Chardonnay of Steel: Unraveling the Mystery of Chablis With Domaine Long-Depaquit’s Enviable Holdings in Six Premier Crus (Pack $349) and Five Grand Crus (Pack $576)

Join Us for Saturday Sips: Chardonnay of Steel

Come as you are; come any time that’s convenient for you during our business hours to sample selection from this week’s selections. Our staff will be on hand to discuss nuances of the wines, the terroirs reflected, and the producers.

When the dog day of summer hit—earlier and earlier, it seems—the elegance and finesse of Chablis, with its unparalleled combination of lively fruit and mineral-driven crispness, is an ideal outdoor companion. Not a porch-pounder by any means, but Chablis may be the ultimate sundeck-sipper.

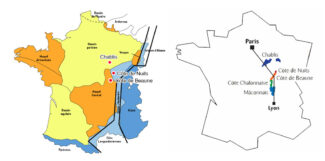

Chablis’s climate agrees; it’s cooler than most of Burgundy’s Chardonnay country because it’s further north. Its vineyards sweep down from the hillsides neighboring the diminutive namesake village of Chablis (around 100 miles north of Dijon) where Champagne-like terroir, filled with chalk, lends tension and nervy acidity to the wines and produces the mouthwatering quality that refreshes the swampiest days of summer.

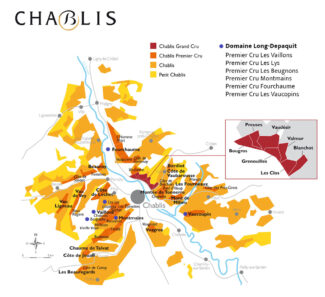

This week’s packages take a drive in the convertible through the heart of the best Chablis country—Grand and Premier Crus from Domaine Long-Depaquit, among the most reliable consistent of all producers in the appellation.

Making Chardonnay: Back to The Origins

All Chablis is Chardonnay, but not all Chardonnay is Chablis. That deceptively simple fact belies the multiple faces that this variety adopts in the relatively small confines of Burgundy—incarnations based equally on terroir and tradition. The Côte Chalonnaise and Mâconnais tend to produce balanced, approachable, subtly-oaked Chardonnays that Americans may know best from the 1990s craze of wines from the village of Pouilly-Fuissé.

The Côte d’Or, on the other hand, turbo-charges the concept by producing oaky, complex and long-lived wine. Only the most intensely-flavored fruit can stand up to this style of oak-barrel maturation, but the resulting wines are at the pinnacle of the world’s great whites.

The third style features in this week’s packages, where a cooler climate and northerly latitude barely allows the grapes to ripen, thus ensuring that Chablis makes a leaner style with higher acidity that does not lend itself to intensive oak-aging. As such, these wines are pristine, rarely seeing new oak at all, and only occasionally seeing milder, seasoned barrels to soften some of the electricity.

Chardonnay in Chablis: Acid Trip

Acidity in wine must be handled with the same circumspection as in the laboratory—make a wrong move and you end up with a wincing sting; in either case, it’s a fail. Balance is the key in all things wine, but clearly, wines from more northerly regions face a bigger struggle in balancing ripeness with sharpness, and Chardonnay is the poster-child varietal for ‘If life hands you lemons, make Chablis.’

The line between refreshing tension and acid-reflux may be fine, and one reason that aging Chablis has always been a requirement in Cru versions is that time softens acids and allows the briny, saline-driven savoriness to blossom. Nearly all Chablis undergoes a secondary malolactic fermentation prior to bottling, a technique that transforms malic acid into softer lactic acid and provides a more stable environment. Most Premier and Grand Cru Chablis also see time in neutral oak to further the mellowing process before facing the catwalk of consumption.

What Lies Beneath

“The vineyards of Chablis have a single religion,” writes Jacques Fanet in his book ‘Les Terroirs du Vin’: “Kimmeridgian.”

Kimmeridgian limestone marl – courtesy of The Source

Soil in Chablis; big chunks of Portlandian limestone on top with soft Kimmeridian limestone marls underneath.

In the middle of the 18th century, a French geologist working in the south of England identified and named two distinct types of limestone from the Jurassic Era; Portlandian, which he found in Dorset with a layer of dark marl just below it, subsequently named after the nearby village of Kimmeridge. These strata also run across the Channel and through the north of France, where they become a part of the ‘Paris Basin’ and play an indispensable role in creating the soils. A slow geological tilting of this basin allowed the Seine, Aube, Yonne, and Loire rivers to cut through the rising ridges and form an archipelago of wine areas in Champagne, the Loire Valley and ultimately, Burgundy.

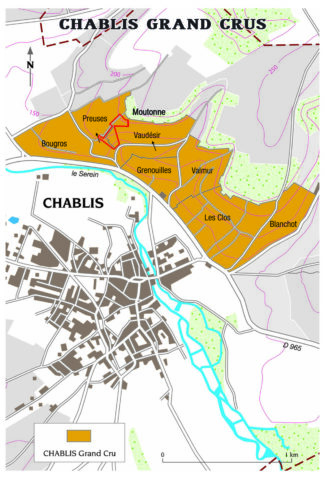

Chablis remains the biggest island in the Kimmeridgian chain and it is home to some of the finest Chardonnay terroirs found on earth. The defined region ‘Chablis’ was recognized in 1923 by the Wine Tribunals as requiring a sub-soil of Kimmeridgian limestone while wine grown anywhere else in Chablis would be classed Petit Chablis. The Grand Cru mid-slope in Chablis maps almost perfectly to the Kimmeridgian outcrop, with the soft, carbonate-rich mud rock capped by Portlandian Barrios limestone and supported by Calcares à Astarte, yet another type of limestone.

And now for the interesting part: As vital as Kimmeridgian soil is to the top Cru classifications in Chablis, it is not the primary consideration. Geologic conditions identical to those experienced by the Grand Cru slope extend both northeast and southwest, but the vineyards on those sites are classed as Premier Crus. As a matter of fact, the reference to Kimmeridgian limestone in the definition of Chablis was discontinued in 1976, a tacit admission that slope and orientation are of even greater importance to wine quality.

2020 Vintage: Superb Harvest with Outstanding Aging Potential

In 2020, the problem for Chablis was not reining in grape acid, but retaining it. Like much of Western Europe, Chablis experienced the warmest 12 months on record, warmer even than 2003. This meant an early start to the 2020 growing season and, while there were outbreaks of frost, the damage remained minor, particularly when compared to 2021.

According to Domaine Long-Depaquit’s Matthieu Mangenot, “2020 was a very easy vintage to manage. With a 40% reduction in rainfall and over 300 hours more sunshine than average, there were next to no disease issues in the vineyard. The dry weather even retarded weed outbreaks and this meant little to no spraying was required.”

One of the surprises that has emerged from persistent summer heatwaves brought about by a changing climate is a somewhat unique ability for Chardonnay to adapt without losing its sense of place. 2020 is a case in point, according to Mangenot: “Despite the heat and dryness, the alcohol levels are normal, the acidity levels are exceptional and the overall balance on the palate means the wines are representative of an excellent vintage for the region.”

Domaine Long-Depaquit

Enviable Holdings

At more than 150 acres, Long-Depaquit is one of the largest domains in Chablis, renowned and respected not only for its sprawling terroir but for a commitment to low-intervention, organic farming. In 2014, upon completion of a new winery, the estate has focused on quality improvements centered on earth-friendly approach; in 2019, the property was awarded the highest Level 3 Haute Valeur Environmentale certification.

Beaune-based négociant Albéric Bichot has managed Long-Depaquit since 1967, and the current winemaker, Matthieu Mangenot, joined in 2007, after dual training as an agronomist and an oenologist in South Africa, Lebanon, Bordeaux and especially, Mâconnais and Beaujolais. He has spearheaded the domain’s comprehensive approach to authenticity and sustainability.

Matthieu Mangenot, Domaine Long-Depaquit

Long-Depaquit produces around 180,000 bottles of Chablis each year, and like most large estates in the region, the lion’s share is village wine fermented and aged in 100% stainless-steel tanks. Wine from their six Premier Cru sites and six Grand Cru sites wines see a small percentage fermented and aged in barrels between two and five years old; Grand Cru Les Clos typically sees a higher percentage (25 to 35%) of oak.

Their flagship cuvée is Grand Cru La Moutonne, drawn from a 5.8 acre monopole vineyard that straddles two Grand Crus (95% in Vaudésir and 5% in Les Preuses) in a steep amphitheater capable of producing some of the richest, most complex wines in Chablis.

The Premier Crus: Structure With Good Length

Domaine Long-Depaquit Premier Cru Package: Six Bottles for $349

Longevity is not only a hallmark of this appellation’s palate sensation: more than half of the climats entitled to wear the ‘Premier Cru’ label had their present-day names by 1429. Chablis Premier Cru represents about 14% of Chablis production, with sites scattered on either side of the Serein River and covering around 2000 acres. As in Bordeaux, where the location of the vineyard compared to the Dordogne and the Garonne determines the style and quality of the wine, the case is similar in Chablis, where left bank wines tend to be more floral and fruit-centered whereas right bank wines are steely and mineral-focused.

Further illuminating the subject is Marc-Emmanuel Cyrot of Domaine Millet, who observes, “The right bank provides complex, well-balanced wines, with a maximum of minerality and vivacity. Those on the left bank are very aromatic, with a less full-bodied character.”

