The Methodical Purist: Emmanuel Lassaigne (at Champagne Jacques Lassaigne) is Redefining Terroir in Champagne’s Outlying Sub-region Montgueux ‘Les Vignes de Montgueux’ $68 (Hint: Valentine)

The Methodists were named for a methodical approach to Christianity and the Puritans for a desire to purify it. Although Montgueux’s roots are a bit more pagan (the name means Hill of the Goths), Emmanuel Lassaigne’s angle of approach combines both philosophies, and in doing so, creates the region’s finest Champagne.

As an officially-delineated growing region, Montgueux—a mere fifteen minutes from Troyes—arrived late to the Champagne party; most of the current vines were planted in the 1960s. Among the first to reclaim Montgueux’s once-renowned terroir was Emmanuel Lassaigne’s father Jacques, from whom he took over Champagne Jacques Lassaigne in 1999.

As background notes to his latest project, a renowned two-acre Montgueux vineyard called Clos Saint-Sophie, Emmanuel says: “There were twenty varieties of grapes growing here in the 1880s. The Clos was so well known that Japanese botanists came to study it in 1886 and took a hundred cuttings back with them—the first Vinifera vines to grow in Japan.”

Join us on an exploration of this tiny chalk hill 60 miles south of Épernay, unlike anywhere else in Champagne, led by the tour guide who knows it best, Emmanuel Lassaigne. So in love with Montgueux is Lassaigne that he purchases up to 30% of his grapes from vineyards he does not own simply to present a more unified spectrum of the region’s remarkable terroir.

The Landscape of Champagne: Rethinking the Sub-regions

Classification is a man-made phenomenon; a way of understanding and categorizing a complicated world. Biologists do it, chemists do it, musicologists do it, but no field of study seems more joined at the hip to classification than oenology. Champagne, for example, has typically been subdivided into three major regions—the Montagne de Reims, the Côte des Blancs and the Vallée de la Marne. But, like the platypus who threw a curve ball to biologists as an egg-laying, duck-billed mammal, the classical subdivisions of Champagne ignore a portion of the 84,000 acres legally allowed to wear the Champagne label.

On the other end of the scale, the Comité Champagne (an umbrella organization for both growers and Champagne Houses first formed in 1898 to combat phylloxera) offers its own dizzying classification system, dividing the region in twenty individual sub-regions.

Finding neither taxonomy satisfactory, Champagne writer and former editor of ‘Wine & Spirits’ Peter Liem has found a middle, yet all-inclusive ground with seven named sub-regions—even while admitting that he is courting controversy.

Of the original three divisions, he leaves the Montagne de Reims and the Côte des Blancs intact, but argues that Vallée de la Marne should be broken in two to reflect the chalky bedrock of the northeast supporting primarily Pinot Noir and the collection of villages southwest of Épernay (called, unsurprisingly, the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay) where, within a relatively small region, a distinct variety of soils and terroirs can be found. The Côte des Bar is handed to us ‘as is’ since the principal vineyard area of the Aube lies on Kimmeridgian marl, much like its neighbor Chablis.

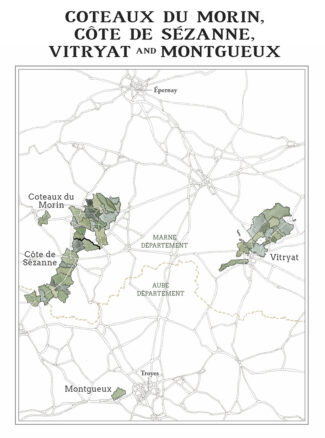

The most interesting sub-category in Liem’s system is the quartet of Côte de Sézanne, Coteaux du Morin, Vitryat and Montgueux. He groups them together despite their unique but isolated characteristics chiefly because they are areas of new plantings.

• The 1500 acre Côte de Sézanne sits a few miles southeast of Étoge in the Côte des Blancs. Chardonnay accounts for around 75% of the vineyard plantings, but there is a significant amount of Pinot Meunier and Pinot Noir. Sézanne wines are known for being among the fruit-forward in the region.

