‘Mercurey’ Rising: Four Producers Soar in Another Côte Chalonnaise Hidden Gem With Red and White (5-Red & 3-White Sampler $399)

Join us for Saturday Sips

Come as you are; come any time that’s convenient for you during our business hours to sample selection from this week’s selections. Our staff will be on hand to discuss nuances of the wines, the terroirs reflected, and the producers.

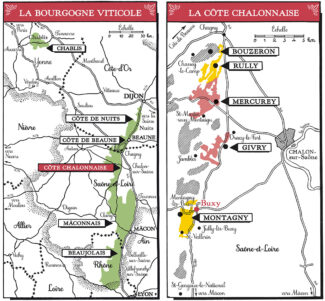

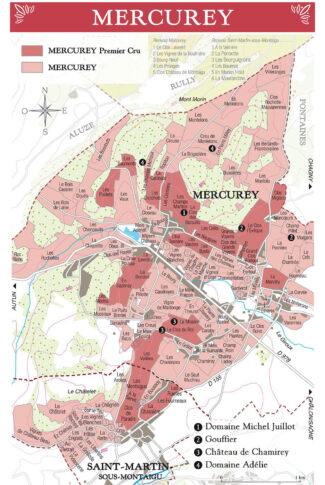

This week, we continue our trek through Burgundy’s ‘fringe’ appellations, moving southward to Mercurey, just below Rully, where the vineyards festoon marl-limestone hillsides that formed in the Upper and Middle Jurassic period. The soils of Mercurey are ideally constructed as an ideal environment for Pinot Noir and the red wines of this region are prized for their complexity and ability to age. Chardonnay-based Mercurey are more rare and much sought out; there are small pockets of terroir in Mercurey that are structured like the best vineyards of the Côte de Beaune.

The package contains eight bottles, both white and red; an ode to the diversity of Mercurey—an appellation that offers among the widest range of expressions in Burgundy.

Exploring Burgundy’s Periphery: Mercurey

Shaped like a vast amphitheater, the vineyards of Mercurey owe their terroir to the hundreds of millions of years they spent submerged beneath a prehistoric sea. Marine sediment gradually built up, forming clay, marl and finally, limestone. This geological diversity has paired with a variety of exposures and altitudes to create a remarkable cradle for wine: Mercurey is the most important appellation in Côte Chalonnaise by far.

The appellation, created in 1936, covers the wines of Mercurey itself plus those of neighboring Saint-Martin-sous-Montaigu. Mercurey is the most prolific of the five Chalonnaise communal appellations, producing more wine than its neighbors Rully and Givry combined. This large output comes from a dense patchwork of vineyards covering around 1600 acres of rolling limestone hillsides. Around a quarter of these vineyards are classified as Premier Cru, accounting for 32 officially recognized and delimited climats; wines from these sites may append their vineyard names to the Mercurey Premier Cru appellation title.

Beating The Heat

2020: Healthy and Ripe, Surprising Levels of Freshness

François Labet, a négociant whose family has lived in Beaune for 300 years, summarizes the 2020 vintage like this: “An intellectually-challenging vintage; the reds in particular defy easy categorization because the impact of that season varied considerably by terroir. Producers had key decisions to make, especially when to pick and that significantly affected both the style and quality of the resulting wines.

And this is because the most notable feature of this vintage was its early and rapid harvest: Many domains began picking the week of August 17th and while August harvests have been frequent in the 21st century (there were none in the prior century), this was for many domains the first time they had not only started, but completed a harvest before the end of August.

The resulting wines (particularly from earlier harvests where sugars were high and acids intact) are remarkable, both for whites and reds. The season was hot and dry, but water tables were healthy from the mild and wet preceding winter.

Beaune and Côte Chalonnaise were particularly fortunate and Chef de Cave Frédéric Weber (Bouchard Père et Fils) describes 2020 as a concentrated and strong vintage: “It reminds me of 2016 for its vibrancy and energy; the wines are voluptuous and structured. A great vintage for the future, like the ‘18s.”

Domaine Michel Juillot

The vineyards of Domaine Michel Juillot spread across the Côte Chalonnaise and Côte de Beaune and include 50 acres of Pinot Noir and twenty-five of Chardonnay. Of the sites, located in twenty individual appellations, half are Premier Cru.

Says fourth-generation winemaker Laurent Juillot: “Between our parcels, we do not differentiate the care we provide. We are convinced that our added value is in the terroir alone. The difference between a Premier Cru, a Village or a Bourgogne generic wine comes from the soil, the earth, the sun and the grape in its environment. We respect them all equally and treat them accordingly.”

Laurent Juillot, Domaine Michel Juillot

Laurent is the grandson of Michel Juillot, and it was with the elder Juillot’s blessing that the estate, under Laurent’s direction, began to move toward sustainable agriculture. As a true gauge of quality, he ferments on native yeasts alone, as he believes that this is the only way to faithfully transcribe into a single-parcel cuvée the true expression of that unique climat. Current production is 180,000 bottles.

Domaine Michel Juillot, 2020 Mercurey Premier Cru Clos des Barraults Rouge ($53)

Domaine Michel Juillot, 2020 Mercurey Premier Cru Clos des Barraults Rouge ($53)

Michel Juillot has the largest holding in Clos des Barraults and produces the most well-known Pinot Noir bottling from the site. The wine spends 18 months in oak barrels specifically built for Juillot, 30% of them new, which allows a soft wood undertone to follow the palate through raspberry jelly, spicy Morello cherry and a pleasant leatheriness that arises from the integrated tannins.

Domaine Michel Juillot, 2020 Mercurey Premier Cru Clos des Barraults Blanc ($53)

Domaine Michel Juillot, 2020 Mercurey Premier Cru Clos des Barraults Blanc ($53)

Clos des Barraults is a 12-acre climat, one of several Premier Crus lining the south-facing hill above the village of Mercurey. Barraults terroir is a classic Burgundian blend of clay, limestone and marl with a high proportion of lightly-colored gravel and pebbles. The southern exposure ensures good ripening with prolonged exposure to the softer morning sun. The wine is 100% Chardonnay and similarly soft, with vanilla-crème behind tropical fruit and bright, plucky acidity.

Gouffier

Frédéric Gueugneau may be seen as an archetype in the new blood that has infused Mercurey over the past decade. As a young man in the village of Fontaines (which sits between Mercurey and Rully) he was a laborer in the vineyards of Gouffier, which consisted of thirteen acres spread across eight appellations. Then under the direction of Jérôme Gouffier, the estate had been in the same family for two centuries.

Frédéric Gueugneau, Gouffier

In 2011, upon the death of Gouffier, Gueugneau was asked by his neighbors to take over the day-to-day management of the estate, bringing with him the eight years of experience he’d gained at La Chabliesienne, a wine cooperative in Chablis. He began by reinvigorating the farming philosophy, introducing organic practices; along with his partner Benoît Pagot, Gueugneau brought fresh thinking to the vines and to Gouffier itself—a picturesque estate that finds focus in a stunning, stone-domed cellar that once served as a bunker in the time of Napoleon.

Another unique feature of Gouffier is its close alliance with a single cooper. Doreau Tonneliers of Cognac is instrumental in finding the perfect match between barrel and wine, and in fact, nearly 20% of the wood used to make the barrels used by Gueugneau and Pagot comes from the forest just beyond the property’s walls.

Gouffier, 2020 Mercurey Premier Cru Clos l’Evêque Rouge ($49)

Gouffier, 2020 Mercurey Premier Cru Clos l’Evêque Rouge ($49)

In English, Évêque means Bishop and this Premier Cru climat once belonged to the Bishopric of Chalon-sur-Saône. The site is situated in the Mercurey fault-line at an elevation reaching one thousand feet. The wine is elegant, tinged with notes of cherry pit and forest floor underscored by wild bramble berries and finishing lean, dry and chalky.

Gouffier, 2020 Mercurey Les Murgers ($41)

Gouffier, 2020 Mercurey Les Murgers ($41)

‘Murgers’ refers to the stones that were removed from the plot to enable vine planting; Gouffier’s three-acre, east-facing plot is rich in loamy topsoil with deeper layers of clay that relies on deeper rocks to supply adequate drainage. Vines are pruned according to the Guyot Poussard method, which takes sap flow into account and reduces the damage that pruning may cause. The wine’s forward bouquet of cherries and raspberries are touched with sweet soil tones and subtle hints of smoke girded by silky tannins and integrated acidity.

Château de Chamirey

In 1934, the Marquis de Jouennes began to bottle the wines of Château de Chamirey at the domain; when his son-in-law Bertrand Devillard took over, he expanded the holdings to the present size and today, Amaury and Aurore Devillard stand proudly as the fifth generation of the family to manage the estate.

Enrico Peyron, Winemaker at Château de Chamirey

Of the 95 acres that encompass de Chamirey’s vineyards, about 70 are dedicated to Pinot Noir and the rest to Chardonnay; of the total, 21 acres are Premier Cru and about eight represent the acres for which de Chamirey is best known, Monopole wines, including those of Clos du Roi and La Mission. The peculiarly Burgundian term ‘Monopole’ dates back to Napoleonic inheritance laws that saw properties so subdivided (even down to individual rows of vines) that a lone grower was often not able to provide commercial grape quantities to négociants. A ‘Monopole’ wine represents a single area, often a lieu-dit vineyard, controlled by a single winery.