Again, as in Bordeaux, this is the result of soil, topography and exposure to the sun: On the right bank, close to the village, many of the well-known Premier Crus share similar geology, exposition and characteristics with the Grand Crus. To the left of the river, a different style emerges, with many steep-sided vineyards oriented southwest-northeast, east-facing slopes and varying ratios of limestone and clay.

Of the 40 vineyards that fall under the Premier Cru category, 17 are reckoned to be superior, or ‘flag-bearing’ climats. Among these 17, vineyard differences are pronounced and subtle, but with age, the individualism of the respective climats becomes even more apparent.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Vaillons ($52)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Vaillons ($52)

Found in a valley to the southwest of Chablis on the western side of the Serein river, a southeasterly face and high-quality Kimmeridgian soils below meld to make this large climat a sought-after location. At 318 acres, the Vaillons vineyard is made up of eight, smaller climats, all Premier Crus in their own right.

Tensile and incisive, the wine displays classic aromas of crisp green apple, citrus zest, white flowers and oyster shell with racy acids and loads of depth at the core.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Lys ($61)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Lys ($61)

Les Lys is a Premier Cru climat within the larger, umbrella Premier Cru vineyard of Vaillons. While contiguous with the latter, Les Lys has a unique aspect, bordering Séchets but facing northeast over the town of Chablis towards the Chablis Grand Cru vineyards; the rest of the Vaillons climats face generally southeast.

A textbook example of how brightly Premier Cru Chablis can shine; grilled pineapple and yellow apple on the nose with a palate of salt-preserved lemon, crushed hazelnut and fruitcake spices.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Beugnons ($56)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Beugnons ($56)

Les Beugnons is located at the western extremity of the Valvan valley on the left bank of the Serein River, where the favorable exposure is very favorable for creating expressive and charming wines.

Rich aromatics of pear peel, slight smoke, yeasty lees and candied lemon following through with a juicy palate reminisicent of ripe Mirabelle and a touch of honey.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Fourchaume ($57)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Fourchaume ($57)

Fourchaume is one of Chablis flagship climats. At 326 acres, it sprawls along the eastern banks of the Serein river where a favorable south-to-southwesterly aspect and high-quality limestone soils beget a distinctive wine with rounded citrus flavors underwritten by fresh minerality.

A crystalline, full-bodied, mineral Chablis with buttery rich notes of ripe apple and sunny Meyer lemon. Tautly-structured with a bracing acidity and a lingering finish.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Vaucopins ($62)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Les Vaucopins ($62)

Les Vaucopins is found on the right bank of the Serein River in the commune of Chichée, five miles east of Chablis. Its terroir has an uncanny resemblance to the Grand Crus, with southern exposure, steep slopes and numerous Kimmeridgian outcrops.

An elegant and refined wine that displays milk caramel notes behind nuances of oak, there is a hint of sweetness on the palate with flavors of candied fruit, apricot, and quince.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Montmains ($61)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Premier Cru Montmains ($61)

Another flag-bearing climat, Montmains also encompasses the climats of Butteaux and Forêts to cover approximately 300 acres. With a long, narrow southeast and northeast exposure, Montmains sees early morning sun, but is somewhat colder than nearby climats and usually sees a later harvest.

Lively, chalky, pure and accessible with white pepper, stone and some aniseed with a tight, linear focus, the wine is taut and refined with a wonderful finish.

The Grand Crus: Keeping Potential

Domaine Long-Depaquit Grand Cru Package: Five Bottles for $576

The ne plus ultra in the region, Chablis Grand Cru, represents only about 1% of total Chablis production; it is comprised of seven climats within the commune of Chablis itself and in the hamlets of Fyé and Poinchy on the right bank of the Serein River, which runs to the northeast of the village of Chablis. The names of the vineyards (Blanchot, Bougros, Les Clos, Grenouilles, Preuses, Valmur and Vaudésir) feature prominently on labels due to the distinct characteristics of each, and are found at elevations between 325 and 825 feet for a total of about 250 acres.

The signature of a Grand Cru Chablis is the perfect balance of fruit-based fattiness and bracing acidity; it is a refreshingly dry wine with nuances based on the individual vineyard, but the common notes to expect include the elusive scent of freshly-sliced mushrooms and a discreet touch of honey. Most impressive in a wine with limited exposure to the preservative qualities of oak is its ability to age and improve, ten years minimum with fifteen years or more well in the realm of possibility. With maturity, the earthiness and nutty-qualities of Grand Cru Chablis increase as forward citrus fruit fades and an intriguing spiciness takes over.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Bougros ($102)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Bougros ($102)

Bougros is located at the northwestern edge of the Grand Cru hillside; it covers nearly 39 acres of slop on the Right Bank of the Serein and tends to produce wines that are considered, rounded and less austere in youth than those from the other Grand Cru climats.

Silky and expressive, the wine offers brioche, toast and ripe green apple with petrol, dried peach and shellfish nuances.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Vaudésirs ($127)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Vaudésirs ($127)

At the heart of the Grand Cru area, the Vallée des Vaudésirs is a textbook example of the geology and history of Chablis, bearing witness to the erosion that followed the last ice age. Long-Depaquit’s vineyard is more than forty years old, planted in the ‘endroit des Vaudésirs’, where, beneath steady sunshine, Kimmeridgian outcrops are the most numerous.

The wine’s bouquet is redolent of citrus fruit and delicate lily and chamomile notes while the palate offers green apple notes, hint of white peach and a hint of coastal herbs.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Preuses ($110)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Preuses ($110)

The 29-acre Preuses slopes continue from those of the Bougros climat at the bottom of the hill, becoming increasingly steep toward the top. At the northern end of the Grand Cru slope, the Kimmeridgian soils and a sunny aspect make for an excellent terroir, but the wines tend to be rich and elegant, if less aromatic than other Chablis Grand Cru wines.

The wine is steely and rich with a gunflint character behind softer floral tones and hazelnut notes.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Clos ($127)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Clos ($127)

At 65 acres, Les Clos is by far the biggest Grand Cru climat in Chablis. Its southwest exposure, offering perfect sun, combines with a relatively steep slope to provide optimal ripening conditions. Because of its size, Les Clos’ soil is multi-faceted: towards the top, stones and limestone become more prevalent, whereas towards the bottom, on the contrary, it gets deeper with more clay.

The wine blends two plots and reflects the specificity—the bouquet combines floral notes from the higher of the two plots with almond and hazelnut notes from the mid-slope vineyard.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Blanchots ($110)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Blanchots ($110)

Blanchots provides a unique soil composition, combining typical Chablis Kimmeridgian limestone with ammonites and a layer of white clay. Blanchots takes its name from this white clay. which retains moisture and protects the vines from hydric stress.

The wine shows a floral nose dominated by lilies and white roses; the ample mouth is generous with citrus and stone fruit, leading to mineral fish with hints of flint and graphite.

Chardonnay Finds Valhalla

Chablis Grand Cru ‘Moutonne’

Domaine Long-Depaquit ‘Monopole’

When the Burgundian wine trade refers to a ‘monopole’, it refers to a single defined vineyard area responsible for the production of a single label from a particular producer. La Moutonne is one such vineyard, six acres in size and lying mostly within the Vaudésir Grand Cru, but with a small protrusion into Les Preuses. Owned entirely by Domaine Long-Depaquit, itself owned by Domaines Albéric Bichot, Moutonne faces predominantly south, although with the gentle curve of the hillside, some of the vines face to the southeast. Coupled with a relatively steep gradient that increases sunlight exposure and drainage, the vineyard enjoys a warmer mesoclimate than vineyards lower down the slope.

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Moutonne ‘Monopole’ ($229)

Domaine Long-Depaquit, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Moutonne ‘Monopole’ ($229)

25% of this wine sees neutral oak for ten months, then final ageing in stainless steel vats for six months on fine lees. The nose is fleshy with peach and nectarine, with discreet notes of jasmine and violet. Full-bodied and generous with the distinct marly minerality that reflects the micro-terroir, the palate maintains freshness and lightness despite the complexity.

Chablis Grand Cru ‘Les Blanchots’

Domaine Laroche ‘Réserve de l’Obédience’

From its headquarters at the Obédiencerie of Chablis, Laroche celebrates a heritage dating back to the Middle Ages, when the Canons of St. Martin of Tours were making wine. St. Martin’s relics were hidden in the Obédiencerie for a decade and Domaine Laroche still produces and ages its Premier and Grand Crus in these historical cellars.

At well over two hundred acres situated among the top vineyards in Chablis, the estate’s approach to maintaining terroir specificity is unique: Under the direction of Grégory Viennois, the winemaking team designate one team member to each plot who is wholly responsible for the management of that vineyard from pruning and health of the soil to the quality and quantity of fruit yields. According to Viennois, “We tend to be fatalists. If the weather and the climate are not with us, we can do very little, so we have learned to work with the weather. We have rainfall and steep slopes, and this defines our terroir and wine.”

Grégory Viennois, Domaine Laroche

The heralded star in the Laroche portfolio is cuvée Reserve de L’Obédience, which draws the best fruit of the Les Blanchots Grand Cru. The pinnacle of Laroche holdings, Les Blanchots provides a unique terroir made of a layer of white clay on Kimmeridgian limestone with ammonites—an ideal admixture that maintains the optimal amount of water for deep root development. Combined with a southeast exposure, this allows for slow ripening and gradual aroma development slowly, just as the wine requires about five years to fully express itself.

