The Rise of Terroir in Champagne: Two Standout Producers In Search Of Precise Geography In Two Different Sub-regions (The Many Faces Of Meunier) + Recent Arrival: Clandestin ‘Elegant Champagne With A Burgundian Accent’

‘First and foremost, Champagne is wine.’

Our Champagne mantra over the past few years has been a bit reductionist: While undeniably accurate, it’s a little like saying that, first and foremost, ‘David’ is a hunk of marble or that at its essence, La Traviata is a bunch of notes. What these self-evident truths leave out is the human touch—the x-factor that makes art from the inanimate and beauty from the base.

As France warms with the rest of the planet, new regional wines are coming into focus and former sow’s ear soils are producing silk purse products. This is a paean to nature, of course, and as always, the passion arises from the people, not from the place. Folks like Alexandre and Fanny Heucq, fourth generation artisan winemakers from the grower house Champagne André Heucq and Olivier Langlais, the winemaker behind Solemme Champagne, who advocates simplicity and honesty in his wines.

These are two standout icons from our Champagne portfolio, but more than that, they are the flesh behind the finesse.

The Impact Of Climate Change on Champagne: Heating-up

Global wine production in 2023 was at its lowest in 60 years, and a lot of the decline can be blamed on extreme weather events, many of which have been worsened by climate change. Italy dropped from its position as the world’s leading wine maker due to numerous adverse weather events, including erratic rainfall that triggered downy mildew as well as floods, hailstorms and drought. In 2021—for the same reasons—Champagne saw the smallest harvest since 1957.

Somewhere amid all these clouds is a silver lining known as the Goldilocks Zone, and we may be living within it as we speak. Ripening grapes has always been a primary challenge in Champagne, located near the northern growing zone limit of its three principal grapes, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Meunier. Although the rise in temperature (nearly two degrees between 1961 and 2020) has beneficial effects in the short term, especially at higher elevations, the downsides are legion—earlier budburst makes the risk of frost damage more pronounced, and frost control systems, especially those based on combustion, add to the region’s carbon footprint. Not only that, but warmer days often precede warmer nights, affecting a grape’s natural ability to retain acid, giving Champagne its intangible ‘zing’.

Despite magnanimous efforts to reduce their carbon emissions, including use of bio-based products in the fields and cellars, scrapping much of the mineral fertilizers used in the past and planting of hedges and trees allowing a better absorption of CO2 and storage of carbon in soils, the warming of the region is likely to continue for the foreseeable future—potentially, according to ClimateAi, making Chardonnay and Pinot Noir (and to a slightly lesser extent, Meunier) impossible to grow in the area currently defined as Champagne.

That means we may well be in the midst of a ‘best of both worlds’ phenomenon in Champagne, where the positives still outweigh the negatives and we are able to enjoy riper, richer wine that is today (more often than in the past) of vintage quality. By 2050, who knows?

The Biodynamic Principles: Respecting Earth’s Life Forces

Credit Dr. Rudolph Steiner for codifying the basic principles of biodynamics; his 1924 lecture series to farmers opened a wormhole that integrated scientific understanding with a recognition of an underlying spirit in nature and, indeed, in the cosmos at large. In Cliff’s Notes shorthand, the movement recognizes every farm, garden or vineyard as an integrated organism made up of interdependent elements: Plants, animals, soils, compost, and the classically French view of ‘the spirit of a place.’ Biodynamic farmers listen to the land and work to nurture and harmonize these elements, managing them in a holistic and dynamic way. The goal, whether the crop is grain or grapes, is to develop and evolve a given plot of land as a unique individuality.

These principles are custom made to accentuate terroir, but in Champagne, distinctiveness of location has often taken a back seat to a homogenous blend. As a result, the region as a whole was a bit late to the biodynamic party. The era between 1970 and 2000 may be viewed as cringe-worthy in terms of viticulture; the overuse of pesticides and herbicides and the once-favored fertilizer known as ‘boues de ville’—urban waste—damaged soils even in the most prestigious Grand Cru vineyards.

The biodynamic sun came out at turn of the century, when the Comité Champagne conducted in-depth research into the industry’s environmental impact and launched an ambitious plan, resulting in a 20% reduction in carbon emissions per bottle and a 50% reduction in the use of both phytosanitary products and nitrogen fertilizers. A regional sustainability certification, VDC (Viticulture Durable en Champagne), was introduced in 2014 and today, 15% of Champagne’s vineyards falls under the certification, and ambitions are much higher for the future.