Château de Chamirey, 2020 Mercurey Premier Cru Clos du Roi Rouge ($52)

Château de Chamirey, 2020 Mercurey Premier Cru Clos du Roi Rouge ($52)

To elicit the maximum extraction of color and phenolics, the Pinot Noir is held pre-fermentation between 4 and 6 days, following which a full two week maceration concentrates tannins and aromatics. Clos du Roi is a southwest-facing, concave slope divided into 4 adjacent plots for a total of 7.6 acres planted between 1970 and 2002. The nose shows expressive strawberry and raspberry notes behind pie spices (cinnamon and nutmeg); the palate is cherries, plums, cassis, licorice and candied citrus peel.

Château de Chamirey, 2020 Mercurey Premier Cru La Mission ‘Monopole’ Blanc ($54)

Château de Chamirey, 2020 Mercurey Premier Cru La Mission ‘Monopole’ Blanc ($54)

La Mission is composed of three small plots totaling 4.75 acres and owned at 100% by Château de Chamirey; vines were planted between 1961 and 1997. Fermentation and aging take place in traditional Burgundian 228-liter barrels (15% of new) from the Allier and Vosges forests. The wine spends three months in tanks and goes through a light filtration before bottling; it shows a rich, rounded, golden character and carries the oak influence well.

Domaine Adélie

Domaine Adélie, comprising 20 acres of various Mercurey lieu-dits (including the Premier Cru, Champ Martin), was named for the daughter of Albéric Bichot, lead négociant at the famous Hospices de Beaune and owner of five other prestigious estates in Burgundy. He was voted best winemaker by the International Wine Challenge in three of the past ten years.

Albéric Bichot, Domaine Adélie

“Respect for the terroir and for nature is essential for us,” says Bichot. “We practice sustainable and organic viticulture. Starting with the 2018 vintage, the wines of Domaine Adélie will bear the certified ‘organic wine’ label.”

With this recognition comes a commitment to sustainable agriculture and a reverence for the uniqueness of each parcel and its stewardship. Despite the accolades, Albéric downplays the grandeur of his hallowed vineyards, preferring to talk about wine as a beverage to be enjoyed with friends, not over-analyzed or intellectualized.

Domaine Adélie, 2020 Mercurey ‘en Pierre Milley’ Rouge ($58)

Domaine Adélie, 2020 Mercurey ‘en Pierre Milley’ Rouge ($58)

From a 5-acre lieu-dit where the vine age averages 35 years old, the soil is rich in clay above bedrock that consists of compacted limestone with a few areas that are predominantly marl. The nose shows forward fruit with notes of wild berries, plum and peach while the velvety and smooth with a long, nicely balanced finish.

Domaine Adélie, 2020 Mercurey ‘Les Champs Michaux’ Blanc ($58)

Domaine Adélie, 2020 Mercurey ‘Les Champs Michaux’ Blanc ($58)

The lieu-dit ‘Les Champs Michaux’ is a three-acre site planted on calcareous clay where the Chardonnay vines, on average, are twenty years old. The wine is silken in the mouth with aromas of pears, green apples, peach and spring flowers. There is good depth and longevity with a persistent mineral finish.

NEW ARRIVAL

Burgundy’s Other White Grape

Aligoté Makes Its Case in Mercuery

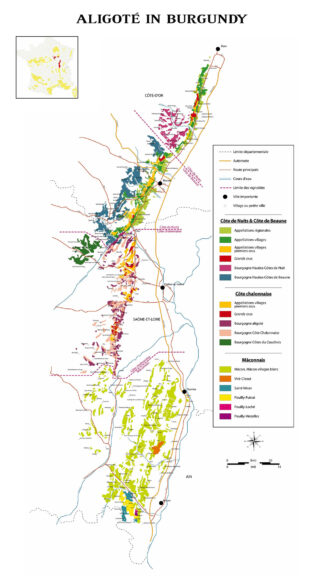

“Aligoté!” sounds like a cry of triumph; something you’d shout after making a goal in the World Cup. In fact, perennially overshadowed by its sexier cousin Chardonnay and even its half-sister Pinot Gris (they share a father, Pinot Noir), there was a time when the opposite was true:

“Before phylloxera,” says Jérôme Castagnier, proprietor of Domaine Castagnier in Morey-Saint-Denis, “Aligoté was planted everywhere, literally. But after the outbreak abated, thanks primarily to American root stock, French growers took stock and realized that Chardonnay and Pinot Noir commanded higher market prices, so that’s what was re-planted. In fact, in some regions, Aligoté was banned altogether.”

Post-phylloxera Aligoté exists under the basic Bourgogne Aligoté appellation established in 1937 and, for the most part, produces inexpensive and simple wines, especially when planted in the less-valued soils of the Saône Valley flatlands. But true Aligoté fans, including Les Aligoteurs (a group of French producers and wine lovers who promote Burgundy’s all-but-forgotten white grape variety) believe that the grape better expresses the terroir of thinner, rockier, hillside soils. A cross between Pinot Noir and the ancient white varietal Gouais Blanc, Aligoté’s profile includes descriptors ranging from fruit-driven and floral to herbal and sharp with acidity. In either case, it is the essential base for the classic cocktail Kir when blended with Cassis.

The grape is on full display in Bouzeron in the Côte Chalonnaise, which is a region that draws more interest from America than it does in its native France. Pockets of Aligoté exist throughout Burgundy, often on the fringes of the priciest real estate. It often presents itself as an ‘every day’ wine, and let’s raise a toast to that, since we have more ‘every’ days than we do special occasions. “Aligoté!”

Domaine Adélie, 2020 ‘Champ Renard’ Bourgogne-Aligoté Blanc ($28)

Domaine Adélie, 2020 ‘Champ Renard’ Bourgogne-Aligoté Blanc ($28)

100% Aligoté grown in the Champ Renard” lieu-dit located at the entrance of the village of Mercurey; the vineyard is worked with the same organic spirit and vinified using the same, traditional methods as the Chardonnay. The wine is dry and perfumed, showing notes peach, citrus and acacia flowers.

- - -

Posted on 2023.05.15 in Mercurey, Saturday Sips Wines, France, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

Burgundy With A Southern Accent: Four Producers Elevate Underestimated Côte Chalonnaise’s Givry to New Qualitative Heights

Join us for Saturday Sips

It is a pleasure to announce that we intend to make ‘Saturday Sips’ a permanent fixture of our Saturdays for the foreseeable future. Come at any time during our regular business hours and sample a few of the wines that we feature in our weekly newsletter. Along with the sips, our staff, along with myself, will be on hand to discuss the nuances of terroirs and the appellations that produced the wines we will taste.

Burgundy attracts as many investors as it does wine lovers; it’s no secret that the hallowed hills of eastern France produce some of the most sophisticated, terroir-influenced wines in the world—a product known for longevity, sensual appeal, and as a somewhat unpleasant side-effect, astronomical prices.

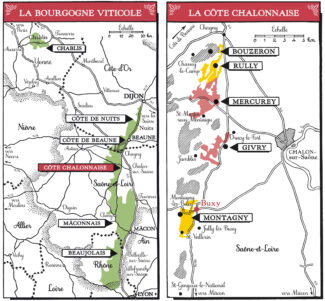

But by sheer volume, Burgundy is far less about shelf-dressers like Domaine Leroy’s Musigny and DRC’s Romanée-Conti Grand Crus, and more about the rustic wines of the countryside. These wines represent superb value in both Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, especially in villages like Mercurey, Montagny, Rully and Givry.

Givry is among these lesser-known names that we’ll be exploring this week; sensational examples of an appellation that produces extremely good wines that often fly beneath Sotheby’s radar, although they would be still be excellent wines at any price point.

Heading South to Côte Chalonnaise: Another Side of Burgundy

The legend of Snow White and Rose Red may have originated with the Brothers Grimm in Germany, but a modern reenactment can be found in the vineyards of Côte Chalonnaise. In this tale, the star performers are Pinot Noir as Rose Red and as Snow White, Chardonnay. Aligoté is an understudy, except in Bouzeron—the only appellation Village that is entirely produced from this ancient variety.

Sandwiched between the Côte de Beaune and the rolling hills of the Mâconnais, the Côte Chalonnaise is 16 miles long by four miles wide; the finest vines are planted on southeast slopes and produce red, rosé and white wines from 44 communes within cantons of Buxy, Chagny, Givry and Mont-Saint-Vincent. Like Beaune to the north, the soils of northern Côte Chalonnaise are limestone-dominated with outcrops of lias and trias formations. In the south, the limestone is marly, with sand and flint clays at the foot of the slopes. When graced with long, dry summers, Pinot Noir ripens beautifully, producing wines that (like Rose Red) are sassy, lively and cheerful while Chardonnay, sending roots deep into Burgundy’s clay, is more like Snow White: a homebody, redolent of gentle flowers with a suggestion of warm bread and honey. But in fairness to literary and vinicultural history, Côte Chalonnaise was already staging these heroines half a millennia before the Brothers Grimm penned their first ‘Once upon a time.’

Givry: Burgundy’s New Promised Land

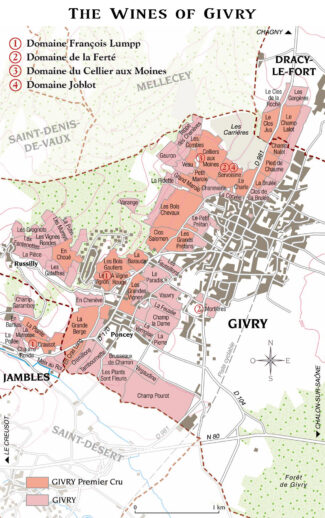

Located near the center of the Côte Chalonnaise, ‘Givry’ as an appellation covers not only Givry itself, but also the communes of Dracy-le-Fort and Jambles. The best vineyards sit on the south-facing, limestone-rich slopes immediately west of Givry itself. It is small, but top-heavy with Premier Cru vineyards, with 30 properties thus designated.

