The Future of Burgundy Lies in Lesser-Known Areas: To Mitigate Climate Change, Boris Champy Is Convinced Higher Elevation and Vineyrad Orientation Hold Some of The Answers. (4-Bottle Pack $259)

“The best fertilizer is the winemaker’s shadow.”

Nowhere does this aphorism hold truer than in Nantoux, Burgundy, where Boris Champy carries on an endless quest to reveal the soul of each vineyard plot, the spirit of each grape variety and the essence of place inherent in every glass of wine. Having purchased the estate from Didier Montchovet—one of the biodynamic pioneers in France who were practicing eco-friendly, solidarity-driven viticulture before the word became fashionable—Champy took over with the intention of using global warming as an advantage in lesser-known mountainside vineyards.

This week’s 4-bottle sampler package reflects both the philosophy and the product: Stellar examples of Burgundy’s new visage. Boris Champy has awoken long overlooked terroirs to produce wines with cellar-aging potential as well as immediate enjoyment—a work-in-progress that Champy describes as being ‘the result of patience and foresight; a path that respects man in his environment.”

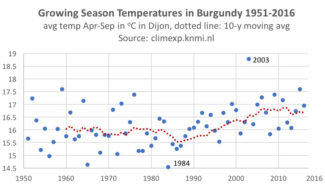

Burgundy’s Climate Change Challenge

April, 2021 has been called the worst month ever for French vineyards: Severe spring frosts created crop losses estimated at 80 to 90% in some areas. These chilly announcements from the planet at large are but a single symptom among the host of challenges that climate change is bringing to the region.

Burgundy’s reputation for elegant wines is inextricably linked to its cool northerly climate. When summer temperatures remain consistently above normal, grapes ripen more rapidly and are at risk of losing the delicacy that translates into finesse when vinified, and although there is certainly a place for bigger, fatter, bolder Chardonnays and Pinot Noirs, this market has been saturated in the past few decades with wine from warmer, flatter regions in the New World, and, in fact, bucks current consumer trends.

Burgundy’s winemakers are not without options, of course, having at their fingertips an array of viticultural and winemaking tools to mitigate the damage. But as 2021’s frost proves, such methods are not fool-proof and more drastic action will likely follow, from restructuring the Cru system to exploring the potential of other grape varieties. Burgundy has placed nearly all of its varietal eggs in two baskets, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, and upsetting this particular apple cart is not an easy decision for an area tied to tradition. But along with finding new terroirs in regions previously unsuited for viticulture—higher elevations, for example—they may represent not merely the best routes, but the only ones.

2020 Vintage: Earliest Harvest Since 1556

The term ‘ban des vendanges’ may not be familiar outside Beaune, but it represents the earliest date on which harvests have been allowed to start. Pick earlier and you might forfeit your entire crop—‘ban des vendanges’ was a form of quality control that ensured the grapes were not harvested unripe. After 2006, following the ‘ban’ was no longer mandatory became a symbolic date, set much earlier than is practical for harvesting. Historically, this date has been a consensus between vine-growers and local town administrators and also considers the availability of harvest labor coming from outside of the town and even the potential for military threats or outbreaks of plague.

And with Covid in full swing, that sounds like 2020, when the harvest began on August 14, fully two days earlier than the record set in 1556, August 16.

Domaine Boris Champy

An Eco-conscious Producer on Higher Grounds

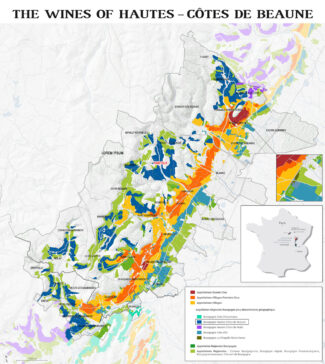

Boris Champy is to the Hautes-Côtes what ‘imagineers’ are to Disney—seers of the future. With the steady march of global warming, Champy recognizes that mountain vineyards will become more temperate in the decades ahead, and his vineyards are well suited to raise the reputation of the entire appellation. With more consistent ripening, Champy’s objective is simple: To show the subtle differences between the climats and terroirs to which he has access via soil types, sun exposures and slope inclinations.