The Mountain, And Then The Valley: The Many Faces Of Meunier

For the trend conscious (as well as the eco-conscious), Meunier, often the odd-grape-out in discussions of Champagne dominant trio of varietal, is enjoying something of a heyday with a growing legion of fans, both for its frost-resistance and its bright, bergamot-tinted profile. Of the planted acres in Champagne, Meunier represents about 31%, or roughly 84,000 acres. In the Marne Valley, however, it dominates, making up more than 60% of the vineyards.

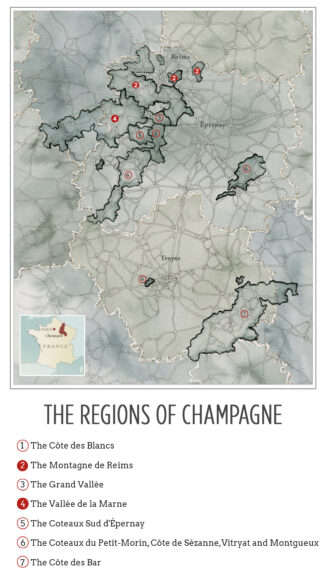

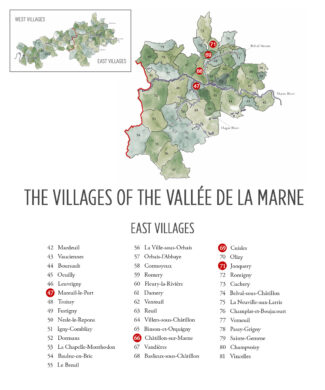

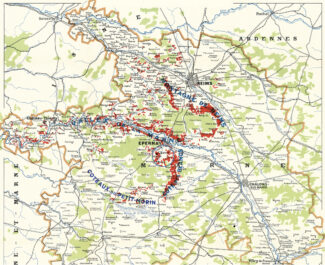

The valley is long—it extends more than sixty miles from the city of Tours-sur-Marne to Château-Thierry, wending thorough two départements, the Marne and the Aisne, all the way to the limits of Seine-et-Marne. As its name indicates, the Marne Valley follows the river through a landscape of rolling hills and small villages. Vines are planted on both banks although those on the north side benefit from a more favorable southern to eastern sun exposure.

The variety of Marne terroirs within its various villages and numerous sub-zones is expansive; in addition, the geology of the soils are more variable in Marne than in other Champagne sub-regions. As a result, the styles of Champagne, even those made mostly or entirely from Meunier, can vary widely. In the Petite Montagne, for example, the Meunier tends to be firmer and more structured, while the wines of the Vallée de la Marne are broader and more ample in build.

Representative of the many faces of Meunier are the artisan producers featured in this week’s selection, Alexandre and Fanny Heucq of Champagne André Heucq (whose mineral-focused Meunier is the result of their unique green Illite soils) and Olivier Langlais of Champagne Solemme, a vigneron who stands out from the pack as a true maverick, making Champagnes using only the year’s wines.

The Villages of The Vallée de la Marne: Coldest Weather in Champagne, Clay-Rich Soils

The most famous villages are located at the eastern end of the valley around the city of Épernay, a ranking that reflects the importance given to the presence of chalk in the soil. Chardonnay and Pinot Noir dominate the vineyards of the eastern end of the region, and the major Champagne houses located here include Billecart-Salmon or Philiponnat in Mareuil-sur-Aÿ, Deutz and Bollinger at Aÿ and Jacquesson in Dizy.

West of Châtillon-sur-Marne, chalk tends to be found more deeply buried in the ground; the topsoil is made of calcareous clay and clay marls. The combination of cold weather and rich clay makes Meunier the grape of choice in this part of the valley and it is here that a new generation of experimental winemakers is deepening their own (and by proxy) our understanding of the varietal.

Fanny & Alexandre Heucq

Champagne André Heucq

In the heart of the Marne valley is the tiny commune of Cuisles (population 150) which happens to be an epicenter for the green illite clay; it is unique to Cuisles and two surrounding villages and it is arguably the terroir where Meunier feels most at home.