Gilding the Lily 101: We know what to do when life hands us lemons, but when the vineyard hands us Grand Cru crop, the options are interesting. Technical director Grégory Viennois explains the steps involved in creating the Laroche pinnacle, ‘La Réserve de l’Obédience’:

“The grapes are hand-harvested in Grand Cru Les Blanchots and collected in small crates to go to the winery, where they are sorted. Then, each parcel is kept apart in order to do the entire winemaking process separately. Blending of the best wines from Grand Cru Les Blanchots takes place at the beginning of the summer every year—samples are taken from each vat, cask and barrel and are then tasted and selected for their delicacy and silky outlines. The aim is to express in the glass the typicity of the terroir as faithfully as possible. We try to get nearer to the perfect wine if it exists: refined, intense, mineral and capable of maturing for at least twenty years.”

Domaine Laroche ‘La Réserve de l’Obédience’, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Blanchots ($221)

Domaine Laroche ‘La Réserve de l’Obédience’, 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Les Blanchots ($221)

Regardless of vintage La Réserve de l’Obédience is a delicate and subtle wine that showcases a markedly different style in its youth than in its maturity. Up to five years, the white fruit aromas, the mineral-driven finish and the extraordinary freshness remain front and center. With a few more cellar years, the inherent richness of terroir is expressed at its best and the soft spices and acacia honey notes, still supported by the freshness, emerge to center stage.

NEW ARRIVALS

Saint-Émilion’s White Unicorns

Defining the right bank in Bordeaux is complicated; there are two major rivers and an estuary, and that’s a lot of ‘right bank’. The right bank of the Dordogne covers the traditional red wine enclaves of Saint-Émilion, Pomerol and Fronsac.

Just as with the Médoc , any white wines made here take the Bordeaux Blanc appellation, Vin de France or IPG Vin de l’Atlantique. Known as ‘the land of a thousand châteaux’ (due to an average estate size under 20 acres) white wine remains a relatively scarce commodity in the prestigious estates of Saint-Émilion, as producers struggle to justify charging as high a price for white wines as red. Of the ten ‘right bank’ appellations, including the Saint-Émilion satellites and Lalande de Pomerol, none are applicable to white wines. In Saint-Émilion, white wine is often made ‘off-piste’—from vineyards on the periphery of the appellation itself, but there are some exceptions. Most notable, perhaps, is the estate whose name is more famous than the appellation: Château Cheval Blanc.

Château Cheval Blanc

Château Cheval Blanc is a spectacular tapestry woven from a patchwork of gravel and clay soils that are closely interwoven over 45 parcels. The exceptional terroir originates in the area between Saint-Émilion and Pomerol, where Cabernet Franc and Merlot complement each other and grow in harmony across the estate’s hundred vineyard acres, which attained the supreme distinction of the Premier Grand Cru Classé A classification in 1954—only of only five wine-producing châteaux of right bank Bordeaux to do so.

Cheval Blanc (‘white horse’ in French) has always been a bit iconoclastic; in 1860, before the château itself was even finished, they had added a state-of-the-art drainage system to their vineyards that is still in use today. Adding to that, in Cabernet Sauvignon country, 58% of their vineyards are Cab Franc.

White wines from the château have an interesting origin; the vines were formerly within Château La Tour du Pin Figeac and were purchased in 2006 after La Tour du Pin Figeac lost its classified ranking in Saint-Émilion. Experiments with white wine on a small area began in 2008 as the Cheval Blanc team field-grafted three different clones of Sauvignon Blanc. In the most recent 2012 St-Émilion re-classification, three-and-a-half acres were redrawn to be included within the footprint of Château Cheval Blanc itself, leaving 16 acres for white wines. Today, that vineyard is 80% Sauvignon Blanc and 20% Sémillon.

Château Cheval Blanc ‘Le Petit Cheval Blanc’, 2020 Bordeaux Blanc ($199)

Château Cheval Blanc ‘Le Petit Cheval Blanc’, 2020 Bordeaux Blanc ($199)

82% Sauvignon Blanc and 18% Sémillon, the 2020 is considered by many to be the estate’s best white wine yet. Still young, but quite drinkable with a bit of aeration with aromas of grapefruit, white peach, lemon zest, tarragon, mandarin blossom, stony flint, and sea spray. Finely-etched acidity and a very long, mineral-driven finish.

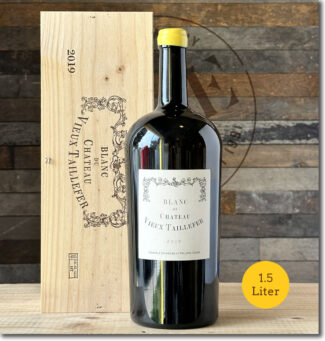

Château Vieux Taillefer

Is it possible to have your heart in the cellars of Bordeaux and your hands in the soils of Burgundy? Likely not, but the husband/wife team of Phillipe and Catherine Cohen may come close. With as impressive a Bordelaisian pedigree as exists, they have nonetheless chosen to bottle their Saint‐Émilion red wines based on soil rather than the old hierarchical system normally employed in Bordeaux, a of a ‘First’ and ‘Second’ wine.

As for their background, Catherine was studying oenology when she had an opportunity to intern under the legendary Jean Claude Berrouet, head winemaker at Château Petrus. Recognizing her talent, Jean Claude ultimately put her in charge of La Fleur Petrus, where she made wine from 1995 to 2001. After that, she worked as a consultant for many châteaux throughout Bordeaux.

Phillipe, who spent a decade as a négociant in Saint Émilion, shared her dream of opening a winery, and when the 12-acre Vieux Taillefer estate came on the market, they snapped it up.

Says Phillippe: “The property is perched on the banks of the Dordogne River and planted mostly to Merlot, with a small amount of Cabernet Franc and white varietals as well. The majority of the vines were planted in the 1950s, and when we took official ownership just before the 2006 harvest, we found that they had been tended very well, so the potential to do something great was already here.”

Catherine adds, “All our fruit is hand-harvested and undergoes careful sorting before it is vinified in concrete tanks. The work here is 100% organic, thus there are no chemicals used in the vineyards or the winery. There is no fining or filtration, and we employ no consultants. The aim is to produce wines entirely reflective of a great terroir.”

Blanc du Château Vieux Taillefer, 2018 VdF Bordeaux Blanc ($75)

Blanc du Château Vieux Taillefer, 2018 VdF Bordeaux Blanc ($75)

An iconic blend of five grapes. Merlot (the only existing white Merlot vines of the appellation), Sauvignon Blanc, Sémillon, Muscadelle and Chasselas from a plot of 75-year-old vines located in Saint-Christophe des Bardes in the heart of the Saint-Émilion appellation. Vinified and matured in slightly toasted new-oak, 300-liter, cigar-shaped casks. The wine is bottled as Vin de France, or table wine, because the appellation name strictly covers red wine.

Blanc du Château Vieux Taillefer, 2019 VdF Bordeaux Blanc ($180) en magnum

Blanc du Château Vieux Taillefer, 2019 VdF Bordeaux Blanc ($180) en magnum

Floral notes emerge on first nose, followed by beautiful grapefruit-pith bitterness and a salinity that calls to mind an ocean breeze. This is specific to the great limestone soils where the very best French whites are produced.

- - -

Posted on 2023.06.10 in Chablis, France, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

The Champagne Society June 2023 Selection: Champagne Laherte Frères

Champagne Laherte Frères

The Talented Aurélien Laherte’s

‘Quest for The Perfect Alchemy’

Due to the limited quantities of each cuvée members will be assigned one of the following four cuvées:

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Longue Voyes’, 2018 Chamery Premier Cru Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut ($83)

OR

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Vignes d’Autrefois’, 2018 Chavot & Mancy Extra-Brut ($83)

OR

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Empreintes’, 2016 Chavot Extra-Brut ($87)

OR

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Beaudiers’, nv Chavot Extra-Brut Rosé de Saignée ($83)

The traditions of Champagne makers may seem bedrock, but as time folds new players into the mix, those traditions are in constant flux. Some fall out of fashion, only to be revived by a newer generation. Aurélien Laherte, who took over Laherte Frères of Chavot in 2005, and gave a new dimension to the estate, replanting heritage varieties and moving toward organic and sustainable agriculture. Aurélien says, “We began experimenting with cover crops and higher canopies, and updating the winery facilities. Our vins clairs are now vinified in tank, foudre and barrel—the latter purchased used from Beaune’s Benjamin Leroux, and the wines are minimally dosed and closed with Diam Mytik corks, of which we were early adopters.”