To this cornucopia of promise, Champy brings an organic mindset: “We practice a viticulture respecting nature. Our single plot vineyards are large biodiversity islets where a holistic approach is required; a global ecosystem with regenerative farming and utter respect for the environment.”

Boris Champy – Domaine Boris Champy

Champy began his oenology career on near-hallowed Napa ground, remaining with the Dominus Estate for a decade. He later became technical director for a well-known négociant in Beaune, and then estate manager for the famous Clos des Lambrays in Morey-Saint-Denis. He was also president of the Corton ODG and responsible for the creation of an environmental protection association.

“My goal from the beginning has been to showcase the lieux-dits of the high-lying hills and valleys of the Hautes-Côtes, and to highlight the different microclimates, exposures and other fascinating subtleties,” Champy says. “As a means to this end we practice viticulture that is still somewhat alien to the great winegrowing Côte. Our vineyard plots are small islands of biodiversity with numerous quickset hedges, meurgers (thick stone walls) and fruit trees. This is a philosophy of regenerative agriculture.”

Regenerative Agriculture: Broader View of Viticulture and Sustainability

In recent years, the term ‘regenerative agriculture’ has replaced ‘sustainable’ in the lexicon of ecology, at least as a consummation more devoutly to be wished. Sustainable farming is a harm-reduction approach—a crucial first step on the path toward creating an overall system that actually adds to nature’s richness. A farmer can begin by reducing external inputs like pesticides, for example, and eventually enhance the health of the land so much that chemicals aren’t needed at all. When measures to enrich the land—such as planting shade trees to protect and nourish soils—are applied on all fronts, you may lay claim to being a regenerative farm.

Boris Champy is a cheerleader for this method: “At the domain we believe entirely in this concept of agriculture: Our hedges are a habitat and a source of food for wildlife. Birds will feed on the seeds of plants growing amid the vines. Birds of prey will feed on small birds and mammals. Hazel trees, brambles and hawthorns have a positive impact on the soil. Mycorrhizae, fungus networks and other microorganisms will help build the strength of the vines that in turn will be transmitted to our grapes.”

Animals and non-vine flora are his partners in the approach, and he points to hedges and thickets with thick dry-stone walls that provide a perfect habitat for birds, lizards and fertile ground for orchids. “We showcase the domain’s history in the plants we encourage; black pines, Scots pines, sorb trees. Each of these trees bears witness to our domain’s past: wood from the sorb tree was used to make the screw of the wine presses; the black pine was planted after Phylloxera. We also allow dead trees to decompose to encourage biodiversity.”

Biodiversity: a Garden, a Dog, Sheep… and Chicken

The age-old farming paradigm, still prevalent, is changing: Time was, agricultural wisdom called for one or two species of forages and grazed by a single species. In France, as in the Midwest of the United States, this is generally what you still see: Closely grazed pasture with leggy tufts of mature stalks from less-palatable plants bringing selection pressure to bear in causing the eventual demise of the best forages.

Boris Champy and Napa – Domaine Boris Champy

Boris is a trendsetter: “We like to use the green manuring technique: in summer we sow vetch, rye, fava beans, mustard, Chinese radish and peas between the rows. These plants offer many benefits: they improve soil fertility, provide nitrogen and support microbial life. They are also bee-friendly, to the delight of the local beekeeper! We are bringing grazing back into fashion with a flock of sheep that gives our vineyards a thorough natural mowing. Our flock is made up of Thone and Marthod sheep, a breed from the Alps, which is very docile and accustomed to our Border collie, named ‘Napa’. Napa is very useful on the farm, especially for rounding up the sheep and moving them from one plot to another during the grazing periods. Thanks to our friend Fred Ménager from the Ferme de la Ruchotte, we have also adopted some specimens of old breeds of hen: Gauloises Dorées, Gauloises Grises, Faverolles, Le Mans and Marans.”