• Contiguous to the vineyards of Sézanne, the Coteaux de Morin forms the northern end of a string of vine-clad hills south of the Côte des Blancs. 2200 acres of vineyard comprise the region; about half is Pinot Meunier, 40% Chardonnay and the rest Pinot Noir.

• Vitryat is located in the Côte des Blancs but removed from the main by 25 miles (to the east); this is Chardonnay country, and this variety dominates Vitryat’s 1130 acres of limestone marl to produce elegant wines with a stony minerality unlike the crisper Champagnes that typifies the Côte des Blancs.

• Montgueux, the smallest of the four sub-regions, is made up of 514 acres of chalk, where the vines generally face south along a single hillside. These wines are renowned for their exotic fruit flavors, especially pineapple and mango. According to Emmanuel Lassaigne, “Our south-facing exposure always produces these tropical wines, but the soils are very chalky, so there is a lot of minerality too.”

Chalking Up Differences: Montgueux Rocks

In general, if you chalk up Champagne terroir to chalk, you are close, but like the grapes themselves, there are many flavors of this white, soft porous rock, made from the gradual accumulation of fossilized shells from marine life. The ‘Paris Basin’ is the key geological formation that produces the remarkable terroirs of northern France; a giant limestone bowl that, 75 million years ago, was a shallow sea where eukaryotic organisms lived, died and piled up. A slow tilting of this basin allowed the Seine, Aube, Yonne, and Loire rivers to cut through the rising ridges and form an archipelago of wine areas of which Champagne figures prominently, along with the Loire Valley and Burgundy.

The Campanian chalk that dominates the Côte des Blancs and the Côte de Sézanne is the standard-bearer for Champagne’s terroir, but the chalk in Montgueux and Vitryat, for example, is 13 million years older—deposits from the Turonian Stage.

Montgueux is an outcropping of pure Turonian chalk sitting three hundred feet above the surrounding plains, and although this soft limestone is the predominant mineral presence, small amounts of red clay and flint are also found in the soil—trace elements that allow Montgueux Chardonnay to express a full aromatic palate.

The Montrachet of Champagne: Chardonnay in Montgueux

“Explosively aromatic with notes of lemon peel, pomelo and passion fruit giving way to notes of gingerbread and toast.”

This could easily be mistaken for Montrachet tasting notes, but in fact, it is a description of Champagne from Clos Sainte-Sophie in Montgueux. Sainte-Sophie has a more easterly exposure than many local vineyards, giving the wines a unique structure and remarkable complexity. Under the ownership of the Valton family for the past hundred years, for much of this time, Sainte-Sophie fruit was sold to Charles Heidsieck for premium blends. Today, more and more is being dedicated to single-vineyards wines, especially those of Emmanuel Lassaigne.

Former Charles Heidsieck cellar-master Daniel Thibault confirms the original assessment, saying, “If there is a Montrachet in the Aube, it will be found in Montgueux.”

New Plantings: Reviving Historic Terroir in Coteaux du Morin, Côte de Sézanne, Vitryat, and Montgueux

The story of European wine is distinctly bifurcated: Before phylloxera and afterward. Prior to the Great Blight of the eighteenth century, more than 150,000 acres of Champagne were planted to vine. Today, that number is fewer than 90,000 acres. Root-devouring aphids alone did not account for the decline, of course; a couple of World Wars and the subsequent economic implosion played their role. Whatever the cause, in the process, some historically important terroirs were abandoned.

By the 1960’s, a renaissance had begun to find footing among growers, and Champagne vineland that had lain fallow for half a century was slowly replanted. Nowhere was this more in evidence than in Peter Liem’s Big Four—Coteaux du Morin, Côte de Sézanne, Vitryat and Montgueux, which have re-established themselves as important Champagne growing areas. Although there are fewer grower-producers today than in the past (with more growers selling grapes to major Champagne Houses and cooperatives) this leaves a vast opening for pioneers to learn about the varied faces of these long-untapped soils, climates and exposures.