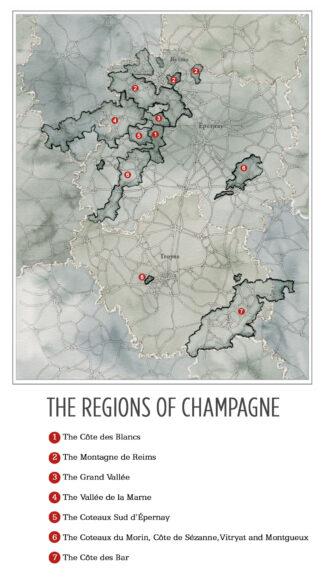

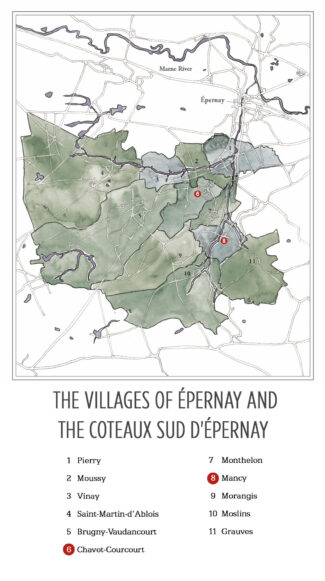

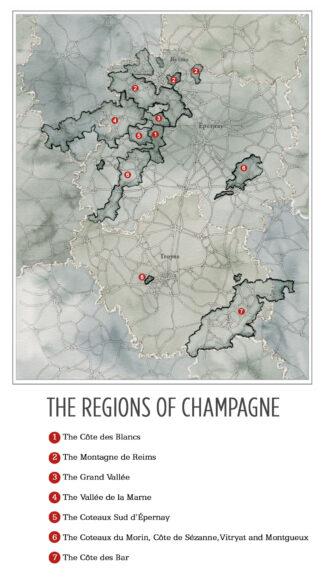

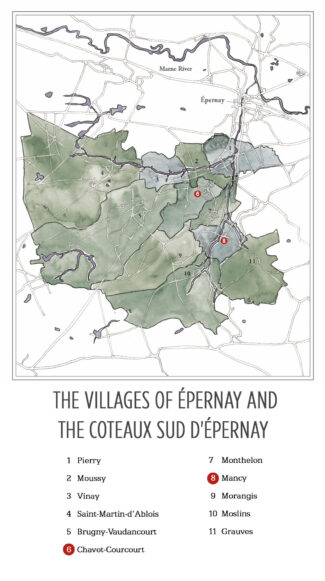

The result is clear, chiseled Champagnes that are created with the sole intention of reflecting the nuances of the plot in which they originate. The estate, with 75 parcels situated in three distinct areas (the southern slopes of Épernay, the Côte des Blancs, and the Marne Valley) is centered in the village of Chavot in the Côteaux Sud d’Epernay. They produce around 150,000 bottles a year, and this week’s offering contains a cross-section of the most outstanding.

The Coteaux Sud d’Épernay: Between Two Giants

The Coteaux Sud d’Épernay is Pinot Meunier-rich, with 47% of its 3000 acres planted to this variety, which is sometimes imagined as an ‘also ran’ in Champagne. In fact, Meunier is suited for soils that contain more clay and in terroirs with harsher climatic conditions since it buds late and makes it more resistant to frost. Sandwiched between the powerhouse wine regions Côte des Blancs and Vallée de la Marne, the Coteaux has an identity removed from either one; its terroir is distinctly different from the clay-heavy soils of the Marne and lacks the chalk of that puts the ‘blanc’ in the Côte des Blancs.

Phrasing it succinctly is Laherte Frères proprietor Aurélien Laherte: “Our wines show more clay influence than those of the Côte des Blancs and they are chalkier than the wines of the Vallée de la Marne.”

In short, these Champagnes are uniquely situated to offer the best of both worlds. As a result, the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay has long fought for recognition as entity unto itself, not necessarily a sub-region of its big brothers on either side.

Champagne Laherte Frères

Terroir Fundamentals: Preserving Its Details

That Champagne is, above all, a style of wine should be obvious, but a common misinterpretation (fueled in part by tradition and in part by marketing) removes it from viniculture and places it on a pedestal of the imagination. Nothing wrong with this, of course, so long as the ground floor remains intact.

Aurélien Laherte, along with his high school friend Raphael Bérèche, would like to see these ideas put into context. A group of Champagne’s more progressive producers, including Agrapart, Marie-Courtin, Vincent Laval and Benoît Lahaye, gathers each spring to taste the ‘vins clairs’—wines meant to become Champagne, but having not yet undergone the bubble-creation process. These are not necessarily ‘still wines’ in that they are not meant to stand on their own merits, but have terroir-transparency profiles to make them suitable for top-shelf sparkling versions.

The Laherte stamp-of-approval was placed on Champagne’s brow many years ago: Founded in 1889 by Jean-Baptiste Laherte, the estate was originally made up of vines grown in and about the village of Chavot. With his wife Cécile, fourth-generation vigneron Michel Laherte expanded the holding, modernized the press and tanks, and may be credited with realizing that the use of herbicides and pesticides prevents full terroir-expression in the wines. The philosophy of hand-working the soils, gently vinifying the juices, and remaining humble and patient as the wines develop became the foundational theme of the estate and endures to this day.

Situated largely in the Côteaux Sud D’Épernay, Laherte vineyards themselves total 26 acres subdivided into 75 separate parcels. Seven of these are farmed biodynamically and certified organic, with the rest farmed either ‘uncertified organic’ or sustainably. Each produces detailed wines that the estate seeks to showcase individually.

Aurélien Laherte, Champagne Laherte Frères

Aurélien Laherte took over in 2005 and is today considered to be one of the most dynamic vignerons in the appellation. From the multiple individual parcels, the estate produces a series of tiny production, single-vineyard, single-vintage cuvées (around 3,000 bottles each) from some of their most unique and expressive biodynamically-farmed parcels. Many of these wines are fermented and aged in used Burgundy barrels, without malolactic, and are bottled without fining and filtration. They are then finished with little or no dosage so as to not mask the individuality of the underlying terroirs.

Aurélien and his parents are registered as a négociant all the fruit grown by an extended family can be incorporated into his blends. “This is,” says, “the best way to contend with complicated French inheritance laws and keep the estate whole.”

The team, Aurélien upper left

Great lengths are taken to ensure each vine fully expresses itself and its underlying terroir. A team of ten, including aunts, uncles, and cousins, works throughout the year (in accordance with the lunar calendar) to employ techniques such as plant infusions to improve the vine’s natural defense system, and high foliage to encourage photosynthesis and thus, balanced maturity.

Village Chavot: Diversity of Soil

The commune of Chavot-Courcourt consists of Chavot (in the northeastern part of the commune) and Courcourt (in the central part of the commune), but also the small villages Ferme du Jard, Les Fleuries, La Grange au Bois, and Le Pont de Bois. Among the many folds and hills in the area, the upper reaches are clay-dominant while the soils turn chalkier as you descend. Most of the vineyards in Chavot-Courcourt are located in the northern part of the commune, on slopes formed by the stream Le Cubry.

Aurélien Laherte explains why he farms so many individual parcels in a relatively small area: “Below the village especially is a significant difference in soil types. I have identified 27 terroir-types in Chavot-Courcourt alone and farm 45 parcels. There is no sand, but there is virtually everything else—from chalk to clay to limestone. Between them are countless fine-grained distinctions, so I treat them individually and vinify them separately.”

Les Beaudiers is a vineyard in Chavot where Laherte Frères has old vines of Meunier (planted in 1953, 1958, and 1965) that are used for a rosé saignée. Other vineyard sites in Chavot-Courcourt include Les Charmées, Les Chemins d’Epernay, Les Monts Bougies, Les Noelles, La Potote, and Les Rouges Maison, all used by Laherte Frères for their Champagnes Les Vignes d’Autrefois and Les Empreintes.

Although Meunier is the dominant grape variety, Laherte also owns a vineyard called ‘Les Clos’ where he plants all seven legally allowable Champagne grape varieties. From this he concocts the individual-vinification philosophy by picking and pressing all seven varieties together.

Single Variety (Monocépage): Burgundy Comes to Champagne

Bordeaux, and indeed much of Champagne, blends grape varieties to create signature ‘house’ wines. In Burgundy, the thinking is different: Burgundies are primarily monocépages, meaning they are made from a single grape variety, often sourced from a single vineyard. In Bordeaux, the monocépage concept is virtually unknown, but in Champagne, most prominent producers will offer at least one or two in their portfolio, Blanc de Noir or Blanc de Blanc. Frequently they are vintage cuvée produced only in years where a special set of conditions are met and only released in limited quantities.

• Blanc de Blancs

Blanc de Blancs—a term found only in Champagne—used to refer to Champagne produced entirely from white grapes, most commonly Chardonnay. Pinot Blanc and Arbanne can also be used, as well as a number of other varieties permitted in the appellation, but these are much less common.

Chardonnay – ‘Emblematic Cuvée’

In Chardonnay Muscaté this mutation of Chardonnay is a genuine thing; it is grown somewhat extensively in New York state and Ontario under the name Chardonnay Musque and shows an exotic flavor profile that includes tropical fruit notes and cinnamon-tinged lemon sorbet.

Champagne Laherte Frères, nv Chavot & Épernay ‘Blanc de Blancs’ Brut-Nature ($53)

Champagne Laherte Frères, nv Chavot & Épernay ‘Blanc de Blancs’ Brut-Nature ($53)

From the chalkiest soils on the south slopes of Épernay and the Côte des Blancs, where Chardonnay vines average 35 years, Laherte hand-picks the grapes and ferments the juice in small foudres and barrels, relying on few bâtonnages. It is assembled using 50% reserve wines from previous vintages aged in barrels on lees; hence, the non-vintage label. Malolactic fermentation is partial and disgorgement is done by hand, without dosage. As a ‘non-dosé’, the wine is filled with shivery acidity, showing citrus and apple peel with accents of ginger and finishing with crushed rock minerality. Disgorged February 2022.

*click on photo for more info

Petit Meslier – ‘Vibrant and Expressive’

Petit Meslier is a somewhat rare white-wine grape grown in small quantities in Champagne. It is noted for its heat resistance and ability to maintain acids during long spells of hot weather and when vinified as a monocépage, provides tremendous aromatic intensity and depth.

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Petit Meslier’, nv Chavot Extra-Brut ($120)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Petit Meslier’, nv Chavot Extra-Brut ($120)

In creating his iconic, all-inclusive blend ‘Les 7’, Aurélien was particularly struck by the ability of his Petit Meslier to stand on its own. From a vineyard called ‘Cépages Oubliés’, it is blended with 40% reserve wine and aged for six months on its lees ‘fût de chêne’, or in oak barrels; it shows honeyed pear, buttered toast and toasted almonds behind an unsurprisingly racy spine of acidity. Disgorged December 2021.