According to André Heucq, who—along with his daughter Fanny— specializes in Meunier grown on fifteen acres of estate vineyards, “Green clay retains water better than chalky soils, this type of soil needs less water than classic clay-limestone soils. Generally speaking, the Marne Valley is prone to downpours of rain, and this is where Cuisles’ unique position in the hollow of the valley plays a fundamental role: Showers are much less frequent, so soil and climate are in perfect alchemy for optimum ripening of the Meunier.”

André & Fanny Heucq, Champagne André Heucq

Fanny says that the terroir, so vital to their wines’ purity and elegance, is enhanced by a commitment to biodynamics: “Production that respects the environment reactivates the vine’s natural self-defense mechanisms, allowing us to do away with the use of chemicals and use very low doses of copper and sulfur.”

Among the strictest (and most interesting) of the cosmos-oriented techniques the estate relies on is the ‘500’—a preparation is obtained by fermenting good quality cow manure in the soil over the winter, introduced via cow horns. Fanny explains, “This preparation is aimed at the soil and plant roots. Its name comes from the fact that it contains over 500 million bacteria per gram. The silica from the horn is equally important. It is complementary to and acts in polarity with the 500. It is not aimed at the soil, but at the aerial part of plants during their vegetative period. It can be said to be a kind of ‘light spray’, which can promote vegetative vigor or, on the contrary, attenuate excessive luxuriance. It brings a luminous (crystalline) quality to plants, and reduces their tendency to disease. Not only does it reinforce the effects of sunlight, it also enables a better relationship with the cosmic periphery, with the entire cosmos. This preparation is essential for the internal structuring and development of plants. It promotes vertical plant growth. It makes plants firmer and more supple. It increases the quality and resistance of leaf and fruit epidermis.”

Views From The Right Bank: Meunier Reigns Supreme

Not only an underdog but occasionally an afterthought, growers in Champagne have often planted Meunier vines in areas that will not support the appellation’s noble couple, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Older vines are often found in otherwise marginalized areas, and the grape is not permitted to wear the designation ‘Grand Cru’ even if it is grown exclusively in a Grand Cru village. As a logical result of this elitism, very little Meunier is grown in Grand Cru vineyards and many producers avoid using it in their vintage wines due to its rumored inability to age—a rumor which, incidentally, is unfounded.

As in Bordeaux, the difference between the right and left banks of the region’s dominant river are striking, both in terms of vineyard exposure and soil composition. The Marne is an eastern tributary of the Seine in an area east and southeast of Paris. In Champagne, where it runs west toward Épernay, the right bank sports the valued south/southeast exposure that maximizes sun exposure and aids grape ripening. As with the Right Bank of the Dordogne River in Bordeaux, the Marne’s right bank contains more clay, making it more suited to Meunier than either Chardonnay or Pinot Noir, which may struggle to ripen in the area’s cool, frost-and-fog-prone microclimate.

Champagne André Heucq ‘Héritage’ Blanc de Meunier, Vallée-de-la-Marne Brut Nature ($51)

Champagne André Heucq ‘Héritage’ Blanc de Meunier, Vallée-de-la-Marne Brut Nature ($51)

100% Meunier harvested in 2016/2017 from 30-year-old vines grown in illite-rich plots in Cuisles, Châtillon-sur-Marne, Serzy and Mareuil-le-Port. The wine underwent full malo and spent 48 months on lees; it was dosed to Brut Nature. The nose is nicely spiced with stewed apple and pear with notes of jasmine. A slight lemony bitterness on the finish is a mirror of the terroir. 25,000 bottles made.

Champagne André Heucq ‘Hommage Parcellaire’, 2015 Vallée-de-la-Marne – Jonquery ‘Les Roches’ Brut Nature ($117)

Champagne André Heucq ‘Hommage Parcellaire’, 2015 Vallée-de-la-Marne – Jonquery ‘Les Roches’ Brut Nature ($117)

100% Meunier from younger vines—22 years old—grown in illite in the ‘Les Roches’ lieu-dit in Jonquery. The wine is from the 2015 harvest, fermented ‘en barrique’ and aged three years on lees after undergoing full malo. Dosed to Brut Nature. The wine’s bouquet is of peach and plum with notes of pie crust and almond. The long and pronounced minerality in the finish is indeed an earthy homage to the parcel from which it arises. Only 800 bottles were made.