Champagne Jacques Lassaigne

Wine First

If a poster child was needed for the concept of Champagne’s phoenix rising from the flames of phylloxera, no hill is better suited than Montgueux. And in the endeavor, no white knight may be considered more noble than Jacques Lassaigne. With the original intention of selling grapes to négociant houses, he began to bottle still wine in the 1970’s and Champagne in the ‘80s. His first ‘parcellaire’—a term synonymous with ‘lieu-dit’—was from Le Cotet, a plot that Emmanuel still farms today.

Of it, Emmanuel says, “We have a single area of vines between 55 and 60-years old within this individual vineyard, all Chardonnay, making a wine of intense minerality. It sings with citrus acidity in its youth but as it ages, it fattens. It’s another Champagne which must be treated as a white wine with bubbles, serving it (preferably) not too cold in the correct wine glass.”

Emmanuel Lassaigne, Champagne Jacques Lassaigne

From the outset, the Lassaignes relied on organic agriculture, using no synthetics and allowing the rows to grass over, creating competition with the vines—a technique that reduces yields and produces smaller berries, both indispensable factors in creating great wines. But as a Champagne house, they are decidedly not certified organic, for reasons that betray a small secret among French vignerons worth squirreling away: According to Emmanuel, “The French are masters in the art of paper. Many growers (like us) who work without chemicals prefer to remain uncertified because we resent having to deal with the bureaucracy and pay the fees to be certified in something we’ve been doing for years of our own accord.”

The majority of Lassaigne’s current ten acres is planted to Chardonnay, and lie across the street from his home above the valley that lies between Montgueux and Troyes. As mentioned, he annually purchases an additional six acres of grapes from old vines in top terroirs.

Of Clos Sainte-Sophie he says, “It’s the best vineyard in Montgueux.”

Emmanuel Lassaigne, courtesy of Grand Champagne Helsinki

In the cellar, Lassaigne vinifies all parcels separately and (with the exception of ‘Le Cotet’ and ‘Colline Inspirée’) fermentation is done in stainless steel. The initial fermentations are completed with native yeasts while secondary fermentations rely on a commercial, neutral Aube-originated yeast strain that imparts no aroma to the wine and promotes a very long, cool second fermentation—key to developing the prized mousse of which Champagne is justifiably proud. Although Lassaigne uses sulfur minimally at pressing to prevent oxidation, the domain has been disgorging without sulfur for 32 years. He scoffs at oenologists who insist that sulfur is a preventative measure, saying, “We’ve avoided it for more than a quarter century and to date, nothing has gone wrong.”

Emmanuel also disgorges all the bottles himself, by hand, which is an increasingly uncommon practice in Champagne where machine disgorgement has become the norm.

The human touch plays an integral role in every facet of winemaking with which Emmanuel engages. And it’s fitting, since Champagne is one of humanity’s greatest triumphs.

Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Les Vignes de Montgueux’ Blanc de Blancs Extra Brut ($68)

Champagne Jacques Lassaigne ‘Les Vignes de Montgueux’ Blanc de Blancs Extra Brut ($68)

True to its name, the grapes in ‘Les Vignes de Montgueux’ come from nine individual sites throughout Montgueux where the age of vines is around 35 years and yields are kept to 60 hl/ha (Champagne’s average is 66 hl/ha). Harvest is done at maximum ripeness before the grapes are destemmed and pressed. The base wine undergoes complete malolactic fermentation and is aged in new and old barrels for 12 to 24 months. Once bottled, it is held for one to five years until it is disgorged, corked and released. (Disgorgment Date: March 20, 2022)

The wine shows glints of gold in the glass with lovely dried mango and lemon-lime zest in the aromatics. The palate is vibrantly alive with crisp citrus and creamy melon flavors that are backed by a spine of acidity and dazzling minerality. The finish resonates with succulent pineapple and citrus notes and shows the full, expressive panoply of Chardonnay.