80% of these top sites are planted to Pinot Noir; only 24 acres grow Premier Cru white. Most of the Premier Cru vineyards boast terroirs based in brown soils derived from the breakdown of Oxfordian Jurassic limestone and clay where vines are planted facing east-south-east or due south at altitudes between 800 and 900 feet. As a result, the red wines of Givry tend to be fresh and expressive, showing strawberry and raspberry jam, fresh berries and delicate wisps of spice framed by supple tannins and refreshing acidity.

Critics have referred to these marvelous little villages in southern Burgundy as a ‘promised land.’ Our promise is that each of these wines over-produce for their price point.

2015 – Broad-Beamed with Aging Potential

The 2015 vintage was an extraordinary one throughout the Côte d’Or and Côte Chalonnaise. The red wines are truly great: rich, powerful and statuesque but almost always underpinned by juicy acidity. The distinctive characters of the region’s diverse terroirs, which can be occluded by over-ripeness in warm years, are articulately expressed. Nor, despite its richness and amplitude, is this a facile vintage. These are wines built for the long haul, with serious reserves of ripe tannins hidden behind their generous fruit: they deserve patience, and—if they briefly shut down in bottle—they demand it.

Although some vignerons have drawn comparisons between Vintage 2015 and the excellent Vintage 2005, yields were lower in 2015 and the wines are more concentrated. Others look to 1990 for an analogy. Perhaps the last word should go to Volnay’s Michel Lafarge, one of the Côte d’Or’s most thoughtful and experienced observers, who draws parallels with 1929s which he tasted as a young man in his family’s cellars, “No other vintage in the past 60 years is really comparable.”

2015 began as an ideal growing season, then excessive July heat began to pose some problems, which were eased by intermittent rains in August. Results were excellent overall with lush, ripe, broad-beamed wines produced in most Premier Cru sites.

François, Son Pierre, Daughter Anne-Cécile, and Isabelle Lumpp, Domaine François Lumpp

Lumpp and his brother inherited their family property in 1977; in 1991 François founded his own label with his wife Isabelle and planted cuttings of older, selected bud wood (Sélection Massale) in Givry’s best Premier Cru sites, situated on the mid to upper level slopes of the hills. At harvest, pickers sort the grapes carefully at each vine, and then they are checked again on the sorting table. François aims to pick at optimum ripeness, favoring the bright acidic profiles of wines which have developed on the vine rather than masked by their time in barrel.

Domaine François Lumpp, 2015 Givry Premier Cru A Vigne Rouge ($63)

Domaine François Lumpp, 2015 Givry Premier Cru A Vigne Rouge ($63)

A full-bore representation of Lumpp’s finesse, a wine from his 6-acre Premier Cru site ‘A Vigne Rouge’ that manages to be both notably ripe yet elegantly cool with an airy combination of earth, red currant and discreet spice nuances. A beautifully refined mouth leading to a lingering and complex finale.

Domaine François Lumpp, 2015 Givry Premier Cru Crausot ($72)

Domaine François Lumpp, 2015 Givry Premier Cru Crausot ($72)

Perhaps Givry’s best terroir for Chardonnay and one of François Lumpp’s highest-elevation parcels, the Climat ‘Crausot’, with a 2.5-acre holding, also produces elegant, ample Pinot Noir with juicy red berry up front, licorice and pie spice in the background.

2020 – Dramatic, Concentrated with Surprising Levels of Freshness

François Labet, a négociant whose family has lived in Beaune for 300 years, summarizes the 2020 vintage like this: “An intellectually-challenging vintage; the reds in particular defy easy categorization because the impact of that season varied considerably by terroir. Producers had key decisions to make, especially when to pick and that significantly affected both the style and quality of the resulting wines.

And this is because the most notable feature of this vintage was its early and rapid harvest: Many domains began picking the week of August 17th and while August harvests have been frequent in the 21st century (there were none in the prior century), this was for many domains the first time they had not only started, but completed a harvest before the end of August.

The resulting wines (particularly from earlier harvests where sugars were high and acids intact) are remarkable, both for whites and reds. The season was hot and dry, but water tables were healthy from the mild and wet preceding winter.

Beaune and Côte Chalonnaise were particularly fortunate and Chef de Cave Frédéric Weber (Bouchard Père et Fils) describes 2020 as a concentrated and strong vintage: “It reminds me of 2016 for its vibrancy and energy; the wines are voluptuous and structured. A great vintage for the future, like the ‘18s.”

Domaine de la Ferté

Domaine de la Ferté is one of five estates owned by the Devillard family (which also includes Château de Chamirey and Domaine des Perdrix); Ferté covers a relatively small area of six acres spread over three plots, two in the village appellation of Clos Mortière and one in Servoisine Premier Cru. It thrives under the direction of oenologist and ‘chef de culture’ Enrico Peyron.

Enrico Peyron, Winemaker at Domaine de la Ferté

Peyron says, “We are privileged to grow in some of most renowned Premier Crus of the appellation; we plant with 4000 vines per acre, a high-density that is Burgundian tradition that ensures high quality wine. The grapes are harvested with great care and experience and limited use of treatment products, while the average age of our vines is 35 years.”

Domaine de la Ferté, 2020 Givry ($43)

Domaine de la Ferté, 2020 Givry ($43)

A Village-level wine from Pinot Noir vines planted in 1985; the vineyard is surrounded by two Premier Crus and features south-east exposures in deep clay soils. The wine is aged 9 months in 228-liter Burgundian barrels of which 20% are new and shows fresh notes of wild strawberries and supple pie cherries behind a bit of cola and mineral crispness.

Domaine de la Ferté, 2020 Givry Premier Cru Clos de la Servoisine ($49)

Domaine de la Ferté, 2020 Givry Premier Cru Clos de la Servoisine ($49)

Servoisine is a south-facing Climat planted sixty years ago; the wine displays luscious notes of sweet cherries, cassis, licorice and loamy soil. This is a marvelous, full-bodied and concentrated wine with powdery tannins and lively acidity.

Domaine du Cellier aux Moines

Overlooking one of Givry’s historic Premier Crus, the Cellier aux Moines was magnificently restored by Catherine and Philippe Pascal and their three children. Pascal is the former CEO of Veuve Clicquot and the Moët Hennessey Group, and after retiring from the company, he began a search throughout Burgundy for a restoration project, ultimately settling on an overgrown vineyard slopes of Givry’s ancient monastery, La Ferté Abbey, which had produced wine in the region going back nine centuries.

“The vineyards and the monastic cellar were in terribly bad shape,” says Pascal, “but we realized that this ancient estate presented a unique opportunity to rediscover a star appellation for Pinot Noir. Despite Givry’s reputation as a bit player in the Burgundy wine scene, I must insist that the area has been unfairly underrated.”

Philippe Pascal and Viticulturist / Winemaker Guillaume Marko, Domaine du Cellier aux Moines

In 2015, Guillaume Marko joined the Domaine as head of vineyards and winemaking operations. Holding a DNO (Diplôme National d’Œnologie) from Dijon University, Guillaume trained during few years in famous wine estates of Côte de Nuits, including Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. Marko maintains: “The challenges have been many—reclaiming the steep, bush-covered hillsides, mapping soils, converting to biodynamic winemaking and constructing an entirely new gravity-fed winery—but the results have been remarkable: In my opinion, and that of many critics, Domaine du Cellier aux Moines now produces some of the most coveted wines in Givry.”

Domaine du Cellier aux Moines, 2020 Givry Premier Cru Clos du Cellier ($87)

Domaine du Cellier aux Moines, 2020 Givry Premier Cru Clos du Cellier ($87)

One of Givry’s historic Premier Crus, Clos du Cellier is twelve acres replanted with superior selections of Pinot Noir. The intensity of the wine’s garnet color is matched by the complexity of the aromas, evoking violets, tart cherry conserve and damp forest floor. There is vibrant tension between texture and acidity and a long aftertaste with dusty tannins and notes candied Morello cherry.

Domaine du Cellier aux Moines, 2020 Givry Premier Cru Clos du Cellier ‘Les Dessus’ ($176)

Domaine du Cellier aux Moines, 2020 Givry Premier Cru Clos du Cellier ‘Les Dessus’ ($176)

From the upper slopes of the vineyard, where the soils are characterized by harder, less decomposed limestone, this wine saw a full 23 months of élevage before bottling. Mingling scents of red berries and plums with notions of peony, rose and bergamot introduce a medium to full-bodied wine with a bright core of fruit and a beautifully perfumed finish.

Domaine du Cellier aux Moines, 2020 Givry Clos Pascal ‘Monopole’ Rouge ($288)

Domaine du Cellier aux Moines, 2020 Givry Clos Pascal ‘Monopole’ Rouge ($288)

Just above the Clos du Cellier is another tiny plot (two-thirds of an acre) surrounded by thick walls which had been left fallow since the phylloxera crisis. Replanted in 2010, it was named ‘Clos Pascal.’ The wine shows nicely lifted raspberry tones with ripe cherry beneath, along with a touch of sandalwood and refined tannins.