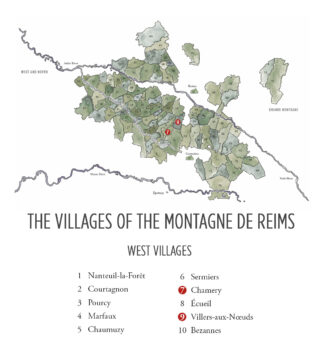

The Montagne de Reims: Grande, Petite, North And The Grand Vallée

Located between Reims and Épernay, the Montagne de Reims is a relatively low-lying (under a thousand feet in elevation) plateau, mostly draped in thick forest. Vines find a suitable home on the flanks, forming a horseshoe that opens to the west.

So varied are the soils, topography and microclimates here that it is not possible to speak of the region in any unified sense. Grande Montagne de Reims, which contains all of the region’s Grand Cru vineyards, covers the northern, eastern and southern slopes of the viticultural area, and Pinot Noir plantings dominate at 57%, followed by Chardonnay (30%) and Meunier (13%). Its vineyards face a multitude of directions, and soil type varies by village, giving rise to a breadth of Pinot Noir expressions, as well as exceptional Chardonnay.

To the west, the Grande Montagne de Reims gives way to the Petite, whose bedrock is chalk, but softer than the chalk found further south on the Côte des Blancs. This sort, called ‘tuffeau’, is an extremely porous, sand-rich, calcium carbonate rock similar to what is found in wine regions of the middle Loire Valley.

In French, the word ‘petite’ often to refers to a ‘lesser’ commodity, but with La Petite Montagne, the reference is to elevation. This lower elevation means warmer weather, even in Champagne’s northerly climate, and in certain villages, the soil contains more sand, making it an ideal environment for growing Meunier.

Meunier accounts for approximately half of the plantings in the Petite Montagne, with Pinot Noir making up 35% and the rest Chardonnay. It is a growing conviction among growers of the modern era that Meunier is a Champagne grape whose time has come, especially as an age-worthy variety.

Emmanuel Brochet of Villers-aux-Nœuds says, “People claim that Meunier ages too quickly, even faster than Chardonnay. I disagree. The curve of evolution is different. Meunier is quick to open and more approachable in youth, but then it becomes quite stable. Chardonnay tends to open later, but old Meunier remains very fresh and lively.”

Olivier Langlais

Champagne Solemme

The name Solemme is a combination of ‘sol’ for the sun, with the addition of a feminine suffix. “My goal,” says cellar master Olivier Langlais, “is to make delicate Champagnes that are bright like the sun.”

La Petite Montagne-de-Reims, to the west of the road between Reims and Épernay, boasts steep slopes and chalky soils, making it the home of some of the best vineyards in Champagne—Savart, Brochet, Egly-Ouriet, etc. Also calling the region home is Olivier Langlais, who farms fifteen acres of organic vineyards in the terroir around Villers-Aux-Nœuds. A true exception in Champagne region, he makes wines using only the product of the harvest year.

His dedication to biodynamics and agriculture according to the cycles of the moon began with the Chardonnay plot in 2009 and finished the transition with his oldest vines of Pinot Noir in 2015. The vineyard is composed of 50% Meunier, 25% Chardonnay and 25% Pinot Noir divided between six villages—five of them Premier Cru. Most of the plots, as is the case of most Petite Montagne de Reims vines, are southeast/east oriented.

Olivier Langlais, Champagne Solemme

“Everything is happening in the exchange between the soil and the grape,” Olivier points out. “That’s why the difference of terroir between all parcels determines variety and process. Villers-aux-Nœuds has a classic chalky soil, bringing a lot of minerality to the Chardonnay and Meunier growing there. Clay-limestone dominates Chamery and Vrigny, with a bit more clay in Vrigny, where Meunier gets better results—clay gives more ‘gras’, or roundness to the grapes. Often not mentioned is the sandy soils of Villedomange and Éceuil, which gives Pinot Noir a concentrated and elegant form.”

Once in the cellar, Olivier is a champion of a hands-off approach. He never chaptalizes and uses only natural yeast from his vineyard. “In the chai, you won’t find any barrels,” he says. “We do not filter, there is no addition of SO2 and all the cuvées spend between 36 to 48 months on the lees as a means of better expressing the terroir. 90% of the time, I don’t do any malolactic fermentation, because I prefer to let the natural minerality shine.”