NEW ARRIVAL

A Burgundy By Any Other Name

Domaine Thierry Mortet’s ‘2020 Bourgogne’ $33 (Limited)

(Gevrey-Chambertin, Côte de Nuits)

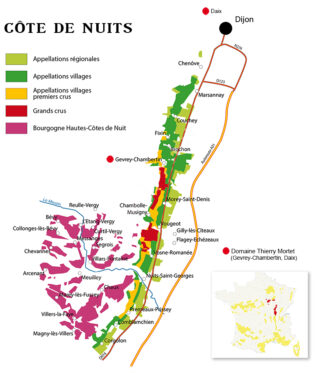

The Côte de Nuits is the northern half of the Côte d’Or. Wines made from Pinot Noir dominate the area’s output, representing 95% of production. Some César is grown to bring backbone and color to Pinot Noir in weak vintages, but the proportion used is always minimal.

Having developed the reputation for quality over quantity, the Côte de Nuits is home to some of the finest red-wine vineyards in the world and includes 24 of Burgundy’s 33 Grand Cru appellations. Their mission statement spills over into the broadest appellation, Bourgogne, and makes these red wines among the best in the world for value. Any estate can declassify any lot from any Burgundian appellation and use this designation, and négociants know this: As a result, that $40 Bourgogne you enjoy may contain juice from vineyards whose names grace labels costing ten times as much.

Domaine Thierry Mortet ‘Cuvée Les Charmes de Daix’, 2020 Bourgogne ($33)

Domaine Thierry Mortet ‘Cuvée Les Charmes de Daix’, 2020 Bourgogne ($33)

‘Love thy neighbor’ is a rule no more golden that at the estate of Thierry Mortet, located at the very center of the village of Gevrey-Chambertin. Officially created in 1992 when Thierry’s father retired and his estate was divided between his two sons. Thierry wound up with ten acres, which he has grown to 21 acres spread over four villages, Gevrey-Chambertin, Chambolle-Musigny, Couchey and Daix, just to the west of Dijon.

Thierry studied enology and viticulture in Beaune and his wife Veronique were joined at the estate by their daughter Lise in 2020. Together they produce around 2,900 cases annually.

‘Les Charmes de Daix’ is produced from 6 different parcels amounting to three acres in total, planted on clay soils with chalky sub-soils. That portion of vines located in the commune of Daix provides delicacy and finesse while those from the commune of Gevrey bring structure and richness. The wine is fresh and fruity, elegant and generous with the aromatic persistence one expects only in much higher-priced Burgundy.

- - -

Posted on 2023.02.02 in France, Champagne

Featured Wines

- Notebook: A’Boudt Town

- Saturday Sips Wines

- Saturday Sips Review Club

- The Champagne Society

- Wine-Aid Packages

Wine Regions

Grape Varieties

Aglianico, Albarino, Albarín Blanco, Albarín Tinto, Albillo, Aleatico, Arbanne, Aubun, Barbarossa, barbera, Beaune, Biancu Gentile, bourboulenc, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Caino, Caladoc, Calvi, Carcajolu-Neru, Carignan, Chablis, Chardonnay, Chasselas, Clairette, Corvina, Cot, Counoise, Erbamat, Ferrol, Fiano, Frappato, Friulano, Fromenteau, Fumin, Garnacha, Gewurztraminer, Godello, Graciano, Grenache, Grolleau, Groppello, Juan Garcia, Lambrusco, Loureira, Macabeo, Macabou, Malvasia, Malvasia Nera, Marsanne, Marselan, Marzemino, Melon de Bourgogne, Merlot, Mondeuse, Montanaccia, Montepulciano, Morescola, Morescono, Moscatell, Muscadelle, Muscat, Natural, Nero d'Avola, Parellada, Patrimonio, Petit Meslier, Petit Verdot, Pineau d'Aunis, Pinot Auxerrois, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, Poulsard, Prieto Picudo, Rondinella, Rousanne, Roussanne, Sangiovese, Sauvignon Blanc, Savignin, Semillon, Souson, Sparkling, Sumoll, Sylvaner, Syrah, Tannat, Tempranillo, Trebbiano, Trebbiano Valtenesi, Treixadura, Trousseau, Ugni Blanc, vaccarèse, Verdicchio, Vermentino, Viognier, Viura, Xarel-loWines & Events by Date

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- February 2004

Search