• Blanc de Noirs

In Champagne, Blanc de Noirs mean that the wine is made from either Pinot Noir or Meunier (or a blend of the two), although it’s relatively common to find 100% Pinot Noir. Despite the ‘Noir’, they may be notably ‘Blanc’ since both Pinot Noir and Meunier are red-skinned, white-fleshed grapes that produce clear juice. Without being given time to macerate on the dark skins, the wine will be white.

Pinot Noir – ‘Intense and Straight’

Pinot Noir accounts for 38% of the area under vine in Champagne and is the dominant grape in Montagne de Reims and Côte des Bar. It is frequently referred to as ‘Précoce’ due to its tendency to ripen early, leaving behind the acidity so prized by Champagne makers. It thrives in cool, chalky soil—a hallmark of Champagne’s terroir.

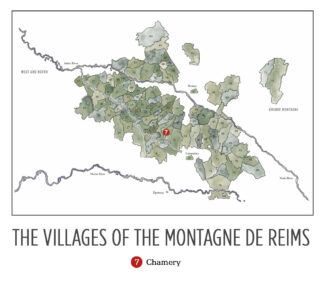

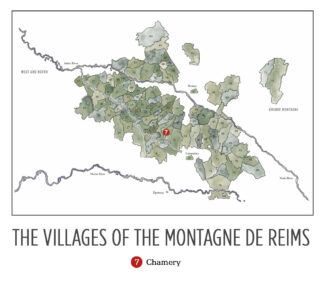

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Longue Voyes’, 2018 Montagne de Reims (Premier Cru Chamery) Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut ($83)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Longue Voyes’, 2018 Montagne de Reims (Premier Cru Chamery) Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut ($83)

Part of Aurélien Laherte’s’ Terroirs’ series, this is his first Blanc de Noirs Champagne made entirely from Pinot Noir. The fruit comes from the village of Chamery on the Petite Montagne de Reims, nearly twenty miles from the estate—hence the name, which means ‘The Long Way’. Barrel aged for 18 months with a 4 g/l dosage and no malolactic, the nose reveals notes of black fruits, and the palate is lively, tense, tasty and tonic with a persistent saline finish. Disgorged December 2021.

*click on photo for more info

Meunier – ‘Celebrating the Variety’

Traditionally used as a blending grape, there are about 26,000 acres of Meunier planted in Champagne, and the variety is rapidly becoming more than an afterthought used for color and balance. In the right soil conditions (calcareous clay with deeper chalk layers) and if allowed to ripen well (leapfrogging the vegetal stage) it can produce a wine that ages remarkably, showing finesse and freshness even after years in the bottle.

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Vignes d’Autrefois’, 2018 Chavot & Mancy Extra-Brut ($83)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Vignes d’Autrefois’, 2018 Chavot & Mancy Extra-Brut ($83)

The selected Meunier plots for this wine were planted by the Laherte family between 1947 and 1953 in the villages of Chavot (lieux-dits La Potote and Les Rouges Maisons) and Mancy (lieu-dit Les Hautes Norgeailles). Some of the vines were planted on French rootstock while others are the result of old massal selection. Aurélien uses traditional wooden Coquard presses; fermentation occurs with native yeast in old Burgundy barrels and malolactic fermentation does not take place. The wine ages up to 19 months on the lees and dosage is between two and four grams per liter; it exhibits marvelous aromas of white peach, violets and verbena. Disgorged November 2021.

*click on photo for more info

• Rosé

Credit Madame Clicquot for revolutionizing the (then) relatively small production of pink Champagne. A believer in the idea that a wine should flatter both the eye and the palate, the Grande Dame broke with tradition and re-created the process of making rosé champagne. Before, it was made by adding an elderberry-based mixture to white champagne, but Madame Clicquot had had vines in the Bouzy region of Champagne where she made her own red wine, and she decided to blend this with her still white wines.

This is the most common method of producing rosé Champagne—blending clear white and black grape musts, using between 5 and 15% red wine; it is called a rosé of ‘assembly’. The proportion of red wine can vary, but the white wine must be the majority. Another method of rosé production is the ‘saignée’ method, which involves allowing the must to undergo minimal skin contact, generally for only a couple of hours. This minimal maceration allows the must to develop stronger aromas and flavor profiles while deepening the color. ‘Saignée’ translates literally to ‘bleeding’, which is essentially what the skins are doing for the juice.

Meunier – ‘Strong Identity’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Rosé de Meunier’, nv Chavot & Vallée de la Marne (Le Breuil & Boursault) Extra-Brut Rosé d’Assemblage ($54)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Rosé de Meunier’, nv Chavot & Vallée de la Marne (Le Breuil & Boursault) Extra-Brut Rosé d’Assemblage ($54)

100% Meunier, the wine is sourced from vineyards in Chavot and Vallée de la Marne (lieux-dits Le Breuil and Boursault) with an average age of 25 years for the Meunier vinified white and more than 40 years for the parcels selected for the red wine. It is a blend of 30% macerated Meunier, 60% white wine from Meunier and 10% still red Meunier. As a result, it uses both methods of Champagne rosé creation, assemblage (blending) and saignée (bleeding). The wine is multi-layered with a ripe core of red fruit and brisk girdling acids. Disgorged March 2022.

*click on photo for more info

Meunier – ‘Varietal Complexity and Nuances’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Beaudiers’, nv Chavot Extra-Brut Rosé de Saignée ($83)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Beaudiers’, nv Chavot Extra-Brut Rosé de Saignée ($83)

100% Meunier from the ‘Les Beaudiers’ lieu-dit, planted in 1953, 1958 and 1965 on shallow clay and silty soil with chalk beneath. As always, Laherte’s methods include organic maintenance, short pruning for a limited production and regular ploughing. Fermentation takes place in old Burgundy barrels and hand-disgorgement with 0 to 4.5 g/l. The wine shows creamy red cherries, kirsch, buttered toast with strawberry jam and a bright, flinty spine. Disgorged November 2021.

*click on photo for more info

Blending: A Tapestry of Few Threads

Champagne should illustrate the word ‘synergy’ above all, where the sum of the total is greater than the individual parts. The ideal blend should be the aggregation of positive components; every thread should add to the tapestry’s whole. The blend should always drive toward harmony; Chardonnay is often up front, while Pinot Noir supplies the middle and finish. Other allowable varietals should only appear if they contribute to the primary blend.

This is not a universal outcome, of course, and according to Jean-Marc Lallier of Champagne Deutz, “Some winemakers do not blend; they mix.”

When cellar masters do it right, it is a painstaking undertaking; every tank, barrel and vat is tasted countless times to assess which batch would enhance which. This is the true art of Champagne making—the intimate familiarity with each component in order to align them perfectly.

At Laherte, Aurélien does not have a recipe for a single wine; he blends according to the call from the barrel and each blend has a trademark distinction. He prefers very low dosage, insisting that the wine’s minerality must speak first. Regarding the tedious art of blending, he says, “They’re like people; one needs to be strong, one of them weak; one bitter, one elegant.”

‘Highlighting Chavot’s Terroir’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Empreintes’, 2016 Chavot Extra-Brut ($87)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Empreintes’, 2016 Chavot Extra-Brut ($87)

From two parcels in the Chavot lieux-dits Les Chemins d’Épernay and Les Rouges Maisons, each (in Aurélien’s words) ‘exemplifying the quintessence of the Chavot terroir.’ The wine is a classic Champagne blend, half Chardonnay, (of which one-third is Chardonnay Muscaté) from Les Chemins d’Epernay where there are clay soils with a little silt stratum in surface and a chalky subsoil—vines planted in 1957. The other half is Pinot Noir from Les Rouges Maison where the soil is fairly deep with a vital presence of clay, flints and schists; these vines were planted in 1983. With a dosage of 3.5 g/l, it is a resonant Champagne with floral top notes and deftly balanced acidity. Disgorged January 2021.

*click on photo for more info

‘Return to Basics’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Ultradition’, nv Extra-Brut ($48)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Ultradition’, nv Extra-Brut ($48)

60% Meunier, 30% Chardonnay, 10% Pinot Noir from vineyard plots in the Côteaux Sud d’Épernay, Vallée de la Marne and Côte des Blancs where vines average around 30 years. The wine ages in barrels for six months and given light filtration before bottling during the spring time; 6-8 gr/l dosage. The wine offers a complex bouquet of dried apple and toasted walnut; the Meunier lends floral tones and an upper-register smokiness. Disgorged November 2021.

*click on photo for more info

‘Tribute to Yesterday’s Wines’

The system of maturation used for Sherry, the famous fortified wine of Jerez, is a cry for consistency from vintage to vintage. The soléra (or perpetual cuvée) system involves removing wine for release from the last of a series of barrels that contains a blend of every vintage since the solera was started. The void in those barrels is then filled with wine from another series of barrels, and so on, until there is room in the youngest series of barrels. The wine from the most recent vintage is added to those barrels.

In Champagne, the method used is slightly different; after each harvest, wine is added to the blend, and every time a producer is ready to release a new batch of non-vintage Champagne, he/she removes what he/she needs. Over time, the cuvée becomes increasingly complex as the fresh wines of the latest vintage taking on the mature qualities of those that came before it. It is a system used by surprisingly few producers in Champagne, but Laherte Frères is one of them.