Reaching Peak: Two Decades in The Making

2003 Givry Premier Cru: Domaine Joblot ‘Clos de la Servoisine’

Juliette Joblot is the fourth generation in the Joblot clan to farm the family domain in Givry’s unique amphitheater. The estate was founded by Charles Joblot after the First World War, although it not until the 1960s that Marc (Charles’s son) began to bottle the wine under the Joblot imprint. Marc passed the property to his sons Jean-Marc and Vincent in the 1970s, who truly forged the estate’s reputation. When Juliette, took over she brought the ecological revolution to the vineyard and tweaked the house style: Unlike the many growers in the area who determine the ripeness of their grapes based on sugar levels, Juliette bases her picking decisions on acidity levels. During the harvest, severe sorting takes place in the vineyards, and Juliette is known to drop up to 40% of a vintage if it does not meet her standards.

Juliette Joblot, Domaine Joblot

In the cellar, 90% of the Pinot Noir is de-stemmed, and long, cool macerations are encouraged. The Chardonnay from the ‘En Vau’ lieu-dit vineyard as well as the fruit that contributes to the cuvée ‘Mademoiselle’ is pressed slowly to preserve freshness and to avoid off-flavors that may result from aggressive handling. Each parcel is vinified separately and each cuvée undergoes natural fermentation in an identical manner so that the character of the individual terroirs come through.

Although the wines drink well on release, they have a track record for aging 20-25 years in good vintages, meaning that the following wine is an ideal cross-section of what a mature Joblot red represents.

Domaine Joblot, 2003 Givry Premier Cru Clos de la Servoisine ($98)

Domaine Joblot, 2003 Givry Premier Cru Clos de la Servoisine ($98)

Twenty years into it, the excellent 2003 vintage has grown up. In its youth, Servoisine red wines from 2003 displayed plenty of energy, refreshing acidity, plumpish body and a good quality of ripe and silky tannin. Today, these sunny wines are no less lovely and are certainly more complex; as the fruit recedes, the bones of earth begin to poke through, although the purity and precision remains. The acidity is more apparent and the style is both mellow and brisk with a touch of austerity manifested as cool minerality and edge.

Bottle Size Matters: When Aging Wine, The Bigger, The Better

When making a wine purchase for immediate serving, the primary information you’re after may be the number of glasses in a given bottle. For a standard bottle, you’ll get about five five-ounce glasses of wine, while a magnum—1.5L or 50 ounces will fill 10 glasses. Logically, a half-bottle equals 2.5 five-ounce pours. But there is more to consider when you buy a wine that you intend to leave in bottle to mature, since format has an effect on a wine’s ability to age. This is the result of oxygen exchange relative to the amount of wine in the bottle. A magnum has about the same ullage (the space between the top of the liquid and the bottom of the cork) as a standard 750ml bottle. However, it has twice the volume of wine, so the ratio of wine to oxygen is significantly impacted and, by extension, so is the aging potential of the wine and the speed at which it occurs.

The following wines from this week’s selection are also available in magnums.

2020 Domaine du Cellier aux Moines, Givry Premier Cru Clos du Cellier ‘Les Dessus’ ($360) 1.5 Liter

2020 Domaine du Cellier aux Moines, Givry Clos Pascal ‘Monopole’ ($600) 1.5 Liter

2017 Domaine du Cellier aux Moines, Givry Clos Pascal ‘Monopole’ ($450) 1.5 Liter

2019 Domaine de la Ferté, Givry Premier Cru Clos de la Servoisine ($140) 1.5 Liter

- - -

Posted on 2023.05.06 in Givry, France, Saturday Sips Wines, Burgundy | Read more...

Lure of The Loire: A Range of Red Grapes, Soils and Microclimates Allow for A Diversity of Wines and Styles by an Upstart Generation 12-Bottle Sampler $369

The media engine behind French wine seems driven primarily by two wheels—Burgundy and Bordeaux—while the Loire is often relegated to third-wheel status. And it’s not from want of praise: The vivid, crisp, hauntingly aromatic and almost supernaturally focused wines of the Loire Valley are arguably the pinnacle of each particular varietal.

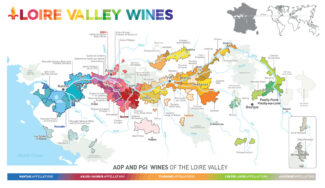

And there are many. 24 varieties flourish throughout the Valley (including indigenous, newly-revived grapes such as Pineau d’Aunis) alongside the Big Four, Melon de Bourgogne, Sauvignon Blanc, Chenin, and Cabernet Franc. The Loire Valley is the biggest producer of white wine in France and the second biggest producer of sparkling wines; it encompasses four sub-regions with more than 51 appellations surrounding the Loire River and its tributaries, flowing from the east around Sancerre to the west toward Muscadet on the Atlantic coast at the mouth of the river.

The Loire is also a hot-bed for experimental winemakers, some of whom have chosen to forgo the hidebound restrictions of the French wine bureaucracy and produce wines on their own terms, opting to use the all-encompassing Vin de France appellation on their labels rather than the prestigious AOPs they’d otherwise be entitled to. Lovers of natural wine know that the Loire was an early pioneer in the movement, and that such producers make wine with organic and/or biodynamic fruit, native yeasts, and a commitment to low-intervention viniculture as a bid for sustainability in the face of changing environment.

These upstart young winemakers have not only been flying under the mainstream radar, they have created their own generation of satellites—fans that recognize wine as an agricultural product as well as a cultural phenomenon, and are drawn to their dedication to natural farming.

This week’s wine package looks upward toward the light that vignerons in two specific Loire appellations—Anjou-Saumur and Touraine—are shining on technique, innovation and originality.

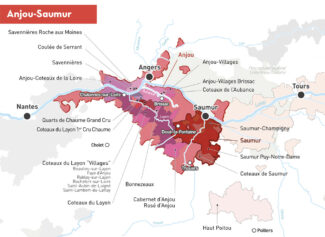

Anjou-Saumur: Driving a Full-on Revolution

In France, where plenty of revolutionaries wound up with their heads in a guillotine basket, ‘revolution’ is not a word to be used lightly. Still, Richard Leroy of Domaine Sophie et Richard Leroy in Bellevigne-en-Layon, Anjou, uses it easily: “There’s a revolution happening in wine right now,” he says, referring to Anjou, once an epicenter for sweet wines like Coteaux du Layon and Quarts de Chaume.

Over the past twenty years, Anjou has become a hub for a different kind of wine—those made with a minimum of artifice in the cellar, free from historical baggage about what they should taste like and often produced by first-generation winemakers with no family ties to wine.

Another phase of the revolution is the revival of Chenin, which fell out of favor during the second half of the last century as did the native red wine grape, Grolleau. Mark Angeli of La Ferme de la Sansonnière,who arrived in 1989, claims, “Dry Chenin had been gone from Anjou for 50 years, and the few reds being made were mostly rot-gut. Appellation rules required them to be made from the two Cabernets—Franc and Sauvignon—even though old-vine parcels of Grolleau and Pineau d’Aunis thrived throughout the area.”

The region has been attracting maverick winemakers who recognize the scant precedent for complex, dry wines made from Chenin Blanc and Grolleau, and who have been happy to bottle their rule-busting wines, farmed organically, under the relatively lowly ‘Anjou’ appellation or even labeled simply as ‘Vin de France.’

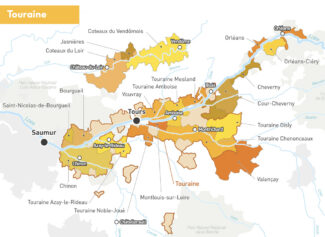

Touraine: The Original Breeding Ground of Natural Wines & Pioneering Winemakers

Most people are more familiar with the Loire’s bookends, Muscadet and Sancerre. But between them lie 79 AOPs representing what InterLoire (the official organization of producers, merchants and traders involved in the production and promotion of Loire wines) calls, “The most extensive, diversified and original vineyards in Europe.”

The AOP covering Touraine stretches from Anjou to the west to the Sologne in the east, converging near the point where the Loire River and its tributaries meet. It covers 104 communes in Indre-et-Loire and 42 in Loir-et-Cher.

Most of the vineyards are located southeast of Tours on the slopes that dominate the Cher River and the land between the Cher and the Loire. With nearly 13,000 acres under vine, the climate varies dramatically as you move inland; oceanic conditions dominate the west, becoming more continental as you move east. These climatic differences combined with varied soils determine the choice of grape variety planted (with later-ripening varieties grown in the west and earlier-ripening ones in the east) and account for the wide variety of wine styles produced.

Among these styles are the personal statement’ wines of natural winemakers, who have found in Touraine a vibrant opportunity for self-expression as well as terroir that, through minimal intervention, display their origins perhaps even more faithfully than their rule-bound AOP counterparts.

Cabernet Franc

Who’s your daddy? Biologically, both Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot share Cabernet Franc as a parent, and the grape itself displays characteristics inherited by both. In cooler climates, Cabernet Franc shows off graphite and red licorice notes, while in warm regions, it exhibits tobacco and leather aromas. There is also a vegetal edge, which may strike the palate as tasting of green pepper or jalapeño.

In Bordeaux, it is generally a minor component of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot blends, although in Pomerol and Saint-Émilion it adopts a larger, more highly-regarded role. Cheval Blanc, for example, is typically around two-thirds Cabernet Franc while Ausone is an even split between Cabernet Franc and Merlot.

With the Loire Valley’s cool, inland climates it becomes a star performer. The appellations of Chinon (in Touraine) along with Saumur and Saumur-Champigny (in Anjou) are important bastions of Cabernet Franc, where the wine is prized for forward aromas of ripe summer berries and sweet spices.