Varietal Transformation in The Petite Montagne: Meunier Shares Space With Pinot Noir

The western portion of the Montagne de Reim—the so-called Petite Montagne—stretches from Gueux in the north to Sermiers in the south, on the western side of the main road that runs between Épernay and Reims. Although this region has a historical fondness for Meunier, some acres have been replanted to Pinot Noir in recent years, potentially doing a disservice to the vineyards north of Écueil in the villages of Sacy, Villedomange, Jouy-lès-Reims, Coulommes-la-Montagne, Vrigny and Gueux. But the soils here are generally more overtly calcareous than those in the Vallée de la Marne and can contain a high proportion of fossils. In Écueil, there is sand on the lower slopes, acting as a defense against phylloxera, allowing some growers to plant Pinot Noir on the original rootstocks, so this becomes the cultivar of choice.

Champagne Solemme ‘Terre de Solemme’, Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds Brut ($59)

Champagne Solemme ‘Terre de Solemme’, Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds Brut ($59)

Villers-aux-Nœuds is a Premier Cru village in Vesle et Ardre; about half the vineyards are planted to Pinot Noir, with Meunier making up about 30%, and the rest, Chardonnay. Olivier Langlais farms fifteen acres here; the land is relentless hilly and the soil is made up of Cretaceous chalk under a few inches of ‘argilo-calcaire’ topsoil. Disgorged according to the moon cycle (a feature of his brand of biodynamics), ‘Terre Solemme’ is a blend of 55% Meunier, 25% Pinot Noir, and 20% Chardonnay aged three years on the lees. Buttery toast on the nose along with cooked apple and cantaloupe. The palate has an echo of the nose and a nice marzipan richness that drives the mineral finish home.

Champagne Solemme ‘Ambre de Solemme’, 2016 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds ‘La Motelle’ Blanc de Noirs Brut Nature ($99)

Champagne Solemme ‘Ambre de Solemme’, 2016 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds ‘La Motelle’ Blanc de Noirs Brut Nature ($99)

100% Meunier from the ‘La Motelle’ lieu-dit, filled with 50-year-old Massal-selected vines; these grapes were harvested somewhat late and developed a spectacular ripeness. ‘Ambre’ refers to the color, whose slight tint is the result of skin-contact. The nose sets out with fresh apple and a touch of grapefruit and strawberry coming out, with bold acidity reflected in a spine of salinity that balances an otherwise rich and creamy wine.

Champagne Solemme ‘Esprit de Solemme’, 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Brut Nature ($79)

Champagne Solemme ‘Esprit de Solemme’, 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Brut Nature ($79)

2018 was an excellent vintage in Champagne; the crop was large and healthy, rich in sugar and flavor depth, with all three major grape varieties performing well. ‘Esprit de Solemme’, 2018, is equal parts Meunier and Chardonnay drawn from chalky soil in Villers-aux-Nœuds and the clay-limestone hillsides of Chamery. This cuvée shows a lovely bouquet: cream, biscuits, pineapple and toasted nuts. The palate is very dry but stays in balance with cream and salinity through the finish.

RECENT ARRIVAL

The wine world is a churning urn of burning trends, and what catches fire in America is not necessarily the same thing that ignites Europe: The concept of ‘grower Champagne’, for example, often carries more weight here than it does among the Champenois producers themselves. Champagne made in-house from grapes grown on the estate may wear the grower Champagne label, while the majority of Champagne houses purchase grapes as négociants and create signature blends. When a house wears ‘Domaine’ on the label, it is the former; ‘Maison’ generally represents the latter.

Between the two is the micro-négociant, who operates on a smaller scale and often produces high-quality micro-cuvées, controlling production from vineyard to bottling, and focuses on representing individual vineyard sites.

One micro-négociant estate that is capturing attention of both here and in Aube is Champagne Clandestin, a joint venture between Meursault-trained winemaker Benoît Doussot and Aube legend Bertrand Gautherot of Vouette & Sorbée.

Micro-Négociant

Champagne Clandestin

‘Elegant Champagne with a Burgundian Accent’

‘Clandestin’ means exactly what you think it does—something hidden, something to be explored. In this case, it refers to the Aube’s long-overlooked, west-facing parcels of Pinot Noir on Kimmeridgian soils as well as Chardonnay on Portlandian soils above Buxières.

These cuvées represent vineyards that have generally been eschewed in the region; southerly, easterly and southeastern-facing parcels have long been favored in the Aube because they are exposed to more sunlight during day while their western counterparts have never been fully utilized. Both Bertrand and Benoît were convinced that a longer and slower ripening and maturation process could imbue the wines with added complexity and depth. Clandestin is made from 20 acres of cooler, west-facing vineyards, which are farmed organically, certified by ECOCERT and vinified according to the exacting standards for which Vouette & Sorbée is known.