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les 7’ Soléra 2005 to 2018, nv Chavot Extra-Brut ($120)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les 7’ Soléra 2005 to 2018, nv Chavot Extra-Brut ($120)

As the name suggests, all seven allowable Champagne grapes are used in this single cuvée; 10% Fromenteau,18% Chardonnay, 18% Meunier, 15% Petit Meslier, 8% Arbanne, 14% Pinot Noir and 17% Pinot Blanc from a vineyard planted by Thierry Laherte in 2003. He picks and presses all seven together and employs his perpetual cuvée: ‘Les 7’ contains wine not only from the current vintage, but draws bits of reserve wine from all harvests dating back to 2005, the year Aurélien took over the domain. All bottles are disgorged by hand with a dosage of 3 g/l. The wine shows lemon zest, crystalline green-apple candy and floral notes in a stony infrastructure. Disgorged January 2021.

*click on photo for more info

- - -

Posted on 2023.06.01 in France, Saturday Sips Wines, The Champagne Society, Champagne, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

When to Blend … or Not. The Talented Aurélien Laherte’s ‘Quest for The Perfect Alchemy’ in Champagne’s Coteaux Sud d’Épernay + Saturday Sips

Join Us for Saturday Sips: Beaujonomie By Beaujolais

Beaujonomie is a portmanteau, a likely blend of ‘Beaujolais’ and ‘bonhomie’—or perhaps it’s ‘gastronomie’. Either way, it’s ironic, because in Beaujolais, blends are rare, and for the most part, Gamay is what you see and Gamay what you get. But the soul of Beaujolais is easy and fun, and ‘Beaujonomie’ encapsulates the light, warm-season feel that a cool glass of Beaujolais brings to the summer table. The French celebrate a festival of Beaujonomie for three days in June; our celebration begins this Saturday with a Beaujolais tasting. Join us during business hours for a sample of an old favorite or a new discovery.

The traditions of Champagne makers may seem bedrock, but as time folds new players into the mix, those traditions are in constant flux. Some fall out of fashion, only to be revived by a newer generation. Aurélien Laherte, who took over Laherte Frères of Chavot in 2005, and gave a new dimension to the estate, replanting heritage varieties and moving toward organic and sustainable agriculture. Aurélien says, “We began experimenting with cover crops and higher canopies, and updating the winery facilities. Our vins clairs are now vinified in tank, foudre and barrel—the latter purchased used from Beaune’s Benjamin Leroux, and the wines are minimally dosed and closed with Diam Mytik corks, of which we were early adopters.”

The result is clear, chiseled Champagnes that are created with the sole intention of reflecting the nuances of the plot in which they originate. The estate, with 75 parcels situated in three distinct areas (the southern slopes of Épernay, the Côte des Blancs, and the Marne Valley) is centered in the village of Chavot in the Côteaux Sud d’Epernay. They produce around 150,000 bottles a year, and this week’s offering contains a cross-section of the most outstanding.

The Coteaux Sud d’Épernay: Between Two Giants

The Coteaux Sud d’Épernay is Pinot Meunier-rich, with 47% of its 3000 acres planted to this variety, which is sometimes imagined as an ‘also ran’ in Champagne. In fact, Meunier is suited for soils that contain more clay and in terroirs with harsher climatic conditions since it buds late and makes it more resistant to frost. Sandwiched between the powerhouse wine regions Côte des Blancs and Vallée de la Marne, the Coteaux has an identity removed from either one; its terroir is distinctly different from the clay-heavy soils of the Marne and lacks the chalk of that puts the ‘blanc’ in the Côte des Blancs.

Phrasing it succinctly is Laherte Frères proprietor Aurélien Laherte: “Our wines show more clay influence than those of the Côte des Blancs and they are chalkier than the wines of the Vallée de la Marne.”

In short, these Champagnes are uniquely situated to offer the best of both worlds. As a result, the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay has long fought for recognition as entity unto itself, not necessarily a sub-region of its big brothers on either side.

Champagne Laherte Frères

Terroir Fundamentals: Preserving Its Details

That Champagne is, above all, a style of wine should be obvious, but a common misinterpretation (fueled in part by tradition and in part by marketing) removes it from viniculture and places it on a pedestal of the imagination. Nothing wrong with this, of course, so long as the ground floor remains intact.

Aurélien Laherte, along with his high school friend Raphael Bérèche, would like to see these ideas put into context. A group of Champagne’s more progressive producers, including Agrapart, Marie-Courtin, Vincent Laval and Benoît Lahaye, gathers each spring to taste the ‘vins clairs’—wines meant to become Champagne, but having not yet undergone the bubble-creation process. These are not necessarily ‘still wines’ in that they are not meant to stand on their own merits, but have terroir-transparency profiles to make them suitable for top-shelf sparkling versions.

The Laherte stamp-of-approval was placed on Champagne’s brow many years ago: Founded in 1889 by Jean-Baptiste Laherte, the estate was originally made up of vines grown in and about the village of Chavot. With his wife Cécile, fourth-generation vigneron Michel Laherte expanded the holding, modernized the press and tanks, and may be credited with realizing that the use of herbicides and pesticides prevents full terroir-expression in the wines. The philosophy of hand-working the soils, gently vinifying the juices, and remaining humble and patient as the wines develops became the foundational theme of the estate and endures to this day.

Situated largely in the Côteaux Sud D’Épernay, Laherte vineyards themselves total 26 acres subdivided into 75 separate parcels. Seven of these are farmed biodynamically and certified organic, with the rest farmed either ‘uncertified organic’ or sustainably. Each produces detailed wines that the estate seeks to showcase individually.

Aurélien Laherte, Champagne Laherte Frères

Aurélien Laherte took over in 2005 and is today considered to be one of the most dynamic vignerons in the appellation. From the multiple individual parcels, the estate produces a series of tiny production, single-vineyard, single-vintage cuvées (around 3,000 bottles each) from some of their most unique and expressive biodynamically-farmed parcels. Many of these wines are fermented and aged in used Burgundy barrels, without malolactic, and are bottled without fining and filtration. They are then finished with little or no dosage so as to not mask the individuality of the underlying terroirs.

Aurélien and his parents are registered as a négociant all the fruit grown by an extended family can be incorporated into his blends. “This is,” says, “the best way to contend with complicated French inheritance laws and keep the estate whole.”

The team, Aurélien upper left

Great lengths are taken to ensure each vine fully expresses itself and its underlying terroir. A team of ten, including aunts, uncles, and cousins, works throughout the year (in accordance with the lunar calendar) to employ techniques such as plant infusions to improve the vine’s natural defense system, and high foliage to encourage photosynthesis and thus, balanced maturity.

Village Chavot: Diversity of Soil

The commune of Chavot-Courcourt consists of Chavot (in the northeastern part of the commune) and Courcourt (in the central part of the commune), but also the small villages Ferme du Jard, Les Fleuries, La Grange au Bois, and Le Pont de Bois. Among the many folds and hills in the area, the upper reaches are clay-dominant while the soils turn chalkier as you descend. Most of the vineyards in Chavot-Courcourt are located in the northern part of the commune, on slopes formed by the stream Le Cubry.

Aurélien Laherte explains why he farms so many individual parcels in a relatively small area: “Below the village especially is a significant difference in soil types. I have identified 27 terroir-types in Chavot-Courcourt alone and farm 45 parcels. There is no sand, but there is virtually everything else—from chalk to clay to limestone. Between them are countless fine-grained distinctions, so I treat them individually and vinify them separately.”

Les Beaudiers is a vineyard in Chavot where Laherte Frères has old vines of Meunier (planted in 1953, 1958, and 1965) that are used for a rosé saignée. Other vineyard sites in Chavot-Courcourt include Les Charmées, Les Chemins d’Epernay, Les Monts Bougies, Les Noelles, La Potote, and Les Rouges Maison, all used by Laherte Frères for their Champagnes Les Vignes d’Autrefois and Les Empreintes.

Although Meunier is the dominant grape variety, Laherte also owns a vineyard called ‘Les Clos’ where he plants all seven legally allowable Champagne grape varieties. From this he concocts the individual-vinification philosophy by picking and pressing all seven varieties together.

Single Variety (Monocépage): Burgundy Comes to Champagne

Bordeaux, and indeed much of Champagne, blends grape varieties to create signature ‘house’ wines. In Burgundy, the thinking is different: Burgundies are primarily monocépages, meaning they are made from a single grape variety, often sourced from a single vineyard. In Bordeaux, the monocépage concept is virtually unknown, but in Champagne, most prominent producers will offer at least one or two in their portfolio, Blanc de Noir or Blanc de Blanc. Frequently they are vintage cuvée produced only in years where a special set of conditions are met and only released in limited quantities.

• Blanc de Blancs

Blanc de Blancs—a term found only in Champagne—used to refer to Champagne produced entirely from white grapes, most commonly Chardonnay. Pinot Blanc and Arbanne can also be used, as well as a number of other varieties permitted in the appellation, but these are much less common.

Chardonnay – ‘Emblematic Cuvée’

In Chardonnay Muscaté this mutation of Chardonnay is a genuine thing; it is grown somewhat extensively in New York state and Ontario under the name Chardonnay Musque and shows an exotic flavor profile that includes tropical fruit notes and cinnamon-tinged lemon sorbet.

