly, Georges Vernay passed away at the age of 92 in 2017.

Christine Vernay, Domaine Georges Vernay

Under Christine’s direction, the fifteen-acre estate expanded their lineup by introducing a new wine from the St. Joseph appellation, La Dame Brune. Their best vines are planted on steep, hillside terroirs with granite and sandy soils. All work in the vineyards is organic and the winery was certified organic in 2019.

Christine says (with pride rather than bitterness), “Twenty years ago, it was rare for women to take over a wine estate, so I wasn’t even considered as a future manager. As the daughter of the so-called Pope of Condrieu who believed in the potential of the Viognier white grape variety from the 1970s, I only started working on this project at the age of 39. My father had saved the Condrieu appellation, pinning his hopes on the vineyard rather than cherry plantations or the cultivation of Ratte potatoes and peas, which were favored by many farmers at the time.”

Christine Vernay (Domaine Georges Vernay, 2017 Côte-Rôtie ‘Maison Rouge’ ($208)

Christine Vernay (Domaine Georges Vernay, 2017 Côte-Rôtie ‘Maison Rouge’ ($208)

From a selection of vines planted in the 1950s; the lieu-dit is called Maison Rouge. 100% Syrah, with 30% whole-cluster fermented and matured in 20% new oak. Vibrant and exotic, with intensely perfumed blackberry and violate aromas complemented by Asian spice and smoke along with salty olive and a focused finish in which the minerality emerges.

Domaine Stéphane Ogier

Côte-Rotie, Shaped with Burgundy Precision

Rooted in Ampuis for seven generations, the Ogier family is blessed with some truly remarkable soil. Under the direction of Stéphane Ogier, the estate manages 27 acres in some of the top Côte-Rôtie terroirs—Lancement, Côte-Rozier and La Vallière. Among the ironies inherent in having seen so much change in the region is that back in the 1950s, the family’s apricots sold for more than their grapes.

In the past twenty years, the winery has grown from producing 15,000 bottles annually to more than a quarter million in 2022, and is widely regarded as a reference point for the appellation.

Stéphane Ogier

Having decided at the age of six to pursue winemaking, Stéphane Ogier first studied viticulture and oenology in Beaune and then did practical trainings with some of the best winemakers in Burgundy and abroad. During this time, he grew his philosophy of winemaking and his laser-like focus on terroir and now farms 12 individual parcels in Côte-Rôtie as well as others in Condrieu, Côtes du Rhône and Vienne.

Of particular interest is his holding in Collines Rhodanienne, of which Stéphane says: “It’s the same land as Côte Rôtie but not in the appellation. My first vintage was 1991, and the wine is made the same way as the Côte Rôties.”

Domaine Stéphane Ogier ‘Réserve’, 2015 Côte-Rôtie ($153)

Domaine Stéphane Ogier ‘Réserve’, 2015 Côte-Rôtie ($153)

First produced in 2012, Ogier ‘Réserve’ is primarily Syrah with a touch of Viognier, and originates in 11 different lieux-dits including Bertholon, Cote Bodin, Champon, Lancement and Vialliere; it’s 65% Cote Brune and 35% Cote Blonde. The wine has matured nicely, with rich spice, licorice and sweet cherries deepening behind earth tones and tannins that have mellowed into an exotic silkiness.

Domaine Stéphane Ogier ‘Le Belle Helene’, 2015 Côte-Rotie ($530)

Domaine Stéphane Ogier ‘Le Belle Helene’, 2015 Côte-Rotie ($530)

Power, concentration and refinement in a glass; everything about this wine is serious. It’s named for Ogier’s mother, not a lieu-dit—it comes from his Côte Rozier vineyard. Licorice, black raspberry and smoke on the nose, with cherries, rocks, stones and plums on the palate with blood and iron on the finish.

Collines Rhodaniennes IGP: A Wider Canvas for Northern Rhône Winemakers

‘IGP’ is the Europe-wide equivalent of ‘Vin de Pays’, a classification that focuses on geographical origin rather than style and tradition, giving winemakers greater stylistic freedom than ‘AOP’. Collines Rhodaniennes is in the northern Rhône Valley, and covers an area from Lyon to Montélimar and includes some of southern France’s most famous AOP appellations, including Côte Rôtie, Condrieu and Hermitage.

Domaine Stéphane Ogier ‘La Rosine Syrah’, 2018 IGP Collines Rhodaniennes ($38)

Domaine Stéphane Ogier ‘La Rosine Syrah’, 2018 IGP Collines Rhodaniennes ($38)

An exquisitely detailed, vineyard-designated wine from a steep-pitched, granite-rich parcel two miles from the famed Côte Blonde. La Rosine is said to be Stéphane Ogier’s ‘secret weapon’ in his vineyard-specific arsenal. All the pedigree of a Northern Rhône powerhouse without the price tag; it blends scents of anise, black olives, cola and plums, revealing substantial complexity in the full, fruit-centered body.

Christine Vernay (Domaine Georges Vernay) ‘Fleurs de Mai’, 2019 IGP Collines Rhodaniennes ($33)

Christine Vernay (Domaine Georges Vernay) ‘Fleurs de Mai’, 2019 IGP Collines Rhodaniennes ($33)

A classic early-drinking Syrah, not necessarily built for the long haul, but rather, to be showcased in its sensuous and silky youth. From 50-year-old vines planted adjacent to Condrieu, (hence, a IGP Collines Rhodanienne designation) fermented in stainless steel and barrel, then aged eight months in wooden vats. The wine is filled with luscious black cherries and new leather with spice and pepper in the foreground.