The local Loire Valley name for Cabernet Franc is Breton; a reference to the man credited with bringing the variety to popularity in the 17th Century.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge (Anjou-Saumur)

Intense, driven and passionate, Guillaume Reynouard is the fox in charge of the chicken coop—as well as being a winemaker, he is president of the Syndicat des Vins Saumur and has a particular enmity for growers who rip out Pineau d’Aunis in favor of easier-to-grow varieties.

Taking charge of Domaine Manoir de la Tête Rouge in 1995, Guillaume soon converted to organics and was certified Biodynamic in 2010. The estate enjoys remarkably productive clay/ limestone terroir and he takes pride in ‘living vineyards’ where the soil is worked by hand to ensure that roots go deep and grass grows between rows to promote insect and other plant life; synthetic chemicals are prohibited. In the cellar, grapes are fully destemmed, indigenous yeasts are preferred, with no additions and very minimal sulfur use.

Guillaume Reynouard, Manoir de la Tête Rouge

According to Reynouard, “Responsible agriculture is a way of life and of thinking. When growing grapes, I aspire to act sensibly for the planet—a state of mind that develops naturally from a respectful relationship with nature. Knowing how to adapt to a changing environment requires constant questioning while the planting of forgotten varieties such as Pineau d’Aunis, the incorporation of trees into the cultivation of the vine (agroforestry) and the gradual abandonment of ‘modern’ oenology are avenues that I have followed for more than 20 years.”

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘l’Enchentoir’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ‘natural’ ($43)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘l’Enchentoir’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ‘natural’ ($43)

In the sub-appellation Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame, ‘l’Enchentoir’ is a venerable Cabernet Franc lieu-dit. Planted over Turonian limestone in 1959 using sélections massales, the pressed wine is aged in 300-liter barriques for one year plus another six months in Béton cuves (pre-cast concrete tanks). It displays depth and delicacy, showing blackberry and cherry over violets, rose petals and savory herbs.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Tête de Lard’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ($27)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Tête de Lard’, 2018 Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame ($27)

100% Cabernet Franc from two parcels averaging 20 years of age, ‘Tête de Lard’—Head of Bacon’—is fermented on native yeasts and spends a year in used 300-liter barrels. The final blend is done in concrete tanks, where the wine rests for 4 months before bottling. Filled with ripe tones of blueberry and cassis with a slight vegetal edge, this is a natural wine suited for the cellar, but one that should be tasted every couple years to keep an eye on the progress.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Bagatelle’, 2020 Saumur Rouge ($21)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘Bagatelle’, 2020 Saumur Rouge ($21)

A bagatelle is something easy; something that requires little effort. This is not a comment on the precision that is de rigeur in Guillaume Reynouard’s winemaking, especially since the tech sheet for this wine specifies the terroir as 30% Jurassic limestone, 60% Turonian limestone and 10% silt, and the vines as being pruned in alternating Guyot-Poussard. Rather, the wine itself is created simply and naturally, macerated three weeks without yeasting, without chaptalization and without additives, then matured without sulfur. These minuses equal an ultimate plus; a pure Cabernet Franc with aromas of plum, raspberry, and cherry with notes of red pepper, spice, and graphite with silky tannins and bright acidity.

Le Sot de l’Ange (Touraine)

Although the label’s name roughly translates to ‘Idiot Angel’, winemaker Quentin Bourse is anything but. Before taking over a friend’s estate in time for the 2013 vintage, Bourse worked in various fields (some wine related; others not) including numerous internships in the surrounding area. Having learned technique from both natural and conventional producers, notably a six-month stage at the famed Vouvray producer Domaine Huet, his winemaking philosophy was shaped by philosophy and a relentless work ethic that leans toward innovation and the sort of perfectionism that is often at the root of natural wines—at least the ones that shine.

Unusual for the neighborhood, Bourse’s estate is certified biodynamic. Ranging across 30 acres, he is especially attracted to indigenous varieties that capitalize on the clay and silica soils for which the region is famous. In many of his parcels, white silex stones litter the rows making it look as if the terroir is seeping from the earth.

Quentin Bourse, Le Sot de l’Ange

He shares a cellar with old-school producer Pascal Pibaleau, where his grapes are painstakingly sorted four times before whole-cluster fermentation with indigenous yeasts in tank, and then a slow, gentle pressing that in some cases lasts five or more hours. Aging occurs either entirely in tank, neutral barriques, or amphorae depending on the cuvée, and zero sulfur is added during the winemaking process for the reds; a touch is added for the whites.

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Karadras’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine Cabernet Franc ‘natural’ ($24)

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Karadras’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine Cabernet Franc ‘natural’ ($24)

‘Karadras’ is 88% Cabernet Franc and 12% Côt; the name proves to be somewhat inexplicable since it appears in different spellings on different bottlings. What remains the same is that after being manually destemmed in wicker baskets, the fruit ferments in open wooden tanks and comes out the other end with a classic profile; a bit of color from the Côt, herbaceous notes from the Cab Franc. It offers dusty plum, soil, cocoa, and brambles; the palate is lively and fresh, lifted by crunchy acidity framing the ripe high-toned blue fruits, juicy plum and earthy spices.

Côt

‘Côt by any other name would smell like Malbec.’ With apologies to the Bard, the renaissance of this dark, potent grape in the Loire sees a remarkable change in profile. In southwest France—Cahors in particular—the variety produces heavy wines that are not only amenable to long periods of aging, they virtually demand it. In the Cher Valley, in the heart of Touraine, the grape finds a kinder, gentler environment where it produces a different sort of wine; less aggressively tannic with fresh aromas of black cherry and cassis. In part, it is the climate, but the fiercer aspects Côt as they appear in Cahors’ ‘black wines’ are tempered in the field, where vines are pruned short with a vendange vert after véraison. To avoid the additional tannins of oak, most of the grapes are fermented and aged in stainless steel tanks with a few barriques blended in.

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Le Jardin’, 2018 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘Côte’ ‘natural’ ($45)

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘Le Jardin’, 2018 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘Côte’ ‘natural’ ($45)

100% Côt from an interesting lieu-dit with two distinct soil types—one section with clay and silex soils and the second with clay and limestone. The wine is vinified using whole-cluster fermentation in concrete tank; malolactic fermentation and élevage occur in terra cotta amphorae for 24 months. The wine shows aromas of freshly-picked bramble fruits, blackberry and currant, with slight Szechuan pepper notes and a touch of clove; a fresh, gripping palate.

Pineau d’Aunis

“Pineau d’Aunis is a regional grape found mostly around Anjou and Touraine in the Loire Valley,” says Arthur Hon, the U.S. spokesperson for Loire Valley Wines. “It can be used for still red, still rosé or sparkling rosé, though it’s more commonly blended and used for regional rosé.”

Named after the Prieure d’Aunis, a priory located halfway between Saumur and Champigny, d’Aunis is Loire’s birth child, and however well the adopted clan has done—Gamay, Cabernet Franc, Malbec—this grape may exemplify the terroirs of the Valley better than any. Still, it can be a problem child: Pineau d’Aunis is prone to producing irregular yields and with tightly packed bunches, it is highly susceptible to rot, including botrytis. It is also sensitive to the soil conditions it is grown in, requiring a balance of clay, sand and gravel as ideal conditions.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘K’ Sa Tête’, 2020 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ Guillaume Reynouard ($27)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘K’ Sa Tête’, 2020 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Pineau d’Aunis’ Guillaume Reynouard ($27)

100% Pineau d’Aunis from the lieu-dit de l’Enchentoir where soils are treated using Maria Thun’s biodynamic advice; this includes cow-horn dung in the spring and horn silica after closure of the cluster (a somewhat exacting process that is exactly what is sounds like, using cow-horns filled with manure and/or silica). Maceration lasts 12 days in concrete tanks without yeasting, chaptalization or additives. The wine spends six months in oak barrels and bottling is done in June with 20 mg of added sulfur. This is a textbook Pineau d’Aunis with black pepper, green pepper and jalapeño on the nose with a palate that expands to include sweet, perfectly ripe blueberries.

Grolleau

Grolleau is the Loire Valley’s workhorse grape, used most often in the production of rosé. Although it remains one of the Loire’s most planted red-wine varieties, new plantings have dropped steadily for the last 50 years. While Grolleau is high yielding, providing a steady, reliable harvest, it poses several challenges for growers as it is susceptible to disease and not a particularly flavorful stand-alone variety. It is a dark grape on the vine, but thin-skinned, meaning that there is not much chance for color extraction, so it is rarely used to produce red wines.

Grolleau-based wines tend to be high in acid, moderate in alcohol, and may show aromas of strawberry, raspberry and cherry; as a rosé, it is reminiscent of watermelon, tangerine, rose petals and red candy.

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘À Tue Tête’, 2021 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Grolleau Gris’ Guillaume Reynouard ‘natural’ ($25)

Manoir de la Tête Rouge ‘À Tue Tête’, 2021 VdF Loire-Saumur ‘Grolleau Gris’ Guillaume Reynouard ‘natural’ ($25)

Vin de France is the most basic quality tier for wines from France, typically uncomplicated everyday drinks, likely blends, but occasionally are made from unlisted, unqualified varieties. Loosely translated to ‘loudly’, ‘À Tue Tête’ is a rare bottling from an even more rare variety, Grolleau Gris, which is a pink-skinned mutation of Grolleau. Handled with the biodynamic tool-kit, the wine shows red cherry, sandalwood and a bit of tropical fruit.