Champagne Laherte Frères, nv Chavot & Épernay ‘Blanc de Blancs’ Brut-Nature ($53)

Champagne Laherte Frères, nv Chavot & Épernay ‘Blanc de Blancs’ Brut-Nature ($53)

From the chalkiest soils on the south slopes of Épernay and the Côte des Blancs, where Chardonnay vines average 35 years, Laherte hand-picks the grapes and ferments the juice in small foudres and barrels, relying on few bâtonnages. It is assembled using 50% reserve wines from previous vintages aged in barrels on lees; hence, the non-vintage label. Malolactic fermentation is partial and disgorgement is done by hand, without dosage. As a ‘non-dosé’, the wine is filled with shivery acidity, showing citrus and apple peel with accents of ginger and finishing with crushed rock minerality. Disgorged February 2022.

*click on photo for more info

Petit Meslier – ‘Vibrant and Expressive’

Petit Meslier is a somewhat rare white-wine grape grown in small quantities in Champagne. It is noted for its heat resistance and ability to maintain acids during long spells of hot weather and when vinified as a monocépage, provides tremendous aromatic intensity and depth.

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Petit Meslier’, nv Chavot Extra-Brut ($120)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Petit Meslier’, nv Chavot Extra-Brut ($120)

In creating his iconic, all-inclusive blend ‘Les 7’, Aurélien was particularly struck by the ability of his Petit Meslier to stand on its own. From a vineyard called ‘Cépages Oubliés’, it is blended with 40% reserve wine and aged for six months on its lees ‘fût de chêne’, or in oak barrels; it shows honeyed pear, buttered toast and toasted almonds behind an unsurprisingly racy spine of acidity. Disgorged December 2021.

• Blanc de Noirs

In Champagne, Blanc de Noirs mean that the wine is made from either Pinot Noir or Meunier (or a blend of the two), although it’s relatively common to find 100% Pinot Noir. Despite the ‘Noir’, they may be notably ‘Blanc’ since both Pinot Noir and Meunier are red-skinned, white-fleshed grapes that produce clear juice. Without being given time to macerate on the dark skins, the wine will be white.

Pinot Noir – ‘Intense and Straight’

Pinot Noir accounts for 38% of the area under vine in Champagne and is the dominant grape in Montagne de Reims and Côte des Bar. It is frequently referred to as ‘Précoce’ due to its tendency to ripen early, leaving behind the acidity so prized by Champagne makers. It thrives in cool, chalky soil—a hallmark of Champagne’s terroir.

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Longue Voyes’, 2018 Montagne de Reims (Premier Cru Chamery) Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut ($83)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Longue Voyes’, 2018 Montagne de Reims (Premier Cru Chamery) Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut ($83)

Part of Aurélien Laherte’s’ Terroirs’ series, this is his first Blanc de Noirs Champagne made entirely from Pinot Noir. The fruit comes from the village of Chamery on the Petite Montagne de Reims, nearly twenty miles from the estate—hence the name, which means ‘The Long Way’. Barrel aged for 18 months with a 4 g/l dosage and no malolactic, the nose reveals notes of black fruits, and the palate is lively, tense, tasty and tonic with a persistent saline finish. Disgorged December 2021.

*click on photo for more info

Meunier – ‘Celebrating the Variety’

Traditionally used as a blending grape, there are about 26,000 acres of Meunier planted in Champagne, and the variety is rapidly becoming more than an afterthought used for color and balance. In the right soil conditions (calcareous clay with deeper chalk layers) and if allowed to ripen well (leapfrogging the vegetal stage) it can produce a wine that ages remarkably, showing finesse and freshness even after years in the bottle.

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Vignes d’Autrefois’, 2018 Chavot & Mancy Extra-Brut ($83)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Vignes d’Autrefois’, 2018 Chavot & Mancy Extra-Brut ($83)

The selected Meunier plots for this wine were planted by the Laherte family between 1947 and 1953 in the villages of Chavot (lieux-dits La Potote and Les Rouges Maisons) and Mancy (lieu-dit Les Hautes Norgeailles). Some of the vines were planted on French rootstock while others are the result of old massal selection. Aurélien uses traditional wooden Coquard presses; fermentation occurs with native yeast in old Burgundy barrels and malolactic fermentation does not take place. The wine ages up to 19 months on the lees and dosage is between two and four grams per liter; it exhibits marvelous aromas of white peach, violets and verbena. Disgorged November 2021.

*click on photo for more info

• Rosé

Credit Madame Clicquot for revolutionizing the (then) relatively small production of pink Champagne. A believer in the idea that a wine should flatter both the eye and the palate, the Grande Dame broke with tradition and re-created the process of making rosé champagne. Before, it was made by adding an elderberry-based mixture to white champagne, but Madame Clicquot had had vines in the Bouzy region of Champagne where she made her own red wine, and she decided to blend this with her still white wines.

This is the most common method of producing rosé Champagne—blending clear white and black grape musts, using between 5 and 15% red wine; it is called a rosé of ‘assembly’. The proportion of red wine can vary, but the white wine must be the majority. Another method of rosé production is the ‘saignée’ method, which involves allowing the must to undergo minimal skin contact, generally for only a couple of hours. This minimal maceration allows the must to develop stronger aromas and flavor profiles while deepening the color. ‘Saignée’ translates literally to ‘bleeding’, which is essentially what the skins are doing for the juice.

Meunier – ‘Strong Identity’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Rosé de Meunier’, nv Chavot & Vallée de la Marne (Le Breuil & Boursault) Extra-Brut Rosé d’Assemblage ($54)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Rosé de Meunier’, nv Chavot & Vallée de la Marne (Le Breuil & Boursault) Extra-Brut Rosé d’Assemblage ($54)

100% Meunier, the wine is sourced from vineyards with an average age of 25 years for the Meunier vinified white and more than 40 years for the parcels selected for the red wine. It is a blend of 30% macerated Meunier, 60% white wine from Meunier and 10% still red Meunier. As a result, it uses both methods of Champagne rosé creation, assemblage (blending) and saignée (bleeding). The wine is multi-layered with a ripe core of red fruit and brisk girdling acids. Disgorged March 2022.

*click on photo for more info

Meunier – ‘Varietal Complexity and Nuances’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Beaudiers’, nv Chavot Extra-Brut Rosé de Saignée ($83)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Beaudiers’, nv Chavot Extra-Brut Rosé de Saignée ($83)

100% Meunier from the ‘Les Beaudiers’ lieu-dit, planted in 1953, 1958 and 1965 on shallow clay and silty soil with chalk beneath. As always, Laherte’s methods include organic maintenance, short pruning for a limited production and regular ploughing. Fermentation takes place in old Burgundy barrels and hand-disgorgement with 0 to 4.5 g/l. The wine shows creamy red cherries, kirsch, buttered toast with strawberry jam and a bright, flinty spine. Disgorged November 2021.

*click on photo for more info

Blending: A Tapestry of Few Threads

Champagne should illustrate the word ‘synergy’ above all, where the sum of the total is greater than the individual parts. The ideal blend should be the aggregation of positive components; every thread should add to the tapestry’s whole. The blend should always drive toward harmony; Chardonnay is often up front, while Pinot Noir supplies the middle and finish. Other allowable varietals should only appear if they contribute to the primary blend.

This is not a universal outcome, of course, and according to Jean-Marc Lallier of Champagne Deutz, “Some winemakers do not blend; they mix.”

When cellar masters do it right, it is a painstaking undertaking; every tank, barrel and vat is tasted countless times to assess which batch would enhance which. This is the true art of Champagne making—the intimate familiarity with each component in order to align them perfectly.

At Laherte, Aurélien does not have a recipe for a single wine; he blends according to the call from the barrel and each blend has a trademark distinction. He prefers very low dosage, insisting that the wine’s minerality must speak first. Regarding the tedious art of blending, he says, “They’re like people; one needs to be strong, one of them weak; one bitter, one elegant.”

‘Highlighting Chavot’s Terroir’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Empreintes’, 2016 Chavot Extra-Brut ($87)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Empreintes’, 2016 Chavot Extra-Brut ($87)

From two parcels in the Chavot lieux-dits Les Chemins d’Épernay and Les Rouges Maisons, each (in Aurélien’s words) ‘exemplifying the quintessence of the Chavot terroir.’ The wine is a classic Champagne blend, half Chardonnay, (of which one-third is Chardonnay Muscaté) from Les Chemins d’Epernay where there are clay soils with a little silt stratum in surface and a chalky subsoil—vines planted in 1957. The other half is Pinot Noir from Les Rouges Maison where the soil is fairly deep with a vital presence of clay, flints and schists; these vines were planted in 1983. With a dosage of 3.5 g/l, it is a resonant Champagne with floral top notes and deftly balanced acidity. Disgorged January 2021.

*click on photo for more info

‘Return to Basics’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Ultradition’, nv Extra-Brut ($48)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Ultradition’, nv Extra-Brut ($48)

60% Meunier, 30% Chardonnay, 10% Pinot Noir from vineyard plots in the Côteaux Sud d’Épernay, Vallée de la Marne and Côte des Blancs where vines average around 30 years. The wine ages in barrels for six months and given light filtration before bottling during the spring time; 6-8 gr/l dosage. The wine offers a complex bouquet of dried apple and toasted walnut; the Meunier lends floral tones and an upper-register smokiness. Disgorged November 2021.

*click on photo for more info

‘Tribute to Yesterday’s Wines’

The system of maturation used for Sherry, the famous fortified wine of Jerez, is a cry for consistency from vintage to vintage. The soléra (or perpetual cuvée) system involves removing wine for release from the last of a series of barrels that contains a blend of every vintage since the solera was started. The void in those barrels is then filled with wine from another series of barrels, and so on, until there is room in the youngest series of barrels. The wine from the most recent vintage is added to those barrels.