Benoît says, “After pressing, the wine is aged in French oak barrels following closely the training I received in Meursault before moving north to Champagne. This wine should appeal to purists in search of minerality, cut, and precision. Because we insist on harvesting perfectly ripe grapes, which is not generally the case in Champagne, the wines can be bottled with no dosage, giving room for the oceanic terroir to really shine through.”

nv Champagne Clan Destin ‘BORÉAL’ Côte-des-Bar Brut Nature ($79)

nv Champagne Clan Destin ‘BORÉAL’ Côte-des-Bar Brut Nature ($79)

Harvest 2020. 100% Pinot Noir grown on vines between 20-35 years old, fermented and aged in French oak before aging sur latte for 15 months before being disgorged with zero dosage. Earthy aromas of wild strawberries, brioche and toast waft from the flute followed by a delicate mineral crunch. Disgorged July 2022.

Notebook ….

Single Harvest vs. Vintage

In France, under Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) rules, vintage Champagnes must be aged for three years—more than twice the required aging time for NV Champagne. The additional years on the yeast is said to add complexity and texture to the finished wine, and the price commanded by Vintage Champagne may in part be accounted for by the cellar space the wine takes up while aging.

On the other hand, a Champagne maker might prefer to release wine from a single vintage without the aging requirement; the freshness inherent in non-vintage Champagnes is one of its effervescent highlights. In this case, the wine label may announce the year, but the Champagne itself is referred to as ‘Single Harvest’ rather than ‘Vintage’.

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

To be Champagne is to be an aristocrat. Your origins may be humble and your feet may be in the dirt; your hands are scarred from pruning and your back aches from moving barrels. But your head is always in the stars.

As such, the struggle to preserve its identity has been at the heart of Champagne’s self-confidence. Although the Champagne controlled designation of origin (AOC) wasn’t recognized until 1936, defense of the designation by its producers goes back much further. Since the first bubble burst in the first glass of sparkling wine in Hautvillers Abbey, producers in Champagne have maintained that their terroirs are unique to the region and any other wine that bears the name is a pretender to their effervescent throne.

The INAO defines the concept like this: “An AOP area is born of an alliance between the natural environment and human ingenuity. From that alliance comes an AOP product with unique, inimitable characteristics, a product so different that it complements rather than competes with other products, possessing a particular identity that adds further value.”

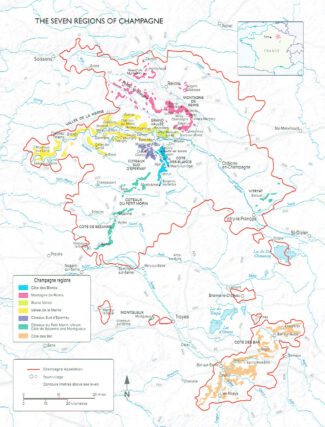

In 1927, the viticultural boundaries of Champagne were legally defined and split into five wine-producing districts: The Aube, Côte des Blancs, Côte de Sézanne, Montagne de Reims, and Vallée de la Marne. The CIVC (Comité Interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne), formed in 1941, decreed that everyone who wanted to plant vines and grow grapes to be used in the creation of Champagne had to be registered, and if you didn’t register back then, there is no out, even now. Originally, grape growing was not a profitable business and was an afterthought meant to utilize chalky slopes where grain would not grow. As a result, many farmers at that time did not register, and today, a tour along the Route Touristique de Champagne, you’ll come across unregistered fields that lie fallow between two registered vineyards.

… Yet another reason why this tiny slice of northern France, a mere 132 square miles, remains both elite and precious.

- - -

Posted on 2024.01.14 in France, Champagne, Wine-Aid Packages

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Aligote, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Cinsault, Clairette, Corvina, Counoise, Dolcetto, Erbamat, Ferrol, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Gamay, Garnacha, Garnacha Tintorera, Gewurztraminer, Graciano, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malbec, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marcelan, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montònega, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscat, Natural, Niellucciu, Parellada, Patrimonio, Pedro Ximénez, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Pouilly Fuisse, Pouilly Loche, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Riesling, Rondinella, Rose, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sagrantino, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Sciacarellu, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Search