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘OG Grolleau’, 2020 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘natural’ ($39)

Le Sot de l’Ange ‘OG Grolleau’, 2020 IGP Val-de-Loire ‘natural’ ($39)

IGP (Indication Géographique Protégée) is a quality category used for French wine positioned between Vin de France and Appellation d’Origine Protégée (AOP). (The category superseded Vin de Pays in 2009.) Most significant in commercial terms is the fact that the wines may be varietals and labeled as such. ‘OG Grolleau’ comes from single parcel of old-vine Grolleau planted between 1945 and 1976; grapes are de-stemmed, given ten days of maceration, aged in amphorae and used oak barrels, then bottled without sulfur. Blueberry and violet dominate the nose while the palate resolves itself in a mineral crunchiness with beautiful acidity.

Gamay

Ever since Philippe de Bourgogne cast Gamay from the bosom of Burgundy six centuries ago, the variety has been derided and even despised outside its spiritual home, Beaujolais. Folks who were soured by the sweet and fruity Nouveau cult may bring that prejudice into Touraine, but that would be a mistake: Although once in the shadow of Anjou Gamay, select vignerons in Touraine have made monster strides with Gamay over the past couple decades and these wines now edge out the Gamays of Anjou in depth and complexity. They tend to be medium-bodied with a musky tone that share center stage with aromas of fern and capers intermingled with flinty minerals and plummy notes.

Clos Roussely (Touraine)

Clos Roussely was once a lowly outbuilding of the great fortification at Angé-sur-Cher and as it happens, its five-foot-thick Tuffeau walls serve to insulate the winery as efficiently as they once held off Attila the Hun. Not only that, but the 250-year-old hand-dug caves beneath it are ideal for aging the remarkable wines of Vincent Roussely. The transition from barn to vignoble began in 1917, when Anatole Roussely became the first of four generations to dedicate his life to detail; Vincent Roussely, his great-grandson, today works this remarkable terroir—22 acres of clay and limestone peppered with pockets of silex.

“It was my childhood dream to work these soils,” says Roussely, who inherited the estate in 2001. “The terroir is ideal for Sauvignon Blanc, which makes up about 80% of our plantings, but at the heart of Roussely is a small plot of old-vine Gamay. We also have Côt (Malbec), Pineau d’Aunis and a little Cabernet Franc. We have always farmed organically, both for the health of the vines and out of social responsibility, but we were officially certified in 2007.”

Vincent Roussely, Clos Roussely

The old-school methodology runs through every aspect of the winemaking process. Grapes are hand-harvested and are subject to slow, natural fermentation in the cool catacombs; Gamay undergoes the familiar Méthode Beaujolais, partial carbonic maceration in which some whole grapes are kept intact and begin alcoholic fermentation within the confines of their skins.

Evolving from tradition to technology, Roussely continues to experiment, using concrete eggs for some of his fermentations. “Innovative adaptation means more than simply exploring new techniques,” he says. “It also involves a commitment to ecological responsibility. Right now, about 65% of Loire Valley vineyards are organic and it’s our goal to see that number at 100% by 2030.”

C los Roussely ‘Canaille’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘Gamay’ ($21)

los Roussely ‘Canaille’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘Gamay’ ($21)

‘Canaille’ is the French word for ‘scoundrel.’ 100% Gamay from vines between 25 and 50 years old grown organically on clay and limestone. Aged six months in stainless steel, the old vines add a striking depth to this exuberant Gamay, replete with notes of crushed raspberry, black cherry and nutmeg.

Domaine Marie Thibault (Touraine)

“I grew up in the Loire Valley, but unlike many vignerons working in the Loire, I did not come from a winemaking family,” says Marie Thibault, adding, “But also unlike many of them, I have degrees in both biology and oenology.”

Marie Thibault began making wine in the early 2000s, working for a time with François Chidaine in Montlouis, where she fell in love with Chenin. In 2011, she founded her own nine-acre estate on a single windy slope in Azay-le-Rideau, a lesser known commune of Touraine. She immediately converted to organics and has been certified with Ecocert since 2014. Among the natural elements in her vineyards is the flock of two dozen ewes that graze between the vine rows during the autumn; every ten days, they are penned inside a new hectare to keep the soil naturally fertile and the grass clipped.

Marie Thibault, Domaine Marie Thibault © Jean-Yves Bardin

“My vineyard is small, but the soils are extremely varied and as such, so are the grapes I grow. I work with Côt (Malbec), and have a special love for Gamay, Grolleau, Chenin and Sauvignon Blanc. Most of my vines are at least 50 years old. I compensate for small production by purchasing from organic estates nearby.”

Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Les Grandes Vignes’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘Gamay’ ‘natural’ ($41)

Domaine Marie Thibault ‘Les Grandes Vignes’, 2018 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘Gamay’ ‘natural’ ($41)

Thibault’s unique lens on Gamay is seen in this example produced from 50+ year-old vines she discovered growing adjacent to her plot on flinty silex soil. The vines were untrained and un-trellised, and harvest was exceptionally labor-intensive. She allows a 10-month maceration in order to shows off the Gamay’s savory side, with crisp rhubarb, earthy red berry notes and fine-grained, well-integrated tannins showcased.

Jérémy Quastana (Touraine)

Jérémy Quastana is a young vigneron who trained under Olivier Lemasson for a few years before snagging five acres of his own near Lemasson’s main plot in the Loir-et-Cher not far from Cheverny. Prior to that, Jeremy learned the trade at Marcel Lapierre’s Beaujolais winery and did a six-month internship at Clos Ouvert in Chile.

Jérémy Quastana, photo: Alberto Rodriguez

Quastana farms a single plot composed of young-vine Gamay, middle-aged Côt and old-vine Gamay planted on a gentle slope of clay over silex. Jeremy has not applied for AOP recognition, since—like many natural winemakers—he knows the challenge of following commission rules. His wines are unembellished—fresh, pure juice that may serve as a perfect aperitif on a warm day, but which always qualify as a serious approach to winemaking the natural way.

Syrah

Syrah, in France most often associated with the sultry climes of the Northern and Southern Rhône; Côte Rôtie means ‘roasted slope’ to give an indication of how hot this area gets. In Hermitage, the grape produces prestigious wines packed with sun-ripened fruit flavors and lots of potential for aging—these wines are deep, black, tannic and powerful wines.

In the Loire, it is not widely planted, but when vinified using the carbonic maceration technique of Beaujolais, it produces a similar sort of fruity, wonderful concoction that shows off a more delicate side.

Jérémy Quastana ‘Syrah’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘natural’ ($30)

Jérémy Quastana ‘Syrah’, 2021 VdF Loire-Touraine ‘natural’ ($30)

Some mystery surrounds the origin of these grapes since the Quastanas will purchase grapes on occasion. Wherever this Syrah originated, it is unique interpretation, filled with wild strawberries, white pepper and a pleasant grassiness behind sparks of acidity. Tannins are subdued, and this is an immediate wine that is best consumed young.

Notebook …

The Gesture of Being ‘Natural’: Wine in The ‘Raw’

In wine, ‘natural’ is a concept before it’s a style. It refers to a philosophy; an attitude. It may involve a regimen of rituals or it may be as simple as a gesture, but the goal, in nearly every case, is the purest expression of fruit that a winemaker, working within a given vineyard, can fashion. Not all natural wines are created equal, and some are clearly better than others, but of course, neither is every estate the same, nor every soil type, nor each individual vigneron’s ideology.

The theory is sound: To reveal the most honest nuances in a grape’s nature, especially when reared in a specific environment, the less intervention used, the better. If flaws arise in the final product—off-flavors, rogue, or ‘stuck’ fermentation (when nature takes its course), it may often be laid at the door of inexperience. Natural wine purists often claim that this technique is ancient and that making wine without preservatives is the historical precedent. That’s not entirely true, of course; using sulfites to kill bacteria or errant yeast strains dates to the 8th century BCE. What is fact, however, is that some ‘natural’ wines are wonderful and others are not, and that the most successful arise from an overall organoleptic perspective may be those better called ‘low-intervention’ wine, or ‘raw’ wine—terminology now adopted by many vignerons and sommeliers.

At its most dogmatic and (arguably) most OCD, natural wines come from vineyards not sprayed with pesticides or herbicides, where the grapes are picked by hand and fermented with native yeast; they are fined via gravity and use no additives to preserve or shore up flavor, including sugar and sulfites. Winemakers who prefer to eliminate the very real risk of contaminating an entire harvest may use small amounts of sulfites to preserve and stabilize (10 to 35 parts per million) and in natural wine circles, this is generally considered an acceptable amount, especially if the estate maintains a biodynamic approach to vineyard management.

In all things wine, ‘balance’ is a key to the kingdom; it is a term interchangeable with harmony, and may reference acid, alcohol level, grape sugars and tannin, but also, to a scale in which the long-term health of the product is considered along with the flavors inherent on release. More than just a current radar blip in trendy social capital a naturalistic approach to winemaking is not only more honest, but better for a sustainable environment: It’s a nod to the past and a gesture to the future.

VdF & IGP Designations: Forgoing Restrictions

Wines in France are classified into one of three categories: AOP (Appellation d’Origine Protegée, formerly AOC), IGP (formerly Vin de Pays) and Vin de France. AOP wines are identified only by the names of their appellations, usually without varietal descriptions; the next level, IGP, comes from broader regions, and may be identified by varietal names; and the lowest level has no indication of origin at all.