In Champagne, the method used is slightly different; after each harvest, wine is added to the blend, and every time a producer is ready to release a new batch of non-vintage Champagne, he/she removes what he/she needs. Over time, the cuvée becomes increasingly complex as the fresh wines of the latest vintage taking on the mature qualities of those that came before it. It is a system used by surprisingly few producers in Champagne, but Laherte Frères is one of them.

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les 7’ Soléra 2005 to 2018, nv Chavot Extra-Brut ($120)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les 7’ Soléra 2005 to 2018, nv Chavot Extra-Brut ($120)

As the name suggests, all seven allowable Champagne grapes are used in this single cuvée; 10% Fromenteau,18% Chardonnay, 18% Meunier, 15% Petit Meslier, 8% Arbanne, 14% Pinot Noir and 17% Pinot Blanc from a vineyard planted by Thierry Laherte in 2003. He picks and presses all seven together and employs his perpetual cuvée: ‘Les 7’ contains wine not only from the current vintage, but draws bits of reserve wine from all harvests dating back to 2005, the year Aurélien took over the domain. All bottles are disgorged by hand with a dosage of 3 g/l. The wine shows lemon zest, crystalline green-apple candy and floral notes in a stony infrastructure. Disgorged January 2021.

*click on photo for more info

- - -

Posted on in France, Saturday Sips Wines, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

An Economy Tour of the Northern Rhône: Ambitious Appellations Capture Syrah’s Flavors and Emotions in Open and Easy-Going Manners (7-Bottle Sampler $249) + Saturday Sips

Join Us for Saturday Sips

Come as you are; come any time that’s convenient for you during our business hours to sample selection from this week’s selections. Our staff will be on hand to discuss nuances of the wines, the terroirs reflected, and the producers.

The price of a barrel of crude oil rises and falls on political whims, but the price of fine wine seems locked into an upward trajectory. Take that truism to the bank and take the bottle to the vault. It’s one of the reasons people invest in wine, especially in excellent vintages from top houses. But this is not to suggest that reliable bargains cannot be found in large, ambitious appellations set in ideal climates where certain noble varieties flourish … like Syrah.

As a varietal, Syrah wears many faces and goes by several names; Shiraz is the most common, of course, and is the one preferred by the New World. But Syrah may also be disguised as Balsamina, Candive, Entournerein or Hignin Noir. As varied as the names is the grape’s profile—floral in youth and then developing white and black pepper aromas and herbaceous notes as it ages. The fruit tends towards the dark flavors of blackcurrant and the spice toward licorice and cola.

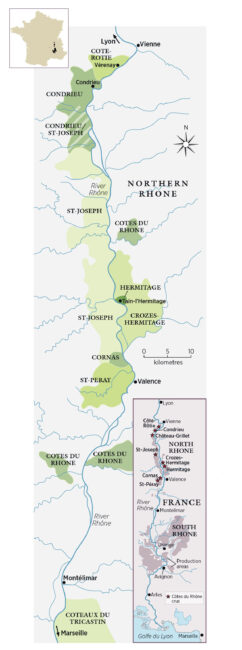

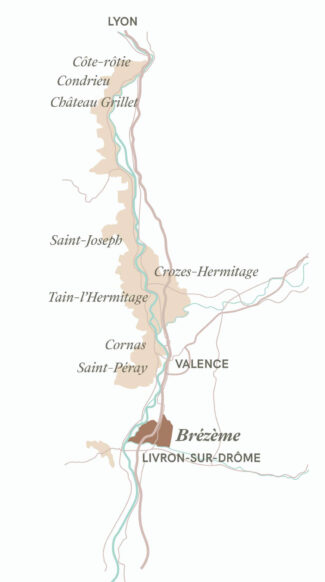

Northern Rhône is the fountain from which the most spectacular Syrahs spring, especially in the Côte-Rôtie, Hermitage, Cornas, Crozes-Hermitage and Saint-Joseph appellations, where the earthy, savory style can improve for many years inside the bottle. The granite slopes on which the vineyards of Northern Rhône are planted can be brutal in growers—some are so steep that pulley systems are used for grapes and equipment. Techniques like these add substantial costs to wine production, so when you see a reasonable price affixed to a bottle from Northern Rhône, be assured that the profit margin for the winemaker is probably less than a gluggable Shiraz grown on a flat plateau in Adelaide’s Riverland.

This week’s package contains examples of Northern Rhône wines that strike the ideal balance sought by people who consume rather than collect—smoky complexity, Syrah typicity, and lovely drinkability and at a price that will not require a second mortgage.

Northern Rhône Royalty: Côte-Rotie, Cornas and Hermitage

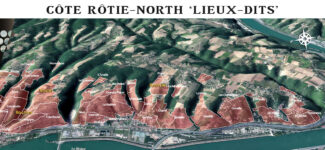

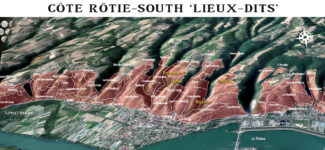

The triumvirate of Côte-Rôtie, Cornas and Hermitage rule the narrow terraces of Northern Rhône indomitably and are responsible for the world’s most superlative Syrahs. They’ve been called ‘unicorn wines’ in that the best of them are rare, and if available, very expensive.

Rolling above the town of Ampuis, the roasted slopes of Côte-Rôtie have several distinct personalities, one most suitable for wine, the others, less so. Only the south and south-east facing hillsides on right bank of the river are worth the discomfort of cultivating and picking, while those to the south—collectively known as the Côte Blonde—produce similar but earlier drinking wines than those produced on the Côte Brune to the north (although traditionally, the wines from these areas have been blended).

One of the smallest appellations in Rhône, Cornas is under three hundred acres—smaller than some single estates in Bordeaux. It produces only red wines made exclusively from Syrah—a variety that ripens with greater ease here than virtually anywhere else in Northern Rhône. Celtic for ‘burnt earth’, Cornas wines—in homage to the name or vice versa—frequently reflects smoky notes with deep, burly earth tones. Once considered ‘country wines’ of value only to those who love rusticity, the reputation of Cornas has skyrocketed in recent vintages to become one of the most sought after wines in France.

From a handful of vineyards, Hermitage is responsible for some of France’s most enduringly prestigious wines, in part by allowing the addition of 20% Viognier to its Syrah. Whether white or red, these gems are long-lived and full-bodied. Terroir, of course, is lifeblood: The granite hillside where the Hermitage vineyards are planted face south, overlooking a short section where the river Rhône flows west to east rather than north to south. This orientation means that the grapes benefit from the maximum amount of sunlight throughout the day.

The Sleeping Beauties of the Northern Rhône

A number of smaller, previously dormant areas that nestle in pockets near the big-name appellations in the Rhône have begun a remarkable comeback; this is the result of hard work by few steadfast vignerons who have saved noteworthy properties from being reclaimed by forest. It is among these parcels of land, which peek through mostly unfriendly hinterland that we make our modern-day discoveries— worthy and exciting Syrahs; the best made since the phylloxera blight wiped out the original vineyards in the 1800s.

Domaine Les 4 Vents

Formerly Le Domaine de Lucie, the 25-acre domain was renamed when Nancy Cellier joined her sister Lucie Fourel at the helm of the family estate in Crozes-Hermitage. The new name was borrowed from the nearby auberge (country inn) once owned by Lucie and Nancy’s great grandparents.

Sisters Nancy and Lucie Fourel, Domaine les 4 Vents

Before returning to the estate, Lucie spent a few years as an apprentice with different wineries in the Rhône Valley—time she spent developing both the philosophy and practices for bio-dynamic farming and natural vinification for which the domain has obtained certification. Lucie does not use sulfur during the winemaking process and only just before bottling does she add a minimal dose and the wines are fermented using only indigenous yeasts.

“We are in perpetual search of respecting the environment,” says Lucie. “Our interventions in the vineyard or in the cellar aim to accompany the grapes, then the wine, towards its most authentic expression”.

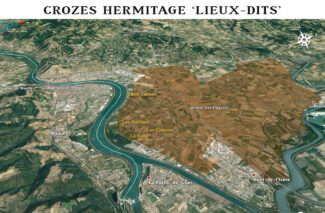

Crozes-Hermitage

Crozes-Hermitage is the largest of the Northern Rhône appellations, but it labors in the shadow of its storied namesake Hermitage without pretentions of equality. Price reflects that, of course, and the wine itself does hold at least some measure of the magnificence found in its massive, long-lived neighbor. The wine-growing region has a continental climate distinct from the Southern Rhône, and its sheer size adds to the diversity of its terroir. Soils south and southwest toward Gervans largely consisting of granite and clay, while Tain-l’Hermitage is primarily made up of rocks, sand, and clay. The flatter topography in the southern Crozes-Hermitage area is primarily alluvial soil due to Rhône river deposits.

Domaine Les 4 Vents ‘Les Pitchounettes’, 2020 Crozes-Hermitage Rouge ($28)

Domaine Les 4 Vents ‘Les Pitchounettes’, 2020 Crozes-Hermitage Rouge ($28)

‘Les Pitchounettes” is a cuvée that originates from relatively young vines in the lieu-dit Les Chassis near the village of Mercurol where the soil is a sandy-silty alluvial clay with a lot of surface river stones. Yields are very low, typically around 30 hectoliters per hectare and harvesting is done by hand. The grapes are de-stemmed and the juice is left to macerate with the skins for three weeks with very little rémontage or pigéage (pumping over or punching down the cap). The wine shows classic Syrah flavors of black fruit and smoky pepper accented by cedar, vanilla and tobacco.

Domaine Eric et Joël Durand