Notebook …

The Stalk Talk of Winemaking: To Stem or Not to Stem

When you see ‘whole cluster fermentation’ in a winemaker’s description, he or she is referring to a technique where entire grape bunches, including stems, go into the fermenter. In other words, the wine grapes do not go through a destemmer-crusher to destem individual berries and crush out the juice.

Advocates of whole cluster fermentation assert it produces wines with more complexity, and with additional herbal and spice flavors, toning down high acidity while adding tannic structure. The practice may be seen frequently with Pinot Noir in Burgundy and Oregon’s Willamette Valley, and in Northern Rhône, winemakers claim that it enhances the savory qualities and peppery notes of Syrah. Where grapes are fully ripened, as they tend to be in Cornas, stems bring significant tannin to the party, and so the wine requires intense fruit for balance. But by binding chemically with tartaric acid, stems tend to lower acidity in the process, so a careful balancing act must be maintained. It should be noted that the more mature the stems, brown and woody instead of green, the more subtle the influence.

Northern Rhône: A Vintage Chronicle

2021: Frost, Humidity and Storms Yield Elegant Wines

Like most of France in 2021, the Rhône Valley suffered from a difficult growing season. The winter and early spring was relatively dry, although temperatures were so mild that there was premature vine growth. This was followed by a series of hard frosts that dramatically cut yields, and the bunches that remained intact were subject to disease during an unusually humid summer. Cloudy skies prevented even ripening and brought devastating storms in July and August. The grapes were slow to reach phenolic ripeness and, as a result, the harvest was later, longer and slower than normal. The wines have good structure and acidity and although alcohol was lower than in other years, there was still enough to assure body. For the big red appellations like Saint-Joseph and Hermitage, black and white pepper notes come through strongly, but the wines themselves tended to be more restrained, favoring elegance over bombast. The whites are fresh, elegant and aromatic rather overblown.

2020: Drought, Heat and Early Harvest Ensures Balance

The most notable features of 2020 are beginning to sound like a ‘new normal’: Drought, heat and an early harvest. Gratefully, heavy rains in the previous October, November and December that created reserves the vines could draw from. Rain fell in May and June, although the rest of the growing season was exceptionally dry. Guillaume Sorrel (Domaine Marc Sorrel) went as far as to say that 2019 precipitation saved his 2020 vintage.

The vineyards roused early thanks to warm weather in March, but mercifully there were no spring frosts. Northern Rhône held on to this lead throughout the year, resulting in the earliest vintage since 2003. Warm days were balanced by even cooler nights, which allowed the bunches to ripen gradually and evenly, producing small, healthy and perfectly formed berries. Syrah yielded clean, fresh fruit flavors, silky tannins and refreshing acidity while Northern Rhône whites made from the typically lower acid varieties of Viognier, Marsanne and Roussanne saw enhanced perfume, vibrancy, texture and freshness.

2019: Heatwave Defines a Generous, High-Quality Vintage

2019 marked the fifth consecutive vintage in which the wines of Northern Rhône are rated very good and some, truly exceptional. It was yet another vintage marked by an intense summer heat wave, however, with hardly any other viticultural challenges to contend with most growers able to embrace yet another ‘solaire vintage’ and ushered in a sizable crop of beautifully healthy and balanced grapes.

2018: Hot, Dry Year Yields Ripe and Ageworthy Wines

2018’s ‘en primeur’ Cliff’s Notes: “Very hot and dry, resulting in a plentiful ripe crop. Many wines with low acidity and potent alcohol, but those that could achieve balance made impressive wines.”

In slightly greater detail, both the winter and spring were wet and mild but despite some light rain falling during flowering, it was still reasonably successful. Unexpected rainfall in June did cause some difficulties with mildew and rot, but it was mostly restricted to Southern Rhône. The rot meant many producers had to spray but, unfortunately, a large amount of the crop was still lost. Eventually, the damp weather dried up and a hot, dry summer took its place. By the time it came to harvest, temperatures were high and producers had to work quickly when handling the grapes.

In Northern Rhône, the harvest was shorter than in the south as the grapes ripened rapidly making excessive alcohol a potential issue. Picking began early September and lasted through to the middle of the month. Despite the hot year, the whites still retained a fresh character as well as being concentrated, while the reds ranged from black-fruit powerhouses to friendlier red-fruited wines. Although some wines did suffer a touch from too much alcohol and a lack of acidity, many were successful with interesting characters and capacity to age.

- - -

Posted on 2025.09.04 in Saint-Joseph, Cornas, Côte Rôtie, Hermitage, Brézème, Saint-Péray, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Northern Rhone

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Aligote, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Cinsault, Clairette, Corvina, Counoise, Dolcetto, Erbamat, Ferrol, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Gamay, Garnacha, Garnacha Tintorera, Gewurztraminer, Graciano, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malbec, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marcelan, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montònega, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscat, Natural, Niellucciu, Parellada, Patrimonio, Pedro Ximénez, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Pouilly Fuisse, Pouilly Loche, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Riesling, Rondinella, Rose, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sagrantino, Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Sciacarellu, Semillon, Serine, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Search