Vin de France is a catch-all. Produced often at high yields, most Vins de France are low-priced, but hidden within them are top wines, pushed out of the appellation system, that can be every bit as good as the best in the AOP. They can be hard to identify, because origins aren’t obvious – many indicate only the names of producer and cuvée – and while they may seem expensive for this lowly category, they can offer remarkable interest. With only a few high-flying Vins de France, this is a small class, but it’s well worth investigating.

- - -

Posted on 2023.05.02 in Touraine, Anjou, Saumur-Champigny, France, Wine-Aid Packages, Loire | Read more...

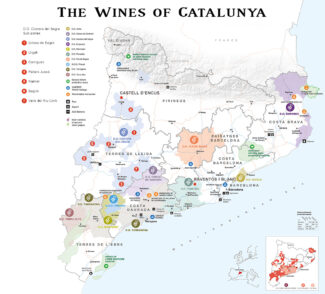

Catalunya’s New Guard: Small-Scale Artisan Couple Alemany & Corrio in Pursuit of Terroir Expression and New Qualitative Heights (5-Bottle Pack $196)

Join us for Saturday Sips

On Saturday, we will continue our tasting tour of Catalunya, this week featuring the wines of Celler Alemany i Corrio for a look at Penedès through the palates of this dynamic couple.

This is an all-day event, so come and taste whenever it is convenient!

We continue our celebration of ‘All Things Catalunya’ with a climb high into the rarefied peaks of the Penedès highlands, best known for its Cava—the Spanish response to Champagne. But two of the many maverick winemakers who dot the region, especially the Alt-Penedès, are the focus of this week’s package. Irene Alemany and Laurent Corrio will allow us take a deep-dive into a mindset that is shaking off the cobwebs of convention by producing de-classified wines on their own terms. Sometimes labeled ‘garage wines’, these wines are—despite the moniker’s association with grease and oil—small-production gems of innovation and originality.

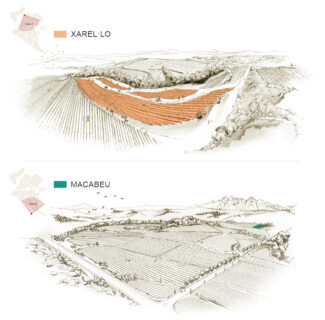

Irene Alemany and Laurent Corrio have been vinifying in Penedès since 1999, and represent two prime examples of the new thinking that has come to old wine country. Following organic principals and reducing yields while working with largely hand-crafted equipment, their simple cellar on the industrial side of Vilafranca del Penedès is producing distinctive wines from indigenous grapes like Xarel·lo and Macabeu while dabbling in interpretation of classic varieties like Merlot and Carignan—here called Carinyena—but always with a commitment to maximum fidelity to the earth on whose bounty the winery depends.

Penedès Highlands: Catalunya’s Elevated Wines

An hour southwest of Barcelona, Penedès may be best known for Cava, but the appellation refuses to be pigeonholed: The cutting-edge wines arising from the mountain vineyards are setting new standards for quality, especially the reds in an area in which nearly all the output is white.

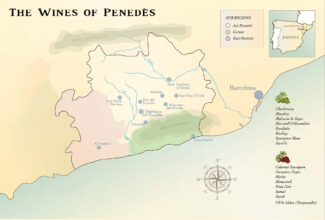

Subdivided into three regions based on elevation (the coastal Baix-Penedès, the Garraf, and the Alt-Penedès) the appellation stretches westward and inland from the Mediterranean Sea over undulations known as the Catalan Coastal Depression, where the maritime range and the pre-coastal mountains see vines thriving at 2,600 feet.

Although the dominant varieties here is Xarel·lo, one of the mandatory grapes used in Cava (along with Macabeu and Parellada), Chardonnay, Muscat, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc and Chenin Blanc are growing in popularity. Smaller quantities of red grapes cover about 10,000 acres of Penedès vineyards, dominated by Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon with the Spanish standbys, Carinyena and Tempranillo.

The climate is mostly Mediterranean, with mild winters and hot summers. But a changing climate is re-writing the book on the altitude where it is possible to grow grapes successfully in the Penedès highlands. Regardless of the weather, the soils are unchanged: The clay, sand and limestone substrates below the grapes are generally dry and friable, conducive to letting vine roots penetrate deeply.

Celler Alemany i Corrio

Maxim Fidelity to The Land

There are matches made in Heaven and those made in vineyards; credit the latter to the life partnership of Irene Alemany and Laurent Corrio, whose small-batch, low-intervention wines are proving that the Alt-Penedès is among the most exciting places to be making wine today. Great wine is a technical beast, but without the intensity of passion, it loses much of its savor: “Our wine is as soft as a gentle kiss, but one where you end by biting your partner’s lip,” says Irene.

Irene Alemany, Celler Alemany i Corrio

The couple met at the University of Burgundy in Dijon, then apprenticed together in vineyards in France and California. But their future was written in chalk and loam following a visit to Irene’s parents in Lavern in the Penedès; that was when Irene’s father suggested that they consider using the family vines to start their own operation. This treasure trove encompassed several varieties of grapes between 25 and 60 years old. They leapt at the opportunity—their first harvest was in 1999 and their first bottling in 2002. From the beginning, they followed their French training, remaking the classics in their own way, keeping the process as natural as possible while seeking to reflect the expression of the varieties and the character of the terroir to the maximum extent.

In the process, they are credited with producing the first ‘garage’ wines of New Penedès. Their ‘Vi de Garatge’ series may be thought of as ‘tailor-made’ wines relying on precision in both field and cellar.

“What we want to accomplish,” says Irene, “is that when people taste our wines there is something in the soul of the wine that talks to them and will make them remember.”

Xarel·lo: French Inspiration With a Catalan Soul

All the exotic mysteries of Catalunya may be contained within a single word, Xarel·lo, which in its correct spelling contains a diacritic scarcely known outside the region—a small dot where we have placed a dash. It’s called a ‘punt volat’—a flying point, and indicates a glottal pause. The pronunciation, somewhere in the neighborhood of ‘shah (or ‘chah)-REL-LO’ introduces you to the most aromatic of the Cava trinity; it also makes a heady, hallowed still wine that ranks among Spain’s finest whites. Not only is it delicious, the grape is rich in polyphenols and high in the antioxidant resveratrol, often associated with red grapes and the mystery behind the formerly ballyhooed ‘French Paradox.’

If it’s a variety with which you are unfamiliar, chances are good that you are even less familiar with its parentage—it is a cross between Brustiano and Hebén. But the taste is something that you will retain for a long time, especially when vinified with the Burgundian gesture that Irene and Laurent bring to their Catalan cellar, producing Xarel·lo with structure and elegant aging potential, with a savory nuttiness that has been likened to Meursault.

Celler Alemany i Corrio ‘Principia Mathematica’, 2021 Vi de Garatge ($26) White

Celler Alemany i Corrio ‘Principia Mathematica’, 2021 Vi de Garatge ($26) White

Originating with low-yields from a seven-acre plot where the vines are over fifty years old, Principia Mathematica was fermented in French oak (10% new) and aged for ten months in foudres/stainless steel. Parker’s Wine Advocate considers this the finest vintage of the 100% Xarel·lo that the Alemany-Corrios have produced. It shows crisp mineral notes behind a rich panoply of citrus fruits along with grassy hints of apricot and toasted nuts. 665 cases produced.

Celler Alemany i Corrio ‘Cargol Treu Vi’, 2021 Vi de Garatge ($31) White

Celler Alemany i Corrio ‘Cargol Treu Vi’, 2021 Vi de Garatge ($31) White

Another pure Xarel·lo beauty from the same vintage; Cargol Treu Vi comes from 75-year-old vines planted on chalky soil, then vinified on wild yeast in 300 liter French oak barrels, 25% new. The wine shows spring flowers, stone fruit and lemon zest behind hints of smoke with a long, salt-tinged finish. 175 cases produced.

Pas de Deux: Merlot with Carinyena in the Lead

Merlot is the most widely-planted red wine grape in the world; Carinyena, a.k.a Carignan, is found in quantity only along the Mediterranean coast. Still, they make such ideal wine companions that it is surprising that the blend is not more common. Merlot tends to be a fruit-driven wine with a silkiness that reaches a pinnacle in Pomerol and Saint-Émilion, but in warmer climate it seems to lack enough backbone to stand alone. Blended with Carinyena, known for its high levels of tannin, color and acidity, there is a beautiful balance that may be compared to Bordeaux’s classic Cabernet Sauvignon/Merlot matchup.

Although these wines are generally intended for early consumption, when produced using lutte raisonnée agriculture and low yields as is found in the Alemany i Corrio playbook, it makes a deeper, darker, most complex wine that can withstand time in the cellar and improve.

Celler Alemany i Corrio ‘El Microscopi’, 2019 Vi de Garatge ($26) Red

Celler Alemany i Corrio ‘El Microscopi’, 2019 Vi de Garatge ($26) Red

Another ‘garage wine’ from the Alemany-Corrio couple, the original plan was to use funds raised in sales to purchase a microscope for the Oncology Institute of the Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron in Barcelona where Irene was treated during the most difficult medical time in her life—hence, the name. 80% Carinyena and the 20% Merlot, the wine undergoes a 10-day pre-fermentation cold-soak maceration; the Carinyena ferments entirely in stainless steel while the Merlot spends time in some oak. The wine is then bottled without clarification or filtration after one year in tanks. Due to the COVID pandemic, the 2019 vintage wasn’t bottled until later. It shows an earthy nose with hints of garrigue herbs, cardamom and rich blackberry. 165 cases produced.