The Awakening of Terroir Through Natural Viticulture and Winemaking

Boris Champy thinks about the past nearly as much he considers the future. He says, “Over my career, I have had the opportunity to participate in exceptional vertical tastings of Côte de Beaune and Côte de Nuits wines. Each time, I have come to the same conclusion, that authentic wines from the years 1910 to 1950 have stood the test of time. They are excellent wines with fruit and complexity which are still a pleasure to drink. From the 1960s onwards, the quality becomes inconsistent, the wines are often dull, boring or sometimes dead due to intensive viticulture (chemical fertilizers, weed killers, synthetic chemistry, clonal selection, etc.). From the 1990s onwards, the quality of the wines returns. Some have called this the ‘awakening of the terroirs.’ Our decision to use natural viticulture and winemaking has the single but ambitious objective of producing wines with cellar-aging potential that have taste and are enjoyable to drink.”

The Pinot Fin and The Use of Whole Bunches

In another nod to history, Boris Champy explains his passion for using a high proportion of whole bunches of grapes by reminding us how recently the destemmer machine came to the wine cellar. “Like every invention,” he says, “it has both positives and negatives. Destemming has led to higher yields (with grapes that are not necessarily very ripe), and the planting of certain clones that produce large bunches of grapes whose stalks are unable to ripen. The return to the use of whole bunches is a rejection of these industrial techniques: viticulture with lower yields, the abandonment of high-production clones, the pursuit of perfect maturity and vinification by plot.”

This, he believes, is borne out by tasting and analyzing old vintages. “When we consider very old wines, and specifically, certain tannins derived from the stalks, we can conclude that, in the 1910s and 1920s, the very great Burgundy wines were made from whole bunches of grapes. We are still learning about these stalk tannins: They have a ‘sweet’ taste, a characteristic typicity that can be found in the very great wines produced today using whole bunches by the world’s greatest estates (DRC, Leroy, Dujac, Gonon, Chave, etc.).”

The Hautes-Côtes Area

Beaune’s High Coast for Pinot Noir and Chardonnay

Before the phylloxera plague of the nineteenth century, vines grown on the sunny, limestone cliffs along a ribbon of valleys perpendicular to the Côte de Beaune from Les Maranges to Ladoix-Serrigny were a famous source for Chardonnay and Pinot Noir; these were the wines that were ordered to celebrate the coronation of Philippe Auguste in 1180. Post-phylloxera, between 1910 and 1936, almost half of the Hautes-Côtes de Beaune vineyard disappeared.

The region’s renaissance began with reestablishment of the winegrowers union of the Hautes Côtes de Beaune in 1945, which led to the creation of the appellation on 4 August 1961. The terroir is largely built around formations laid down 80 million years ago during the Triassic (sandstone and clay) and the Jurassic (marl and limestone) eras. The favored sites are on south and southeast-facing slopes of valleys cut into the limestone plateaus at between 900 and 1500 feet; considerably higher than the Côte de Beaune, which results in later maturing grapes and harvesting, on average, around one week later.

Boris Champy labels his wines according to the elevation of the vineyards; hence, Cloud 377 indicates, in meters, how high up the slope this plot of grapes grows.

Domaine Boris Champy ‘Clou 377’, 2020 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Beaune Red ($63)

Domaine Boris Champy ‘Clou 377’, 2020 Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Beaune Red ($63)

Au Clou is plot of Pinot Noir that sits at 377 meters altitude (1237 feet) where the soils are white and stony with a high marl content—similar to the terroir of Châteauneuf-du-Pape. The vines are planted in traditional high-density style, with 10,000 vines/ha using Guyot cane pruning. Grapes are hand-harvested at optimum ripeness and vinified using soft extraction with a large proportion of whole clusters used in wooden fermenters, followed by barrel aging for one year using an average of 30% new oak. The wine is perfumed with raspberries and violets, with silky black and red berries on the palate peppered with black tea and allspice.

Domaine Boris Champy ‘Montagne 388’, Bourgogne 2020 Hautes-Côtes de Beaune White ($53)

Domaine Boris Champy ‘Montagne 388’, Bourgogne 2020 Hautes-Côtes de Beaune White ($53)

388 meters = 1273 feet; Montagne de Cras is a 10-acre lieu-dit made up of vines abutting natural areas of biodiversity; scree slopes, hedges, orchards, limestone grasslands with numerous orchids and even a few rare corm trees, whose wood was once used to make screws for grape presses. Vinification takes place in 228-liter oak barrels (15% new) and, in part, in small round stainless-steel vats. This 100% Chardonnay is the antithesis of fat, oaky Chardonnays, showcasing instead a racy and bright style with lovely aromas of lemon, almond, stone, spiced pear and apple.

Bourgogne Aligoté

Burgundy’s Other White Grape Aims High

“Aligoté!” sounds like a cry of triumph; something you’d shout after making a goal in the World Cup. In fact, perennially overshadowed by its sexier cousin Chardonnay and even its half-sister Pinot Gris (they share a father, Pinot Noir), there was a time when the opposite was true:

“Before phylloxera,” says Jérôme Castagnier, proprietor of Domaine Castagnier in Morey-Saint-Denis, “Aligoté was planted everywhere, literally. But after the outbreak abated, thanks primarily to American root stock, French growers took stock and realized that Chardonnay and Pinot Noir commanded higher market prices, so that’s what was re-planted. In fact, in some regions, Aligoté was banned altogether.”

Post-phylloxera Aligoté exists under the basic Bourgogne Aligoté appellation established in 1937 and, for the most part, produces inexpensive and simple wines, especially when planted in the less-valued soils of the Saône Valley flatlands. But true Aligoté fans, including Les Aligoteurs (a group of French producers and wine lovers who promote Burgundy’s all-but-forgotten white grape variety) believe that the grape better expresses the terroir of thinner, rockier, hillside soils. A cross between Pinot Noir and the ancient white varietal Gouais Blanc, Aligoté’s profile includes descriptors ranging from fruit-driven and floral to herbal and sharp with acidity. In either case, it is the essential base for the classic cocktail Kir when blended with Cassis.

2020 Domaine Boris Champy ‘Sélection Massale 429’, 2020 Bourgogne Aligoté Doré ($36)

2020 Domaine Boris Champy ‘Sélection Massale 429’, 2020 Bourgogne Aligoté Doré ($36)

429 meters = 1060 feet. The fruit for Aligoté Doré—‘Aligoté Gold,’ an Aligoté clone Champy replanted with cuttings from his best vines—comes from a blend of plots grown above the 400 meter mark where the soil is marl, clay and limestone bedrock. The vines are very old, and not very productive, so the fruit displays mature concentration with complex aromas of citrus fruits, peach, and fresh bread. The palate is balanced and vibrant with a finish that is elegant, full, and nuanced. Neutral oak aging adds texture and depth.

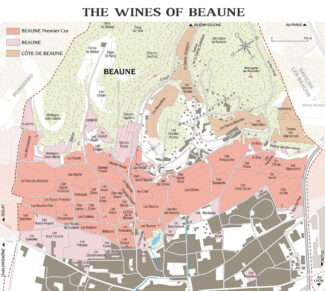

The Côte Area

A Premier Cru Facing Southwest

‘Coucherias’ is a Premier Cru vineyard located on a steep southwest-facing section that has magnificent views of the sunset—‘Coucherias’ is a name that references the setting sun. These are old vines planted in 1964 and cultivated using biodynamics since 1985. The plot is situated on clay and limestone, divided into two sub-islets, the smallest being a former quarry. The soil is very clayey and red, which gives a dense texture to this wine’s tannins. The Clos itself is isolated by trees and broom, which is a rare plant in Burgundy.

Domaine Boris Champy ‘272’, 2020 Beaune Premier Cru Aux Coucherias Red ($108)

Domaine Boris Champy ‘272’, 2020 Beaune Premier Cru Aux Coucherias Red ($108)

100% Pinot Noir, the wine expresses nettles and tea-leaf spice behind bright raspberry and tomato leaf, a whisper of wood and airy red currant notes.

- - -

Posted on 2023.08.30 in Côte de Beaune, France, Burgundy, Wine-Aid Packages

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Aglianico, Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Beaune, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Clairette, Corvina, Cot, Counoise, Erbamat, Ferrol, Fiano, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Fumin, Garnacha, Gewurztraminer, Godello, Graciano, Grenache, Grolleau, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Melon de Bourgogne, Merlot, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montepulciano, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscadelle, Muscat, Natural, Nero d'Avola, Parellada, Patrimonio, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Auxerrois, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Rondinella, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sangiovese, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Viognier, Viura, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- February 2004

Search