Celler Alemany i Corrio ‘Pas Curtei’, 2020 Vi de Garatge ($26) Red

Celler Alemany i Corrio ‘Pas Curtei’, 2020 Vi de Garatge ($26) Red

New meets old in this 40% Merlot, 35% Carinyena, 25% Cabernet Sauvignon blend from vines between 15 and 70 years old. It fermented destemmed after a five-day cold soak and matured in French oak barrels and a 1,000-liter oak foudre for 14 to 16 months. It shows rose and exotic spice on the nose, with a rich, ripe palate of cherry, blackberry and cassis intermixed with graphite, peat and light smoke. 583 cases produced.

Celler Alemany i Corrio ‘Sot Lefrìec’, 2018 Vi de Garatge ($87) Red

Celler Alemany i Corrio ‘Sot Lefrìec’, 2018 Vi de Garatge ($87) Red

Sot Lefrìec is Alemany i Corrio’s flagship red, made from a hand-sorted blend of 50% Carinyena, 30% Merlot, 20% Cabernet Sauvignon from their oldest vineyards. All grapes are manually harvested and placed in small boxes after vineyard pre-sort. At winery, they are destemmed and undergo cold-soak maceration for more than a month. Malo fermentation takes place in new and single-use oak barrels where the wine rests for 22 months. Mature, robust and intense, it displays of ripe black current, forest floor, mushroom and elegant notes of leather, with a spine of freshness provided by the Carinyena.125 cases produced.

NEW ARRIVAL

Clos Petitona

(Priorat – Vi de Vila ‘Masos de Falset’)

A Burgundian Approach

A grasp of Priorat’s wines begins with the soil, but to understand the region, it must be noted that two decades ago, Priorat was an impoverished and isolated hinterland, scarcely known inside Spain let alone by the world at large. Around the turn of this century, however, a new generation discovered Priorat’s ancient wine traditions and potential. Some of these ‘newcomers’ had been here the entire time and began to revive family wineries and old vineyards. Others, like José Mas of Costers del Priorat came, saw and earned his reputation: “Some people work in wine because they have family vineyards. I’m part of Generation Zero. I don’t have any inherited obligation to work; it’s just my passion.”

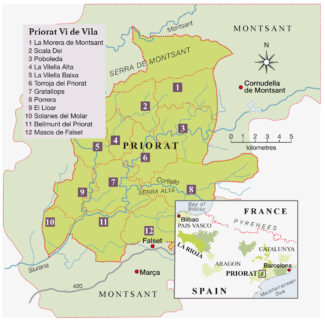

‘Els Noms de la Terra’ (The Names of the Land) is DOQ Priorat’s new, Burgundy-inspired classification system, among the most ambitious ever carried out by any Spanish wine producing region. As in Burgundy, the base of the Priorat pyramid is made of regional wines; they can be produced with grapes grown throughout the appellation and are labelled DOQ Priorat. Since the 2007 vintage, Vi de Vila (Village wine) is restricted to certain places approved by the Consejo, and following the 2017 vintage, Vi de Paratge was introduced, similar to climats or lieu-dits in Burgundy. Single-vineyard wines may be labelled either as Vinya Classificada (aligning with Premier Cru) or Gran Vinya Classificada (the equivalent of a Grand Cru).

Priorat: It’s All About The Slate

‘Llicorella’ may roll off the tongue like licorice, and that’s because the unique slate of Priorat takes its name from the famous root. It’s this feature which gives the wines of Priorat a striking minerality. Other similar metaphors can be made: Like the black version of the candy, the best Priorat wines share an inky color and a rich texture, while there is a fruity freshness in those grown at the highest altitudes on red clay.

Masos de Falset Hillside composed of ‘Llicorella’ consisting of reddish-black slate with small particles of mica quartz, different layers of soil filled in by clayey soil, Clos Petitona winemaker Blai Ferré i Just to the right.

Fresh Approach: ‘Wake-Up’ Wines and Identity

Says Valenti llagostera of Mas Doix: “Priorat wines are wake-up wines, not sofa wines.”

Given the diversity of the land, there is no likelihood of him or anyone producing a textbook or recipe wine. Yet the best Priorat wines share a clear identity, usually with an inky color and a dense, rich texture. There is often a distinct freshness typical of Garnatxa grown at the highest altitudes on Llicorella and red clay.

Clos Petitona, Priorat – Vi de Vila ‘Masos de Falset’

Unlike some labels from lesser known appellations, Priorat wines will never be inexpensive. Vineyards are tiny and working them can be brutal; they do not sell themselves in the market, and the price also reflects their relative scarcity. There are fewer that one hundred registered wineries in the entire region, far fewer than we have in Michigan.

Priorat now claims 459 ‘partages’—lieu-dit sites—with specific identifiable characteristics.

Clos Petitona, 2017 Priorat – Masos de Falset ($78)

Clos Petitona, 2017 Priorat – Masos de Falset ($78)

Clos Petitona is produced from a single plot located in the village of Falset, and is typical of the extreme slopes of the region, terraced against the ravages of time. It was planted in 1949 with equal parts Garnatxa Negra and Garnatxa Peluda vines, with a south-east orientation and a surface area of 3.5 acres. Due to the age of the vines, yields are extremely low, giving the wines superb concentration and structure. All treatments that are made in the vineyard are done using organic techniques. Fermentation takes place in thousand-liter open-top stainless-steel tanks, with punch-downs three times a day to achieve ideal extraction. Like the plot itself, Petitona is equal parts traditional Catalan Garnatxa and a variety known as Garnatxa Peluda—‘Hairy’ Garnatxa—because the vine leaves are covered in fine hairs that make it drought resistant. Perfumed rather than floral, the wine shows an earthen nose with baking spice and especially, a touch of licorice-ash, allowing the soil llicorella to live up to its name.

- - -

Posted on 2023.04.26 in Saturday Sips Wines, Spain DO, Penedes, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

Higher Grounds: Raül Bobet Transforms Practices and Traditions in a New Vineyard in The Catalan Pyrenees Mountains, Northern Spain (5-Bottle Pack $299) + Saturday Sips Returns

Join us for Saturday Sips

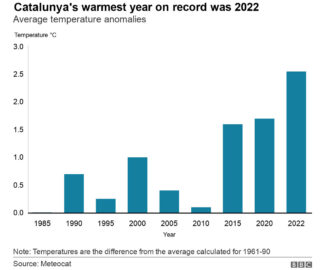

‘La Diada de Sant Jordi’ falls on April 23 in the Catalan holiday calendar, a day of books and roses, and it is a great reason to resume our all-day, in-store Saturday sips. Among the themes we will be exploring in weeks to come is ‘vinecology’—the agricultural and techno-fixes that will alter the world of wine as profoundly as global climate change is altering traditional (and non-traditional) wine growing areas.

This Saturday we will be sampling and celebrating ‘All Things Catalunya’ with a selection from the wine portfolio of Castell d’Encus.

Most winemakers provide both the brains and the brawn of their operation, but our featured enòleg, Raül Bobet of Castell d’Encus, takes it to extremes. With a degree in chemical engineering and a Ph.D. in oenology, Bobet manages three hundred lofty acres in the sub-Pyrenees where Hospitaller monks once cultivated wines—Bobet’s wines are still fermented in the ancient stone tureens carved by these holy men. An obligation to the unity between art and science and the primacy of geography forms the spiritual basis of the Bobet ethos; the wines represented in this week’s package are a paean to the variety and depth of Catalunya wines, the ‘land of castles’, whose treasury continues to amaze us with its many surprises.

The Vigneron’s Dilemma

It’s no secret that grape vines have been known to produce the best wines where the challenges are greatest. Vines placed under natural stress, struggling to find water and nutrients, tend to produce fruit that is more vibrant in flavor and balanced in acid with smoother tannins. Sites that are flat, well-irrigated and sunny—in short, no-brainer terroirs that over produce and under perform.

But with climate change putting pressure on all agricultural products, the human brain, like the farms themselves, are being put to the test. Vignerons like Raül Bobet are pulling out all stops to find innovative ways to produce quality wines in off-the-beaten-track regions that have become slightly warmer in recent decades, and thus, more hospitable to vines.

Like the old Inuit following the caribou, modern winemakers are being forced to follow the thermometer.

(Climate) Change is Afoot

With a total more than two million wine-producing acres, Spain has the largest area of vineyards in the world. It stands to reason that nuanced and sensitive agricultural products like grapes would be especially impacted by rising summer temperatures and milder, wetter winters. And according to the national weather office Aemet, over the past 60 years, average temperatures in Spain have risen by 1.3 degrees Celsius.

Says Catalan vigneron Gay de Montellà Estany, “In the past decade, temperatures have brought the grape harvest forward by 10 to 15 days. We have to harvest at the start of August when the heat is the most intense.”

As a result, timing the harvest becomes perhaps the most critical decision a modern winemaker has to make—done too early, when the grapes have not reached full phenolic ripeness, many compounds that affect aroma and flavor are not matured. Alternately, if the winemaker waits too long, the fruit has less acidity and increased sugars, resulting in higher alcohol with a profile that may come across as flabby. In either case, says Fernando Zamora, a professor in the oenology department at Rovira i Virgili University in Catalunya: “These grapes have not ripened in the right way.”

Counter or Adapt

The most delicious irony in changing weather patterns may be that as old wine appellations are dealt increasingly severe blows, regions once considered too cold for vines are warming to the point that they can produce quality wines.